ABSTRACT

Toxoplasmosis, a parasitic disease in human and animals, is caused by Toxoplasma gondii. Our previous study has led to the discovery of a novel RAP domain binding protein antigen (TgRA15), an apparent in-vivo induced antigen recognised by antibodies in acutely infected individuals. This study is aimed to evaluate the humoral response and cytokine release elicited by recombinant TgRA15 protein in C57BL/6 mice, demonstrating its potential as a candidate vaccine for Toxoplasma gondii infection. In this study, the recombinant TgRA15 protein was expressed in Escherichia coli, purified and refolded into soluble form. C57BL/6 mice were immunised intradermally with the antigen and CASAC (Combined Adjuvant for Synergistic Activation of Cellular immunity). Antigen-specific humoral and cell-mediated responses were evaluated using Western blot and ELISA. The total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies specific to the antigen were significantly increased in treatment group compare to control group. A higher level of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) secretion was demonstrated in the mice group receiving booster doses of rTgRA15 protein, suggesting a potential Th1-mediated response. In conclusion, the rTgRA15 protein has the potential to generate specific antibody response and elicit cellular response, thus potentially serve as a vaccine candidate against T. gondii infection.

KEYWORDS: Toxoplasmosis, TgRA, antibody, interferon gamma, mice, vaccine, immunity

1. Introduction

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular protozoan parasite that infects warm- blooded organisms, including human and many domestic animal species [1]. Toxoplasma infection normally occurs when the resistant forms of the parasite infects undercooked meat and is ingested, subsequently affecting different parts of the human body [2]. T. gondii cysts may remain inactive in the latent state for a certain period of time and becomes reactivated when the individual’s immunity weakens, leading to serious health consequences [3].

The development of an effective vaccine is important for prevention and treatment of human toxoplasmosis. In recent years, there were only a few studies that reported vaccines against T. gondii infection in murine models [4]. Current vaccination strategies are focused on the use of parasite recombinant antigens to trigger a protective B-cell immunity and CD8+ T-cell immunity utilising appropriate immunisation approaches and delivery systems [5,6]. For example, live-attenuated vaccine was proven to be more efficient than conventional inactivated and killed vaccine, in terms of eliciting a MHC-I restricted CD8+ responses towards rapid clearance of parasite infection with protection against T. gondii [5,6]. CpG oligonucleotides and alum adjuvants were widely used as delivery system to enhance protective immune response against infection when being administrated with T. gondii antigens in the mouse model [7,8]. To effectively eradicate the pathogen, it is of utmost importance that a stronger humoral and cell-mediated immune responses are generated using vaccines that are proven to be safe [9]. Therefore, identification of a suitable target antigen is crucial to design a potent vaccine capable of eliciting protective immunity.

In a previous study, in vivo-induced antigen technology (IVIAT) was used in screening of a T. gondii cDNA library against patients’ sera, which led to the identification of a specific clone with a gene insert that expressed protein (designated as rTgRA15) reactive towards anti-Toxoplasma IgM produced during acute infection. The gene insert was expressed with RNA derived from in vivo (and not in vitro) grown T. gondii tachyzoites [10]. The gene sequence was 99% homologous to TGME49_269830; a T. gondii ME49 protein coding gene on TGME49_chrVIII from 5 586 338 to 5 589 238 (Chromosome: VIII) that encodes for the RAP domain-containing protein (GenBank accession no: 7895000). RAP domain is abundantly found in apicomplexan, and other eukaryotic proteins. It mediates a variety of cellular functions and parasite-host cell interaction, thus it is likely to be of high biological significance [11]. Studies also revealed that conserved RAP protein facilitates the survival and in vivo growth of other intracellular parasites such as Babesia bovis and Plasmodium falciparum [12,13]. Upon human infection, this antigenic protein is recognised by antibodies and ingested by the antigen-presenting cells that trigger a specific immunity against the invasion [14]. Due to these reasons, we hypothesised that TgRA15 might potentially be a candidate vaccine against T. gondii infection.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the humoral and cell-mediated immune responses elicited against rTgRA15 protein in the C57BL/6 mouse model. The mouse IgG1 and IgG2a production an important indication of the magnitude of the Th1/Th2 response [15]. Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) secretion was determined for its ability to stimulate mainly a Th1-biased T-cell response against the rTgRA15 [16]. In addition, the combined molecular adjuvant (CASAC) was used to stimulate a CD8+ T-cell mediated response, which is crucial for therapeutic purpose. This combined adjuvant regimen that contains interferon gamma and toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists triggers the activation of dendritic cells for a stronger response in cell-mediated immunity [17]. Thus, the memory and protective responses of humoral and cell-mediated immunity against rTgRA15 were investigated to assess its potential use as a candidate vaccine.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Production of rtgra15 protein in escherichia coli

