Abstract

Purpose

Retinoblastoma (RB) is a retinal tumor that most commonly occurs in children. Approximately 40% of RB patients carry germline mutations in the RB1 gene. RB survivors with germline mutations are at increased risk of passing on the disease to future offspring and of secondary cancer in adulthood. This highlights the importance of genetic testing in disease management and counseling. This study aimed to identify germline RB1 mutations and to correlate the mutations with clinical phenotypes of RB patients.

Methods

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from 52 RB patients (27 unilaterally and 25 bilaterally affected probands). Mutations in the RB1 gene, including the promoter and exons 1–27 with flanking intronic sequences, were identified by direct sequencing. The samples with negative test results were subjected to multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) to detect any gross mutations. A correlation of germline RB1 mutations with tumor laterality or age at diagnosis was determined for RB patients. Age at diagnosis was examined in regard to genetic test results and the presence of extraocular tumor extension.

Results

Germline RB1 mutations were detected in 60% (31/52) of patients. RB1 mutations were identified in 92% (22/25) of bilateral RB patients, and a high rate of germline RB1 mutations was found in unilateral RB cases (33% or 9/27). Whole gene and exon deletions were reported in five patients. Twenty-three distinct mutations as a result of base substitutions and small deletions were identified in 26 patients; seven mutations were novel. Nonsense and splicing mutations were commonly identified in RB patients. Furthermore, a synonymous mutation was detected in a patient with familial RB; affected mutation carriers in this family exhibited differences in disease severity. The types of germline RB1 mutations were not associated with age at diagnosis or laterality. In addition, patients with positive and negative test results for germline RB1 mutations were similar in age at diagnosis. The incidence of extraocular tumors was high in patients with heritable RB (83% or 5/6), particularly in unilateral cases (33% or 3/9); the mean age at diagnosis of these patients was not different from that of patients with intraocular tumors.

Conclusions

This study provides a data set of an RB1 genotypic spectrum of germline mutations and clinical phenotypes and reports the distribution of disease-associated germline mutations in Thai RB patients who attended our center. Our data and the detection methods could assist in identifying a patient with heritable RB, establishing management plans, and informing proper counseling for patients and their families.

Introduction

Retinoblastoma (RB) is a retinal tumor of infancy and childhood that is initiated upon biallelic loss of the RB1 gene, a tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 13. In the dominantly inherited form, one mutant allele is inherited through the germinal cells, thus affecting all cells in the adult. The other mutation occurs in the retinal cells, which undergo malignant transformation [1]. Patients with germline RB1 mutations account for 35%–45% of all RB cases and often have bilateral RB; 10%–15% of cases with germline mutations have unilateral RB and therefore have the heritable form of this disease [2]. Probands with heritable RB can transfer pathogenic variants to offspring, thus increasing the risk of passing on the disease. In addition, patients with germline mutations in the RB1 gene are at high risk of subsequent non-ocular primary tumors throughout their lives, including bone tumor, soft-tissue sarcoma, and skin melanoma, which necessitates clinical follow-up and counseling for patients and their families [3].

In Thailand, approximately 35–40 patients are diagnosed with RB each year; these cases are often diagnosed at less than four years of age. The disease equally affects males and females and has a five-year survival rate of 73.1% [4]. RB survivors require intensive eye examination under anesthesia, particularly for younger patients, to monitor for recurrent or new tumors. This monitoring is costly and subjects children to medical risks [5]. Genetic testing for RB1 mutations assists in establishing an appropriate surveillance plan and thus reduces the need for costly screening procedures for family members who have not inherited the pathogenic variant. The testing can confirm the presence of familial pathogenic variants, allowing for early identification of RB that may occur in at-risk relatives. Test results can further inform genetic counseling for affected families [6].

However, genetic testing and data sets with regard to germline RB1 mutations in RB patients have not yet been reported from Thailand. In this study, we aimed to identify germline RB1 mutations in RB patients using direct sequencing in combination with multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA). We further correlated clinical phenotypes with RB1 mutations and both positive and negative test results. This study provides data sets of germline RB1 mutations and clinical phenotypes that could assist in identifying a patient with heritable RB, establishing management plans, and informing proper counseling for RB patients.

Methods

Blood samples

All Thai RB patients (52 patients) presenting between 2008 and 2018 at our center were recruited for blood collection. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University (protocol number ID07–60–14). All methods were performed in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology. Informed consent was obtained from a parent of each patient before the samples were collected.

DNA and RNA extraction

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from blood with Ficoll®-Paque Plus reagent (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Genomic DNA was extracted with the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and total RNA was extracted using TriPure isolation reagent (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), both in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA quality was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The concentrations of DNA and RNA were measured with a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer.

