Abstract

The caregivers’ perceptions of the patients’ health condition may be biased and induce them to perceive higher needs than patients actually disclose. Our aim was to assess if the level of knowledge and awareness about cancer disease and treatment, and patient participation and assistance differs between caregivers and patients. A descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted across five countries (Italy, United Kingdom, Spain, France and Germany) on a total of 510 participants who directly (patient) or indirectly (caregiver) faced a cancer diagnosis. Investigating this divergence could help to identify possible difficulties in patient–caregiver relationship, eventually improving patient empowerment.

Keywords: health surveys, neoplasm, patient participation, proxy, psycho-oncology

Introduction

In the past decades, empowerment has gained attention in the healthcare literature as an enabler of the transition from a paternalistic to a bio-psychosocial model of care.

Rappaport (1981) defined empowerment as a process aimed at increasing the power of people in their lives, community and groups. Three main aspects of the concept were outlined: it is a social process, it is multidimensional and it is based on a dimension of control, defined as autonomy. The empowerment process promotes and enhances people’s ability to move towards their needs and to recognize and use their resources in problem-solving. Empowered people can reach a high level of autonomy and self-determination, affecting their perceived competence and self-confidence (Rappaport, 1981; Zimmerman, 2000).

The World Health Organization (WHO, 1998) defines empowerment within the healthcare context as ‘a process through which people gain greater control over decisions and actions affecting their health and it should be seen as both an individual and a community process’. Therefore, patient participation and shared-decision making have a key role in this process: if people are informed and engaged in all phases after a cancer diagnosis, they will become more compliant to therapies and have more opportunities to bear the uncertainty (Cutica et al., 2014). In this framework, people are encouraged to take an active role in the care process, to be aware and responsible, to gather relevant information and to adopt a strategy for the management of chronic conditions. This is what it means to become an empowered patient.

Despite decades of study and a stunning amount of empowerment-based interventions described in the literature (Henselmans et al., 2013; Kondylakis et al., 2012, 2013, 2014), a universally accepted definition of the concept has not yet been proposed (Graffigna et al., 2017). Several elements float around this concept, that is, participation, knowledge and awareness, expressing the general aim of the empowering process as giving patients resources to exercise control, manage his or her condition and to make informed decisions over their care process (Cerezo et al., 2016).

Patient empowerment is not to be considered as an individual process, but it also concerns healthcare providers and those who are in the patient’s inner circle. Any relative, partner, friend or neighbour who has a significant personal relationship with, and provides a broad range of assistance for an adult with a chronic or disabling condition can be defined as ‘caregiver’, and often becomes a lifeline during the care process (Glajchen, 2004). Several authors investigated the role of caregivers as a support for the patient as well as the patient–physician relationship (Masterson et al., 2015; Milne et al., 2006; Reinhard et al., 2008).

The caregiver is an active part of the care process and is able to provide a different perspective on the patient’s condition and to support the patient’s participation and self-management. They can observe and evaluate the patient’s condition in different moments and contexts. Moreover, having a different perspective allows caregivers to gather information that patients themselves cannot observe from their subjective point of view (Ahmad et al., 2016).

Dramatic health events (e.g. stroke) and the progression of severe diseases (e.g. an advanced cancer) may impact the patient’s decision-making process, leading close relatives to become surrogate decision-makers of their beloved ones (Bravo et al., 2017). Thus, carers may often become proxy evaluators of patient’s needs and health status. Under different disease conditions (Kozlowski et al., 2015; Moyle et al., 2012; Werntz et al., 2015), quality of life is perceived in a different manner by patients and caregivers: there is high agreement on the global quality of life and physical functioning perception by patients and caregivers, but low agreement for psychosocial aspects related to the patient’s condition. Proxy-related information does not always positively correlate with the patient’s condition, though, and caregivers tend to underestimate patient’s health status (Bravo et al., 2017; Libert et al., 2013). In cancer care, physical and psychological outcomes (e.g. pain, fatigue, depression) show weak to moderate correlations between close relatives and cancer patients (Greig et al., 2005; Poort et al., 2016; Rooney et al., 2013; Tang and McCorkle, 2002).

The attention given in the literature to the caregivers’ perspectives, though, focused on the information relative to patient status or compliance to the treatment. In such a scenario, caregivers may view patients as passive elements and they will focus mainly on information regarding patient health status, in order to provide as much information as possible to the clinician. From this perspective, the clinician could be perceived as the sole decision-making agent, and the patient plays no active decisional role.

