Abstract

We conducted in-depth interviews guided by the Andersen–Newman Health Service Utilization Framework to understand perceptions of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with 25 young, black men who have sex with men (YBMSM) in the Southern United States. The mean age of participants was 24 years; 21 were insured; and 18 had a regular source of care. Five major themes emerged: (i) stigma related to being black, gay and living in the South; (ii) lack of discussion in the black community about HIV prevention and sexual health; (iii) stigma related to PrEP; (iv) medical mistrust; and (v) low perceived need to be on PrEP. This study presents formative qualitative work that underscores the need for behavioral interventions to address intersectional stigma and perceptions of risk among YBMSM in the South, so that PrEP is no longer viewed as a drastic step but rather as a routine HIV prevention strategy.

Keywords: young, black men who have sex with men, PrEP, sexual silence

Introduction

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention has consistently reported that in the United States the majority of new cases of HIV are among men who have sex with men (MSM).1 While MSM account for only 2–3% of the US population, in 2015 they represented 63% of incident HIV infections.2–5 In particular, young, black MSM (YBMSM) account for the majority of all new HIV infections in the United States.6 Further, 60% of all black MSM diagnosed with HIV live in the South.7 Sobering analyses suggest that if current HIV infection rates persist, one in two black MSM will become infected with HIV in their lifetime.8

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of daily oral Truvada® for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in 2012 added an important biomedical HIV prevention strategy to the HIV prevention tool kit.9–15 While uptake of PrEP was initially slow among MSM, rates of PrEP prescriptions have been on the rise for white MSM. However, at the 2018 Conference for Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported that while two-thirds of the population who have indications for PrEP are African American, they account for the smallest percentage of prescriptions.16,17 Unfortunately, these findings were not unexpected based on reports of differential uptake of PrEP among white MSM when compared with black populations who are currently disproportionately infected in the domestic epidemic.18 More so, prescriptions of PrEP are written the least in the Southern United States where uptake of highly effective HIV prevention strategies is needed most.19

To better understand individual, interpersonal, and contextual factors influencing uptake of PrEP among YBMSM in the South, we conducted in-depth interviews with 25 YBMSM in a southern, urban US setting. Constructs from the Andersen–Newman Health Service Utilization Framework were used to guide the study and aid in interpretation of factors influencing perceptions of PrEP in this highly vulnerable population.

Methods

Design

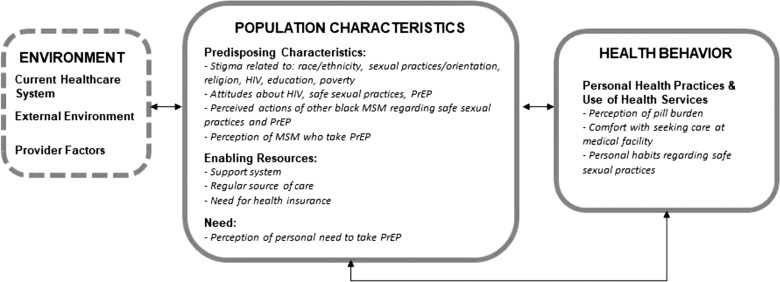

We conducted a phenomenological qualitative study framed within the Andersen and Newman (ANM) Framework of Health Services Utilization20 (Fig. 1). By conducting a phenomenological study grounded in the ANM framework, we were able to explore lived experiences and the individual, interpersonal, and contextual factors that influence perceptions of PrEP among YBMSM. We explored specifically two constructs within this model: population characteristics and health behaviors. Population characteristics in the ANM are considered to be a function of three factors: predisposing, enabling, and need.20–22 (i) Predisposing factors are characteristics that occur independent of the health behavior. (ii) Enabling factors influence a health behavior either positively or negatively, and include individual, interpersonal, and community relationships. (iii) Finally, need factors immediately influence a health behavior through perceived and evaluated needs for medical care. Health behavior is determined by evaluating personal health practices and health service utilization independent of the health behavior being evaluated.

FIG. 1.

