Abstract

Background: The Australian/Canadian Osteoarthritis Hand Index (AUSCAN) and Patient-Rated Wrist-Hand Evaluation (PRWHE) are 2 patient-related outcome measures to assess pain and disability in patients with osteoarthritis (OA). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the AUSCAN and PRWHE in a large-scale, longitudinal cohort of patients with early thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) OA. Methods: We obtained baseline data on 135 individuals (92 with early CMC OA participants and 43 asymptomatic controls) and at follow-up (year 1.5) on 83 individuals. We assessed the internal consistency using Cronbach alpha, and construct and criterion validity using other pain scales and objective measures of strength, respectively. We also examined the correlation between the AUSCAN and PRWHE and correlation coefficients at baseline and follow-up, as well as the correlation between changes in these instruments over the follow-up period. Results: Internal consistency was high for both AUSCAN and PRWHE totals and subscales (Cronbach α > 0.70). Both instruments demonstrated construct validity compared with the Verbal Rating Scale (r = 0.52-0.60, P < .01), an assessment of pain, and moderate criterion validity compared with key pinch and grip strength (r = −.24 to −.33, P < .05). These instruments were highly correlated with each other at baseline and follow-up time points (r = 0.76−.94, P < .01), and changes in a patient’s total scores over time were also correlated (r = 0.83, P < .01). Conclusions: The AUSCAN and PRWHE are both valid assessments for pain and/or disability in patients with early thumb CMC OA.

Keywords: osteoarthritis, thumb, hand, carpometacarpal, AUSCAN, PRWHE

Introduction

Thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) osteoarthritis (OA) is a common disease affecting up to 11% and 33% of men and women, respectively, between the ages 50 and 60 and up to 90% over the age of 80.3,12 The progression of thumb CMC OA results in pain, reduced strength, and functional impairment.9 Variable operative and nonoperative treatments exist to relieve symptoms, restore strength and function, and slow the progression of the disease.19,32

Self-reported outcome measures are important components of the patient assessment during hand therapy, nonsurgical management, and surgical treatment of CMC OA.21 Several patient self-report scales have been developed for the upper extremity, including the Australian/Canadian Osteoarthritis Hand Index (AUSCAN)1,4; the Patient-Rated Wrist-Hand Evaluation (PRWHE)28; the Arthritis Hand Function Test (AHFT)2; the Cochin Hand Function Scale29; the Functional Index for Hand Osteoarthritis (FIHOA); the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH)8,13,22; and the Michigan Hand Questionnaire (MHQ).7,31 A provider’s choice of instrument depends on its reliability for a given population, responsiveness in detecting clinically important changes, and practicality with respect to time, money, and ease of use.

The AUSCAN4 is a 15-item scale measuring pain (5 items), stiffness (1 item), and function (9 items) during the preceding 48 hours. AUSCAN scores, described in detail by Bellamy and colleagues,5 have total scores that range from 0 to 60, pain subscales that range from 0 to 20, stiffness subscales that range from 0 to 4, and function subscales that range from 0 to 36; higher scores indicate a greater level of intensity. The PRWHE is a 15-item scale that addresses pain and disability related to wrist and hand disorders during the preceding 2 weeks, similarly with higher scores indicating worse pain or disability. The score ranges from 0 to 100 points; 50 points are allocated to 5 pain items and 50 points to 10 functional items, with the total score being a simple sum of these subscales. One supplemental question on appearance of the affected hand is scored separately. Previous studies have shown that both the AUSCAN and PRWHE have acceptable internal consistency, construct validity, factorial validity, and responsiveness for patients with moderate to advanced hand and thumb CMC OA.1,4,5,21,22,26

This study utilized the AUSCAN and PRWHE to assess self-reported pain and disability in a cohort of participants with early thumb CMC OA. While previous studies have compared the AUSCAN and PRWHE in end-stage CMC OA following tendon interposition arthroplasty,21,23 no studies exist that have compared these instruments in patients with early thumb CMC OA who are followed on a longitudinal basis as they develop more advanced OA. Self-report instruments that have been validated only in end-stage disease may not be reliable in participants with early OA: The instrument may not be sensitive enough to detect clinically significant differences in early disease.21

