Myocarditis has been described as a feature of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC)1, 2. We report a case of a young male with acute myocarditis as the first presentation of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (AC).

A 24-year-old male was hospitalized with acute left precordial chest pain, diaphoresis, dyspnea and lightheadedness. He had mild upper respiratory symptoms for a few days prior to the hospitalization. He had no cardiac history. He was a competitive mountain biker.

His family history was significant for aborted sudden death in his father 7 years ago. While it was initially attributed to a pneumonia, it was later investigated by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) that was interpreted as normal, followed by genetic testing for Brugada syndrome, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, and long QT syndrome, which was unrevealing. Due to the uncertainty regarding the cause of the aborted sudden death, the father had received an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). He had had no ICD therapies.

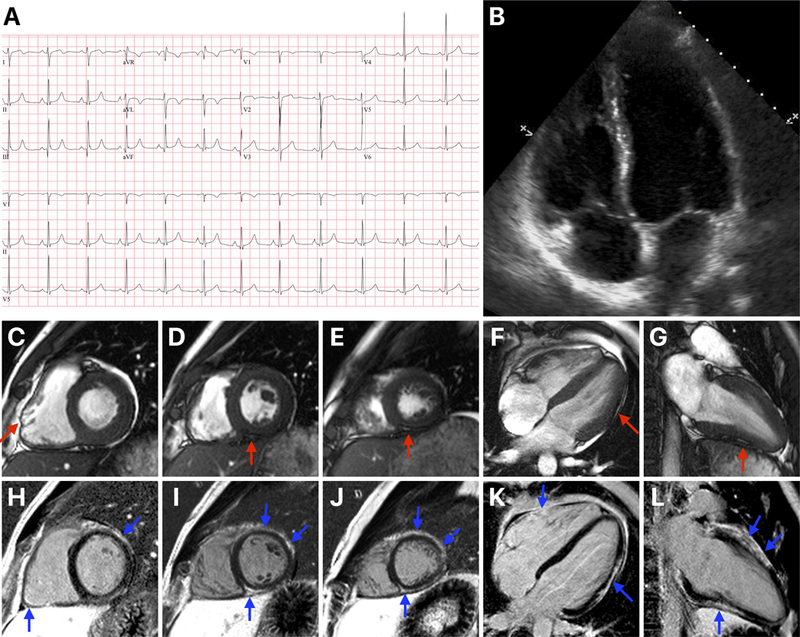

The patient’s electrocardiogram was unremarkable (Figure 1). The C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and D-dimer were normal. His troponin I was elevated at 7.05 ng/mL (normal <0.028 ng/mL) peaking at 16.25 ng/mL. An echocardiogram revealed normal left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction of 65% (Figure 1), but with hypokinesis of the mid and apical lateral segments. This led to coronary angiography, which demonstrated normal coronary arteries. He was presumptively diagnosed with acute viral myocarditis.

Figure 1.

Panel A shows the 12-lead electrocardiogram. Panel B shows a 4-chamber view of the echocardiogram showing normal left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) sizes. Panels C through G are systolic cine cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) images (C – basal short axis, D – mid short axis, E – apical short axis, F – 4-chamber long axis and G – 2-chamber long axis views) showing normal LV and RV sizes. The red arrow in C points to an area of regional dyskinesis in the RV free wall. The red arrows in D through G point at areas of fatty replacement within the LV myocardium. Panels H through L are end-diastolic late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) CMR images in the same views as the cine images. The blue arrows point at the multiple areas of fibrofatty replacement involving the anterior, lateral and inferior LV segments, and the basal inferior RV free wall. This pattern of LGE is typical for arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy.

To confirm the diagnosis, he had a CMR that showed normal LV and RV sizes and function (Figure 1). However, there was epicardial and mid-myocardial late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in several LV and basal inferior RV segments. Tissue characterization by cine and T1-weighted imaging demonstrated that some of these areas represented fatty replacement (Figure 1). A Holter monitor showed rare ventricular ectopic beats (82 in 24 hours) but no ventricular tachycardia. Overall, he did not meet the 2010 Task Force Criteria for the Diagnosis of ARVC.

Based on the LGE pattern suggestive of AC1, the fatty replacement, and the family history, the patient was referred for genetic testing. The patient was screened for variants in 7 AC genes (RYR2, TMEM43, DSP, PKP2, DSG2, DSC2, and JUP). A novel heterozygous variant was identified in exon 23 of the DSP gene – c.3415_3417delTATinsG. The variant causes a shift in reading frame starting at codon Tyrosine 1139, changing it to a Glycine, and creating a premature stop codon at position 10 of the new reading frame, denoted p.Tyr1139GlyfsX10. It is expected to result in either an abnormal truncated protein product or loss of protein from this allele through nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Other frameshift variants in the DSP gene have been reported in association with DSP-related disorders, including AC. The variant was not found in the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD)3. Based on these data and segregation analysis, the variant was classified as pathogenic. Based on the characteristic LGE pattern, the myocardial fatty replacement, and the pathogenic variant in the DSP gene, the patient was diagnosed with AC.

The patient’s father was found to carry the same DSP variant; AC was likely the cause of his aborted sudden death 7 years ago. His two siblings were tested next. A 22-year-old collegiate athlete brother was found to have the same DSP variant. CMR showed extensive epicardial and mid-myocardial LV LGE with an ejection fraction of 49% and an unremarkable RV. The other sibling, a 26-year-old brother, did not carry the variant. After arrhythmic risk stratification, the patient and his affected brother received ICDs.

Bauce et al. first described clinical myocarditis in 2 siblings with familial ARVC secondary to a variant in the DSP gene4. Of 42 patients with left-dominant AC described by Sen-Chowdhry et al., 4 had a history of myocarditis1. Lopez-Ayala et al. described 7 patients with myocarditis – 2 with ARVC, 4 with left-dominant AC and 1 was a gene-positive, phenotype-negative daughter of a patient with left-dominant AC2. Myocarditis was the first clinical presentation in 6 of the 7 cases. Five patients carried variants in the DSP gene while 2 carried variants in the LDB3 gene.

The pathophysiology underlying inflammation in AC is not well understood. Sen-Chowdhry et al. postulated that inflammatory myocarditis is part of the natural history of AC, where it has a genetic rather than an infective basis1. Disease progression is purported to occur through episodes of myocarditis, involving cardiomyocyte loss followed by repair and replacement by fibrofatty tissue1. Most recently, antibodies to desmoglein-2 (DSG2) have been suggested as a possible explanation5.

In conclusion, myocarditis can be the initial presentation of AC. Since most myocarditis presentations of AC occur with left-dominant AC, the 2010 Task Force Criteria for the Diagnosis of ARVC are not reliable in these patients. CMR and genetic testing are key for their evaluation.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References:

- 1.Sen-Chowdhry S, et al. Left-dominant arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy: an under-recognized clinical entity. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:2175–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopez-Ayala JM, et al. Genetics of myocarditis in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:766–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lek M, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016;536:285–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauce B, et al. Clinical profile of four families with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy caused by dominant desmoplakin mutations. Eur Heart J 2005;26:1666–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatterjee D, et al. An autoantibody identifies arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and participates in its pathogenesis. Eur Heart J 2018. September 17. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy567. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]