Abstract

Mitochondrial dysfunction manifests in the pathogenesis of Huntington’s disease (HD), a fatal and inherited neurodegenerative disease. Dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) is the primary component of mitochondrial fission and becomes hyperactivated in various models of HD. We previously reported that inhibition of Drp1 hyperactivation by P110, a rationally designed peptide inhibitor of Drp1-Fis1 interaction, is protective in the HD R6/2 mouse model, which expresses a fragment of mutant Huntingtin (mHtt). In this study, we expand our work to test the effect of P110 treatment in HD knock-in (zQ175 KI) mice that express full-length mtHtt and exhibit progressive disease symptoms, reminiscent of human HD. We find that subcutaneously sustained treatment with P110 reduces movement deficits of mice. Moreover, the treatment attenuates striatal neuronal loss, microglial hyperactivity and white matter disorganization in zQ175 KI mice. These findings provide an additional line of evidence that inhibition of Drp1 hyperactivation is sufficient to reduce HD-associated neuropathology and behavioral deficits. We propose that manipulation of Drp1 hyperactivation might be a useful strategy to develop therapeutics for treating HD.

Keywords: Mitochondrial fission, Mitochondrial dysfunction, Huntington’s disease, Neuroprotection, Drp1

1. Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a fatal and inherited neurodegenerative disease, which is caused by abnormal expansion of CAG trinucleotide repeats in the exon 1 of the huntingtin (Htt) gene [1]. Even though the genetic cause of HD has been identified, the molecular mechanisms underlying HD are still poorly understood, and no treatment is currently available.

Mitochondrial dysfunction plays vital roles in the pathogenesis of HD [2]. Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles that are regulated by continuous mitochondrial fusion and mitochondrial fission [3]. Mitochondrial fission is controlled by dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) [4]. Drp1, a cytosolic GTPase, can translocate to the mitochondrial outer membrane by binding to mitochondrial fission adaptors, where it mediates mitochondrial division. We and others have shown that hyper-activation of Drp1 elicits excessive mitochondrial fission and fragmentation, which is associated with a wide range of mitochondrial damage, including mitochondrial depolarization, oxidative stress and energy depletion, ultimately leading to cellular apoptosis [5,6], necrosis [7,8] or autophagic cell death [9,10].

There are several mitochondrial fission adaptors that have been identified, including Mff (mitochondrial fission factor) [11], Mid49/51 (mitochondrial dynamics proteins of 49 and 51 kDa) [12] and Fis1 (mitochondrial fission one protein) [13]. While the binding activities of Drp1 and Mff or Drp1 and Mid49/51 seem to regulate physiological mitochondrial fission, the interaction between Drp1 and Fis1 mainly occurs under stressed conditions [14,15]. We recently developed the peptide inhibitor P110, which selectively inhibits the interaction between Drp1 and Fis1 under stressed conditions without affecting the physiological level of Drp1 [9,14,16]. We have demonstrated that treatment with P110 peptide abolished Drp1 translocation to the mitochondria and Drp1 polymerization, two markers of Drp1 hyperactivation, in models of HD [16], Parkinson’s disease (PD) [9,17], multiple sclerosis [18] and brain ischemia/reperfusion [8]. Notably, P110 treatment had no observed effects on animal behavioral status and survival rate of naïve mice [16,17], suggestive of less toxicity. Thus, P110 peptide is a unique inhibitor for suppressing Drp1 activation under pathological conditions without affecting Drp1 physiological function. We previously showed that treatment with P110 is neuroprotective in HD transgenic R6/2 mice that express a fragment of mtHtt [16]. However, whether inhibition of Drp1 hyperactivation protects against the chronic and progressive process of HD remains unknown. In the present study, we show that sustained treatment with P110 peptide reduces HD-associated neuropathology and behavioral deficits in zQ175 KI mice that express the human mutant Htt (mtHtt) allele with ~190 expanded CAG repeats within the mouse huntingtin gene. Our findings provide an additional line of evidence for the usefulness of P110 in the treatment of HD.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

The zQ175 knock-in mice (B6J.zQ175 KI, JAX stock number: 027410) breeders (C57BL/6J genetic background) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. The zQ175 knock-in (zQ175 KI) allele encodes the human HTT exon one sequence with a ~190 CAG repeat tract, replacing the mouse Htt exon 1. Heterozygous and wild-type (WT) mice were generated by crossing heterozygous zQ175 mice on a C57B/l6J background. The mice were mated, bred and genotyped in the animal facility of Case Western Reserve University. Male mice at the ages of 4, 8 and 12 months were used in the study. All mice were maintained at a 12-h light/dark cycle (on 6 a.m., off 6 p.m.).

