Abstract

The α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7-nAChR) is a ligand-gated ion channel that is expressed widely in vertebrates and is the principal high-affnity α-bungarotoxin (α-bgtx) binding protein in the mammalian CNS. α7-nAChRs associate with proteins that can modulate its properties. The α7-nAChR interactome is the summation of proteins interacting or associating with α7-nAChRs in a protein complex. To identify an α7-nAChR interactome in neural tissue, we isolated α-bgtx-affnity protein complexes from wild-type and α7-nAChR knockout (α7 KO) mouse whole brain tissue homogenates using α-bgtx-affnity beads. Affnity precipitated proteins were trypsinized and analyzed with an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer. Proteins isolated with the α7-nAChR specific ligand, α-bgtx, were determined to be α7-nAChR associated proteins. The α7-nAChR subunit and 120 additional proteins were identified. Additionally, 369 proteins were identified as binding to α-bgtx in the absence of α7-nAChR expression, thereby identifying nonspecific proteins for α7-nAChR investigations using α-bgtx enrichment. These results expand on our previous investigations of α7-nAChR interacting proteins using α-bgtx-affnity bead isolation by controlling for differences between α7-nAChR and α-bgtx-specific proteins, developing an improved protein isolation methodology, and incorporating the latest technology in mass spectrometry. The α7-nAChR interactome identified in this study includes proteins associated with the expression, localization, function, or modulation of α7-nAChRs, and it provides a foundation for future studies to elucidate how these interactions contribute to human disease.

Keywords: nicotine, Orbitrap Fusion, mass spectrometry, interactome, proteomics, nAChR, α-bungarotoxin

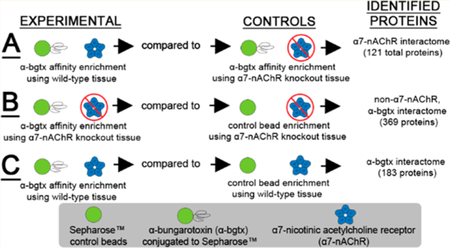

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The ligand-gated ion channel (LGIC) superfamily comprises a diverse array of structurally similar ionotropic receptors, including nicotinic acetylcholine, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A, GABAC, glycine, and 5-HT3 serotonin receptors.1,2 Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are pentameric cation channels expressed widely in the mammalian brain and neuromuscular junction.3 Neuronal-type nAChRs are also found in several non-neuronal cell types, including leukocytes.4 Eleven neuronal nAChR subunits have been identified in mammals (α2–7, α9–10, β2–4).5 Receptors containing α4β2, α3β4, and α7 subunits are the most prevalent in the mammalian CNS, with α7-nAChRs being the most widely expressed homomeric nAChR.3 The α7-nAChR, composed of five α7 subunits, has several unique physiological traits distinguishing it from other receptor subtypes. For example, the α7-nAChR has a higher Ca2+:Na+ permeability ratio than other nAChR subtypes, suggesting a greater physiological role in Ca2+ signaling pathways.1,6

The investigation of α7-nAChRs has been facilitated by the availability of several high-affnity, selective ligands, including α-bungarotoxin (α-bgtx) and methyllycaconitine (MLA). Radiolabeled α-bgtx and MLA binding in murine brain tissue has been used extensively to establish α7-nAChR levels and distribution.7,8 Studies using 125I-α-bgtx have investigated changes in α7-nAChR expression during development, as well as drug-induced changes in α7-nAChR expression in whole brain and specific brain regions.9,10 Interstrain variability of α7-nAChR levels and distribution has also been investigated using radiolabeled α-bgtx.11 α-Bgtx is well-characterized as having high-affnity (nM Kd) for α7-nAChRs, and as such is a reliable, commercially available ligand for affnity purification of α7-nAChRs.

