Abstract

Logopenic primary progressive aphasia (lvPPA) typically results from underlying Alzheimer’s disease, but subjects have been reported that do not show beta-amyloid (Aβ) deposition. These subjects do not differ on neurological and speech-language testing from Aβ-positive lvPPA, but they impressionistically show increased grammatical deficits. We performed a quantitative linguistic analysis of grammatical characteristics in Aβ-negative lvPPA compared to Aβ-positive lvPPA and agrammatic PPA, which is characterized by increased grammatical difficulties. Aβ-negative lvPPA used fewer function words and correct verbs but more syntactic and semantic errors compared to Aβ-positive lvPPA. These measures did not differ between Aβ-negative lvPPA and agPPA. Both lvPPA cohorts showed a higher mean length of utterance, more complex sentences, and fewer nouns than agPPA. Aβ-negative lvPPA subjects appear unique and share linguistic features with both agPPA and Aβ-positive lvPPA. Quantitative language analysis in lvPPA may be able to distinguish those with and without Aβ deposition.

Keywords: Aphasia, logopenic, syntax, amyloid, PET, primary progressive aphasia, agrammatism

1.0. Introduction

Logopenic primary progressive aphasia (lvPPA) is a neurodegenerative language disorder that typically presents with language difficulties, including impaired single-word retrieval, difficulties repeating sentences, and phonological errors, which are believed to be caused by an impairment in the phonological loop of the verbal working memory (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2008; Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011; Henry & Gorno-Tempini, 2010; Whitwell, Duffy, et al., 2015).

These language difficulties differ from those found in agrammatic PPA (agPPA), which is characterized by agrammatic and telegraphic language production and grammatical simplification; more specifically, these language impairments include deficits with the production of inflectional morphology, lower proportion or complete omission of function words, higher proportion of nouns compared to other open class words, use of nonfinite (untensed) verb forms, syntactic argument structure errors, and overall reduced sentence and grammatical complexity (Ash et al., 2009; Avrutin, 2001; Grossman et al., 1996; C. K. Thompson, Ballard, Tait, Weintraub, & Mesulam, 1997; C. K. Thompson et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2010).

The majority of patients who are diagnosed with lvPPA have underlying Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology, showing beta-amyloid (Aβ) and tau deposition on PET imaging (M. Mesulam et al., 2008; Rabinovici et al., 2008; Whitwell, Jones, et al., 2015). Because of this, lvPPA is often considered an atypical AD variant. However, some patients do not show Aβ deposition on PET scanning and are thus believed to have underlying frontotemporal lobar degeneration, likely with TDP-43 pathology, (Josephs et al., 2014; Matías-Guiu et al., 2015; M. M. Mesulam et al., 2014; Santos-Santos et al., 2018; Spinelli et al., 2017; Whitwell, Jones, et al., 2015).

Imaging differences have been reported between lvPPA patients who differ in the presence versus absence of Aβ deposition: Aβ -positive lvPPA show increased grey matter atrophy in the right hemisphere, while the volume loss in Aβ -negative lvPPA is more localized in the left temporal region (Whitwell, Duffy, et al., 2015). Despite these structural differences, very few differences exist between lvPPA subjects who are Aβ-positive versus those who are Aβ-negative on neurological and speech-language testing (Whitwell, Jones, et al., 2015). However, a previous case report observed grammatical deficits in one Aβ-negative lvPPA patient that were uncharacteristic of typical lvPPA language difficulties (Rohrer, Crutch, Warrington, & Warren, 2010). To further investigate this finding of different language impairments in Aβ-negative lvPPA, we performed a quantitative analysis of the grammatical characteristics of Aβ-negative lvPPA subjects to determine whether their linguistic properties differ from those of Aβ-positive lvPPA subjects and those of agrammatic PPA (agPPA) subjects, who characteristically have grammatical difficulties.

A cohort of 50 lvPPA subjects underwent neurological and speech-language assessments, as well as Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) PET imaging to assess Aβ deposition. Six of these subjects were classified as Aβ-negative, as previously described (Whitwell, Jones, et al., 2015). The neurological, speech-language, genetic, and imaging findings have been previously reported for these six patients (Josephs et al., 2014; Whitwell, Jones, et al., 2015). These six subjects were compared to 15 Aβ-positive lvPPA and 15 agPPA participants, who were matched by age, gender, and Western Aphasia Battery Aphasia Quotient (WAB-AQ) score (Kertesz, 2007). The picture description task of the WAB was video recorded, and these speech samples were transcribed and coded for quantitative comparison between groups for syntactic structures and errors that have been shown to reveal agrammatic deficits; these included coding all grammatical categories, as well as semantic and syntactic errors, among other language variables (Ash et al., 2010; Tetzloff et al., 2018; Cynthia K Thompson & Mack, 2014). By quantifying their language production in this manner, we were able to compare the grammatical deficits of Aβ-negative lvPPA to their Aβ-positive lvPPA counterparts, as well as agPPA patients who are known to have syntactic deficits. We also assessed the patterns of grey matter atrophy in the Aβ-negative lvPPA, Aβ-positive lvPPA and agPPA subjects compared to controls to help us understand underlying neuroanatomical abnormalities.