All animal experiments were conducted by protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Case Western Reserve University and were performed based on the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Sufficient procedures were employed for reduction of pain or discomfort of subjects during the experiments.

2.2. P110 peptide treatment in zQ175 KI mice

The Drp1 peptide inhibitor P110 and control peptide TAT were synthesized by Ontores company (Hangzhou, China) (Product: P104966, Lot number: ON120414SF-01). As previously described [14,16,18,19], the peptides are synthesized as one polypeptide with TAT47–57 carrier in the following order: N-terminus-TAT–spacer (Gly-Gly)–cargo (Drp149–55)–C-terminus. The C-termini of the peptides are modified to C (O)-NH2 using Rink Amide AM resin to increase stability. Peptides were analyzed by analytical reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) mass spectrometry (MS) and purified by preparative RP-HPLC. The purity of peptides is >90% when measured by RP-HPLC Chromatogram. Lyophilized peptides are stored at −80 °C freezer and are dissolved in sterile water before use.

In our previous study, we have found that P110 treatment in the dosage of 0.5–3 mg/kg/day range were effective in a HD mouse model [16], a PD mouse model [20] and ischemic brain injury rat model [8]. Thus, in the current study, we chose to deliver the peptides at a rate of 3 mg/kg/day. Male zQ175 KI mice and their age-matched wild-type littermates (WT) were implanted with a 28-day osmotic pump (Alzet, Cupertino CA, Model 2004) containing TAT control peptide or P110 peptide. The mice were treated with the peptide P110 or control peptide TAT starting from 4 months of age, and the pumps were replaced once every month.

2.3. Behavioral analysis

All behavioral analyses were conducted by an experimenter who was blinded to genotypes and treatment groups.

Gross locomotor activity was assessed by open field testing in zQ175 mice and age-matched wild-type littermates at the ages of 4, 8 and 12 months during the dark phase of the 12-h light-dark cycle. The mice were brought to the testing room for about 30 min to acclimate. After acclimation, the mice were placed in the center of an activity chamber (Omnitech Electronics, Inc.) equipped with photobeam sensor and allowed to explore while being tracked by an automated beam system (Vertax, Omnitech Electronics Inc). The related data were analyzed by activity monitor software. One hour of distance was moved, and horizontal and vertical activities were recorded. Briefly, the computer software auto-records and calculates the total horizontal activity (units), vertical activity (units) and total travelled distance (cm) over the 1-h data collection period for each mouse.

To evaluate anxiety-like behavior, we assessed the ratio of time that the mice spent in the central and margin area, which reflects, at least in part, anxiety-related activity. A decrease in the time spent in the center of the area relative to that in the margin area indicates anxiogenic-like behavior, whereas an increase suggests anxiolytic-like behavior [21].

2.4. Immunofluorescence analysis

Mice were deeply anesthetized and transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Frozen brain sections (10 μm, coronal) were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in TBS-T buffer followed by blocking with 5% normal goat serum. The brain sections were then incubated with DARPP-32 antibody (Abcam ab40801, 1:500 dilution), anti-Iba1 antibody (Wako Chemicals 019–19741, 1:500 dilution), MBP antibody (Covance SMI-99P, 1:2000 dilution) or Neurofilament antibody (Sigma N4142, 1:500 dilution) overnight at 4 °C, followed by staining with Alex-488/568 goat anti-rabbit/mouse secondary antibody (Life Technologies, 1:2000 dilution). For quantification of Iba1 immunostaining, the images of 0.32 × 0.32 mm were collected from all of the brain sections. For the quantification of DARPP32, MBP and Neurofilament immune-staining, we analyzed the immunodensity of these proteins from an identically sized area of the brain section. All the analyses were quantitated using NIH image J software. The same image exposure times and threshold settings were used for sections from all treatment groups.

