Abstract

The most promising anti-tumor agent developed in the past three decades is Taxol. It is proven to be effective against many cancers. It is necessary to isolate pharmacologically potent endophytic microbial strains from medicinal plants with special reference to Taxol production. In the current study, endophytic fungi were isolated from the bark of the medicinal plant, Salacia oblonga. The isolated endophytes were identified morphologically, and further characterized by ITS-PCR using genomic DNA samples, later the products were sequenced for identification and phylogenetic linkage mapping. The samples were screened for the potential to produce Taxol or taxanes, employing PCR. The resulted data have been sequenced to confirm the presence of the two genes implicated in Taxol biosynthesis, 10-deacetylbaccatin III-10-O-acetyl transferase (DBAT) and C-13 phenylpropanoid side chain-CoA acyltransferase (BAPT). Seven samples showed the amplicons of DBAT gene and one showed the amplicons of BAPT gene. Sequencing of these products was carried out, of which one sample has revealed sequence homology to the original DBAT gene from Taxus. The present work confirms and substantiates the potential of genomic mining approach to discover novel Taxol-producing endophytic fungi.

Keywords: Endophytes, Gene sequencing, Genomic mining, ITS-PCR, Salacia oblonga, Taxol

1. Introduction

Salacia oblonga is a tropical woody plant/shrub found in the forests of South Asian countries, including Sri Lanka and India. It is commonly known as ‘Saptrangi’ or ‘Saptachakra’. The roots and stems of S. oblonga have been used extensively in Ayurveda and traditional Indian medicine for the treatment of Diabetes [1]. S. oblonga extracts have long known to have hypoglycemic, hypolipidemic, anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties [2], [3], [4]. It has also been reported to have potential anticancer properties showing antitumor activity against EAT cells [5].

In recent times, molecular techniques are being used extensively in biodiversity studies of endophytes due to their sensitivity and specificity. Further, they are very rapid and economical, these are not affected, or dependent on environmental factors likes culture conditions. Analysis of DNA extracted from fungi has been used widely as a means of identification and screening of fungi for their potential to produce certain desired metabolites [6]. Secondary metabolites are produced from several intermediate products that accumulate, either in the culture media or within the cells (during primary metabolism). Production of secondary metabolites is significantly affected by genetic, developmental and environmental factors [7].

The structural diversity of secondary metabolites is a result of modifications and combinations of reactions from primary metabolic pathways. Secondary metabolites may be found in various species in disparate genera or families, and a variety of metabolites can be expressed from a single species under different environmental conditions [8]. The groups commonly distributed in nature are the polyketides, terpenes, steroids, shikimic acid and alkaloids. Most secondary metabolites are low molecular weight compounds having molecular masses less than 1500 Da [9]. Conventional morphological characterization of fungal endophytes has the drawback of difficulty in identifying the species which have structural similarity. Furthermore, these are very difficult in fungal isolates that fail to sporulate in culture [10]. Molecular methods were successfully employed in identifying microorganisms at diverse hierarchical taxonomic levels due to their high sensitivity, specificity and quicker procedures. Most of the endophytic fungi can be detected and identified based on comparative analyses of the ribosomal DNA sequences, especially the ITS region [11], [12], [13].

The diterpenoid “Taxol” (Paclitaxel) have gained more attention and interest than any other drug since its discovery mainly due to its unique mode of action compared to any other anticancer agents. This compound affects the multiplication of cancer cells by interfering with the cell cycle, hence, reducing their growth and spread. Food and drug administration (FDA) has approved Taxol for the advanced treatment of various cancers [14].

Taxol is a diterpenoid originally isolated from the stem/bark of the Pacific Yew tree (Taxus brevifolia, Nutt.; Taxaceae family). Several other species of Taxus have also been reported to produce Taxol [15]. Taxol has become a widely used anti-cancer drug for the treatment of various cancers. Besides, it is also effective against non-cancerous conditions like polycystic kidney diseases [16]. The production of Taxol from the T. brevifolia bark is limited (0.01–0.05%) because, the plant is not abundantly found in nature and grows slowly and also it results in low yield of Taxol per gram. Further, it results in the death of the tree due to the removal of the bark. Hence, alternate methods for Taxol production have been explored, such as production by chemical synthesis, semi-synthesis (chemical modification of Taxol precursors), plant cell and tissue culture and also by fermentation using endophytic fungi [17]. Extraction of Taxol from endophytic fungus has established high potential in increasing the efficiency of Taxol production and other cancer treatment products [18], [19].

