Summary

Recent experimental strategies to reduce graft‐versus‐host disease (GVHD) have focused largely on modifying innate immunity. Toll‐like receptor (TLR)‐driven myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88)‐dependent signalling pathways that initiate adaptive immune function are also critical for the pathogenesis of GVHD. This study aimed to delineate the role of host MyD88 in the development of acute GVHD following fully major histocompatibility complex‐mismatched allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT). When myeloablated BALB/c MyD88 knock‐out recipients were transplanted with C57BL/6 (B6) donor cells, they developed significantly more severe GVHD than wild‐type (WT) BALB/c hosts. The increased morbidity and mortality in MyD88–/– mice correlated with increased serum levels of lipopolysaccharide and elevated inflammatory cytokines in GVHD target organs. Additionally, MyD88 deficiency in BMT recipients led to increased donor T cell expansion and more donor CD11c+ cell intestinal infiltration with apoptotic cells but reduced proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells compared with that in WT BMT recipients. Decreased expression of tight junction mRNA in epithelial cells of MyD88–/– mice suggested that MyD88 contributes to intestinal integrity. Cox‐2 expression in the GVHD‐targeted organs of WT mice is increased upon GVHD induction, but this enhanced expression was obviously inhibited by MyD88 deficiency. The present findings demonstrate an unexpected role for host MyD88 in preventing GVHD after allogeneic BMT.

Keywords: bone marrow transplantation, dendritic cell, graft‐versus‐host disease, innate immunity, MyD88, Toll‐like receptor

Introduction

Although allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) has emerged as a curative option for many hematological malignancies, its application is limited by the frequent and often lethal complication of graft‐versus‐host disease (GVHD). The onset of GVHD usually occurs within the first few weeks after BMT and classically involves immunological damage to host organs, including the skin, liver, gastrointestinal tract and immune system by alloreactive donor T cells 1, 2. To diminish the risks of GVHD, an improved mechanistic understanding of GVHD may allow specific immune pathways in GVHD progression to be exploited therapeutically. In an attempt to reduce the severity of GVHD, several convergent lines of experimental data in recent years have demonstrated that the activating pathways of the innate immune response could be therapeutically targeted and the resulting cytokine production could be neutralized 3. Recipient conditioning prior to BMT leads to the elaboration of pathogen‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), and PAMP‐induced signaling by Toll‐like receptors (TLRs) plays a critical role in the induction of the innate immune response during BMT causing inflammation and GVHD 4. Due to the convincing evidence of the significance of TLR–PAMP interactions in the pathogenesis of GVHD, TLR signaling has become a major area in BMT research 5, 6.

Myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) is an adapter protein for TLR/interleukin (IL)‐1R signaling, with the exception of TLR‐3 production: TLR‐3 signals exclusively via the adapter molecule TIR‐domain‐containing adapter‐inducing interferon‐β (TRIF) 7. Therefore, deficiency of MyD88 should disrupt most PAMP‐induced TLR signals and potentially protect the host from GVHD‐related injury 8. However, the validity of this hypothesis has not been definitively demonstrated 8, 9, 10. Recent studies using genetically engineered mouse strains have demonstrated that the development of CD4‐ and CD8‐mediated GVHD are similar whether the host antigen‐presenting cells (APCs) are wild‐type (WT) or deficient in MyD88, TRIF or MyD88 and TRIF 9. Therefore, pathways other than those dependent on MyD88 and TRIF may also be involved in the development and progression of GVHD. In contrast, a deficiency in host MyD88 was shown to decrease GVHD by two other groups 8, 10. These studies showed a critical role of MyD88 in the exacerbation of GVHD and graft rejection. The reasons for these discrepancies in study findings are currently unclear. The timing of GVHD development may play a role, as host dendritic cells (DCs) process and present major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and peptide complexes to donor T cells early after transplantation whereas, at later time‐points, donor DCs take over this role 2.

Thus, our current understanding is that MyD88‐dependent signaling by various TLRs provides signals capable of triggering innate and adaptive immune responses, and that these responses in turn may affect the development and/or progression of GVHD. The purpose of this study was to test the role of host MyD88 in the development of acute GVHD (aGVHD) in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of mouse allogeneic transplant recipients in order to resolve the discrepancies in the results of earlier studies regarding whether MyD88 deficiency either reduces or has no effect on GVHD. Contrary to expectations, we found that MyD88‐deficient host mice exhibited a more severe GVHD phenotype than WT recipients, indicating a protective role for MyD88 in the development of GVHD after allogeneic BMT.

Materials and methods

Mice

Male C57BL/6 (B6, H‐2Kb) and female BALB/c (H‐2Kd) mice were purchased from HFK Bio‐technology Co. Ltd (Beijing, China). Female BALB/c mice engineered to lack MyD88 expression (MyD88–/–) were originally generated at the University of Chicago (Department of Medicine, Section of Rheumatology, Chicago, IL, USA) 11. All mice were 8–12 weeks old (20–24 g body weight) at the start of the experiments and housed in a pathogen‐free facility, with food and water given ad libitum. Experimental protocols were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and approved by the Tongji Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Wuhan, China).

BMT and GVHD induction

BALB/c wild‐type (WT) or MyD88–/– mice were used as transplant recipients and B6 mice as donors. Recipient mice received myeloablative total‐body irradiation (710 cGy, 200 cGy/min, X‐ray source) in two doses with a 10‐min interval between doses to minimize radio‐related toxicity. Irradiated recipients then received either 1 × 107 BM cells obtained from femurs and tibiae of donors or BMs plus spleen cells (SCs, mild GVHD, 1·0 × 107; severe GVHD, 2·0 × 107) from donor mice via tail vein injection. Prior to infusion, red blood cells containing BMs and SCs were lysed by incubation in ammonium chloride lysing solution (Beyotime) for 2 min at room temperature followed by filtration and washing with phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) to remove debris. Mice were treated with Cefaclor (100 mg/l) in their drinking water starting 1 week before transplant and continuing until 2 weeks after BMT to prevent and treat infections induced by conditioning regimens. GVHD severity was assessed using the previously described clinical scoring system 12.

