Abstract

Background: As online health information becomes common, it is important to assess patients' access to and experiences with online resources.

Introduction: We examined whether glaucoma patients' technology usage differs by medication adherence and whether adherence is associated with online education experiences.

Materials and Methods: We included 164 adults with glaucoma taking ≥1 glaucoma medication. Participants completed a survey including demographic and health information, the Morisky Adherence Scale, and questions about online glaucoma resource usage. Differences in technology access, adherence, and age were compared with chi-squared, Fisher exact, and two-sample t-tests.

Results: Mean age was 66 years. Twenty-six percent reported poor adherence. Eighty percent had good technology access. Seventy-three percent of subjects with greater technology access wanted online glaucoma information and yet only 14% of patients had been directed to online resources by physicians. There was no relationship between technological connectivity and adherence (p = 0.51). Nonadherent patients were younger (mean age 58 years vs. 66 years for adherent patients, p = 0.002). Nonadherence was associated with negative feelings about online searches (68% vs. 42%, p = 0.06).

Discussion: Younger, poorly adherent patients navigate online glaucoma resources without physician input. These online searches are often unsatisfying. Technology should be leveraged to create high quality, online glaucoma resources that physicians can recommend to provide guidance for disease self-management.

Keywords: glaucoma, medication adherence, e-health, education, self-management

Background

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness.1 Currently, there are ∼60 million glaucoma patients aged 40–80 years worldwide, and this number is expected to almost double to 110 million by 2040 due to rapidly aging populations.2 Multiple randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that medical treatments that decrease intraocular pressure preserve the visual field.3,4 However, only about 50% of glaucoma patients adhere to their treatment regimen.5 Such poor adherence is a major driver of glaucoma's status as a leading cause of preventable blindness.6–8

Introduction

Glaucoma is most prevalent in persons over the age of 65 years,9 an age group that has traditionally been less likely to access health education materials on the internet;10 however, between 2000 and 2014, the percent of American adults over the age of 65 who use the internet has risen from 14% to 58%.11 In a 2012 Pew Research Center survey, 72% of internet users reported searching online for health information during the previous year.10 Some studies have shown that glaucoma patients with access to the internet or a smart phone are receptive to receiving glaucoma-related e-mails or text messages, although such technologies have most often been used in the context of remembering to administer eye drops or attend doctor appointments.12,13 In contrast, other studies have shown that adults 65 years or older were less likely to trust the internet as a source of health information.14 Thus, while technological innovation can enhance communication with patients, it is important to consider patients' comfort with technology when developing interventions to improve glaucoma medication adherence.15

The objective of this study was to assess adult glaucoma patients' access to and experiences with e-health technologies. We also aimed to evaluate whether technology use differs by medication adherence status and whether technology use differs between older and younger glaucoma patients.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Sample Selection

This was a prospective survey study. We recruited a convenience sample of glaucoma patients from two glaucoma clinics by approaching all patients in the clinic waiting rooms once weekly between January and April 2013. One glaucoma clinic was at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and the other was at a private practice in Baltimore, Maryland. Eligibility criteria for study inclusion included taking ≥1 intraocular pressure lowering medication and age ≥18 years. Non-English speakers were excluded. Patients interested in participating were given a printed survey to complete in the waiting room or to take home and return by mail if they preferred. A trained research assistant was available to assist participants in answering the questionnaire in the waiting room.

Institutional Review Board

This study was approved prospectively as an exempt study by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (No. HUM00064465) because no personal health identifiers were collected. The study adhered to the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration.

Questionnaire

The printed questionnaire consisted of 33 questions and took ∼20 min to complete. The survey was written at an eighth-grade or lower reading level as determined by Fleish-Kincaid software in Microsoft Office. The survey included demographic and health information, the Morisky Adherence Scale,16 and questions about use of and attitudes toward online resources for glaucoma education. Demographic variables included age, gender, location, and level of education. Questions about disease characteristics included length of glaucoma diagnosis, number of glaucoma medications, number of chronic medical conditions, subjective overall health status, and eyesight status. Self-reported adherence to glaucoma medications was measured by the validated Morisky Medication Adherence Scale adapted for glaucoma. The Morisky scale has been used to measure adherence in a wide variety of chronic conditions, including glaucoma.17 Those deemed to be adherent scored 0 or 1 on the 8-question scale, while nonadherent patients scored ≥2.16,17 Questions about technology usage included access to internet at home, frequency and duration of internet use, cellphone usage, and use of technology or interest in utilizing technology to learn about glaucoma. The survey employed a skip pattern, so participants who reported using technology regularly were further surveyed to assess their use of and attitudes surrounding obtaining information about glaucoma online. Information on patients who declined to participate in the study was not collected.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were performed for the demographic and technology usage variables. We summarized participant characteristics using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. The questionnaire results were summarized with frequency distributions. We defined greater access to technology as answering “yes” to both computer and cellphone ownership and less access to technology as answering “no” to at least one question regarding computer and cellphone ownership. We defined “negative” emotions about online searches for glaucoma information as overwhelmed, confused, frustrated, and frightened. We defined “positive” emotions as eager, relieved or comforted, and confident. We tested for differences in descriptive statistics between patients with more and less access to technology, between adherent and nonadherent patients and between patients < and ≥70 years of age using chi-squared tests, two-sample t-tests, and Fisher exact tests. Although we report the number of missing responses, missing data were not included in our analyses. We used logistic regression to evaluate the relationship between adherence and access to technology among the older and younger cohorts (< and ≥70 years of age). SAS version 9.4 was used for all statistical analyses (SAS, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