2.0. Results

The three groups did not differ significantly in terms of age, gender, disease duration, education or WAB-AQ score (Table 1). No differences were observed between Aβ-negative and Aβ-positive lvPPA in neurological testing. The Aβ-negative group performed worse than agPPA on tests of verbal memory measured using the Auditory Verbal Learning Test, but did not differ from the Aβ-positive lvPPA group. However, all three groups performed comparably on testing of visual memory (Wechsler memory scale visual reproduction). The two lvPPA groups performed similarly on speech language testing, with Aβ-negative lvPPA showing worse sentence repetition than agPPA. Both lvPPA groups showed less Parkinsonism and apraxia of speech than the agPPA subjects. The neurological, neuropsychological and speech/language results of each individual Aβ-negative lvPPA subjects have been previously published (Josephs et al., 2014).

Table 1:

Demographics and clinical results

| Aβ(−) lvPPA n=6 | Aβ(+) lvPPA n=15 | agPPA n=15 | Aβ(−)~Aβ(+) FDR p-value | Aβ(−)~agPPA FDR p-value | Aβ(+)~agPPA FDR p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age at assessment, years | 66 (59.5, 68) | 66 (58.5 68) | 65 (59, 71.5) | 0.30 | 0.54 | 0.56 |

| Gender (%female) | 0.33 | 0.60 | 0.53 | 0.31 | 0.44 | 0.74 |

| Disease duration, years | 2 (2, 2.8) | 4 (3, 4.8) | 2.5 (2, 3.5) | 0.22 | 0.38 | 0.43 |

| Education | 17.5 (14.8, 18) | 16 (13, 17) | 13 (12, 16) | 0.96 | 0.50 | 0.67 |

| Age at onset, years | 63 (57.3, 65.8) | 62 (55, 64.5) | 60 (54.8, 69) | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0.94 |

| Neurological assessments | ||||||

| Mini-Mental Status Examination (/30) | 26.5 (25.3, 27.8) | 25 (23.5, 26.5) | 28 (25, 29) | 0.41 | 0.40 | <0.01* |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment Battery (/30) | 17 (14, 17.8) | 16 (14.5, 20.5) | 24 (22, 25.5) | 0.45 | 0.02* | 0.06 |

| Clinical Dementia rating sum of boxes (/18) | 2.5 (0.5 3.8) | 3.5 (1.8, 5) | 0.5 (0, 1.8) | 0.99 | 0.40 | 0.63 |

| Frontal Assessment Battery (/18) | 10 (6.5, 13.5) | 13 (11, 14.5) | 14 (12.5, 16) | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.48 |

| NPI-Q (/36) | 2 (1.3, 1.8) | 3 (1.5, 4) | 2 (1.5, 4) | 0.49 | 0.90 | 0.04* |

| WAB limb apraxia (/60) | 56.5 (54.5, 58.5) | 58 (56, 58) | 55 (51.5, 56) | 0.49 | 0.73 | 0.04* |

| MDS-UPDRS III (/132) | 6 (4, 8) | 4 (1, 6.5) | 10 (6, 20.3) | 0.52 | 0.04* | 0.62 |

| Neuropsychological assessments | ||||||

| Trail Making Test A MOANS | 9 (6.8, 9.8) | 6 (3.3, 9) | 7 (4.5, 9.5) | 0.71 | 1.00 | 0.81 |

| Trail Making Test B MOANS | 6.0 (2.0, 7.0) | 6.5 (3.3, 7.7) | 6.0 (4.0, 7.0) | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.88 |

| DKEFS card sort scaled score | 5 (1.8,6) | 7.5 (4, 8) | 8 (5, 9) | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.18 |

| WMS III VR % retention scaled score | 9.5 (8, 12.5) | 10 (7, 11.5) | 12 (9.5, 13) | 0.66 | 0.21 | 0.12 |

| AVLT Trial 5 raw | 3.5 (2.3, 4.8) | 6.5 (2.3, 8) | 9 (6.5, 10.5) | 0.50 | 0.03* | 0.23 |