Histology and confocal microscopy

Samples of small intestine and liver from recipient mice were collected and fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, cut into 5‐μm‐thick sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Immunohistochemical staining was applied to detect MyD88‐, myeloperoxidase (MPO)‐, CD11c‐ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α‐positive cells in the frozen intestine and liver sections. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI). Confocal images were obtained with a FV‐1000 Confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus). Staining of eight randomly selected areas per slide was analyzed using Image‐Pro Plus version 6.0 software.

Real‐time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and serum lipopolysaccharide (LPS) enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Total RNA was extracted from small intestine and liver tissue samples. Real‐time quantitative reverse transcription (RT)–PCR analysis was performed as previously described 13. The sequences of the PCR primers are listed in Table 1. The LPS concentration was quantified in serum samples using an ELISA kit (NeoBioscience Technology Co., Ltd, Shenzhen, China), according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol.

Table 1.

Polymerase chain reaction primers

| Gene | Primer |

|---|---|

| TNF‐α | Forward 5GAACTGGCAGAAGAGGCACT3 |

| Reverse 5AGGGTCTGGGCCATAGAACT3 | |

| IL‐4 | Forward 5GGAGATGGATGTGCCAAACG3 |

| Reverse 5TCGAAAAGCCCGAAAGAGT3 | |

| IL‐12 | Forward 5AGCTCTACAGCGAAGCACA3 |

| Reverse 5ATGCCGCAGAGGTCCAAGTT3 | |

| ZO‐1 | Forward 5ATGCCTAAAGCTGTCCCTGTG3 |

| Reverse 5GAATGGCTCCTTGTGGGATAAT3 | |

| Occludin | Forward 5CTTACAGGCAGAACTAGACGAC3 |

| Reverse 5TGATGTGCGATAATTTGCTCT3 | |

| Claudin‐3 | Forward 5ACCAACTGCGTACAAGACGAGA3 |

| Reverse 5ACCAACGGGTTATAGAAATCCCT3 | |

| β‐actin | Forward 5CTGAGAGGGAAATCGTGCGT3 |

| Reverse 5CCACAGGATTCCATACCCAAGA3 |

TNF = tumor necrosis factor; IL = interleukin; ZO = Zonula occludens.

Proliferation and apoptosis assays

In‐situ assays for cell proliferation were performed by immunoperoxidase staining for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), as detailed elsewhere, with some modification 14. The number of PCNA‐positive cells per well‐oriented crypt was calculated across three crypts for each intestinal segment at 200 × magnification by light microscopy. The results are shown as means ± standard deviations (s.d.). Apoptosis cell assays were conducted by the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) method, as described previously 15. An apoptosis index for the intestinal epithelium was calculated as the ratio of TUNEL‐positive nuclei per 100 epithelial cells counted.

Flow cytometric analysis

Host spleen cells suspended in PBS were incubated with fluorescently labeled H‐2Kb monoclonal antibodies (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) and CD4 or CD8 monoclonal antibodies (eBioscience) at 4°C for 20 min. After staining, the cells were washed twice with PBS and subjected to fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. Flow cytometric data were analyzed with Flow Jo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

Isolation of intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) and Western blotting

Primary IECs from mouse small and large intestines were isolated by modifying previously published procedures 16. All intestinal samples were dissected, slit longitudinally and washed in calcium‐ and magnesium‐free Hanks’s balanced salt solution containing 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and antibiotics (100 units/ml penicillin and 10 μg/ml streptomycin). Intestines were cut into small fragments, which were then placed in calcium‐ and magnesium‐free Hanks’s balanced salt solution containing 10% FBS, 1 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), 1 mM dithiothreitol (Sigma‐Aldrich), 100 units/ml penicillin and 10 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). The epithelial fragments were incubated at 37°C for 20 min and the supernatant was recovered after vigorous shaking on ice, then passed through a 100‐μm cell strainer and centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min. The cells were resuspended in ice‐cold PBS and counted. Extraction of proteins from intestinal epithelial cells for Western blotting was performed as previously described, with some modifications 17. Antibodies against TLR‐4, MyD88, interleukin‐1 receptor‐associated kinase 4 (IRAK‐4), phosphorylated IRAK‐4 (p‐IRAK‐4), nuclear factor kappa B (NF‐κB)p65 and Cox‐2 were purchased from Cell Signaling Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA).

Mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR)

BM‐derived DCs from WT or MyD88–/– BALB/c mice were generated as described previously 18. On day 7, the loosely adherent cells were collected, and LPS was added to the culture medium for 48 h. Flow cytometric analysis of CD40, CD80, CD86, MHCII and CCR7 expression on gated CD11c+ was conducted. Allogeneic MLR assays were performed as described, with minor modifications 19. Splenic T lymphocytes from B6 mice were labeled with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) as responders (1 × 105). BALB/c BM‐derived mature or immature DCs, as stimulators (1 × 106), were added to responders in 96‐well round‐bottomed plates and then incubated for 3 days. Proliferation of T cells was detected by fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using spss version 13.0 and Graphpad Prism version 6.0 software. Descriptive data for the major variables are shown as means ± s.d. Unpaired two‐tailed Student’s t‐tests were used to determine the statistical significance of difference in the experimental data. Survival data were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method and the log‐rank test. P‐values < 0·05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Increased MyD88 gene expression in the intestine is accompanied by GVHD progression

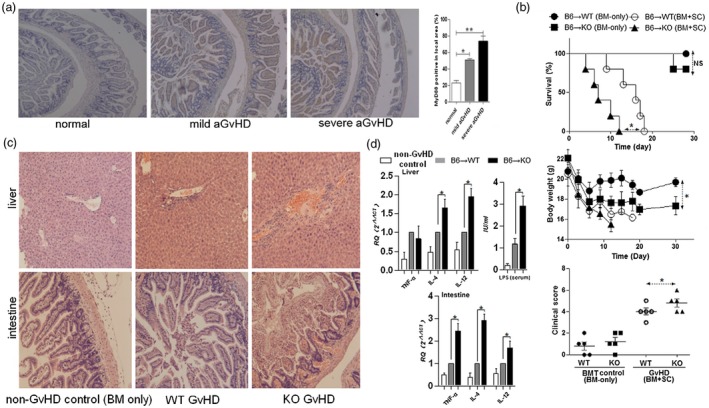

To examine the relationship between MyD88 expression and the development of aGVHD, the expression of MyD88 protein in the intestine of the mild or severe aGVHD mice was analyzed by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1a). GVHD with differing severity was successfully induced by varying the numbers of donor SCs co‐infused with BM. A classically biphasic course of murine GVHD development was observed: an initial early weight loss followed by a short recovery, which was then followed by a second phase of GVHD‐induced morbidity and mortality. This progression was dependent on the number of donor T cells injected. Pooled results revealed that MyD88 expression in intestinal epithelial cells and infiltrating inflammatory cells was significantly increased in parallel with the severity of GVHD. This indicated that MyD88 plays an important role in the development of aGVHD (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Expression of myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88) in the intestine correlates with graft‐versus‐host (GVHD) severity. BALB/c mice (WT) received total body irradiation (8·0 Gy), and then had GVHD of varying severity induced by injecting bone marrow cells (BMs, 1 × 107) along with selected numbers of spleen cells (SCs; 1 × 107 for mild GVHD; 2 × 107 for severe GVHD) from C57BL/6 (B6) mice. Healthy BALB/c mice were used as controls. At 14 days after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT), MyD88 expression in the host intestine was examined by immunohistochemical staining. Original magnification × 200. Bar = 600 μm in all panels. Semiquantitative analysis was conducted and the level of MyD88 was expressed as the percentage dyeing positive area from total area. (*P < 0·01, **P < 0·01). Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). (b) Survival, body weight and clinical score (day 7) of MyD88‐intact (WT) BMT recipients is significantly better than MyD88‐deficient (KO) recipients following induction of GVHD. For this experiment, GVHD was induced in lethally irradiated WT or KO recipients by adoptive transfer of 1 × 107 B6 BMs and 1 × 107 SCs. BMT recipients injected with B6 BMs but not SCs were used as controls (n = 5/group). (c) Representative histological sections [hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining] from the liver and intestine of mice, as in (b). Original magnification × 200. (d) At 7 days after BMT, GVHD‐related inflammatory cytokine expression in the liver and intestine and serum lipopolysaccharide (LPS) levels were quantified. Data are presented as mean ± SD of eight mice. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α, interleukin (IL)‐4 and IL‐12 expression levels are shown relative to that of β‐actin. *P < 0·05.

Increased aGVHD severity in host MyD88 mutation mice

WT and MyD88–/– BALB/c mice were transplanted with cells from B6 donors to further examine the involvement of MyD88 in the pathogenesis of aGVHD. Surprisingly, MyD88–/– BMT recipients had significantly reduced survival and developed more severe GVHD than WT recipient mice (Fig. 1b). The increased clinical signs of GVHD in MyD88–/– mice correlated with increased intestinal and hepatic damage. Samples collected from MyD88–/– mice 14 days after allogeneic BMT showed more significant histological lesions than WT host mice (Fig. 1c). These results suggest that host cell MyD88 expression protects against aGVHD.

Increased serum lipopolysaccharide (LPS) concentration and tissue GVHD‐related cytokines in MyD88–/– mice

Recent data have demonstrated that TLRs/MyD88 signaling induces GVHD‐related cytokines, such as TNF‐α, IL‐4 and IL‐12 20, 21 and PAMPs, e.g. LPS 4, are also involved in the development of GVHD. We further examined whether the increased severity of aGVHD in host mice carrying mutant MyD88 was associated with changes in the systemic levels of these factors. We examined the serum LPS concentration and TNF‐α, IL‐4 and IL‐12 expression in GVHD‐targeted tissue 7 days after BMT. Significantly higher levels of TNF‐α, IL‐4 and IL‐12 in tissue and higher concentrations of serum LPS were observed in MyD88–/–hosts compared to WT controls (Fig. 1d).

