Abstract

Identified as a major downstream effector of the small GTPase RhoA, Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase (ROCK) is a versatile regulator of multiple cellular processes. Angiogenesis, the process of generating new capillaries from the pre-existing ones, is required for the development of various diseases such as cancer, diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis. Recently, ROCK has attracted attention for its crucial role in angiogenesis, making it a promising target for new therapeutic approaches. In this review, we summarize recent advances in understanding the role of ROCK signaling in regulating the permeability, migration, proliferation and tubulogenesis of endothelial cells (ECs), as well as its functions in non-ECs which constitute the pro-angiogenic microenvironment. The therapeutic potential of ROCK inhibitors in angiogenesis-related diseases is also discussed.

Keywords: Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase (ROCK), angiogenesis, endothelial cell, microenvironment, therapeutic target

Introduction

Angiogenesis is the formation of new capillaries from pre-existing blood vessels. It occurs more frequently in ischemic/hypoxic tissues, with the increased demand of oxygen and nutrients. Physiological angiogenesis is well regulated and plays an indispensable role in embryonic development, wound healing and female menstrual cycle 1-3. Uncontrolled angiogenesis is characterized by the development of immature capillaries in diseases tumors, diabetes, age-related macular degeneration and atherosclerosis 4-7. Thus, inhibiting angiogenesis has become a promising strategy for the treatment of these diseases. In contrast, therapeutic angiogenesis promoting vessels formation helps improve the function of ischemic hearts or limbs caused by occlusion of coronary or peripheral arteries 8, 9. Insights into the underlying mechanisms of angiogenesis may reveal novel targets for angiogenesis-related diseases.

As a well-known effector of small GTPase RhoA, Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase (ROCK) regulates actin reorganization during cell adhesion, migration, contraction and proliferation 10. Angiogenesis is initiated by activation of ECs, followed by EC migration and proliferation, thus it involves the function of ROCK. ROCK is also necessary for constitution of pro-angiogenic microenvironment by regulating gene expression in non-ECs. In this review, we summarized our current understanding of the diverse mechanisms of ROCK in angiogenesis, highlighting the therapeutic potential of ROCK inhibitors.

Molecular structure of ROCK1 and ROCK2

ROCK belongs to the AGC (protein kinase A, G and C, PKA/PKG/PKC) family of serine-threonine kinases 11. There are 2 subtypes of ROCK, ROCK1 (ROCKβ) and ROCK2 (ROCKα). They have a high degree of sequence homology, with 65% amino acid sequences in common and 92% homology within their kinase domains 12. Each ROCK isoform consists of 5 domains, a catalytic kinase domain at the N-terminus, followed by a central coiled-coil domain containing a Rho-binding domain (RBD) and a C-terminal pleckstrin-homology (PH) domain including an internal cysteine-rich domain (Figure 1). Inside cells, ROCK locates primarily in the cytoplasm, but also distributes to the nucleus and membrane 13, 14. ROCK1 and ROCK2 are widely expressed in tissues of embryos and adults 15. While ROCK1 is preferentially expressed in kidney, liver, spleen and testis, ROCK2 is enriched in brain, heart, lung and skeletal muscle 15, 16. Both isoforms are expressed in ECs, in which ROCK1 is mainly distributed in the plasma membrane and ROCK2 is localized in cytoplasm 17.

Figure 1.

Structural domains of ROCK protein. Each ROCK isoform contains 5 domains: a kinase domain, a coiled-coil domain containing a Rho-binding domain (RBD), a pleckstrin-homology (PH) domain containing an internal cysteine-rich domain (CRD). The binding of RhoA-GTP to RBD alters the inhibitory fold structure and frees the kinase domain, leading to the activation of ROCK. In addition, caspase-3-mediated C-terminus cleavage of ROCK1 and granzyme-mediated cleavage of ROCK2 contribute to the activation of ROCK by disrupting the auto-inhibitory intramolecular fold. CRD: cysteine-rich domain; PH: pleckstrin-homology; RBD: Rho-binding domain.

Knockout and transgenic mouse models of ROCK1/ROCK2 genes

The ROCK2 -/- mice were generated in 2003, and 90% of ROCK2 null embryos died due to severe thrombus formation, placental dysfunction and consequent intrauterine growth retardation 18. The few survivors were born runts and subsequently developed without gross abnormality, and were fertile 18. In contrast to ROCK2-/- mice, fetal death did not occur in ROCK1-/- mice. However, most of ROCK1-/- newborns died immediately due to omphalocele, and exhibited eyelids open at birth (EOB) 19. Further studies indicated that both ROCK2-/- and ROCK1+/-ROCK2+/- mice displayed phenotypes similar to that of ROCK1-/- mice due to disrupted assembly of actin bundles in epithelial cells of the eyelids and umbilical rings 20. All the ROCK1-/-ROCK2-/- mouse embryos died in utero between E3.5 and E9.5 21. In addition, ROCK1+/-/ROCK2-/- mice, or ROCK1-/-/ROCK2+/- mice, exhibited embryonic lethality around E9.5 due to impaired vasculature development in the yolk sac 21. Treatment with ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 also destroyed vascular remodeling in wild-type embryos ex vivo 21. These findings provide direct evidence that ROCK is indispensible for developmental angiogenesis. In adults, ROCK2+/- mice exhibited a modest, yet significantly decreased vessel density in the lung 22, while ROCK1+/- mice showed decreased cardiac fibrosis and neointima 23, 24.

In addition to ROCK deletion mouse models, Samuel et al. generated cytokeratin14 (K14)-ROCKII: mERTM mice for inducible expression of ROCK2 25. The expression of the fusion protein ROCK2:mER (ROCK2 with the Rho-binding domain substituted by the modified hormone-binding domain of estrogen receptor) was driven by the promoter of cytokeratin14, a gene specifically expressed in skin keratinocytes. Estrogen analogues, such as 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4HT) and tamoxifen, were then administrated to elicit kinase activity of ROCK 25. Compared with the wild-type mice, transgenic mice with constitutive ROCK activation in skin keratinocytes show an increase of epidermal hyperplasia and a conversion of cutaneous papillomas to invasive carcinomas 26. The healing of full thickness skin wounds is also accelerated in the K14-ROCKII:ER mice 27. To extend the application of the ROCK2:ER system to more tissues, a two-stage system was developed to allow for the conditional activation of ROCK2 in a tissue-selective manner 28. LSL-ROCK2:ER transgenic mice were generated by placing loxP flanked transcription termination cassette (STOP) sequence (LSL) between a cytomegalovirus early enhancer- chicken β-actin (CAG) promoter and the coding sequence for ROCK2:ER. By crossing with tissue- specific CRE recombinase-expressing mouse lines, CRE-mediated recombination between loxP sites removes the STOP sequence to allow the expression of ROCK2:ER fusion protein. Upon stimulation with 4HT, the kinase activity of ROCK2 is triggered, and the activation of ROCK2 was verified in various tissues 28. The 4HT-induced ROCK2 activation in the whole tissues resulted in cerebral hemorrhage and death within 7 days of induction 28. By crossing LSL-ROCK2:ER transgenic mice with genetically modified mice with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, ROCK2 level is specifically elevated in the pancreas, which promotes the growth and invasion of adenocarcinoma 29. To date, conditional ROCK2 activation in vascular ECs has not been reported.

Kinase activity and substrates of ROCK

The activation of ROCK depends on RhoA-GTP, which is transformed from RhoA-GDP by Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (RhoGEF) (Figure 2). In the absence of RhoA-GTP, the C-terminal RBD and PH domains exert an auto-inhibitory effect on the kinase domain by formation of an intramolecular fold 30. The binding of RhoA-GTP to RBD alters the inhibitory fold structure and frees the kinase domain; hence ROCK is activated 30. ROCK is also activated in Rho-independent ways. For instance, caspase-3-mediated C-terminus cleavage of ROCK1 and granzyme-mediated C-terminus cleavage of ROCK2 contribute to the activation of ROCK by disruption of the auto-inhibitory intramolecular fold 31, 32. Furthermore, phospholipids such as arachidonic acid directly activate ROCK in the absence of RhoA-GTP 33, 34.

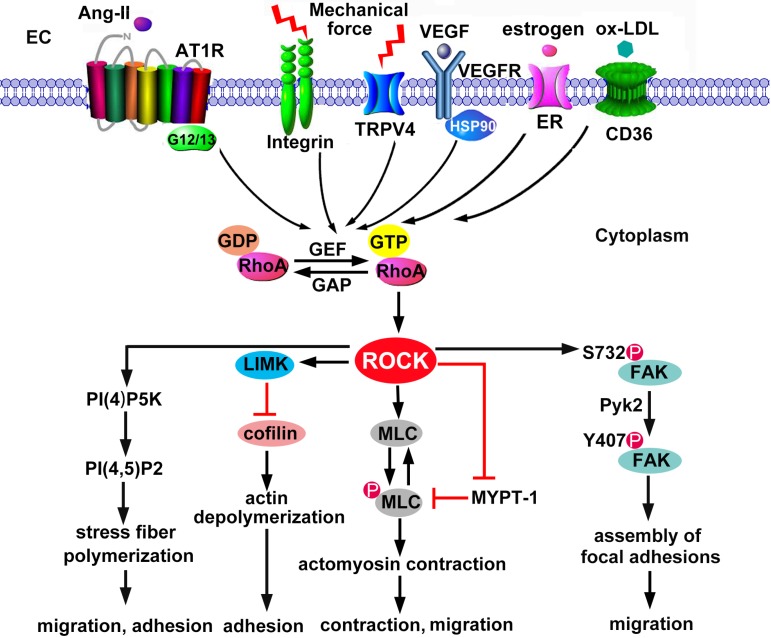

Figure 2.

