Abstract

Introduction:

Microsporidia have been increasingly reported to infect humans. The most common presentation of microsporidia infection is chronic diarrhea which can be extremely debilitating and carries a significant mortality risk in immune compromised patients. Albendazole, which inhibits tubulin, and fumagillin, which inhibits methionine aminopeptidase type 2 (MetAP2), are currently the two main therapeutic agents used for microsporidiosis treatment. In addition, to their role as emerging pathogens in humans, the Microsporidia are important pathogens in commercially important insects, aquaculture, and veterinary medicine. New therapeutic targets and therapies have become a recent focus of attention for medicine, veterinary and agricultural use.

Areas covered:

Herein, we discuss the detection and symptoms of microsporidiosis in humans and the therapeutic targets that have been utilized for the design of new drugs for the treatment of this infection, including Triosephosphate isomerase (TIM), Tubulin, Methionine aminopeptidase 2 (MetAP2), Topoisomerase IV, Chitin synthases, and Polyamines.

Expert opinion:

Enterocytozoon bieneusi is the most common microsporidia in human infection. Fumagillin has a broader anti-microsporidian activity than albendazole and is active against both Ent. bieneusi and Encephaliozoonidae. Microsporidia lack methionine aminopeptidase type 1 (MetAP1) and are, therefore, dependent on MetAP2, while mammalian cells have both enzymes. Thus, MetAP2 is an essential enzyme in the Microsporidia and new inhibitors of this pathway have significant promise as therapeutic agents.

Keywords: Microsporidia, Microsporidiosis, Therapeutic targets, Diagnosis, Triosephosphate isomerase, Tubulin, Methionine aminopeptidase 2, Chitin synthases, Polyamines

1. Introduction

Microsporidia are unicellular, obligate intracellular parasites. They have a wide infection range from invertebrate to vertebrate hosts. Phylogenetic studies suggest that microsporidia are related to the Fungi 1–3 probably as a sister group along with the Cryptomycota. Microsporidia were first identified in the 19th century when Nosema bombycis was identified as the cause of pebrine disease in Bombyx mori which almost destroyed the European silkworm industry 4. Microsporidia are still responsible for economic losses due to their adverse effects on farming and other industries 5, 6. There are over 200 genera and 1400 species of microsporidia. While they are extremely diverse, they all contain a unique invasion apparatus the polar tube and are surrounded by a spore wall 7. The spore wall contains two layers, the exospore layer, and a chitin-containing endospore layer 8–10. Chitin is probably essential in maintaining spore rigidity and function. The polar tube is a highly specialized invasion organelle, which is coiled around the sporoplasm inside of spore before germination and invasion. Upon appropriate environmental stimulation, the polar tube extrudes out of spore rapidly and polar tube proteins interact with host cell surface proteins creating an invasion synapse, the sporoplasm and nucleus travel down the hollow polar tube and enter the host cells in this invasion synapse 11–14. The sporoplasm then undergoes its life cycle which consists of a proliferative phase (merogony), spore production phase (sporogony), and formation of mature spores (infective phase), either in a parasitophorous vacuole or in the host cytoplasm depending on the species of microsporidia 15, 16.

Microsporidiosis has been recognized as a significant problem for immune deficient patients including those with AIDS, organ transplantation, bone marrow transplantation, those with neoplastic disease on chemotherapy, those receiving immunomodulatory therapy for collagen vascular diseases, and is being increasingly recognized in the elderly and pediatric population 17, 18. Most of microsporidia infections are thought to result from oral infection due to contaminated water and food containing microsporidian spores and the site of initial infection is the gastrointestinal tract 19. However, other transmission routes including direct contact through broken skin, the eye, and genital mucosa have been reported 19. Microsporidia infections in humans can cause gastrointestinal, brain, kidney, liver, eye, muscle, sinus, respiratory, or disseminated infections. Infection in immune competent mammals are often chronic and asymptomatic, while immune compromised hosts often develop lethal infections 20. Diarrhea and chronic wasting associated with microsporidia infection in AIDS patients has been widely reported, with microsporidia being detected in some studies in 70% AIDS patients with chronic diarrhea without other known causes21–23.

Since the first description of human infection with microsporidia causing encephalitis in 1959, there have been an increasing number of species of microsporidia recognized in human infections which are summarized in Table 1. Microsporidia seen in human infection include: Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Encephalitozoon intestinalis, Encephalitozoon cuniculi, Encephalitozoon hellem, Anncaliia algerae, Anncaliia connori, Anncaliia vesicularum, Microsporidium sp., Nosema ocularum, Pleistophora ronneafiei, Trachipleistophora sp., Tubulinosema acridophagus and Vittaforma corneae 2, 24–26. Enterocytozoon and Encephalitozoon are the most common genera causing human infections. Ent. bieneusi was the first microsporidia reported causing diarrhea in patients with AIDS 6. Ent. bieneusi has not been cultivated continuously in vitro and there are no reliable rodent models of this infection, limiting its use for studies of immune responses and for drug screening 27. Enc. intestinalis was first identified in AIDS patients with diarrhea and is considered the second-most prevalent species reported to infect humans 28, 29. Enc. cuniculi was the first mammalian microsporidian species that was isolated and successfully grown in long-term culture 30. Enc. hellem was first identified from conjunctival specimens of AIDS patients and can cause systemic infections in humans 31–33. All three Encephalitozoon species infecting humans have been successfully grown in tissue culture and there are rodent models of all three of these organisms.

TABLE 1.

Species of microsporidia infecting humans

| Species | Synonym(s) | Common sites of infection in humans |

Other mammalian hosts |

Reported Non-mammalian hosts |

Disease Manifestations Reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anncaliiaalgerae |

Brachiola algerae |

Eye | Mosquitoes | myositis, keratoconjunctivitis, cellulitis |

|

| Nosema algerae | Muscle | ||||

| Anncaliia connori | Brachiola connori | Systemic | disseminated disease | ||

|

Nosema connori | |||||

| Anncaliia vesicularum | Brachiola vesicularum | Muscle | myositis | ||

| Encephalitozoon cuniculi | Nosema cuniculi | Systemic | Wide host range | Birds | hepatitis, encephalitis, peritonitis, urethritis, prostatitis, nephritis, sinusitis, keratoconjunctivitis, cystitis, diarrhea, disseminated infection |

| Encephalitozoon hellem | Eyes | Bats | Birds | superficial keratoconjunctivitis, sinusitis, pneumonitis, nephritis, protatitis, urethritits, cystitits, diarreha, disseminated infection | |

| Encephalitozoon intestinalis | Septata intestinalis | Small intestine | Wide host range | Geese | diarrhea, intestinal perforation,, cholangitis, nephritis, superficial keratoconjunctivitis, disseminated infection |

| Enterocytozoon bieneusi | Small intestine | Wide host range | Birds | diarrhea, malabsorption with wasting syndrome, cholangitis, rhinitis, bronchitis | |

| Biliary tract | |||||

| Microsporidium africanum | Eyes | stromal keratitis | |||

| Microsporidium ceylonensis | Eyes | stromal keratitis | |||

| Microsporium CU (Endoreticulatus-like) | Muscle | myositis | |||

| Nosema ocularum | Eyes | stromal keratitis | |||

| Pleistophora ronneafiei | Muscle | Fish* | myositis | ||

| Trachipleistophora anthropopthera | Eyes | Insects* | encephalitis, keratitis, disseminated infection | ||

| Systemic | |||||

| Trachipleistophora hominis | Eyes | Mosquitoes* | myositis, keratoconjunctivitis, sinusitis, encephalitis | ||

| Muscle | |||||

| Tubulinosema acridophagus | Muscle | Fruit fly* | myositis, disseminated infection | ||

| Systemic | |||||

| Vittaforma corneae | Nosema corneum | Eyes | Keratoconjunctivitis, urinary tract infection | ||

| Urinary tract |

Putative host(s) based on phylogeny or host relationships of other species within the genus.

Other species of microsporidia have been reported less frequency in human infections. V. corneae was first identified in a non-HIV-infected individual and has been reported to cause keratitis 34, 35. A. algerae was found in mosquitoes and other insects and has caused myositis in immune deficient humans 27, 36, 37. The natural hosts of Trachipleistophora sp. (T. hominis and T. anthropopthera) are insects, and these pathogens have caused brain infections, myositis and keratitis in immune deficient patients 38. All of these microsporidia have been successfully grown in tissue culture and there laboratory animal models of infection with these organisms.