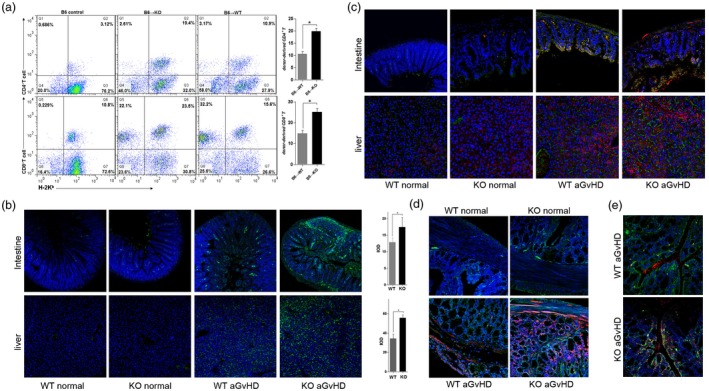

Exacerbation of GVHD in MyD88 knock‐out (KO) recipients is associated with increased numbers of donor‐derived cells

Activation of DCs, either donor‐ or host‐derived, with a TLR agonist (e.g. LPS) causes them to produce proinflammatory cytokines, which are important for initiating adaptive immunity 22. High serum LPS concentration and heavy TNF‐α mRNA expression levels in target organs after BMT may occur principally via priming the donor‐derived immune response. To test the role of donor cells in enhanced proinflammatory cytokine expression in GVHD target organs, we next compared donor‐derived cell expansion and GVHD severity in MyD88–/– or WT BMT recipients. We found that compared with WT recipients, the numbers of H‐2Kb‐positive donor cells in the spleen, small intestine and liver were greater in MyD88–/– recipients (Fig. 2a,b). To examine whether the cell types were responsible for the intestinal TNF‐α production in GVHD progression, double immunostaining for TNF‐α and donor marker H‐2Kb was conducted. The results indicated that in comparison with WT controls, the majority of TNF‐α–positive lamina propria cells were also positive for the H‐2Kb (Fig. 2c). To further substantiate the relevance of DCs in GVHD target organ damage, TNF‐α and CD11c (a DC marker) were also double‐stained in situ. Confirming previously published results 23, MyD88 deficiency in the BMT recipient was associated with more DCs that were able to induce a response to TNF‐α production (Fig. 2d). Moreover, these infiltrating DCs were also donor‐derived (Fig. 2e). Hence, these data indicate that absence of host MyD88 increases donor cell migration to target organs and could intrinsically influence DC function and cytokine production.

Figure 2.

Expansion of donor cells in the spleens of bone marrow transplantation (BMT) recipients. (a) Fourteen days after BMT, spleen cells were analyzed using two‐color flow cytometry (FlowJo version 7.6). The mean percentage [± standard deviation (s.d.)] of H‐2Kb/CD4 or H‐2Kb/CD8 double‐positive cells in one representative experiment is shown. Three independent experiments were performed, and the results were superimposable. (b) Expansion of donor cells in the intestines and livers of host mice was studied by immunofluorescent staining for donor cells on day 14 after BMT. The immunofluorescent signal [green: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)] of MHC‐I H‐2Kb was detected using a FV‐1000 confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus). Representative data from three independent experiments are reported. Magnification × 100. Quantification of the H‐2Kb expression levels was based on calculations for eight randomly selected areas per slide using Image‐Pro Plus 6.0 software. IOD = integrated optical density. *P < 0·05. (c) Double immunostaining for the donor marker H‐2Kb (green, FITC) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α [red, phycoerythrin (PE)] in the intestine. Representative data from three independent experiments are reported. Magnification × 100. (d) Double immunostaining for the dendritic cell marker CD11c (green, FITC) and TNF‐α (red, PE) in the intestine. (e) Double immunostaining for the dendritic cell marker CD11c (red, PE) and H‐2Kb (green, FITC) in the intestine. Representative data from three independent experiments are reported. Magnification × 100.

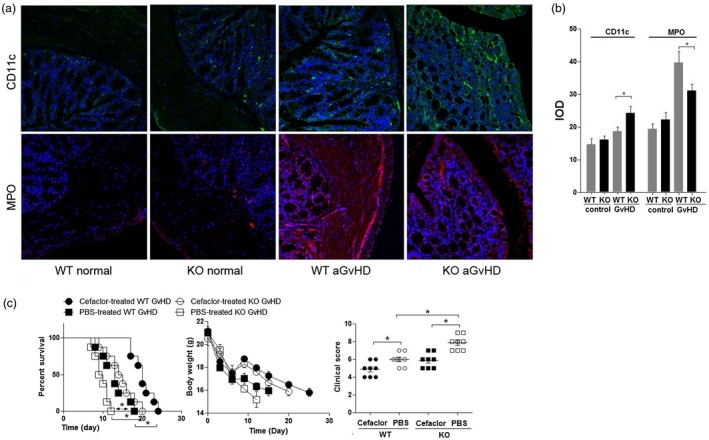

Host MyD88 deficiency is associated with increased DC but decreased neutrophil infiltration into the GVHD intestine

We next investigated how the absence of MyD88 in recipients affected the infiltration of DCs and neutrophils into the intestine 14 days after allogeneic BMT. Host MyD88 deficiency resulted in a significant increase in the number of CD11c‐positive DCs in the recipient intestine, but a decrease in myeloperoxidase (MPO)‐positive neutrophils (Fig. 3a,b). These results indicate that the increased intestinal damage observed in MyD88–/– mice was due to DCs rather than infiltrating leukocytes in the intestine, suggesting that autoimmune inflammation was dominant in GVHD progression, rather than purulent inflammation caused by enteropathogenic microorganisms.

Figure 3.

