Short abstract

Objective

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, and radiofrequency catheter ablation of AF (RCAAF) has become increasingly popular. Cardiac stress and inflammation have been associated with AF. This study was performed to determine whether the pre- or post-AF ablation levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) are predictive of AF recurrence.

Methods

This multicenter prospective cohort study involved patients undergoing RCAAF in Switzerland and Canada. The primary endpoint was the recurrence of AF or atrial flutter at 6 months.

Results

Of 202 patients, 195 completed follow-up (age, 57.5 ± 9 years; mean left ventricular ejection fraction, 62%; mean left atrial size, 19.4 cm2). Patients with AF recurrence had larger atrial surfaces and longer total RCAAF times. Both the pre-ablation hs-CRP level and 1-day post-RCAAF NT-proBNP level were significantly associated with an increased risk of recurrence.

Conclusions

The pre-ablation hs-CRP level and immediate post-ablation NT-proBNP level were markers for atrial arrhythmia recurrence after RCAAF. This confirms growing evidence of the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of AF. These biomarkers appear to be promising stratification tools for selection and management of patients undergoing RCAAF.

Keywords: Catheter ablation, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, natriuretic peptides, C-reactive protein, recurrence

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia and has a major impact on morbidity and mortality.1,2 The prevalence of AF increases with age3; the reported prevalence is 0.5% among individuals aged 50 to 59 years and up to 8.8% among individuals aged 80 to 89 years.4 The AF-associated morbidity rate is high, and the mortality rate is nearly twice that of individuals with sinus rhythm; mortality is mainly due to cerebral stroke.4 Medical treatment of AF has yielded only partial success5–9 and is often associated with numerous adverse effects. The clinical use of radiofrequency catheter ablation of AF (RCAAF), mainly with pulmonary vein isolation, has greatly increased over the past several years10 despite a significant recurrence rate and the fact that the success rate remains at approximately 70% after the first intervention and 80% after two or more interventions.

AF is a disorganized tachyarrhythmia with irregular atrial activity initiated by ectopic foci from around or inside the pulmonary veins. Atrial flutter, an organized tachyarrhythmia caused by a macro-reentry circuit in the right atrium,11 often coexists with AF. RCAAF essentially involves ablation of lesions to electrically isolate the pulmonary veins and additional lesions, thus suppressing the arrhythmogenic substrate in the atria. This intervention requires a trans-septal approach and may be complicated by periprocedural hematomas, perforations, tamponade, stroke, and pulmonary vein stenoses.12–15 Therefore, identification of novel markers that will enable better selection of patients who could benefit from RCAAF is important. Current risk factors (such as an enlarged left atrium, prolonged duration of AF, and presence of structural heart disease) are less helpful predictors of AF recurrence after electrical or pharmacologic cardioversion because these parameters have been shown to lack proper accuracy16 and are variably present in patients eligible for RCAAF. In contrast, inflammation and neurohumoral activation have been shown to play a role in the pathogenesis of AF and in the recurrence of AF following RCAAF.17–22 Two biomarkers reflecting and modulating these processes, namely N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP)23 and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP),24 have been shown to predict AF recurrence unrelated to RCCAF.22–24 Interestingly, in a recent large population-based study including 5000 patients, these biomarkers provided incremental prognostic accuracy over clinical predictors, improving the net reclassification of patients by more than 13%.25 Nevertheless, whether these two biomarkers are useful predictors of AF recurrence after RCAAF remains unclear.

This study was performed to assess whether the pre- and/or post-ablation plasma levels of hs-CRP and NT-proBNP are predictive of recurrence of AF and/or atrial flutter in this population.

Methods

Study population

This multicenter prospective cohort study included all eligible patients undergoing RCAAF at the Geneva University Hospital, Switzerland and Montreal Heart Institute, Canada during a 20-month period. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of both centers, and all patients provided written informed consent before inclusion. The inclusion criteria were an age of >18 years, documented paroxysmal or persistent AF for <2 years (thus including long-standing persistent AF) with or without typical atrial flutter [documented by electrocardiography (ECG) or Holter monitoring] after failed treatment with at least one class I or III anti-arrhythmic agent, and a clinical indication for RCAAF. The exclusion criteria were the presence of a reversible cause of AF, New York Heart Association class IV heart failure, a left atrial anteroposterior diameter of >55 mm measured by transthoracic echocardiography on a parasternal long-axis view, a left ventricular ejection fraction of <30%, any severe cardiac valve disease, and a history of prior AF ablation.