2. Clinical presentations of microsporidiosis in humans

2.1. Gastrointestinal infection

Most microsporidian infections are transmitted by oral ingestion of spores in spore-contaminated water or food leading to initial infection of the gastrointestinal tract. Symptomatic infection of the epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract can cause chronic diarrhea and wasting in patients, which is the most common presentation of microsporidiosis in both immune competent and immune deficient patients. Most of these infections are caused by either Ent. bieneusi or one of the Encephalitozoonidae (e.g. Enc. intestinalis) 15, 39–41. Ent. bieneusi has been identified as causing diarrhea in travelers, children, the elderly, and patients with AIDS, organ transplantation or other immune deficiency 42–44. Other gastrointestinal manifestations of microsporidiosis include hepatitis, peritonitis, and biliary disease with sclerosing cholangitis 33, 45, 46.

2.2. Central Nervous System Infection

Enc. cuniculi in mammals is known to cause granulomatous encephalitis. Spores consistent with Encephalitozoon spp. were found in the cerebrospinal fluid from a child with serological evidence of Enc. cuniculi infection 47. In immune compromised patients, Enc. cuniculi has presented as a mass lesion with associated seizures and focal neurological deficits. Trachipleistophora anthropopthers has also been reported to cause cerebral disease 48, 49. Two patients with AIDS who died from disseminated T. anthropopthers infections had central nervous system involvement with multiple ringlike lesions on computed tomography scanning 49.

2.3. Ocular Infection

Microsporidian keratoconjuctivitis is often due to infection by the Encephalitozoonidae with the majority of infections being due to Enc. hellem 50–52. Most of these infections occur in the patients of immune dysfunction like HIV patients, however, there are case reports of superficial epithelial keratitis caused by Encephalitozoon spp. in immune competent patients. Most of these infections of immune competent patients were in contact lens wearers 15. Seasonal keratoconjunctivitis due to Vittaforma corenea has been reported in South East Asia, and associated with water or soil exposure.

2.4. Musculoskeletal Infection

Myositis has been reported due to infection with A. algerae, Anncaliia vesicularum, Tubulinosema spp., Endoreticulatus spp., Pleistophora sp., Trachipleistophora hominis, and Pleistophora ronneafiei. Trachipleistophora hominis and Trachipleistophora anthropopthera musculoskeletal infection has been reported in patients with AIDS 48. A Tubulinosema species was identified in two cases of myositis and disseminated microsporidiosis in immunosuppressed human patients 53, 54. P. ronneafiei, a genus which was originally identified from fish muscle, was found in a muscle biopsy from an HIV-negative patient and identified as the cause of myositis in AIDS patients 55, 56. A. algerae has been identified as the cause of myositis in immune deficient patients with organ transplants and in a patient with vocal cord lesions 36, 37, 57. Anncaliia connori caused disseminated infection including myositis in a child with SCID and Anncaliia vesicularum myositis in a patient with AIDS 57, 58.

2.5. Genitourinary Tract Infection

In mammals, infection of the genitourinary system with spores being seen in the urine is commonly seen with Encephalitozoonidae, T. anthropophthera and V. cornea 49, 59–61. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis composed of plasma cells and lymphocytes is the most frequent pathologic finding in humans with genitourinary microsporidiosis 44, 62, 63. Congenital transmission of human infection with microsporidia has not been reported, although this has been seen in other mammals.

2.6. Other infections

A. algerae has been reported as a cause of cellulitis in a child with leukemia 64. Encephalitozoon sp. have been reported to cause nodular skin lesions 65. Sinus and respiratory infections have been reported due to Encephalitozoonidae. In the cases of keratoconjunctivitis, due to Enc. hellem, spores were found in samples of patients’ sputum indicating a co-existent respiratory infection 66.

3. Diagnosis of Microsporidiosis

There are now at least ten Microsporidian genera that have been identified in human infections 40, 67, 68. Light microscopy is useful in the identification of microsporidian spores in various tissue samples and fluids. Stains such as chromotrope 2R, calcofluor white (fluorescent brightener 28), and Uvitex 2B 69–71, have been useful in the identification of spores in stool specimens and other body fluids. However, these techniques cannot provide species-specific diagnosis. Electron microscopy or molecular techniques can be used to identify the exact species of microsporidia causing an infection 72. In cases of gastrointestinal infection, it is useful to also urine specimens for spores, as shedding of spores in the urine is common in infections due to Encephalitozoonidae, but not in infection by Ent. bieneusi.

3.1. Light and Immunofluorescent Microscopy

Spores are the main targets for clinical diagnosis. Due to the small size of microsporidian spores (1~5 um) adequate magnification using a 60X to 100X objective is required for their detection. Spores in fresh tissue samples are usually birefringent and retractile and can be seen using a phase-contrast microscopy 15. The detection of spores in stool is difficult due to the presence of bacteria and yeast 73–75. In order to increase the specificity and sensitivity of detecting microsporidia, selective staining methods (calcofluor white, chromotrope 2R, Uvitex 2B, Warthin-Starry silver stain, Giemsa, acid-fast, and Brown-Hopps Gram) should be employed 39, 40, 76, 77. Antibodies for IFA techniques have been reported and, if available, can increase the sensitivity of this examination and provide species identification 15.

3.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) is the gold standard technique for the identification of microsporidian species due to its ability to identify the polar tube and other phylum- and species-specific ultrastructural characters 40, 78. However, it is expensive, time-consuming and requires specialized equipment that is not available in most laboratories 79.

3.3. Nucleic Acid-based Molecular Techniques

Nucleic acid-based diagnosis techniques have proven useful in the diagnosis of microsporidiosis 80. Molecular methods, such as PCR, can provide species and genotype diagnostic information 80–83. The genomes of most of the microsporidia that infect humans are available on MicrosporidiaDB (http://microsporidiadb.org/micro/) and primers for the diagnosis and speciation of these organisms based on rRNA genes 84 have been evaluated in many clinical and field settings 80–83. Nucleic acids can be isolated from clinical specimens such as urine or stool, in vitro cultures, and paraffin-embedded material by commercial DNA extraction kits. Real-time PCR assays have been developed and may provide higher sensitivity and specificity than traditional PCR 85 with detection limits of 102 to 103 spores/ml in stool 86, 87. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH)-based techniques using probes against microsporidia small subunit (SSU) rRNA have also been used for the detection of Ent. bieneusi and Enc. hellem 88–90; however, FISH is less sensitive than PCR due to the lack of signal amplification 80.

3.4. Serology

Serological techniques that have been reported for the detection of immune responses, both IgG and IgM, to microsporidiosis include: immunoblotting (IB), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), indirect immunofluorescence test (IFAT), counter-immunoelectrophoresis (CIE), and carbon immunoassay (CIA) 91–97. IFAT and ELISA are the most widely used tests and they correlate well with each other 98. A limitation of serology is that it is difficult to distinguish when the infection has occurred as antibodies persist in the host for a long time following infection 99, 100. To this end, the utility of serology is not as good as molecular diagnostic methods 80. However, serology can be used for epidemiology to examine infection prevalence and will identify that an animal has been infected 101, 102. Serological screening is used in laboratory research to eliminate potentially infected animals, particularly rabbits with Enc. cuniculi infection, to avoid infection related confounding effects on experimental results 103.

4. Therapeutic targets for the treatment of microsporidiosis

4.1. Triosephosphate isomerase (TIM)

The genome of most microsporidia are highly reduced and their genome size is reported to be among the smallest of eukaryotic organisms 104. In addition, microsporidia do not have typical mitochondria, but possess mitosomes, a mitochondrial remnant which cannot perform oxidative phosphorylation and microsporidia lack the tricarboxylic acid cycle 105–107. This requires microsporidia to rely on other metabolic pathways such as the glycolytic pathway, pentose phosphate pathway, and trehalose metabolism for energy 108. Thus, the enzymes involved in these pathways, which are critical for the microsporidia, are potential therapeutic drug targets.