The TgRA15 sequence was synthesised and cloned into pET-32 vector by Epoch Life Science (USA). The TgRA15-pET32 construct was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) expression host cells. It was first grown overnight at 37 °C in Terrific broth containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin. The following day, it was inoculated (1:100 ratio) in 500 ml broth, followed by incubation at 37 °C until it reached OD600nm of 0.5–0.6. The expression culture was induced with 1mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) with 4 h incubation at 30 °C. The histidine-tagged rTgRA15 was purified under denaturing condition using Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen USA) using the protocol suggested by the manufacturer. The final eluted protein fractions were stored in buffer containing 8 M Urea.

2.2. Refolding of the denatured rtgra15 protein

The above eluted fractions were pooled, concentrated, diluted to 6 M urea with PBS containing 0.25 M Arginine (pH 7.2), and incubated for 30 min at 4 °C. The protein was further diluted to 4 M urea, then incubated for 30 min at 4 °C. Step wise dilution was repeated to reduce the urea concentration to 3 M, 2 M and 1 M. The protein was then incubated overnight at 4 °C. The step wise dilution was again performed to further reduce the urea concentration to 0.25 M, then to 0.125 M. Finally, the protein was concentrated to 1 ml using a spin column and the concentration was determined using RCDC assay (Bio Rad, USA). To remove the undesired contaminating proteins, TgRA15 band was excised upon SDS-PAGE analysis and used for electroelution procedures. Briefly, the gel slices were loaded into Model 422 Electro-Eluter (Biorad USA) for eluted at 10 mM/glass tube constant current for 5 h. The eluted protein was collected from the remaining liquid in membrane cap. The remaining liquid (approximately 400 µl) in the membrane cap contained the eluted protein, which was then harvested for subsequent analysis. Total yield of 1.6 µg/ml rTgRA15 protein was acquired per 500 ml bacteria culture. The presence of rTgRA15 in the eluted fractions were confirmed by the detection of anti-histidine antibody in Western blot analysis as in Section 2.5.

2.3. Mass spectrometry

The purified rTgRA protein was analysed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) to confirm its identity corresponding to the correct amino acid sequence from NCBI database.

2.4. In vivo immunisation of C57BL/6 mice

Female C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from the Animal Research and Service Centre (ARASC), Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM). All mice used in this study were maintained under specific pathogen free conditions. The use of animals was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee USM (AECUSM) under USM/Animal Ethics Approval/2013/(89)(515). Mice were allowed free access to food and water throughout the study.

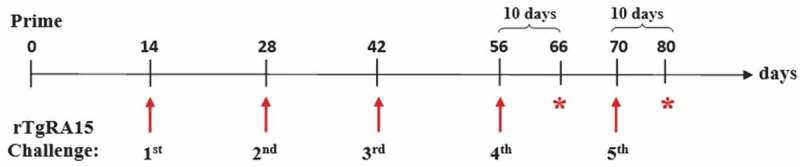

The immunisation regimen against rTgRA15 protein in C57BL/6 mouse model was established with minor modification as described [18]. Female C57BL/6 mice (n = 5) were used in each control and treatment groups. CASAC adjuvant was used in immunisation of both treatment and control groups. As shown in Figure 1, treatment mice were initially primed intraperitoneally with 400 µg of rTgRA15 antigen, while the control group was injected with sterile PBS and CASAC. At day 14, the treatment group received intradermal injection of 200 µg of rTgRA15 antigen at 2-weeks interval. The mice were immunised five times at days 14, 28, 42, 56 and 70. Ten days after the 4th and 5th immunisation, mouse sera and peripheral mononuclear cells (PBMC) were harvested at day 66 and 80, respectively. The collected mouse sera and PBMC were used for analysis of IgG antibody response and IFN-γ production, respectively. The entire immunisation experiment was repeated three times to ensure the reproducibility of the generated data (n = 3 for 1st and 2nd experiment; n = 5 for 3rd experiment).

Figure 1.