Several authors reported that caregivers’ perception of the patient condition may be biased and, in some cases, induce them to perceive higher needs than what patients actually disclose (Hsu et al., 2017; Libert et al., 2013). Consequently, this misperception can lead to a big difference in the level of the patient’s empowerment perceived by the caregiver. Investigating this divergence could help recognize possible difficulties in patient–caregiver relationship and communication. This concern prompted us to seek out works that address the issue of active patient participation, and how patient empowerment is perceived by the caregiver. A comprehensive literature search was designed and conducted by an experienced medical librarian with input from the study investigators. The bibliographic databases Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed, ProQuest Psychology, CINAHL and Scopus were searched. Various combinations of database-specific controlled vocabulary (subject headings) were used, supplemented by keywords, title and abstract terms for the concepts and synonyms relating to patient participation, patient empowerment, caregivers and perception. Papers that looked potentially relevant were examined, as were their bibliographies. Cited articles were also sought via Web of Science. Unfortunately, the literature searches conducted across these databases did not yield any results regarding patient participation and patient empowerment from a caregiver’s perspective.

Therefore, we decided to survey a sample of people who have, or had, the experience of dealing with cancer personally or having someone close to them suffering from this condition.

To this purpose, an exploratory tool was included inside a socio-demographic survey, administered across five European countries. The exploratory tool, specifically developed for the First International Forum on Cancer Patient Empowerment (Milan, Italy, 2017), included six items investigating the desired level of participation and support of the patient in the healthcare pathway, the desired level of access to information included in the patient health records and the perceived level of awareness of the patient on the therapeutic process.

Our objective is to assess if the perception of patients’ knowledge and awareness of the therapeutic process is different between caregivers and patients and if these two groups share the same beliefs about patient participation and involvement. More specifically, we would like to investigate if the caregiver’s perception on what patients should do or receive is coherent with the effective patient’s perspective on the following areas: Access to clinical information, Information availability, Need for information, Patient awareness, Participation in the care process, Support.

Materials and methods

Subjects

According to the First International Forum on Cancer Patient Empowerment, a descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted across five different countries (Italy, United Kingdom, Spain, France and Germany) and followed the inclusion criteria: (1) people with cancer diagnosis, (2) caregivers of patients with a cancer diagnosis and (3) aged 45 years and older. People who were not caregivers or have not faced a cancer diagnosis were excluded.

Participants were divided into two groups according to the response to the item: ‘Have you ever dealt with cancer during your life?’. Possible answers were: (1) I’d rather not say, (2) No, (3) I have met people who had cancer, (4) Yes, I have been involved in the care of someone close to me and (5) Yes, I have experienced it personally. Participants who selected the first three answers were not considered in the study research, ones who selected the fourth were included in the ‘Caregiver’ group, while those who chose the last answer were included in the ‘Patient’ group.

After demographic characteristics, there was a question asking if they had ever dealt with cancer either directly (as patients) or indirectly (caregiver).

Participants were asked to provide information about socio-demographic characteristics, including age, gender, level of education, civil status, place of birth and residence.

Questionnaire

Specific questions investigating knowledge and awareness about cancer disease and treatments, patient participation in the therapeutic process and assistance received by the healthcare system were included in an online survey developed for the First International Forum on Cancer Patient Empowerment (Milan, Italy, 2017). A total of six items evaluated what patients and caregivers would want to receive or received from the healthcare providers during their therapeutic process, using a 4-point Likert-type scale.

The items were as follows:

How important is it for the patient to access his or her medical records, in order to have full control of the disease? (Access to clinical information)

How difficult do you think it is to receive all information associated with the disease from the health facility? (Information availability)

How much information do you think is left unanswered by the healthcare facility? (Need for information)

In your experience, how important is it that the patient be made aware of the care process? (Patient awareness)

How important is it for the patient to be personally involved in the choice of treatment, if other treatments are available? (Participation in the care process)

Do you think it is important for the patient not to face cancer alone? (Support)

Statistical analysis

Data were evaluated using non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney U-test), and statistical significance was determined by p < 0.05. Patients’ and caregivers’ answers to the six items investigating perceived awareness and desired information access in the medical decision-making process were considered.

Results

Participants

From an initial sample of 1781 participants, only 510 satisfied the inclusion criteria (age and type of involvement in the cancer diagnosis) and completed the questionnaire.