Proteins associating with a target of interest, in our case α7-nAChR, are collectively known as an interactome. Receptor interactomes may include both direct interactions with the receptor and indirect interactions with the receptor-protein complex. Certain receptor-protein interactions regulate receptor biogenesis and function. These protein interactions may impact α7-nAChR assembly,12 affect traffcking and targeting,13,14 contribute to signaling,15 and/or be medically relevant.16,17 Mass spectrometry-based protein identification is a well-established and valuable tool for determining protein interactomes.18,19

The murine brain is an ideal model for the investigation of α7-nAChR interacting proteins, as various strains and genotypes are readily available for study, and technologies to establish new transgenic and mutant mouse models have been developed. The described work expands on prior proteomic studies using α-bgtx as a tool for affnity purification of α7-nAChRs. Here, we incorporate several new methods enabling the reliable detection of murine α7-nAChRs and associated proteins, and we explore both α7-nAChR and α-bgtx-specific protein controls.20

Several proteomic comparisons are described in our investigation. The first comparison is an analysis of α-bgtx-affnity purified proteins from wild-type and α7 KO mice. This comparison allows identification of α7-nAChR specific interacting proteins. The second comparison is an analysis of proteins that bind to α-bgtx in the absence of α7-nAChRs, using α7 KO mice to identify those proteins that do not interact with α7-nAChRs, but that do interact with α-bgtx-affnity beads. The GABAA receptor (GABAAR) has recently been shown to have affnity for α-bgtx in mouse tissue.21 Given this, the use of α7-nAChR-specific controls, rather than α-bgtx-specific controls, is of paramount importance for proteomic investigations when using α-bgtx-affnity purification to exclude non-α7-nAChR, α-bgtx interacting proteins. Some of the previously reported α7-nAChR associated proteins may, in fact, associate with another α-bgtx-affnity protein and not with the α7-nAChR.

In summary, the work described here defines a murine whole brain α7-nAChR interactome, while also identifying the receptor subunit itself. Additionally, the availability of α7 KO mice and α-bgtx immobilization techniques allows for the identification of α-bgtx-affnity proteins that should not be included in the α7-nAChR interactome.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Mouse Brain Tissue

Whole brains of adult, male, wild-type C57Bl/6 or FVB mice, as well as adult, male, α7 KO FVB mice, were isolated and frozen at −80 °C before use. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Brown University (protocol 1201004).

Preparation of α-bgtx-Sepharose Affnity Beads

Cyanogen bromide-activated Sepharose beads 4B (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (1g) were hydrated in 5 mL of cold 1 mM HCl for 30 min and washed with 500 mL of 1 mM HCl over a coarse glass filter. The beads were added to 7.5 mL coupling buffer (0.25 M NaHCO3, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 8.3) and subsequently centrifuged at 4 °C for 5 min at 1500g. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellets were resuspended in 7.5 mL coupling buffer containing 4 mg of α-bgtx (0.53 mg α-bgtx/ml coupling buffer/g Sepharose 4B beads). Bead/ligand mixtures were incubated with gentle agitation at 4 °C for 18 h. The beads were subsequently pelleted and resuspended in 7.5 mL of 0.2 M glycine in 80% coupling buffer and 20% ultrapure water, and they were gently agitated overnight at 4 °C to block unreacted groups on the beads. The beads were then washed over a coarse glass filter, first with 100 mL of 0.1 M NaHCO3, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 8.0, then 100 mL of 0.1 M NaCH3CO2, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 4.0, again with 100 mL of 0.1 M NaHCO3, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 8.0, 100 mL coupling buffer, and last twice with 100 mL Tris-buffered saline (TBS: 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5). Washed beads were resuspended in TBS for storage at 4 °C. Prior to use, stock α-bgtx-affnity beads were uniformly resuspended into a slurry, and aliquots were centrifuged at 4 °C for 5 min at 1500g. Pelleted beads were resuspended to make a 50/50 slurry with homogenization buffer (50 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, pH 7.4) before use.

Mouse Whole Brain Membrane Protein Solubilization

Mouse whole brains were dissociated in homogenization buffer (50 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, pH 7.4) with 30 strokes of a Potter-Elvehjem glass homogenizer on ice. Membrane fragments were isolated following centrifugation at 97 000g for 60 min at 4 °C. Membrane pellets were then treated with solubilization buffer (50 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 2% Triton X-100, pH 7.4) with 40 strokes of a Potter-Elvehjem glass homogenizer on ice and incubated for 3 h at 4 °C with agitation to solubilize membrane-bound proteins. Following a second centrifugation at 100 000g for 60 min at 4 °C, the solubilized membrane fraction was recovered in the supernatant. All buffers used to isolate the solubilized membrane fraction were supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Protein content of solubilized membrane fractions was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce, Waltham, MA).