ROCK activation in endothelial cytoskeleton. ECs are activated by a wide range of stimuli, including chemical molecules and physical mechanical forces. The activated receptors recruit and activate GEFs via adaptor proteins. GEFs stimulate the exchange of GDP for GTP, resulting in RhoA activation. In contrast, GAPs abrogate the GTPase activity of RhoA by accelerating the hydrolysis of bound GTP to GDP. ROCK is an effector of RhoA-GTP. Substrates of ROCK include MLC, MLCP and LIMK. Phosphorylation of MLC and LIMK is involved in actin depolymeriztion and actomysion contraction, thus regulating EC adhesion, contraction and migration. In addition, ROCK phosphorylates PI4P5K. As a main product of PI(4)P5K, PI(4,5)P(2) interacts with actin-associated proteins to stimulate reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and trigger stress fiber polymerization. ROCK also facilitates the phosphorylation of FAK2 by Pyk2, which mediates the assembly of focal adhesions. Ang II: angiotensin II; AT1R: Ang II type 1 receptors; ER: estrogen receptor; FAK: focal adhesion kinase; GEF: guanine nucleotide exchange factor; GAP: GTPase-activating protein; LIMK: LIM motif-containing protein kinase; MLC: myosin light chain; MLCP: MLC phosphatase; TRPV4: transient receptor potential vanilloid 4; Pyk2, proline-rich tyrosine kinase-2; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

The RhoA/ROCK signaling is a major regulator of actin reorganization since various cytoskeletal regulatory proteins are substrates of ROCK (Figure 2). These regulatory proteins include LIM motif-containing protein kinase (LIMK), myosin light chain (MLC) and MLC phosphatase. ROCK-activated LIMK phosphorylates cofilin and inactivates its actin-depolymerization activity, leading to stabilization of actin filaments 35, 36. On the other hand, ROCK promotes the phosphorylation of MLC through phosphorylation and inactivation of MLC phosphatase or direct phosphorylation of MLC, leading to the activation of myosin II and the actomyosin-driven contractility 37. Besides, ezrin/ radixin/moesin 38, adducin 39, 40, and eukaryotic elongation factor 1-α1 (eEF1a1) 41 are downstream targets of ROCK and involved in actin cytoskeleton assembly.

Activation of ROCK in ECs by pro-angiogenic stimuli

The onset of angiogenesis or the 'angiogenic switch' is triggered by the imbalance between pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic molecules 42. Under ischemic or hypoxic microenvironment, pro-angiogenic molecules are mainly produced and secreted from non-ECs. These molecules include vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs), fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), platelet-derived growth factors (PDGFs) and epidermal growth factors (EGFs) 43-46. In addition, inflammatory factors, hormone and lipid act as the pro-angiogenic stimulators 47-50. Mechanical stress caused by cell-ECM or cell-cell interaction changes also promotes angiogenesis 51, 52. In ECs, ROCK mediates both chemical and mechanical pro-angiogenic stimuli-induced cellular functions (Figure 2).

VEGF

VEGF is the most robust angiogenic growth factor 53. In VECs, VEGF binds to two types of receptor tyrosine kinase, VEGF receptor (VEGFR) 1 (also known as fms-like tyrosine kinase-1, Flt-1) and VEGFR2 (also known as fetal liver kinase-1, Flk-1 or kinase insert domain-containing receptor, KDR) 54. VEGFR2 activation contributes to VEGF-stimulated EC migration and proliferation, whereas VEGFR1 negatively regulates these angiogenic effects of VEGF 54. RhoA is quickly activated by VEGF and recruited to the endothelial cytoplasm membrane 55. Studies have shown that the Tyr951 residue of VEGFR2, phospholipase C and the G protein Gq/11 are required for VEGF-stimulated RhoA activation and EC migration 56. The function of RhoA in EC migration is mediated by ROCK, as inhibition of either RhoA or ROCK abolishes VEGF-induced F-actin stress fiber formation and EC migration in vivo and in vitro 22, 54, 55, 57. In addition, the protective effect of VEGF against apoptosis also requires the activation of ROCK 57. In-depth studies explored the specific contributions of each ROCK isoform. In response to VEGF, ECs with knockdown of ROCK2 exhibit a drastic reduction in migration and tube formation, which has not been observed in ECs with ROCK1 knockdown, suggesting that VEGF-induced EC activation is largely mediated through ROCK2 signaling 22.

Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL)

In response to hypoxia and inflammation, angiogenesis is induced within the atherosclerosis plaque 58. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) is a key factor for angiogenesis in atherosclerotic vessels. Both pro-angiogenic (low concentration) and anti-angiogenic (high concentration) effects of ox-LDL have been reported 49, 59. The angiogenic effect of low concentrations of ox-LDL is partially mediated through ROCK signaling. Oh et al. discovered that low concentrations (10-100 μg/ml) of ox-LDL promote angiogenesis of human aortic ECs via receptor CD36-mediated RhoA/ROCK activation 50. Moreover, cholesterol reverses oxLDL-induced endothelial network formation through preventing RhoA/ROCK activation 50. This observation furtherly confirms the significance of ROCK in ox-LDL induced angiogenesis.

Angiotensin II

Angiotensin II (Ang II) type 1 and type 2 receptors (AT1R and AT2R) modulate angiogenesis by opposing effects in the microvascular endothelium 60. VEGF-induced angiogenesis is augmented by Ang II both in vitro and in vivo, exclusively through AT1R via the activation of RhoA/ROCK signaling. In contrast, selective activation of AT2R by its specific agonist or Ang II with AT1R antagonist inhibits VEGF-driven EC migration by repressing RhoA activity 60. As G-protein-coupled receptors, AT1R and AT2R activate two types of G-proteins to regulate RhoA/ROCK signaling. Gα12/13 proteins are activated by AT1R to mediate RhoA activation, whereas Gαi protein activation is required for AT2R-induced RhoA inhibition 60.

Estrogen

Estrogens have been proven to initiate angiogenesis via ROCK activation. Simoncini et al. first reported that estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) interacts with G protein Gα13 to drive actin remodeling and EC migration via the RhoA/Rho kinase/moesin pathway 61. In another study, estradiol enhances the transcription, protein expression, and activity of RhoA in an estrogen receptor-dependent manner 62. Inhibition of ROCK abrogates the expression of cell cycle-related proteins raised by estradiol and hence interrupted EC migration and proliferation 62. 17β-estradiol increases horizontal migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), which is mediated by ROCK2 activation-dependent activation of c-Jun and c-Fos 63. c-Jun and c-Fos translocate into the nucleus and stimulate the transcription of endothelial plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), which is implicated in HUVEC horizontal migration 63. Formononetin, an isoflavone that displays estrogenic properties, binds to ERα and activates ROCK2/matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 2/MMP9 signaling, contributing to EC migration, dramatic actin cytoskeleton spatial modification and angiogenesis 48. Considering the importance of estrogen in the regulation of the menstrual cycle, estrogen-dependent RhoA/ROCK activation may be essential in vascular reconstruction of the endometrium through regulating angiogenesis.

Mechanical forces

In addition to chemical factors, ECs are mainly subject to two types of mechanical force, stretch produced by deformation of blood vessels and shear stress arising from changes in blood flow 64. Under physiological conditions, these mechanical forces maintain the morphology, signal transduction and function of VECs. During pathological process such as vascular obstruction or injury, the changed mechanical forces remodel the conformation of ECM and ECs 65. In response, ECs express mechanosensors such as integrin receptors at cell-cell junctions and cell-matrix adhesions to sense and translate the mechanical forces into electrical or biochemical signals and influence angiogenesis 66, 67. During this process, RhoA/ROCK pathway acts as a transducer of mechanical signals from integrins to cytoskeleton 68. In confluent cultures of bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs), ROCK mediates shear stress-induced cell alignment and stress fiber formation 69. Shear-induced increase in RhoA/ ROCK activity also facilitates EC migration by enhancing the traction force between ECs and the underlying substrate 70. By employing a stretchable three-dimensional (3D) cell culture model, Fischer et al. reported that RhoA/ROCK is required in 3D EC branching guided by local cortical tension 51. By using a similar culture model, Wilkins et al. demonstrated that cyclic uniaxial stretch alone significantly increases endothelial sprouts that aligned perpendicular to the direction of the stretch in a ROCK-dependent way 52. The sprouting number and alignment induced by stretch are suppressed by the ROCK inhibitor Y-27632. Despite of the potent pro-angiogenic activity of VEGF, combination of the stretch and VEGF does not show a synergistic effect on angiogenesis. Moreover, unlike cyclic stretch or VEGF alone, the combination of stretch and VEGF induces angiogenesis through a ROCK-independent mechanism 52. It is likely that receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) rather than ROCK mediates the new sprouts formation induced by the combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF 52.

Studies in tumor capillary ECs further support the importance of RhoA/ROCK in mechanical stress-associated angiogenesis. Unlike normal ECs, tumor capillary ECs exhibit aberrantly high levels of RhoA and ROCK, leading to abnormal mechanosensing and excessive angiogenesis in response to cyclic strain 71. Mechanosensitive ion channel transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) is functionally expressed in ECs, and acts as a mechanosensor of cyclic stretch and flow 72, 73. In normal ECs, TRPV4 senses mechanical force and induces optimal RhoA/ROCK activation necessary for endothelial migration and contraction which is required for partial cell rounding. However, reduction of TRPV4 level in ECs activates Rho/ROCK signaling, resulting in enhanced proliferation, migration, and aberrant tube formation, which could be decreased by the ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 74. Given that TRPV4 is a calcium ion (Ca2+)-permeable nonselective cation channel and TRPV4 activation increases intracellular Ca2+ influx 75, Ca2+ might involve in TRPV4 regulated ROCK activation.