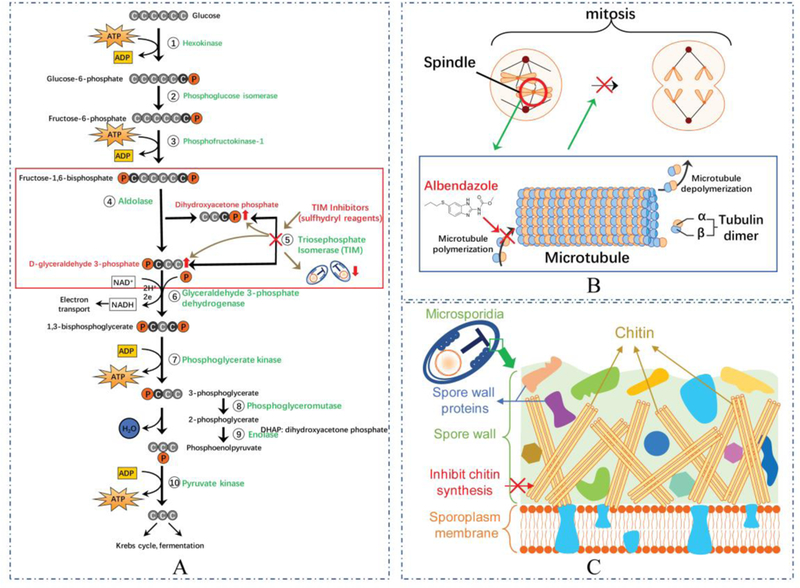

Triosephosphate isomerase (TIM), which plays an important role in glycolysis of Enc. intestinalis, was analyzed as a drug target for the therapy of microsporidiosis 109. TIM catalyzes the reversible interconversion of the triose phosphate isomers dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and D-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAP), and is essential for efficient energy production. Studies of TIM in Trypanosoma cruzi, T. brucei, Entamoeba histolytica, and Giardia duodenalis have demonstrated that modification of cysteine (Cys) residues by sulfhydryl reagents could change its function and structure, leading to inactivation of this enzyme 110–113. As a proof of concept, three sulfhydryl reagents (MMTS, MTSES, and DTNB) were used to modify the conserved Cys in Enc instestinalis TIM (EiTIM). These three sulfhydryl reagents do not inactivate human triosephosphate isomerase (HsTIM) despite 109, 114. Treatment with these compounds caused a significant reduction of EiTIM activity in a concentration-dependent manner. When EiTIM was inhibited the process of interconversion between DHAP and GAP was reduced, leading to an accumulation of either DHAP or GAP which are both toxic to the microsporidia spores (Figure 1A). A microsporidia lack the glyoxalase system, which can detoxify these compounds, the toxicity of TIM inhibition may be enhanced in microsporidia. Furthermore, three compounds that are widely used in the pharmaceutical industry (omeprazole, rabeprazole, and sulbutiamine) have also been demonstrated to modify EiTIM Cys residues and to significantly inactive EiTIM [98], providing lead compounds for the development of this therapeutic pathway. Overall, these data suggest Triosephosphate isomerase is a potential target for new therapeutic agents for microsporidiosis.

Figure 1. Therapeutic targets of microsporidia and the mode of action of their drugs.

(A) Sulfhydryl reagents can inhibit Triosephosphate Isomerase (TIM) in microsporidia reducing the interconversion of dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and D-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAP) leading to an accumulation of either DHAP or GAP which are toxic to microsporidia resulting in the death of this organism. (B) Albendazole inhibits the polymerization of tubulin, resulting in the failure formation of microtubules, which can lead to an inability to form spindle fibers during the mitosis, and cell death. (C) Chitinase inhibitors, such as nikkomycins and polyoxins, act as competitive inhibitors for chitin synthesis inhibiting the synthesis of chitin from UDP-N-acetylglucosamine resulting in cell damage in both mature and immature spores of microsporidia. Images were created using Motifolio Anatomy Drawing Toolkit available from http://www.motifolio.com/anatomy.html.

4.2. Tubulin

Microtubules are a characteristic feature of eukaryotic cells and critical in the formation of the mitotic spindle, cytoskeleton, flagella, and cilia. Microtubules are formed by polymerization of tubulin which is a dimeric protein composed of α-tubulin and β-tubulin (Figure 1B) 115. Benzimidazoles are a heterocyclic aromatic organic compound which consists of the fusion of benzene and imidazole. These drugs are inhibitors of microtubule polymerization by binding to tubulin and disturbing the self-association of tubulin subunit 116, 117. The benzimidazoles include: albendazole, cambendazole, benomyl, carbendazim, fenbendazole, mebendazole, and triclabendazole. These compounds have diverse biological activity and applications including antifungal, anticancer, antihelminthic, antiviral, anti-histaminic, anti-inflammatory, anticoagulant properties and antihypertensive effects 118,119. They have been used since the 1960s as antihelminthic agents in veterinary and human medicine, and as antifungal agents in agriculture 115, 120–124.

Benzimidazoles are also the most widely used drugs in the treatment of microsporidiosis. The only clear microtubules detected in microsporidia are intranuclear spindle microtubules formed during nuclear division 41, 125, 126. Analysis of the microsporidia β-tubulin sequence identified similar amino acid residues that are present in various microsporidia (Encephalitozoonidae and A. algerae) which are associated with benzimidazole sensitivity and are consistent with the clinical response of these particular microsporidian infections to albendazole. For example, Val 268 has been identified in nearly all benzimidazole sensitive organisms, is present in these microsporidia, and is believed to play the role in benzimidazole activity 115, 120. However, several other microsporidia, e.g. Ent. bieneusi and V. corneae, have a β-tubulin sequence with residues associated with benzimidazole resistance, and these microsporidia have been found not to response to albendazole.

Albendazole is highly active against all of the Encephaliozoonidae including Enc. hellem, Enc. cuniculi, and Enc. intestinalis in vitro 127. Patients with Enc. intestinalis diarrhea improved with albendazole treatment which is consistent with the analysis of β-tubulin of this organism 128. Proliferative stages of microsporidia in albendazole treated individuals appeared larger than usual and unable to undergo cell division, probably due to the interaction of albendazole with tubulin resulting in the failure of these treated organisms to form spindle fibers and undergo mitosis (Figure 1B) 129. Furthermore, not only albendazole but the metabolized albendazole sulfoxide and other benzimidazole derivatives inhibited the growth of Enc. intestinalis in vitro 124.

A patient with disseminated microsporidiosis with advanced renal failure due to Enc. cuniculi infection was treated with albendazole, which resulted in improvement in serum creatinine levels, complete disappearance of spores from sputum, and a negative urine culture 130. Albendazole also appears to have an attenuating effect on A. algerae infection in Rabbit Kidney (RK13) cells and long-term treatment could inhibit up to 98% of spore production 131.

In contrast, several studies using albendazole as a treatment for Ent. bieneusi, have found that it is less sensitive to this drug compared with the Encephaliozoonidae 6, 132. As has been seen in other organisms, resistance has been demonstrated in diverse species including microsporidia 133. Benzimidazole derivatives have resistance in helminths is an active area of study and such compounds or new tubulin binding drugs could be useful in the treatment of microsporidiosis.

4.3. Methionine aminopeptidase 2 (MetAP2)

Methionine aminopeptidase (MetAPs) activity is essential for eukaryotic cell survival as the removal of the terminal methionine of a protein is often critical for its function and posttranslational modification. Two major classes of Methionine aminopeptidases, designated type 1 and type 2 (MetAP1 and MetAP2), were originally identified as cytosolic proteins in eukaryotes 134–136. In the genome of the cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp., a novel MetAP3 gene was also identified 137. MetAP2, as a member of the dimetallohydrolase family, is a cytosolic metalloenzyme that catalyzes the hydrolytic removal of N-terminal methionine residues from nascent proteins 138–140. Important functions of this enzyme, which is found in all organisms, are its role in tissue repair and protein degradation, as well as the role it plays in angiogenesis 139, 141. The MetAP2 genes were identified from the human pathogenic microsporidia Enc. intestinalis, Enc. hellem, Enc. cuniculi, Ent. bieneusi, and A. algerae using the strategy of homology polymerase chain reaction 142–144. And based on genome sequence data (Microsporidiadb.org) the microsporidia appear to only contain MetAP2 145. Since both MetAP1 and MetAP2 genes exist in mammalian genomes and the functions of these two MetAP genes overlap, this makes microsporidia MetAP2 an essential gene in microsporidia and a logical target for designing therapeutic agents for microsporidiosis 144.

MetAP2 is the target of two groups of anti-angiogenic natural products, ovalicin and fumagillin, and their analogs 146, 147. Fumagillin together with albendazole are two most widely used therapeutic agents for microsporidiosis, however, albendazole is not active against Ent. bieneusi 41, 115, 132. Fumagillin, ovalicin, and their analogs like TNP-470, have been demonstrated to have anti-microsporidial activity in vitro and in vivo in animal models and clinical cases of microsporidiosis, including activity in patients with Ent. bieneusi infection 148–151. Fumagillin also works in the treatment of Nosema apis and Pleistopbora anguillarum in bees and fish 152–154.