Immunisation regimen for rTgRA15 protein in C57BL/6 mouse model. A total of five mice (n = 5) were used in each control and treatment groups, which were injected with PBS+ CASAC and rTgRA15+ CASAC, respectively. The treatment mice were initially primed with 400 µg protein, followed by five booster doses with 200 µg protein in 2-weeks interval at day 14, 28, 42, 56 and 70. At day 66 and 80, each mouse sera and PBMC was harvested for respective evaluation of IgG antibody response and IFN-γ secretion.

2.5. Western blot analysis

The 6xHistidine-tagged TgRA protein was analysed by Western blot using anti-histidine antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Biolegend USA). Briefly, rTgRA15 protein was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (NCP). The blot was washed three times with TBS-T (10 mM Tris–HCl; pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20). NCP was blocked with 3% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) for 2 h at 4 °C. After washing, the membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-histidine antibody at 1:1000 dilution for 1 h. Following washing steps for 3 times, the membrane was developed with 4CN-3,3ʹ-diaminobenzidine (CN/DAB) substrate after incubation for 5 to 10 min (Nacalai, Japan).

2.6. Igg ELISA

The 96-well flat bottom ELISA plate was coated with rTgRA15 protein (5 μg/ml, 50 µl) in coating buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3, pH 8.3) and Igκ light chain for standard (2 µg/ml, 50 µl) in triplicates. The plate was then incubated overnight at 4 °C. After washing the plate three times with 200 µl PBST, each well was blocked with 200 μl/well of 1% BSA in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. The plate was washed three times with wash buffer PBST. For wells coated with rTgRA15 protein, the mouse sera (50 μl/well) were added in 1:100 dilutions and incubated at 4°C for overnight. For positive control, the IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a standard antibody were added (1 µg/ml, 50 µl) in wells coated with Igκ light chain (10 µg/ml) in triplicates, respectively. The PBS was used to replace serum in negative control wells. After washing with PBST for three times, the biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG1 or IgG2a conjugated (1:2000) was added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, a total of 50 μl/well Streptavidin-HRP (1:10,000) was added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The plate was washed six times with PBST, followed by development in 100 μl ABTS substrate with 0.01% H2O2. The absorbance at OD405nm was measured after 30 min using the MultiskanTM Microplate Photometer (Thermoscientific). Results were determined by subtracting the background values from sample values at 405 nm. Positive and negative controls were included in each running of the experiment.

2.7. In vitro stimulation of mouse PBMC

Mouse peripheral mononuclear cells (PBMC) were initially prepared by lysing a total of 200 µl mouse whole blood with 1 ml RBC lysis solution. After incubation at 4 °C for 10 min, it is centrifuged at 300 xg for 5 min and the supernatant was discarded to remove the residual debris. The samples were washed with 1 ml 1 x PBS until the RBC is totally removed. RPMI media (20 ng/ml IL-2, 1 % Pen-Strep and 10 % FBS) was added into each sample at cell number of 1 × 106 cells/ml. A total of 200 µl of sample was added into each well of round bottom culture plate. To stimulate the antigen-specific response, a total of 20 µg rTgRA15 protein was added into each sample of control and treatment group. The sample wells without addition of rTgRA15 protein are the negative control; while Concanavalin A (1 µg/ml) was added as the positive control of the assay.

2.8. Interferon gamma (ifn-γ) ELISA

The 96-well ELISA plates were coated with anti-mouse IFN-γ antibodies (clone: R4-6A2; 1 μg/ml) (coating buffer is 0.1 M NaHCO3, pH 8.3). After incubation at 4°C overnight, the plates were washed three times with TBS-T and followed by blocking with 1% BSA in TBS-T at room temperature for overnight. After washing three times with TBS-T, the culture supernatants from the stimulated samples were diluted in 1:1 ratio with 100 µl RPMI media and added into each well. For positive control, culture supernatant stimulated by concanavalin A was added into each triplicate well. Concanavalin A was chosen as the positive control for its ability to stimulate PBMC proliferation and IFN-γ secretion in murine T-cells. Recombinant mouse IFN-γ ELISA standards (Biolegend, USA) was used to generate the standard curve comprising of two-fold dilutions at concentration ranging from 2000 to 15 pg/ml. The RPMI media was used to replace the culture supernatant in negative control wells. The plates were incubated at 4°C overnight and then washed three times with TBS-T. The samples in each well were incubated with biotinylated anti-mouse IFN-γ (clone: XMG1.2, Biolegend) at final concentration of 1 µg/ml. After washing the plate for six times with PBST, a total of 100μl ABTS substrate was added into each well and incubated for 15 min. The absorbance was measured using the MultiskanTM Microplate Photometer (Thermoscientific). The results were expressed in concentration (pg/ml) versus study groups.