| AVLT long-delay % retention MOANS | 5 (3.5, 5.8) | 5.5 (3.5, 7.8) | 8 (7, 9.5) | 0.70 | 0.03* | 0.23 |

| AVLT total learning trials 1 – 5 | 12.5 (12, 17.5) | 25 (18.5, 29) | 32 (26.5, 34.5) | 0.40 | 0.02* | 0.23 |

| VOSP letters | 19 (18, 20) | 19 (19, 20) | 20 (19, 20) | 0.88 | 0.34 | 0.19 |

| VOSP cubes | 10 (9.3, 10) | 9 (4.5, 10) | 9.5 (8.3, 10) | 0.87 | 0.38 | 0.12 |

| Speech and language assessments | ||||||

| Token Test (/22) | 9 (7, 13) | 14 (9, 16) | 14 (8.5, 17.5) | 0.85 | 0.38 | 0.51 |

| WAB aphasia quotient (/100) | 82.3 (75.6, 88.7) | 85.2 (83, 88.8) | 84.9 (79.7, 87.4) | 0.41 | 0.76 | 0.40 |

| WAB information content (/10) | 8 (8, 8) | 9 (8, 10) | 9 (8, 10) | 0.41 | 0.67 | 0.25 |

| WAB fluency (/10) | 8 (6, 9) | 8 (8, 9) | 6 (5.5, 9) | 0.90 | 0.23 | 0.13 |

| WAB repetition (/10) | 7.5 (6.8, 8.1) | 8 (7, 8.4) | 8.8 (8.4, 9.1) | 0.71 | 0.16 | 0.07 |

| WAB repetition items 10–15 (/66) | 37 (32.5, 44.5) | 46 (37, 50.5) | 52 (49, 56) | 0.44 | 0.04 | 0.22 |

| Boston Naming Test (/15) | 11 (4.3, 11.8) | 8 (5.5, 11.5) | 13 (11, 14) | 0.68 | 0.47 | <0.01* |

| Action fluency | 6 (4.3, 8.5) | 8 (5, 9.5) | 10 (7, 12) | 0.84 | 0.61 | 0.35 |

| Pyramids and Palm Trees (/52) | 47 (45.3, 50.3) | 49 (46.5, 50) | 49 (47.3, 50.8) | 0.90 | 0.47 | 0.47 |

| Apraxia of Speech Rating Scale (/64) | 1.5 (0.3, 3.5) | 2 (1, 3.5) | 21 (7, 25) | 0.98 | <0.01* | <0.01* |

Data are shown as Median (IQR). Values significant after FDR correction are marked with an asterisk.

NPI-Q = Neuropsychiatric Inventory brief questionnaire version; WAB = Western Aphasia Battery; MDS-UPDRS III = Movement Disorders Society sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; MOANS = Mayo Older American Normative Studies; DKEFs = Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System; WMS-III VR % retention = Wechsler memory scale visual reproduction, percent retention; AVLT = Auditory Verbal Learning Test; VOSP = Visual Object and Space Perception Battery

The MOANS, WMS-III VR % scaled score and DKEFS Card Sort are constructed to have a mean of 10 and standard deviation of 3 in cognitively healthy participants

Upon analyzing the speech samples, Aβ-negative lvPPA used a smaller proportion of verbs and function words (e.g., determiners, prepositions, etc.), had significantly fewer verbs that were produced with correct morphology, showed fewer utterances that were grammatical and more utterances that lacked a finite (tensed) verb form, and produced more syntactic and semantic errors than Aβ-positive lvPPA subjects (Table 2). These measures did not differ between c lvPPA and agPPA.

Table 2:

Linguistic results

| Grammatical/language measures | Aβ(−) lvPPA n=6 | Aβ(+) lvPPA n=15 | agPPA n=15 |

Aβ(−)~Aβ(+) FDR p-value | Aβ(−)~agPPA FDR p-value | Aβ(+)~agPPA FDR p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Utterances | 10.5 (8, 13) | 11 (8, 12.5) | 9 (7, 13.5) | 0.842 | 0.937 | 0.933 |

| Mean length of utterance (MLU) | 12.26 (7.58, 15.00) | 12.09 (10.60, 13.21) | 7.00 (4.82, 8.44) | 0.970 | 0.036* | <0.0001* |

| Word count | 94.5 (68, 118.75) | 112 (79.5, 118.5) | 57 (34, 88) | 0.622 | 0.173 | 0.006* |

| Ratio of Verbs: total words | 0.15 (0.13, 0.16) | 0.17 (0.16, 0.19) | 0.15 (0.14, 0.17) | 0.047* | 0.791 | 0.021* |