The purpose of this study was to examine the internal consistency, construct validity, and criterion validity of the AUSCAN and PRWHE, over time, in a population with early CMC OA.14,15,20,25 We also conducted hypothesis testing to determine whether these instruments were correlated with each other at baseline and follow-up. We hypothesized that (1) the AUSCAN and PRWHE would be internally consistent in measuring pain and function at baseline and follow-up visits; (2) they would demonstrate construct and criterion validity with other pain scales and objective measures of hand strength, respectively; and (3) scores from these instruments would be highly correlated with each other in a cohort with early thumb CMC OA.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

Participants with early CMC OA and asymptomatic controls were recruited prospectively in a larger study investigating the thumb CMC joint.14,15,20,25 Baseline (year 0) tests were conducted on 135 individuals (92 early OA and 43 controls), and follow-up tests (after 1.5 years) were conducted on 83 of the early OA participants with 9 lost to follow-up or progressing to surgery. Analysis of the properties of the instruments was restricted to the early OA cohort, which included the 92 individuals at baseline and 83 at follow-up. Data analysis was conducted 2.5 years after patients were enrolled.

The study was performed at secondary-care referral facilities, Stanford University and Brown University, and prior institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained at both sites. Participants were consented prior to data collection, and radiographs and participant history were used to determine inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants. Age-matched controls were recruited based on convenience and/or unrelated contralateral hand complaints that did not fulfill exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria of early OA participants included both pain or discomfort complaints at the base of the thumb and radiographs rated as modified Eaton score 0 or 1 by senior hand surgeons (A.L.L. and A.-P.C.W.).10,11,18 Exclusion criteria included rheumatoid arthritis, any inflammatory joint disease, connective tissue disease, metabolic bone disease, history of wrist and thumb fractures, ligamentous injury, or prior significant ipsilateral hand surgery.25 AUSCAN and PRWHE surveys were administered during both baseline and follow-up visits. All patients agreed to complete the surveys, any skipped items were omitted from the analysis and the average number of missing items was reported for each subscale (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Early Thumb CMC OA Cohort.

| Baseline mean (SD) | Baseline range | Follow-up mean | Follow-up range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, y | 56.4 (7.61) | 41-75 | ||

| Percentage male | 0.47 | 0-1 | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.9 (5.22) | 17.8-49.4 | ||

| AUSCAN | ||||

| Total (scale 0-60) | 18.4 (11.98) | 2-51 | 17.0 (10.45) | 0-56 |

| Pain subscale (scale 0-20) | 6.6 (4.07) | 0-18 | 6.4 (3.98) | 0-19 |

| Function subscale (scale 0-36) | 10.9 (7.73) | 0-31 | 10.3 (6.53) | 0-33 |

| PRWHE | ||||

| Total (scale 0-100) | 28.7 (21.61) | 1-87.5 | 25.5 (19.66) | 0-94 |

| Pain subscale (scale 0-50) | 17.4 (11.65) | 0-44 | 15.8 (10.64) | 0-48 |

| Function subscale (scale 0-50) | 11.3 (10.83) | 0-44.5 | 9.8 (9.70) | 0-46 |

| VRS (scale 0-50) | 10.0 (8.37) | 1-36 | ||

| Key pinch strength, kg | 7.0 (2.29) | 1.4-13.0 | ||

| Average grip strength, kg | 29.6 (11.6) | 4.9-59.4 | ||

Note. N = 92 at baseline, N = 83 at follow-up. Percentage of missing values, AUSCAN: baseline (0% pain, 1% function) and follow-up (0% pain, 1% function). Percentage of missing values, PRWHE: baseline (1% pain, 15% function) and follow-up (2% pain, 6% function). CMC = carpometacarpal; OA = osteoarthritis; BMI = body mass index; AUSCAN = Australian/Canadian Osteoarthritis Hand Index; PRWHE = Patient-Rated Wrist-Hand Evaluation; VRS = Verbal Rating Scale.

Data Analysis

This study adhered to the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) guidelines for the critical appraisal of health measurement properties and patient-reported outcomes.27 Prior to testing the measurement properties of the self-report measures in the OA cohort, we first compared their AUSCAN and PRWHE scores with the control group to assure that there were detectable differences in patients with early disease versus asymptomatic controls. Means, standard deviations, and ranges were calculated to examine the distributions of the scores of each instrument. Student’s t tests were conducted to compare test scores for controls and symptomatic participants and to determine whether the mean change in scores between baseline and follow-up was statistically significant.