Andersen and Newman Health Services Utilization Framework. Conceptual model adapted from Andersen's Behavioral Model (ABM). Items in boxes are constructs of ABM.

A qualitative in-depth interview guide grounded in the ANM was developed and revised based on feedback from key stakeholders in the community, including PrEP providers, YBMSM, community-based organization (CBO) employees, and researchers with field expertise. Twenty-five in-depth interviews were conducted. The transcripts of these interviews were reviewed for content in several iterations by a multi-disciplinary panel with expertise in HIV, qualitative methods, infectious disease, social work, and health behavior. The University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board approved study procedures. Written informed consent was obtained from participants before each interview.

Participants

We used a convenience sample of self-reported HIV-negative, cisgender men who reported having had sex with men, black race, and were between the ages of 16 and 29 years who live in the greater Birmingham–Hoover metropolitan area. Participants were recruited using study fliers posted in two local community-based organizations who specialize in providing care to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community in Birmingham. Exclusion criteria included being HIV positive, not black race, younger than 16 or older than 29 years of age, non-English speaking, reporting female gender, or having psychiatric illness, making it impossible to conduct the in-depth interviews.

Procedure

The experienced qualitative interviewers identified as black, and included two cisgender females and one cisgender MSM. These research staff were trained on the current domestic HIV epidemic, HIV prevention tools, including PrEP, and practiced conducting mock interviews before conducting interviews with participants. Interviews were conducted in a private meeting space, and all interviews were audio recorded (Table 1). Before each interview, participants were asked to complete a brief demographic survey. Each participant received US$30 remuneration upon completion of the interview.

Table 1.

Interview Topics and Questions

| Interview topic | Questions |

|---|---|

| Sexual identity Stigma related to sexual orientation |

|

| HIV knowledge, attitudes, and stigma |

|

| Safe sex practices |

|

| PrEP knowledge, attitudes, and stigma PrEP |

|

| Perception of need to take PrEP |

|

| Perception of pill burden |

|

| Knowledge of where and how to access PrEP |

|

| Willingness to take PrEP |

|

PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STIs, sexually transmitted infections.

Data management and analysis

Digital audio recordings from each session were securely uploaded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service. Audio recordings and transcripts were stored in encrypted drives. NVivo software version 11 (QSR International) was used to aid in coding. To develop an initial codebook, the first four transcripts were independently coded by two qualitative researchers (C.M. and S.S.) using a combination of thematic coding and a priori coding based upon ANM.23 Thematic coding allowed for a flexible and open way to condense data into meaningful groups, while a priori coding allowed for the streamlining of codes based on constructs from ANM.

After the first four transcripts were independently coded, the coders (C.M. and S.S.) met to compare notes, reconcile and clarify the codebook. Through an iterative process involving a series of meetings with the research team (C.M., S.S., L.E., and J.M.T.) and a subsequent round of coding, fine codes were allowed to emerge inductively from the data and subthemes identified. A final round of coding was conducted by one researcher (C.M.) to ensure that all data from identified subthemes were sufficiently represented and any contradictions in the data were explored. The final coding was discussed and approved by the whole research team. Upon completion of coding, the research team used both inductive and deductive reasoning to establish prominent themes.

Results

All 25 participants were black cisgender men who reported having had sex with other men. Participant ages ranged from 18 to 29 years with the majority (64%) of participants between 18 and 24 years, and a median age of 24 years. Self-descriptions of sexual identity varied, with the majority of participants (64%) reporting being gay. Eighty-four percent of our participants had health insurance, and 72% reported having regular healthcare. Only four of the participants reported currently using PrEP, but 84% said that they would be willing to use PrEP in the future (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Study Population

| Characteristics | Total = 25, N (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age | 24 |

| Has health insurance | |

| Yes | 21 (84) |

| No | 4 (16) |

| Regular source of healthcare | |

| Yes | 18 (72) |

| No | 7 (28) |

| Self-described sexual identity | |

| Gay/MSM/same gender loving | 16 (64) |

| Bisexual or queer | 6 (24) |

| Gender nonconforming | 2 (8) |

| Heterosexual | 1 (4) |

| Aware of PrEP | |

| Yes | 25 |

| No | 0 |

| Willing to take PrEP | |

| Yes | 21 (84) |

| No | 4 (16) |

| On PrEP | |

| Yes | 4 (16) |

| No | 21 (84) |

MSM, men who have sex with men; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Common emerging themes