Study of MetAPs in yeasts revealed that Saccharomyces cerevisiae deficient in MetAP1 could be killed by treatment with fumagillin or ovalicin, however, yeast deficient in MetAP2 were not killed by those drugs 146, 155. This confirmed that MetAP2, but not MetAP1 is the target of fumagillin. The activity of fumagillin is due to its ability to bind to MetAP2 via an epoxide ring that is the site of covalent binding to a histidine residue in the active site of MetAP2 146, 155. Structure analysis of MetAP2 demonstrated that His231 in human MetAP2 is the residue that fumagillin forms a covalent bond with, and this residue is also highly conserved in microsporidian MetAP2 sequences 142, 156. Fumagillin treatment of microsporidia causes lipid and protein granules in host cell cytoplasm to increase suggesting effects on lipid incorporation into membranes 157. Ultrastructure demonstrated that the shape of proliferative forms became distorted, membranous organelles were misshapen with numerous convoluted vacuoles, depletion or scattering of ribosomes, and breaking of parasite’s plasma membranes 41. Even though human MetAP1 is not inhibited by fumagillin, there is inhibition of human MetAP2, and fumagillin and its analogs caused thrombocytopenia in patients treated with fumagillin 150. Although this side effect did not limit treatment, improved and more selective microsporidian MetAP2 inhibitors would be useful, as well as compounds that lacked epoxide rings and were competitive inhibitors of MetAP2. There is a significant amount of interest by pharmaceutical companies in MetAP2 inhibitors due to their ability to affect to angiogenesis, which has resulted in a pipeline of new compounds that could be evaluated for their activity against microsporidia.

4.4. Synthetic Polyamines

Polyamines are low molecular weight organic compounds having more than two amino groups. Natural polyamines are found in all forms of life. These small molecules are commonly known as putrescine (diamine), spermidine (triamine), and spermine (tetramine) and they can bind to DNA, chromatin and RNA affecting nuclear and cell division 158. Ribosomes of the microsporidia contain polyamines (mainly spermine and spermidine), and these polyamines bind to rRNA helping to maintain the compact structure of the ribosome 159. Polyamine concentrations in cells are carefully controlled by synthesis, degradation, excretion, and uptake from the environment 160. In mammals and many protozoa, synthesis occurs from the conversion of ornithine to putrescine through ornithine decarboxylase (ODC). Spermidine and spermine are formed from putrescine by adding one or two amino-propyl groups using ODC and S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase (AdoMetdc) as rate limiting enzymes 161, 162. The key enzymes in interconverting of spermine and spermidine to spermidine and putrescine respectively, are spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase (SSAT) and polyamine oxidase (PAO) 160. The trio of ODC, AdoMetdc and SSAT serves to keep intracellular polyamines at relatively stable levels 161. Research using purified ribosomes has demonstrated that they exchange polyamines with polyamines in the media suggesting that polyamine binding is a dynamic process in the ribosome 163. Taking up exogenous polyamine analogs has been shown to down-regulate ODC and AdoMetdc, and up-regulate SSAT, leading to a down-regulation of polyamine synthesis while still allowing acetylation and excretion of intracellular polyamines. This leads to a decrease in the naturally occurring polyamines, and as polyamine analogues do not function in cell metabolism, unlike the naturally occurring polyamines, cell division stops and cells die 158, 161, 164.

A study of polyamine metabolism in pre-emergent spores of Enc. cuniculi revealed that microsporidia are reliant on uptake and interconversion of polyamines, rather than synthesis, for maintaining polyamine levels, which makes it possible to use polyamine analogues as a drug for the treatment of microsporidia 165. Several polyamine analogues have demonstrated activity against microsporidia in vitro and in a murine microsporidiosis model. Bis-ethylated 3–3-3 (bis-ethylnorspermine) or 3–4-3 (bis-ethylhomospermine) derivatives were effective in inhibiting microsporidia growth, but also had host cell toxicity 166. Another class of polyamine analogues evaluated for the activity against microsporidia was 3–7-3 derivatives. Bis-phenylbenzyl-substituted 3–7-3 (i.e. 1.15-bis N-[o-(phenyl)benzylamino −4,12-diazapentadecane [BW-1]) was found to inhibit Enc. cuniculi PAO activity 160. Second generation alkyl-substituted polyamine analogues containing a 3–7-3 polyamine back bone were synthesized and several of these compounds had activity against microsporidia both in vitro, without producing overt cytotoxicity in their host cells, and in vivo in a murine infection model 167. The novel synthetic polyamines SL-11158 and SL-11144 were also active against Enc. cuniculi both in vitro and in vivo 168. In addition, another three polyamine analogues were tested in an Ent. bieneusi infection and were compared with the activity of fumagillin. Two of the analogues PG-11302 and PG-11157 had efficacy against Ent. bieneusi infection and were more potent drugs against Ent. bieneusi infection than fumagillin 169.

Due to the reliance of microsporidia being on uptake rather than synthesis of polyamines and the demonstrated anti-microsporidian activity of several polyamines analogues (e.g. BW-1, PG-11302, PG-11157, SL-11144, and SL-11158 [146, 152–155]), searching for new polyamine analogues could be an important future direction for the development of new therapeutic agents for this infection.

4.5. Other therapeutic targets

4.5.1. Chitin synthase

Chitin is part of the microsporidia spore wall. It is important for maintaining the spore cell structure and plays a crucial role in infection and extracellular survival 8, 9, 170. Chitin is synthesized by plasma membrane-associated chitin synthases (CS), which belong to the family of glycosyltransferases, specifically the hexosyltransferases 171, 172. Chitin synthases utilize UDP-N-acetylglucosamine as a substrate to synthesize linear chitin molecules (polymers of β−1,4-N-acetylglucosamine). All characterized fungi, including microsporidia, have chitin synthases and most have multiple genes encoding chitin synthases, with different type of chitin synthases being thought to be used in different stages of the fungal life cycles or for particular cell types 172–175. Due to the importance of chitin to the structure of microsporidia spore wall (Figure 1C) and its absence from mammalian cells, chitin synthase has been considered a prime target for the development of therapeutic agents for microsporidiosis. The best-known chitin synthesis inhibitors are nikkomycins and polyoxins which are the analogs of chitin synthesis substrate, UDP-N-acetylglucosamine172, 176. They act as competitive inhibitors for chitin synthesis, leading to inhibition of septation, chaining, and osmotic swelling of the fungal cell 177. Nikkomycin was shown to inhibit replication of Enc. cuniculi and Enc. hellem in vitro and could induce cell damage in both mature and immature spores (Figure 1C) 178, 179. Polyoxin exhibits an even higher inhibition than Nikkomycin in controlling Enc. hellem in vitro 178. Lufenuron, another chitin synthesis inhibitor was proved to be effective in inhibiting Enc. intestinalis and V. corneae growth in vitro without any detectable toxicity to host cells 180.

4.5.2. Topoisomerase IV

While microsporidia are eukaryotic organisms related to fungi 1–3, 181, a partial gene encoding for the topoisomerase IV subunit (part C), previously only identified in prokaryotes, was seen in the V. corneae genome 182. This suggested that, for some microsporidia, topoisomerase IV could be a potential target for therapy. Fluoroquinolones are antimicrobial compounds which target topoisomerase IV, thereby causing decatenation of intertwined daughter chromosomes to allow for segregation of daughter cells and relaxing negative DNA supercoils 183, 184. Fifteen fluoroquinolones were tested both in vivo and in vitro of microsporidia infection. Lomefloxacin, gatifloxacin, nalidixic acid, and moxifloxacin inhibited both V. corneae and Enc. intestinalis in vitro and had minimal host cell toxicity. Ofloxacin and norfloxacin inhibited Enc. intestinalis replication by more than 70% compared to the control group. Using an in vivo athymic mouse infection model, it was found that ofloxacin, lomefloxacin, gatifloxacin, and norfloxacin increased time of survival of athymic mice infected by V. corneae; however, nalidixic acid and moxifloxacin failed to prolong survival 182. These data illustrate that these drugs could be useful therapeutic agents, although more study is needed to define their therapeutic efficacy for microsporidiosis.