Inflammatory cell populations in the intestine of mice with acute graft‐versus‐host (GVHD). (a) Host myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88) deficiency increases CD11c+ cell [green: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)] infiltration but decreases myeloperoxidase (MPO+) neutrophil (red, PE) infiltration into the intestine. Immunofluorescent signals were detected using an FV‐1000 confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus) on day 14 after bone marrow transplantation (BMT). Magnification × 100. (b) Quantification of donor‐derived CD11c‐ and (MPO‐expressing cells. Staining of eight randomly selected areas per slide was analyzed using Image‐Pro Plus version 6.0 software. Representative data from three similar experiments are shown. IOD = integrated optical density. *P < 0·05. (c) Cefaclor therapy improves the survival, body weight and clinical score (day 10) of both MyD88 wild‐type (WT) or knock‐out (KO) BMT mice with GVHD. GVHD mortality in lethally irradiated (8·0 Gy) recipient BALB/c WT or KO BALB/c mice (n = 8/group) that received Cefaclor (100 mg/l) in their drinking water beginning 1 week before and up to 2 weeks after transplantation with 1 × 107 BMs and 1 × 107 spleen cells (SCs) from B6 donor mice. Log‐rank test *P< 0·05 for KO versus WT.

Antibiotics attenuate lethal GVHD in recipients carrying a variable MyD88 mutation

To further determine whether the increased intestinal inflammation in MyD88–/– mice was driven by unrestrained activation of innate immune pathways by microbial flora, we examined the effect of oral administration of antibiotics in both MyD88–/– and WT BMT mice with GVHD. In comparing survival between the antibiotic‐treated and PBS‐treated recipients, antibiotic therapy resulted in significantly longer survival in both groups of BMT recipients (P < 0·05, Fig. 3c).

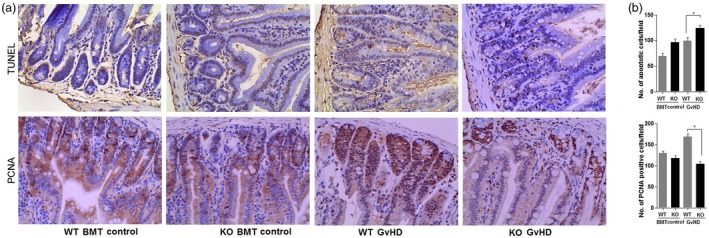

Host MyD88 deficiency is associated with apoptosis and proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells

Apoptosis is commonly used as a diagnostic marker for intestinal damage during GVHD 24. We next investigated the apoptosis and epithelial cell proliferation in BMT recipients on day 14 after GVHD induction. By staining small intestine sections for PCNA, we found that MyD88–/– recipients had significantly fewer proliferating cells than WT mice. In contrast, the numbers of TUNEL‐expressing cells were increased in the intestine of MyD88–/– mice (Fig. 4). Furthermore, we examined whether epithelial cells in MyD88–/– recipients already have a defect of proliferation/apoptosis function in steady‐state or only after BMT. Compared with normal control or BMT control mice, we found that intestinal epithelial regeneration and apoptosis in response to irradiation only were similar between WT and MyD88–/– GVHD recipients, which indicated that host MyD88 signaling is critical for reducing intestinal GVHD, and MyD88–/– mice are defective in this response.

Figure 4.

Increased apoptosis and decreased proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells in myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88)‐deficient (KO) bone marrow transplantation (BMT) mice. At 14 days after BMT, numbers of apoptotic and proliferating cells were determined in the intestine of healthy control mice and mice with graft‐versus‐host (GVHD) using Image‐Pro Plus version 6.0 software from at least six representative fields per animal [wild‐type (WT) versus knock‐out (KO)]. Apoptotic and proliferating cells were detected by staining for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), respectively (a). Magnification × 200. Data shown are from three independent experiments. (b) The numbers of TUNEL‐positive and PCNA‐positive cells were counted for each intestinal segment. Data represent means ± standard deviation (s.d.). *P < 0·05.

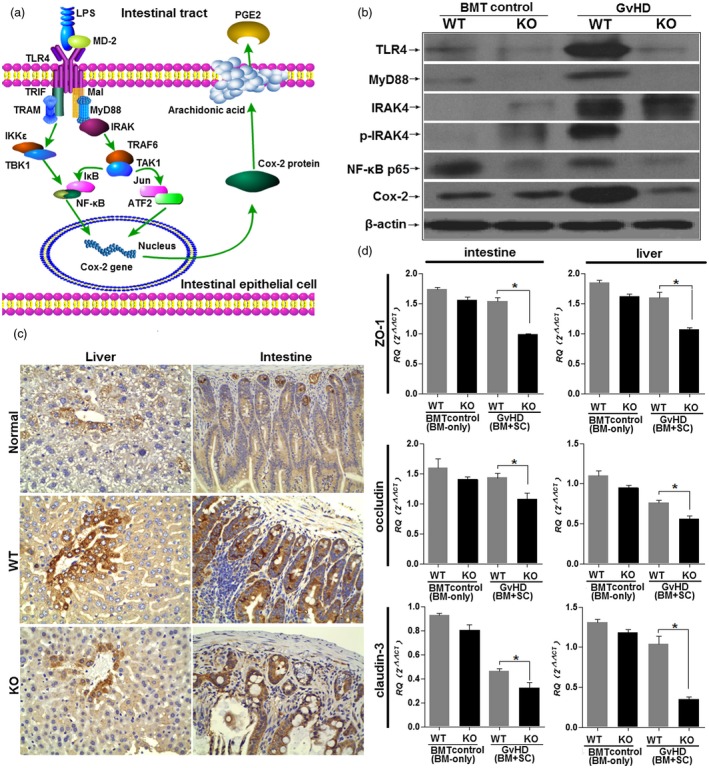

MyD88‐dependent Cox‐2 expression in epithelial cells is protective against GVHD development