To summarize, ROCK mediates both soluble chemical factors- and physical mechanical force-induced angiogenesis. As these two types of stimulators exist simultaneously in vivo, ROCK may function as an integrator through overlapping or additive effects in ECs. In addition to RhoA, multiple Rho GTPases affect ROCK activities 76. In response to VEGF, the expression of RhoB increases in HUVECs 77. Interference of RhoB mitigates VEGF- induced vessel sprouting and cord formation, partially through activating RhoA-ROCK signaling 77. RhoJ also inhibits RhoA-ROCK signaling in HUVECs 78. Knockdown of RhoJ promotes the activation of RhoA-ROCK signaling and the phosphorylation of MLC, leading to disrupted EC migration and tube formation 78. It is not clear how RhoB and RhoJ suppress RhoA-ROCK signaling, whereas RhoE binds directly to ROCK1 and inhibits RhoA from binding to ROCK1 79. Although RhoE competes with RhoA for binding with ROCK1, the RhoE binding site on ROCK1 protein is different from that of RhoA 79. It appears that angiogenesis is regulated by a dynamic balance of various Rho GTPases, and ROCK might be the convergence point.

ROCK in fundamental stages of angiogenesis

In response to pro-angiogenic stimuli, ECs are shifted from a quiescent state to an active angiogenic state 53. First, EC junctions in the existing vessels dissociate and plasma proteins leak into the extracellular matrix (ECM). The accumulated plasma proteins provide a new ECM for migrating ECs 80. In addition to growth factors, proteases such as MMPs, are secreted by both parenchymal cells and ECs 81. The proteases break down the basement membrane and release the proangiogenic factors that are anchored in ECM 81. These changes facilitate the migration of tip cells under the guidance of a gradient of VEGF or other growth factors. Tip cells are specialized ECs with polarized filopodia, which sense and guide the sprout towards the angiogenic stimulus 82. Following tip cells, the specialized endothelial stalk cells proliferate during sprout extension to form the nascent vascular lumen 83. These sprouts ultimately form capillary-like structures. After vessel fusion and pruning, pericytes and smooth muscle cells are recruited to wrap around and stabilize it. In this section, we dissect the roles of ROCK in the basic stages of angiogenesis, including hyperpermeability, migration, proliferation and tubulogenesis.

Vascular permeability

VEGF, originally known as vascular permeability factor (VPF) 84, is the main contributor of vascular hyperpermeability through activating ROCK. ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 blocks VEGF-induced microvascular hyperpermeability in a dose-dependent manner 85. Pretreatment with exoenzyme C3, an inhibitor of RhoA, significantly represses the albumin trans-endothelial flux 86. In addition, ROCK increases endothelial permeability mainly through promoting the cellular contraction via MLC phosphorylation and contractile fibers formation. The ROCK regulates cell junctions. ROCK promotes the dissociation of cell-cell adherens junctions (AJs) by suppressing VE-cadherin expression and its membrane localization 87, 88. In addition to VE-cadherin, ROCK inhibits expression of occludin and claudin-1, the major components of tight junctions, leading to lipopolysaccharide-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction 89.

Several mechanisms are found to constrain ROCK activity and its ability of increasing vascular permeability under physiological conditions. Generally, Krev interaction trapped protein 1 (KRIT1)/cerebral cavernous malformations 2 protein (CCM2) complex maintains the endothelial barrier function by suppressing RhoA/ROCK signaling 90. However, the interaction between KRIT1 and CCM2 is disrupted in endothelium of human cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs), resulting in hyperactivation of ROCK and serious vascular leakage, which could be ameliorated by the ROCK inhibitor fasudil (also known as HA1077) 90. In addition to KRIT1, MEKK3 (MAPK/ERK kinase kinase 3) forms a protein complex with CCM2 to maintain vascular integrity in embryonic organs and neonatal brains 91. Both CCM2 and MEKK3 exert an inhibitory effect on ROCK. Y-27632 partially rescues the disrupted neurovascular integrity caused by MEKK3 deficiency, indicating that MEKK3/ CCM2-mediated repression of the Rho/ROCK pathway is required for maintenance of vascular integrity 91.

Migration

EC migration requires the contraction of actomyosin, the rearrangement of stress fibers and the formation of focal adhesions 92, all of which are regulated by ROCK. First, ROCK activation enhances actomyosin contraction in ECs through promoting the phosphorylated of MLC. Besides, ROCK phosphorylates LIMK, which phosphorylates and inactivates its downstream substrate, cofilin, leading to inhibition of actin depolymerization and stress fiber rearrangement in VEGF-stimulated ECs 35. Cell migration requires dynamic assembly and disassembly of focal adhesions 93. FAK phosphorylated at Tyr407 forms a complex with paxillin and vinculin to promote the formation of focal adhesion 94. Le Boeuf et al. found that VEGF-induced VEGFR2-HSP90 interaction activates RhoA/ROCK signaling, which in turn promotes the phosphorylation of FAK on Tyr407 94. Although ROCK does not directly phosphorylate Tyr407, it phosphorylates Ser732 of FAK and modifies the conformation of FAK, leading to the phosphorylation of FAK on Tyr407 by proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2) 95.

In addition, Rho/ROCK-dependent generation of PI(4,5)P2 by phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase (PI(4)P5K) induces activation of phospholipase C and elevation of intracellular calcium ion, facilitating Semaphorin 4D-induced cytoskeletal polymerization in HUVECs 96. As a scaffold for RhoA/ROCK, α-catulin localizes on vimentin intermediate filaments and increases migration of pulmonary vascular ECs in a ROCK-dependent manner 97. Recent studies showed that ECs migrate as a group joined via cadherin-containing AJs in sprouting angiogenesis 98. The association of ROCK2 with Raf is required for the recruitment of ROCK2 to AJs, which promotes the maturation of AJs by activation of junctional myosin. Disruption of the Raf/ROCK complex impairs the maturation of AJs, leading to angiogenesis defects 98.

Proliferation

The effects of ROCK on EC proliferation is attributed to its role on cytoskeleton. For instance, reduction of FAK promotes RhoA/ROCK activities, which in turn, augments cytoskeletal tension, creating a pro-proliferative condition 99. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) has been reported to promote angiogenesis 47. However, studies also showed that TNF-α suppresses EC proliferation in a ROCK-dependent way. TNF-α exposure leads to ROCK-mediated phosphorylation of cytoskeletal protein ezrin, which translocates to the nucleus and represses the transcription of cyclin A, therefore, inhibiting proliferation 100.

In addition, ROCK regulates EC proliferation by its targeted gene expression associated with cell cycle. In the hypoxic condition, ROCK2 promotes proliferation of pulmonary arterial ECs though upregulating the expression of cyclin A and cyclin D1 101. Rho/ROCK signaling mediates oxLDL-induced EC proliferation through downregulation of cell cycle inhibitor p27 102. Integrin cytoplasmic domain-associated protein-1 (ICAP1) inhibits ROCK, and increases p21/p27, resulting in suppression of EC proliferation 103.

Tubulogenesis

Lumen formation or tubulogenesis is an essential process in angiogenesis 104. Initially, clearance of cell-cell junctions between ECs to the lateral borders is required for the proper formation of a lumen. The apical junctions is controlled by F-actin and non-muscle myosin II (NMII) contractility mediated by the signaling of Ras interacting protein 1 (Rasip1) 105. Rasip1 promotes the activity of Cdc42, which in turn stimulates Pak4 to activate NMII. The latter controls remodeling of pre-apical junctions, allowing the lumen to open. In addition to apical junction clearance, Rasip1 binds to its GTPase activating protein, Arhgap29, which subsequently inhibits activity of RhoA 105, 106. Signaling of RhoA/ROCK contributes to tubulogenesis through regulation of vessel diameter by suppressing lumen expansion via activity of NMII. A loss of RhoA/ ROCK signaling results in an overexpansion of the lumen, thus compromising the structural integrity of the vessel. Therefore, these two signaling pathways (Rasip1/ Cdc49/ Pak4) and (Rasip1/ Arhgap29/ RhoA/ ROCK) converge on NMII to regulate apical junction remodeling and lumen expansion respectively that are essential for tubulogenesis.

Together, ROCK promotes endothelial proliferation, permeability, migration and tubulegenesis. In addition, ROCK was reported to drive proliferation by spatiotemporally governing cytokinesis 107-109 and by increasing centrosome amplification in epithelial cells 110, 111. ROCK also promotes the progression of G1 to S phase of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) through manipulating cyclin expression 112, 113. RhoA/ROCK activation shortens the half-life of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) mRNA and hence inhibits the expression of eNOS in ECs 114. In contrast, overexpression of eNOS suppresses Ang II-induced migration of VSMCs by inhibition of G12/13-RhoA- ROCK signaling, suggesting ROCK as an eNOS downstream target 115. These mechanisms need to be furtherly studied in ECs.

Crosstalk between RhoA/ROCK signaling and other signaling pathways in ECs

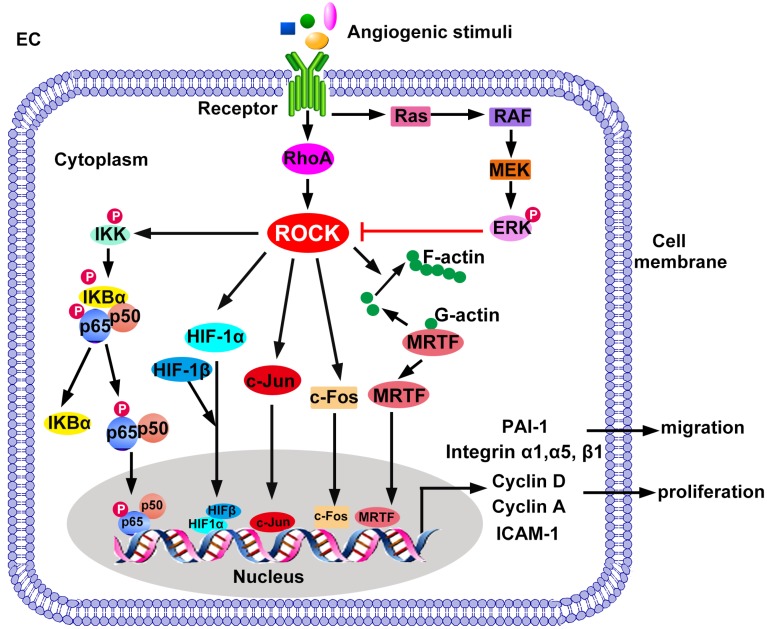

NF-κB

In ECs, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling regulates transcription of genes to favor angiogenesis. Inhibition of NF-κB blocks capillary tube formation by suppression of pro-angiogenic factors such as IL-8, MMPs, intercellular cell adhesion molecule (ICAM) and VEGFR2 116-119. Both ROCK and NF-κB are activated by lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), a well-known inflammation mediator. NF-κB functions downstream of ROCK to mediate LPA-induced expression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) 120. Although LPA-induced IL-8 expression is ROCK dependent, it is independent of NF-κB signaling 120.