The following information was collected on standardized case report forms: baseline demographics, history and physical examination findings, cardiovascular risk factors, RCAAF parameters (including total ablation time), procedural complications, 12-lead ECG at 24 hours and 1 and 6 months after RCAAF, Holter monitoring immediately after and 6 months after RCCAF, echocardiographic findings at baseline (left ventricular ejection fraction, left atrial dimensions, and estimation of pulmonary hypertension), and 6-month clinical follow-up data. Recurrence was defined as documented AF or flutter lasting >30 seconds.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the recurrence of AF or typical/atypical atrial flutter documented by ECG or Holter monitoring. The secondary endpoints were the plasma level of NT-proBNP at 24 hours and the NT-proBNP and hs-CRP levels at 6 months after RCAAF.

RCAAF

During the first RCAAF procedure, pulmonary vein isolation was performed in all patients. One or multiple linear ablation lesions were added at the operator’s discretion depending on the characteristics of the arrhythmias induced during the procedure. Cavotricuspid isthmus ablation was also carried out in selected patients with clinical documentation of typical atrial flutter. A second RCAAF was permitted in case of recurrence within the first 3 months following the initial procedure with the same protocol as the index intervention. Specifically, recurrence of AF or typical/atypical atrial flutter was defined as recurrence after the first procedure only, and events were censored at this point; therefore, a second recurrence was not accounted for. The operators were not aware of the baseline NT-proBNP and hs-CRP levels at the time of the procedure.

Biochemical analyses

Blood samples were taken the day preceding the RCAAF intervention, the day following the intervention, and at 6 months after RCAAF. Plasma samples obtained from blood centrifugation were maintained at −70°C until testing. Both the NT-proBNP and hs-CRP levels were dosed at the central laboratory of the Montreal Heart Institute on a routine autoanalyzer (Elecsys™; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) using electrochemiluminescence and immunonephelometric methods. The NT-proBNP level was measured at baseline, day 1 post-ablation and at the 6-month follow-up, and the hs-CRP level was measured at baseline and at the 6-month follow-up.

Echocardiography

Echocardiograms were obtained and analyzed according to a standardized protocol in a core laboratory by two cardiologists blinded to the clinical and biomarker data.

Statistical analysis

Clinical data, biomarkers, and echocardiographic data are presented using descriptive statistics with mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range for continuous variables and number and percentage for categorical variables.

Univariate analysis was used to identify potential predictive characteristics of AF recurrence using the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test or Fisher’s exact test based on the continuous or categorical nature and normal or non-normal distribution of the variables. For the primary endpoint and for each biomarker, we conducted a Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Cox proportional hazard regression risk analysis was performed with AF recurrence at 6 months as the dependent variable and measurement of the biomarker levels at baseline in continuous form as the independent variable. Cox analysis was also performed for AF recurrence at 3 to 6 months and for patients with an hs-CRP level of <10 mg/L (upper limit of the reference range). Significant variables (including procedural variables), as well as age and sex based on epidemiological considerations, were then included in multivariate logistic regression models using a stepwise selection process to adjust for confounding factors. Statistical significance was determined at a P-value of 0.05. To account for correlations between repeated measures in a given individual and to integrate baseline biomarker levels, adjusted Cox regression models were carried out with inclusion of an interaction term for the baseline NT-proBNP and hs-CRP values. All analyses were conducted with STATA 11.1 and R Statistics 3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

In total, 202 patients were recruited: 147 at the Geneva University Hospital and 55 at the Montreal Heart Institute. Baseline data were incomplete for 5 patients, leaving 197 patients available for analysis. Furthermore, recurrence data were not obtained at 6 months for two patients. The baseline demographic and medical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference in demographics between patients with and without recurrence. The mean age of all patients was 57.5 ± 9.2 years, the mean body mass index was 30 kg/m2, and 82% were men. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 62%, and the mean left atrial size was 19.4 cm2. The hs-CRP and NT-proBNP levels at admission were similar in both groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

| Total | Recurrence at 6 mos | No recurrence at 6 mos | P-value (recurrence vs. no recurrence of AF) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n = 197 | n = 101 (51.3%) | n = 94 (47.7%) | |

| Age, years | 57.5 ± 9.2 | 56.9 ± 9.2 | 58.3 ± 9.3 | 0.37 |

| Male sex | 161 (81.7) | 81 (80.2) | 79 (84.0) | 0.58 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 30.0 ± 28.4 | 28.8 ± 5.4 | 31.4 ± 40.8 | 0.03 |