The questionnaire response rate was 68%, with 273 questionnaires handed out and 185 returned. One hundred sixty-four out of 185 subjects (89%) provided complete information on their use of technology. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for patients who answered questions on technology usage. Overall, 117 patients (74%) were adherent to glaucoma medications. The population was 52% female, and the average age was 66 ± 14 years. Forty-two percent of patients were 70 years old or older. Highest educational level attained were fairly equally distributed between high school (31%), college (33%), and graduate school (33%). On average, patients documented having 2 ± 2 chronic medical conditions and most ranked their health as very good (35%) or good (39%). Subjects had a diagnosis of glaucoma for an average of 12 ± 11 years and the average number of glaucoma medications was 2 ± 1. While many subjects rated their eyesight as very good (25%) or good (38%), a significant minority rated their vision as fair (24%) or worse than fair (9%).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics by Access to Technology*

| VARIABLE | VALUE | LESS ACCESS TO TECHNOLOGY | GREATER ACCESS TO TECHNOLOGY | OVERALL | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, N (row %) | 33 (20.1) | 131 (79.9) | 164 | ||

| Site | Ann Arbor | 26 (78.8) | 74 (56.5) | 100 (61.0) | 0.02a |

| Baltimore | 7 (21.2) | 57 (43.5) | 64 (39.0) | ||

| Age (Nmiss = 2) | 75.3 ± 10.1; (58–95) | 63.6 ± 13.5; (26–93) | 66.0 ± 13.7; (26–95) | <0.0001b | |

| Gender (Nmiss = 2) | Female | 20 (60.6) | 64 (49.6) | 84 (51.9) | 0.26a |

| Male | 13 (39.4) | 65 (50.4) | 78 (48.1) | ||

| Adherent (Nmiss = 5) | No | 7 (21.9) | 35 (27.6) | 42 (26.4) | 0.51a |

| Yes | 25 (78.1) | 92 (72.4) | 117 (73.6) | ||

| Length of glaucoma diagnosis, years (Nmiss = 10) | 13.1 ± 14.5 (0.5–50) | 11.4 ± 10.2 (0.5–55) | 11.7 ± 11.2; (0.5–55) | 0.45b | |

| Number of glaucoma medications (Nmiss = 2) | 2.3 ± 1.3 (0–5) | 2.4 ± 1.2 (1–5) | 2.4 ± 1.2; (0–5) | 0.77b | |

| Number of chronic medical conditions (Nmiss = 8) | 2.4 ± 1.3 (1–7) | 2.2 ± 1.7 (0–9) | 2.3 ± 1.6; (0–9) | 0.56b | |

| Subjective overall health status (Nmiss = 3) | Excellent | 1 (3.1) | 22 (17.1) | 23 (14.3) | 0.13c |

| Very good | 10 (31.3) | 46 (35.7) | 56 (34.8) | ||

| Good | 16 (50.0) | 47 (36.4) | 63 (39.1) | ||

| Fair | 5 (15.6) | 14 (10.9) | 19 (11.8) | ||

| Poor | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Very poor | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Subjective eyesight status (Nmiss = 2) | Excellent | 1 (3.0) | 7 (5.4) | 8 (4.9) | 0.26c |

| Very good | 5 (15.2) | 35 (27.1) | 40 (24.7) | ||

| Good | 15 (45.5) | 46 (35.7) | 61 (37.7) | ||

| Fair | 7 (21.2) | 32 (24.8) | 39 (24.1) | ||

| Poor | 1 (3.0) | 5 (3.9) | 6 (3.7) | ||

| Very poor | 3 (9.1) | 3 (2.3) | 6 (3.7) | ||

| Completely blind | 1 (3.0) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.2) | ||

| Education level (Nmiss = 7) | <High school | 3 (10.0) | 1 (0.8) | 4 (2.5) | 0.001c |

| High school | 15 (50.0) | 34 (26.8) | 49 (31.2) | ||

| College | 8 (26.7) | 44 (34.6) | 52 (33.1) | ||

| Graduate degree | 4 (13.3) | 48 (37.8) | 52 (33.1) |

N (Column %) or Mean − St Dev (Range).