2.9. Statistical analysis

The experimental data was expressed as mean ± standard error mean (SEM) using one-way ANOVA and student t-test, where value p ≤ 0.05 is considered significant. All graphs and statistical calculations were analysed using GraphPad Prism software.

3.0. Results

3.1. Detection of anti-histidine rtgra protein in refolded fractions

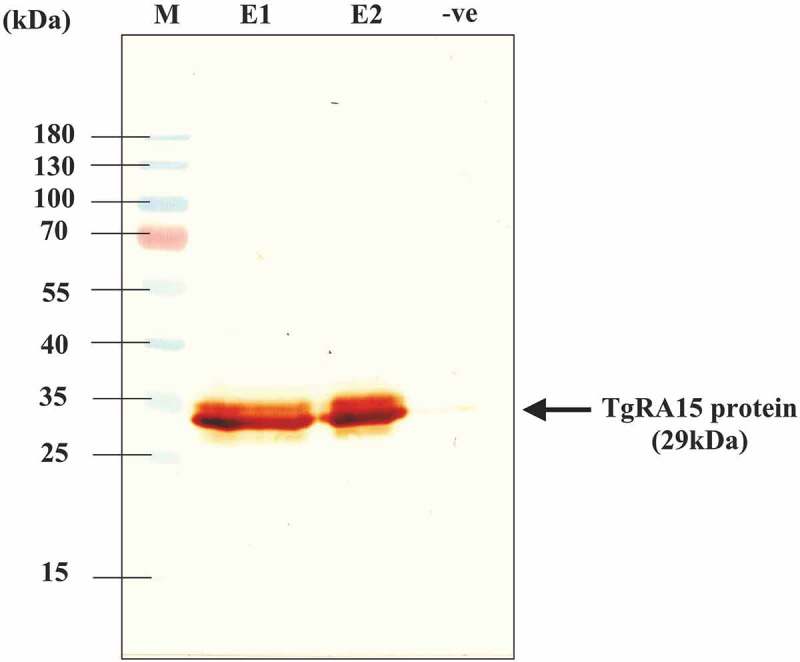

In Western blot analysis, a 2–4 µg/well of refolded TgRA15 protein was blotted on a NCP and incubated with anti-histidine antibody conjugated with HRP. An intense band at 29 kDa with strong detection was observed in the first and second fractions (lane E1 and E2) following electroelution steps, as shown in Figure 2. No bands were observed in negative control containing non-histidine tagged protein.

Figure 2.

Detection of histidine-tagged TgRA15 protein in Western blot analysis. An intense band was observed at 29 kDa in E1 (4.5 µg) and E2 (2 µg) fraction eluted from electrophoresis. No significant band was observed in the negative control containing protein without having histidine fusion tag. M indicated the PageRulerTM prestained protein ladder as reference. An intense band was observed at ~ 29 kDa as shown by the black arrow.