| Creatinine, µmol/L | 87.4 ± 16.4 | 87.2 ± 17.0 | 87.9 ± 15.6 | 0.75 |

| Current smoker | 26 (13.2) | 17 (16.8) | 9 (9.6) | 0.15 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (1.5) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (2.1) | 0.61 |

| History of stroke | 12 (6.1) | 3 (3.0) | 9 (9.6) | 0.07 |

| History of CHD (MI) | 12 (6.1) | 4 (4.0) | 8 (8.5) | 0.24 |

| History of CHD (angina) | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.2) | 0.11 |

| Dyspnea at admission* | 146 (74.1) | 70 (69.3) | 76 (80.9) | 0.05 |

| LV ejection fraction | 61.7 ± 8.8 | 61.1 ± 8.4 | 62.7 ± 9.7 | 0.67 |

| LA surface area, cm2 | 19.4 ± 5.5 | 20.34 ± 5.7 | 18.4 ± 5.0 | 0.004 |

| RA surface area, cm2 | 16.7 ± 4.8 | 17.7 ± 5.2 | 15.6 ± 4.2 | 0.007 |

| Ablation time, min | 52.4 ± 18.2 | 57.1 ± 18 | 46.9 ± 15.8 | <0.001 |

| NT-proBNP D0, pg/mL | 136 (64–429) | 168 (64–524) | 106 (65–371) | 0.3 |

| hs-CRP D0, mg/dL | 1.69 (0.78–3.4) | 2.12 (0.82–4.3) | 1.51 (0.76–2.55) | 0.09 |

| Biomarker evolution | ||||

| NT-proBNP D1, pg/mL | 220.7 (128–364) | 254.4 (153–391) | 177.8 (105–301) | 0.01 |

| NT-proBNP M6, pg/mL | 89 (41–222) | 106.3 (58–222) | 62 (37–149) | 0.001 |

| hs-CRP M6, mg/dL | 1.4 (0.74–3.17) | 1.5 (0.83–3.69) | 1.3 (0.66–2.52) | 0.09 |

Data are presented as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range for continuous variables and as n (%) for categorical variables. The Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test and Fisher’s exact test were used based on the continuous or categorical nature and normal or non-normal distribution of the variables. AF, atrial fibrillation; CHD, coronary heart disease; MI, myocardial infarction; LV, left ventricular; LA, left atrial; RA, right atrial; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; D0, the day preceding radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation (RCAAF); D1, the day following RCAAF; M6, 6 months after RCAAF. *New York Heart Association class II and III heart failure.

The primary endpoint of documented AF or typical/atypical atrial flutter recurrence occurred in 94 patients (48.2%) during the 6-month follow-up period. In the univariate analysis, patients with and without recurrence at 6 months had no significant differences in age, sex, body mass index, atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk factors, or left ventricular ejection fraction. In contrast, patients with AF recurrence had a larger left atrial surface than patients without recurrence (20.34 ± 5.7 vs. 18.4 ± 5.0 cm2, respectively; P = 0.004), a larger right atrial surface (17.7 ± 5.2 vs. 15.6 ± 4.2 cm2, respectively; P < 0.007), and a longer total radiofrequency ablation time (57.1 ± 18 vs. 46.9 ± 15.8 minutes, respectively; P < 0.001). Dyspnea at admission was significantly less frequent in patients with than without AF recurrence (69% vs. 81%, respectively; P = 0.047). The NT-proBNP level at 6 months after RCAAF was significantly higher in patients with than without AF recurrence (P = 0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum) (Table 1).