Thereafter, we assessed the internal consistency of the AUSCAN and PRWHE totals as well as individual subscales for the OA cohort at baseline and 1.5-year follow-up. Per COSMIN guidelines, we first used a factor analysis to confirm the unidimensionality of each subscale and the adequacy of sample size. In terms of statistical methods, we then used Cronbach’s alpha to measure internal consistency, which we defined as the degree of interrelatedness between the items within a given scale or subscale.27

To examine construct validity, the degree to which the instrument measures the construct being measured, we compared the pain subscale of each tool with a Verbal Rating Scale (VRS) measurement of pain. The VRS was measured as the sum of the pain during pinching, grasping, twisting, and occupational and avocational tasks measured from 0 to 50, with 0 being the lowest and 50 the highest16; this comparison was used to assess how accurately the AUSCAN and PRWHE measured this concept of “pain.” Criterion validity was assessed using the similar COSMIN guidelines, comparing the function subscales of the AUSCAN and the PRWHE with a “gold standard” objective measurement of strength. We measured key pinch and grip strength on a Greenleaf Sensor (Greenleaf Medical Systems, Palo Alto, California). Key pinch was obtained by holding the sensor between the thumb and the radial aspect of the first digit near the proximal interphalangeal joint. Grip strength was measured with the elbow flexed at 90°, wrist in neutral position, with the thumb parallel to the 4 digits around an instrumented digital dynamometer. The maximum measurements of three independent tests were averaged to calculate the pinch and grip variables.

To further assess construct validity, we conducted hypothesis testing to assess the correlation between the corresponding “pain” and “function” subscales, in addition to the “total” sum of these 2 scales, at both the baseline and follow-up. As there is no corresponding “symptoms” subscale on the PRWHE, nor an “appearance” question on the AUSCAN, these subscales were not included in the analysis as they did not purport to measure the same construct by the COSMIN definitions.

Cronbach alpha and Pearson correlation coefficients were deemed significant with a P < .01. A Cronbach alpha of 0.70 was used as the cutoff for adequate reliability. All statistics were calculated using SPSS Statistics Desktop (IMB Inc, Armonk, New York) or Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Inc, Redmond, Washington).

Results

The OA cohort consisted of 92 baseline and 83 of the baseline patients followed-up after 1.5 years, with a mean age of 56.4 years and standard deviation of 7.6 years at baseline (Table 1). There were near equal numbers of male and female patients (49 female, 43 male). The early OA cohort had significantly higher total AUSCAN and PRWHE scores, as well as higher scores for each of the subscales, than the asymptomatic controls at the baseline visit (P < 0.01).

The AUSCAN and PRWHE demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.88-0.99) for the early OA cohort at the baseline and follow-up visits (Table 2). Analysis of the construct validity of the pain subscale demonstrated moderate (r = 0.52−.58, P < .01) correlation between VRS pain and baseline PRWHE and AUSCAN pain and function (Table 4).

Table 2.

Internal Consistency of AUSCAN/PRWHE at Baseline and Follow-up.

| Baseline | Follow-up | |

|---|---|---|

| AUSCAN | ||

| Total | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| Pain subscale | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| Function subscale | 0.95 | 0.93 |

| PRWHE | ||

| Total | 0.97 | 0.96 |

| Pain subscale | 0.99 | 0.83 |

| Function subscale | 0.97 | 0.96 |

Note. N = 92 at baseline, N = 83 at follow-up. Internal consistency of AUSCAN and PRWHE as measured by Cronbach alpha. Coefficients were deemed to demonstrate “good” consistency when α > 0.70. AUSCAN = Australian/Canadian Osteoarthritis Hand Index; PRWHE = Patient-Rated Wrist-Hand Evaluation.

Table 4.

Construct and Criterion Validity of the AUSCAN/PRWHE at Baseline.

| VRS pain | Average key pinch, kg | Average grip strength, kg | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUSCAN | |||

| Pain subscale | 0.52** | −0.27** | −0.28** |

| Function subscale | 0.60** | −0.31** | −0.31** |

| PRWHE | |||

| Pain subscale | 0.58** | −0.29** | −0.33** |

| Function subscale | 0.58** | −0.24* | −0.24* |

Note. Total was calculated as the sum of the pain and function subscales. N = 92 at baseline, N = 83 at follow-up. Construct validity assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) between scales at baseline (year 0). AUSCAN = Australian/Canadian Osteoarthritis Hand Index; PRWHE = Patient-Rated Wrist-Hand Evaluation.

Significant at P < .05. **Significant at P < .01.