3.2. Production of rtgra15-specific igg, igg1 and igg2a antibody detected by indirect ELISA

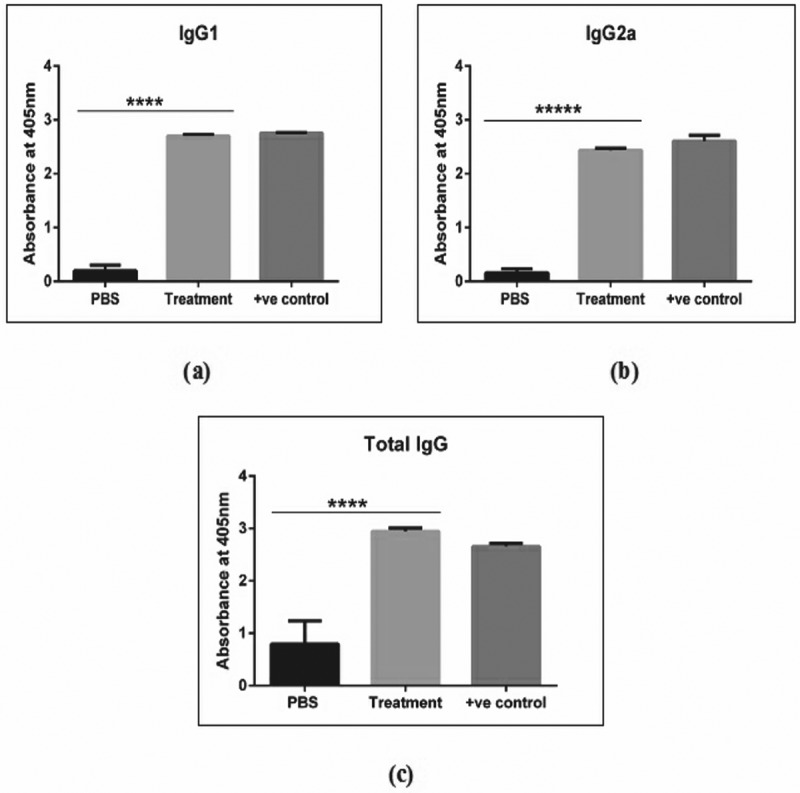

To investigate the persistence of humoral response, the C57BL/6 mice in the control and treatment group were immunised with PBS and rTgRA15 antigen respectively in five booster dose. Upon final boost at day 66 and 80, the collected mouse sera were used for detection of total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a antibody response against rTgRA15 antigen using indirect ELISA.

The levels of antigen specific total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies in the immunised mouse sera were measured using indirect ELISA as reported by [18]. As shown in Figure 3, the treatment group immunised with rTgRA15 antigen showed a significantly greater absorbance value (405 nm) of total IgG antibody production compare to control group. Similarly, higher levels of IgG1 and IgG2a responses were detected in the treatment group, suggesting a substantial stimulation of Th1 and Th2 response specific to the rTgRA15 antigen, respectively. In comparison, the total IgG antibody has a higher level than IgG1 and IgG2a subtype antibody (p < 0.0001). However, levels of antigen-specific IgG1 and IgG2a were not significantly different in the treatment group. The detection of all types of IgG antibodies was comparable to the respective monoclonal IgG antibody (1 µg/ml) that was used as the positive control. The IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a antibody responses were similar upon 4th and 5th boosting vaccination (results not shown).

Figure 3.

The antigen-specific IgG antibody response in C57BL/6 mouse model. The rTgRA15 treatment group has shown a significant higher production of IgG1 (a), IgG2a (b) and total IgG (c) antibody level as compared to PBS control group. The respective IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a monoclonal antibody was used as the positive control in the sandwich ELISA analysis. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and significance level is determined at ****p < 0.0001 (n = 5).