We identified five overarching themes grounded in the ANM conceptual framework from analysis of the interviews conducted with YBMSM in relation to accessing PrEP. These themes existed across constructs within our framework and, therefore, are not presented solely within the context of each individual construct. (i) Many participants expressed intersectional stigma related to race and sexual orientation, that is, related to being a black man who had sex with other men living in the South. (ii) This was felt to be a consequence of a lack of discussion in the black community related to sexual health and HIV prevention. (iii) Many participants perceived a high level of stigma in the black community related to PrEP. (iv) Many participants also felt that there was lack of information and clarity related to PrEP side effects, and that medical distrust may lead to decreased uptake of PrEP. (v) Finally, many participants reported a low perceived personal risk of contracting HIV and, therefore, a low need to take PrEP. Taken together, while most participants stated that they would be willing to take PrEP at the end of the interviews, most expressed several concerns and, in many instances, made statements that indicated their lack of willingness to use PrEP. Below, we explore each of these themes and present subthemes with related sample participant quotes.

Stigma related to being black, gay, and living in the South

Of the 25 men interviewed, most discussed the difficulties they experienced because of their multiple identities within their black community. They felt that the stigmas they reported, both internalized and perceived/experienced, were compounded by growing up in the Southern United States. Many also reported stigma related to organized religion, but none specifically discussed spirituality and its influence (contextually) on their ability to feel comfortable accessing HIV prevention services such as PrEP:

“I mean in the South, it's definitely I would say more difficult than anywhere in the LGBTQ community…Like being in the South, because I was raised in a real Christian environment, kind of overly religious when I think about it, but I just heard bisexuality is a cover up.”—CP121, 19 years old, Bisexual

“Even in church, that is what we would hear all the time. HIV is God's punishment for gay people, stuff like that.”—CP112, 21 years old, Gay

One participant expressed that his profound feeling of personal shame in being gay prevented him from being able to feel comfortable engaging in any sex act with another man:

“I don't feel like I've ever had true peace of mind in a sexual encounter in my life, which is kind of sad. Because when you talk to straight people about that, it's like a disconnect. They have no idea what that is because there's no shame associated with their sex. So much shame associated with gay people, gay sex and all that stuff…”—CP120, 29 years old, Gay

A subtheme emerged from many participants who expressed their feeling that being gay was the antithesis of perceived masculinity in the black community, which also affected their perception of their own masculinity:

“…you also have to have the conversation about homosexuality and competency around that, which kind of contradicts the super-masculinity of the African American community. You know, you have to be a man's man in the black community.”—CP116, 22 years old, Homosexual

“So, like, the black community foundationally, I think has an idea of a conceptualized masculinity that homosexuality naturally seems to kind of not claim, or most people that you can't—I think a lot of it becomes a fear that you can't be a man, or something if you're gay for a lot of people.”—CP100, 20 years old, Gay

This decreased perception of masculinity was also related to the struggle most participants felt with either intentional or unintentional disclosure of their sexuality to other male family members. The stories varied in intensity from some participants reporting their perception of their father's disappointment in them to others losing complete contact with their loved ones:

“After he found out, I could hear him…It is like night when I cut my TV off. I could just hear him crying. It was just like I felt like I had disappointed him.”—CP106, 19 years old, Nonconforming

“Yeah it was…it was awful…The last thing he said to me was, ‘If this is the kind of shit you want to do, then you can just never talk to me again’.”—CP118, 19 years old, Queer

Silence in the black community about HIV prevention and sexual health

Scattered throughout most of the interviews was one underlying theme that was likely a consequence of many of the other inter-related stigmas regarding race, sexual identity, and geographical location described above. Multiple participants described a silence in the black community regarding sexual health and HIV prevention. This theme was exemplified in the multiple stories of participants having family members who were either infected or had died from HIV, in the context of a lack of understanding or discussion in their family about HIV or sexual health:

“I did not know much about it. It was not something that was really talked about especially in my hometown where I grew up. As a matter of fact, I actually grew up. It was not until the age of, I think 17 when I actually had the opportunity to ask the question of a doctor.”—CP108, 29 years old, Gay

“You know, white gay men are still white men. So they still, from their beginnings, are higher statistically like to be exposed to proper safe sex talks, safe sex training, proper healthcare talks, proper health insurance from their families, versus in the African American community you already have a disparity as far as healthcare and sex talk goes in general.”—CP116, 22 years old, Homosexual

“I feel like a lot of us hide what it is that we're going through, or who we actually are, just because we can't be open about it. And that kind of hurts us even more because we don't go to the health departments and, I guess, get tested because we're afraid. And if we have it, who do we tell? Where do we find, I guess, that community?”—CP117, 22 years old, Bisexual

Stigma related to PrEP

Most participants were aware of PrEP, but felt that there was a lot of stigma surrounding it that translated to lack of uptake in the black community among YBMSM. They reported concerns about being perceived as a PrEP or Truvada “whore” if their peers or potential partners knew that they were taking PrEP:

“I've heard the term Truvada whore. Like shaming people who take it. It's like in the gay community, it's like gay shaming. People think that guys who are on PrEP are overly promiscuous and all they want to do is have all this unprotected sex, these orgies and all this stuff.”—CP120, 29 years old, Gay

“Okay… this is what it is. Other people are like, ‘Okay, well, if you're doing PrEP, then what else are you doing? Are you just out here spreading it low, spreading it wide?”—CP101, 25 years old, Gay

A few participants also expressed their concerns about PrEP use directly leading to increased promiscuity among users as a major barrier for their own use of PrEP. This led some to be concerned about initiating PrEP themselves, because they were concerned about not only stigma related to PrEP but also actual increase in promiscuity as a result of its use:

“So it's like, okay, well, as long as you ain't giving me HIV, let's sleep naked—I mean, let's have unprotected sex. And to me that's just—I don't know, it's just not right. It's not right at all. And that's my only problem with PrEP. It's like a lot of people that on PrEP now, it's like oh, we don't need a rubber now.”—CP124, 29 years old, Gay

“But at the same time, I think it'd cause more sexual activity. Because some people would feel like they're just too safe.”—CP112, 25 years old, MSM

A subtheme also emerged of a few participants feeling a lot of the stigma surrounding PrEP was due to its association with HIV. There was a concern that by being on PrEP, peers in their community would assume that they were already infected:

“Not really. I feel like that, with PrEP and stuff, people are so scared of what people is going to think about them taking PrEP, if they see their PrEP bottle, the pill bottle, the feel like people just going to think that it's something else…”—CP107, 21 years old, MSM, PrEP User

Medical distrust

Medical distrust was expressed by many participants. Some also expressed concerns among peers about PrEP causing people to be at increased risk of getting HIV. The few participants who were on PrEP expressed that a lot of their friends and family were very concerned about them taking the biomedical prevention tool. Most expressed fear and medical distrust as the main reasons for concerns:

“The older generation, the ones stuck in their ways, the ones who think, oh, the government is just trying to get us. And I done heard so much stuff. Why you putting that stuff? That stuff going to kill you faster than HIV…”—CP107, 21 years old, MSM, PrEP user

“Every single person I've told has asked me that flat out. ‘This isn't going to make you get it, is it?’ No, that's the opposite of it.”—CP120, 29 years old, Gay, PrEP user

“A lot of friends have…asked me does the medication actually work? And then the second thing that they're most concerned about is are they being used for experimental guinea pigs for the medication…Will I develop HIV or will I be more at risk for contracting HIV?”—CP122, 24 years old, Gay, PrEP user

One participant reported such intense medical distrust that he expressed more concern with having PrEP delivered as a long-acting intramuscular injection, due to fear that this would more likely indicate the medical community trying to infect him with HIV:

“I'm so paranoid so this is to state the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment and I always, in back of my mind, because of the history is healthy skepticism, that the shot may be to inject HIV into people and try to see what it does or it's not really to protect against HIV, maybe it's something else.”—CP109, 25 years old, Queer

Low perceived need to be on PrEP

Although the majority of participants stated their overall willingness to take PrEP, they also expressed low perceived need to be on PrEP due to low risk. Interestingly, upon evaluation of full transcripts, there were often discrepancies in statements suggesting a willingness to take PrEP, while others indicated no intent to engage in PrEP services (Table 3). Several reasons were mentioned for low perceived risk, specifically their frequent utilization of other HIV prevention strategies, such as condom use and HIV testing. Also, many reported that they engaged in serial monogamous relationships, and that they practiced inconsistent condom use because they were aware of their partner's status and risk. Taking a pill every day to prevent HIV infection when their perceived overall risk was low was deemed as a “drastic step.”

Table 3.

Example of Discrepancies in Reported Willingness to Take Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)

| Participant ID | Discrepant quotes | PrEP willingness quotes |

|---|---|---|

| CP106 | “Right now, no because I do not want…I just—and now, see here is the thing, I just, I do not know. I do not like swallowing pills.” | “It is like I really need this pill, because I would be seeing these fine boys. I just don't be thinking about it all of the time. I am just—I need to get on it for real.” |

| CP101 | “For me personally, I can't take it…So, for me, I have to kind of stick to the other safe sex techniques like condoms.” | “Well, you know, I don't have mixed feelings. I feel really good about PrEP. I think it's going to be a really game-changing tool for people.” |

| CP124 | “I hate PrEP. I do. I feel like what PrEP jas done is it has given people…it's like a lot of people that are on PrEP are now saying, well, you got to do it to me raw. You can't use a condom because I'm on PrEP.” | “I would. I don't really hate the idea of PrEP, but I hate the mindset of the people that are using PrEP. I'll say it that way. I would be down to take PrEP.” |

| CP109 | “It could lead to cancer too, if your kidneys aren't…it's hard to process those types of medicines…hard to process most prescription medicines, that's what they don't tell you.” | “I would, yeah.” |

| CP102 | “I am not as sexually active, I have one sex partner. I am leaving it at that. We both know each other's statuses.” | “I would, if only I was—I would but I am really not that—I am with just one person.” |

PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

“One thing about me is I talk to each one of my partners. I'm getting ready to have with. Period. I actually want to know their status before we start and everything.”—CP104, 26 years old, MSM

“I feel like the only hindrance it has is the commitment of taking something every single day. I feel like a lot of people have problems with that…the actual act of doing something every single day is tedious…”—CP110, 18 years old, Heterosexual

“I am one of those people who does not like to take a pill, I do not like to take meds. I do not like to take aspirin. However, now I absolutely encourage people to do it. Honestly, I think that if I was not in a relationship—and single right now.”—CP108, 29 years old, Gay

“Most of them just feel as though they're invincible and getting on PrEP, while it's costly, it would take a certain level of maturity and understanding and sexual competence to really take something like the drug itself.”—CP116, 22 years old, Gay

“Depending, if I felt more at risk, probably. In my current state, I don't think that it's something that I'd worry about or something that I would take such drastic steps to prevent.”—CP110, 18 years old, Heterosexual

Discussion

The goal of this study was to explore individual, interpersonal, and contextual factors among YBMSM in the South that affect uptake of PrEP by conducting in-depth interviews grounded in the ANM Health Services Utilization Framework. Results highlighted the ever-present impact of intersectional stigma on uptake of highly effective, biomedical HIV prevention strategies; as well as the impacts of sexual silence in southern black communities and medical distrust. Strikingly, another prevailing, unique theme from this study highlights that even when PrEP awareness is high and attitudes are favorable among vulnerable populations, many see themselves at low risk of HIV and do not feel that they personally need to use PrEP.