A total of 247 participants (female = 57%), with an average age of 63.83 (SD = 9.278) were included in the Patient Group, while 263 participants (female = 54.4%) with an average age of 57.82 (SD = 8.901) were included in the Caregiver Group.

Socio-demographic characteristics are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Patient’s characteristics.

| Patients | N (%) |

|---|---|

| All | 247 |

| Age – mean (SD) | 63.83 (9.278) |

| 45–54 years | 48 (19.4) |

| 55–64 years | 75 (30.4) |

| 65–74 years | 91 (36.8) |

| 75+ | 33 (13.4) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 141 (57.1) |

| Male | 106 (42.9) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 80 (32.4) |

| High school and above | 67 (67.6) |

| Country | |

| France | 49 (19.8) |

| Germany | 61 (24.7) |

| UK | 57 (23.1) |

| Italy | 49 (19.8) |

| Spain | 31 (12.6) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Breast cancer | 96 (38.9) |

| Osteosarcoma | 1 (0.4) |

| Prostate cancer | 37 (15.0) |

| Lung cancer | 11 (4.5) |

| Leukaemia | 9 (3.6) |

| Pancreas cancer | 2 (0.8) |

| Another cancer | 69 (27.9) |

| Missing | 22 (8.9) |

| Civil Status | |

| Single | 28 (11.3) |

| Civil partner | 8 (3.2) |

| Married | 164 (66.4) |

| Separated | 4 (1.6) |

| Divorced | 22 (8.9) |

| Widow/widower | 21 (8.5) |

Table 2.

Caregiver’s characteristics.

| Caregivers | N (%) |

|---|---|

| All | 263 |

| Age – mean (SD) | 57.82 (8.901) |

| 45–54 years | 107 (40.7) |

| 55–64 years | 98 (37.3) |

| 65–74 years | 45 (17.1) |

| 75+ | 13 (4.9) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 143 (54.4) |

| Male | 120 (45.6) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 107 (40.7) |

| High school and above | 156 (59.3) |

| Country | |

| France | 53 (20.2) |

| Germany | 40 (15.2) |

| UK | 45 (17.1) |

| Italy | 54 (20.5) |

| Spain | 71 (27.0) |

| Caregiver self-reported patient diagnosis | |

| Breast cancer | 62 (23.6) |

| Osteosarcoma | 3 (1.1) |

| Prostate cancer | 31 (11.8) |

| Lung cancer | 50 (19.0) |

| Leukaemia | 21 (8.0) |

| Pancreas cancer | 19 (7.2) |

| Another cancer | 63 (24.0) |

| Missing | 14 (5.3) |

| Civil Status | |

| Single | 37 (14.1) |

| Civil partner | 31 (11.8) |

| Married | 133 (50.6) |

| Separated | 5 (1.9) |

| Divorced | 48 (18.3) |

| Widow/widower | 9 (3.4) |

Awareness, participation, information and support

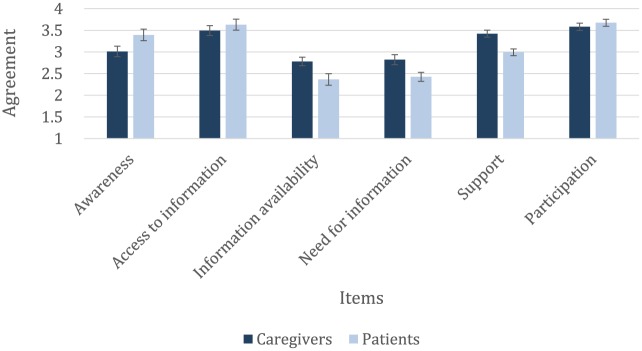

The results showed a significant difference between patients and caregivers in the level of perceived patient’s awareness (U = 23009.000; Z = −4.826; p < 0.001), in the access to clinical information (U = 26475.000; Z = −2.737; p < 0.05), in the availability of information (U = 22401.000; Z = −4.436; p < 0.001), on the need for information (U = 21363.500; Z = −4.416; p < 0.001) and for support (U = 23363.500; Z = −4,735; p < 0.001). No difference was found in the item related to the desire to actively participate to care process (U = 28035.500; Z = −1.817; p > 0.05), see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Average outcomes; blue columns represent the average score for caregivers while the light blue columns refer to the average score of patients.