3.3. Interferon gamma (ifn-γ) secretion upon rtgra15 stimulation

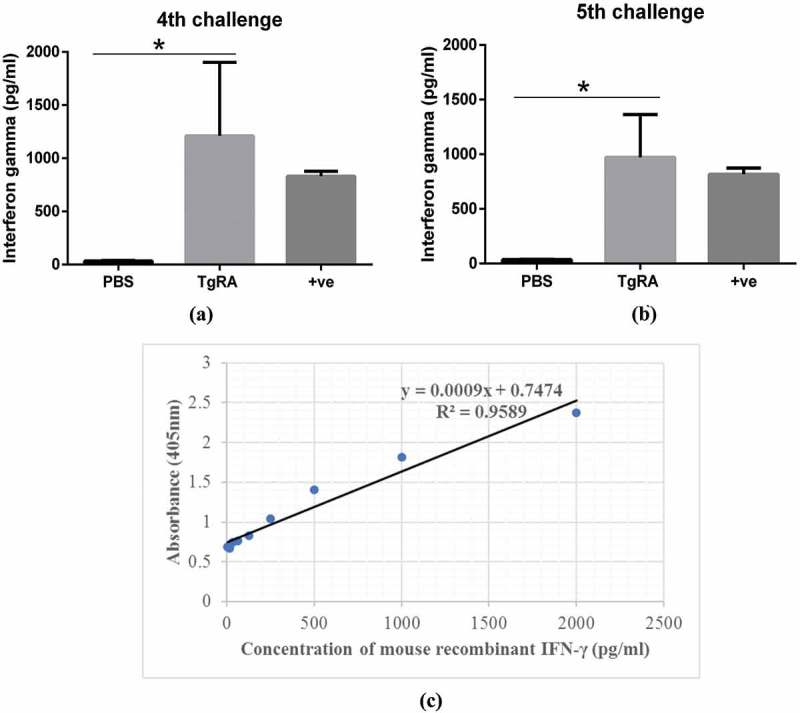

To evaluate the Th1-mediated response generated upon antigen immunisation, the production of IFN-γ in control and treatment group was assessed upon in vitro stimulation of PBMC with IL-2 and rTgRA antigen. PBMC contains cellular components from the systemic circulation, which could represent the effector functions of differentiated T-cells. Ten days after 4th and 5th boost, supernatants from the culture of stimulated mouse PBMC were analysed for IFN-γ detection in sandwich ELISA. As shown in Figure 4, the level of antigen-specific IFN-γ production in treatment group was significantly higher than PBS at two different time points. No significant difference was observed on the release of IFN-γ between 4th and 5th immunisation but with good persistence at absorbance between 1 to 1.5. The level of IFN-γ generated in the treatment group stimulated with TgRA and Concanavalin A (positive control for IFN-γ stimulation) are similar, concluding that Th1-specific responses were generated.

Figure 4.

Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) secretion against rTgRA15 antigen. The treatment group had significantly higher level of IFN-γ production than PBS control group upon 4th (a) and 5th (b) boost of rTgRA15 antigen, respectively. Concanavalin A (1 µg/ml) was used as the positive control, showing no significance difference compare to rTgRA15 treatment group. Level of mouse IFN-γ in each sample was determined from the standard curve (c) of absorbance (405nm) versus concentration of serially-diluted recombinant interferon-gamma (pg/ml). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and significance level is determined at *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 (n = 5).

4. Discussion

T. gondii oocyts shed from the faeces of an infected cat contaminate the environment, and the sporulated form are transmissible to the intermediate host, including human. Another mode of infection is by ingestion of undercooked meat containing cysts. The oocyts and cysts transform into tachyzoites, then into bradyzoites, which can remain in the host tissue for life [19]. In addition, congenital infection can occur through vertical transmission from an acutely infected mother to her foetus.

In the present study, rTgRA15 protein was investigated as a candidate vaccine against T. gondii infection. This is due to the previous findings that the RNA expression of the gene encoding this protein seemed to occur only in T. gondii tachyzoites grown in vivo and not expressed by RNA from in vitro grown tachyzoites [10,20]. Such in vivo induced proteins are deemed as potential virulence determinant and may contribute to the pathogenicity of an organism and potentially serve as an infection marker or a vaccine candidate [21]. Furthermore, the corresponding recombinant protein was also found to be antigenic [10]. We hypothesised that immunity elicited against rTgRA15 protein might help to hinder the tachyzoites and bradyzoites development in the host tissue, which will be useful for prophylactic vaccine development against T. gondii infection. Thus, this study was conducted to investigate the potential of rTgRA15 as a candidate vaccine. The CASAC adjuvant used in this study was to promote an improved CD8+ T-cell immune response against the target antigen. Mice immunisation regimen of using 400 µg priming dose and 200 µg intradermal injection dose has consistently shown upregulation of humoral and cellular immunity against target antigen, as previously reported in Wells et al. 2008 [17] and McHeyzer-Williams et al. 2015 [22]. The antigen was intradermally injected to enhance the co-stimulation mechanism between the antigen and phagocytic cells followed by subsequent activation for effector functions [23]. The immunogenicity of rTgRA15 was further evaluated in C57BL/6 mouse model to validate its potential use as a future vaccine against toxoplasma infections. The in vivo immunisation strategy involved priming and boosting immunisation of the animal with the rTgRA15 antigen and CASAC adjuvant. The priming of the mouse in high amount of rTgRA15 antigen (400 µg) was necessary to initiate the activation of naïve immune cells to its desired effector functions [24]. The consecutive immunisations exposed the immune system with the same antigen in a consistent manner. The repeated immunisation triggered immunological responses against the antigen which increased the generation of substantial amount of memory immune cells, including B- and T-cells [25].

During initial course of parasitic infection, IgG antibody is produced in the high abundance to provide humoral protection in the infected host. Our study demonstrated generation of humoral IgG immune response against rTgRA15 antigen in the experimental mouse model. Total IgG represents different antibody subtypes, including IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b and IgG4 antibodies, that can be detected by using Ig ELISA. The detection of total IgG represents all antibody subtypes, including IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b and IgG4 antibodies. These antibody subtypes are responsible during the course of an infection, such as neutralisation, opsonisation and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) response mediated by macrophages and dendritic cells. These mechanisms will help in the prevention of the parasitic infection [26].