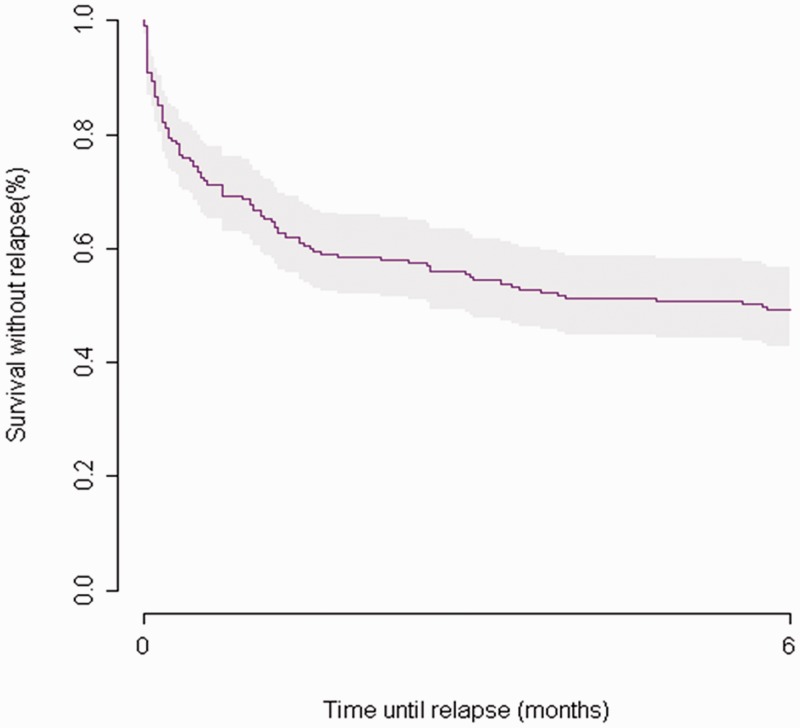

The Cox regression model included the baseline levels of NT-proBNP and hs-CRP, ablation time (in minutes), and left and right atrial surfaces with adjustment for sex, age, and dyspnea at baseline. The baseline NT-proBNP and hs-CRP levels were not associated with AF recurrence or atrial flutter in the multivariate Cox regression analysis (Tables 2 and 3). When the analysis was limited to patients with an hs-CRP level of <10 mg/L (n = 175), the baseline hs-CRP level and ablation time were significantly associated with the risk of recurrence [hazard ratio (HR), 1.12; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.01–1.24; P = 0.03 and HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01–1.03; P < 0.001, respectively]. The adjusted HRs were not significant for right and left atrial size in the multivariate analysis, although these were significant univariate predictors of AF recurrence. To account for possible collinearity between the NT-proBNP level and atrial size, interaction terms were tested but did not significantly modify the results. The adjusted HRs calculated for the 11 AF recurrence events 3 months after RCAAF indicated no clinically or statistically significant associations; 89% of events occurred during the first 3 months of follow-up (Figure 1, Kaplan–Meier survival curve for recurrence).

Table 2.

Analysis of baseline characteristics based on atrial fibrillation recurrence.

| Non-adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value (log-rank) | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | ||

| Age | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 0.4 |

| Male sex | 1.26 (0.77–2.06) | 0.35 |

| Body mass index | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.61 |

| Creatinine level | 0.82 (0.42–1.57) | 0.53 |

| Current smoker | 1.47 (0.88–2.49) | 0.14 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.6 (0.08–4.34) | 0.61 |

| History of stroke | 0.39 (0.12–1.24) | 0.09 |

| History of CHD (MI) | 0.54 (0.2–1.47) | 0.22 |

| History of CHD (angina) | – | 0.11 |

| Dyspnea at admission* | 0.61 (0.40–0.93) | 0.02 |

| LV ejection fraction | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.53 |

| LA surface area | 1.04 (1.01–1.08) | 0.01 |

| RA surface area | 1.06 (1.02–1.11) | 0.00 |

| Ablation time | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | <0.001 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CHD, coronary heart disease; MI, myocardial infarction; LV, left ventricular; LA, left atrial; RA, right atrial. *New York Heart Association class II and III heart failure.

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox regression risk analysis of recurrence at 6 months (all recurrences).

| Adjusted HR All recurrences (85 events) |

||

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| NT-proBNP D0 | ||

| All patients (for 1 pg/mL) | 0.999 (0.999–1.000) | 0.63 |

| hs-CRP < 10 mg/L (for 1 pg/mL) | 0.999 (0.999–1.000) | 0.71 |

| hs-CRP D0 | ||

| All patients (for 1 mg/dL) | 1.005 (0.97–1.037) | 0.74 |

| hs-CRP < 10 mg/L (for 1 mg/dL) | 1.12 (1.01–1.24) | 0.03 |

| Ablation time (min) | ||

| All patients | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | <0.001 |

| hs-CRP < 10 mg/L | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | <0.001 |

| LA surface area (cm2) | ||

| All patients | 1.01 (0.96–1.05) | 0.77 |

| hs-CRP < 10 mg/L | 0.99 (0.95–1.04) | 0.87 |

| RA surface area (cm2) | ||

| All patients | 1.04 (0.98–1.09) | 0.16 |

| hs-CRP < 10 mg/L | 1.04 (0.99–1.02) | 0.09 |

| Dyspnea | ||

| All patients | 0.88 (0.5–1.5) | 0.63 |

| hs-CRP < 10 mg/L | 1.04 (0.6–1.8) | 0.87 |

Analysis was performed for all patients and for patients with an hs-CRP level of <10 mg/L. The Cox regression model included NT-proBNP D0, CRP D0, ablation time (min), and LA surface area with adjustment for sex, age, and dyspnea. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; LA, left atrial; RA, right atrial; D0, the day preceding radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve for atrial fibrillation or flutter recurrence after a single RCAAF procedure, with 89% of events occurring within the first 3 months.

