Abstract

Background: Localized aortic dissection on the left coronary cusp with critical malperfusion of the left main trunk (LMT) is rare and carries a high risk of death.

Case presentation: We report a case of a 48-year-old patient who developed localized aortic dissection of the left coronary cusp complicated by critical malperfusion of the LMT of the coronary artery. After percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for the LMT, a Koster–Collins-like direct repair of the localized aortic dissection was carried out by closure of the false channel using BioGlue (CyroLife, Inc., Kennesaw, GA, USA) with the reinforcement of double Teflon felt strips.

Conclusion: The aortic repair using a modified Koster–Collins technique was successful.

Keywords: localized aortic dissection, malperfusion of left main trunk, direct repair

Introduction

Localized dissection of the ascending aorta is a rarely encountered aortic pathology. Severe compression of the left main trunk (LMT) of the coronary artery due to localized aortic dissection is extremely rare.1) Here, we describe a patient with acute localized ascending aortic dissection complicated by acute myocardial infarction (AMI) due to LMT compression, which was repaired by direct closure of the false channel of the localized aortic dissection at the left Valsalva sinus. The patient consented to participation and publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 48-year-old man with a history of hypertension and dyslipidemia was referred to our hospital due to a sudden onset of chest pain. An electrocardiogram revealed ST-segment elevation on leads I, aVL, and V1–V6 as well as ST-segment depression on leads II, III, and aVF. Echocardiography demonstrated severely impaired motion of the anterolateral wall of the left ventricle. Laboratory data revealed a white blood cell count of 19100/μL, a lactase dehydrogenase level of 213 IU/L, a creatinine kinase level of 77 mg/dL, a C-reactive protein level of 0.6 mg/dL, and a D-dimer level of 1.85 μg/mL. The examination results suggested AMI on the anterolateral wall of the left ventricle. Emergent coronary angiography was performed, revealing severe narrowing of the LMT (Fig. 1A). Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) guidance was then performed. The images of IVUS demonstrated an intimal flap extending from the aortic wall of the ascending aorta to the ostium of the LMT (Fig. 1B), which caused severe compression of the LMT ostium, leading to critical AMI. Following aortography also showed pooling of blood in the false channel of the localized aortic dissection. Immediately after that, the patient suddenly collapsed with sustained ventricular tachycardia. He was resuscitated with tracheal intubation and recovered with normal sinus rhythm. The 4.0 mm × 23 mm and 4.0 mm × 28 mm drug-eluting stents (XIENCE Alpine, Abbott Japan, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were placed from the LMT ostium to the left anterior descending (LAD) artery. However, severe hypotension persisted, and veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) through the femoral artery and vein was established. The patient was transferred to the operating room for emergency surgery.

Fig. 1. Coronary angiography and IVUS images. (A) Angiography showed severe stenosis at the site of the LMT. (B) IVUS images revealed the dissection flap (dotted lines) and visualized a hematoma from the aorta to throughout the length of the LMT. IVUS: intravascular ultrasound; LMT: left main trunk.

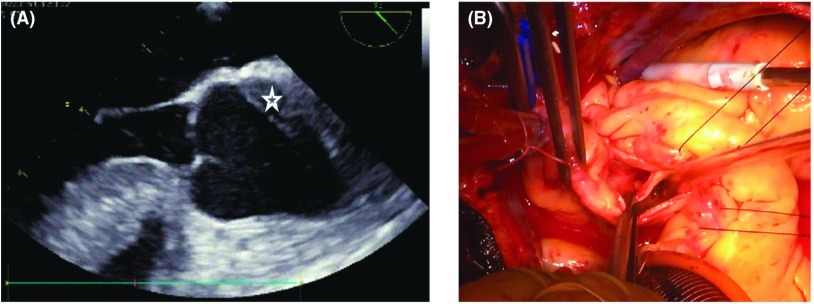

At surgery, the ascending aorta was exposed through a median sternotomy, but it was not enlarged and there were no signs of aortic dissection. A closer observation revealed a localized hematoma on the posterior wall of the ascending aorta. Trans-esophageal echocardiography showed localized dissection of the posterior wall of the aorta (Fig. 2A). Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) with tepid hypothermia (32°C) was established by means of cannulation of the ascending aorta and the right atrium. After aortic cross clamping with antegrade and retrograde cardioplegia, distal side coronary artery bypass grafting to the LAD and the circumflex branch using saphenous vein grafts (SVGs) was performed. After additional cardioplegic solution was given selectively from the SVGs, the dissecting part of the ascending aorta just above the sino-tubular junction was transversely opened. The inside of the ascending aorta showed some atherosclerotic changes. An entry was found at a 15-mm distal site above the LMT orifice. The LMT was also dissected (Neri’s classification type B) (Fig. 2B).2) The dissecting part of the aorta encompassed one-third the circumference of the ascending aorta and was localized at the left Valsalva sinus and a small part of the right Valsalva sinus and this caused the LMT compression. Instead of a standard graft replacement, the localized dissection was repaired by obliterating the false lumina at both ends using several mattress sutures of 4-0 Prolene with inside and outside felt strips attached with the aid of surgical glue (BioGlue). Both reinforced edges were closed with several horizontal mattress sutures followed by over-and-over sutures of 4-0 Prolene. Finally, proximal side coronary artery bypass grafting was performed. CPB time and aortic cross clamping time were 283 min and 172 min, respectively. Unfortunately, weaning from CPB was unsuccessful due to a severely impaired left ventricle caused by the AMI. It was eventually carried out with the support of VA-ECMO and intra-aortic balloon pumping (IABP). The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit with VA-ECMO and IABP. Perioperative laboratory data revealed a maximum creatine kinase level of 7712 U/L. Postoperative contrastenhanced computed tomography showed successful repair (Fig. 3). However, the patient’s cardiac dysfunction persisted 5 days after the operation, and he was transferred to a highly specialized hospital for implantation of a left ventricular assist device. Four months later, he died of severe sepsis.