| Ratio of Nouns: total words | 0.21 (0.20, 0.23) | 0.22 (0.19, 0.25) | 0.32 (0.29, 0.41) | 0.791 | 0.001 | <0.0001* |

| Ratio Function words: total words | 0.37 (0.34, 0.38) | 0.47 (0.43, 0.52) | 0.44 (0.37, 0.47) | 0.005* | 0.213 | 0.245 |

| Ratio of Correct verbs: total verbs | 0.87 (0.85, 0.887) | 1 (1, 1) | 0.83 (0.44, 0.92) | <0.001* | 0.413 | <0.0001* |

| Ratio of Grammatical utterances: total utterances | 0.44 (0.33, 0.53) | 0.89 (0.74, 0.92) | 0.36 (0.21, 0.56) | 0.002* | 0.559 | <0.0001* |

| Ratio of Ungrammatical utterances: total utterances | 0.42 (0.21, 0.49) | 0.09 (0.04, 0.22) | 0.50 (0.26, 0.66) | 0.050 | 0.436 | <0.001* |

| Ratio of Non-utterances: total utterances | 0.10 (0.02, 0.26) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.14 (0, 0.30) | 0.004* | 0.968 | 0.002* |

| Ratio of Complex utterances: total utterances | 0.14 (0.03, 0.56) | 0.15 (0.10, 0.38) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.969 | 0.013 | <0.001* |

| Ratio of Semantic errors: total words | 0.04 (0.02, 0.06) | 0.01 (0, 0.02) | 0.02 (0, 0.05) | 0.008* | 0.411 | 0.090 |

| Ratio of Syntactic errors: total words | 0.02 (0.01, 0.04) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.06) | 0.005* | 0.459 | <0.0001* |

Data are shown as Median (IQR). Values significant after FDR correction are marked with an asterisk.

Both Aβ-negative and Aβ-positive lvPPA subjects showed a higher mean length of utterance (MLU), a greater proportion of complex utterances, and a smaller proportion of nouns than agPPA subjects (Table 2). Sample transcriptions from each participant group can be found in the Supplementary Material. Additionally, the grammatical results of each individual Aβ-negative lvPPA subject are shown in Table 3.

Table 3:

Individual linguistic results for the six Aβ-negative lvPPA subjects

| Grammatical/language measures | Subject 1 | Subject 2 | Subject 3 | Subject 4 | Subject 5 | Subject 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Utterances | 13 | 8 | 13 | 13 | 5 | 8 |

| Mean length of utterance (MLU) | 11.39 | 15.63 | 18.54 | 6.31 | 5.2 | 13.13 |

| Word count | 123 | 106 | 213 | 63 | 24 | 83 |

| Ratio of Verbs: total words | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.22 |

| Ratio of Nouns: total words | 0.2 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| Ratio Function words: total words | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| Ratio of Correct verbs: total verbs | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.96 | 0.83 |

| Ratio of Grammatical utterances: total utterances | 0.31 | 0.5 | 0.54 | 0.77 | 0.2 | 0.38 |

| Ratio of Ungrammatical utterances: total utterances | 0.38 | 0.5 | 0.46 | 0.15 | 0 | 0.8 |

| Ratio of Non-utterances: total utterances | 0.31 | 0 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.8 | 0.13 |

| Ratio of Complex utterances: total utterances | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.69 | 0 | 0 | 0.75 |

| Ratio of Semantic errors: total words | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| Ratio of Syntactic errors: total words | 0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