4.5.3. Calcium depended spore germination

Microsporidia process a unique invasion organelle termed polar tube, which coils under the spore wall in microsporidia. One of the mechanisms of microsporidia infection is by the germination of microsporidia spores and transferring the nucleic contained sporoplasm into host cell by the extruded polar tube. The process of spore germination has been reported to be calcium dependent 185. It has been hypothesized that displacement of calcium from the polaroplast membrane would either activate a contractile mechanism or combine with the polaroplast matrix causing polaroplast swelling 186, 187. The calcium antagonists (verapamil and lanthanum) and the calmodulin inhibitors (trifluroperazine and chlorpromazine) were demonstrated to prevent spore germination in Spraguea lophii 185. Nifedipine, which is a calcium channel blocker, has been reported to inhibit the germination of Enc. hellem and Enc. intestinalis spores in vitro 188, 189. However, no in vivo data exists regarding the use of calcium channel blockers in microsporidiosis 190.

5. Conclusion

Microsporidia have become important emerging human infections, particular with the increased use of immunomodulatory agents for disease therapy. These pathogens cause infection in both immune competent and immune compromised individuals. Clinically, microsporidiosis can cause a range of symptoms including chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, renal failure, and fatigue, which carry a significant mortality risk to patients. Albendazole and fumagillin are the most widely used drugs for the therapy of microsporidiosis which use β-tubulin and MetAP2 as targets, respectively. Albendazole is effective for Encephalitozoon spp., however, it is not effective against Ent. bieneusi. Fumagillin has a much broader range of effectiveness against microsporidia, including both Encephalitozoon spp. and Ent. bieneusi. New therapeutic targets for microsporidia include triosephosphate isomerase, chitin synthase, polyamines, and topoisomerase IV. Drugs based on these targets are promising, but there is a need for additional studies before any are ready for clinical trials.

6. Expert opinion

Microsporidia are notoriously reduced and derived intracellular parasites. They have very reduced small genomes and relic mitochondria. Microsporidia lack the tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative metabolism and many lack alternative oxidase. They, therefore, rely more on other energy metabolic pathways such as glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway, and trehalose metabolism. This reduction in energy metabolism pathways makes triosephosphate isomerase an intriguing target for drug design due to its important role in glycolysis in microsporidia. Similarly, the structural and catalytic mechanism differences between other key enzymes involved in microsporidian and human glycolysis pathways as well as other energy metabolic pathways could be compared, and those differences should offer opportunities for the design and synthesis of new anti-microsporidia drugs.

Two polyamine analogues PG-11302 and PG-11157 have been proven to be effective agents for the treatment of microsporidiosis in vitro and in murine infection models. There has been limited development of polyamine analogues and this pathway for the treatment of microsporidiosis and this area deserves further study.

Albendazole is one of the widely used drugs for microsporidiosis therapeutics, but it is less effective for Ent. bieneusi compared with the Encephaliozoonidae, which limits its effectiveness in clinical practice. Ent. bieneusi is the most common microsporidia in human infection and the first microsporidia being reported as the causing of diarrhea in patients with AIDS, so drugs that developed for Ent. bieneusi therapy is even more important. Studies of new benzimidazole analogs that work for organisms resistant to traditional benzimidazoles may yield new therapeutic agents for microsporidia.

Microsporidia lack methionine aminopeptidase type 1 (MetAP1) and are, therefore, dependent on MetAP2, while mammalian cells have both enzymes. Meanwhile, MetAP2 plays a key role in angiogenesis which is required for tumor metastasis in cancer patients. Thus, MetAP2 is an essential enzyme in the Microsporidia and new inhibitors of this pathway have significant promise as therapeutic agents for microsporidiosis. The natural product fumagillin is a selective and potent irreversible inhibitor of MetAP2, and fumagillin and its analogs, TNP-470 have shown promise in vitro and in murine models for the therapy of microsporidiosis, and have been used in clinical studies for the treatment of cancer 191. Fumagillin has a broader anti-microsporidian activity than albendazole and is active against both Ent. bieneusi and Encephaliozoonidae; however, it is not commercially available for human infection in most countries. New compounds that bind MetAP2 have been developed by the pharmaceutical industry as potential anticancer therapies. For example, beloranib (CKD-732) which is a fumagillin derivative, has a much higher anti-angiogenic activity than fumagillin and has been used in a clinical trial 192, and PPI-2458, another fumagillin derivative, has shown efficacy in rodent cancer models and has significant MetAP2 inhibitory activity 193, 194. Fumagillin analogues have been demonstrated to inhibit Enc. cuniculi in vitro and in vivo 15. New MetAP2 inhibitors hold significant promise for the treatment of microsporidiosis.

A limitation of research is that Enterocytozoon bieneusi has not been cultivated continuously in vitro and are no reliable rodent models of this infection. Understanding what is needed to cultivate this pathogen and the development of a robust small animal would clearly facilitate the development of new therapies for this pathogenic microsporidian.

Article Highlights.

Microsporidia are opportunistic pathogens that are widely distributed in nature. They are related to the Cryptomycota and are probably a sister group to the Fungi. They have a broad host range including both invertebrates and vertebrates.

Microsporidiosis in immune deficient patients can be extremely debilitating and carries a significant mortality risk.

Multiple strategies have been used for the diagnosis of microsporidia including light microscopy, transmission electron microscopy, and nucleic acid-based molecular techniques.

Triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) is a new target identified recently for anti-microsporidia drug design. Modification of TIM cysteine (Cys) residues by three different sulfhydryl reagents could inactivate microsporidian TIM, but had little or no effect on human TIM, suggesting that this pathway could be useful for the design of new therapeutic agents

Microsporidia lack methionine aminopeptidase type 1 (MetAP1) and are, therefore, dependent on MetAP2, while mammalian cells have both enzymes. Thus, MetAP2 is an essential enzyme in the Microsporidia and new inhibitors of this pathway have significant promise as therapeutic agents.

Chitin is important for maintaining the structure of microsporidia spore wall, and it is absence in mammalian cells. To this end, like in classical Fungi, chitin synthase is an interesting target for the development of therapeutic agents for microsporidiosis. Chitin synthase inhibitors such as nikkomycins, polyoxins, and lufenuron, have been demonstrated in vitro to inhibit spore replication and alter spore morphology.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This paper was funded by grants AI124753 and AI132614 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health - National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH-NIAID).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers

- 1.Cavalier-Smith T A revised six-kingdom system of life. Biological Reviews 1998;73(3):203–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keeling PJ, Fast NM. Microsporidia: biology and evolution of highly reduced intracellular parasites. Annual Reviews in Microbiology 2002;56(1):93–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vossbrinck CR, Andreadis TG, Weiss LM. Phylogenetics: taxonomy and the microsporidia as derived fungi Opportunistic Infections: Toxoplasma, Sarcocystis, and Microsporidia: Springer; 2004:189–213. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sprague V Systematics of the Microsporidia: Springer, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higes M, Martín R, Meana A. Nosema ceranae, a new microsporidian parasite in honeybees in Europe. Journal of invertebrate pathology 2006;92(2):93–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desportes I, Charpentier YL, Galian A, et al. Occurrence of a new microsporidan: Enterocytozoon bieneusi ng, n. sp., in the enterocytes of a human patient with AIDS. The Journal of protozoology 1985;32(2):250–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weidner E The microsporidian spore invasion tube. The ultrastructure, isolation, and characterization of the protein comprising the tube. J Cell Biol 1976. October;71(1):23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhat SA, Bashir I, Kamili AS. Microsporidiosis of silkworm, Bombyx mori L. (Lepidoptera-bombycidae): A review. African Journal of Agricultural Research 2009. December;4(13):1519–23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chioralia G, Trammer T, Maier WA, et al. Morphologic changes in Nosema algerae (Microspora) during extrusion. Parasitology Research 1998. February;84(2):123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erickson BW, Blanquet RS. The occurrence of chitin in the spore wall of Glugea weissenbergi. Journal of invertebrate pathology 1969;14(3):358–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu Y, Takvorian P, Cali A, et al. Lectin binding of the major polar tube protein (PTP1) and its role in invasion. J Eukaryot Microbiol 2003;50 Suppl:600–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu Y, Takvorian PM, Cali A, et al. Glycosylation of the major polar tube protein of Encephalitozoon hellem, a microsporidian parasite that infects humans. Infect Immun 2004. November;72(11):6341–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frixione E, Ruiz L, Santillán M, et al. Dynamics of polar filament discharge and sporoplasm expulsion by microsporidian spores. Cell motility and the cytoskeleton 1992;22(1):38–50. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han B, Polonais V, Sugi T, et al. The role of microsporidian polar tube protein 4 (PTP4) in host cell infection. PLoS pathogens 2017;13(4):e1006341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiss LM, Becnel JJ. Microsporidia: pathogens of opportunity: John Wiley & Sons, 2014.**This textbook provides a comprehensive summary of what is known about microsporidia and microsporidiosis