α7-nAChR and Associated Protein Complex Isolation

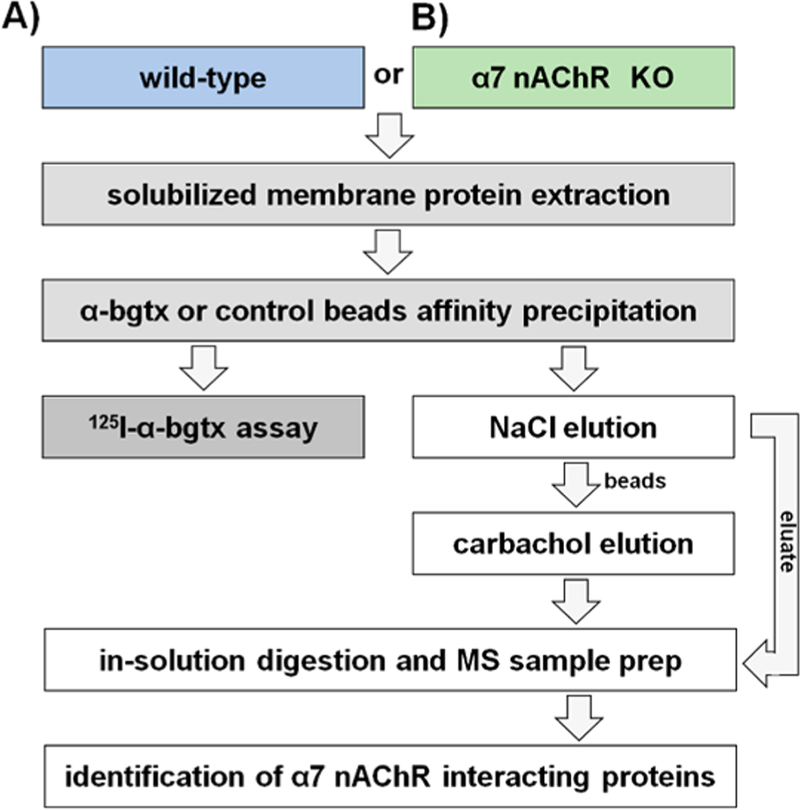

Immediately following the isolation of solubilized membrane fractions, a volume containing 25 mg of solubilized protein was incubated with 200 μL of the 50/50 α-bgtx-affnity bead/ homogenization buffer slurry for 18 h at 4 °C with gentle agitation. α-Bgtx-affnity beads were washed with homogenization buffer before use. Control samples were either solubilized receptor preparations from α7 KO mice (i.e., α7-nAChR-specific control) or control beads lacking conjugated α-bgtx (i.e., α-bgtx-specific control) (Figure 1). Following the incubation, α-bgtx-affnity beads and bound protein were transferred to Pierce Spin Cups (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) and washed three times with solubilization buffer. After the beads and bound protein were washed, the total affnity-immobilized α7-nAChR content was either measured using a 125I-α-bgtx radioligand binding assay, or the isolated proteins were eluted for mass spectrometry analysis (Figure 2).