Chi-square test.

Two-sample t-test.

Fisher exact test.

A majority, 131 out of 164 participants (80%), had access to both computers and cellphones. Table 1 compares the demographics and disease characteristics between those who had greater and less access to technology. Those who had less access to technology were older (75 years vs. 64 years, p < 0.0001), more likely to have only completed grade school or high school (60% vs. 28%, p = 0.001), and to live in Ann Arbor compared to Baltimore (79% vs. 21%, p = 0.02). Of the patients with greater access to technology, 92 (72%) were adherent. Out of the patients with less access to technology, 25 (78%) were adherent. There was no significant difference between rates of adherence between those with greater and less access to technology (78% and 72% adherence respectively; p = 0.51).

Table 2 shows patterns of technology usage among patients with greater access to technology. The majority of those with greater access to technology used the internet daily (73%). Over half had used their cellphone to text/email (60%), though fewer (47%) had used their phone to access the internet. Most respondents with greater access to technology were interested in receiving information about glaucoma via e-mail or the internet (73%). Fewer, however, had actually used the internet to learn about glaucoma (62%), and fewer yet (14%) reported that their physician had ever recommended Web-based glaucoma resources to them (Fig. 1). Respondents most commonly endorsed using the internet to search for information about new doctors/hospitals/medical treatments (89%, n = 57), read or learn about other glaucoma patients' health experiences (55%, n = 36), keep track of personal health information (46%, n = 30), or communicate with a doctor or doctor's office (39%, n = 25). Approximately 84% (n = 53) of respondents felt the information they got from the internet about glaucoma was somewhat or very useful, while only 33% (n = 20) felt the internet was somewhat or very useful in obtaining encouragement or emotional support.

Table 2.

Age and Technology Usage of Patients with Greater Access to Technology*

| QUESTION | RESPONSES | NOT ADHERENT | ADHERENT | TOTAL | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, N (row %) | 35 (27.6) | 92 (72.4) | 127 | ||

| Age (Nmiss = 2) | 57.8 (15.3) | 66.2 (12.3) | 63.9 (13.6) | 0.002a | |

| Daily internet use (Nmiss = 3) | No | 12 (35.3) | 21 (23.3) | 33 (26.6) | 0.18b |

| Yes | 22 (64.7) | 69 (76.7) | 91 (73.4) | ||

| Do you send or receive email? (Nmiss = 5) | No | 4 (12.5) | 4 (4.4) | 8 (6.6) | 0.20c |

| Yes | 28 (87.5) | 86 (95.6) | 114 (93.4) | ||

| Uses cellphone to text/email (Nmiss = 2) | No | 10 (29.4) | 40 (44.0) | 50 (40.0) | 0.14b |

| Yes | 24 (70.6) | 51 (56.0) | 75 (60.0) | ||

| Uses cellphone to access the internet (Nmiss = 2) | No | 12 (34.3) | 54 (60.0) | 66 (52.8) | 0.001b |

| Yes | 23 (65.7) | 36 (40.0) | 59 (47.2) | ||

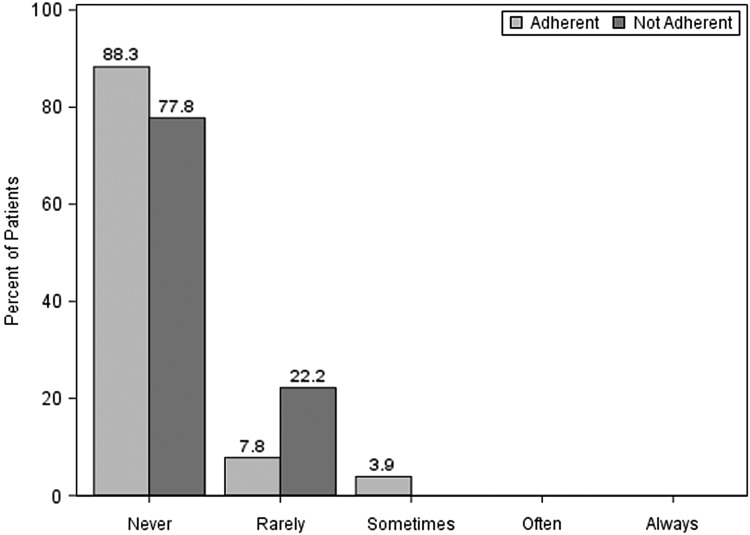

| When you see your doctor(s), how often do they recommend you visit a Website or online resource to find more information on glaucoma/treatments? (Nmiss = 23) | Never | 21 (77.8) | 68 (88.3) | 89 (85.6) | 0.12c |