In cell-mediated immunity, the naïve CD4+ T-cell can be differentiated into T-helper type 1 (Th1) and type 2 (Th2) to enhance the protective immune response [27]. The production of specific IgG1 and IgG2a subclass defines the polarity of the T-cell response upon antigen immunisation [28]. The increased level of IgG1 and IgG2a was observed in the mice group treated with rTgRA15 antigen compare to the group injected with PBS, suggesting the initiation of Th1 and Th2 activity. IgG1 antibody is the most abundant IgG subtypes that represents the Th2 response that activates the B cells into plasma cells, producing antigen-specific antibody against the foreign antigen [29]. The IgG2a antibody is secreted with the rise of Th1 cells, thereby it may reflect a propensity to promote a cytotoxic activity against infected cells [30]. In addition, persistent IgG antibody production after post-vaccination suggested an enhanced immunological memory to elicit a stronger response upon secondary exposure [31]. The levels of IgG2a and IgG1 were rather similar, without causing Th1/Th2 predominance upon the booster vaccination.

Stimulation of CD8+ cytotoxicity T lymphocyte is the hallmark of vaccine-induced immunity to protect the healthy cells from being infected by the pathogens [32]. Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) is one of the most important markers to elucidate the stimulation of Th1-mediated CD4+ or CD8+ T-lymphocyte reaction [33]. In the animal mouse model in this study, repeated vaccination had shown a significant increase in production of IFN-γ in the mice immunised with the rTgRA15 antigen. The secretion of IFN-γ from the immune cells promotes the proliferation and activation of CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell activity that might contribute to the direct killing of the infected cells [27].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the rTgRA15 antigen in combination with the CASAC adjuvant yield significant humoral and cell-mediated immunity responses. Elicited humoral and cell-mediated immunity exhibited a persistent memory response indicating TgRA15 protein as a potential candidate vaccine. Future investigations with challenge experiments are now required to understand its detailed protective mechanism involved in the use of rTgRA15 to prevent Toxoplasma gondii infection.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Bridging Grant, USM (304/CIPPM/6316225), Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS, 203/CIPPM/6711380) and the Higher Institution Centre of Excellence grant (HICoE, 311/CIPPM/4401005) provided by the Ministry of Education(MOE), Malaysia.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the technical contributions from Siti Naquiyah Tan Farrizam, Chang Chiat Han and Muhammad Hafiznur Yunus.

Author’s contributions

Lew MH conducted the in vivo experiment and measurement of the protective immune responses in mice. Lew MH and Tye GJ contributed to planning, data analysis and manuscript writing. RN supervised and planned rTgRA15 production and Western blot as well as edited the manuscript. MMAK developed the method to renature the recombinant protein. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

RN is the principal inventor in a pending patent by Universiti Sains Malaysia, entitled ‘In vivo-induced Toxoplasma gondii Protein for Application in Diagnosis, Vaccine and Therapy’ which has been filed in Malaysia (PI2014002940) and PCT (PCT/IB2015/057522) (1/10/2015)

References

- [1].Torgerson PR, Mastroiacovo P.. The global burden of congenital toxoplasmosis: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2013July1;91(7):501–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Blader IJ, Coleman BI, Chen CT, et al. Lytic cycle of Toxoplasma gondii: 15 Years Later. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2015;69:463–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Flegr J, Prandota J, Sovičková M, et al. Toxoplasmosis – A global threat. Correlation of latent toxoplasmosis with specific disease burden in a set of 88 countries. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jongert E, Roberts CW, Gargano N, et al. Vaccines against Toxoplasma gondii: challenges and opportunities. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009March;104(2):252–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Liu Q, Singla LD, Zhou H. Vaccines against Toxoplasma gondii: status, challenges and future directions. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8(9):1305–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Verma R, Khanna P. Development of Toxoplasma gondii vaccine: A global challenge. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(2): 291–293. 10/3009/26/received10/07/accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].El-Malky M, Shaohong L, Kumagai T, et al. Protective effect of vaccination with Toxoplasma lysate antigen and CpG as an adjuvant against Toxoplasma gondii in susceptible C57BL/6 mice. Microbiol Immunol. 2005;49(7):639–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Song P, He S, Zhou A, et al. Vaccination with toxofilin DNA in combination with an alum-monophosphoryl lipid A mixed adjuvant induces significant protective immunity against Toxoplasma gondii. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:19, 01/0508/23/received12/21/accepted [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dupont CD, Christian DA, Hunter CA. Immune response and immunopathology during toxoplasmosis(). Semin Immunopathol. 2012September7;34(6):793–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Noordin RB, Amerizadeh A, Inventorin-vivo induced Toxoplasma gondi protein for application in diagnosis, vaccine and therapy. 2016.