Taxol is a polyoxygenated cyclic diterpenoid characterized by the taxane ring system and it differs from other known taxanes either in the substitution pattern, the nature of the ester side chains, or in the presence of the oxetane ring (D-ring) system. Potent antimitotic activity seems to be restricted to taxanes, like Taxol, which possess an N-benzoyl-3-phenylisoserineside-chain at C-13, the oxetane ring function, and a benzoyl group at C-2. Similar to other terpenoids of plastid origin, Taxol biosynthesis follows the mevalonate-independent (1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate) pathway, which operates in parallel with cytosolic acetate/mevalonate pathway for the biosynthesis of isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP). On the other hand, the IPP derived from the plastid 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate pathway is used in the biosynthesis of carotenoids, phytol, plastoquinone, isoprene, monoterpenes, and diterpenes [20].

Due to the increased demand of the Taxol production the current study has been undertaken to identify the Taxol producing gene from the fungal endophytes isolated from S. oblonga.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sampling

Plant materials S. oblonga was collected in the early monsoon season and brought to the laboratory in polythene bags from the village Kigga, Sringeri Taluk, Chikmagalore district, Karnataka, India (Western Ghats).

2.2. Isolation of endophytes

Samples of S. oblonga were washed in running tap water to remove adhered soil particles to it. Then, the plants samples were processed under laminar chamber using 70% (v/v) ethanol for 30 s and 3.5% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite for 3–5 min for the surface sterilization. Later, they were washed thoroughly using sterile distilled water. The plant materials were aseptically cut into small pieces and were plated on water agar medium (0.15%, w/v) containing 1% (w/v) Chloramphenicol. The plates were incubated at 25 ± 3 °C for 21 days.

Pure cultures of 34 endophytic fungal samples were isolated from the bark of S. oblonga. Pure cultures of samples were grown on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA), the culture was used for identification, characterization and further genetic analysis.

2.3. Endophyte characterization and identification

All 34 endophyte cultures were used for identification. Morphological characteristics of the various endophytic colonies were noted. The colony characteristics and morphology were examined by microscopy (Zeiss AX10 Imager A2, Zeiss, Germany) using lactophenol cotton blue staining. Some of their characteristics were identified with the help of the standard manual for identification of endophytes [21].

2.4. Subculturing of endophytes for DNA extraction

The 34 isolates were subcultured into the flasks containing 40 ml of potato dextrose broth (PDB) containing Ampicillin (0.5 mg/L). The bottles were left standing undisturbed for incubation at room temperature for one week to allow mycelial growth.

2.5. DNA isolation from cultured endophytes

Post incubation, mycelia were removed from the PDB, dried on filter paper and stored at −80 °C. DNA was extracted from 0.5 to 1.0 g of fresh mycelia according to the modified method of Saghai-Maroof et al. [22].

The isolated DNA was estimated by spectrophotometric methods employing NANODROP, 2000C spectrophotometer (Thermo SCIENTIFIC, Japan), using sterile triple distilled water as the blank. A portion of the genomic DNA was diluted to 50 ng/μl for use in PCR and stored at −20 °C for further use.

2.6. PCR amplification of ITS region

The target regions of the rDNA ITS1, ITS2 regions and 5.8S gene were amplified symmetrically using primers ITS 1 (5-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3) and ITS 4 (5-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3) [23]. Amplifications were performed in a total reaction volume of 25 μl containing 0.4 mM of dNTP mix, 10 pmol/μl of each primer, 2.5 μl of 10X PCR buffer, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 1.5 unit Taq DNA polymerase (Bangalore Genei, India) and 50 ng of template DNA. PCR amplifications were performed in a thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Germany) with an initial denaturing step of 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 amplification cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 90 s and a final extension step of 72 °C for 10 min. PCR amplification products were electrophoretically separated on 1.0% (w/v) agarose gels.

The above procedure for ITS PCR was repeated for these samples scaling up to a 50 μl reaction volume, 5 μl was used for agarose gel electrophoresis and the remaining volume of samples were sent for sequencing (Eurofins Genomics India, Bangalore, India).

2.7. PCR amplification for screening of potential Taxol-producing fungi

The genes coding for 10-deacetylbaccatin III-10-O-acetyl transferase (DBAT) and C-13 phenylpropanoid side chain-CoA acyltransferase (BAPT) was used as molecular markers to screen Taxol producing endophytic fungi. DBAT catalyzes the formation of baccatin III, the immediate diterpenoid precursor of Taxol (Walker and Croteau 2000). BAPT catalyzes the selective 13-O-acylation of baccatin III with b-phenylalanoyl-CoA as the acyl donor to form N-debenzoyl-20-deoxytaxol, i.e. it catalyzes the attachment of the biologically important Taxol side chain precursor. Based on the conserved sequence of the DBAT gene, primers DBAT-F (5-GGGAGGGTGCTCTGTTTG-3) and DBAT-R (5-GTTACCTGAACCACCAGAGG-3) were designed and synthesized according to Zhang et al. [24]. The primers BAPT-F (5-CCTCTCTCCGCCATTGACAA-3) and BAPT-R (5-TCGCCATCTCTGCCATACTT-3) were designed and synthesized according to Li et al. [25].