| Rarely | 6 (22.2) | 6 (7.8) | 12 (11.5) | ||

| Sometimes | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.9) | 3 (2.9) | ||

| Often | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Always | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Would you like to get information about glaucoma/treatments by email or the internet? (Nmiss = 35) | No | 8 (29.6) | 17 (26.2) | 25 (27.2) | 0.73b |

| Yes | 19 (70.4) | 48 (73.8) | 67 (72.8) | ||

| Have you ever visited a Website to learn about glaucoma? (Nmiss = 34) | No | 12 (40.0) | 23 (36.5) | 35 (37.6) | 0.75b |

| Yes | 18 (60.0) | 40 (63.5) | 58 (62.4) | ||

| How useful was the information you got from the internet about glaucoma? (Nmiss = 64) | Not useful | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (1.6) | 0.11c |

| A little useful | 5 (25.0) | 4 (9.3) | 9 (14.3) | ||

| Somewhat useful | 7 (35.0) | 27 (62.8) | 34 (54.0) | ||

| Very useful | 8 (40.0) | 11 (25.6) | 19 (30.2) | ||

| Have you used the internet to do these things? (Yes/No) | |||||

| Read or learn about other patient's health experiences? (Nmiss = 61) | No | 8 (40.0) | 22 (47.8) | 30 (45.5) | 0.56b |

| Yes | 12 (60.0) | 24 (52.2) | 36 (54.5) | ||

| Searched for information about doctors, hospitals, or new medical treatments? (Nmiss = 63) | No | 0 (0.0) | 7 (15.2) | 7 (10.9) | 0.18c |

| Yes | 18 (100.0) | 39 (84.8) | 57 (89.1) | ||

| Communicate with a doctor or doctor's office? (Nmiss = 63) | No | 14 (73.7) | 25 (55.6) | 39 (60.9) | 0.17b |

| Yes | 5 (26.3) | 20 (44.4) | 25 (39.1) | ||

| Kept track of personal health information? (Nmiss = 62) | No | 12 (63.2) | 23 (50.0) | 35 (53.8) | 0.33b |

| Yes | 7 (36.8) | 23 (50.0) | 30 (46.2) | ||

| How useful was the internet in helping you get encouragement or emotional support? (Nmiss = 67) | Not useful | 10 (52.6) | 19 (46.3) | 29 (48.3) | 1.00c |

| A little useful | 3 (15.8) | 8 (19.5) | 11 (18.3) | ||

| Somewhat useful | 3 (15.8) | 8 (19.5) | 11 (18.3) | ||

| Very useful | 3 (15.8) | 6 (14.6) | 9 (15.0) | ||

| The LAST time you searched for information about glaucoma online, at any point did you feel: | |||||

| Overwhelmed (Nmiss = 63) | No | 14 (73.7) | 40 (88.9) | 54 (84.4) | 0.15c |

| Yes | 5 (26.3) | 5 (11.1) | 10 (15.6) | ||

| Eager (Nmiss = 64) | No | 10 (52.6) | 25 (56.8) | 35 (55.6) | 0.76b |

| Yes | 9 (47.4) | 19 (43.2) | 28 (44.4) | ||

| Confused (Nmiss = 63) | No | 12 (63.2) | 40 (88.9) | 52 (81.3) | 0.03c |

| Yes | 7 (36.8) | 5 (11.1) | 12 (18.8) | ||

| Relieved or Comforted (Nmiss = 64) | No | 13 (65.0) | 25 (58.1) | 38 (60.3) | 0.60b |

| Yes | 7 (35.0) | 18 (41.9) | 25 (39.7) | ||

| Frustrated (Nmiss = 64) | No | 14 (73.7) | 33 (75.0) | 47 (74.6) | 1.00c |

| Yes | 5 (26.3) | 11 (25.0) | 16 (25.4) | ||

| Confident (Nmiss = 64) | No | 7 (38.9) | 13 (28.9) | 20 (31.7) | 0.44b |

| Yes | 11 (61.1) | 32 (71.1) | 43 (68.3) | ||

| Frightened (Nmiss = 64) | No | 15 (78.9) | 38 (86.4) | 53 (84.1) | 0.47c |

| Yes | 4 (21.1) | 6 (13.6) | 10 (15.9) | ||

| Positive about the experience (Nmiss = 63) | No | 3 (15.8) | 8 (17.8) | 11 (17.2) | 1.00c |