2.5. Western blot analysis

Mice striatum were minced and homogenized in total cell lysate buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor). Protein concentrations of the supernatant lysates were determined by Bradford assay and analyzed on standard SDS-PAGE experiment. The related antibodies are listed as follows: antibody for Drp1 (BD bioscience 61113, 1:1000); antibody for DARPP-32 (Abcam ab40801, 1:5000); antibody for β-Actin (Sigma A1978, 1:10000); antibodies of PSD95 (Cell Signaling 2507, 1:1000) and HRP-conjugated anti-mouse and rabbit secondary antibodies were from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 7.04 software. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for comparison of multiple groups. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was considered achieved when the value of p was <0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Treatment of P110 attenuates Drp1 hyperactivation in zQ1175 KI mice

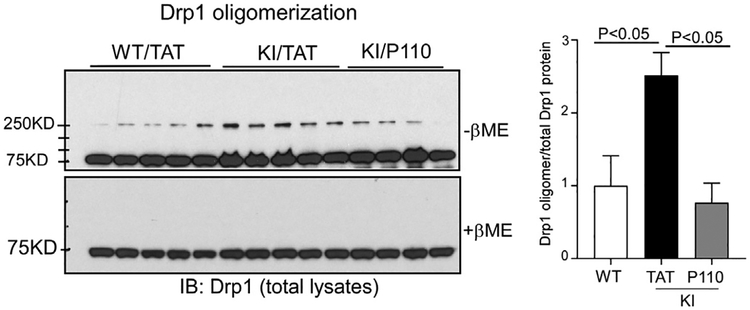

Upon translocation to the mitochondria, Drp1 assemblies oligomers to initiate mitochondrial fission [22]. For this reason, Drp1 oligomerization has been used as a marker of Drp1 hyperactivation in HD [16]. To validate the effect of P110 treatment on inhibition of Drp1 hyperactivation in the zQ175 KI mouse model, we examined Drp1 oligomerization in the striatal tissues of zQ175 KI mice at the age of 12 months. Western blot analysis of total striatal extracts showed that Drp1 oligomers were significantly increased in zQ175 KI mice treated with control peptide TAT, indicative of Drp1 hyperactivation. In contrast, sustained treatment with P110 abolished Drp1 oligomerization (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. P110 treatment decreases Drp1 oligomerization in zQ175 KI mice.

zQ175 KI mice were treated with control peptide TAT or peptide P110 (3 mg/kg/day) starting from the age of 4 months. Total lysates of mouse striatum were harvested at the age of 12 months. Drp1 oligomerization was analyzed by western blot with anti-Drp1 antibodies in the absence or absence of β-ME. The quantitative histogram was determined by the relative density of Drp1 oligomer to total Drp1 protein. The data are mean ± SE, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test.