The fungal isolates were initially screened by PCR for the presence of the DBAT gene. PCR amplification was carried out using the primers DBAT-F and DBAT-R in a 25 μl reaction mixture containing 0.4 mM of dNTP mix, 10 pmol/μl of each primer, 2.5 μl of 10X PCR buffer, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 units Taq DNA polymerase (Bangalore Genei, India) and 50 ng of template DNA. PCR amplifications were performed in a thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Germany) with an initial denaturing step of 95 °C for 6 min, followed by 35 amplification cycles of 94 °C for 50 s, annealing at 50 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 50 s and a final extension step of 72 °C for 10 min. The amplified DNA fragments were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and those fungi showing amplicons for the DBAT gene were selected for sequencing and the next screening. For sequencing, the above procedure for DBAT PCR was repeated for these samples scaling up to a 50 μl reaction volume, 5 μl was used for agarose gel electrophoresis and the remaining volume of samples were sent for sequencing to Eurofins Genomics India, Bangalore, India. Fungi containing the DBAT gene were also screened again by PCR analysis for the gene coding for BAPT.

PCR amplification of the BAPT gene was carried out using the primers BAPT-F and BAPT-R in a 25 μl reaction mixture containing 0.4 mM of dNTP mix, 10 pmol/μl of each primer, 2.5 μl of 10X PCR buffer, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 units Taq DNA polymerase (Bangalore Genei, India) and 50 ng of template DNA. PCR amplifications were performed in a thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Germany) with an initial denaturing step of 95 °C for 6 min, followed by 35 amplification cycles of 94 °C for 50 s, annealing at 55 °C for 50 s, and extension at 72 °C for 50 s and a final extension step of 72 °C for 10 min. The amplified DNA fragments were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The primers used for the current study is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used for the study.

2.8. Gel electrophoresis

Genomic DNA samples, as well as ITS, PKS, DBAT and BAPT PCR amplification products were electrophoretically separated on 1.0% (w/v) agarose gels. 1.5% (w/v) agarose gels were used for DBAT PCR amplification products, as a lower molecular weight amplicon (∼200 bp) was expected. Electrophoresis was carried out and visualized under 300 nm UV light and documented using an imaging system (Molecular Imager, Gel-Doc XR+, BIORAD, USA). A 100 bp size marker was used as a reference (Bangalore Genei, India).

2.9. Sequence analysis

Base-calling of the received sequence data was done using Chroma Lite v2.01 software (http://technelysium.com.au), with conversion to FASTA format.

2.9.1. Species identification using BLAST

The fungal species were identified by using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) sequence analysis tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). The ITS sequence was compared using nucleotide BLAST with default settings and megablast (highly similar sequences) as the selected program. Species identification was determined from the lowest expect value (E-value) of the BLAST output and the similarity percentage. Occasionally, the BLAST search with the query sequence hit sequences from two different species with the same identity percentage. Under these conditions, the identification of the unknown sequences was made using the highest bit (max) score of listed species [26].

2.9.2. Phylogenetic analysis

The selected sequences were aligned using CLUSTAL W2 software [27]. The data were then processed for phylogenetic analysis using both maximum parsimony (MP) and neighbor joining (NJ) approaches. MP and NJ searches were carried out using MEGA 5.05 software [28] on a Windows XP Computer. Bootstrap analysis, which involves the use of random changes in nucleotide sequence followed by reconstruction of the tree, done to assess the reliability of the trees obtained.

2.9.3. Sequence identification using BLAST

Sequence identification of DBAT positive samples was attempted by searching databases using the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST sequence analysis tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). The sequence was compared using nucleotide–nucleotide BLAST (blastn) with default settings. Sequence similarity was determined on the basis of value (E-value) of the BLAST output and the similarity percentage. Homology determination was also attempted by using BLAST for comparison of the sequence to the known primer amplified section of the DBAT sequence (GenBank No. EF028093).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Endophyte characterization and identification

The fungi were identified morphologically and for some samples the aid of ITS sequence identification was used for verification. The most common endophyte was Alternaria spp. Other common species included Fusarium sp. (6 samples), of which one was identified as Fusarium solani and Aspergillus niger (6 samples). Other species identified included Botryosphaeria rhodina, Trichoderma longibrachiatum, Lasiodiplodia theobromae, Aspergillus terreus, Armilaria sp., Phoma sp., Coriolopsis caperata and Phomopsis sp. (Table 2).