The rating scale was from 1 (not important at all) to 4 (very important) for all questions.

More specifically, relative to the item investigating the importance for the patient to manage information in their care pathway, caregivers reported a lower patient interest in having access to personal clinical information (M = 3.49) compared with what the patients reported (M = 3.63). The item on information availability, the caregivers reported that patients had more difficulty in obtaining information on the disease from the healthcare system compared with what patients actually expressed themselves (respectively, M = 2.78; M = 2.37). Furthermore, caregivers more than patients indicated that, despite the need for information, many questions remain unsolved (respectively, M = 2.82; M = 2.43).

Referring to the question on awareness, coherently with the aforementioned results, caregivers reported a lower patient awareness of the care process (M = 3.01) compared with what patients actually reported (M = 3.39).

Finally, caregivers (M = 3.42) are more convinced than patients (M = 2.99) that cancer is not a disease that can be coped with alone (support item).

Discussion

The main interest of this exploratory research was to observe the relationship between patients’ self-perception and how they are perceived by caregivers. Self and proxy health information has been studied in the care process of several chronic diseases, including dementia, stroke and cancer (Kozlowski et al., 2015; McMahan et al., 2013; Moyle et al., 2012). These research studies focused on the dyad’s different perception of patient’s health status, symptoms and needs, but, as far as we know, the existing studies did not investigate the different perception on patient participation, knowledge and awareness on the care pathway.

This study proposes an important contribution to the understanding of the cognitive map of patients and caregivers and provides a new perspective for a further investigation of the role of patient perception. The perceived ability of the patient to manage his or her condition may be a crucial element that might affect patients, both individually and within the relationship with informal caregivers and clinicians.

In particular, the results show that even though all participants, regardless of their role, highly value access to information, presence of relational support, awareness and participation to the care process, there are several differences that may highlight a different perception of the patient’s condition.

Patients tend to perceive themselves as more aware of what is happening in the treatment process than the person who supports and facilitates him or her in communication, choices and actions. This finding is consistent with another study in which lung cancer patients evaluated their physical functioning and symptoms, respectively, higher and lower than their relatives (Wennman-Larsen et al., 2007).

The difference in the level of awareness between caregivers and patients is coherent with differences in the perception of information availability and the access to clinical records. Caregivers declare higher difficulty than patients both in obtaining information and answers from clinicians and directly accessing to clinical information. These results could indicate that caregivers tend to perceive the information gathering harder than the patients actually experience and, thus, overestimate the effort necessary for patients to retrieve information. Carers with a poorer relationship functioning may become overprotective, share less information with their beloved ones and stop talking about emotions. This coping style may affect patients’ psychosocial condition, enhance patient’s level of distress and decrease self-efficacy (Regan et al., 2015). Moreover, caregivers are also more convinced than patients that cancer has to be faced together: some studies showed that all family members would like to cooperate in dealing with disease and its related symptoms, even if it may increase emotional burden and distress, impact the caregiver’s perception of his role and increase the occurrence of psychological problems (Deshields et al., 2012; Northouse et al., 2010; Schumacher et al., 2008; Spillers et al., 2008). They seek to cope with the disease as a couple, both sharing emotions and giving support and collaborating with the partner to overcome cancer-related problems (Regan et al., 2015).

Our study not only confirms this finding but also suggests that the aforementioned family need is not completely in line with patients’ perspective and needs. The results seem to suggest that patients can or want to manage their journey alone much more than what caregivers think. On the other hand, the need to be responsible for their own health may be wrongly perceived by caregivers as a lack of patient awareness of the care pathway and an overestimation of patient’s need of support. Patients may even underestimate their need of support in order to preserve their perception of independence (Nijboer et al., 1999; Sharpe et al., 2005).

The aforementioned differences, however, do not reflect a gap in desired involvement between patients and caregivers: both, in fact, equally believe that patient’s participation to the care pathway is important. Therefore, differences emerged in previous answers should not be due to different ideas or values of patient’s participation in the care process. Consistently with the literature, participants expressed a great interest in receiving high-quality information, which is a key factor to empower the patient, improve health literacy and improve awareness on their condition in order to make informed decisions (Cerezo et al., 2016; Davis et al., 2002; Oldach and Katz, 2014).

Several limitations have to be accounted for when considering these results. Although we received information from a large sample, the aggregation of our items to a survey collected via a CAWI methodology largely affected the amount of information we could collect.