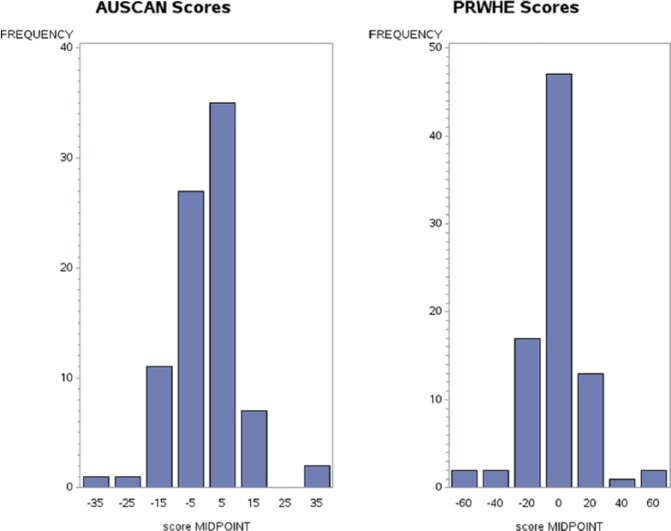

The pain and function subscales showed low correlation with baseline key pinch and grip strength (r = −.24 to 0.33, P < .05) in our assessment of criterion validity. Hypothesis testing demonstrated a high correlation between the AUSCAN and the PRWHE at both baseline (Table 3) and follow-up visits (P < .01; Table 3). The highest association was observed between corresponding subscales of AUSCAN and PRWHE. AUSCAN pain and PRWHE function and AUSCAN function and PRWHE pain subscales were also highly correlated. Changes in the total PRWHE correlated well to changes in the total AUSCAN (r = 0.83, P < .01), which was greater than the correlation between each of the function subscales (r = 0.71, P < .01) and the pain subscales (r = 0.56, P < .01) (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Correlation Between AUSCAN/PRWHE at Baseline and Follow-up.

| Baseline |

Follow-up |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRWHE subscales |

||||||

| Total | Pain | Function | Total | Pain | Function | |

| AUSCAN subscales | ||||||

| Total | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.9 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.84 |

| Pain | 0.9 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.76 |

| Function | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.81 |

Note. Total was calculated as the sum of the pain and function subscales. N = 92 at baseline, N = 83 at follow-up. Construct validity assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) between scales at baseline (year 0). All coefficients were deemed significant at P = .01. AUSCAN = Australian/Canadian Osteoarthritis Hand Index; PRWHE = Patient-Rated Wrist-Hand Evaluation.

Figure 1.

Difference in AUSCAN and PRWHE scores, baseline and 1.5-year follow-up.

Note. Histogram of changes in AUSCAN and PRWHE between baseline and 1.5-year follow-up visits, indicating symmetrically distributed changes. Graph bin width 10 for AUSCAN, 20 for PRWHE. AUSCAN = Australian/Canadian Osteoarthritis Hand Index; PRWHE = Patient-Rated Wrist-Hand Evaluation.

Discussion

This study compared the internal consistency, construct and criterion validity, and the correlation between the AUSCAN and PRWHE in a cohort of patients with early thumb CMC OA. As there is no gold standard to assess pain and function in CMC OA,6 we compared the psychometric properties of 2 well-known instruments of upper extremity disability. Our work provides evidence that these instruments demonstrate similar characteristics in a population of patients with early thumb CMC OA.

Prior studies have compared the 2 measures in a more advanced CMC OA population.23 Importantly, our study evaluated these instruments in early thumb CMC OA and over time as each individual’s OA progressed; validation of these instruments during initial clinical presentation is important to guide valuable treatment decision milestones. The reported total scores of disability for PRWHE and AUSCAN in this early OA population are about half as high as other studies with more advanced OA.23 While these patients were selected based on mild (modified Eaton 0 or I) radiographic changes, the early OA cohort still demonstrated statistically higher AUSCAN and PRWHE scores compared with controls. This supports the notion that these instruments can still distinguish early CMC OA from asymptomatic participants at this stage of the disease. These differences in baseline PRWHE and AUSCAN support the fact that patients were recruited based on a subjective history of basilar thumb pain; however, these instruments had not yet been validated for this population.