Table 2.

Fungal endophytes isolated from Salacia oblonga.

| Sample code | Species | Sample code | Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| GR1 | Botryosphaeria rhodina | GR17 | Fusarium sp. |

| GR2 | Trichoderma longibrachiatum | GR 18 | Alternaria sp. |

| GR3 | Alternaria sp. | GR 19 | Armilaria sp. |

| GR4 | Fusarium sp. | GR20 | Fusarium sp. |

| GR5 | Alternaria sp | GR 21 | Alternaria sp. |

| GR6 | Lasiodiplodia theobromae | GR22 | Aspergillus niger |

| GR7 | Alternaria sp. | GR23 | Aspergillus niger |

| GR8 | Alternaria sp. | GR24 | Phoma sp. |

| GR9 | Alternaria sp. | GR 25 | Aspergillus niger |

| GR10 | Alternaria sp. | GR26 | Fusarium sp. |

| GR11 | Lasiodiplodia theobromae | GR27 | Aspergillus niger |

| GR12 | Aspergillus niger | GR28 | Aspergillus niger |

| GR13 | Alternaria sp. | GR29 | Phoma sp. |

| GR14 | Fusarium sp. | GR30 | Coriolopsis caperata |

| GR15 | Unidentified | GR31 | Phomopsis sp. |

| GR16 | Aspergillus terreus | GR32 | Aspergillus niger |

| GR33 | Alternaria sp. | GR34 | Fusarium solani |

3.2. Subculturing

While subculturing on PDB, proper growth was not observed in a few cultures (9, 15, 16, 19, 25, and 28), hence these have been excluded. Other samples were processed for further studies.

3.3. DNA extraction

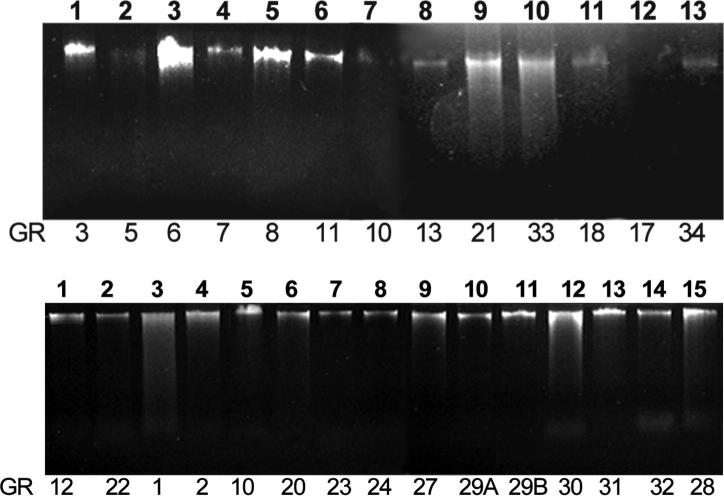

Agarose gel electrophoresis showed the DNA bands which confirms the DNA extracted from the isolates (Fig. 1). Estimation of DNA was carried out employing the spectroscopic method and the results (concentration and its purity) obtained are tabulated in Table 4.

Figure 1.

Isolated DNA of endophytic fungal isolates on 1% (w/v) agarose gel.

Table 4.

Summary of the results.

| No. | Sample code | DNA conc. (ng/μl) | A260/A280 | ITS | DBAT | BAPT | Sequencing |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | DBAT | |||||||

| 1 | GR 3 | 202.1 | 1.53 | +++ | ++++ | ✓ | ||

| 2 | GR 5 | 104.5 | 1.43 | +++ | ++++ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 3 | GR 6 | 205.4 | 1.48 | ++++ | ✓ | |||