| Yes | 16 (84.2) | 37 (82.2) | 53 (82.8) | ||

| Negative about the experience (Nmiss = 63) | No | 6 (31.6) | 26 (57.8) | 32 (50.0) | 0.06b |

| Yes | 13 (68.4) | 19 (42.2) | 32 (50.0) | ||

| Has anyone ever looked for information about glaucoma on the internet for you? (excluding healthcare providers) (Nmiss = 18) | No | 29 (96.7) | 62 (78.5) | 91 (83.5) | 0.02b |

| Yes | 1 (3.3) | 17 (21.5) | 18 (16.5) | ||

N (Column %) or Mean (SD)

Two-sample t-test.

Chi-square test.

Fisher exact test.

Fig. 1.

Responses to the survey question “How often does your doctor recommend an online glaucoma resource?”

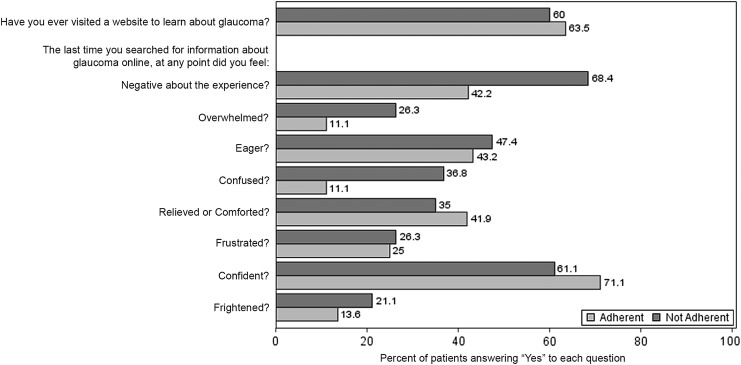

Among those with greater access to technology, we analyzed differences between patients who were adherent and nonadherent to their glaucoma medications (Table 2). Those who were adherent to their glaucoma medications were older (66 years vs. 58 years, p = 0.002) and less likely to use their cellphone to access the internet (40% vs. 66%, p = 0.001). Those who were nonadherent were more likely to be confused about information about glaucoma that they found online (37% vs. 11%, p = 0.03) and more likely to have felt negatively about their last online search for information about glaucoma (68% vs. 42%, p = 0.06) (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Study participants' use of the internet to learn about glaucoma and their emotional responses to their online searches.

Age impacted the way in which respondents used technology (Table 3). Patients 70 years and older were less likely to use their cellphones to e-mail, text, access the internet, download applications, or look for information about glaucoma (p < 0.05). Patients in this older age group were less likely to desire information about glaucoma via the internet or email (54% vs. 72%, p = 0.04) or via their cellphone (8% vs. 21%, p = 0.03). However, there was no association between greater access to technology and medication adherence in either age group. Having greater access to technology was not significantly associated with adherence among those <70 years of age (odds ratio [OR] = 0.76, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.19–3.10), p = 0.71) or among patients ≥70 years of age (OR = 1.18, 95% CI 0.30–4.58, p = 0.81).

Table 3.

| QUESTION | RESPONSES | <70 YEARS | ≥70 YEARS | TOTAL | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, N (row %) | 108 (58.1) | 78 (41.9) | 186 | ||

| Adherent (Nmiss = 5) | No | 32 (30.8) | 15 (19.5) | 47 (26.0) | 0.09a |

| Yes | 72 (69.2) | 62 (80.5) | 134 (74.0) | ||

| Do you have a computer or other means of accessing the internet? (Nmiss = 20) | No | 8 (7.9) | 10 (15.4) | 18 (10.8) | 0.13a |

| Yes | 93 (92.1) | 55 (84.6) | 148 (89.2) | ||

| Would you like to get information about glaucoma/treatments by email or the internet? (Nmiss = 59) | No | 22 (27.8) | 22 (45.8) | 44 (34.6) | 0.04a |

| Yes | 57 (72.2) | 26 (54.2) | 83 (65.4) | ||

| Would you like to get information about glaucoma/treatments sent to your cellphone? (Nmiss = 30) | No | 81 (78.6) | 49 (92.5) | 130 (83.3) | 0.03a |

| Yes | 22 (21.4) | 4 (7.5) | 26 (16.7) | ||

| Do you ever use your cellphone to do the following? (yes/no) | |||||

| Send or receive email, text, or instant message (Nmiss = 39) | No | 28 (29.5) | 37 (71.2) | 65 (44.2) | <0.0001a |