NF-κB is a key regulator of thrombin- and TNF-α-induced ICAM-1 gene transcription in ECs 121. In thrombin-induced ICAM-1 expression, RhoA/ROCK pathway increases phosphorylation of IκB kinase (IKK), leading to IκBα degradation, RelA/p65 subunit phosphorylation and translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus 121. Distinct from thrombin, TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation and ICAM-1 gene transcription in ECs are RhoA/ROCK independent, despite of the fact that TNF-α activates RhoA/ROCK in ECs 121. Furthermore, a regulatory pattern occurs in mesangial cells, in which TNF-α promotes nuclear uptake of RelA/p65 by the aid of ROCK-mediated cytoskeletal organization, which is independent of IκBα degradation or p65/RelA phosphorylation 122. Whether such mechanism exists in ECs needs to be elucidated.

MRTF-A

Myocardin-related transcription factor (MRTF) serves as an actin-regulated transcription coactivator for the serum response factor (SRF) 123. MRTF-SRF signaling elevates transcription of VE-cadherin (CDH5) 124 and cysteinerich 61 (CYR61, also called CCN1) 125, thereby regulates vascular integrity, vessel growth and maturation. During sprouting, SRF/MRTF specifically enhances development of filopodia protrusion in tip cells by activating Myl9 gene expression, which encodes myosin regulatory light polypeptide 9 126.

The activation of MRTF-SRF is mediated by ROCK 127. Briefly, the interaction between globular actin (G-actin) and MRTF retains MRTF within the cytoplasm of resting cells 123. Upon activation, Rho GTPase and ROCK induce G-actin to polymerize into filamentous actin (F-actin) via ROCK-LIMK-cofilin pathway, dissociating MRTF from G-actin to enter the nucleus 127. In the nucleus, MRTF interacts with the transcription factor SRF to induce target gene transcription 127. In addition, ROCK promotes phosphorylation of MRTF-A, which facilitates the expression of SRF-responsive genes 128.

Upon activation by VEGF, Rho/ROCK signaling promotes nuclear translocation of MRTF-A in mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which differentiate into ECs 129. RhoA/ROCK/MRTF-A signaling also regulates differentiated multipotent MSCs by increasing expression of integrins. Treatment with either Rho inhibitor C3 transferase or ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 markedly reduces expression of integrin α1, α5 and β1, and completely abrogates sprouting of MSC-derived ECs 130.

Hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1)

Advanced solid tumors and ischemic tissues are featured by hypoxic microenvironment 131. Hypoxia activates transcriptional factor HIF which promotes transcription of pro-angiogenic genes 131. In normoxic condition, HIF-1α is ubiquitinated and degraded rapidly 132. However, HIF-1α is stabilized in hypoxic condition 133. Takata et al. reported that low oxygen conditions stimulate RhoA activity in HUVECs. Interfering with RhoA or ROCK2 by small interfering RNAs, as well as fasudil pretreatment, promote degradation of HIF-1α by proteasome. Therefore, HIF-1α-dependent expression of VEGF is disrupted 133. In this study, although protein levels of HIF-1α and VEGFR2 are inhibited by fasudil in ECs, their mRNA levels remain unchanged, suggesting that RhoA/ROCK pathway involves in posttranscriptional regulation of HIF-1α/VEGFR2 expression. These results emphasize the role of Rho/ROCK in regulating protein degradation or translation. Further studies are needed to determine the mechanism by which Rho/ROCK pathway modulates HIF-1α ubiquitination.

ERK

The negative regulation between ERK and ROCK signaling has been reported in ECs. ERK signaling antagonizes ROCK during angiogenesis 134. Src family kinases (SFK) activates ERK, which in turn restrains the RhoA/ROCK pathway, leading to the mitigation of endothelial tube regression 134. Inhibition of ERK signaling reduces tube formation of ECs and suppresses angiogenesis through activating ROCK- MLC pathway, which is abrogated by ROCK inhibition 135. On the other hand, ROCK acts as a negative regulator of ERK signaling pathway since ROCK inhibitor H-1152P enhances VEGF-induced ERK1/2 activation in ECs 136. Crosstalk of RhoA/ ROCK signaling in ECs has been summarized in Figure 3.

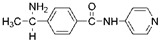

Figure 3.

ROCK-regulated gene expression in EC migration and proliferation. ROCK promotes translocation of p65/p50, c-Jun, c-Fos, and HIF-1α/HIF-1β into the cell nucleus. ROCK also releases MRTF from inhibitory G-actin in the cytoplasm and promotes nuclear translocation of MRTF. ERK negatively regulates ROCK signaling. The transcription factors bind to specific DNA elements to activate transcription of target genes essential for EC migration and proliferation. ERK: extracellular regulated protein kinase; HIF: hypoxia-inducible factor; ICAM-1: intercellular adhesion molecule-1; IκB: inhibitor of NF-κB; IKK: IκB kinase; MEK: mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; MRTF: myocardin-related transcription factor; PAI-1: plasminogen activator inhibitor-1.

ROCK in regulation of the angiogenic microenvironment

The communications between ECs and the surrounding microenvironment are necessary for ECs activation and angiogenesis 4. The angiogenic microenvironment is constituted by extracellular matrix, various secretary molecules, and adjacent non-ECs including parenchymal cells, perivascular mural cells, and inflammatory cells 4. In this section, we discuss the roles of ROCK in regulating expression of VEGF and MMPs, release of microvesicles, and behavior of macrophages and pericytes (Figure 4 and Table 3).

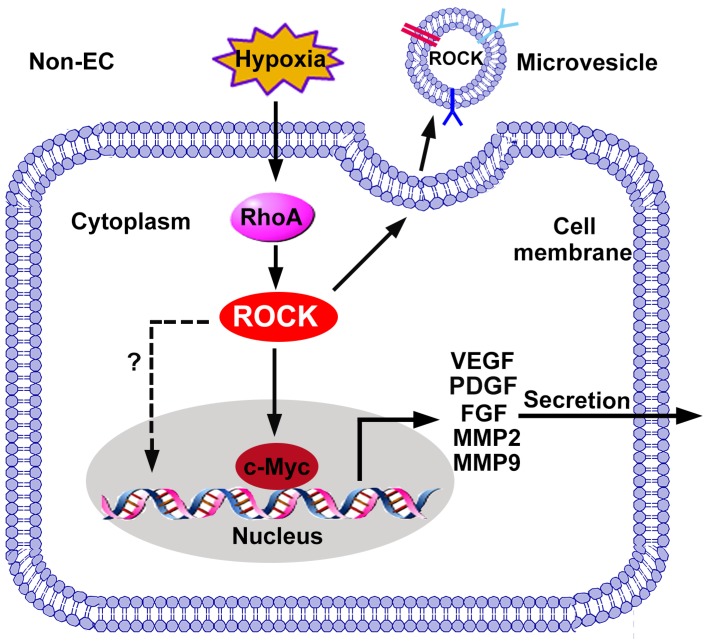

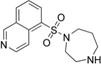

Figure 4.

ROCK regulated gene expression in non-ECs. The expression of pro-angiogenic factors in non-ECs is regulated by the RhoA/ROCK pathway. ROCK promotes c-Myc binding to VEGF promoter and increases the transcription of VEGF. In addition, ROCK increases expression of FGF, MMP2/9 and TGF-β through unknown mechanisms. ROCK is also required for the release of microvesicles, and ROCK can be encapsulated into microvesicles to be received by ECs. FGF: fibroblast growth factor; PDGF: platelet-derived growth factor; MMP: matrix metalloproteinase; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

Table 3.

Summary of genes and proteins regulated by ROCK in angiogenesis

| Gene or protein | Expression | Mechanism | Function of ROCK in angiogenesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF | ↑ | Rho/ROCK/c-Myc promotes transcription of VEGF gene. | Promotes EC migration, proliferation, increases cell permeability 137, 138 |

| MMP | ↑ | Unknown. | Cleavage of ECM 142-144 |

| Integrins α1, α5 and β1 | ↑ | RhoA/ROCK/MRTF-A increases transcription of genes encoding integrins α1, α5 and β1. | Promotes migration and tube formation 130 |

| HIF | ↑ | ROCK inhibits proteasome-mediated degradation of HIF-1α. | Regulates transcription of genes involved in angiogenesis 133 |

| VEGFR2 | ↑ | Rho/ROCK regulates VEGFR-2 protein level posttranscriptionally. | Promotes ECs migration, proliferation, increases cell permeability 133 |

| IL-8 | ↑ | ROCK increases transcription of IL-8 gene through p38 and JNK signaling. | Increases inflammatory responses 120 |

| MCP-1 | ↑ | RhoA/ROCK increases transcription of MCP-1 gene through p38/JNK/NF-κB signaling. | Increases inflammatory responses 120 |

VEGF

ROCK is an upstream kinase regulating the expression of VEGF from non-ECs. In colon cancer cells, hypoxia activates RhoA-ROCK signaling, which activates VEGF gene transcription by increasing the binding affinity of c-Myc and the VEGF promoter 137. The Rho-ROCK-c-Myc cascade also contributes to VEGF induction in ovarian cancer cells 138. Moreover, administration of ROCK inhibitor AMA0428 decreases VEGF levels in the diabetic retina, suggesting the function of ROCK in promoting VEGF expression 139.