| 4 | GR 7 | 72.5 | 1.52 | ++++ | ||||

| 5 | GR 8 | 141.8 | 1.58 | +++ | ||||

| 6 | GR 11 | 105.8 | 1.58 | ++++ | ✓ | |||

| 7 | GR 10 | 279.1 | 1.41 | ++++ | ||||

| 8 | GR 13 | 132.4 | 1.51 | ++++ | ||||

| 9 | GR 21 | 198.0 | 1.30 | ++++ | ||||

| 10 | GR 33 | 252.1 | 1.53 | ++++ | ||||

| 11 | GR 18 | 313.9 | 1.65 | ++++ | ||||

| 12 | GR 12 | 188.9 | 1.27 | |||||

| 13 | GR 22 | 109.7 | 1.33 | + | ||||

| 14 | GR 23 | 180.7 | 1.19 | +++ | ✓ | |||

| 15 | GR 27 | 221.9 | 1.31 | |||||

| 16 | GR 32 | 503.3 | 1.19 | |||||

| 17 | GR 4 | 8.5 | 1.36 | |||||

| 18 | GR 14 | 13.8 | 1.64 | |||||

| 19 | GR 17 | 48.6 | 1.51 | +++ | + | |||

| 20 | GR 20 | 138.9 | 1.92 | +++ | + | |||

| 21 | GR 26 | – | – | |||||

| 22 | GR 34 | 108.4 | 1.50 | +++ | ++ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 23 | GR 1 | 277.3 | 1.66 | +++ | + | + | ✓ | ✓ |

| 24 | GR 2 | 212.0 | 1.79 | ++++ | ++ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 25 | GR 24 | 1165.2 | 1.09 | − | ||||

| 26 | GR 29B | 254.4 | 1.62 | ++ | ✓ | |||

| 27 | GR 30 | 1403.4 | 1.96 | ++++ | ++ | ✓ | ||

| 28 | GR 31 | 306.0 | 1.83 | ++++ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

3.4. PCR amplification of ITS region

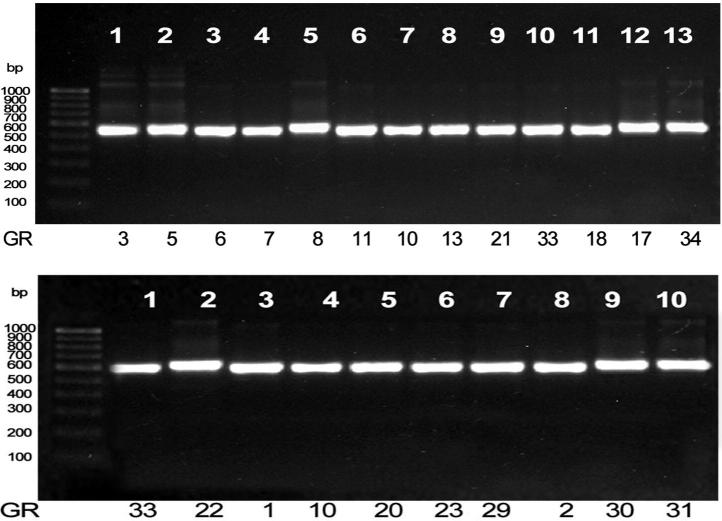

PCR reaction was carried out for amplification of ITS regions for the samples that has resulted in a good amount of DNA yield. The reaction mixtures after PCR were loaded on an agarose gel and after separation the gel was documented. The Samples GR1, GR2, GR3, GR5, GR6, GR7, GR8, GR10, GR11, GR13, GR17, GR18, GR20, GR21, GR22, GR23, GR29, GR30, GR31, GR33, and GR34 have showed bands of 500–600 bp (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

ITS PCR products of endophytic fungal isolates on 1% (w/v) agarose gel.

3.5. PCR amplification for screening for DBAT and BAPT genes

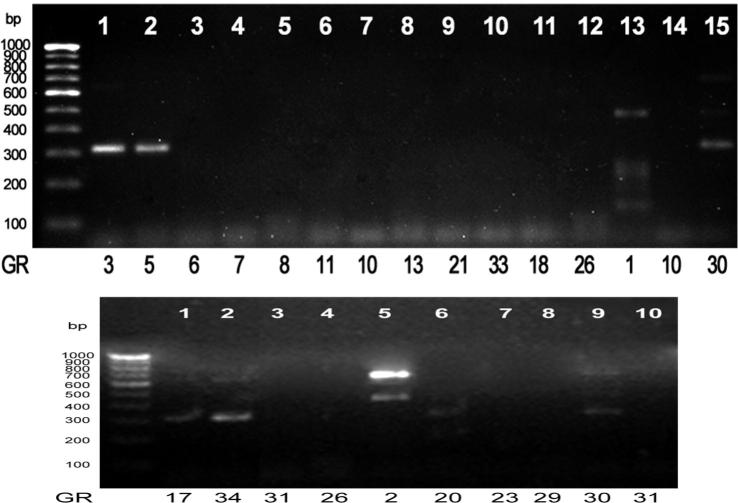

3.5.1. DBAT

PCR amplification was carried out for specific gene DBAT using all samples. Among those samples GR3, GR5, GR17, GR34, GR1, GR2, GR20 and GR30 have shown positive results for DBAT. Multiple bands were observed in the sample GR2 (∼480 bp and ∼700 bp) and GR30 (∼320 bp, ∼460 bp and ∼780 bp). Sample GR3 and GR5 have shown a band with molecular weight ∼410 bp, whereas GR1 has shown a band at ∼460 bp. GR17 and GR34 have shown a band at ∼320 bp. Sample GR2 has shown two bands at ∼480 bp and ∼700 bp. GR20 has shown a band at ∼360 bp (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

PCR screening of endophytic fungal isolates for the DBAT gene.