Genetic analysis

The RB1 gene, including the promoter and exons 1–27 with flanking intronic sequences, were amplified using 26 pairs of specific primers (Appendix 1). The PCR reaction was performed in a total volume of 25 μl containing 25 ng genomic DNA, 0.5 μM primers, and 1X AmpliTaq Gold 360 master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Touchdown PCR was used for amplification of all regions except exons 11, 13, and 24, which were amplified using a specific condition (Appendix 1). Touchdown PCR was conducted with initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min and then 10 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 67–57 °C for 30 s (1 °C decreased each cycle), and extension at 72 °C for 1 min. This was followed by 25 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 57 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension step at 72 °C for 7 min. The reactions were held at 15 °C until collection. Exons 11, 13, and 24 were amplified using initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min and then 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58 °C (for exon 11) or 61 °C (for exons 13 and 24) for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. The final extension step was at 72 °C for 7 min, and reactions were held at 15 °C until collection. The PCR products were confirmed using agarose gel electrophoresis and purified with illustra ExoProStar 1-Step™ (GE Healthcare, Freiburg, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing reactions were prepared using the BigDye® Terminator kit (Applied Biosystems). PCR products were then sequenced with the 3730XL sequencer (Applied Biosystems) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The samples with negative test results were subjected to MLPA to detect gross mutations. MLPA was conducted using the SALSA MLPA P047-D1 RB1 probe mix (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The reactions were loaded on a capillary electrophoresis device, and the results were analyzed using Coffalyser.Net software (MRC-Holland).

Reverse transcription PCR

First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA with ImProm-II reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI) and random primers in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was subjected to touchdown PCR (using the condition used for genetic analysis); specific PCR primers are listed in Appendix 1. RT–PCR products were purified using a gel extraction kit (Qiagen) for sequencing.

Data analysis of RB1 variants

Sequencing chromatograms were analyzed using Mutation Surveyor software (SoftGenetics, State College, PA); the sequence of the RB1 gene (accession number L11910) was used as reference. The RB1 gene mutations were verified with the rb1-lsdb database, the Human Gene Mutation Database, ClinVar, InterVar, and Exome Aggregation Consortium. The pathogenicity of genetic variants was further predicted using online bioinformatics tools, as follows. Human Splicing Finder, MaxENtScan, and Spliceman were used to predict the pathogenicity of splice variants. MutPred2, PolyPhen-2, PROVEAN, SIFT, and Mutation Taster were used to predict the pathogenicity of missense variants. MutPred2 and Mutation Tester were used to predict the pathogenicity of frameshift mutations. MUpro, iPTREE-STAB, and iStable were used to predict protein stability changes upon single amino acid mutations. Sequence in FASTA format was obtained from the NCBI database (NP_000312.2) for structure prediction of RB1 protein. Model structures of wild-type and mutants (missense variant) were created in Swiss-pdb Viewer; the wild-type and mutant-equivalent models were analyzed using the ANOLEA server. All variants were deposited in Global Variome shared LOVD.

Statistics

A Welch’s t test was used to test for the differences in mean age at diagnosis with regard to genetic test results (negative and positive) and laterality. A one-way ANOVA was used to test for the differences in mean age at diagnosis with respect to mutation types and the presence of extraocular extension in patients with heritable RB. A Fisher’s exact test was used to determine the association between mutation types and tumor laterality.

Results

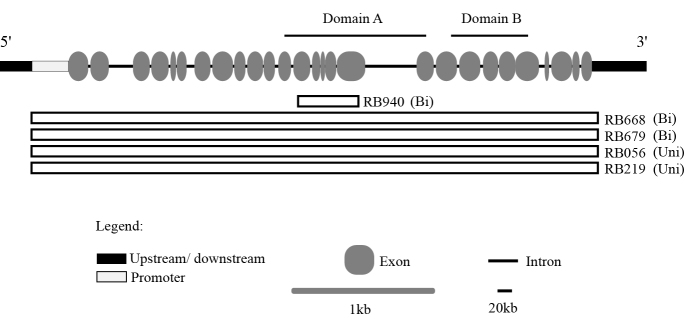

Fifty-two patients diagnosed with RB were recruited for genetic testing for germline RB1 mutations. Of these patients, 25 (48%) were affected bilaterally, and 27 (52%) were affected unilaterally. Direct sequencing detected germline RB1 mutations in 26 of the 52 patients (Table 1). Samples with negative test results (from 26 patients) were subjected to MLPA to identify any gross mutations that could not be detected using the direct sequencing. MLPA revealed gross deletions in the RB1 gene in five patients (Figure 1). Thus, germline RB1 mutations were detected in 31 of the 52 patients (Table 1 and Figure 1). These analyses showed that the combination of direct sequencing and MLPA improved the sensitivity of detection from 50% (26/52) to 59.6% (31/52; Table 1 and Figure 1). Germline mutations were identified in approximately one-third of unilateral RB cases (33% or 9/27) and most bilateral RB cases (92% or 22/25; Figure 1 and Table 1). Twenty-three distinct mutations were detected by PCR sequencing; seven were novel mutations and included splicing (1), frameshift (3), missense (2), and promoter (1) mutations (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of germline RB1 mutations (small-scale mutations) identified in retinoblastoma patients.