Internal consistency was high for the pain and function subscales on the AUSCAN and PRWHE, suggesting that items on each subscale consistently reproduce the same idea. High internal consistency for the total AUSCAN scale was also reported by Massy-Westropp et al.24 Our assessment of construct validity included a comparison of self-reported pain with the VRS pain measure. These results showed no particular difference in the association between these instruments’ pain and function subscales with hand strength and VRS pain measures (Table 4). Prior studies showed that the VRS pain measure was strongly correlated with the AUSCAN pain and function subscales1; our results demonstrated similar findings with both the PRWHE and AUSCAN. To support the criterion validity of the AUSCAN and PRWHE subscales, we compared self-reported function with objective measurements of strength; there was a low correlation between the 2 scales and hand strength, which was consistent with the results of MacDermid et al23 that these measures were only weakly associated.

The corresponding pain and function subscales of the AUSCAN and PRWHE (Tables 3 and 4) demonstrated the highest correlations, which are consistent with prior studies comparing the AUSCAN and PRWHE in a more advanced population of patients with CMC OA.23 Subtle differences between constructs such as pain interference and pain intensity on a given instrument, in addition to parallels between the 2 instruments themselves, may contribute to the high correlations observed between the subscores and total scores.

These scales were also assessed in a longitudinal manner by comparing the corresponding baseline and follow-up AUSCAN and PRWHE scores. The instruments demonstrate good correlation over the 2 time points; the changes in a participant’s PRWHE from baseline to follow-up were highly correlated with their changes in the AUSCAN. As the correlation between the change in an individual’s AUSCAN or PRWHE total score after 1.5 years is moderately high (r = 0.83, P < .01), this may indicate sufficient responsiveness of each to capture changes in rank order between patients. However, as the literature varies widely on the percentage of patients with early CMC OA who progress, it is difficult to assess how sensitive these instruments are to progression at this stage of the disease. This phenomenon of variability in disease progression is also evident in radiographic and biometric measurements.17 Future studies may utilize objective strength and radiographic measurements to further assess the sensitivity of these instruments in a selected cohort of OA patients with known progression.

The strengths of this study include equal male and female population and the longitudinal nature that allows comparison at baseline and a follow-up period. Given that the age and sex distribution of our cohort matches a sample of typical patients with early CMC disease, we believe these findings are generalizable to other populations. Limitations include incomplete follow-up data on our cohort (N = 83) due to patient relocation and progression to surgery, which may result in selection bias in the cohort of less pain and disability than expected at 1.5-year follow-up. Future studies with this cohort aim to evaluate progression at over 3 years.

Conclusions

This work supports that the AUSCAN and PRWHE demonstrate equal internal consistency, construct and criterion validity, and correlate strongly with each other in this cohort of patients with early thumb CMC OA. The AUSCAN is more commonly used in studies of OA, whereas the PRWHE is used for hand surgery/rehabilitation.4,22,23,26,28,30 The AUSCAN, however, is reportedly more difficult to score and has an associated annual license fee.4,23 This study suggests that these self-report instruments are comparable when assessing a patient with early CMC OA. The utility and feasibility of such instruments in the routine clinical setting depends on a variety of structural and patient-level factors. Further evaluation of new instruments that specifically address early thumb CMC OA, an intended future direction, will potentially assist in evaluating clinical and research utility.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: Amy L. Ladd has received stock from Articulinx LLC, Extremity Medical LLE, IlluminOss Medical; royalties from Extremity Medical and Orthohelix; and consultancy fees from Pacira. Arnold-Peter C. Weiss: Royalties from DePuy, Extremity Medical, Medartis, and stock in IlluminOss Medical. Joseph J. Crisco: Editor, Journal of Applied Biomechanics.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AR059185. Additional support (T.J.M.) was provided by the Stanford University School of Medicine MedScholars program.