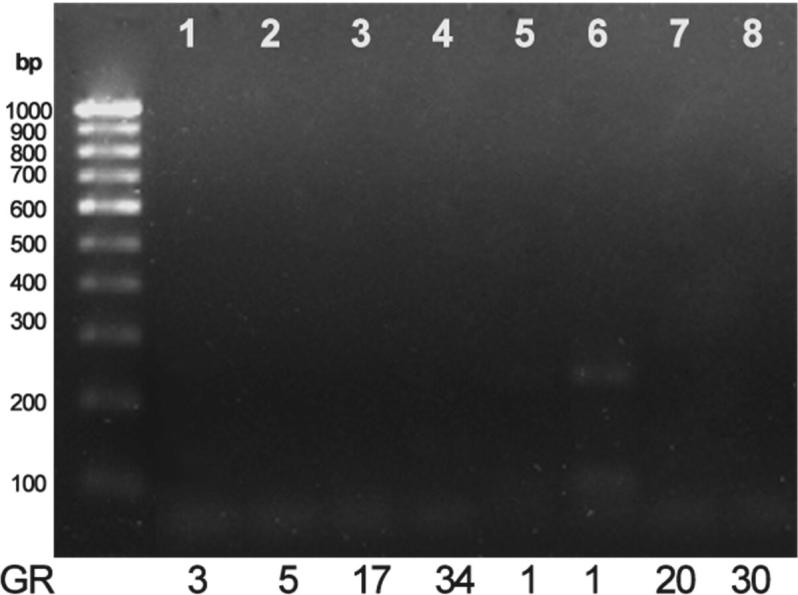

3.5.2. BAPT

The samples that were positive for DBAT (7 samples) were selected for conducting PCR to screen for specific gene BAPT. Only one sample, GR1 has shown a band corresponding to ∼230 bp (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

PCR screening of endophytic fungal isolates for the BAPT gene.

3.6. Sequence analysis

3.6.1. Species identification using BLAST

nBLAST using previously mentioned parameters enabled species identification. All sequences were identified using megablast as the selected algorithm, except GR31 because there was no similarity using this option. Hence, the nBLAST algorithm was chosen to define the sequence and the isolate was identified as Phomopsis sp. Chromatogram and sequence data obtained.

Based on the obtained BLAST result, the isolates were identified as represented in Table 3 with their respective identification result based on the previously mentioned parameters.

Table 3.

Species identification based on ITS nBLAST result.

| Sample code | Size (bp) | E-value | Max. ident. (%) | Bit (max) score | Query coverage (%) | Organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GR 1 | 650 | 0.0 | 95 | 998 | 97 | Botryosphaeria rhodina |