Moreover, the data collection from individuals did not allow us to collect paired information from dyads, hence it does not allow us to make assumptions about specific dyads but only average results by patients and caregivers taken individually. For this reason, the extent of our implications on the relationship between patients and caregivers should be considered as a general indication of caregivers’ and patients’ opinions.

Due to the exploratory nature of this study, these preliminary results should not be considered informative in a direct clinical perspective, but more as an indicator of a phenomenon that should be more thoroughly investigated.

Future studies should further investigate the caregivers’ group characteristics by differentiating across variables such as relationship type (e.g. couple, parent–child, survivor–professional caregiver), length of caregiving and country. Primary caregivers often provide 24/7 care and take over activities of daily living for the patient, even if they are not always clinically and psychologically trained to carry out the caregiving role (Northouse et al., 2010).

Conclusion

The opportunity to observe the patient’s condition from two different perspectives may help to better understand it from a relational perspective. In a crisis situation, such as a cancer diagnosis, it is important having someone able to comprehend all the information regarding treatment options and prognosis and also to help the patient in day-to-day life (Ahmad et al., 2016). On the other hand, informal caregivers, trying to do the best to help their beloved ones, look at the same situation from a different perspective: their psychological burden and unmet needs may have an influence over the perception of patient’s status, ability to cope with his situation and, possibly, inducing a biased view of their condition.

We believe that this preliminary overview of caregivers’ perception of patients could highlight a possible critical point that may lead to miscommunications and misperceptions between patients and people that are close to them during the care process.

In fact, other people’s views often affect our self-perception and behaviour. The self-efficacy model – that states that the self-evaluation of skills stems from both personal, successful experiences and other people’s feedback (Bandura, 1997) – may be applied here. In this specific context, it implies that caregiver’s perception may have a detrimental influence on the patient’s perception of his or her ability to manage and deal with the treatment process. In other words, relatives’ perception of patient’s abilities to cope with cancer may affect the patient’s self-confidence and awareness about their therapeutic plan, decreasing the level of patient empowerment.

Nevertheless, it is important to stress that the perceived level of patients’ awareness does not necessarily reflect the actual degree of knowledge or consciousness of the therapeutic process, but it merely depicts the patient’s, or caregiver’s, point of view.

Despite the several limitations of the study due to its exploratory nature, we believe that its contribution may lead to further research on the relational implications of the caregiver’s perspective. With this aim the effect of caregiver’s perception on the patient’s self-efficacy and empowerment may be investigated in more detail in order to understand possible consequences on the patient’s condition.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ahmad FS, Barg FK, Bowles KH, et al. (2016) Comparing perspectives of patients, caregivers, and clinicians on heart failure management. Journal of Cardiac Failure 22(3): 210–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1997) Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo G, Sene M, Arcand M. (2017) Reliability of health-related quality-of-life assessments made by older adults and significant others for health states of increasing cognitive impairment. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 15(1): 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerezo PG, Juvé-Udina M-E, Delgado-Hito P. (2016) Concepts and measures of patient empowerment: A comprehensive review. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP 50(4): 667–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutica I, Vie GM, Pravettoni G. (2014) Personalised medicine: The cognitive side of patients. European Journal of Internal Medicine 25(8): 685–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TC, Williams MV, Marin E, et al. (2002) Health literacy and cancer communication. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 52(3): 134–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshields TL, Rihanek A, Potter P, et al. (2012) Psychosocial aspects of caregiving: Perceptions of cancer patients and family caregivers. Supportive Care in Cancer 20(2): 349–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glajchen M. (2004) The emerging role and needs of family caregivers in cancer care. The Journal of Supportive Oncology 2(2): 145–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graffigna G, Barello S, Riva G, et al. (2017) Fertilizing a patient engagement ecosystem to innovate healthcare: Toward the first Italian consensus conference on patient engagement. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greig ML, Chow E, Bovett G, et al. (2005) Level of concordance between proxy and cancer patient ratings in brief paininventory. Supportive Cancer Therapy 3(1): 54–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henselmans I, de Haes HC, Smets EM. (2013) Enhancing patient participation in oncology consultations: A best evidence synthesis of patient-targeted interventions. Psycho-Oncology 22(5): 961–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu T, Loscalzo M, Ramani R, et al. (2017) Are disagreements in caregiver and patient assessment of patient health associated with increased caregiver burden in caregivers of older adults with cancer? The Oncologist 22(11): 1383–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondylakis H, Kazantzaki E, Koumakis L, et al. (2014) Development of interactive empowerment services in support of personalised medicine. Ecancermedicalscience 8: 400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondylakis H, Koumakis L, Genitsaridi E, et al. (2012) IEmS: A collaborative environment for patient empowerment. In: 2012 IEEE 12th international conference on Bioinformatics & Bioengineering (BIBE), November 2012, pp. 535–540. IEEE; Available at: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6399770 [Google Scholar]