References

- 1. Allen KD, DeVellis RF, Renner JB, et al. Validity and factor structure of the AUSCAN Osteoarthritis Hand Index in a community-based sample. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:830-836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Backman C, Mackie H. Reliability and validity of the arthritis hand function test in adults with osteoarthritis. Occup Ther J Res. 1997;17:55-66. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Becker SJ, Briet JP, Hageman MG, et al. Death, taxes, and trapeziometacarpal arthrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:3738-3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bellamy N, Campbell J, Haraoui B, et al. Dimensionality and clinical importance of pain and disability in hand osteoarthritis: development of the Australian/Canadian (AUSCAN) osteoarthritis hand index. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002;10:855-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bellamy N, Wilson C, Hendrikz J. Population-based normative values for the Australian/Canadian (AUSCAN) Hand Osteoarthritis Index: part 2. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:149-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berger AJ, Momeni A, Ladd AL. Intra- and interobserver reliability of the Eaton classification for trapeziometacarpal arthritis: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1155-1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chung KC, Pillsbury MS, Walters MR, et al. Reliability and validity testing of the Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire. J Hand Surg Am. 1998;23:575-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. De Smet L. The DASH questionnaire and score in the evaluation of hand and wrist disorders. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74:575-581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dias R, Chandrasenan J, Rajaratnam V, et al. Basal thumb arthritis. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:40-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eaton RG, Glickel SZ. Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. Staging as a rationale for treatment. Hand Clin. 1987;3:455-471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eaton RG, Littler JW. Ligament reconstruction for the painful thumb carpometacarpal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:1655-1666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gillis J, Calder K, Williams J. Review of thumb carpometacarpal arthritis classification, treatment and outcomes. Can J Plast Surg. 2011;19:134-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gummesson C, Atroshi I, Ekdahl C. The disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) outcome questionnaire: longitudinal construct validity and measuring self-rated health change after surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2003;4:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Halilaj E, Rainbow MJ, Got C, et al. In vivo kinematics of the thumb carpometacarpal joint during three isometric functional tasks. In Leopold SS. editor, Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. Vol.472; 2014:1114-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Halilaj E, Rainbow MJ, Moore DC, et al. In vivo recruitment patterns in the anterior oblique and dorsoradial ligaments of the first carpometacarpal joint. J Biomech. 2016;48:1893-1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, et al. Studies comparing numerical rating scales, verbal rating scales, and visual analogue scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:1073-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kwok WY, Plevier JWM, Rosendaal FR, et al. Risk factors for progression in hand osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65:552-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ladd AL, Messana JM, Berger AJ, et al. Correlation of clinical disease severity to radiographic thumb osteoarthritis index. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40:474-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ladd AL, Weiss APC, Crisco JJ, et al. The thumb carpometacarpal joint: anatomy, hormones, and biomechanics. Instr Course Lect. 2013;62:165-179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Luker KR, Aguinaldo A, Kenney D, et al. Functional task kinematics of the thumb carpometacarpal joint. In: Leopold SS. (ed) Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2014;472:1123-1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. MacDermid JC, Grewal R, MacIntyre NJ. Using an evidence-based approach to measure outcomes in clinical practice. Hand Clin. 2009;25:97-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. MacDermid JC, Tottenham V. Responsiveness of the disability of the arm, shoulder, and hand (DASH) and patient-rated wrist/hand evaluation (PRWHE) in evaluating change after hand therapy. J Hand Ther. 2004;17:18-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. MacDermid JC, Wessel J, Humphrey R, et al. Validity of self-report measures of pain and disability for persons who have undergone arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the carpometacarpal joint of the hand. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:524-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Massy-Westropp N, Krishnan J, Ahern M. Comparing the AUSCAN Osteoarthritis Hand Index, Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire, and Sequential Occupational Dexterity Assessment for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1996-2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McQuillan TJ, Kenney D, Crisco JJ, et al. Weaker functional pinch strength is associated with early thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:557-561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moe RH, Garratt A, Slatkowsky-Christensen B, et al. Concurrent evaluation of data quality, reliability and validity of the Australian/Canadian Osteoarthritis Hand Index and the Functional Index for hand osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2010;49:2327-2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(4):539-549. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Packham T, Macdermid JC. Measurement properties of the patient-rated wrist and hand evaluation: Rasch analysis of responses from a traumatic hand injury population. J Hand Ther. 2013;26:216-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Poiraudeau S, Chevalier X, Conrozier T, et al. Reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change of the Cochin hand functional disability scale in hand osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9:570-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Poole JL. Measures of hand function: Arthritis Hand Function Test (AHFT), Australian Canadian Osteoarthritis Hand Index (AUSCAN), Cochin Hand Function Scale, Functional Index for Hand Osteoarthritis (FIHOA), Grip Ability Test (GAT), Jebsen Hand Function Test (JHFT), and Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire (MHQ). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(suppl 11):S189-S199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Waljee JF, Kim HM, Burns PB, et al. Development of a brief, 12-item version of the Michigan Hand Questionnaire. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:208-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yao J, Park MJ. Early treatment of degenerative arthritis of the thumb carpometacarpal joint. Hand Clin. 2008;24:251-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]