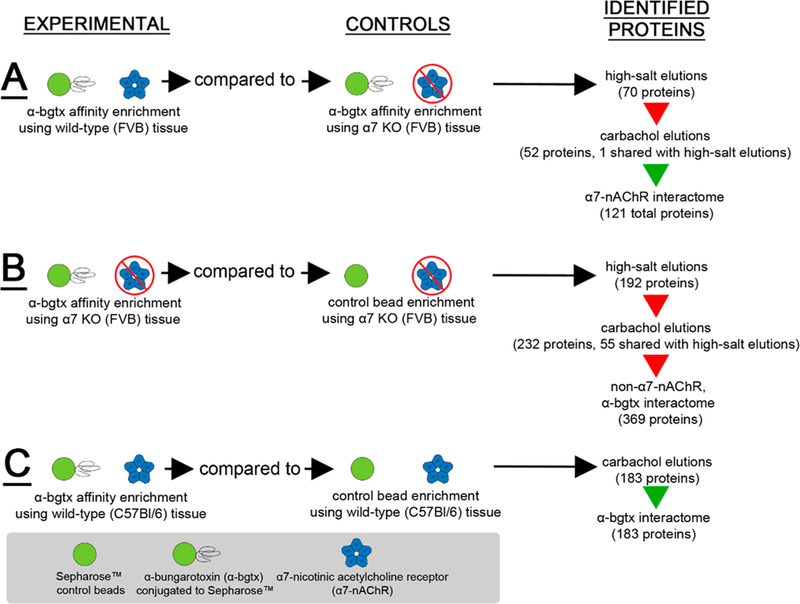

Figure 1.

Murine whole brain experimental design. Solubilized protein was isolated from male (A) wild-type or (B) α7 KO mice and was incubated with Sepharose α-bgtx-affnity beads or Sepharose beads without α-bgtx (i.e., control beads). The α7-nAChR interactome was identified using FVB α7 KO extracts as α7-nAChR-specific controls, which were analyzed in parallel with FVB wild-type samples. For non-α7-nAChR, α-bgtx interactome investigations, proteins were identified from α7 KO FVB mice incubated with α-bgtx-affnity beads or control beads. For α-bgtx interactome investigations, wild-type C57Bl/6 α-bgtx-affnity enrichments were compared to C57Bl/6 extracts incubated with control beads. Protein bound to α-bgtx-affnity beads was sequentially eluted with 2 M NaCl sodium chloride and 1 M carbachol, reduced, alkylated, and digested with trypsin in-solution. The resulting peptides were analyzed with an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer, and spectra were identified using the Mascot algorithm. Data were analyzed further using ProteoIQ.

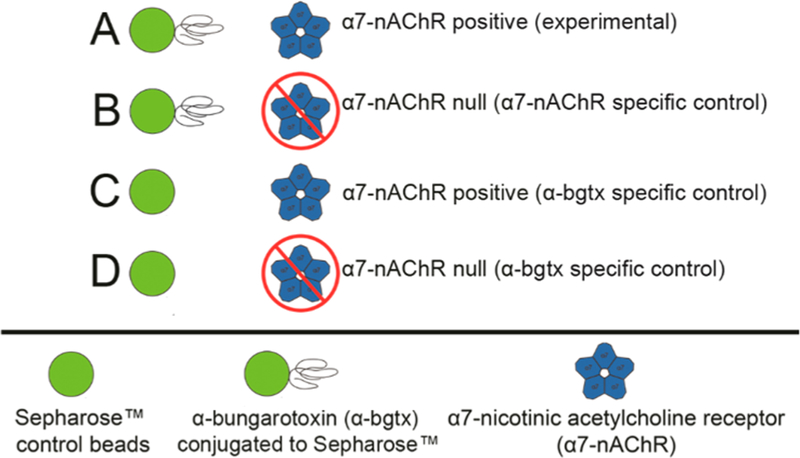

Figure 2.

α-bgtx-affnity immobilization conditions. (A) α-Bgtx-sensitive proteins were isolated from samples using wild-type mice and α-bgtx-conjugated affnity beads (i.e., α-bgtx beads). (B) Nonspecific interactions with α-bgtx beads were identified using α-bgtx binding enrichment in samples prepared from α7 KO mice. (C) Sepharose without conjugated α-bgtx (i.e., “control beads”) were used to control for nonspecific interactions to Sepharose. (D) Sepharose without conjugated α-bgtx (i.e., “control beads”) were used to control for nonspecific interactions to Sepharose in α7 KO mice samples.