| Yes | 67 (70.5) | 15 (28.8) | 82 (55.8) | ||

| Access the internet (Nmiss = 40) | No | 42 (44.2) | 41 (80.4) | 83 (56.8) | <0.0001a |

| Yes | 53 (55.8) | 10 (19.6) | 63 (43.2) | ||

| Download applications (Nmiss = 41) | No | 50 (53.8) | 43 (82.7) | 93 (64.1) | 0.0005a |

| Yes | 43 (46.2) | 9 (17.3) | 52 (35.9) | ||

| Look for information about glaucoma or glaucoma treatment (Nmiss = 41) | No | 79 (84.9) | 52 (100.0) | 131 (90.3) | 0.003b |

| Yes | 14 (15.1) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (9.7) | ||

(≥70).

N (Column %).

Chi-square test.

Fisher exact test.

Discussion

In this study among 164 glaucoma patients, we found a self-reported nonadherence rate of 26% to ocular hypotensive agents. Those who were older were more likely to be adherent to their medications. There was no relationship between adherence and technology use. Those who were older were less likely to use the internet and a cellphone regularly and were less likely to want to receive information about glaucoma by e-mail, internet, or cellphone. Those who were nonadherent were more likely to have had a negative experience during their last time they searched for information about glaucoma online and were also more likely to feel confused about the information they found.

The medication nonadherence rate of 26% reported by patients in our sample is similar to other studies of self-reported adherence.5,18,19 While this rate may seem low, we know that medication nonadherence is subject to interpretation depending on the method of data collection and definition of adherence. Rates of nonadherence are known to be lower when using self-reporting as the method of data collection in comparison to electronic dosing monitors20 or pharmacy refill data.21 These differences explain the large range 5–80% of nonadherence rates in various populations.22 Younger age has also been shown to be correlated with nonadherence in multiple studies.17,21,23 In fact, younger age was used as a factor in a predictive model for nonadherence developed from the Travatan Dosing Aid study.24

Nonadherent patients were younger and used technology more regularly. In contrast to a study conducted by Friedman et al.,25 in which patients who derived all their glaucoma knowledge from their physicians had lower adherence rates than those who searched for additional knowledge on their own, we found no difference in rates of using the internet to learn about glaucoma between adherent and nonadherent patients. As our questionnaire was administered several years after Friedman's 2008 article,25 our findings may reflect the rapid increase in the number of Americans using the internet, especially among those over the age of 65 years.11 While those with college educations (95%), high earners (97%), and urban or suburban dwellers (85%) are still more likely to be internet users in national studies, the gaps between users and nonusers across sociodemographic categories has significantly narrowed.11 In our population, ∼80% owned a computer as well as a cellphone. This finding echoes a national Pew Research study in which 73% of American adults aged 18 years or older owned a desktop or laptop computer and 92% owned a cellphone.26

There is currently a disconnect between how glaucoma patients would like to use the internet as a resource in their disease self-management and current practices. Though the majority of patients in this study were interested in receiving information about glaucoma via e-mail or the internet only 14% had ever received recommendations regarding Web-based glaucoma resources from their physician. The majority of patients in this sample found the information they found online about glaucoma to be helpful, yet only one-third found resources online that could meet their emotional needs. This issue was more salient for nonadherent patients who were more likely to report feeling confused about online glaucoma information and more likely to have a negative experience searching for glaucoma information online.

Adherence to treatment for chronic disease is associated with one's perception of that disease. Among 117 participants with hypertension, Hsiao et al. found that those who were less adherent were more likely to have a negative perception of hypertension—including anger, fear, anxiety, or depression—than those with better medication adherence.27

Folk wisdom has long taught that positive emotions may improve health—Shakespeare wrote “Frame your mind to mirth and merriment, which bars a thousand harms and lengthens life,” in the Taming of the Shrew in the turn of the 17th century. Recent advances in the science of emotion have demonstrated that people who have a tendency toward positive thinking have a higher likelihood of being able to cope well with adversity.28 Thus, the fact that nonadherent glaucoma patients had a more negative experience learning about glaucoma may contribute to this cycle of negative disease perception. It is possible that their online searches were frustrating, making these patients less inclined to follow the medication recommendations. Alternatively, negative reactions to their disease diagnosis may have colored their experience surfing the net. In either case, providing additional emotional support to patients with poor medication adherence and connecting them to high-quality glaucoma education resources may be critical in helping them better self-manage their chronic disease.