3.2. P110 treatment ameliorates behavior deficits in zQ175 KI mice

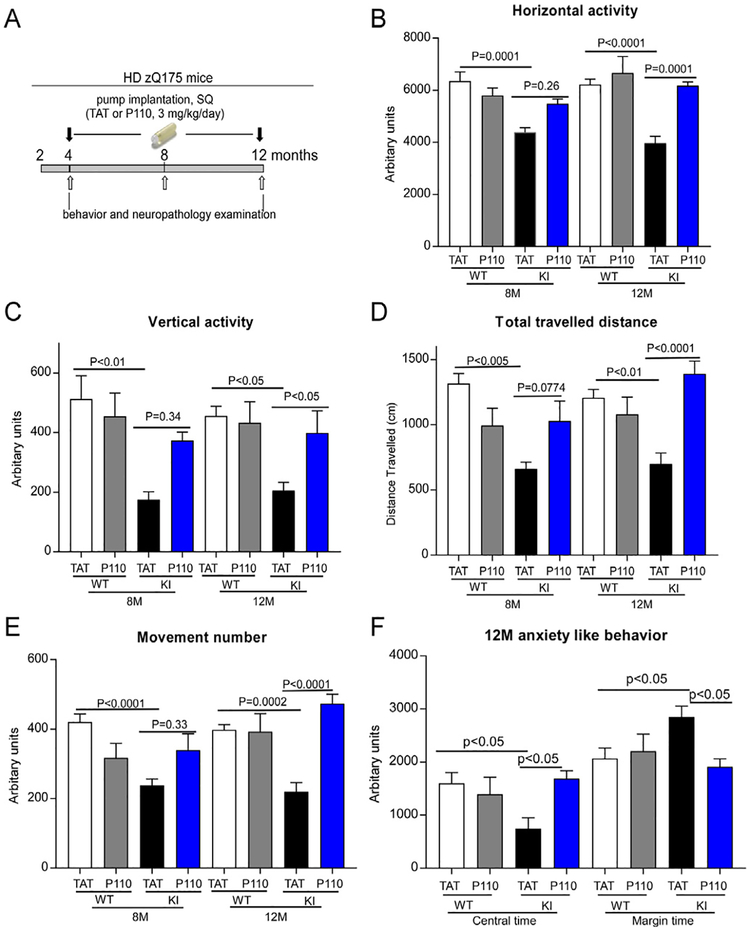

The zQ175 KI mice exhibit robust, progressive and early-onset disease phenotypes. Heterozygous zQ175 mice show an early presentation of the first signs of motor symptoms from 4 months of age, and behavioral deficits are accompanied with brain atrophy at 8 months of age [23]. To test whether P110 treatment attenuates the disease phenotypes in zQ175 KI mice, we subcutaneously treated zQ175 KI mice from the age of 4 monthse12 months with either control peptide TAT or peptide P110 (3 mg/kg/day). The treatment timeline is illustrated in Fig. 2A.

Fig. 2. P110 treatment reduces behavior deficits in zQ175 KI mice.

(A) The timeline of P110 treatment in zQ175 KI mice. Heterozygous zQ175 KI mice and wildtype littermates were treated with either the control peptide TAT or peptide P110 at 3 mg/kg/day from 4 to 12 months of age. (BeE) One hour of overall movement activity in zQ175 KI mice and wildtype littermates was determined by locomotion activity chamber at the age of 8 months and 12 months. Shown are horizontal activity (B), vertical activity(C), total travelled distance (D) and movement number (E). (F) Anxiety-like behavior of zQ175 KI mice was assessed at the age of 12 months by comparing the time that the mice spent in the central area versus the margin area in the open field chamber. All data are mean ± SEM, two-way ANOVA. n = 15–20 mice/group.

We found that zQ175 KI mice exhibited decreased locomotor activity starting from the age of 8 months, which was measured in the Open Field chambers. In contrast, treatment with P110 increased horizontal activity, vertical activity, movement number and total travelled distance of zQ175KI mice from the age of 8 months, and the treatment greatly reduced these behavioral deficits at the age of 12 months (Fig. 2B–E). Consistent with our previous studies [16,18], treatment with P110 had no significant effects on the behavioral status of wildtype mice through the study (Fig. 2).

In 8 month-old zQ175 KI mice, we found that the mice spent less time in the central zone of open field chambers but stayed for longer in the margin area. Such anxiety-like behavior in zQ175 KI mice became more severe at the age of 12 months (Fig. 2F). However, sustained treatment of P110 increased the time that the zQ175 KI mice spent in the central zone of open field chambers and decreased the time the mice explored in the margin area at the age of 12 months (Fig. 2F). The data suggest that P110 treatment reduces anxiety-like behavior of zQ175 KI mice.