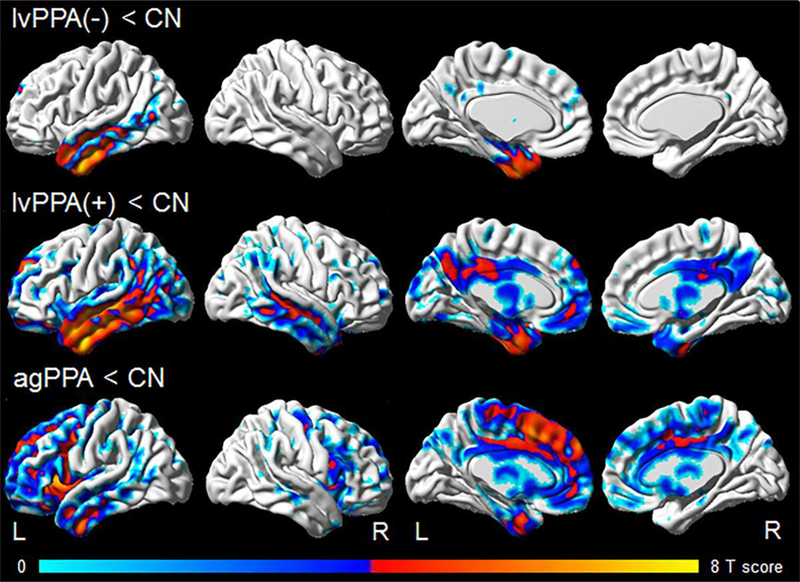

Both lvPPA groups showed grey matter loss in the temporoparietal lobes compared to controls, although the Aβ-negative subjects showed loss restricted to the left hemisphere and predominantly involved anterior regions of the temporal lobes (Figure 1). The agPPA group showed grey matter loss bilaterally in the frontal lobes, although with greater involvement of the left hemisphere, and particularly targeted inferior frontal and medial frontal regions, with some additional loss observed in the left temporoparietal lobe. The Aβ-negative lvPPA group did not differ from the other groups after correction for multiple comparisons. However, when assessed uncorrected at p<0.001, they showed smaller volumes in left anterior temporal lobe, but greater volumes in bilateral frontal regions, including the inferior frontal gyrus, compared to agPPA, and greater volumes in scattered regions in the right hemisphere compared to Aβ-positive lvPPA.

Figure 1: Patterns of grey matter loss in Aβ-negative lvPPA, Aβ-positive lvPPA and agPPA compared to controls.

Results are shown on three dimensional brain renderings using BrainNet Viewer (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/bnv/), with results shown corrected for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate correction at p<0.01.

3.0. Discussion

Despite a common diagnosis of aphasia, the presence versus absence of Aβ deposition may influence the speech characteristics of lvPPA. In our original description, Aβ-negative lvPPA subjects were not clinically judged to have agrammatism, because their speech output was not what is typically observed in agPPA (e.g., function word omission, subject-object reversal) (Josephs et al., 2014). However, the present quantitative language analysis revealed inadequacies in these subjects that their Aβ-positive lvPPA counterparts lacked. These included reduced production of function words and correct verbs, more syntactic and semantic errors, and a greater proportion of non-utterances. Aβ-negative lvPPA did not differ from agPPA on these measures. However, both lvPPA groups produced longer utterances, lower proportion of nouns, and more syntactically complex utterances than agPPA, demonstrating better overall syntactic performance in lvPPA, regardless of Aβ status. Aβ-negative lvPPA subjects, therefore, appear to have a unique linguistic profile, sharing grammatical features with both agPPA and lvPPA.

On neuroimaging, the patterns of grey matter loss in the Aβ-negative lvPPA group were more typical of lvPPA, with both lvPPA groups showing predominant involvement of the temporoparietal lobes; likely underpinning their deficits in naming and sentence repetition. The agPPA group showed more striking involvement of the frontal lobe, particularly the inferior frontal gyrus, as others have previously found (Botha et al., 2015; Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004; Josephs et al., 2006; M. Mesulam et al., 2008). The fact that damage to Broca’s area was not observed in Aβ-negative lvPPA, as previously shown in detail (Whitwell, Jones, et al., 2015), could support a view that the linguistic abnormalities observed in this cohort are fundamentally different, with a different underlying etiology, to those observed in agPPA. It is possible that areas of the language network, aside from Broca’s area, may be responsible for the linguistic abnormalities observed in Aβ-negative lvPPA (Grossman et al., 2013). Sentence production is indeed supported not only by Broca’s area but also regions in the temporal and parietal lobes. A functional MRI study that assessed brain regions involved in a picture description task showed that missing verbs, reduced sentence complexity and omission of function words were associated with changes in activation of the left posterior middle temporal gyrus and inferior parietal lobe, with the inferior frontal gyrus also involved in omission of function words (Schonberger et al., 2014). One structural difference between the lvPPA groups was that the Aβ-negative lvPPA subjects have significantly more grey matter atrophy in the left hemisphere than the right hemisphere, whereas Aβ-positive lvPPA show more bilateral patterns of degeneration (Whitwell, Duffy, et al., 2015). It is, therefore, possible that asymmetry of temporoparietal neurodegeneration could play a role in syntactic performance in Aβ-negative subjects.

Additionally, we previously showed that Aβ-negative lvPPA shows more hypometabolism on [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose PET in anteromedial temporal regions compared to Aβ-positive lvPPA (Whitwell, Jones, et al., 2015). This could further explain the higher proportion of semantic errors and the general decreased syntactic performance in Aβ-negative subjects, as these regions compose part of the language network (Papathanassiou et al., 2000; Stowe, Haverkort, & Zwarts, 2005).