| GR 2 | 650 | 0.0 | 96 | 974 | 92 | Trichoderma longibrachiatum |

| GR 6 | 550 | 0.0 | 100 | 909 | 89 | Lasiodiplodia theobromae |

| GR 11 | 550 | 0.0 | 100 | 905 | 89 | Lasiodiplodia theobromae |

| GR 23 | 750 | 0.0 | 94 | 1127 | 98 | Aspergillus niger |

| GR 30 | 700 | 0.0 | 99 | 1075 | 93 | Coriolopsis caperata |

| GR 31 | 600 | 5e−67 | 73 | 264 | 83 | Phomopsis sp. |

| GR 34 | 550 | 0.0 | 99 | 917 | 91 | Fusarium solani |

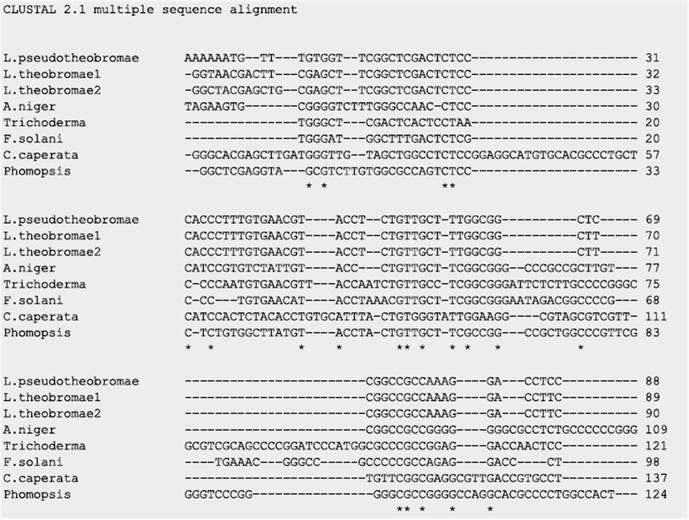

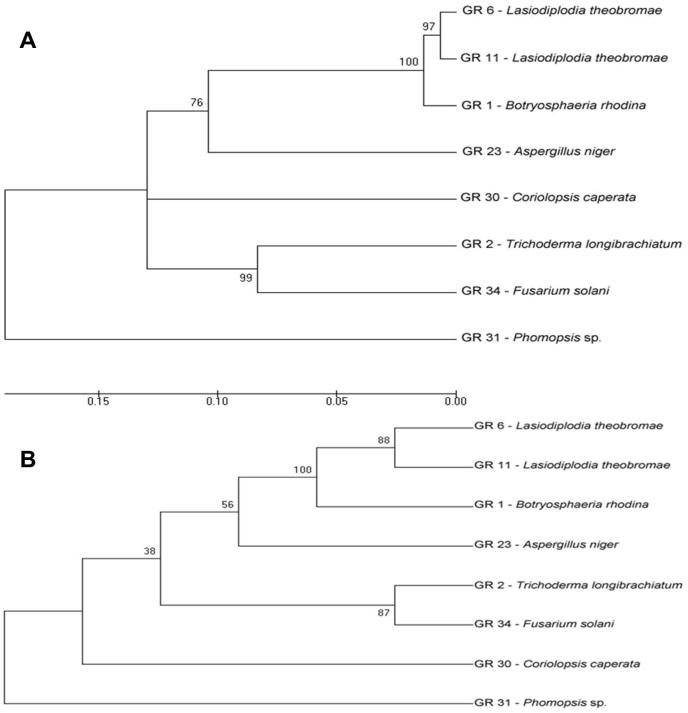

3.6.2. Phylogenetic analysis

CLUSTAL W2 software enabled sequence alignment, a prerequisite for phylogenetic analysis. CLUSTAL W2 sequence alignment was carried out using NJ (Neighbor Joining) algorithm. Dashes (–) correspond to insertions or deletions asterisks (∗) correspond to fully conserved nucleotides (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

CLUSTAL W2 output.

A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the aligned sequence of partial ITS region. Evolutionary analysis were conducted in MEGA 5.05 by using Neighbor-Joining (NJ) and Maximum Parsimony (MP) analysis (Fig. 6(A and B), respectively). Bootstrap analysis was also carried out to assess the reliability of the tree. Each number indicates the percentage of bootstrap samplings derived from 1000 samples, supporting the internal branches.

Figure 6.

Evolutionary relationships of taxa using Neighbor-Joining (NJ) and Maximum Parsimony (MP) analysis (A and B, respectively).

Based on BLAST result, GR6 and GR11 correspond to L. theobromae, but both evolutionary trees do not show them as the same species; thus both isolates might differ at the subspecies level. Isolates GR6 and GR11 are siblings in 97% and 88% of the bootstrap replications based on NJ method and MP method, respectively. GR2 (T. longibrachiatum) and GR34 (F. solani) are related at 99% (NJ method) and 87% (MP method) bootstrap support. Interestingly, both L. theobromae isolates and B. rhodina are located in the same larger clade with 100% support which means that all these isolates are closely related based on the ITS region sequences.

3.6.3. Sequence identification using BLAST

Sequencing revealed that there was some degree of non-specific amplification in the samples. Further processing using the available sequence was attempted nonetheless. However, nBLAST of DBAT amplification products produced no significant hits, even when search parameters were made less stringent. Next, two-sequence local alignment was attempted using the sequences and the known primer amplified the section of the DBAT sequence was done. Using this method, the sample GR1 alone revealed some degree of sequence homology, showing an E-value of 2e−04, query coverage of 57% and a score of 255, although the maximum alignment score observed was low (28.3).

4. Conclusion

Species characterization and identification using morphology and ITS sequence data revealed that the dominant species in the samples were Alternaria, Fusarium and Aspergillus niger. ITS PCR showed that the samples had amplicon of different sizes between 500 and 600 bp, demonstrating conclusively that there are samples from various species. Phylogenetic analysis based on the ITS DNA sequences using the MEGA 5.05 software using NJ and MP methods also helps for the construction of a phylogenetic tree. The obtained result is summarized in Table 4.