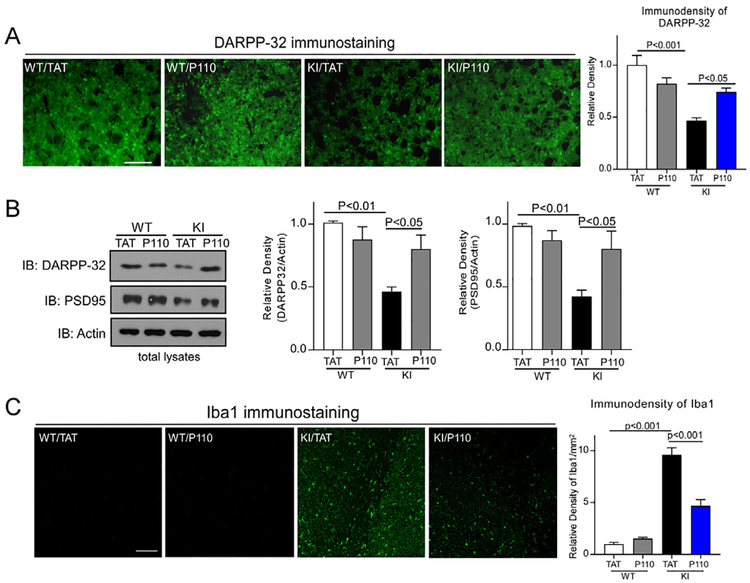

3.3. P110 treatment reduces neuropathology in zQ175 KI mice

DARPP-32 is a marker of medium spiny neurons, the decreased level of which is used as a marker of striatal neuronal survival in HD [24,25]. In 12 month-old zQ175 KI mice, we observed a significant decrease in the immune-density of DARPP-32 in the striatum, and P110 treatment improved the level of DARPP-32 (Fig. 3A). Consistently, western blot analysis of striatal extracts showed a reduction of DARPP-32 protein level in zQ175 KI mice at the age of 8 months, and treatment of P110 significantly increased the protein level of DARPP-32 (Fig. 3B). PSD95, a post-synaptic marker, maintains the postsynaptic density and is required for synapse plasticity [26]. We found that the PSD95 level was greatly decreased in zQ175 KI mouse striatum at age of 8 months, which was corrected by P110 treatment (Fig. 3B). In striatum of zQ175 KI mice, we also observed elevated immunodensity of Iba-1, which marks hyperactivated microglial cells. In contrast, treatment with P110 corrected this Iba1-labeled inflammatory response (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that P110 treatment improves striatal neuronal survival and reduces inflammatory response in vivo.

Fig. 3. P110 treatment reduces neuropathology in zQ175 KI mice.

Heterozygous zQ175 KI mice and wildtype littermates were treated with either the control peptide TAT or peptide P110 at 3 mg/kg/day from 4 to 12 months of age. (A) Representative images of DARPP-32 immunostaining in brain sections of zQ175 KI mice (12 months) at the indicated groups. Histogram: Quantitation of DARPP-32 immunodensity. Scale bar = 50 μm. Data are mean ± SE, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. (B) DARPP-32 and PSD95 protein levels were measured by western blot of mouse striatal lysates (8 months). Left: representative blots; Right: quantification on the relative density of DARPP-32 and PSD95 versus actin. Data are mean ± SE, n = 6 mice/group. (C) Representative images of Iba1 immunostaining in coronal brain sections of zQ175 KI mice (12 months). Scale bar = 50 μm. Histogram: The quantitation of Iba1 immuno-density/mm2. Data are mean ± SE, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. n = 6 mice/group.

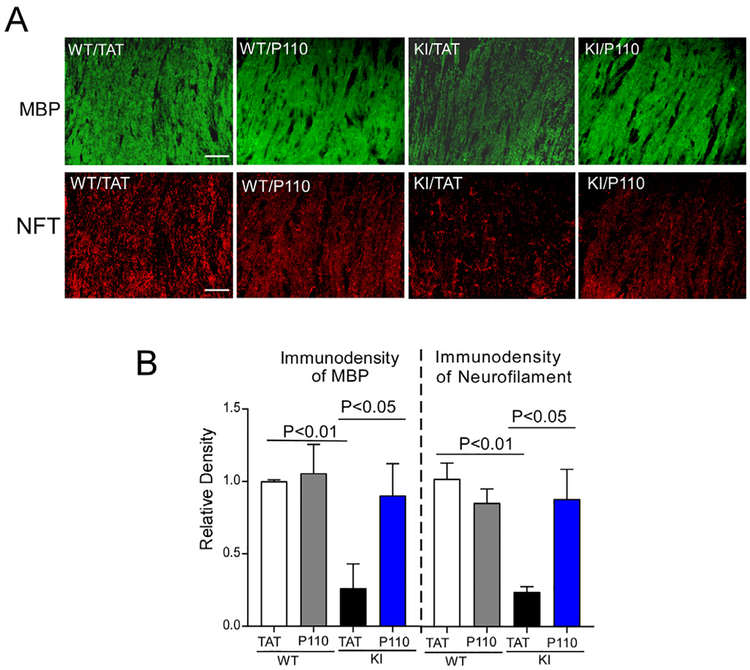

White matter (WM) atrophy is one of the pathological features in human HD [27–30]. Myelin basic protein (MBP) has been used as a marker to assess mature myelinating oligodendrocytes [31,32]. In 12 month-old zQ175 KI mice, we observed a dramatic decrease in MBP-immunopositive cells in the corpus callosum of zQ175 KI mice. P110 treatment attenuated this decrease (Fig. 4). Also, the zQ175 mice showed a decrease in immunodensity of neurofilament, a biomarker of HD [33,34], which was partially corrected after P110 treatment (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. P110 treatment reduces white matter disorganization in zQ175 KI mice.