- 16.Han B, Weiss LM. Microsporidia: Obligate intracellular pathogens within the fungal kingdom. Microbiology Spectrum 2017;5(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghoshal U, Khanduja S, Pant P, et al. Intestinal microsporidiosis in renal transplant recipients: Prevalence, predictors of occurrence and genetic characterization. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gumbo T, Hobbs RE, Carlyn C, et al. Microsporidia infection in transplant patients. Transplantation 1999;67(3):482–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Didier ES, Weiss LM. Microsporidiosis: not just in AIDS patients. Current opinion in infectious diseases 2011;24(5):490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Texier C, Vidau C, Viguès B, et al. Microsporidia: a model for minimal parasite–host interactions. Current opinion in microbiology 2010;13(4):443–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber R, Bryan RT, Schwartz DA, et al. Human Microsporidial Infections. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 1994. October;7(4):426-&. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Gool T, Luderhoff E, Nathoo K, et al. High prevalence of Enterocytozoon bieneusi infections among HIV-positive individuals with persistent diarrhoea in Harare, Zimbabwe. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1995;89(5):478–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coyle CM, Wittner M, Kotler DP, et al. Prevalence of microsporidiosis due to Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon (Septata) intestinalis among patients with AIDS-related diarrhea: determination by polymerase chain reaction to the microsporidian small-subunit rRNA gene. Clinical infectious diseases 1996;23(5):1002–06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anane S, Attouchi H. Microsporidiosis: epidemiology, clinical data and therapy. Gastroenterologie clinique et biologique 2010;34(8–9):450–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Field AS, Milner DA. Intestinal microsporidiosis. Clinics in laboratory medicine 2015;35(2):445–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sapir A, Dillman AR, Connon SA, et al. Microsporidia-nematode associations in methane seeps reveal basal fungal parasitism in the deep sea. Frontiers in microbiology 2014;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Visvesvara GS. In vitro cultivation of microsporidia of clinical importance. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2002;15(3):401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orenstein JM, Dieterich DT, Kotler DP. Systemic dissemination by a newly recognized intestinal microsporidia species in AIDS. AIDS (London, England) 1992;6(10):1143–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cali A, Kotler DP, Orenstein JM. Septata intestinalis NG, N. Sp., an intestinal microsporidian associated with chronic diarrhea and dissemination in AIDS patients. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 1993;40(1):101–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shadduck JA. Nosema cuniculi: in vitro isolation. Science 1969;166(3904):516–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Didier PJ, Didier ES, Orenstein JM, et al. Fine structure of a new human microsporidian, Encephalitozoon hellem, in culture. The Journal of protozoology 1991;38(5):502–07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Visvesvara GS, Leitch GJ, da Silva AJ, et al. Polyclonal and monoclonal antibody and PCR-amplified small-subunit rRNA identification of a microsporidian, Encephalitozoon hellem, isolated from an AIDS patient with disseminated infection. Journal of clinical microbiology 1994;32(11):2760–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weber R, Kuster H, Visvesvara GS, et al. Disseminated microsporidiosis due to Encephalitozoon hellem: pulmonary colonization, microhematuria, and mild conjunctivitis in a patient with AIDS. Clinical Infectious Diseases 1993;17(3):415–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma S, Das S, Joseph J, et al. Microsporidial keratitis: need for increased awareness. Survey of ophthalmology 2011;56(1):1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis RM, Font RL, Keisler MS, et al. Corneal microsporidiosis: a case report including ultrastructural observations. Ophthalmology 1990;97(7):953–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cali A, Neafie R, Weiss LM, et al. Human vocal cord infection with the microsporidium Anncaliia algerae. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 2010;57(6):562–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Field A, Paik J, Stark D, et al. Myositis due to the microsporidian Anncaliia (Brachiola) algerae in a lung transplant recipient. Transplant Infectious Disease 2012;14(2):169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vávra J, Kamler M, Modrý D, et al. Opportunistic nature of the mammalian microsporidia: experimental transmission of Trachipleistophora extenrec (Fungi: Microsporidia) between mammalian and insect hosts. Parasitology research 2011;108(6):1565–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weber R, Deplazes P, Schwartz D. Diagnosis and clinical aspects of human microsporidiosis. Contributions to Microbiology 2000;6:166–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Franzen C, Muller A. Microsporidiosis: human diseases and diagnosis. Microbes and Infection 2001. April;3(5):389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Costa SF, Weiss LM. Drug treatment of microsporidiosis. Drug Resistance Updates 2000;3(6):384–99.*This paper provides an overview of therapeutic agents for the treatment of microsporiosis in aniamls and humans.