Considering the correlations among repeated measures taken from a given individual and integrating baseline biomarker levels, adjusted Cox regression models that included an interaction value for the baseline NT-proBNP and hs-CRP levels (Table 4) showed that every incremental 10-pg/mL increase in the NT-proBNP level on day 1 vs. day 0 was associated with an increased HR for arrhythmia recurrence (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01–1.03; P = 0.004). Furthermore, the NT-proBNP levels at 6 months were significantly lower than at baseline (Table 1) but were still associated with an increased HR for arrhythmia recurrence (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.001–1.014; P = 0.03) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted HRs for AF recurrence according to NT-proBNP and hs-CRP levels.

| Unadjusted HR |

Adjusted HR |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| NT-proBNP D0 (for 10 pg/mL) | 1.00 (0.9–1.0) | 0.9 | 0.999 (0.994–1.003)(1) | 0.63 |

| NT-proBNP D1 (for 10 pg/mL) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.13 | 1.02 (1.01–1.03)(2) | 0.004 |

| NT-proBNP M6 (for 10 pg/mL) | 1.01 (1.004–1.013) | <0.001 | 1.01 (1.001–1.014)(3) | 0.03 |

| hs-CRP D0 (for 10 mg/dL) | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | 0.2 | 1.05 (0.77–1.44)(1) | 0.73 |

| hs-CRP M6 (mg/dL) | 1.05 (0.75–1.47) | 0.78 | 1.03 (0.98–1.08)(4) | 0.2 |

(1)Adjusted HR for NT-proBNP D0, hs-CRP D0, ablation time, LA surface area, RA surface area, sex, age, and dyspnea

(2)Adjusted HR for NT-proBNP D0, CRP D0, ablation time, LA surface area, RA surface area, sex, age, dyspnea, and BNP D0 × BNP D1 interaction (P = 0.01)

(3)Adjusted HR for NT-proBNP D0, hs-CRP D0, ablation time, LA surface area, RA surface area, sex, age, dyspnea, and BNP D0 × BNP M6 interaction (P = 0.4)

(4)Adjusted HR for NT-proBNP D0, hs-CRP D0, ablation time, LA surface area, RA surface area, sex, age, dyspnea, and hs-CRP D0 × hs-CRP M6 interaction (P = 0.2)

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; AF, atrial fibrillation; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; LA, left atrial; RA, right atrial; D0, the day preceding radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation (RCAAF); D1, the day following RCAAF; M6, 6 months after RCAAF.

Discussion

In the present study, the immediate post-RCAAF and 6-month post-RCAAF NT-proBNP levels were associated with an increase in recurrence of AF or typical/atypical atrial flutter. Furthermore, the baseline hs-CRP level was associated with an increased risk of overall AF recurrence at 6 months in patients with a baseline CRP level of <10 mg/L. Indeed, the NT-proBNP levels at 6 months after RCAAF were significantly lower, albeit significantly higher relative values were measured in patients with AF recurrence, further suggesting an association between NT-proBNP and AF recurrence. Our 6-month recurrence rate corresponds to a 52% rate of absence of recurrence, but 89% of events occurred during the first 3 months of follow-up. Although the success rates reported in the literature appear higher than these, they are not necessarily directly comparable because they generally refer to longer-term results and not immediate ones.

Markers of systemic inflammation have been shown to be associated with AF, but few studies have demonstrated how the pre-ablation levels of these markers can be used to predict AF recurrence following RCAAF.20 One of the aims of this study was to determine whether the pre- or post-AF ablation levels of NT-proBNP and CRP are predictive of recurrence, with the goal of optimizing RCAAF patient selection and subsequent management. Certainly, the extent of ablation and the degree of tissue damage (e.g., reversible edema vs. irreversible coagulative necrosis) also play a significant role in the recurrence of AF. However, our subgroup analysis showed that after adjusting for procedural variables and the left atrial surface size, the post-ablation NT-proBNP and pre-ablation hs-CRP levels were possible predictors of AF recurrence in our prospective multicenter population of patients eligible for RCAAF.