Our data indicated that MyD88 signaling plays a vital role in epithelial cell proliferation in the setting of systematic GVHD. We next assessed the expression of the enzyme Cox‐2, which is frequently associated with mucosal tissue repair 15, and has been shown to be involved in a MyD88‐dependent manner in epithelial cell physiology. Interestingly, using an immunochemistry technique, we found that Cox‐2 gene expression levels were significantly increased by day 14 after GVHD induction in WT mice, and progressed to an eightfold increase in the liver and a sixfold increase in the intestine compared with expression levels in normal controls. In contrast, Cox‐2 protein expression in MyD88–/– GVHD mice was only slightly increased in these GVHD‐targeted organs (Fig. 5c). A modest increase in Cox‐2 protein expression in the mice suggested some form of compensatory response in the setting of MyD88 protection (Fig. 5a). To address how MyD88 signaling regulates Cox‐2 expression in epithelial cells, which directly influences epithelial cell proliferation and apoptosis, the expression of some key proteins of the TLR‐4/MyD88/Cox‐2 signal pathway was detected by Western blotting. Interestingly, compared with that in the WT control, the expression of all detected proteins, including TLR‐4, MyD88, IRAK‐4, p‐IRAK‐4, NF‐κBp65 and Cox‐2, significantly increased with GVHD progression. However, only IRAK‐4 expression was increased in MyD88–/– epithelial cells. Probably originating from the compensatory mechanism, this increased IRAK‐4 expression in MyD88–/– epithelial cells displayed an incompetency in the downstream expression of Cox‐2 (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88) adaptor functions in the epithelial barrier and contributes to intestinal integrity via MyD88‐dependent Cox‐2 expression. (a) Model of MyD88‐mediated epithelial cell physiology and Cox‐2 regulation. In the absence of MyD88 signaling, Cox‐2 expression is greatly decreased. (b) Inflammatory signaling pathway expression in IECs. Graft‐versus‐host (GVHD) was induced using the B6→wild type (WT) BALB/c or B6→MyD88 knock‐out (KO) BALB/c strain combination following total body irradiation. Irradiated recipients transplanted with bone marrow (BM) only served as controls. IECs were harvested on day 14 post‐bone marrow transplantation (BMT) from WT or KO recipients. Proteins were extracted and analyzed by Western blotting for Toll‐like receptor (TLR)‐4, MyD88, interleukin 1 receptor‐associated (IRAK)‐4, phosphorylated IRAK‐4 (p‐IRAK‐4), nuclear factor kappa B (NF‐κB)p65 and Cox‐2 expression. Each lane represents one experimental animal. Three animals were studied per group, and 40 μg total protein was loaded onto each lane. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments. (c) Host MyD88 deficiency decreases Cox‐2 expression in the intestine and liver of GVHD mice. At 14 days after GVHD induction, Cox‐2 expression in the intestine and liver was increased in WT recipient GVHD mice. In contrast, immunostaining for Cox‐2 was not increased in MyD88 KO GVHD mice. Magnification × 200. (d) Down‐regulation of epithelial tight junction (TJ) proteins in MyD88–/– mice. Expression of TJ proteins Zonula occludens (ZO‐1), occludin and claudin‐3 was measured by real‐time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in intestine and liver samples from WT and MyD88–/– mice at 14 days after GVHD induction. Three animals were studied in each group. *P < 0·05.

MyD88 signaling in epithelial cells maintains the intestinal and hepatic barrier

TLR signaling promotes barrier integrity and tissue repair via several anti‐apoptotic factors, such as IL‐6, which promote epithelial restitution and fortify intercellular tight junctions (TJs) that are a crucial component of the epithelial barrier 25. Next, we selected three representative TJs, Zonula occludens (ZO)‐1, claudin‐3 and occludin, to examine the function of MyD88 in the intestinal and hepatic epithelium and its role in the protection of the epithelial barrier. Comparing naive WT and MyD88–/–GVHD mice, ZO‐1, claudin‐3 and occludin showed significantly lower basal mRNA expression levels in intestine and liver samples of MyD88–/–mice (Fig. 5d)

Discussion

Increasing evidence suggests a central role for the MyD88 adaptor in the development of GVHD. TLR‐driven MyD88‐dependent immunity is critical for the rejection of MHC‐mismatched BM allografts via the induction of DC maturation, priming of donor‐reactive T cells and induction of Th1 immunity 26. In this study, we present the novel finding that host MyD88 expression is increased in the intestine in parallel with the exacerbation of GVHD, which further suggests that host MyD88 plays a role in the pathogenesis of GVHD‐induced tissue damage. However, whether increased MyD88 expression in GVHD target organs is the cause or result of GVHD progression has not been documented previously. As MyD88 signaling leads to the production of inflammatory cytokines via the activation of NF‐κB 27, we expected that host MyD88 expression would exacerbate GVHD. However, to our surprise, we found that MyD88‐deficient mice developed more severe GVHD, manifesting reduced survival, aggravated pathological lesions and increased proinflammatory cytokine expression. From these observations, we were next interested in investigating the mechanisms of exacerbated GVHD observed in MyD88‐deficient mice.

The increased level of serum LPS in MyD88–/–mice might be an important reason for GVHD development. TLR‐4/MyD88 signaling activated by LPS 28 can lead to deleterious effects such as epithelial damage via increased apoptosis and inhibited repair. In addition to MyD88 adapter, LPS‐induced signaling cascades could also be mediated by adaptor Mal in a MyD88‐independent manner 29. Probably originating from the differences in the composition of the microbiota between WT and MyD88–/–mice, there is a possible difference in the damage to the gastrointestinal tract and epithelial barrier in response to BMT conditioning. Our results are consistent with those of a previous report showing that MyD88–/– mice are insensitive to LPS‐induced death and LPS‐induced activation of both NF‐κB and mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) was delayed, rather than abolished, in these mice 30.