| ID | Location | DNA variation | Expected consequence | phenotype | Times found in rb1-lsdb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RB294# | Ex 18 | g.150037C>T | p.Arg579* | Bi | 94 |

| RB581# | Ex 18 | g.150037C>T | p.Arg579* | Bi | 94 |

| RB630## | Ex 14 | g.76460C>T | p.Arg455* | Bi | 62 |

| RB683## | Ex 14 | g.76460C>T | p.Arg455* | Bi | 62 |

| RB414 | Ex 4 | g.41954G>T | p.Glu137* | Bi | 10 |

| RB488 | Ex 23 | g.162237C>T | p.Arg787* | Bi | 68 |

| RB047 | Ex 22 | g.162021G>T | p.Glu746* | Uni | 4 |

| RB988 | Ex 14 | g.76430C>T | p.Arg445* | Bi | 79 |

| RB654 | Ex 17 | g.78250C>T | p.Arg556* | Bi | 49 |

| RB960 | In 24 | g.170405_170408del | Splice | Bi | 10 |

| RB140 | In 19 | g.156692G>C | Splice | Bi | Novel$ |

| RB231 | In 15 | g.76921G>A | Splice | Bi | 2 |

| RB410$$ | Ex 2 | g.5550G>A | Splice | Familial Bi | 3 |

| RB851 | In 21 | g.160835G>A | Splice | Bi | 1 |

| RB844 | In 9 | g.61808G>A | Splice | Uni | 1 |

| RB453 | In 6 | g.45867G>T | Splice | Uni | 21 |

| RB709 | Ex 1 | g.2151_2152del | p.Glu31Glyfs*17 | Uni | Novel |

| RB037 | Ex 10 | g.64395del | p.Leu335Phefs*14 | Bi | 1 |

| RB339 | Ex 18 | g.150044del | p.Gly581Aspfs*30 | Bi | Novel |

| RB103 | Ex 15 | g.76896del | p.Glu466Aspfs*12 | Bi | Novel |

| RB723 | Ex 1 | g.2142C>G | p.Pro28Arg | Uni | Novel |

| RB380 | Ex 20 | g.156704G>C | p.Ala658Pro | Bi | Novel$ |

| RB150 | Ex 21 | g.160740G>A | p.Cys706Tyr | Bi | 2 |

| RB680 | Promoter | g.1862G>A | - | Bi | 5 |

| RB214### | Promoter | g.1825G>A | - | Uni | Novel |

| RB187### | Promoter | g.1825G>A | - | Uni | Novel |

The numbering of DNA and amino acid sequences refers to the reference sequences of accession number L11910 and NP_000312, respectively. $Point mutation has the identical genomic position reported in the RB1 locus specific database (RB1-lsdb.d-lohmann.de/) but is substituted with a different nucleotide. $$One case with familial RB found in this study. #, ##, ### patients have the identical mutation. Abbreviations: Ex, Exon; In, Intron; Bi, bilateral RB; Uni, Unilateral RB.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of gross deletions in the RB1 gene in patients with retinoblastoma. The promoter and exons 1–27 with flanking intronic sequences of RB1 are depicted; domain A and domain B and coding for the binding domain A/B pocket are shown. Bars represent partial (exons 13–17 in RB940) and whole gene (RB668, RB679, RB056, and RB219) deletions. Abbreviations: Uni, unilateral RB; Bi, bilateral RB.

In silico pathogenicity analysis indicated that these novel variants (splice, missense, and frameshift) were associated with diseases (Table 2). In addition, protein stability changes were predicted based on single amino acid mutations (Table 2). The results suggested that as a result of missense variants, p.Ala658Pro (RB380) and p.Pro28Arg (RB723) decreased the stability of RB1 protein; the effect was less damaging for p.Pro28Arg compared to p.Ala658Pro, agreeing with tumor laterality (Table 1 and Table 2). Furthermore, molecular modeling (data analyzed using the Swiss-pdb Viewer available only for p.Ala658Pro) of the RB1 predicted that p.Ala658Pro impairs the energy required to maintain the proper folding of helices α11, α12, and α14 of domain B of the A/B pocket, possibly causing global destabilization of the RB1 structure (Appendix 1). The novel mutation in the promoter element was detected in two unrelated patients (RB214 and RB187); a genomic position of this variant is predicted to associate with the initiation site of RB1 transcription [7] (Table 1).

Table 2. In silico pathogenicity analysis of novel RB1 variants and prediction of protein stability changes upon single amino acid mutations.

| Cases | Mutation types | Prediction of pathogenicity |

Prediction of protein stability change |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MutPred2 | MutationTaster | Polyphen-2 | SIFT | PROVEAN | Human Splicing Finder | MaxEntScan | MUpro | iPTREE-STAB | iStable | ||

| RB723 | MS | Disease-associated | Disease causing | Benign | Damaging | Neutral | - | - | Decreased stability | Stabilizing | Destabilizing |

| RB380 | MS | Disease-associated | Disease causing | Probably damaging | Damaging | Deleterious | - | - | Decreased stability | Destabilizing | Destabilizing |

| RB709 | FS | Pathogenic | Disease causing | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RB103 | FS | Pathogenic | Disease causing | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RB339 | FS | Pathogenic | Disease causing | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RB140 | SP | - | - | - | - | - | Broken WT acceptor site | Broken splice site | - | - | - |

Novel variant in promoter region detected in RB214 and RB187 involves transcriptional initiation site [7]. Abbreviations: MS, missense; FS, frameshift; SP, splicing; WT, wild-type.