The relatively high morbidity linked to AF recurrence after RCAAF is a major drawback to this approach to AF management. Our study suggests that inflammatory biomarker levels may enable stratification of the risk of recurrence, thus allowing better patient selection for RCAAF and optimized post-intervention monitoring. This in turn might significantly impact the duration of post-ablation anticoagulation and anti-arrhythmic drug therapies.

The importance of NT-proBNP as a predictor of the development of AF was shown in a previous study.26 Although our study population is distinct from a general AF population in that all patients had been specifically selected for RCAAF, our study partly corroborates these findings despite the fact that the baseline NT-proBNP level was not associated with the risk of recurrence. NT-proBNP is an inactive cleavage product of the precursor protein pre-proBNP, the other product being BNP, a regulatory neurohormone for the cardiovascular system. NT-proBNP is a marker of ventricular stretch and is predominantly produced in the ventricular and atrial myocardium and in smaller proportions by the brain (from which it takes its name).27–38 Supraventricular tachyarrhythmias and specifically AF and atrial flutter have been correlated with an increase in the tissue expression levels of natriuretic factors such as BNP, NT-proBNP, and atrial natriuretic peptide.39,40 Furthermore, it has been suggested that elevated levels of these circulating biomarkers are associated with a high level of recurrence of AF after cardioversion.41,42 These biomarkers are elevated in patients with these arrhythmias independent of the presence of heart failure.43,44 Furthermore, they are predictive markers of the risk of thromboembolic complications.45,46 Surgical AF ablation (or the Maze procedure) has also been correlated with a decrease in the level of circulating natriuretic factors.47,48 The role of NT-proBNP in the pathogenesis of AF, be it causal or simply associated with AF, therefore remains of clinical interest.

Independent of other risk factors, inflammation as measured by the CRP level is associated with AF, and this association appears to be robust.49–51 The exact mechanism by which inflammation confers a risk for the development of AF is not clear, but local atrial inflammation in the context of fibrosis in certain models has been described.17,52 Both systemic and local inflammation appear to influence the development of AF in various situations, including the postoperative period following cardiac and other types of surgery.21,51,53 Further pathophysiologic research also suggests that structural abnormalities can affect the extracellular matrix, myocytes, and endocardial remodeling, including increased fibrosis and inflammatory changes.54,55 The CRP level is elevated in patients with AF and predicts successful cardioversion.21,24,56 Chronic elevation of CRP and other inflammatory biomarkers has been shown to be a marker of systemic inflammation and predictive of an increased risk of incident myocardial infarction and stroke.57–60 CRP may also have prothrombotic effects and influence clinical outcomes through other mechanisms. Before the present study, however, the CRP level had not been evaluated as a marker for predicting AF recurrence prior to RCAAF.

The limitations of this study are related in part to its specific cohort design, which lacked a non-RCAAF control group, as well as the limited sample size. However, the prospective follow-up enabled multiple comparisons within groups of patients (e.g., AF recurrence versus no AF recurrence), thereby providing an informed perspective on these baseline values. Although the NT-proBNP level at 1 day and at 6 months after RCAAF was associated with a statistically significant increase in the risk of arrhythmia recurrence, the HRs were small and the definite clinical significance may remain limited. A further limitation of our study is that patients with different subtypes of AF ranging from paroxysmal to long-standing persistent AF were enrolled without a standard management plan; in particular, no standardized ablation line protocol was implemented beyond pulmonary vein ablation. Identifying a clear subset of patients, establishing a clear ablation strategy, and ensuring better characterized outcomes may have improved the sensitivity of this study. Notably, most patients (approximately 80%) were men, and although sex was included in our multivariate modules, this distribution limits generalization of the results to women.

Conclusions

The baseline CRP and immediate post-ablation NT-proBNP levels appear to be useful markers for overall AF recurrence after RCAAF. This confirms growing data on the role of inflammation in AF. Although the pathophysiology of these markers remains unclear, CRP may be a promising stratification tool for patient selection, and NT-proBNP may help in post-procedure management planning. Further investigation is required to determine the cause of these elevated biomarker levels in this population and to confirm their usefulness in patient care.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by an internal grant from the Department of General Internal Medicine, University Hospitals Geneva.