By using a framework that evaluated individual, as well as interpersonal and contextual, factors that may influence uptake of PrEP, themes related to intersectional stigma were found to be prominent among participants as a barrier to sexual health in the black community. Intersectional stigma refers to the synergistic, mutually constitutive associations between social identities and inequities.24 Participants in this study had multiple identities that caused perceived inequities and stigma internally and interpersonally, which they felt was compounded by living in a southern community. Previously, black MSM in New York City reported that internalized homophobia was felt to lead to higher rates of condomless sex and affect acceptance of PrEP.25 Our study also found high levels of internalized and perceived homophobia among participants; however, our participants felt that the internal, perceived, and experienced stigma related to having sex with men was compounded not only by their black race but also by their gender and the state in which they lived. One participant eloquently described how his own homophobia kept him from being able to have sexual interactions with men without feeling intense shame. Many participants also expressed that being perceived as gay or a “sissy” (i.e., highly effeminate gay man) put their ability to be perceived as masculine in their black community at risk, which often led to strain in relationships with male family members. Masculinity is an often idealized social norm that has been found to shape beliefs as well as social practices among men and women in a community, and has been found to inhibit other HIV prevention strategies, such as HIV testing.26

Other themes found in our study included stigma related to PrEP and high levels of medical distrust. High levels of stigma related to PrEP were reported among participants, because it was felt that persons on PrEP were less likely to use condoms and were more sexually promiscuous. This has been described in the literature and found to be associated with low interest in PrEP use as well as high sexual-risk-taking behavior.27 In our study, a few participants even endorsed that starting PrEP would cause some in the community to think that they were actually infected with HIV. Medical distrust also caused a large number of participants to report concerns about use of PrEP directly leading to increased risk of acquiring HIV. Living in a state where the Tuskegee experiments were performed, many reported conspiracy theories regarding PrEP that they themselves or peers endorsed. The most profound belief that embodied the level of distrust among participants was the concern that long-acting injectable PrEP was a means for the government to infect members of the black community with HIV. These themes have been found in a number of studies with racial and gender minorities, but few studies have evaluated interventions to improve medical distrust among these communities.27,28

Themes of intersectional stigma were also felt to be related to a pervasive sexual silence in southern black communities. This idea of sexual silence at the community level has been described in other literature and in different populations.29,30 Many participants reported that black MSM are more at risk of HIV because they are not exposed to information on sexual health in their homes or communities until they are well into adulthood. It was perceived that there was a larger acceptance among white communities to discuss sexuality and HIV prevention strategies. This theme was exemplified by multiple stories of participants having family members infected with HIV or who died from AIDS-related illnesses with no discussion of HIV or HIV prevention strategies in their households. The role of sexual silence and women's decision making about protection in sexual encounters has been explored in the Southern United States, as well as concerns about losing close interpersonal relationships.29 Another study, focused on Hispanic culture, described how sexual silence in western societies like the United States led to higher rates of sexual abuse, rape, and lack of knowledge and access to protection.30 Many studies have also focused on the effect of sexual silence on the HIV epidemic in Arab, African, and Asian countries.31,32 Heading in to the fourth decade of the HIV epidemic, this work and others illustrate the need for more research that focuses on how to overcome the stigma, shame, and silence that is still fueling the global HIV epidemic, especially among highly vulnerable populations.

One of the most significant findings of this study was that while many participants were aware of PrEP and expressed openness to using PrEP, most were not PrEP users and reported an overall low personal perceived risk for contracting HIV. This is of high significance given findings among an MSM cohort that those who had higher concern for contracting HIV were more likely to access PrEP services than those with low concern, and that differences may exist among MSM from different racial as well as ethnic backgrounds.33 One participant's quote that PrEP may be a “drastic step” is the most illustrative of where most of these men feel PrEP currently fits among their day-to-day priorities. Also, our measurement of willingness to use PrEP was based on when participants were directly questioned. However, lending to the qualitative aspects of our research, we were able to decipher that while most reported openness, they often expressed their concerns about being on PrEP earlier in the interview, suggesting that they would not in actuality attempt to engage in PrEP services. Difficulty in understanding how to activate reported interests in PrEP services to actual access, uptake, and adherence is becoming the new challenge in HIV prevention research.34 Informed by research in other HIV areas, such as HIV testing, lessons can be learned to influence and guide research for PrEP. Just because a new HIV prevention modality is available, does not mean it will be used by at-risk populations and focusing on strategies to promote PrEP under the umbrella of sexual health more generally, rather than out of necessity for high-risk subpopulations, might help dampen some of the stigmas related to utilization of PrEP services by already highly stigmatized populations.35