Nonsense mutations (28%) were the most frequently detected mutation and were associated with CpG transitions (Table 3). The identical nonsense mutation in exon 14 was detected in two unrelated patients; a similar finding was revealed for the mutation in exon 18 (Table 1). The second most common mutation type was splicing error (25%), in which a base substitution reduced the consensus homology at the splice junctions. Frameshift (13%), missense (9%), and promoter (9%) mutations were detected less frequently in our cohort (Table 3). Two discrete clusters of “hot spot” mutations were identified, accounting for 71% (22/31) of patients with germline mutations. The first cluster comprised the mutations in exons 14–24 with flanking intronic sequences (51.6% of cases), and the second comprised the mutations in the promoter region and exons 1 and 2 (19.4% of cases; Table 1). Mutations in exons 14 and 18 and the promoter element were frequently found in our patients (Table 1). Furthermore, the detection of whole (four patients) and partial (one patient) RB1 gene deletions indicated that 16% of patients with germline mutations had gross RB1 gene deletions (Figure 1 and Table 3).

Table 3. Clinical profiles of RB patients with different types of germline RB1 mutations.

| Mutation type | Number of probands | Mean age at diagnosis months (±SEM) |

Number of probands

by lateral type |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unilateral | Bilateral | |||

| Nonsense# | 9 (28%) | 7.3 (2.5) | 1 | 8 |

| Splicing## | 7 (25%) | 11.9 (3.7) | 2 | 5 |

| Frameshift# | 4 (13%) | 16.5 (10.9) | 1 | 3 |

| Missense## | 3 (9%) | 3.7 (1.5) | 1 | 2 |

| Promoter## | 3 (9%) | 21.0 (4.0) | 2 | 1 |

| Gross deletion |

5 (16%) |

17.4 (6.4) |

2 |

3 |

| Total | 31 | 9 | 22 | |

Mean age at diagnosis is not different among patients with different types of mutations by One-way ANOVA. Laterality is not associated with mutation types (testing for patients with mutations that resulted in premature stop codon: #nonsense and #frameshift mutations versus patients with ##splicing mutations combined with those with ##missense and with ##promoter mutations by Fisher’s exact test).