References

- 1.Kannel WB, Abbott RD, Savage DD, et al. Epidemiologic features of chronic atrial fibrillation: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med 1982; 306: 1018–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ, et al. Prevalence, incidence, prognosis, and predisposing conditions for atrial fibrillation: population-based estimates. Am J Cardiol 1998; 82: 2N–9N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furberg CD, Psaty BM, Manolio TA, et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in elderly subjects (the Cardiovascular Health Study). Am J Cardiol 1994; 74: 236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, et al. Probability of stroke: a risk profile from the Framingham study. Stroke 1991; 22: 312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reisinger J, Gatterer E, Heinze G, et al. Prospective comparison of flecainide versus sotalol for immediate cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 1998; 81: 1450–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1825–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Gelder IC, Hagens VE, Bosker HA, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with recurrent persistent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1834–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boriani G, Biffi M, Capucci A, et al. Conversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm: effects of different drug protocols. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1998; 21(11 Pt 2): 2470–2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh S, Zoble RG, Yellen L, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral dofetilide in converting to and maintaining sinus rhythm in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter: the symptomatic atrial fibrillation investigative research on dofetilide (SAFIRE-D) study. Circulation 2000; 102: 2385–2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jais P, Weerasooriya R, Shah DC, et al. Ablation therapy for atrial fibrillation (AF): past, present and future. Cardiovasc Res 2002; 54: 337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah DC, Haissaguerre M, Jais P, et al. Atrial flutter: contemporary electrophysiology and catheter ablation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1999; 22: 344–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jais P, Haissaguerre M, Shah DC, et al. A focal source of atrial fibrillation treated by discrete radiofrequency ablation. Circulation 1997; 95: 572–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen SA, Hsieh MH, Tai CT, et al. Initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating from the pulmonary veins: electrophysiological characteristics, pharmacological responses, and effects of radiofrequency ablation. Circulation 1999; 100: 1879–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haissaguerre M, Shah DC, Jais P, et al. Electrophysiological breakthroughs from the left atrium to the pulmonary veins. Circulation 2000; 102: 2463–2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC, et al. Electrophysiological end point for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation initiated from multiple pulmonary venous foci. Circulation 2000; 101: 1409–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brodsky MA, Allen BJ, Capparelli EV, et al. Factors determining maintenance of sinus rhythm after chronic atrial fibrillation with left atrial dilatation. Am J Cardiol 1989; 63: 1065–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schotten U, Verheule S, Kirchhof P, et al. Pathophysiological mechanisms of atrial fibrillation: a translational appraisal. Physiol Rev 2011; 91: 265–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Issac TT, Dokainish H, Lakkis NM. Role of inflammation in initiation and perpetuation of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review of the published data. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50: 2021–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aviles RJ, Martin DO, Apperson-Hansen C, et al. Inflammation as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2003; 108: 3006–3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Letsas KP, Weber R, Burkle G, et al. Pre-ablative predictors of atrial fibrillation recurrence following pulmonary vein isolation: the potential role of inflammation. Europace 2009; 11: 158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung MK, Martin DO, Sprecher D, et al. C-reactive protein elevation in patients with atrial arrhythmias: inflammatory mechanisms and persistence of atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2001; 104: 2886–2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson JL, Allen Maycock CA, Lappe DL, et al. Frequency of elevation of C-reactive protein in atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2004; 94: 1255–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richards AM, Lainchbury JG, Troughton RW, et al. Plasma amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide predicts postcardioversion reversion to atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 41: 99.