- [11].Lee I, Hong W. RAP–a putative RNA-binding domain. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004November;29(11):567–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Brown WC, McElwain TF, Hotzel I, et al. Helper T-cell epitopes encoded by the Babesia bigemina rap-1 gene family in the constant and variant domains are conserved among parasite strains. Infect Immun. 1998April;66(4):1561–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ghosh S, Kennedy K, Sanders P, et al. The Plasmodium rhoptry associated protein complex is important for parasitophorous vacuole membrane structure and intraerythrocytic parasite growth. Cell Microbiol. 2017 Aug;19(8). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Norimine J, Mosqueda J, Suarez C, et al. Stimulation of T-helper cell gamma interferon and immunoglobulin G responses specific for Babesia bovis rhoptry-associated protein 1 (RAP-1) or a RAP-1 protein lacking the carboxy-terminal repeat region is insufficient to provide protective immunity against virulent B. bovis challenge. Infect Immun. 2003September;71(9):5021–5032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rostamian M, Sohrabi S, Kavosifard H, et al. Lower levels of IgG1 in comparison with IgG2a are associated with protective immunity against Leishmania tropica infection in BALB/c mice. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2015May14;50(2):160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sturge CR, Yarovinsky F. Complex immune cell interplay in the gamma interferon response during Toxoplasma gondii infection. Infect Immun. 2014August;82(8):3090–3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wells JW, Cowled CJ, Farzaneh F, et al. Combined triggering of dendritic cell receptors results in synergistic activation and potent cytotoxic immunity. J Immunol. 2008September01;181(5):3422–3431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lew MH, Lim RL. Expression of a codon-optimised recombinant Ara h 2.02 peanut allergen in Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016January;100(2):661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dubey JP, Lindsay DS, Speer CA. Structures of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites, bradyzoites, and sporozoites and biology and development of tissue cysts. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998April;11(2):267–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Amerizadeh A, Muhammad HY, Khoo BY, et al. Toxoplasma gondi cDNA clone encoding RNA-associated protein (RAP) domain-containing protein is expressed by in-vivo and not by in-vitro grown tachyzoites unpublished data. 2017.

- [21].Handfield M, Brady LJ, Progulske-Fox A, et al. IVIAT: a novel method to identify microbial genes expressed specifically during human infections. Trends Microbiol. 2000July;8(7):336–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Milpied PJ, Okitsu SL, et al. Class-switched memory B cells remodel BCRs within secondary germinal centers. Nat Immunol. 2015March;16(3):296–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Tye GJ, Ioannou K, Amofah E, et al. The combined molecular adjuvant CASAC enhances the CD8+ T cell response to a tumor-associated self-antigen in aged, immunosenescent mice. Immun Ageing. 2015;12:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Woodland DL. Jump-starting the immune system: prime-boosting comes of age. Trends Immunol. 2004February;25(2):98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Castellino F, Galli G, Del Giudice G, et al. Generating memory with vaccination. Eur J Immunol. 2009August;39(8):2100–2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lux A, Yu X, Scanlan CN, et al. Impact of immune complex size and glycosylation on IgG binding to human FcgammaRs. J Immunol. 2013April15;190(8):4315–4323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Schroder K, Hertzog PJ, Ravasi T, et al. Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J Leukoc Biol. 2004February;75(2):163–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Irani V, Guy AJ, Andrew D, et al. Molecular properties of human IgG subclasses and their implications for designing therapeutic monoclonal antibodies against infectious diseases. Mol Immunol. 2015October;67(2 Pt A):171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Vidarsson G, Dekkers G, Rispens T. IgG Subclasses and Allotypes: from Structure to Effector Functions. Front Immunol. 2014;5: 520 10/2008/31/received10/06/accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bruhns P. Properties of mouse and human IgG receptors and their contribution to disease models. Blood. 2012June14;119(24):5640–5649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mueller SN. Grand Challenges in Immunological Memory [Specialty Grand Challenge]. Front Immunol. 2017April05;8(385). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hamilton SE, Jameson SC. CD8 T cell quiescence revisited. Trends Immunol. 2012February21;33(5):224–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Schoenborn JR, Wilson CB. Regulation of interferon-gamma during innate and adaptive immune responses. Adv Immunol. 2007;96:41–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]