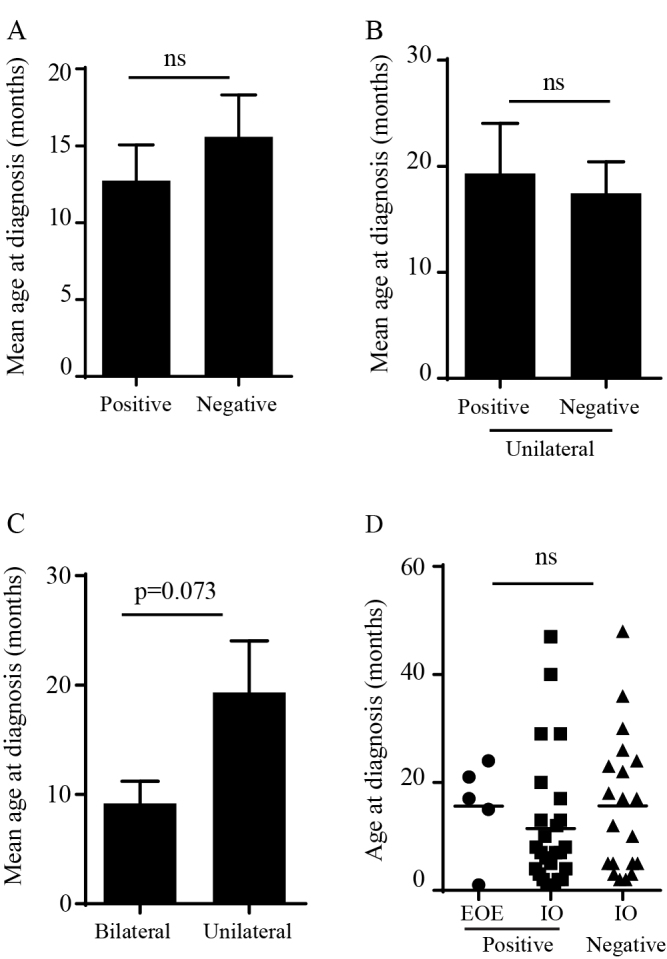

The age at diagnosis of probands with heritable RB ranged from 1–47 months, with a mean age at diagnosis of 12.1±2.1 months (mean±SEM). This was not statistically different from the mean age at diagnosis of patients whose genetic testing was negative (15.6±2.7 months; Figure 2A). Furthermore, unilateral RB patients with regard to the test results had a similar age at diagnosis (19.3±4.7 and 17.4±3.0 months for patients with positive and negative test results, respectively; Figure 2B). Of the patients with heritable RB, the mean age at diagnosis of bilateral RB patients was younger than that of unilateral RB cases (9.2±2.0 versus 19.3±4.7 months, p=0.073, Welch’s t test; Figure 2C). Nonsense, splicing, and missense mutations were detected in patients with a mean age at diagnosis of less than 12 months, while other types of mutations were found in older patients (Table 3). Nevertheless, the mean age at diagnosis was not statistically different in patients with different mutation types (one-way ANOVA; Table 3). In addition, we found that tumor laterality was not associated with the types of mutations (testing for patients with mutations that resulted in a premature stop codon: nonsense and frameshift versus patients with spicing, missense, and promoter mutations based on a Fisher’s exact test; Table 3).

Figure 2.

Clinical phenotypes of retinoblastoma patients with positive and negative test results for germline RB1 mutations. A: Age at diagnosis of probands with positive (n=31) or negative (n=21) test results. B: Age at diagnosis of unilateral RB patients who tested positive (n=9) or negative (n=18) for germline mutations. C: Age at diagnosis of probands with heritable RB affected bilaterally (n=22) or unilaterally (n=9). Data shown are mean±SEM, Welch’s t test. D: Age at diagnosis of probands with extraocular extension (EOE; positive test results, n=5) compared with that of probands with intraocular (IO) tumors (positive test results, n=26; negative test results, n=20). Data shown are mean±SEM, one-way ANOVA. ns: not significant.

We found that our patients generally had advanced RB; 25.5% and 56.9% of eyes were classified into groups D and E, respectively (according to the International Classification of Retinoblastoma; Table 4). Six cases presented with extraocular tumor extension, five of which had heritable RB, accounting for 16.1% (5/31) of cases with germline mutations and 5.0% (1/20) of patients with negative test results (Table 4). Intriguingly, the mean age at diagnosis of patients who had germline mutations and extraocular tumor extension (15.3±3.2 months) was similar to that of patients with intraocular disease (11.5±2.4 months for a patient with a positive test result and 15.6±2.9 months for a patient with a negative test result; Figure 2D). The incidence of extraocular tumor extension was high in unilateral RB cases with germline mutations (33% or 3/9) compared to bilateral RB cases (9% or 2/22; Table 4). Mutations identified in these patients included gross deletions (RB056 and RB219), base substitution in the promoter element (RB214), and nonsense mutations (RB683 and RB630).

Table 4. Classification of RB in patients with positive and negative test results for germline RB1 mutations detected by direct sequencing in combination with MLPA.

| Detection | Mutation type | No. of eyes |

Number of eyes in ICRB stages |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | Ex | |||

| Positive |

Nonsense | 9 | - | 1 | - | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Splicing | 7 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 5 | - | |

| Frameshift | 4 | - | - | - | 2 | 2 | - | |

| Missense | 3 | - | 1 | - | - | 2 | - | |

| Promoter | 3 | - | - | - | - | 2 | 1 | |

| Gross deletion | 5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

2 |

|

| |

31 |

- |

2

(6.5%) |

1

(3.2%) |

5 (16.1%) |

18

(58.1%) |

5

(16.1%) |

|

| Negative |

|

20# |

- |

- |

- |

8

(40.0%) |

11

(55.0%) |

1

(5.0%) |

| Total | 51 | - | 2 (3.9%) | 1 (1.9%) | 13 (25.5%) | 29 (56.9%) | 6 (11.8%) | |

Tumor exhibiting more advanced stage in one eye than the other is reported for bilateral patients. #Data of one patient with a negative test result were not available. Abbreviation: Ex, extraocular RB.