This study has several limitations that must be noted. Recruitment for this study was aided by two community-based organizations that offer HIV prevention services. As such, the sample may be biased and reflect a subgroup of YBMSM who are more accustomed to discussing and accessing HIV prevention services. As an example, based on the ANM framework, the authors explored structural barriers, such as health insurance, as barriers to access of healthcare, which was found in a quantitative study studying young MSM.36 We felt this was especially necessary to explore, given the fact that Alabama is a non-Medicaid expansion state. However, only a few or our participants endorsed the notion that YBMSM may have less access to healthcare than their white counterparts, and that this in turn may be contributing to decreased uptake of PrEP. In addition, those with high levels of medical or research distrust may have been less likely to participate in the study, leading to a lack of representation of more marginalized members of the black community in our sample. Of note, this study did not evaluate healthcare providers' perceptions and overall willingness to prescribe PrEP, which may also serve as a major barrier to accessing PrEP, and it is the intention of the authors to investigate such structural factors in future research.37 Also, these 25 participants' views and beliefs may not adequately reflect the beliefs of other southern YBMSM. Finally, while we explored numerous facets of the ANM framework, we did not explore environmental factors within the healthcare system that may impact utilization of PrEP by YBMSM in the South, which we intend to evaluate in future research.

In conclusion, initiatives to increase uptake of PrEP among YBMSM in the US Deep South will need to be multi-factorial and tailored. These interviews revealed a high level of intersectional stigma in the black community, which serves as a barrier for many young men desiring to accept themselves and be accepted by their loved ones. These factors expressly hinder their ability to engage effectively with HIV prevention strategies. These individual-level factors are compounded by a perceived sexual silence in the black community with lack of open discourse on sexual health, high degrees of medical distrust, and low perceived risk among a vulnerable population that expresses openness to using PrEP, while reporting a lack of intent to seek services for this HIV biomedical prevention tool.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the staff of the University of Alabama at Birmingham's Research and Informatics Service Center for their valuable assistance with study recruitment, and especially thank Eddie Jackson and Tammy Thomas for conducting interviews. They also acknowledge AIDS Alabama and Birmingham AIDS Outreach for their help with development of key study materials and aid in recruitment. This study was funded by the University of Alabama at Birmingham's Center for AIDS Research P30 AI027767. L.E. is currently funded through NIH/NIMH 1K23MH112417-01.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2016; vol. 28, 2017. Available at: http://cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html (Last accessed May11, 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 2. Altman D, Aggleton P, Williams M, et al. . Men who have sex with men: Stigma and discrimination. Lancet 2012;380:439–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beyrer C, Baral SD, van Griensven F, et al. . Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. Lancet 2012;380:367–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Fact Sheet: HIV and AIDS Among Gay and Bisexual Men. 2011. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hic/group/msm (Last accessed May4, 2018)

- 5. Sullivan PS, Hamouda O, Delpech V, et al. . Reemergence of the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men in North America, Western Europe, and Australia, 1996–2005. Ann Epidemiol 2009;19:423–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in U.S. HIV Diagnoses, 2005–2014 Fact Sheet. Available at: https://cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/hiv-data-trends-fact-sheet-508.pdf (Last accessed May11, 2018)

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Fact Sheet: HIV Among Gay and Bisexual Men. 2015. Available at: https://cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/cdc-msm-508.pdf (Last accessed July5, 2018)

- 8. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Lifetime Risk of HIV Diagnosis in the United States. Available at: https://cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2016/croi-press-release-risk.html (Last accessed May11, 2018)