- 42.Cama VA, Pearson J, Cabrera L, et al. Transmission of Enterocytozoon bieneusi between a child and guinea pigs. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2007;45(8):2708–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li W, Cama V, Feng Y, et al. Population genetic analysis of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in humans. International journal for parasitology 2012;42(3):287–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Champion L, Durrbach A, Lang P, et al. Fumagillin for treatment of intestinal microsporidiosis in renal transplant recipients. American Journal of Transplantation 2010;10(8):1925–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Terada S, Reddy KR, Jeffers LJ, et al. Microsporidan hepatitis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Annals of internal Medicine 1987;107(1):61–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sheth S, Bates C, Federman M, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure caused by microsporidial infection in a patient with AIDS. AIDS (London, England) 1997;11(4):553–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsubayashi H, Koike T, Mikata I, et al. A case of Encephalitozoon-like body infection in man. Arch Pathol 1959;67(2):181–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vavra J, Yachnis AT, Shadduck JA, et al. Microsporidia of the genus Trachipleistophora--causative agents of human microsporidiosis: description of Trachipleistophora anthropophthera n. sp. (Protozoa: Microsporidia). J Eukaryot Microbiol 1998. May-Jun;45(3):273–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yachnis AT, Berg J, Martinez-Salazar A, et al. Disseminated microsporidiosis especially infecting the brain, heart, and kidneys: report of a newly recognized pansporoblastic species in two symptomatic AIDS patients. American journal of clinical pathology 1996;106(4):535–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lowder CY, McMahon JT, Meisler DM, et al. Microsporidial keratoconjunctivitis caused by Septata intestinalis in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. American journal of ophthalmology 1996;121(6):715–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rastrelli P, Didier E, Yee R . Microsporidial keratitis. Ophthalmol Clin North Am 1994;7:614–35. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mertens RB, Didier ES, Fishbein MC, et al. Encephalitozoon cuniculi microsporidiosis: infection of the brain, heart, kidneys, trachea, adrenal glands, and urinary bladder in a patient with AIDS. Modern pathology: an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc 1997;10(1):68–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meissner EG, Bennett JE, Qvarnstrom Y, et al. Disseminated microsporidiosis in an immunosuppressed patient. Emerging infectious diseases 2012;18(7):1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Choudhary MM, Metcalfe MG, Arrambide K, et al. Tubulinosema sp. microsporidian myositis in immunosuppressed patient. Emerging infectious diseases 2011;17(9):1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cali A, Takvorian PM. Ultrastructure and Development of Pleistophora ronneafiei n. sp., a Microsporidium (Protista) in the Skeletal Muscle of an Immune‐Compromised Individual. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 2003;50(2):77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chupp GL, Alroy J, Adelman LS, et al. Myositis due to Pleistophora (Microsporidia) in a patient with AIDS. Clinical infectious diseases 1993;16(1):15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Franzen C, Nassonova ES, Schölmerich J, et al. Transfer of the members of the genus Brachiola (microsporidia) to the genus Anncaliia based on ultrastructural and molecular data. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 2006;53(1):26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cali A, Takvorian PM, Lewin S, et al. Brachiola vesicularum, n. g., n. sp., a new microsporidium associated with AIDS and myositis. J Eukaryot Microbiol 1998. May-Jun;45(3):240–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Molina J-M, Oksenhendler E, Beauvais B, et al. Disseminated microsporidiosis due to Septata intestinalis in patients with AIDS: clinical features and response to albendazole therapy. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1995;171(1):245–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gunnarsson G, Hurlbut D, DeGirolami PC, et al. Multiorgan microsporidiosis: report of five cases and review. Clinical infectious diseases 1995;21(1):37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weber R, Bryan RT. Microsporidial infections in immunodeficient and immunocompetent patients. Clinical Infectious Diseases 1994;19(3):517–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Galván A, Sánchez AM, Valentín MP, et al. First cases of microsporidiosis in transplant recipients in Spain and review of the literature. Journal of clinical microbiology 2011;49(4):1301–06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.George B, Coates T, Mcdonald S, et al. Disseminated microsporidiosis with Encephalitozoon species in a renal transplant recipient. Nephrology 2012;17(s1):5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leitchd DAS, Chevez-Barrios P, Sara W, et al. Isolation of Nosema algerae from the cornea of an immunocompetent patient. Microsporidia at the Turn of the Millenium: Raleigh 1999 1999;46(5):10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kester KE, Visvesara GS, McEvoy P. Organism responsible for nodular cutaneous microsporidiosis in a patient with AIDS. Annals of internal medicine 2000;133(11):925–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schwartz DA, Bryan RT, Hewan-Lowe KO, et al. Disseminated microsporidiosis (Encephalitozoon hellem) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Autopsy evidence for respiratory acquisition. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 1992;116(6):660–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weiss LM. Microsporidia: emerging pathogenic protists. Acta tropica 2001;78(2):89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stentiford G, Becnel J, Weiss L, et al. Microsporidia–emergent pathogens in the global food chain. Trends in parasitology 2016;32(4):336–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van Gool T, Snijders F, Reiss P, et al. Diagnosis of intestinal and disseminated microsporidial infections in patients with HIV by a new rapid fluorescence technique. Journal of Clinical Pathology 1993;46(8):694–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vavra J, Dahbiova R, Hollister W, et al. Staining of microsporidian spores by optical brighteners with remarks on the use of brighteners for the diagnosis of AIDS associated human microsporidioses. Folia parasitologica 1992;40(4):267–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weber R, Bryan RT, Owen RL, et al. Improved light-microscopical detection of microsporidia spores in stool and duodenal aspirates. New England Journal of Medicine 1992;326(3):161–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Procop GW. Molecular diagnostics for the detection and characterization of microbial pathogens. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2007;45(Supplement_2):S99–S111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zainudin NS, Nasarudin SNSa, Moktar N, et al. Human microsporidiosis in Malaysia: Review of literatures. Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine 2017;17(2):9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Garcia LS. Laboratory Identification of the Microsporidia. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2002;40(6):1892–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Al-Mekhlafi MA, Fatmah M, Anisah N, et al. Species identification of intestinal microsporidia using immunofluorescence antibody assays. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health 2011;42(1):19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Field AS. Light microscopic and electron microscopic diagnosis of gastrointestinal opportunistic infections in HIV-positive patients. Pathology 2002;34(1):21–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Field A, Marriott D, Hing M. The Warthin-Starry stain in the diagnosis of small intestinal microsporidiosis in HIV-infected patients. Folia Parasitol (Praha) 1993;40(4):261–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Talabani H, Sarfati C, Pillebout E, et al. Disseminated infection with a new genovar of Encephalitozoon cuniculi in a renal transplant recipient. Journal of clinical microbiology 2010;48(7):2651–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thellier M, Breton J. Enterocytozoon bieneusi in human and animals, focus on laboratory identification and molecular epidemiology. EDP Sciences 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ghosh K, Weiss LM. Molecular diagnostic tests for microsporidia. Interdisciplinary perspectives on infectious diseases 2009;2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fedorko DP, Nelson NA, Cartwright CP. Identification of microsporidia in stool specimens by using PCR and restriction endonucleases. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 1995;33(7):1739–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Katzwinkel‐Wladarsch S, Lieb M, Heise W, et al. Direct amplification and species determination of microsporidian DNA from stool specimens. Tropical Medicine & International Health 1996;1(3):373–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhao W, Wang J, Yang Z, et al. Dominance of the Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotype BEB6 in red deer (Cervus elaphus) and Siberian roe deer (Capreolus pygargus) in China and a brief literature review. Parasite 2017;24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vossbrinck CR, Maddox JV, Friedman S, et al. Ribosomal RNA sequence suggests microsporidia are extremely ancient eukaryotes. Nature 1987;326(6111):411–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.El-Kerdany E, Ahmed S, Gaafar M, et al. Simultaneous diagnosis and species identification of microsporidial infection in human stool samples using real-time polymerase chain reaction. J Adv Parasitol 2016;3(4):104–16. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Polley SD, Boadi S, Watson J, et al. Detection and species identification of microsporidial infections using SYBR Green real-time PCR. Journal of medical microbiology 2011;60(4):459–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wolk D, Schneider S, Wengenack N, et al. Real-time PCR method for detection of Encephalitozoon intestinalis from stool specimens. Journal of clinical microbiology 2002;40(11):3922–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Carville A, Mansfield K, Widmer G, et al. Development and application of genetic probes for detection of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in formalin-fixed stools and in intestinal biopsy specimens from infected patients. Clinical and diagnostic laboratory immunology 1997;4(4):405–08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Velasquez JN, Carnevale S, Labbe JH, et al. In situ hybridization: a molecular approach for the diagnosis of the microsporidian parasite Enterocytozoon bieneusi. Human pathology 1999;30(1):54–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hester JD, Alan Lindquist H, Bobst AM, et al. Fluorescent in situ detection of Encephalitozoon hellem spores with a 6‐carboxyfluorescein‐labeled ribosomal RNA‐targeted oligonucleotide probe. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 2000;47(3):299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hollister W, Canning E, Willcox A. Evidence for widespread occurrence of antibodies to Encephalitozoon cuniculi (Microspora) in man provided by ELISA and other serological tests. Parasitology 1991;102(1):33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Didier E, Shadduck J, Didier P, et al. Studies on ocular microsporidia. The Journal of protozoology 1991;38(6):635–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Beckwith C, Peterson N, Liu J, et al. Dot enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (dot ELISA) for antibodies to Encephalitozoon cuniculi. Laboratory animal science 1988;38(5):573–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Singh M, Kane G, Mackinlay L. Detection of antibodies to Nosema cuniculi (Protozoa: Microsporida) in human and animal sera by the indirect fluorescent antibody technique. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health 1982;13(1):110–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Weiss LM, Cali A, Levee E, et al. Diagnosis of Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection by western blot and the use of cross-reactive antigens for the possible detection of microsporidiosis in humans. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 1992;47(4):456–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Franzen C, Müller A. Molecular techniques for detection, species differentiation, and phylogenetic analysis of microsporidia. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 1999;12(2):243–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fedorko DP, Hijazi YM. Application of molecular techniques to the diagnosis of microsporidial infection. Emerging infectious diseases 1996;2(3):183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Boot R, Hansen AK, Hansen C, et al. Comparison of assays for antibodies to Encephalitozoon cuniculi in rabbits. Laboratory animals 2000;34(3):281–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Khan IA, Moretto M, Weiss LM. Immune response to Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection. Microbes and infection 2001;3(5):401–05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.La’Toya VL, Bradley CW, Wyre NR. Encephalitozoon cuniculi in pet rabbits: diagnosis and optimal management. Veterinary Medicine: Research and Reports 2014;5:169–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Abu-Akkada SS, Ashmawy KI, Dweir AW. First detection of an ignored parasite, Encephalitozoon cuniculi, in different animal hosts in Egypt. Parasitology research 2015;114(3):843–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jordan CN, Zajac AM, Lindsay DS. Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection in rabbits. Parasitology 2006;28(2). [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pakes SP, Gerrity LW. Protozoal diseases. The Biology of the Laboratory Rabbit (Second Edition): Elsevier; 1994:205–29. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Corradi N, Pombert JF, Farinelli L, et al. The complete sequence of the smallest known nuclear genome from the microsporidian Encephalitozoon intestinalis. Nature Communications 2010;1(1):67–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Williams BAP, Hirt RP, Lucocq JM, et al. A mitochondrial remnant in the microsporidian Trachipleistophora hominis. Nature 2002. 08/22/online;418:865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Van Der Giezen M, Tovar J. Degenerate mitochondria. EMBO reports 2005;6(6):525–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Williams BA, Keeling PJ. Cryptic organelles in parasitic protists and fungi. Adv Parasitol 2003;54:9–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Keeling PJ, Corradi N. Shrink it or lose it: balancing loss of function with shrinking genomes in the microsporidia. Virulence 2011;2(1):67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.García-Torres I, Hernández-Alcántara G, Molina-Ortiz D, et al. First characterization of a microsporidial triosephosphate isomerase and the biochemical mechanisms of its inactivation to propose a new druggable target. Scientific reports 2018;8(1):8591.**This study demonstrated the mechanisms of inactivation of this enzyme by thiol-reactive compounds and demonstrated that omeprazole, rabeprazole and sulbutiamine can effectively inactivate this microsporidial enzyme. This suggested that these agents were promising lead compounds for the development of new therapeutic agents for microsporidiosis.