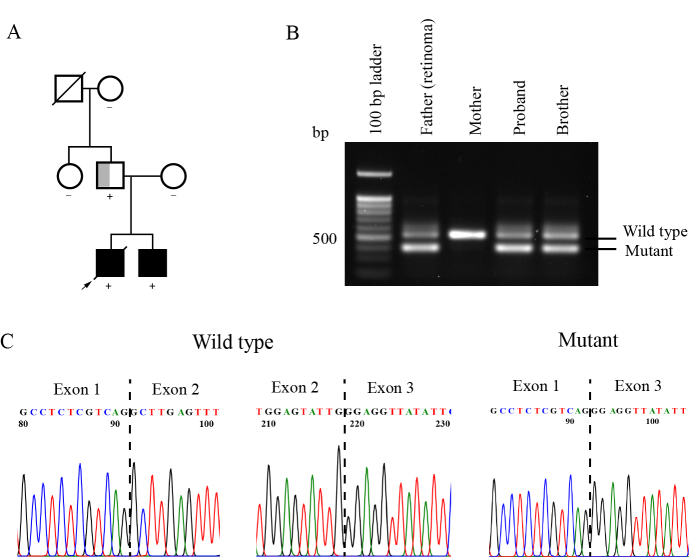

We found familial RB in one case; the male proband was diagnosed with bilateral RB at 20 months of age (Figure 3A). The younger brother of the proband similarly had bilateral RB that was diagnosed at two months of age. In addition, their father had retinoma in one eye and phthisis bulbi in the other eye. The diseased-eye ratio of this family was at least 1.67 (5/3), indicating complete disease penetrance. This suggested that any sibling carrying this pathogenic variant had a high risk of RB. Molecular analysis of the RB1 gene revealed that the father and his children had a synonymous mutation at the last nucleotide of exon 2 [g.5550 G>A (p.Leu88Leu)]; in silico pathogenicity analysis predicted that this variant caused a splicing error. RT–PCR using a single primer pair allowed the simultaneous detection of two distinguishable amplicons of wild-type and mutant transcripts; amplicon sequencing revealed that this mutation resulted in the exclusion of exon 2 (Figure 3B,C). The transcript levels of the mutant allele were relatively higher than those of the wild-type allele in blood cells (RT–PCR products were quantified using Image J software; NIH).

Figure 3.

A synonymous mutation detected in affected family members with retinoblastoma or retinoma. A: Family pedigree illustrating the inheritance pattern within a family. Affected family members carried a synonymous mutation (g.5550 G>A, p.Leu88Leu). The proband (arrow) and his brother had bilateral RB (solid black), whereas their father had unilateral retinoma (half gray). The diagonal line represents deceased, and the + or – indicates the presence or absence of an RB1 pathogenic variant. B: Mutant and wild-type transcripts detected in blood cells of affected mutation carriers. C: Chromatograms of RT–PCR products show the absence of exon 2 in mutant RB1 transcripts.

Discussion

This study reports heterozygous germline RB1 mutations in 31 of 52 RB cases; one case had familial RB. Most of the germline mutations (84%) in the RB1 gene involve one or a few nucleotides; the types of mutations were not associated with mean age at diagnosis or tumor laterality. The remaining mutations involve gross alterations in the RB1 gene. We found that the germline mutation rate was high in unilateral RB patients and in patients with extraocular tumors.

Direct sequencing in conjunction with MLPA increased the sensitivity of detection compared to direct sequencing alone and detected germline RB1 mutations in 59.6% of patients. This is in the range of the reported rates of 42-67% [8-12]. The combined methods detected germline mutations in 92% of bilaterally affected probands, which is consistent with previous reports (88.8%–100%) using identical screening strategies [8-12]. Bilaterally affected probands usually have heritable RB and therefore are expected to test positive for a mutation in the RB1 gene. However, undetectable mutations in these bilateral RB cases could be due to the presence of low-level mosaic (<20% of mutant alleles) [13] or deep intronic variants that cannot be detected by direct sequencing. Low-level mosaicism has been identified in 5.5% of bilateral RB cases through allele-specific PCR of 11 mutational “hot spots” [14]; however, this strategy does not rule out other unknown patient-specific mosaic variants. Without prior knowledge of mutant alleles, next-generation deep sequencing or targeted next-generation sequencing of the RB1 gene can detect low-level mosaic variants at a frequency between 8% and 24% in blood DNA [15,16]. However, next-generation sequencing is costly relative to direct sequencing and is therefore preferable only if mutations are not identified using direct sequencing and MLPA.

The combined methods revealed that 33% (9/27) of unilateral RB patients had heritable RB; this incidence is high compared with that of previous reports (between 8.7% and 25%) using identical screening strategies [8-12]. We found that the mean age at diagnosis was similar between unilateral RB patients with positive and negative test results, suggesting that age is not a factor to exclude patients from genetic testing. Indeed, genetic testing is recommended for all patients with unilateral RB. Previous studies have reported that extraocular tumor extension is often identified in unilateral RB cases [17,18], although the studies do not examine whether these patients with extraocular tumors have germline RB1 mutations. A similar finding was revealed in our study. Previous reports also suggest that delayed diagnosis is a risk factor for the presence of extraocular tumor extension at initial diagnosis, usually at a mean age of more than 3.5 years [17-19]. In our study, the mean age at diagnosis of patients with extraocular tumor extension was as early as 15 months and was similar to that of patients with intraocular tumors. This is because patients with extraocular extension had germline RB1 mutations that are responsible for the early initiation of disease; RB is therefore identified at a young age. There is one case with heritable RB where tumors with extraocular extension were diagnosed at one month of age (and at initial examination); this also supports the notion that the onset of the disease occurs in the uterus.

The mortality linked to extraocular extension is high [20]. By detecting germline mutations early in at-risk siblings and relatives, frequent and detailed eye examinations can be regularly performed to monitor for the disease. If tumors are found, proper treatments can be initiated to prevent advanced disease. In addition, a higher rate of mortality has been documented for heritable RB patients during the follow-up period due to second primary cancers compared with non-heritable RB patients [21,22]. It is therefore important to define whether patients have germline RB1 mutations to enable proper management, including clinical follow-up for the early detection and treatment of subsequent non-ocular primary tumors.