The observed increase in the susceptibility of MyD88–/– mice to LPS produced by enterobacteria led us to investigate how intestinal barrier function and homeostasis was impaired in these mice. As the integrity of the GI tract is dependent on the correct expression of TJ proteins, we measured the mRNA expression of occludin, ZO‐1 and claudin‐3 in intestinal and liver samples from WT and MyD88–/–mice. The reduced basal mRNA expression for these TJs in MyD88–/–mice suggested that MyD88 signaling is essential for TJ function. This conclusion was further confirmed by TUNEL and PCNA immunohistochemistry. The weakened barrier functions of MyD88–/–epithelial cells may be a major reason why MyD88–/–mice display increased epithelial damage due to reduced epithelial cell proliferation, increased apoptosis and increased LPS translocation to systematic circulation. Our data are consistent with those of previous studies obtained using the dextran sodium sulfate and Citrobacter rodentium models, which showed that MyD88 protects against intestinal inflammation, with MyD88–/– mice developing more severe colitis 31, 32.

Barrier dysfunction was next confirmed in epithelial cells, in which MyD88 expression decreased Cox‐2 expression, suggesting a basal role for MyD88 in maintaining the barrier function. It has been reported that MyD88‐dependent Cox‐2 expression in epithelial cells is essential for the tissue repair process through functions such as inducing epithelial proliferation and limiting apoptosis 15. In the setting of GVHD, we also found that Cox‐2 gene expression in WT mice was significantly elevated over the baseline level and at a level obviously greater than that in MyD88–/–mice, suggesting that GVHD‐induced expression of Cox‐2 is strictly MyD88‐dependent.

Another potential mechanism by which MyD88 deficiency accelerated GVHD pathogenesis could be the donor‐DC‐mediated classical cross‐presentation and indirect pathway, instead of a host‐DC‐mediated direct mode of antigen presentation 22. Consistent with this hypothesis, we observed that infiltration by H‐2Kb‐positive donor cells, especially donor‐derived DCs, was much greater in MyD88–/– mice than in WT mice in the spleen, the liver and the intestine. Based on these results, we hypothesize that MyD88 signaling of donor DCs is required for GVHD in the absence of host MyD88, and that these effects were mediated via TNF‐α production.

It is important to realize that, with respect to host acceptance of solid organ allografts, MyD88 deficiency promotes allograft acceptance 33, suggesting a different mechanism between GVHD and the host‐versus‐graft (HvG) response. In addition, compared with WT BMT control, BM reconstruction and body weight recovery are slow in Myd88 KO recipients (Fig. 1b). One may question why non‐GVHD control animals had difference in body weight between WT and Myd88 KO BM transplant groups. It is possible that, in the context of allo‐BMT, pathways that induce APC activation could be massively redundant, owing to the ubiquitous and abundant availability of alloantigen, such that any APC activated by any activating ligand can contribute to intestinal damage. Pathways other than those dependent on MyD88 can induce APC maturation, and we could not block all potential pathways simultaneously 9. In addition, host dysregulated TLR signaling contributes to the pathogenesis of many hematopoietic disorders, including bone marrow failure. Host TLR signaling could mediate the regulation of both normal and pathogenic hematopoiesis. Thus, for a period of time after the conditioning regimen, WT BM transplant mice could rapidly reconstitute hematopoiesis and repair radiation damage with the help of host MyD88 signaling. Both donor‐derived and recipient APCs could have played unique roles in promoting GVHD 2; even intestinal GVHD was more dependent on donor DCs 34. Host global MyD88 deficiency does not restrain DC expansion 35. These observations may also explain why MyD88 deficiency did not alleviate GVHD, as both donor‐derived APCs could also present recipient peptide antigen 2, 22. These data suggest that targeting MyD88 on both donor and recipient cells may impact GVHD responses. To this end, it would be useful to analyze double MyD88 KO mice for transplant pairs.

In conclusion, our results suggest that a MyD88‐dependent signaling pathway may inhibit GVHD injury via induction of Cox‐2 expression. The essential role for MyD88 in maintaining intestinal barrier integrity and normal epithelial cell physiology is evident. The increased expression of TJ mRNA depended on MyD88 signaling. Our data also suggest the possibility that GVHD development in the MyD88–/– mouse is dependent on the function and the proliferation of donor‐derived cells, such as CD11c+ DCs, in the GVHD target organs. These results identify a new role for host MyD88 in the protection from GVHD after allo‐BMT. From the point of view of clinical application, our data suggest that blockade of host MyD88 at the time of transplantation or before BMT is unlikely to prevent GVHD completely.

Disclosures

No financial interest/relationships relating to the topic of this manuscript have been declared. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1. PCR primers.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant #81471588) and the National Hightech Researching and Developing Program (Program 863) of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant no. 2012AA021010).