MMPs

During angiogenic sprouting, MMPs are required for ECM degradation 140. Besides, MMPs facilitate release of ECM-bound angiogenic growth factors, cleave the adhesions junctions, proteolyze ECM components to expose the binding site with integrin, all of which promote angiogenesis 141. Studies demonstrate that ROCK increases the expression and secretion of MMPs from non-ECs. For instance, RhoA knockdown reduces the activities of RhoA and ROCK, and suppresses expression of MMP2 and MMP9 in breast cancer cells 142. ROCK inhibitor fasudil suppresses gene and protein expressions of MMP2 and MMP9 in glioma cells 143. Inhibition of Rho or ROCK blocks PDGF-BB-induced MMP2 expression in rat VSMCs 144.

Extracellular vesicles

Extracellular vesicles are classified as exosomes, microvesicles and apoptotic vesicles 145. Their cargo varies with respect to proteins, lipids and nucleic acids, depending on the cells which they originate from 146. After entering recipient cells, they facilitate cell-to-cell communication in diseases including pathological angiogenesis 146. Yi et al. found that exosomes derived from metastatic ovarian cancer enhance viability, migration and tube formation of HUVECs. Mass spectrometry analysis revealed higher levels of 10 pro-angiogenic proteins, including ROCK1 and ROCK2, in exosomes secreted from high-grade ovarian cancers compared to low-grade ones 147. In another study, microvesicles generated from rat plasma during cerebral ischemia encapsulate active ROCK and increase permeability of the endothelial barrier in vitro 148. Pre-treatment of either endothelial barriers or microvesicles themselves with Y-27632 before the co-culture attenuates the reduction of transendothelial electrical resistance 148. It is noteworthy that ROCK is also involved in the generation of microvesicles, which requires cytoskeleton reorganization and actin-myosin contraction 149.

Macrophages

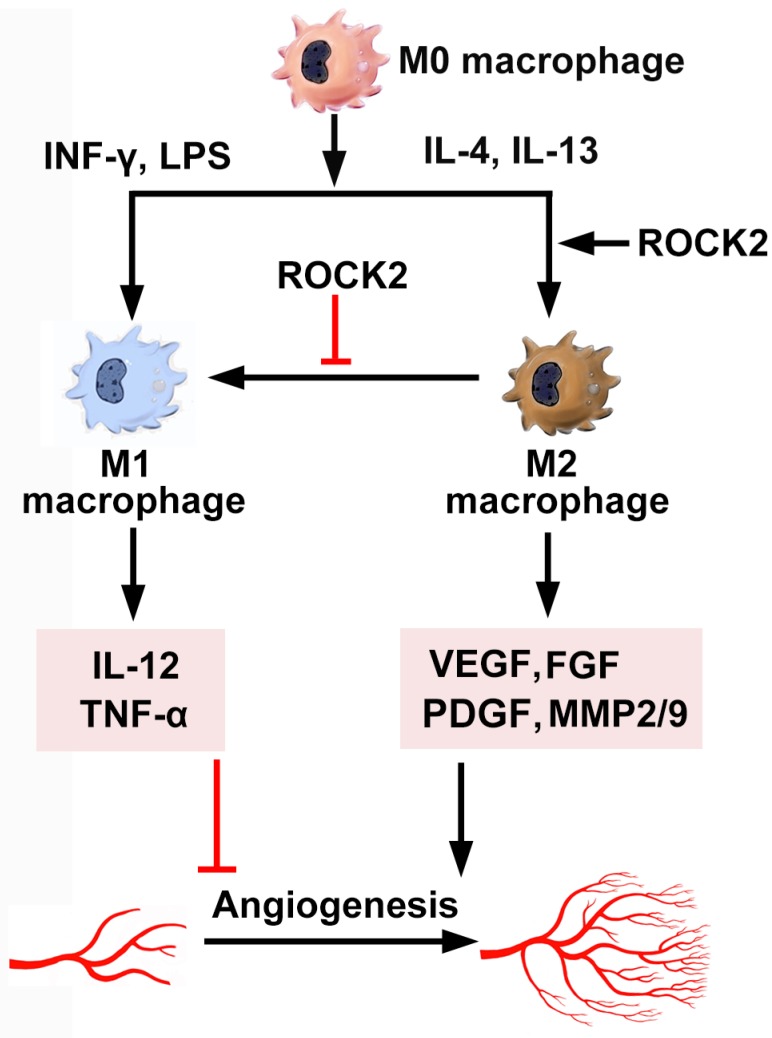

Macrophages synthesize adhesion molecules, and release chemokines, growth factors, and proteases, amplifying angiogenesis in inflammatory diseases 150. Two types of active macrophages exist in vivo. Monocyte-derived non-polarized macrophages (M0) are polarized to M1 and M2 phenotypes under the stimulation of LPS/IFN-γ and IL-4/IL-13, respectively 151. ROCK regulates polarization and inflammatory cytokine secretion of macrophages (Figure 5). First, ROCK determines whether macrophages polarize into M1 or M2 subtypes. ROCK2 activation preferentially promotes the polarization and function of M2 macrophages 152. Injection of M2 macrophages enhance choroidal neovascularization, while M1 macrophages reduce it 152, possibly by secretion of IL-12 and TNF-α. Selective ROCK2 inhibition decreases M2-like macrophages and choroidal neovascularization in aged mice with macular degeneration 152. Similarly, M1 macrophages have anti-angiogenic effects, whereas M2 macrophages promote angiogenesis through secretion of VEGF, FGF, PDGF, and MMPs 153, 154. RhoA/ROCK signaling has been demonstrated to regulate macrophage phenotype, polarity and function, probably through regulating the actin cytoskeleton 155. Disruption of RhoA/ROCK pathway induces extreme elongation of M0 and M2 but not M1 macrophages and inhibits expression of M2-specific but not M1-specific molecular markers 155. Therefore, targeting M2 macrophages by specific ROCK2 inhibitors is promising for anti-tumor therapy.

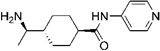

Figure 5.

ROCK activation in macrophages. Monocyte-derived non-polarized macrophages (M0) are polarized to M1 and M2 phenotypes under the stimulation of LPS/IFN-γ and IL-4/IL-13, respectively. ROCK2 promotes the polarization of M2 macrophages. Inhibition of ROCK2 modifies the morphological properties of M2 macrophages, thereby inhibits the expression of VEGF, PDGF, FGF and MMPs. The cytokines, proteases and growth factors released by M2 mediate its pro-angiogenic role. Moreover, inhibition of ROCK2 repolarizes M2 to M1, which may repress angiogenesis by secretion of IL-12 and TNF-α. FGF: fibroblast growth factor; IL: interleukin; INF-γ: interferon-γ; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; PDGF: platelet-derived growth factor; MMP: matrix metalloproteinase; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

Pericytes

Pericytes are required for vascular stability and maturation 156. They are incorporated into the newly formed vessels to support angiogenesis as a constituent of the vessel wall 156. Durham et al. reported that deletion of ROCK-associated myosin phosphatase-RhoA-interacting protein (MRIP) in pericytes enhances contractility and force production, which in turn increases angiogenic sprouting of the co-cultured ECs 157. In addition, ROCK facilitates the communications between ECs and pericytes. In high glucose-treated ECs, activation of ROCK promotes the shedding of endothelial microvesicles carrying miR-503 158. Taken up by recipient pericytes, these microvesicles reduce expression of Ephrin-B2 (EFNB2) and VEGF, resulting in impaired migration and proliferation of pericytes 158.

Therapeutic potential of ROCK inhibitors

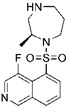

Considering the vital role of ROCK in angiogenesis, targeting ROCK may have therapeutic potential for angiogenesis-related diseases. To date, various ROCK inhibitors have been produced. Among these inhibitors, fasudil and ripasudil have been approved clinically for cerebral vasospasm and glaucoma, respectively 159. The crystal structures of ROCK1 complexes with 4 different ATP-competitive inhibitors, including fasudil (Protein Data Bank code: 2ESM; Figure 6, generated by PyMOL, Schrödinger, Inc.), hydroxyfasudil, Y-27632 and H-1152P, have been revealed 160, 161. Proposed by Takami et al., the ATP-binding pocket can be divided into 3 regions according to the crystal structures 162. As shown in Figure 6C, the isoquinoline ring of fasudil is structurally similar to purine, therefore it binds to the ATP adenine-binding region (A region) at the bottom of the pocket in the kinase domain of ROCK. The sulfonyl group of fasudil serves as a linker and occupies the ATP pentose ring-binding region of the pocket (F region). The linker connects the isoquinoline ring and the piperazine ring of fasudil which locates in the opening area at the top of the pocket (D region).

Figure 6.

Crystal structure of ROCK bound with fasudil. (A) Ribbon representation of overall crystal structure of ROCK (blue) in complex with fasudil (red); (B) Amino acid residues in the ROCK kinase domain interact with fasudil; (C) Cavity surface representation of ATP-binding pocket in the ROCK kinase domain. It is composed of A, F, and D regions. The isoquinoline ring of fasudil occupies A region. The piperazine ring occupies D region. The sulfonyl group that links the isoquinoline ring and the piperazine ring binds to F region. Protein Data Bank code: 2ESM. Images were generated using PyMOL (Schrödinger, Inc.).