The implications of our findings to the diagnostic classification of our subjects deserve some discussion, as the presence of agrammatism is one of three exclusionary features for lvPPA (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011). In regards to the consensus criteria for lvPPA, all of the Aβ-negative lvPPA subjects had a hesitant speech with word retrieval problems, all performed poorly on sentence repetition, and all performed poorly on tests of naming except for one, as previously published (Josephs et al., 2014). All but one subject had phonologic errors, all but one had spared word and object knowledge, and all had spared motor speech. Four of the subjects would meet criteria for lvPPA regardless of whether agrammatism was present or not, and two subjects would only meet criteria for lvPPA if agrammatism was absent. The linguistic analysis presented in this manuscript clearly illustrates that the speech output of the Aβ-negative subjects is abnormal and different from the Aβ-positive subjects, but whether these subjects should be labelled as agrammatic could be debated. On-one-hand, the Aβ-negative subjects performed poorly on a number of the linguistic metrics that typically characterize agPPA. However, on the other hand, the speech samples from these subjects look qualitatively different from those produced by agPPA subjects (Josephs et al., 2014), as they produce longer utterances, lower proportion of nouns, and more syntactically complex utterances than agPPA, and they show no evidence for abnormalities in Broca’s area on neuroimaging. Given these arguments, it is unclear whether the Aβ-negative lvPPA subjects should be considered to be agrammatic and hence a mixed variant of PPA (M. M. Mesulam et al., 2014; Spinelli et al., 2017), or whether they should be considered a distinct (Rohrer et al., 2010) or unclassifiable variant of PPA.

Both of the lvPPA groups were impaired on testing for verbal memory, although the Aβ-negative subjects performed worse. However, both lvPPA groups performed normally on a measure of visual memory suggesting they do have relatively preserved episodic memory, consistent with a root diagnosis of PPA. The diminished verbal memory in these groups is likely due at least in part to disruption of language function rather than a primary memory disorder affecting episodic memory more globally. Furthermore, none of the lvPPA subjects presented with complaints of memory loss, and in all subjects it was the language impairment that was affecting activities in daily living.

It is clear that the presence versus absence of Aβ deposition in lvPPA subjects corresponds to decreased syntactic performance in speech. These results suggest that quantitative assessment of language production in lvPPA may help identify Aβ-negative subjects in the absence of PET imaging. Identifying Aβ-negative cases would be particularly important to guide potential treatment strategies and to provide prognostic information for the patients.

4.0. Methods

All subjects were recruited from the Mayo Clinic, Department of Neurology, into an NIH-funded study investigating speech and language disorders. Each subject underwent a thorough speechlanguage evaluation by a speech language pathologist, and clinical diagnoses of lvPPA or agPPA were rendered by consensus after reviewing the clinical scores and video recordings of each subject, as previously described (Botha et al., 2015; Josephs et al., 2012). As part of the speech language battery, all subjects underwent testing with the WAB (Kertesz, 2007), and a total aphasia quotient (WAB-AQ) was calculated to provide a measure of overall aphasia severity. All subjects underwent a detailed neurological and neuropsychological battery, as previously published (Josephs et al., 2012). All subjects also underwent a Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) PET scan to assess amyloid deposition and a 3 Tesla volumetric head MRI that included a magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence with voxel dimensions of 1.2 × 1.0 × 1.0mm. A global PiB standard uptake value ratio was calculated for each subjects and of the 50 lvPPA subjects, six were found to be amyloid-negative based on a cut-point of 1.5, as previously described (Josephs et al., 2014; Whitwell, Jones, et al., 2015). These six subjects were then compared to 15 amyloid-positive lvPPA and 15 agPPA subjects for this study, who were matched by age, gender, and WAB-AQ score.

As part of the WAB, subjects were asked to describe a picture of a picnic scene and speak in sentences. The language samples were transcribed and coded in CHAT transcription format for use in the Computerized Language Analysis software (CLAN) (MacWhinney, 2000) by KAT. The transcriptions included word-level codes for various grammatical categories including nouns, verbs, and function words (e.g., articles, prepositions, pronouns, and other closed-class words), in addition to inflectional and derivational morphemes. Semantic errors, including incorrect words and non-specific word substitutes, such as using “thing” or “stuff” instead of the specific noun were marked. Syntactic errors were also coded, which included incorrect verbal morphology, non-finite (untensed) verb forms, and argument structure errors. Utterances were given an additional code of grammatical (0 errors), ungrammatical (≥1 error), or non-utterance (no finite/tensed verb). The number of utterances and words; mean length of utterance (MLU), which is the average number of morphemes per sentence; verb, noun, and function word counts; number of semantic and syntactic errors, number of complex utterances, and number of each utterance type were calculated using Computerized Language Analysis (MacWhinney, 2000). These variables, which reveal syntactic and agrammatic deficits (Ash et al., 2010; Cynthia K Thompson & Mack, 2014), were calculated as ratios to account for differences in number of utterances and words produced across speakers. Variables were compared between groups using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, and p-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using false discovery rate (FDR) correction in RStudio (RStudio, 2015).