- 24.Dernellis J, Panaretou M. C-reactive protein and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: evidence of the implication of an inflammatory process in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Acta Cardiol 2001; 56: 375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnabel RB, Wild PS, Wilde S, et al. Multiple biomarkers and atrial fibrillation in the general population. PLoS One 2014; 9: e112486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patton KK, Ellinor PT, Heckbert SR, et al. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide is a major predictor of the development of atrial fibrillation: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation 2009; 120: 1768–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossi A, Enriquez-Sarano M, Burnett JC, Jr., et al. Natriuretic peptide levels in atrial fibrillation: a prospective hormonal and Doppler-echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35: 1256–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellinor PT, Low AF, Patton KK, et al. Discordant atrial natriuretic peptide and brain natriuretic peptide levels in lone atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 45: 82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shin DI, Jaekel K, Schley P, et al. Plasma levels of NT-pro-BNP in patients with atrial fibrillation before and after electrical cardioversion. Z Kardiol 2005; 94: 795–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al. Plasma natriuretic peptide levels and the risk of cardiovascular events and death. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 655–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonagh TA, Robb SD, Murdoch DR, et al. Biochemical detection of left-ventricular systolic dysfunction. Lancet 1998; 351: 9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cowie MR, Struthers AD, Wood DA, et al. Value of natriuretic peptides in assessment of patients with possible new heart failure in primary care. Lancet 1997; 350: 1349–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clerico A, Iervasi G, Del Chicca MG, et al. Circulating levels of cardiac natriuretic peptides (ANP and BNP) measured by highly sensitive and specific immunoradiometric assays in normal subjects and in patients with different degrees of heart failure. J Endocrinol Invest 1998; 21: 170–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Omland T, Aakvaag A, Bonarjee VV, et al. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide as an indicator of left ventricular systolic function and long-term survival after acute myocardial infarction. Comparison with plasma atrial natriuretic peptide and N- terminal proatrial natriuretic peptide. Circulation 1996; 93: 1963–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krishnaswamy P, Lubien E, Clopton P, et al. Utility of B-natriuretic peptide levels in identifying patients with left ventricular systolic or diastolic dysfunction. Am J Med 2001; 111: 274–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maisel A. B-type natriuretic peptide levels: a potential novel “white count” for congestive heart failure. J Card Fail 2001; 7: 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lubien E, DeMaria A, Krishnaswamy P, et al. Utility of B-natriuretic peptide in detecting diastolic dysfunction: comparison with Doppler velocity recordings. Circulation 2002; 105: 595–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inoue S, Murakami Y, Sano K, et al. Atrium as a source of brain natriuretic polypeptide in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Card Fail 2000; 6: 92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oliver JR, Twidale N, Lakin C, et al. Plasma atrial natriuretic polypeptide concentrations during and after reversion of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardias. Br Heart J 1988; 59: 458–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roy D, Paillard F, Cassidy D, et al. Atrial natriuretic factor during atrial fibrillation and supraventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol 1987; 9: 509–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mookherjee S, Anderson G, Jr., Smulyan H, et al. Atrial natriuretic peptide response to cardioversion of atrial flutter and fibrillation and role of associated heart failure. Am J Cardiol 1991; 67: 377–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohta Y, Shimada T, Yoshitomi H, et al. Drop in plasma brain natriuretic peptide levels after successful direct current cardioversion in chronic atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol 2001; 17: 415–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tuinenburg AE, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Boomsma F, et al. Comparison of plasma neurohormones in congestive heart failure patients with atrial fibrillation versus patients with sinus rhythm. Am J Cardiol 1998; 81: 1207–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wozakowska-Kaplon B, Opolski G. Atrial natriuretic peptide level after cardioversion of chronic atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 2002; 83: 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sato Y, Maruoka H, Honda Y, et al. Plasma concentrations of atrial natriuretic peptide in cardioembolic stroke with atrial fibrillation. Kurume Med J 1995; 42: 71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shimizu H, Murakami Y, Inoue S, et al. High plasma brain natriuretic polypeptide level as a marker of risk for thromboembolism in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Stroke 2002; 33: 1005–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakamura M, Niinuma H, Chiba M, et al. Effect of the maze procedure for atrial fibrillation on atrial and brain natriuretic peptide. Am J Cardiol 1997; 79: 966–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim KB, Lee CH, Kim CH, et al. Effect of the Cox maze procedure on the secretion of atrial natriuretic peptide. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998; 115: 139–146; discussion 146-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ellinor PT, Low A, Patton KK, et al. C-Reactive protein in lone atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2006; 97: 1346–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pirat B, Atar I, Ertan C, et al. Comparison of C-reactive protein levels in patients who do and do not develop atrial fibrillation during electrophysiologic study. Am J Cardiol 2007; 100: 1552–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marott SC, Nordestgaard BG, Zacho J, et al. Does elevated C-reactive protein increase atrial fibrillation risk? A Mendelian randomization of 47,000 individuals from the general population . J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56: 789–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hanna N, Cardin S, Leung TK, et al. Differences in atrial versus ventricular remodeling in dogs with ventricular tachypacing-induced congestive heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 2004; 63: 236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aranki SF, Shaw DP, Adams DH, et al. Predictors of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery surgery. Current trends and impact on hospital resources. Circulation 1996; 94: 390–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the task force for the management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2010; 31: 2369–2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nattel S. New ideas about atrial fibrillation 50 years on. Nature 2002; 415: 219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu T, Li G, Li L, et al. Association between C-reactive protein and recurrence of atrial fibrillation after successful electrical cardioversion: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49: 1642–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morrow DA, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, inflammation, and coronary risk. Med Clin North Am 2000; 84: 149–161, ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ridker PM. Novel risk factors and markers for coronary disease. Adv Intern Med 2000; 45: 391–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, et al. C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 836–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, et al. Plasma concentration of interleukin-6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation 2000; 101: 1767–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]