Promising examples of how to provide additional emotional support and disease specific resources comes from diabetes management. In one randomized controlled trial, medical assistants who had basic diabetes knowledge were trained as health coaches. Health coaches are trained to listen, provide emotional support, and help people find their own solutions to their problems. The visits with the health coaches helped double the number of patients who reached their diabetic goals compared to usual care, which included diabetes education classes.29 A similar approach might be used to support glaucoma patients and better link them to online glaucoma education resources.

Patients desire personalized, one-on-one sessions with eye care providers and printed materials and Websites recommended by providers.30–32 As we design more effective technology-based glaucoma education tools, it will be important to consider how patients prefer to receive information. Technology is continuously evolving. Just as the older age group in this study was not as interested in using their cellphones or the internet to access glaucoma education as the younger cohort was, in 20 years, this younger cohort may no longer be comfortable using the latest technologies that are commonplace. This supposition highlights the need for multimodal glaucoma education materials to provide patients with information in ways that best fit their lifestyles, use of technology, and communication preferences.

This study has a number of limitations. Medication adherence was measured by self-report. We know that patients and physicians overestimate adherence to glaucoma medications.18 One study showed that while electronic monitoring demonstrated that 55% of patients were adherent, the adherence rates estimated by the patients and physicians were 95% and 77%, respectively.19 Additionally, our study population was a convenience sample between two specialty glaucoma clinics in Michigan and Maryland, which may not be representative of the general glaucoma population. We did not elicit information regarding race/ethnicity, nor did we perform a chart review to determine glaucoma severity; both of these factors have been associated with medication adherence in other studies.6–8,22,33

The majority of glaucoma patients are interested in learning about glaucoma online, yet few physicians are directing their patients toward high-quality resources. Some patients, especially those who are younger and poorly adherent, are seeking out online glaucoma resources on their own. Many find their searches unhelpful, confusing, or negative. This generation of internet-savvy glaucoma patients is aging at a time of growing emphasis on patient-centered care and projected ophthalmologist workforce shortages,34 making it increasingly important to ensure that they have ancillary materials and support to help them understand their disease and treatment. This is an opportunity for physicians to create appropriate, high quality online glaucoma resources and direct patients toward these resources to support disease self-management. In conjunction with educational resources, we should also create a broader system of supports to help glaucoma patients manage their disease, such as how health coaches are helping patients take control of their diabetes. Innovation is needed to leverage technology to create easy-to-navigate, supportive programs for glaucoma patients, especially those with poor adherence.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Mr. Taylor Blachley for the work on statistical analysis provided for this study. This project was funded by the National Eye Institute (1K23EY025320-01A1) and a Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award (PANC). The sponsor or funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Disclosure Statement

Aerie Pharmaceuticals, consultant and stock options (A.L.R.); Biolight Pharmaceuticals, consultant (A.L.R.), Glaukos, stock options (A.L.R.); Alcon Research Institute, consultant (P.P.L.), Center for Disease Control and Prevention, consultant (P.P.L.), Pfizer, GSK, Merck, Medco Health Solutions, Vital Springs Health Technology stock (P.P.L.). None of the financial disclosures are relevant to this research.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). Prevention of Blindness and Visual Impairment: Causes of blindness and visual impairment 2010. Available at www.who.int/blindness/causes/en (last accessed July1, 2016)

- 2. Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng CY. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2014;121:2081–2090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Garway-Heath DF, Crabb DP, Bunce C, Lascaratos G, Amalfitano F, Anand N, et al. Latanoprost for open-angle glaucoma (UKGTS): A randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:1295–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leske MC, Heijl A, Hussein M, Bengtsson B, Hyman L, Komaroff E, et al. Factors for glaucoma progression and the effect of treatment: The early manifest glaucoma trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121:48–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reardon G, Kotak S, Schwartz GF. Objective assessment of compliance and persistence among patients treated for glaucoma and ocular hypertension: A systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence 2011;5:441–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rossi GC, Pasinetti GM, Scudeller L, Radaelli R, Bianchi PE. Do adherence rates and glaucomatous visual field progression correlate? Eur J Ophthalmol 2011;21:410–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sleath B, Blalock S, Covert D, Stone JL, Skinner AC, Muir K, et al. The relationship between glaucoma medication adherence, eye drop technique, and visual field defect severity. Ophthalmology 2011;118:2398–2402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stewart WC, Chorak RP, Hunt HH, Sethuraman G. Factors associated with visual loss in patients with advanced glaucomatous changes in the optic nerve head. Am J Ophthalmol 1993;116:176–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Eye Institute. U.S. Age-Specific Prevalence Rates for Glaucoma by Age and Race/Ethnicity. 2010. Available at https://nei.nih.gov/eyedata/glaucoma (last accessed July10, 2016)