Patterns of grey matter atrophy were assessed in the three subject groups (lvPPA(−), lvPPA(+) and agPPA) compared to a group of 15 healthy controls that underwent an identical MRI protocol (median [IQR] age at MRI = 56 [59–64], 67% female). All MPRAGE scans were spatially normalized to the Mayo Clinic Adult Lifespan Template (MCALT) (https://www.nitrc.org/projects/mcalt/) and segmented using the unified segmentation model (Ashburner & Friston, 2005) in SPM12 with MCALT tissue priors. The custom template space grey matter segmentations were modulated and smoothed at 8 mm full width at half maximum. Voxel-level comparisons were performed using two-sided T-tests in SPM, with results assessed at p<0.01 after correction for multiple comparisons using false discovery rate correction. Age and gender were included in the analysis as covariates.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Amyloid-negative lvPPA subjects have a unique linguistic profile.

Amyloid-negative lvPPA has some language features similar to amyloid-positive.

Amyloid-negative lvPPA also shares language features with agrammatic PPA.

The speech of lvPPA can help distinguish amyloid-negative versus -positive subjects.

Statement of significance:

We found a relationship between the presence versus absence of beta-amyloid deposition and impaired syntactic performance in a group of lvPPA subjects.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Clifford Jack for allowing the use of his laboratory resources, Matthew Senjem and Dr. Christopher Schwarz for writing the software code for the neuroimaging analysis, and Stephen D. Weigand for statistical advice.

Funding:

The study was supported by NIH grants R01 DC12519, R01 DC010367, R01 AG50603, R01 NS89757 and R21 NS94684.

Footnotes

Author disclosures:

Katerina Tetzloff receives research support from the National Science Foundation.

Dr. Whitwell receives research support from the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Utianski receives research support from the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Duffy receives research support from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Clark receives research support from the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Machulda receives research support from the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Strand has no disclosures.