Radioligand Binding Assays

An on-bead 125I-α-bgtx binding assay was used to confirm α7-nAChR presence on α-bgtx-affnity beads and the absence of α7-nAChRs on control beads. α-Bgtx is able to affnity immobilize and concurrently detect α7-nAChRs, as these receptors contain multiple α-bgtx binding sites.22 Affnity-immobilized α7-nAChR content was determined by incubating samples with 5 nM 125I-α-bgtx (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA) for 1 h at room temperature. Nonspecific binding was determined in controls by the inclusion of 1 μM unlabeled α-bgtx prior to addition of 125I-α-bgtx. Following incubation with 125I-α-bgtx, beads were washed three times with solubilization buffer and gamma emissions were measured using a Wallac 1275 minigamma gamma counter.

Mass Spectrometry Sample Preparation, Precipitation, and In-Solution Trypsin Digestion

Affnity beads were washed three times with solubilization buffer followed by a single, high-salt solubilization buffer wash (2.05 M NaCl, 50 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 2% Triton X-100, pH 7.4) to enhance the identification of α7-nAChR by eluting non-α7-nAChR protein from the affnity beads. Immobilized α7-nAChR protein complexes were specifically eluted from the α-bgtx-affnity beads by incubation with 100 μL 1 M carbachol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 20 mM HEPES, pH 8.0 for 30 min with agitation every 5 min at room temperature. α-Bgtx-affnity beads were allowed to sediment, and the eluted proteins in the supernatant were removed and stored at −80 °C until preparation for mass spectrometry analysis. The quantity of eluted protein was determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit. To prepare for mass spectrometric analysis, samples were thawed and disulfide residues were reduced with 47 mM TCEP in 20 mM HEPES, pH 8.0 for 1 h at 60 °C. Samples were alkylated with 83 mM iodoacetamide in 20 mM HEPES, pH 8.0 for 1 h in the dark at room temperature, and then concentrated and purified via precipitation using a BioRad ReadyPrep 2-D Cleanup Kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Precipitated protein was resuspended in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 7.8 supplemented with 100 ng trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) and digested overnight in-solution at 37 °C. Both high-salt solubilization buffer washes and 1 M carbachol elutions were analyzed using mass spectrometry.

HPLC and Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Each sample was desalted using a StageTip and dried via vacuum centrifugation. Peptides were reconstituted in 5% acetonitrile (ACN), 5% formic acid for LC-MS/MS analysis using an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) coupled to an in-line Proxeon EASY-nLC 1000 liquid chromatography (LC) pump (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). Peptides (approximately 2 μg) were fractionated on a microcapillary column (75 μm inner diameter) packed with ∼0.5 cm of Magic C4 resin (5 μm, 100 Å, Michrom Bioresources) followed by ∼35 cm of GP-18 resin (1.8 μm, 200 Å, Sepax, Newark, DE). Separation of peptides was achieved during a 3 h gradient of 6 to 26% ACN in 0.125% formic acid at a rate of 350 nL/min. The scan sequence began with an MS1 spectrum (Orbitrap analysis; resolution 120 000; mass range 400–1400 m/z; automatic gain control (AGC) target 2 × 105; maximum injection time 100 ms). Precursor ion selection for MS/MS analysis was performed using a TopSpeed of 2 s or TopN of 20 ions. MS/MS analysis consisted of collision-induced dissociation (CID) (quadrupole ion trap analysis; automatic gain control (AGC) 1 × 104; normalized collision energy (NCE) 35; maximum injection time 150 ms). Peak lists of MS/MS spectra were created using msconvert.exe (v. 2.2.3300) available in the ProteoWizard tool.23 Experimental spectra were bioinformatically matched in silico against theoretical spectra of a concatenated target-decoy (sequence-reversed) Mus musculus database (Uniprot, March 2015) using the Mascot algorithm (Matrix Science, Boston, MA). Database searches used the following parameters: up to two missed trypsin cleaves allowed, 7 ppm MS tolerance, 20 ppm MS/MS tolerance, fixed carbamidomethyl modification, and variable methionine oxidation modification.