Nonsense mutations are most frequently identified in patients with heritable RB and are associated with bilateral RB [9-12,23,24], which is consistent with our results. We found that splicing mutations were commonly identified in our patients compared with RB patients in other Asian countries [8-10,12,23,24]. Previous observations suggest that splicing errors are associated with delayed onset phenotypes (older age at diagnosis) compared with nonsense, frameshift, and missense mutations [25]. However, we did not find this association, which is consistent with a previous report from Israel [24]. We found a synonymous mutation that resulted in the skipping of exon 2 in transcripts. A report of this mutation has been published once for a sporadic, bilateral RB case [26]. We also found that this synonymous mutation was present in family members who had retinoma or bilateral RB. The formation of retinoma requires biallelic loss of RB1, but non-proliferative cells, a low level of genomic disruption, and the high expression of senescence-associated proteins identified in retinoma can result in reduced severity of the disease [27]. In addition, it is interesting to note that the levels of mutant mRNAs through transcriptional or post-transcriptional regulation may be partly responsible for the differential penetration of disease [28]. Our study reported that a high penetration of familial RB is associated with a higher abundance of mutant transcripts compared with wild-type transcripts in the blood cells of affected mutation carriers. Our data support a previous finding showing that incomplete penetration of disease in affected families is associated with the relative abundance of mutant transcripts at levels either similar to or considerably lower than the transcript level of the wild-type allele in blood cells [28]. However, quantitative analysis such as RT-qPCR or droplet digital RT–PCR is required to confirm the relative abundance of wild-type and mutant transcripts detected in our study; PCR efficiency and internal controls need to be established for the detection of both transcript variants [29].

Genetic testing for germline RB1 mutations benefits all RB patients and their families. The discovery of germline mutations in probands can confirm whether the pathogenic variants are present in family members. This helps patients and their family members who will truly benefit from intensive eye examinations and life-long follow-up, while excluding unnecessary costly screening procedures for those who have not inherited pathogenic variants. If RB is a familial disorder, early detection of RB1 mutations in siblings and relatives of probands could prompt detailed eye examinations and frequent follow-up schedules, allowing for the early detection and treatment of RB (if present). The detection of germline mutations in the RB1 gene also increases awareness of the personal risk of secondary cancers during adulthood for survivors. Knowledge of germline mutations also helps inform counseling for affected families, including prenatal diagnosis or preimplantation genetic diagnosis with in vitro fertilization to avoid passing on RB1 pathogenic variants to future offspring.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who donated material to this project, as well as the clinical teams that made this project possible. We thank Dr. Donniphat Dejsuphong for facilitating the accessibility to the Mutation Surveyor software. This work was financially supported by Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital [CF_60002 and RF_59030], Thailand Research Fund [MRG 5980031], Talent Management Grant (under MU), Mahidol University and Children Cancer Fund under the patronage of HRH Princess Soamsawali and Ramathibodi Foundation for conducting the research.

Appendix 1. Supplementary information.

To access the data, click or select the words “Appendix 1.”