References

- 1. Anderson BE, Taylor PA, McNiff JM, et al. Effects of donor T‐cell trafficking and priming site on graft‐versus‐host disease induction by naive and memory phenotype CD4 T cells. Blood 2008;111:5242–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shlomchik WD. Graft‐versus‐host disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2007;7:340–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zeiser R, Penack O, Holler E, Idzko M. Danger signals activating innate immunity in graft‐versus‐host disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 2011;89:833–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Penack O, Holler E, van den Brink MR. Graft‐versus‐host disease: regulation by microbe‐associated molecules and innate immune receptors. Blood 2010;115:1865–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shin OS, Harris JB. Innate immunity and transplantation tolerance: the potential role of TLRs/NLRs in GVHD. Korean J Hematol 2011;46:69–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maeda Y. Pathogenesis of graft‐versus‐host disease: innate immunity amplifying acute alloimmune responses. Int J Hematol 2013;98:293–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goldstein DR. Toll like receptors and acute allograft rejection. Transpl Immunol 2006;17:11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sean Choi JM, Ju Jeon JY, Lee HY, Choi EY. The effect of MyD88 deficiency during graft‐versus‐host disease. J Undergrad Res Alberta (JURA) 2011;1:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li H, Matte‐Martone C, Tan HS, et al. Graft‐versus‐host disease is independent of innate signaling pathways triggered by pathogens in host hematopoietic cells. J Immunol 2011;186:230–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heimesaat MM, Nogai A, Bereswill S, et al. MyD88/TLR9 mediated immunopathology and gut microbiota dynamics in a novel murine model of intestinal graft‐versus‐host disease. Gut 2010;59:1079–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li C, Huang X, Liu Y, et al. Dendritic cells play an essential role in transplantation responses via myeloid differentiation factor 88 signaling. Transplant Proc 2013;45:1842–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hill GR, Cooke KR, Teshima T, et al. Interleukin‐11 promotes T cell polarization and prevents acute graft‐versus‐host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Invest 1998;102:115–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kuroiwa T, Kakishita E, Hamano T, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor ameliorates acute graft‐versus‐host disease and promotes hematopoietic function. J Clin Invest 2001;107:1365–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen Z, Wang J, Cai L, et al. Role of the stem cell‐associated intermediate filament nestin in malignant proliferation of non‐small cell lung cancer. PLOS ONE 2014;9:e85584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fukata M, Chen A, Klepper A, et al. Cox‐2 is regulated by Toll‐like receptor‐4 (TLR4) signaling: role in proliferation and apoptosis in the intestine. Gastroenterology 2006;131:862–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. DeSchoolmeester ML, Manku H, Else KJ. The innate immune responses of colonic epithelial cells to Trichuris muris are similar in mouse strains that develop a type 1 or type 2 adaptive immune response. Infect Immun 2006;74:6280–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moreira V, Teixeira C, Borges DSH, D’Imperio LM, Dos‐Santos MC. The crucial role of the MyD88 adaptor protein in the inflammatory response induced by Bothrops atrox venom. Toxicon 2013;67:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Iwamoto S, Kumamoto T, Azuma E, et al. The effect of azithromycin on the maturation and function of murine bone marrow‐derived dendritic cells. Clin Exp Immunol 2011;166:385–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Iwamoto S, Azuma E, Kumamoto T, et al. Efficacy of azithromycin in preventing lethal graft‐versus‐host disease. Clin Exp Immunol 2013;171:338–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Noori‐Daloii MR, Jalilian N, Izadi P, Sobhani M, Rabii‐Gilani Z, Yekaninejad MS. Cytokine gene polymorphism and graft‐versus‐host disease: a survey in Iranian bone marrow transplanted patients. Mol Biol Rep 2013;40:4861–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dickinson AM, Holler E. Polymorphisms of cytokine and innate immunity genes and GVHD. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2008;21:149–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paczesny S, Hanauer D, Sun Y, Reddy P. New perspectives on the biology of acute GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010;45:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaisho T, Akira S. Dendritic‐cell function in Toll‐like receptor‐ and MyD88‐knockout mice. Trends Immunol 2001;22:78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Imado T, Iwasaki T, Kitano S, et al. The protective role of host Toll‐like receptor‐4 in acute graft‐versus‐host disease. Transplantation 2010;90:1063–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Corr SC, Palsson‐McDermott EM, Grishina I, et al. MyD88 adaptor‐like (Mal) functions in the epithelial barrier and contributes to intestinal integrity via protein kinase C. Mucosal Immunol 2014;7:57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goldstein DR, Tesar BM, Akira S, Lakkis FG. Critical role of the Toll‐like receptor signal adaptor protein MyD88 in acute allograft rejection. J Clin Invest 2003;111:1571–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern‐recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll‐like receptors. Nat Immunol 2010;11:373–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hill GR, Crawford JM, Cooke KR, Brinson YS, Pan L, Ferrara JL. Total body irradiation and acute graft‐versus‐host disease: the role of gastrointestinal damage and inflammatory cytokines. Blood 1997;90:3204–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Valkov E, Stamp A, Dimaio F, et al. Crystal structure of Toll‐like receptor adaptor MAL/TIRAP reveals the molecular basis for signal transduction and disease protection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108:14879–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Unresponsiveness of MyD88‐deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity 1999;11:115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gibson DL, Ma C, Bergstrom KS, Huang JT, Man C, Vallance BA. MyD88 signalling plays a critical role in host defence by controlling pathogen burden and promoting epithelial cell homeostasis during Citrobacter rodentium‐induced colitis. Cell Microbiol 2008;10:618–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Araki A, Kanai T, Ishikura T, et al. MyD88‐deficient mice develop severe intestinal inflammation in dextran sodium sulfate colitis. J Gastroenterol 2005;40:16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Walker WE, Nasr IW, Camirand G, Tesar BM, Booth CJ, Goldstein DR. Absence of innate MyD88 signaling promotes inducible allograft acceptance. J Immunol 2006;177:5307–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Anderson BE, McNiff JM, Jain D, Blazar BR, Shlomchik WD, Shlomchik MJ. Distinct roles for donor‐ and host‐derived antigen‐presenting cells and costimulatory molecules in murine chronic graft‐versus‐host disease: requirements depend on target organ. Blood 2005;105:2227–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rivas MN, Koh YT, Chen A, et al. MyD88 is critically involved in immune tolerance breakdown at environmental interfaces of Foxp3‐deficient mice. J Clin Invest 2012;122:1933–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. PCR primers.