- 110.Aguilera E, Varela J, Birriel E, et al. Potent and selective inhibitors of Trypanosoma cruzi triosephosphate isomerase with concomitant inhibition of cruzipain: inhibition of parasite growth through multitarget activity. ChemMedChem 2016;11(12):1328–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ogungbe IV, Setzer WN. Comparative molecular docking of antitrypanosomal natural products into multiple Trypanosoma brucei drug targets. Molecules 2009;14(4):1513–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rodríguez-Romero A, Hernandez-Santoyo A, del Pozo Yauner L, et al. Structure and inactivation of triosephosphate isomerase from Entamoeba histolytica. Journal of molecular biology 2002;322(4):669–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.García-Torres I, Marcial-Quino J, Gómez-Manzo S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors drastically modify triosephosphate isomerase from Giardia lamblia at functional and structural levels, providing molecular leads in the design of new antigiardiasic drugs. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects 2016;1860(1):97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Enriquez-Flores S, Rodriguez-Romero A, Hernandez-Alcantara G, et al. Species-specific inhibition of Giardia lamblia triosephosphate isomerase by localized perturbation of the homodimer. Molecular and biochemical parasitology 2008;157(2):179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Katiyar S, Gordon V, McLaughlin G, et al. Antiprotozoal activities of benzimidazoles and correlations with beta-tubulin sequence. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 1994;38(9):2086–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Davidse LC. Benzimidazole fungicides: mechanism of action and biological impact. Annual review of phytopathology 1986;24(1):43–65. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lacey E Mode of action of benzimidazoles. Parasitology Today 1990;6(4):112–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zhou Y, Xu J, Zhu Y, et al. Mechanism of action of the benzimidazole fungicide on Fusarium graminearum: interfering with polymerization of monomeric tubulin but not polymerized microtubule. Phytopathology 2016;106(8):807–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tuncbilek M, Kiper T, Altanlar N. Synthesis and in vitro antimicrobial activity of some novel substituted benzimidazole derivatives having potent activity against MRSA. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2009;44(3):1024–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Edlind T, Katiyar S, Visvesvara G, et al. Evolutionary origins of microsporidia and basis for benzimidazole sensitivity: an update. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 1996;43(5):109S–09S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Weiss L, Michalakakis E, Coyle C, et al. The in vitro activity of albendazole against Encephalitozoon cuniculi. The Journal of eukaryotic microbiology 1994;41(5). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Colbourn NI, Hollister WS, Curry A, et al. Activity of albendazole against Encephalitozoon cuniculi in vitro. European journal of protistology 1994;30(2):211–20. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Fayer R, Fetterer R. Activity of benzimidazoles against cryptosporidiosis in neonatal BALB/c mice. The Journal of parasitology 1995;81(5):794–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Katiyar S, Edlind T. In vitro susceptibilities of the AIDS-associated microsporidian Encephalitozoon intestinalis to albendazole, its sulfoxide metabolite, and 12 additional benzimidazole derivatives. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 1997;41(12):2729–32.*This paper provides an overview of the activity of various benzimidazoles against microsporodia.

- 125.Radek R, Wurzbacher C, Gisder S, et al. Morphologic and molecular data help adopting the insect-pathogenic nephridiophagids (Nephridiophagidae) among the early diverging fungal lineages, close to the Chytridiomycota. MycoKeys 2017;25:31. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Radek R, Herth W. Ultrastructural investigation of the spore-forming protist Nephridiophaga blattellae in the Malpighian tubules of the German cockroach Blattella germanica. Parasitology research 1999;85(3):216–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Weiss LM. Clinical syndromes associated with microsporidiosis. Microsporidia: pathogens of opportunity 2014:371–401. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Dore GJ, Marriott DJ, Hing MC, et al. Disseminated microsporidiosis due to Septata intestinalis in nine patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: response to therapy with albendazole. Clinical infectious diseases 1995;21(1):70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Blanshard C, Ellis D, Dowell S, et al. Electron microscopic changes in Enterocytozoon bieneusi following treatment with albendazole. Journal of clinical pathology 1993;46(10):898–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.De Groote MA, Visvesvara G, Wilson ML, et al. Polymerase chain reaction and culture confirmation of disseminated Encephalitozoon cuniculi in a patient with AIDS: successful therapy with albendazole. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1995;171(5):1375–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Santiana M, Pau C, Takvorian PM, et al. Analysis of the Beta‐Tubulin Gene and Morphological Changes of the Microsporidium Anncaliia algerae both Suggest Albendazole Sensitivity. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 2015;62(1):60–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Dieterich DT, Lew EA, Kotler DP, et al. Treatment with albendazole for intestinal disease due to Enterocytozoon bieneusi in patients with AIDS. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1994;169(1):178–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Soule JB, Halverson AL, Becker RB, et al. A patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and untreated Encephalitozoon (Septata) intestinalis microsporidiosis leading to small bowel perforation. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine 1997;121(8):880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Arfin SM, Kendall RL, Hall L, et al. Eukaryotic methionyl aminopeptidases: two classes of cobalt-dependent enzymes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1995;92(17):7714–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zuo S, Guo Q, Ling C, et al. Evidence that two zinc fingers in the methionine aminopeptidase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae are important for normal growth. Molecular and General Genetics MGG 1995;246(2):247–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Lowther WT, Matthews BW. Structure and function of the methionine aminopeptidases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology 2000;1477(1–2):157–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Atanassova A, Sugita M, Sugiura M, et al. Molecular cloning, expression and characterization of three distinctive genes encoding methionine aminopeptidases in cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. Archives of microbiology 2003;180(3):185–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Larrabee JA, Leung CH, Moore RL, et al. Magnetic Circular Dichroism and Cobalt (II) Binding Equilibrium Studies of Escherichia c oli Methionyl Aminopeptidase. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2004;126(39):12316–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Bennett B, Holz RC. EPR studies on the mono-and dicobalt (II)-substituted forms of the aminopeptidase from Aeromonas proteolytica. Insight into the catalytic mechanism of dinuclear hydrolases. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1997;119(8):1923–33. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Johansson FB, Bond AD, Nielsen UG, et al. Dicobalt II− II, II− III, and III− III Complexes as Spectroscopic Models for Dicobalt Enzyme Active Sites. Inorganic chemistry 2008;47(12):5079–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Folkman J Angiogenesis in cancer, vascular, rheumatoid and other disease. Nature medicine 1995;1(1):27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Bontems F, le Floch P, Duffieux F, et al. Homology modeling and calculation of the cobalt cluster charges of the Encephazlitozoon cuniculi methionine aminopeptidase, a potential target for drug design. Biophysical chemistry 2003;105(1):29–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Weiss LM, ZHOU GC, Zhang H. Characterization of recombinant microsporidian methionine aminopeptidase type 2. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 2003;50:597–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Zhang H, Huang H, Cali A, et al. Investigations into microsporidian methionine aminopeptidase type 2: a therapeutic target for microsporidiosis. Folia parasitologica 2005;52(1–2):182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Katinka MD, Duprat S, Cornillot E, et al. Genome sequence and gene compaction of the eukaryote parasite Encephalitozoon cuniculi. Nature 2001;414(6862):450–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Sin N, Meng L, Wang MQ, et al. The anti-angiogenic agent fumagillin covalently binds and inhibits the methionine aminopeptidase, MetAP-2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1997;94(12):6099–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Lowther WT, McMillen DA, Orville AM, et al. The anti-angiogenic agent fumagillin covalently modifies a conserved active-site histidine in the Escherichia coli methionine aminopeptidase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998;95(21):12153–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Coyle C, Kent M, Tanowitz HB, et al. TNP-470 is an effective antimicrosporidial agent. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1998;177(2):515–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Higgins M, Kent M, Moran J, et al. Efficacy of the fumagillin analog TNP-470 for Nucleospora salmonis and Loma salmonae infections in chinook salmon Oncorhynchus tshawytscha. Diseases of aquatic organisms 1998;34(1):45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Molina J-M, Tourneur M, Sarfati C, et al. Fumagillin treatment of intestinal microsporidiosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2002;346(25):1963–69.*An important study demonstrating fumagillin is active for the treatment of Ent. bieneusi infeciton in pateints with HIV infeciton.