PCR banding of seven samples has been observed with the DBAT primers. Thus, assuming that the sequences are related enough and not the product of very low primer specificity, these samples may produce baccatin III or a related compound. Sequence analysis of these bands revealed that there was a non-specific amplification, which leads to less than ideal sequence data and thus analysis results. However, one sample showed some degree of sequence similarity to the known amplified section of the original DBAT sequence, and it is possible that the two may share a more distant relation. One sample has shown banding for BAPT gene, that indicates, it would be likely that the endophyte is capable of producing Taxol or a related compound. May be some of the samples showing amplification with the DBAT primers produce a Taxol precursor, such as baccatin III or a similar product, which may in turn produce a taxane. An alternative possibility is that this precursor may be used for the semisynthetic production of a taxane/Taxol.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support from Ministry of Human Resource and Development and University Grant commission under Institution of Excellence (IOE) Scheme awarded to the University of Mysore. One of the authors Dr. M.C. Madhusudhan gratefully acknowledges UGC, Government of India for Dr. D.S. Kothari Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of National Research Center, Egypt.

References

- 1.Williams J.A., Choe Y.S., Noss M.J., Baumgartner C.J., Mustad V.A. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;86(1):124–130. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chawla A., Singh S., Sharma A.K. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Biomed. Sci. 2013;4(4):1215–1228. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel P., Harde P., Pillai J., Darji N., Patel B. Pharmacophore. 2012;3(1):18–29. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh N.K., Biswas A., Rabbani S.I., Devi K., Khanam S. Pharmacologyonline. 2009;21:127–133. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trivedi P.C. I.K. International Pvt Ltd.; New Delhi: 2006. Medicinal Plants: Traditional Knowledge. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeewon R., Itto J., Mahadeb D., Jaufeerally-Fakim Y., Wang K.H., Liu A.R. J. Mycol. 2013;2013:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jalgaonwala R.E., Mohite B.M., Mahajan R.T. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011;1(2):21–32. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shukla S.T., Habbu P.V., Kulkarni V.H., Jagadish K.S., Aprajita P.R., Sutariya V.N. Asian J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014;2(3):01–16. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steven R.L., Rafael S.B., Frank S.C., Arthur E.S. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012;45(2):288–297. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding X., Liu K., Deng B., Chen W., Li W., Liu F. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013;29(10):1831–1838. doi: 10.1007/s11274-013-1345-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tejesvi M.V., Kini K.R., Prakash H.S., Subbiah Ven, Shetty H.S. Fungal Divers. 2007;24:37–54. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruma K., Shailasree S., Sampath Kumara K.K., Niranjana S.R., Prakash H.S. World J. Agric. Sci. 2011;7(5):577–582. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Botella L., Diez J.J. Fungal Divers. 2011;47(1):9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pimentel M.R., Molina G., Dionisio A.P., Marostica M.R., Jr., Pastore G.M. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2011;2011:1–11. doi: 10.4061/2011/576286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malik S., Cusido R.M., Mirjalili M.H., Moyano E., Palazon J., Bonfill M. Process Biochem. 2011;46(1):23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Visalakchi S., Muthumary J. Int. J. Pharm. Bio Sci. 2010;1:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandra S. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;95(1):47–59. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strobel G.A. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:535–544. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou X., Zhu H., Liu L., Lin J., Tang K. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;86:1707–1717. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2546-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jennewein S., Croteau R. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001;57:13–19. doi: 10.1007/s002530100757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathur S.B., Kognsdal O. first ed. International Seed Testing Association; Copenhagen, Denmark: 2003. Common Laboratory Seed Health Testing Methods for Detecting Fungi. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saghai-Maroof M.A., Soliman K.M., Jorgensen R.A., Allard R.W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:8014–8018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.24.8014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White T.J., Bruns T., Lee S., Taylor J.W. P.C.R. Protoc. Guide Methods Appl. 1990;18:315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang P., Zhou P.P., Jiang C., Yu H., Yu L.J. Biotechnol. Lett. 2008;30(12):2119–2123. doi: 10.1007/s10529-008-9801-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J., Hu Y., Chen W., Lin Z. Biotechnol. Bull. 2006;S1:356–371. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leaw S.N., Chang H.C., Sun H.F., Barton R., Bouchara J.P., Chang T.C. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44(3):693–699. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.693-699.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larkin M.A., Blackshields G., Brown N.P., Chenna R., McGettigan P.A., McWilliam H., Higgins D.G. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(21):2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nai M., Kumar S. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]