The development of high-selective inhibitors for ROCK is restricted due to the high homology of ATP-binding region between ROCK and several other protein kinases. Therefore, most of the ROCK inhibitors are not completely specific, and may target other kinases 163-167. As shown in Table 4, the IC50 values of fasudil (1.65 μM), Y-27632 (3.27 μM) and H-1152P (0.36 μM) against cGMP dependent protein kinase (PKG, also known as protein kinase G) are just 10 to 30 times higher than those against ROCK2 (0.158, 0.162 and 0.012 μM, respectively) 168. Within the concentration ranges, these inhibitors repress ROCK and PKG. Both angiogenic and anti-angiogenic functions of PKG have been reported 169, 170. Modulation of PKG might contribute to the effects of fasudil, Y-27632 and H-1152P on angiogenesis. Besides PKG, ROCK inhibitors target kinases such as PKA, PKC and CaMKII (Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II) with relatively low IC50 values. This may partially explain the distinct effects of ROCK inhibitors on angiogenesis. Studies using Y-27632 or fasudil as ROCK inhibitors demonstrated conflicting results 135, 136, 171. The anti-angiogenic function of Y-27632 or fasudil is likely mediated by other kinases together with ROCK under these experimental settings. Therefore, the off-target effects of ROCK inhibitors should be considered when evaluating the role of ROCK on angiogenesis.

Table 4.

Effects of ROCK inhibitors on angiogenesis

| TherapeuticImplications | Compound | IC50 values for ROCK (μM) | IC50 values for off-target protein kinases (μM) | Models | Pharmacological effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retinal angiogenesis |

Ripasudil (K-115) |

ROCK1 (0.051), ROCK2 (0.019) 166 | PKA (2.1), PKC (27), CaMKII (0.37) 166 | oxygen-induced retinopathy | Reduces retinal hypoxia area, normalizes retinal neovasculature 178 |

| AMA0526 (structure undisclosed) |

Undisclosed. | Undisclosed. | corneal micropocket assay | Inhibits corneal neovascularization, decreases inflammatory cell infiltration 179 | |

| AMA0428 (structure undisclosed) |

Undisclosed. | Undisclosed. | neovascular age-related macular degeneration | Reduces choroidal neovascularization, blocks inflammation and fibrosis 180 | |

H-1152P |

ROCK2 (0.012) 168 |

PKA (3.03), PKC (5.68), PKG (0.36), MLCK (28.3), CaMKII (0.18), GSK3α (60.7), Src (3.06), MKK4 (16.9), EGFR (50) 168 | oxygen-induced retinopathy | Enhances sprouting angiogenesis driven by VEGF 136 | |

|

Tumor angiogenesis |

Wf-536 |

ROCK kinase domain (0.4) 167 | PKN kinase domain (0.4) 167 | a lung cancer cell-transplanted mouse model | Inhibits invasion and migration of cancer cells, inhibits formation of capillary-like tubes 184 |

| Wf-536 and Marimastat (an MMP inhibitor) |

Not available. | Not available. | human prostate cancer xenotransplants | Suppresses angiogenesis and growth of tumor, improves survival 185 | |

fasudil (HA1077) |

ROCK2 (0.158) 168 | PKA (4.58), PKC (12.3), PKG (1.65), MLCK (21.6), CaMKII (6.7), GSK3α (>100) 168 | an intracerebral human glioma cell xeno-graft mouse model | Suppresses angiogenesis and tumor growth 143 | |

Y-27632 Y-27632 |

ROCK2 (0.162) 168 |

PKA (>100), PKC (25.8), PKG (3.27), MLCK (>100), CaMKII (13), GSK3α (50) 168 | tumor capillary ECs isolated from transgenic TRAMP mice bearing prostate adenocarcinoma | Normalizes the ability of tumor ECs to form tubular networks, restores mechanosensitivity 71 |

CaMKII: Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II; GSK3α: glycogen synthase kinase 3 alpha; MKK4: mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4; MLCK: myosin light-chain kinase; PKA: protein kinase A; PKC: protein kinase C; PKG: cGMP dependent protein kinase; PKN: protein kinase N; TRAMP: transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate.

The ATP-binding regions of ROCK1 and ROCK2 are almost identical, making it difficult to develop ROCK isoform-selective inhibitors 172. Recently, several ROCK2 specific inhibitors have been discovered by means of various screening methods 172. These inhibitors have a high selectivity for ROCK2, thus will help investigate the role of each ROCK isoform in diseases.

Emerging drug delivery carriers, including extracellular vesicles, might be used to deliver ROCK inhibitors to enhance the specificity and therapeutic efficacy. Studies have shown that ROCK inhibitor fasudil can be efficiently loaded into liposomes 173, 174. Recently, Gupta et al. developed erythrocytes derived nanoerythrosomes as stable and efficient delivery carriers for slow and continous release of fasudil 175. The half-life of fasudil in vivo is extended in nanoerythrosomes 175, and targeting specificity is improved through conjugating a peptide specially located in pulmonary arterial hypertension lesions with the nanoerythrosomes 176. This carrier system exerts a significant pulmonary vasodilatory effect by ROCK inhibition, and has minimal effect on systemic arterial pressure 176.

To date, ROCK inhibitors have been examined in animal models of ocular angiogenesis and tumor angiogenesis (Table 4).

Ocular angiogenesis

Angiogenesis within the eyes contributes to vision loss in several ocular diseases, including age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy 177. ROCK inhibitor ripasudil (also known as K-115) significantly suppresses migration and proliferation of retinal microvascular endothelial cells (HRMECs) by reduction of VEGF-induced ROCK activation 178. In mice with oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR), eye drops with 0.8% ripasudil effectively reduce the area of retinal hypoxia induced by OIR. Moreover, ripasudil normalizes vascularity and increases retinal vascular perfusion 178. In the corneal micropocket assay, another model of angiogenesis in the mouse eye, ROCK inhibitor AMA0526 efficiently inhibits corneal neovascularization and decreased inflammatory cell infiltration 179. In addition, ROCK inhibitor AMA0428 decreases vessel growth and leakage in a mouse model of laser-induced choroidal neovascularization 180.

Tumor angiogenesis

Constitutive activation of ROCK is often associated with invasive and metastatic phenotypes of human cancers 181-183. Tumor-derived ECs display an enhanced ability to form capillary networks, correlating with a constitutively high level of RhoA/ROCK signaling 71. In a lung cancer cell-transplanted mouse model, Wf-536 (also known as Y-32885), a derivative of Y-27632, inhibits cancer cell invasion and EC migration 184. Wf-536 and the MMP inhibitor marimastat display a synergistic anti-angiogenic effect in a prostate cancer xenotransplant model 185. Moreover, ROCK inhibitors normalize function and structure of tumor vasculature 71, which is highly permeable due to lack of uniform pericyte and basement membrane coverage 186, 187.

Conclusions and Perspectives

ROCK conditions tissue microenvironment by promoting the secretion of growth factors and cytokines from non-ECs. These pro-angiogenic factors along with mechanical forces resulting from EC-microenvironment interaction, in turn, modulate ROCK signaling to regulate EC function in angiogenesis, including permeability, migration, proliferation and tubulogenesis. ROCK contributes to these cellular functions largely through regulation of cytoskeleton-associated proteins. In addition, several transcription factors are activated by ROCK to regulate expression of pro-angiogenic genes.

With ongoing efforts to decipher its role in angiogenesis, it may become possible to target ROCK for anti-angiogenic treatment of cancer, ocular neovascularization and other angiogenesis-related diseases. ROCK inhibitors showed significant prospects for chemotherapy based on their anti-angiogenic effects and their ability to normalize tumor vessels. It may be more effective to combine ROCK inhibitors with other angiogenesis antagonists, including MMP inhibitors or VEGF antibodies, to enhance the anti-angiogenic effects.

Although extensive studies on ROCK have been performed, many issues remain unresolved, such as the off-target effect of ROCK inhibitors and the isoform-specific regulation of angiogenesis. There is also an unmet need to develop more specific and clinically suitable ROCK inhibitors to improve anti-angiogenic therapies.

Table 1.

Summary of phenotypes of ROCK knockout mice

| Genotype | Genetic background | Phenotype | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROCK1-/- | C57BL/6 | Eyelid open at birth (EOB), omphalocele, neonatal death (>90%); survivors subsequently develop normally, fertile and apparently healthy 19. | Disorganized actin bundles in the epithelial cells of eyelid and umbilical ring 19. |

| ROCK2-/- | C57BL/6 | EOB, omphalocele, fetal death (~90%) 20; thrombus formation in the labyrinth layer, placental dysfunction, intrauterine growth retardation; survivors are born runts and subsequently develop without gross abnormality, and are fertile 18. | Disorganized actin bundles 20; dysfunction of embryo-placenta interaction 18. |

| ROCK1-/-ROCK2-/- | C57BL/6 | All embryos die in utero between 3.5 and 9.5 days postcoitum (dpc) 21. | Seriously impaired mouse development 21. |

| ROCK1+/- | C57BL/6 | Viable and fertile without obvious phenotypic abnormalities 18; decreased cardiac fibrosis 23; reduced neointima formation after vascular injury 24. | Decreased expression of CTGF 23; decreased ICAM and VCAM expression and leukocyte recruitment 24. |

| ROCK2+/- | C57BL/6 | Viable and fertile without obvious phenotypic abnormalities 18; decrease of blood vessel density in the lung compared with ROCK1+/- mice 22. | Blood vessel formation in the lung is largely dependent on ROCK2 signaling 22. |

| ROCK1+/-ROCK2+/- | C57BL/6 | EOB and omphalocele 20. | Disorganized actin bundles 20. |

|

ROCK1+/-ROCK2-/- or ROCK1-/-ROCK2+/- |

C57BL/6 | Embryos die during a period from 9.5 to 12.5 dpc with defective vasculogenesis and impaired body turning in the yolk sac 21. | Impaired actomyosin contractility appears to contribute to endothelial dysfunctions during vasculogenesis 21. |

Table 2.