Dr. Josephs receives research support from the National Institutes of Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ash S, McMillan C, Gunawardena D, Avants B, Morgan B, Khan A, . . . Grossman M(2010). Speech errors in progressive non-fluent aphasia. Brain and language, 113(1), 13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash S, Moore P, Vesely L, Gunawardena D, McMillan C, Anderson C, . . . Grossman M (2009). Non-fluent speech in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 22(4), 370–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J, & Friston KJ (2005). Unified segmentation. Neuroimage, 26(3), 839–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avrutin S (2001). Linguistics and agrammatism. Glot International, 5(3), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Botha H, Duffy JR, Whitwell JL, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Schwarz CG, . . . Josephs KA (2015). Classification and clinicoradiologic features of primary progressive aphasia (PPA) and apraxia of speech. Cortex, 69, 220–236. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2015.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorno-Tempini ML, Brambati S, Ginex V, Ogar J, Dronkers N, Marcone A, . . . Miller B (2008). The logopenic/phonological variant of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology, 71(16), 1227–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, . . . Grossman M (2011). Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology, 76(11), 1006–1014. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorno-Tempini ML, Dronkers NF, Rankin KP, Ogar JM, Phengrasamy L, Rosen HJ, . . . Miller BL (2004). Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Annals of neurology, 55(3), 335–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M, Mickanin J, Onishi K, Hughes E, D’Esposito M, Ding XS, . . . Reivich M (1996). Progressive Nonfluent Aphasia: Language, Cognitive, and PET Measures Contrasted with Probable Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 8(2), 135–154. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1996.8.2.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M, Powers J, Ash S, McMillan C, Burkholder L, Irwin D, & Trojanowski JQ (2013). Disruption of large-scale neural networks in non-fluent/agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasia associated with frontotemporal degeneration pathology. Brain Lang, 127(2), 106–120. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry ML, & Gorno-Tempini ML (2010). The logopenic variant of primary progressive aphasia. Current opinion in neurology, 23(6), 633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Master AV, . . . Whitwell JL (2012). Characterizing a neurodegenerative syndrome: primary progressive apraxia of speech. Brain, 135(Pt 5), 1522–1536. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Vemuri P, Senjem ML, . . . Whitwell JL (2014). Progranulin-associated PiB-negative logopenic primary progressive aphasia. J Neurol, 261(3), 604–614. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7243-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Whitwell JL, Layton KF, Parisi JE, . . . Petersen RC (2006). Clinicopathological and imaging correlates of progressive aphasia and apraxia of speech. Brain, 129(Pt 6), 1385–1398. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz A (2007). Western Aphasia Battery (Revised) PsychCorp; San Antonio. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney B (2000). The CHILDES project: The database (Vol. 2): Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matías-Guiu JA, Cabrera-Martín MN, Moreno-Ramos T, Valles-Salgado M, Fernandez-Matarrubia M, Carreras JL, & Matías-Guiu J (2015). Amyloid and FDG-PET study of logopenic primary progressive aphasia: evidence for the existence of two subtypes. Journal of neurology, 262(6), 1463–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M, Wicklund A, Johnson N, Rogalski E, Léger GC, Rademaker A, . . . Bigio EH(2008). Alzheimer and frontotemporal pathology in subsets of primary progressive aphasia. Annals of neurology, 63(6), 709–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM, Weintraub S, Rogalski EJ, Wieneke C, Geula C, & Bigio EH (2014). Asymmetry and heterogeneity of Alzheimer’s and frontotemporal pathology in primary progressive aphasia. Brain, 137(Pt 4), 1176–1192. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papathanassiou D, Etard O, Mellet E, Zago L, Mazoyer B, & Tzourio-Mazoyer N (2000). A common language network for comprehension and production: a contribution to the definition of language epicenters with PET. Neuroimage, 11(4), 347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovici GD, Jagust WJ, Furst AJ, Ogar JM, Racine CA, Mormino EC, . . . Miller BL (2008). Aβ amyloid and glucose metabolism in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Annals of neurology, 64(4), 388–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer JD, Crutch SJ, Warrington EK, & Warren JD (2010). Progranulin-associated primary progressive aphasia: a distinct phenotype? Neuropsychologia, 48(1), 288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RStudio. (2015). RStudio: integrated development for R. RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Santos MA, Rabinovici GD, Iaccarino L, Ayakta N, Tammewar G, Lobach I, . . . Spinelli E(2018). Rates of amyloid imaging positivity in patients with primary progressive aphasia. JAMA neurology, 75(3), 342–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonberger E, Heim S, Meffert E, Pieperhoff P, da Costa Avelar P, Huber W, . . . Grande M (2014). The neural correlates of agrammatism: Evidence from aphasic and healthy speakers performing an overt picture description task. Front Psychol, 5, 246. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli EG, Mandelli ML, Miller ZA, Santos-Santos MA, Wilson SM, Agosta F, . . . Meyer M(2017). Typical and atypical pathology in primary progressive aphasia variants. Annals of neurology, 81(3), 430–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowe LA, Haverkort M, & Zwarts F (2005). Rethinking the neurological basis of language. Lingua, 115(7), 997–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Tetzloff KA, Utianski RL, Duffy JR, Clark HM, Strand EA, Josephs KA, & Whitwell JL (2018). Quantitative Analysis of Agrammatism in Agrammatic Primary Progressive Aphasia and Dominant Apraxia of Speech. J Speech Lang Hear Res, 1–10. doi: 10.1044/2018_JSLHR-L-17-0474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CK, Ballard KJ, Tait ME, Weintraub S, & Mesulam MM (1997). Patterns of language decline in non-fluent primary progressive aphasia. Aphasiology, 11(4–5), 297–321. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CK, Cho S, Hsu CJ, Wieneke C, Rademaker A, Weitner BB, . . . Weintraub S (2012). Dissociations Between Fluency And Agrammatism In Primary Progressive Aphasia. Aphasiology, 26(1), 20–43. doi: 10.1080/02687038.2011.584691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CK, & Mack JE (2014). Grammatical impairments in PPA. Aphasiology, 28(8–9), 1018–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitwell JL, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Schwarz CG, . . . Lowe VJ (2015). Clinical and neuroimaging biomarkers of amyloid-negative logopenic primary progressive aphasia. Brain and language, 142, 45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitwell JL, Jones DT, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Przybelski SA, . . . Senjem ML (2015). Working memory and language network dysfunctions in logopenic aphasia: a task-free fMRI comparison with Alzheimer’s dementia. Neurobiology of aging, 36(3), 1245–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SM, Dronkers NF, Ogar JM, Jang J, Growdon ME, Agosta F, . . . Gorno-Tempini ML (2010). Neural correlates of syntactic processing in the nonfluent variant of primary progressive aphasia. The Journal of Neuroscience, 30(50), 16845–16854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.