Data Analysis

Mascot search results were loaded into ProteoIQ (Premier Biosoft, Palo Alto, CA) for further analysis. All identified proteins were initially filtered using a 1% protein false-discovery rate (FDR) calculated with the PROVALT algorithm and a minimum peptide length of six amino acids. Inclusion criteria for α7-nAChR and α-bgtx interacting proteins were as follows: ≥ 90% group probability score of correct identity assignment using the ProteinProphet algorithm, presence in two or more independent replicates, and 0% probability score in controls.24–26 Both the PROVALT and ProteinProphet algorithm are integrated into ProteoIQ. Only Top and Co-Top identifications (i.e., identifications that include all peptide data in a protein group) were used during analysis. For mass spectrometry analysis, each condition was analyzed with five biological replicates. Identified α7-nAChR-specific interacting proteins were categorized by their reported Gene Ontology (GO) biological process and cellular compartment terms using Search Tool for Recurring Instances of Neighboring Genes (STRING) (version 10.5), and Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (version 6.8).27,28 If neither classification system had an entry for an identified protein, the protein was classified as unattributed. STRING was used to visualize interactomes, analyze possible GO Term enrichments for cellular compartment, molecular function or biological process, as well as illustrate known connections between identified interacting proteins.28 FDRs for enriched ontologies were reported using STRING analysis. DAVID was used to identify ontologies represented in the identified proteomes that may not be enriched. Results from DAVID were reported as p-values using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure for correcting multiple comparisons.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Immobilization of α7-nAChRs and Associated Proteins Using α-bgtx-Affnity Beads

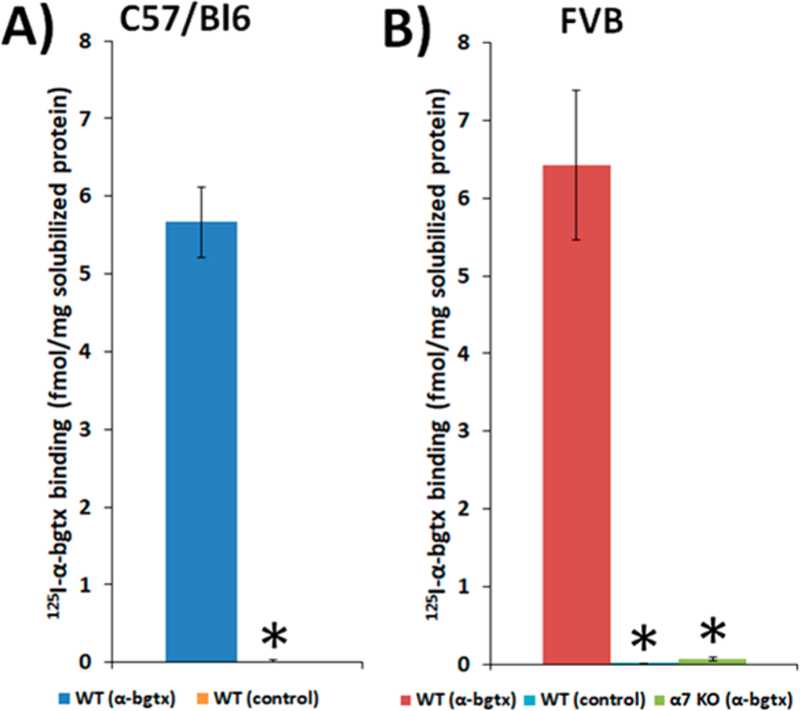

Solubilized C57Bl/6 and FVB murine brain tissue preparations from both wild-type and α7 KO FVB controls were incubated with α-bgtx-affnity beads or control beads lacking conjugated α-bgtx. Using the optimized α-bgtx-affnity immobilization conditions, 5.4 ± 0.5 fmol 125I-α-bgtx binding per mg solubilized protein was measured in samples from C57Bl/6 mouse tissue and no observable binding was detected using control beads (Figure 3A). In wild-type preparations of FVB mouse brain tissue, 6.4 ± 1 fmol 125I-α-bgtx binding per mg solubilized protein was measured, and no detectable binding was observed using α7 KO preparations or when incubating wild-type tissue with control beads (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Specific 125I-α-bgtx binding to solubilized protein isolated from C57Bl/6 and FVB solubilized murine brain tissue. Binding of 5 nM 125I-α-bgtx to protein immobilized on α-bgtx-affnity beads (4 mg α-bgtx per 1g Sepharose) incubated with male C57Bl/6 (A) and FVB (B) solubilized murine whole brain membrane fractions. Nonspecific binding was determined by the addition of 1 μM unlabeled α-bgtx to preparations prior to the addition of 125I-α-bgtx. Appreciable 125I-α-bgtx binding was observed in both C57Bl/6 and FVB strains (5.4 ± 0.5 and 6.4 ± 1 fmol 125I-α-bgtx per mg solubilized protein respectively). No appreciable binding was detected in either strain using control beads (A,B) or α7 KO FVB mice using α-bgtx-affnity beads (B). Three mice were used per condition, and extracts from each mouse were measured in duplicate. Significance between α-bgtx affnity pulldowns and either control bead or α-bgtx pulldowns from α7 KO was determined using a Student’s t-test. “*” denotes p < 0.05.