- Kondylakis H, Koumakis L, Tsiknakis M, et al. (2013) Smart recommendation services in support of patient empowerment and personalized medicine. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies 25: 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski AJ, Singh R, Victorson D, et al. (2015) Agreement between responses from community-dwelling persons with stroke and their proxies on the NIH Neurological Quality of Life (Neuro-QoL) short forms. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 96(11): 1986–92e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libert Y, Merckaert I, Slachmuylder J-L, et al. (2013) The ability of informal primary caregivers to accurately report cancer patients’ difficulties. Psycho-Oncology 22(12): 2840–2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahan RD, Knight SJ, Fried TR, et al. (2013) Advance care planning beyond advance directives: Perspectives from patients and surrogates. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 46(3): 355–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masterson MP, Hurley KE, Zaider T, et al. (2015) Toward a model of continuous care: A necessity for caregiving partners. Palliative & Supportive Care 13(5): 1459–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne DJ, Mulder LL, Beelen HCM, et al. (2006) Patients’ self-report and family caregivers’ perception of quality of life in patients with advanced cancer: How do they compare? European Journal of Cancer Care 15(2): 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyle W, Gracia N, Murfield JE, et al. (2012) Assessing quality of life of older people with dementia in long-term care: A comparison of two self-report measures. Journal of Clinical Nursing 21(11–12): 1632–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijboer C, Triemstra M, Tempelaar R, et al. (1999) Determinants of caregiving experiences and mental health of partners of cancer patients. Cancer 86(4): 577–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, et al. (2010) Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 60(5), 317–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldach BR, Katz ML. (2014) Health literacy and cancer screening: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling 94(2): 149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poort H, Peters ME, Gielissen MF, et al. (2016) Fatigue in advanced cancer patients: Congruence between patients and their informal caregivers about patients’ fatigue severity during cancer treatment with palliative intent and predictors of agreement. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 52(3): 336–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport J. (1981) In praise of paradox: A social policy of empowerment over prevention. American Journal of Community Psychology 9(1): 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan TW, Lambert SD, Kelly B, et al. (2015) Couples coping with cancer: Exploration of theoretical frameworks from dyadic studies. Psycho-Oncology 24(12): 1605–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard SC, Given B, Petlick NH, et al. (2008) Supporting Family Caregivers in Providing Care. In: Hughes RG. (ed.) Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney AG, McNamara S, Mackinnon M, et al. (2013) Screening for major depressive disorder in adults with glioma using the PHQ-9: A comparison of patient versus proxy reports. Journal of Neuro-Oncology 113(1): 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher KL, Stewart BJ, Archbold PG, et al. (2008) Effects of caregiving demand, mutuality, and preparedness on family caregiver outcomes during cancer treatment. Oncology Nursing Forum 35(1): 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe L, Butow P, Smith C, et al. (2005) The relationship between available support, unmet needs and caregiver burden in patients with advanced cancer and their carers. Psycho-Oncology 14(2): 102–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillers RL, Wellisch DK, Kim Y, et al. (2008) Family caregivers and guilt in the context of cancer care. Psychosomatics 49(6): 511–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang ST, McCorkle R. (2002) Use of family proxies in quality of life research for cancer patients at the end of life: A literature review. Cancer Investigation 20(7–8): 1086–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennman-Larsen A, Tishelman C, Wengström Y, et al. (2007) Factors influencing agreement in symptom ratings by lung cancer patients and their significant others. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 33(2): 146–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werntz AJ, Dodson CS, Schiller AJ, et al. (2015) Mental health in rural caregivers of persons with dementia. SAGE Open 5(4): 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (1998) Health Promotion Glossary. Geneva: WHO; Available at: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/about/HPRGlossary1998.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA. (2000) Empowerment theory. In: Rappaport J, Seidman E. (eds) Handbook of Community Psychology. Boston, MA: Springer, pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]