- 10. Fox S, Duggan M. Health Online 2013. Available at www.pewinternet.org/2013/01/15/health-online-2013 (last accessed July10, 2016)

- 11. Perrin A, Duggan M. Americans Internet Access: Percent of Adults 2000–2015. Available at www.pewinternet.org/2015/06/26/americans-internet-access-2000-2015 (last accessed July10, 2016)

- 12. Boland MV, Chang DS, Frazier T, Plyler R, Jefferys JL, Friedman DS. Automated telecommunication-based reminders and adherence with once-daily glaucoma medication dosing: The automated dosing reminder study. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014;132:845–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saeedi OJ, Luzuriaga C, Ellish N, Robin A. Potential limitations of e-mail and text messaging in improving adherence in glaucoma and ocular hypertension. J Glaucoma 2015;24:e95–e102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zulman DM, Kirch M, Zheng K, An LC. Trust in the internet as a health resource among older adults: Analysis of data from a nationally representative survey. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kreps GL, Neuhauser L. New directions in eHealth communication: Opportunities and challenges. Patient Educ Couns 2010;78:329–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:348–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17. Newman-Casey PA, Robin AL, Blachley T, Farris K, Heisler M, Resnicow K, et al. The most common barriers to glaucoma medication adherence: A cross-sectional survey. Ophthalmology 2015;122:1308–1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kass MA, Meltzer DW, Gordon M, Cooper D, Goldberg J. Compliance with topical pilocarpine treatment. Am J Ophthalmol 1986;101:515–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Okeke CO, Quigley HA, Jampel HD, Ying GS, Plyler RJ, Jiang Y, et al. Adherence with topical glaucoma medication monitored electronically the Travatan Dosing Aid study. Ophthalmology 2009;116:191–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dreer LE, Girkin C, Mansberger SL. Determinants of medication adherence to topical glaucoma therapy. J Glaucoma 2012;21:234–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jones JP, Fong DS, Fang EN, Mesirov CA, Patel V. Characterization of glaucoma medication adherence in Kaiser Permanente Southern California. J Glaucoma 2016;25:22–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Olthoff CM, Schouten JS, van de Borne BW, Webers CA. Noncompliance with ocular hypotensive treatment in patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension an evidence-based review. Ophthalmology 2005;112:953–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cohen Castel O, Keinan-Boker L, Geyer O, Milman U, Karkabi K. Factors associated with adherence to glaucoma pharmacotherapy in the primary care setting. Fam Pract 2014;31:453–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chang DS, Friedman DS, Frazier T, Plyler R, Boland MV. Development and validation of a predictive model for nonadherence with once-daily glaucoma medications. Ophthalmology 2013;120:1396–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Friedman DS, Hahn SR, Gelb L, Tan J, Shah SN, Kim EE, et al. Doctor-patient communication, health-related beliefs, and adherence in glaucoma results from the Glaucoma Adherence and Persistency Study. Ophthalmology 2008;115:1320–1327.e1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anderson M. U.S. Technology Device Ownership: 2015. 2015 Available at www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/29/technology-device-ownership-2015 (last accessed July10, 2016)

- 27. Hsiao CY, Chang C, Chen CD. An investigation on illness perception and adherence among hypertensive patients. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2012;28:442–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL, Barrett LF. Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. J Pers 2004;72:1161–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Willard-Grace R, Chen EH, Hessler D, DeVore D, Prado C, Bodenheimer T, et al. Health coaching by medical assistants to improve control of diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia in low-income patients: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med 2015;13:130–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hoevenaars JG, Schouten JS, van den Borne B, Beckers HJ, Webers CA. Knowledge base and preferred methods of obtaining knowledge of glaucoma patients. Eur J Ophthalmol 2005;15:32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Killeen OJ, MacKenzie C, Heisler M, Resnicow K, Lee PP, Newman-Casey PA. User-centered Design of the eyeGuide: A Tailored Glaucoma Behavior Change Program. J Glaucoma 2016;25:815–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rosdahl JA, Swamy L, Stinnett S, Muir KW. Patient education preferences in ophthalmic care. Patient Prefer Adherence 2014;8:565–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Murakami Y, Lee BW, Duncan M, Kao A, Huang JY, Singh K, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in adherence to glaucoma follow-up visits in a county hospital population. Arch Ophthalmol 2011;129:872–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee PP, Hoskins HD, Jr, Parke DW, 3rd. Access to care: Eye care provider workforce considerations in 2020. Arch Ophthalmol 2007;125:406–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]