- 9. Grohskopf LA, Chillag KL, Gvetadze R, et al. . Randomized trial of clinical safety of daily oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate among HIV-uninfected men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;64:79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. . Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:2083–2090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murnane PM, Celum C, Mugo N, et al. . Efficacy of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention among high-risk heterosexuals: Subgroup analyses from a randomized trial. AIDS 2013;27:2155–2160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. . Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med 2012;367:423–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. . Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med 2012;367:411–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. . Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2587–2599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, et al. . Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:151ra125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bush S, Ng L, Magnuson D, Piontkowsky D, Mera Giler R. Significant uptake of Truvada for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization in the US in late 2014–1Q 2015. IAPAC Treatment, Prevention, and Adherence Conference; 2015:28–30 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Laufer FN, O'Connell DA, Feldman I, Zucker HA. Vital signs: Increased medicaid prescriptions for preexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection—New York, 2012–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:1296–1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elopre L, Kudroff K, Westfall AO, Overton ET, Mugavero MJ. Brief report: The right people, right places, and right practices: Disparities in PrEP access among African American men, women, and MSM in the deep South. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;74:56–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weinstein M, Yang OO, Cohen AC. Were we prepared for PrEP? Five years of implementation. AIDS 2017;31:2303–2305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J Health Soc Behav 1995;36:1–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Andersen R, Bozzette S, Shapiro M, et al. . Access of vulnerable groups to antiretroviral therapy among persons in care for HIV disease in the United States. HCSUS Consortium. HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. Health Serv Res 2000;35:389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc 1973;51:95–124 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saldana J. An introduction to codes and coding. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: Sage, 2009:1–31 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Simien EM. Doing intersectionality research: From conceptual issues to practical examples. Politics Gender 2007;3:264–271 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jonathan G, Caroline P, Richard GP, Patrick AW, Morgan P, Jennifer SH. Psychosocial implications of homophobia and HIV stigma in social support networks: Insights for high-impact HIV prevention among black men who have sex with men. Health Educ Behav 2015;43:217–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Seeley J, Watts CH, Kippax S, Russell S, Heise L, Whiteside A. Addressing the structural drivers of HIV: A luxury or necessity for programmes? J Int AIDS Soc 2012;15:17397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Price D, Finneran S, Allen A, Maksut J. Stigma and conspiracy beliefs related to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and interest in using PrEP among black and white men and transgender women who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 2017;21:1236–1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cahill S, Taylor SW, Elsesser SA, Mena L, Hickson D, Mayer KH. Stigma, medical mistrust, and perceived racism may affect PrEP awareness and uptake in black compared to white gay and bisexual men in Jackson, Mississippi and Boston, Massachusetts. AIDS Care 2017;29:1351–1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Konkle-Parker D, Fouquier K, Portz K, et al. . Women's decision-making about self-protection during sexual activity in the deep south of the USA: A grounded theory study. Cult Health Sex 2018;20:84–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marín BV. HIV prevention in the Hispanic community: Sex, culture, and empowerment. J Transcult Nurs 2003;14:186–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Duffy L. Suffering, shame, and silence: The stigma of HIV/AIDS. J Assoc Nurs AIDS Care 2005;16:13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gańczak M, Barss P, Alfaresi F, Almazrouei S, Muraddad A, Al-Maskari F. Break the silence: HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitudes, and educational needs among Arab university students in United Arab Emirates. J Adolesc Health 2007;40:572.e1–572.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Holloway IW, Tan D, Gildner JL, et al. . Facilitators and barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis willingness among young men who have sex with men who use geosocial networking applications in California. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017;31:517–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rolle C-P, Rosenberg ES, Siegler AJ, et al. . Challenges in translating PrEP interest into uptake in an observational study of young black MSM. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;76:250–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Frye V, Wilton L, Hirshfield S, et al. . “Just because it's out there, people aren't going to use it.” HIV self-testing among young, black MSM, and transgender women. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2015;29:617–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marks SJ, Merchant RC, Clark MA, et al. . Potential healthcare insurance and provider barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis utilization among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017;31:470–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mullins TLK, Zimet G, Lally M, et al. . HIV care providers' intentions to prescribe and actual prescription of pre-exposure prophylaxis to at-risk adolescents and adults. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017;31:504–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]