Heterozygous zQ175 KI mice and wildtype littermates were treated with either the control peptide TAT or peptide P110 at 3 mg/kg/day from 4 to 12 months of age. (A) Representative images of MBP (upper) and neurofilament (lower) immunostaining in mouse brain sections containing corpus callosum (12 months), at the indicated groups. Scale bar = 30 μm. (B) Histogram: The quantitation on the immunodensity of MBP and neurofilament. Data are mean ± SE, n = 6 mice/group. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test.

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that inhibition of Drp1 hyper-activation through P110 peptide treatment reduces HD-associated neuropathology and behavioral deficits in the zQ175 KI mouse model. In particular, we found that: 1) Treatment with P110 inhibited Drp1 hyperactivation in zQ175 KI mice, as demonstrated by the treatment’s effect of abolishing Drp1 oligomerization; 2) Locomotor activity was impaired in zQ175 KI mice starting from the age of 8 months, and sustained treatment with P110 reduced these behavior deficits; 3) Neuropathological damage was elicited in zQ175 KI mice, as evidenced by medium spinal neuron loss, neuroinflammatory response and white matter disorganization. These pathologies were attenuated by P110 treatment.

Anxiety is one common feature in HD patients, which occurs years before the diagnosis of HD [35,36]. However, the mechanisms underlying anxiety-like behavior have not yet been described in detail. Mitochondrial dysfunction has been suggested to be an important factor in anxiety disorders [37,38]. Mitochondrial function in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) region of the brain is crucial for social behavior [39]. Highly anxious rats exhibit decreased mitochondrial function in the NAc region of the brain, providing insight into the potential treatment of anxiety disorders by targeting mitochondria. Treatment of P110 reduced the anxiety-like behavior in zQ175 KI mice, indicating that Drp1-induced mitochondrial abnormality contributes to anxiety disorders in HD. Inhibition of Drp1 S-palmitoylation due to a Zdhhc13 recessive mutation in mouse model causes motor deficits and anxiety-related behaviors [40]. This line of evidence also supports the hypothesis that Drp1 hyperactivation contributes to anxiety disorders accompanied by HD.

Brain atrophy, especially the preferential degeneration of the medium spiny neurons in the caudate of the striatum, has been considered as the major neuropathological hallmark in HD patients [24]. Besides this pattern, white matter atrophy and myelin breakdown are universal features of HD [41]. Mutant Htt reduces myelin gene expression and causes myelination deficient in HD [42]. Myelin that is produced by oligodendrocytes wraps the axon and maintains the axonal function. Our previous study demonstrated that inhibition of Drp1 hyperactivation through P110 treatment reduced the loss of the mature oligodendrocytes and repaired demyelination in Multiple Sclerosis (MS) [18]. In zQ175 KI HD mice, we also observed a decrease in myelin basic protein (MBP), which was corrected by P110 treatment. These findings from our previous and current studies suggest an important role of Drp1 activation in the regulation of myelination in oligodendrocytes, however a better understanding of the mechanistic details requires further investigation.

In summary, our study extends our previous findings in HD R6/2 mice [16] and demonstrates that inhibition of Drp1 hyperactivation by P110 treatment has a neuroprotective effect in zQ175 KI HD mice by attenuating behavioral deficits, striatal neuronal loss and white matter disorganization. Treatment with P110 also reduces anxiety-like behavior in zQ175 KI mice, suggesting that Drp1 hyper-activation is likely to be a target for mood disorders, which are common in many neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgment

This study is supported by National Institute Health (NIH) R01 NS088192 to X.Q.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors claim no financial conflict of interest.