Fig. 2. (A) Transesophageal echocardiography images. A hematoma (star sign) was detected from the left coronary cusp. (B) Intraoperative findings revealed a longitudinal intimal tear without a mobile intimal flap and a dissection 15 mm in length in the posterolateral wall of the left coronary cusp with a coronary false channel and implanted coronary stent.

Fig. 3. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography images. Postoperative contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed no extension of the aortic dissection, obliteration of the false channel, and patency of the coronary stents and bypass grafts.

Discussion

Localized aortic dissection of the ascending aorta is relatively rare. Its etiology may involve the interaction between cystic medial necrosis (CMN) and hypertension, as is the case with spontaneous rupture of the ascending aorta.3) Spontaneous aortic rupture occurs due to a perpendicular force to the outer membrane of the arterial wall through a crack over a small range of the inner membrane. In contrast, a crack with a similar small range of the inner membrane promotes a horizontal force against the arterial wall, which would result in localized aortic dissociation. As shown in our case, a crack with a similar small range of the inner membrane, which was caused by the interaction of weakened aortic wall due to CMN with excessive arterial pressures, occurred around the left sinus of Valsalva. Due to these mechanisms, the dissection seemed to be localized at the ascending aorta around the sino-tubular junction.

Patients with acute type A aortic dissection complicated with coronary artery malperfusion, in particular with malperfusion of the LMT, are at a very high risk of death. Coronary artery dissection is usually managed by replacement of the ascending aorta and reconstruction of the coronary artery.4) However, extensive myocardial infarction frequently occurs before coronary blood flow can be surgically reconstructed. For such cases, Imoto et al.5) recommended instead a more rapid placement of a coronary stent as the top priority to ensure blood flow in the LMT. However, in our case, despite the similar coronary intention, the cardiac function was not sufficiently restored, presumably because the myocardial ischemic damage was too extensive and prolonged to be repaired. Actually, the duration from the onset of aortic dissection to the coronary intervention was 4 hours. Quick diagnosis and decision-making are mandatory in the emergency treatment for acute type A aortic dissection, in particular, for cases with unstable hemodynamics. The surgical repair was also further delayed by 2 hours even under these conditions because of no available operating rooms for the emergency surgery.

In terms of the repair technique for localized aortic dissection, graft replacement of the dissecting aortic segment has become standard. However, in our case, the area of aortic dissection was localized to the one-third loop of the aorta just above the left coronary orifice, whereas the other aortic wall was not dissected. The graft replacement was rather more difficult because the aortic segment above the left coronary orifice was too short. Therefore, direct repair of the localized aortic dissection was carried out by closure of the false channel using BioGlue (CyroLife, Inc., Kennesaw, GA, USA) with the reinforcement of double (inside and outside) Teflon felt strips. Historically, Koster and Collins performed reinforcement of the dissected aortic wall using band-like felt in a false channel.6) In our case, BioGlue was used to close the false channel completely and reinforce the dissected aortic wall. We believed the blood flow of the left coronary artery was restored by such reliable techniques.

However, the patient’s cardiac function was not restored sufficiently to allow weaning from the circulatory support by IABP and VA-ECMO.

Conclusion

Critical malperfusion of the LMT of the coronary artery due to localized aortic dissection is extremely rare, and the repair technique is controversial. We successfully performed aortic direct repair using a modified Koster–Collins technique.

Disclosure Statement

None declared.

References

- 1).Masuyama S, Komiya T, Tamura N, et al. [Coronary malperfusion of left main trunk due to localized dissection of the ascending aorta]. Kyobu Geka 2007; 60: 433-7; discussion 437-40 (in Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Neri E, Toscano T, Papalia U, et al. Proximal aortic dissection with coronary malperfusion: presentation, management, and outcome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001; 121: 552-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Murray CA, Edwards JE. Spontaneous laceration of ascending aorta. Circulation 1973; 47: 848-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Motallebzadeh R, Batas D, Valencia O, et al. The role of coronary angiography in acute type A aortic dissection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2004; 25: 231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Imoto K, Uchida K, Suzuki S, et al. Stenting of a left main coronary artery dissection and stent-graft implantation for acute type A aortic dissection. J Endovasc Ther 2005; 12: 258-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Koster JK, Cohn LH, Mee RB, et al. Late results of operation for acute aortic dissection producing aortic insufficiency. Ann Thorac Surg 1978; 26: 461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]