Summary of the phenotypes of ROCK transgenic mouse.

| Genotype |

Genetic background | Activator of mouse ROCK activity | Tissues with conditional ROCK activation | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K14-ROCKII-mERTM 25 | FVB/N | 4HT | Keratinocytes in the skin | Induces epidermal hyperplasia and the conversion of cutaneous papillomas to invasive carcinomas 26; accelerates the healing of full thickness skin wounds 27. |

| K14-CRE; LSL-ROCK2-ER | C57BL/6 | tamoxifen | Keratinocytes in the skin | Not mentioned 28. |

| MMTV-CRE; LSL-ROCK2-ER | C57BL/6 | tamoxifen | Mammary epithelium | Not mentioned 28. |

| Ah-CRE; LSL-ROCK2-ER | C57BL/6 | tamoxifen | Intestinal epithelium | Not mentioned 28. |

| CAG-CRE-ER; LSL-ROCK2-ER | C57BL/6 | tamoxifen | Most tissues in whole mice | Induces cerebral hemorrhagic lesions and death 28. |

|

LSL-KrasG12D;LSL-p53R172H; Pdx1-Cre; LSL ROCK2-ER |

Not mentioned | tamoxifen | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | Promotes tumor growth and invasion, reduces survival 29. |

Ah: cytochrome P450 1A1; CRE: Cre recombinase; ER: estrogen receptor; 4HT: 4-hydroxytamoxifen; K14: cytokeratin 14; LSL: loxP-STOP-loxP; MMTV: murine mammary tumor virus; Pdxl: pancreatic and duodenal homeobox gene 1; CAG: a synthetic promoter consisting of a cytomegalovirus early enhancer element, a chicken β-actin gene promoter with the first exon and intron, and a splice acceptor from the rabbit β-globin gene.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RR140081 and RR170721 to G.B.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81700319 to Jing.L., 81570255 to J. L.), Key Science and Technology Research Plan of Shandong Province (2017GSF218037 to J. L.) and Shandong Taishan Scholarship (to J. L.).

Abbreviations

- AJ

adherens junction

- AMPK

adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- AT1R

Ang II type 1 receptor

- AT2R

Ang II type 2 receptor

- CCM2

cerebral cavernous malformations 2

- EC

endothelial cell

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- ER

estrogen receptor

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- HMEC-1

human microvascular endothelial cell-1

- HNF4A

hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha

- HRMEC

human retinal microvascular endothelial cell

- HSP90

heat shock protein 90

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- IL-8

interleukin-8

- KRIT1

Krev interaction trapped protein 1

- LIMK

LIM motif-containing protein kinase

- LPA

lysophosphatidic acid

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MCP-1

monocyte chemotactic protein-1

- MEKK3

MAPK/ERK kinase kinase 3

- MLC

myosin light chain

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- MS1

mile sven 1

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- OIR

oxygen-induced retinopathy

- ox-LDL

oxidized low-density lipoprotein

- PAI-1

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PP2A

protein phosphatase-2A

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- PH

pleckstrin homology

- RBD

Rho-binding domain

- RhoA

ras homolog gene family member A

- RhoGEF

Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- ROCK

Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase

- SFK

Src family kinase

- Shh

sonic hedgehog

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TRPV4

transient receptor potential vanilloid 4

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR-2

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2

- VPF

vascular permeability factor.