References

- [1].A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington’s disease chromosomes. The Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group, Cell 72 (1993) 971–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Carmo C, Naia L, Lopes C, Rego AC, Mitochondrial dysfunction in Huntington’s disease, Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 1049 (2018) 59–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Detmer SA, Chan DC, Functions and dysfunctions of mitochondrial dynamics, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 8 (2007) 870–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chan DC, Mitochondria: dynamic organelles in disease, aging, and development, Cell 125 (2006) 1241–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Estaquier J, Arnoult D, Inhibiting Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission selectively prevents the release of cytochrome c during apoptosis, Cell Death Differ. 14 (2007) 1086–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cassidy-Stone A, Chipuk JE, Ingerman E, Song C, Yoo C, Kuwana T, Kurth MJ, Shaw JT, Hinshaw JE, Green DR, Nunnari J, Chemical inhibition of the mitochondrial division dynamin reveals its role in Bax/Bak-dependent mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, Dev. Cell 14 (2008) 193–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wang Z, Jiang H, Chen S, Du F, Wang X, The mitochondrial phosphatase PGAM5 functions at the convergence point of multiple necrotic death pathways, Cell 148 (2012) 228–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Guo X, Sesaki H, Qi X, Drp1 stabilizes p53 on the mitochondria to trigger necrosis under oxidative stress conditions in vitro and in vivo, Biochem. J 461 (2014) 137–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Su YC, Qi X, Inhibition of excessive mitochondrial fission reduced aberrant autophagy and neuronal damage caused by LRRK2 G2019S mutation, Hum. Mol. Genet 22 (2013) 4545–4561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zuo W, Zhang S, Xia CY, Guo XF, He WB, Chen NH, Mitochondria auto-phagy is induced after hypoxic/ischemic stress in a Drp1 dependent manner: the role of inhibition of Drp1 in ischemic brain damage, Neuropharmacology 86 (2014) 103–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Otera H, Wang CX, Cleland MM, Setoguchi K, Yokota S, Youle RJ,Mihara K, Mff is an essential factor for mitochondrial recruitment of Drp1 during mitochondrial fission in mammalian cells, JCB (J. Cell Biol.) 191 (2010) 1141–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhao J, Liu T, Jin SB, Wang XM, Qu MQ, Uhlen P, Tomilin N, Shupliakov O, Lendahl U, Nister M, Human MIEF1 recruits Drp1 to mitochondrial outer membranes and promotes mitochondrial fusion rather than fission, EMBO J. 30 (2011) 2762–2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lee YJ, Jeong SY, Karbowski M, Smith CL, Youle RJ, Roles of the mammalian mitochondrial fission and fusion mediators Fis1, Drp1, and Opa1 in apoptosis, Mol. Biol. Cell 15 (2004) 5001–5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Qi X, Qvit N, Su YC, Mochly-Rosen D, A novel Drp1 inhibitor diminishes aberrant mitochondrial fission and neurotoxicity, J. Cell Sci 126 (2013) 789–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Loson OC, Song Z, Chen H, Chan DC, Fis1, Mff, MiD49, and MiD51 mediate Drp1 recruitment in mitochondrial fission, Mol. Biol. Cell 24 (2013) 659–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Guo X, Disatnik MH, Monbureau M, Shamloo M, Mochly-Rosen D, Qi X, Inhibition of mitochondrial fragmentation diminishes Huntington’s disease-associated neurodegeneration, J. Clin. Invest 123 (2013) 5371–5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Filichia E, Hoffer B, Qi X, Luo Y, Inhibition of Drp1 mitochondrial trans-location provides neural protection in dopaminergic system in a Parkinson’s disease model induced by MPTP, Sci. Rep 6 (2016) 32656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Luo F, Herrup K, Qi X, Yang Y, Inhibition of Drp1 hyper-activation is protective in animal models of experimental multiple sclerosis, Exp. Neurol 292 (2017) 21–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Joshi AU, Saw NL, Vogel H, Cunnigham AD, Shamloo M, Mochly-Rosen D, Inhibition of Drp1/Fis1 interaction slows progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, EMBO Mol. Med 10 (2018) pii: e8166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Filichia E, Hoffer B, Qi X, Luo Y, Inhibition of Drp1 mitochondrial trans-location provides neural protection in dopaminergic system in a Parkinson’s disease model induced by MPTP, Sci. Rep. UK 6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Patel A, Siegel A, Zalcman SS, Lack of aggression and anxiolytic-like behavior in TNF receptor (TNF-R1 and TNF-R2) deficient mice, Brain Behav. Immun 24 (2010) 1276–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Otera H, Ishihara N, Mihara K, New insights into the function and regulation of mitochondrial fission, Bba Mol. Cell. Res 1833 (2013) 1256–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Heikkinen T, Lehtimaki