References

- 1.Vogel F. Genetics of retinoblastoma. Hum Genet. 1979;52:1–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00284597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knudson AG., Jr Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:820–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacCarthy A, Bayne AM, Brownbill PA, Bunch KJ, Diggens NL, Draper GJ, Hawkins MM, Jenkinson HC, Kingston JE, Stiller CA, Vincent TJ, Murphy MFG. Second and subsequent tumours among 1927 retinoblastoma patients diagnosed in Britain 1951–2004. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:2455–63. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiangnon S, Veerakul G, Nuchprayoon I, Seksarn P, Hongeng S, Krutvecho T, Sripaiboonkij N. Childhood cancer incidence and survival 2003–2005, Thailand: study from the Thai pediatric oncology group. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:2215–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batra R, Abbott J, Jenkinson H, Ainsworth John R, Cole T, Parulekar Manoj V, Kearns P. Long‐term retinoblastoma follow‐up with or without general anaesthesia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:260–4. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soliman SE, Racher H, Zhang C, MacDonald H, Gallie BL. Genetics and molecular diagnostics in retinoblastoma–An update. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2017;6:197–207. doi: 10.22608/APO.201711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong FD, Huang HJ, To H, Young LJ, Oro A, Bookstein R, Lee EY, Lee WH. Structure of the human retinoblastoma gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5502–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahani A, Behnam B, Khorshid HR, Akbari MT. RB1 gene mutations in Iranian patients with retinoblastoma: report of four novel mutations. Cancer Genet. 2011;204:316–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He MY, An Y, Gao YJ, Qian XW, Li G, Qian J. Screening of RB1 gene mutations in Chinese patients with retinoblastoma and preliminary exploration of genotype- phenotype correlations. Mol Vis. 2014;20:545–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohd Khalid MK, Yakob Y, Md Yasin R, Wee Teik K, Siew CG, Rahmat J, Ramasamy S, Alagaratnam J. Spectrum of germ-line RB1 gene mutations in Malaysian patients with retinoblastoma. Mol Vis. 2015;21:1185–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parma D, Ferrer M, Luce L, Giliberto F, Szijan I. RB1 gene mutations in Argentine retinoblastoma patients. Implications for genetic counseling. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0189736. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomar S, Sethi R, Sundar G, Quah TC, Quah BL, Lai PS. Mutation spectrum of RB1 mutations in retinoblastoma cases from Singapore with implications for genetic management and counselling. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0178776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Z, Moran K, Richards-Yutz J, Toorens E, Gerhart D, Ganguly T, Shields CL, Ganguly A. Enhanced sensitivity for detection of low-level germline mosaic RB1 mutations in sporadic retinoblastoma cases using deep semiconductor sequencing. Hum Mutat. 2014;35:384–91. doi: 10.1002/humu.22488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rushlow D, Piovesan B, Zhang K, Prigoda-Lee NL, Marchong MN, Clark RD, Gallie BL. Detection of mosaic RB1 mutations in families with retinoblastoma. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:842–51. doi: 10.1002/humu.20940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amitrano S, Marozza A, Somma S, Imperatore V, Hadjistilianou T, De Francesco S, Toti P, Galimberti D, Meloni I, Cetta F, Piu P, Di Marco C, Dosa L, Lo Rizzo C, Carignani G, Mencarelli MA, Mari F, Renieri A, Ariani F. Next generation sequencing in sporadic retinoblastoma patients reveals somatic mosaicism. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:1523–30. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devarajan B, Prakash L, Kannan TR, Abraham AA, Kim U, Muthukkaruppan V, Vanniarajan A. Targeted next generation sequencing of RB1 gene for the molecular diagnosis of retinoblastoma. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:320. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1340-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chawla B, Hasan F, Azad R, Seth R, Upadhyay AD, Pathy S, Pandey RM. Clinical presentation and survival of retinoblastoma in Indian children. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100:172–8. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaliki S, Patel A, Iram S, Ramappa G, Mohamed A, Palkonda VAR. Retinoblastoma in India: clinical presentation and outcome in 1,457 patients (2,074 Eyes). Retina. 2017;••• doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sethi S, Pushker N, Kashyap S, Sharma S, Mehta M, Bakhshi S, Khurana S, Ghose S. Extraocular retinoblastoma in Indian children: clinical, imaging and histopathological features. Int J Ophthalmol. 2013;6:481–6. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2013.04.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antoneli CB, Steinhorst F, de Cassia Braga Ribeiro K, Novaes PE, Chojniak MM, Arias V, de Camargo B. Extraocular retinoblastoma: a 13-year experience. Cancer. 2003;98:1292–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu CL, Tucker MA, Abramson DH, Furukawa K, Seddon JM, Stovall M, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Kleinerman RA. Cause-specific mortality in long-term survivors of retinoblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:581–91. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghassemi F, Chams H, Sabour S, Karkhaneh R, Farzbod F, Khodaparast M, Vosough P. Characteristics of germline and non-germline retinoblastomas. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2014;9:188–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalsoom S, Wasim M, Afzal S, Shahzad MS, Ramzan S, Awan AR, Anjum AA, Ramzan K. Alterations in the RB1 gene in Pakistani patients with retinoblastoma using direct sequencing analysis. Mol Vis. 2015;21:1085–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frenkel S, Zloto O, Sagi M, Fraenkel A, Pe’er J. Genotype-phenotype correlation in the presentation of retinoblastoma among 149 patients. Exp Eye Res. 2016;146:313–7. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valverde JR, Alonso J, Palacios I, Pestana A. RB1 gene mutation up-date, a meta- analysis based on 932 reported mutations available in a searchable database. BMC Genet. 2005;6:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-6-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nichols KE, Houseknecht MD, Godmilow L, Bunin G, Shields C, Meadows A, Ganguly A. Sensitive multistep clinical molecular screening of 180 unrelated individuals with retinoblastoma detects 36 novel mutations in the RB1 gene. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:566–74. doi: 10.1002/humu.20184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dimaras H, Khetan V, Halliday W, Orlic M, Prigoda N, Piovesan B, Marrano P, Corson T, Eagle RJ, Squire J, Gallie B. Loss of RB1 induces non-proliferative retinoma: increasing genomic instability correlates with progression to retinoblastoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1363–72. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klutz M, Brockmann D, Lohmann DR. A Parent-of-origin effect in two families with retinoblastoma is associated with a distinct splice mutation in the RB1 Gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:174–9. doi: 10.1086/341284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Londoño JC, Philipp SE. A reliable method for quantification of splice variants using RT-qPCR. BMC Mol Biol. 2016;17:8. doi: 10.1186/s12867-016-0060-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]