References

- 1.Wu B, Zhang Z, Lui W, Chen X, Wang Y, Chamberlain AA. et al. Endocardial cells form the coronary arteries by angiogenesis through myocardial-endocardial VEGF signaling. Cell. 2012;151:1083–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chong DC, Yu Z, Brighton HE, Bear JE, Bautch VL. Tortuous Microvessels Contribute to Wound Healing via Sprouting Angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:1903–12. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson E, Zetterberg E, Vedin I, Hultenby K, Palmblad J, Mints M. Low pericyte coverage of endometrial microvessels in heavy menstrual bleeding correlates with the microvessel expression of VEGF-A. Int J Mol Med. 2015;35:433–8. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Palma M, Biziato D, Petrova TV. Microenvironmental regulation of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:457–74. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtenauer M, Jung C. Microvesicles and ectosomes in angiogenesis and diabetes - message in a bottle in the vascular ocean. Theranostics. 2018;8:3974–6. doi: 10.7150/thno.27154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koo T, Park SW, Jo DH, Kim D, Kim JH, Cho HY. et al. CRISPR-LbCpf1 prevents choroidal neovascularization in a mouse model of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1855. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04175-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Couchie D, Vaisman B, Abderrazak A, Mahmood DFD, Hamza MM, Canesi F. et al. Human Plasma Thioredoxin-80 Increases With Age and in ApoE(-/-) Mice Induces Inflammation, Angiogenesis, and Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2017;136:464–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yla-Herttuala S, Bridges C, Katz MG, Korpisalo P. Angiogenic gene therapy in cardiovascular diseases: dream or vision? Eur Heart J. 2017;38:1365–71. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimamura M, Nakagami H, Koriyama H, Morishita R. Gene therapy and cell-based therapies for therapeutic angiogenesis in peripheral artery disease. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:186215. doi: 10.1155/2013/186215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loirand G. Rho Kinases in Health and Disease: From Basic Science to Translational Research. Pharmacol Rev. 2015;67:1074–95. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.010595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maekawa M, Ishizaki T, Boku S, Watanabe N, Fujita A, Iwamatsu A. et al. Signaling from Rho to the actin cytoskeleton through protein kinases ROCK and LIM-kinase. Science. 1999;285:895–8. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahmann C, Schroeter T. Rho-kinase inhibitors as therapeutics: from pan inhibition to isoform selectivity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:171–7. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhowmick NA, Ghiassi M, Aakre M, Brown K, Singh V, Moses HL. TGF-beta-induced RhoA and p160ROCK activation is involved in the inhibition of Cdc25A with resultant cell-cycle arrest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15548–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536483100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka T, Nishimura D, Wu RC, Amano M, Iso T, Kedes L. et al. Nuclear Rho kinase, ROCK2, targets p300 acetyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15320–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510954200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakagawa O, Fujisawa K, Ishizaki T, Saito Y, Nakao K, Narumiya S. ROCK-I and ROCK-II, two isoforms of Rho-associated coiled-coil forming protein serine/threonine kinase in mice. FEBS Lett. 1996;392:189–93. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00811-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung T, Chen XQ, Manser E, Lim L. The p160 RhoA-binding kinase ROK alpha is a member of a kinase family and is involved in the reorganization of the cytoskeleton. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5313–27. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montalvo J, Spencer C, Hackathorn A, Masterjohn K, Perkins A, Doty C. et al. ROCK1 & 2 perform overlapping and unique roles in angiogenesis and angiosarcoma tumor progression. Curr Mol Med. 2013;13:205–19. doi: 10.2174/1566524011307010205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thumkeo D, Keel J, Ishizaki T, Hirose M, Nonomura K, Oshima H. et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse rho-associated kinase 2 gene results in intrauterine growth retardation and fetal death. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5043–55. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.5043-5055.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimizu Y, Thumkeo D, Keel J, Ishizaki T, Oshima H, Oshima M. et al. ROCK-I regulates closure of the eyelids and ventral body wall by inducing assembly of actomyosin bundles. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:941–53. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thumkeo D, Shimizu Y, Sakamoto S, Yamada S, Narumiya S. ROCK-I and ROCK-II cooperatively regulate closure of eyelid and ventral body wall in mouse embryo. Genes Cells. 2005;10:825–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamijo H, Matsumura Y, Thumkeo D, Koike S, Masu M, Shimizu Y. et al. Impaired vascular remodeling in the yolk sac of embryos deficient in ROCK-I and ROCK-II. Genes Cells. 2011;16:1012–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2011.01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bryan BA, Dennstedt E, Mitchell DC, Walshe TE, Noma K, Loureiro R. et al. RhoA/ROCK signaling is essential for multiple aspects of VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. FASEB J. 2010;24:3186–95. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-145102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rikitake Y, Oyama N, Wang CY, Noma K, Satoh M, Kim HH. et al. Decreased perivascular fibrosis but not cardiac hypertrophy in ROCK1+/- haploinsufficient mice. Circulation. 2005;112:2959–65. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.584623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noma K, Rikitake Y, Oyama N, Yan G, Alcaide P, Liu PY. et al. ROCK1 mediates leukocyte recruitment and neointima formation following vascular injury. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1632–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI29226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samuel MS, Munro J, Bryson S, Forrow S, Stevenson D, Olson MF. Tissue selective expression of conditionally-regulated ROCK by gene targeting to a defined locus. Genesis. 2009;47:440–6. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samuel MS, Lopez JI, McGhee EJ, Croft DR, Strachan D, Timpson P. et al. Actomyosin-mediated cellular tension drives increased tissue stiffness and beta-catenin activation to induce epidermal hyperplasia and tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:776–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kular J, Scheer KG, Pyne NT, Allam AH, Pollard AN, Magenau A. et al. A Negative Regulatory Mechanism Involving 14-3-3zeta Limits Signaling Downstream of ROCK to Regulate Tissue Stiffness in Epidermal Homeostasis. Dev Cell. 2015;35:759–74. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samuel MS, Rath N, Masre SF, Boyle ST, Greenhalgh DA, Kochetkova M. et al. Tissue-selective expression of a conditionally-active ROCK2-estrogen receptor fusion protein. Genesis. 2016;54:636–46. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rath N, Morton JP, Julian L, Helbig L, Kadir S, McGhee EJ. et al. ROCK signaling promotes collagen remodeling to facilitate invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma tumor cell growth. EMBO Mol Med. 2017;9:198–218. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riento K, Ridley AJ. Rocks: multifunctional kinases in cell behaviour. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:446–56. doi: 10.1038/nrm1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sebbagh M, Hamelin J, Bertoglio J, Solary E, Breard J. Direct cleavage of ROCK II by granzyme B induces target cell membrane blebbing in a caspase-independent manner. J Exp Med. 2005;201:465–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sebbagh M, Renvoize C, Hamelin J, Riche N, Bertoglio J, Breard J. Caspase-3-mediated cleavage of ROCK I induces MLC phosphorylation and apoptotic membrane blebbing. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:346–52. doi: 10.1038/35070019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng J, Ito M, Kureishi Y, Ichikawa K, Amano M, Isaka N. et al. Rho-associated kinase of chicken gizzard smooth muscle. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:3744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Araki S, Ito M, Kureishi Y, Feng J, Machida H, Isaka N. et al. Arachidonic acid-induced Ca2+ sensitization of smooth muscle contraction through activation of Rho-kinase. Pflugers Archiv European Journal of Physiology. 2001;441:596. doi: 10.1007/s004240000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gong C, Stoletov KV, Terman BI. VEGF treatment induces signaling pathways that regulate both actin polymerization and depolymerization. Angiogenesis. 2004;7:313–21. doi: 10.1007/s10456-004-7960-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hopkins AM, Pineda AA, Winfree LM, Brown GT, Laukoetter MG, Nusrat A. Organized migration of epithelial cells requires control of adhesion and protrusion through Rho kinase effectors. American journal of physiology Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2007;292:G806–17. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00333.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aburima A, Wraith KS, Raslan Z, Law R, Magwenzi S, Naseem KM. cAMP signaling regulates platelet myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation and shape change through targeting the RhoA-Rho kinase-MLC phosphatase signaling pathway. Blood. 2013;122:3533–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-487850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsui T, Maeda M, Doi Y, Yonemura S, Amano M, Kaibuchi K. et al. Rho-kinase phosphorylates COOH-terminal threonines of ezrin/radixin/moesin (ERM) proteins and regulates their head-to-tail association. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:647–57. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fukata Y, Oshiro N, Kinoshita N, Kawano Y, Matsuoka Y, Bennett V. et al. Phosphorylation of adducin by Rho-kinase plays a crucial role in cell motility. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:347–61. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.2.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukata Y, Oshiro N, Kaibuchi K. Activation of moesin and adducin by Rho-kinase downstream of Rho. Biophys Chem. 1999;82:139–47. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(99)00113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Couzens AL, Gill RM, Scheid MP. Characterization of a modified ROCK2 protein that allows use of N6-ATP analogs for the identification of novel substrates. BMC Biotechnol. 2014;14:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-14-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bergers G, Benjamin LE. Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:401–10. doi: 10.1038/nrc1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shweiki D, Itin A, Soffer D, Keshet E. Vascular endothelial growth factor induced by hypoxia may mediate hypoxia-initiated angiogenesis. Nature. 1992;359:843–5. doi: 10.1038/359843a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun HJ, Cai WW, Gong LL, Wang X, Zhu XX, Wan MY. et al. FGF-2-mediated FGFR1 signaling in human microvascular endothelial cells is activated by vaccarin to promote angiogenesis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;95:144–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mittermayr R, Slezak P, Haffner N, Smolen D, Hartinger J, Hofmann A. et al. Controlled release of fibrin matrix-conjugated platelet derived growth factor improves ischemic tissue regeneration by functional angiogenesis. Acta Biomater. 2016;29:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bruns CJ, Harbison MT, Davis DW, Portera CA, Tsan R, McConkey DJ. et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor blockade with C225 plus gemcitabine results in regression of human pancreatic carcinoma growing orthotopically in nude mice by antiangiogenic mechanisms. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1936–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Y, Yang G, Zhang J, Xing K, Dai L, Cheng L. et al. Anti-TNF-alpha monoclonal antibody reverses psoriasis through dual inhibition of inflammation and angiogenesis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;28:731–43. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li S, Dang Y, Zhou X, Huang B, Huang X, Zhang Z. et al. Formononetin promotes angiogenesis through the estrogen receptor alpha-enhanced ROCK pathway. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16815. doi: 10.1038/srep16815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khaidakov M, Mitra S, Wang X, Ding Z, Bora N, Lyzogubov V. et al. Large impact of low concentration oxidized LDL on angiogenic potential of human endothelial cells: a microarray study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oh MJ, Zhang C, LeMaster E, Adamos C, Berdyshev E, Bogachkov Y. et al. Oxidized LDL signals through Rho-GTPase to induce endothelial cell stiffening and promote capillary formation. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:791–808. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M062539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fischer RS, Gardel M, Ma X, Adelstein RS, Waterman CM. Local cortical tension by myosin II guides 3D endothelial cell branching. Curr Biol. 2009;19:260–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilkins JR, Pike DB, Gibson CC, Li L, Shiu YT. The interplay of cyclic stretch and vascular endothelial growth factor in regulating the initial steps for angiogenesis. Biotechnol Prog. 2015;31:248–57. doi: 10.1002/btpr.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holmes DI, Zachary I. The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family: angiogenic factors in health and disease. Genome Biol. 2005;6:209. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-2-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Claesson-Welsh L. Signal transduction by vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:20–4. doi: 10.1042/bst0310020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Koolwijk P, Versteilen A, van Hinsbergh VW. Involvement of RhoA/Rho kinase signaling in VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis in vitro. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:211–7. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000054198.68894.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zeng H, Zhao D, Mukhopadhyay D. KDR stimulates endothelial cell migration through heterotrimeric G protein Gq/11-mediated activation of a small GTPase RhoA. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46791–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206133200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yin L, Morishige K, Takahashi T, Hashimoto K, Ogata S, Tsutsumi S. et al. Fasudil inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1517–25. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Doyle B, Caplice N. Plaque neovascularization and antiangiogenic therapy for atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2073–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dandapat A, Hu C, Sun L, Mehta JL. Small concentrations of oxLDL induce capillary tube formation from endothelial cells via LOX-1-dependent redox-sensitive pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2435–42. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.152272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carbajo-Lozoya J, Lutz S, Feng Y, Kroll J, Hammes HP, Wieland T. Angiotensin II modulates VEGF-driven angiogenesis by opposing effects of type 1 and type 2 receptor stimulation in the microvascular endothelium. Cell Signal. 2012;24:1261–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simoncini T, Scorticati C, Mannella P, Fadiel A, Giretti MS, Fu XD. et al. Estrogen receptor alpha interacts with Galpha13 to drive actin remodeling and endothelial cell migration via the RhoA/Rho kinase/moesin pathway. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1756–71. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oviedo PJ, Sobrino A, Laguna-Fernandez A, Novella S, Tarin JJ, Garcia-Perez MA. et al. Estradiol induces endothelial cell migration and proliferation through estrogen receptor-enhanced RhoA/ROCK pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;335:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gopal S, Garibaldi S, Goglia L, Polak K, Palla G, Spina S. et al. Estrogen regulates endothelial migration via plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1) Mol Hum Reprod. 2012;18:410–6. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gas011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ali MH, Schumacker PT. Endothelial responses to mechanical stress: where is the mechanosensor? Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S198–206. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ingber DE. Mechanical signaling and the cellular response to extracellular matrix in angiogenesis and cardiovascular physiology. Circ Res. 2002;91:877–87. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000039537.73816.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seetharaman S, Etienne-Manneville S. Integrin diversity brings specificity in mechanotransduction. Biol Cell. 2018;110:49–64. doi: 10.1111/boc.201700060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dorland YL, Huveneers S. Cell-cell junctional mechanotransduction in endothelial remodeling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74:279–92. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2325-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Izawa Y, Gu YH, Osada T, Kanazawa M, Hawkins BT, Koziol JA. et al. beta1-integrin-matrix interactions modulate cerebral microvessel endothelial cell tight junction expression and permeability. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38:641–58. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17722108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li S, Chen BP, Azuma N, Hu YL, Wu SZ, Sumpio BE. et al. Distinct roles for the small GTPases Cdc42 and Rho in endothelial responses to shear stress. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1141–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI5367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shiu YT, Li S, Marganski WA, Usami S, Schwartz MA, Wang YL. et al. Rho mediates the shear-enhancement of endothelial cell migration and traction force generation. Biophys J. 2004;86:2558–65. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ghosh K, Thodeti CK, Dudley AC, Mammoto A, Klagsbrun M, Ingber DE. Tumor-derived endothelial cells exhibit aberrant Rho-mediated mechanosensing and abnormal angiogenesis in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11305–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800835105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thodeti CK, Matthews B, Ravi A, Mammoto A, Ghosh K, Bracha AL. et al. TRPV4 channels mediate cyclic strain-induced endothelial cell reorientation through integrin-to-integrin signaling. Circ Res. 2009;104:1123–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hartmannsgruber V, Heyken WT, Kacik M, Kaistha A, Grgic I, Harteneck C. et al. Arterial response to shear stress critically depends on endothelial TRPV4 expression. PLoS One. 2007;2:e827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thoppil RJ, Cappelli HC, Adapala RK, Kanugula AK, Paruchuri S, Thodeti CK. TRPV4 channels regulate tumor angiogenesis via modulation of Rho/Rho kinase pathway. Oncotarget. 2016;7:25849–61. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ueda T, Shikano M, Kamiya T, Joh T, Ugawa S. The TRPV4 channel is a novel regulator of intracellular Ca2+ in human esophageal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301:G138–47. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00511.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.van der Meel R, Symons MH, Kudernatsch R, Kok RJ, Schiffelers RM, Storm G. et al. The VEGF/Rho GTPase signalling pathway: a promising target for anti-angiogenic/anti-invasion therapy. Drug Discov Today. 2011;16:219–28. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Howe GA, Addison CL. RhoB controls endothelial cell morphogenesis in part via negative regulation of RhoA. Vasc Cell. 2012;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2045-824X-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim C, Yang H, Fukushima Y, Saw PE, Lee J, Park JS. et al. Vascular RhoJ is an effective and selective target for tumor angiogenesis and vascular disruption. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:102–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]