K, Vartiainen N, Puolivali J, Hendricks SJ, Glaser JR,Bradaia A, Wadel K, Touller C, Kontkanen O, Yrjanheikki JM, Buisson B,Howland D, Beaumont V, Munoz-Sanjuan I, Park LC, Characterization of neurophysiological and behavioral changes, MRI brain volumetry and 1H MRS in zQ175 knock-in mouse model of Huntington’s disease, PLoS One 7 (2012), −50717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].van Dellen A, Welch J, Dixon RM, Cordery P, York D, Styles P, Blakemore C, Hannan AJ, N-Acetylaspartate and DARPP-32 levels decrease in the corpus striatum of Huntington’s disease mice, Neuroreport 11 (2000) 3751–3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bibb JA, Yan Z, Svenningsson P, Snyder GL, Pieribone VA, Horiuchi A, Nairn AC, Messer A, Greengard P, Severe deficiencies in dopamine signaling in presymptomatic Huntington’s disease mice, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 97 (2000) 6809–6814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fourie C, Kim E, Waldvogel H, Wong JM, McGregor A, Faull RL, Montgomery JM, Differential changes in postsynaptic density proteins in postmortem Huntington’s disease and Parkinson’s disease human brains, J. Neurodegener. Dis 2014 (2014) 938530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Phillips O, Squitieri F, Sanchez-Castaneda C, Elifani F, Caltagirone C,Sabatini U, Di Paola M, Deep white matter in Huntington’s disease, PLoS One 9 (2014), e109676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Jin J, Peng Q, Hou Z, Jiang M, Wang X, Langseth AJ, Tao M, Barker PB,Mori S, Bergles DE, Ross CA, Detloff PJ, Zhang J, Duan W, Early white matter abnormalities, progressive brain pathology and motor deficits in a novel knock-in mouse model of Huntington’s disease, Hum. Mol. Genet 24 (2015) 2508–2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Rosas HD, Lee SY, Bender AC, Zaleta AK, Vangel M, Yu P, Fischl B,Pappu V, Onorato C, Cha JH, Salat DH, Hersch SM, Altered white matter microstructure in the corpus callosum in Huntington’s disease: implications for cortical “disconnection”, Neuroimage 49 (2010) 2995–3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ciarmiello A, Cannella M, Lastoria S, Simonelli M, Frati L, Rubinsztein DC,Squitieri F, Brain white-matter volume loss and glucose hypometabolism precede the clinical symptoms of Huntington’s disease, J. Nucl. Med 47 (2006) 215–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Muller C, Bauer NM, Schafer I, White R, Making myelin basic protein - from mRNA transport to localized translation, Front. Cell. Neurosci 7 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Artemiadis AK, Anagnostouli MC, Apoptosis of oligodendrocytes and post-translational modifications of myelin basic protein in multiple sclerosis: possible role for the early stages of multiple sclerosis, Eur. Neurol 63 (2010) 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Soylu-Kucharz R, Sandelius A, Sjogren M, Blennow K, Wild EJ,Zetterberg H, Bjorkqvist M, Neurofilament light protein in CSF and blood is associated with neurodegeneration and disease severity in Huntington’s disease R6/2 mice, Sci. Rep. UK 7 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Byrne LM, Rodrigues FB, Blennow K, Neurofilament light protein in blood as a potential biomarker of neurodegeneration in Huntington’s disease: a retrospective cohort analysis (vol 16, pg 601, 2017), Lancet Neurol. 16 (2017), 683–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Dale M, van Duijn E, Anxiety in Huntington’s disease, J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci 27 (2015) 262–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Pla P, Orvoen S, Saudou F, David DJ, Humbert S, Mood disorders in Huntington’s disease: from behavior to cellular and molecular mechanisms, Front. Behav. Neurosci 8 (2014) 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hroudova J, Fisar Z, Raboch J, Mitochondrial Functions in Mood Disorders, 2013.

- [38].Burroughs S, French D, Depression and anxiety: role of mitochondria, Curr. Anaesth. Crit. Care 18 (2007) 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hollis F, van der Kooij MA, Zanoletti O, Lozano L, Canto C, Sandi C, Mitochondrial function in the brain links anxiety with social subordination, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112 (2015) 15486–15491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Napoli E, Song G, Liu S, Espejo A, Perez CJ, Benavides F, Giulivi C, Zdhhc13-dependent Drp1 S-palmitoylation impacts brain bioenergetics, anxiety, coordination and motor skills, Sci. Rep 7 (2017) 12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Tishler TA, Fong SM, Oluwadara B, Finn JP, Huang D,Bordelon Y, Mintz J, Perlman S, Myelin breakdown and iron changes in Huntington’s disease: pathogenesis and treatment implications, Neurochem. Res 32 (2007) 1655–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Huang B, Wei W, Wang G, Gaertig MA, Feng Y, Wang W, Li XJ, Li S, Mutant huntingtin downregulates myelin regulatory factor-mediated myelin gene expression and affects mature oligodendrocytes, Neuron 85 (2015) 1212–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]