A primary aim for this work was to establish methods for identifying α7-nAChR peptides, as well as providing an updated and well-controlled α7-nAChR interactome from mouse brain tissue using α-bgtx-affnity immobilization and mass spectrometry. To achieve this aim, several methodological changes were made to our previous study design.20 In addition to the changes in homogenization/solubilization and bead conditions, a stringent “high-salt wash” (2 M NaCl, 50 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 2% Triton X-100, pH 7.4) was included prior to elution with carbachol to reduce nonspecific binding to beads. High-salt washes did not reduce α-bgtx binding to immobilized α7-nAChRs in the SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma-derived cell line that endogenously expresses α7-nAChRs (Supplemental Figure S-1).29 However, as 2 M NaCl could displace some protein interactions, the high-salt washes were also analyzed by mass spectrometry. For both the α7-nAChR and non-α7-nAChR, α-bgtx interactomes, the distinction was made between proteins that were eluted in the high-salt wash and proteins that were eluted by carbachol. A second α-bgtx interactome, only including proteins eluted with carbachol in wild-type tissue, was also investigated.

Identification of α7-nAChR Subunit Peptides and α7-nAChR Interacting Proteins

Comparing α-bgtx purified proteins from wild-type tissue with proteins purified from α7 KO tissue allowed identification of an α7-nAChR-specific interactome. Proteins from both experimental and negative control samples were removed sequentially by a high-salt wash, followed by carbachol elution. Fifty-two α7-nAChR interacting proteins were eluted with carbachol, including a peptide of the α7-nAChR subunit, FPDGQIWKPDILLYNSADER (Table 1, Supplemental Tables S-1). Seventy α7-nAChR interacting proteins were identified in high-salt washes. An interactome of 121 α7-nAChR interacting proteins was identified by combining identifications from both high-salt washes and carbachol elutions (Figure 4A). Peptides from α7 subunits were not identified in high-salt washes (Supplemental Tables S-1). A single protein, plakophilin-1, was identified in both the high-salt washes and carbachol-eluted fractions. Proteins identified as α7-nAChR interacting proteins in high-salt washes (i.e., not identified in α7 KO control samples) were not included in the α7 interactome if the protein was subsequently identified in both experimental and α7 KO controls after carbachol elution.

Table 1.

Identification of α7-nAChR and GABAAR Subunits in Carbachol-Eluted Fractionsa

| receptor subunit | accession number | experimental | control | total peptides | data sets (of 5) | probability score (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | α7 neuronal acetylcholine receptor | P49582 | FVB WT | α7 KO | 1 | 3 | 100 |

| B | α7 neuronal acetylcholine receptor | P49582 | C57Bl/6 WT | control beads | 1 | 2 | 100 |

| C | β3 γ-aminobutyric acid receptor | P63080 | C57Bl/6 WT | control beads | 3 | 3 | 100 |

| D | β1 γ-aminobutyric acid receptor | P50571 | FVB α7 KO | control beads | 2 | 3 | 100 |

Both α7-nAChR-specific and α-bgtx-specific controls were investigated for all known α-bgtx binding proteins. (A) The α7-nAChR subunit was identified comparing FVB wild-type and α7 KO brain tissue. (B, C) Both the α7-nAChR subunit and a GABAAR subunit were found in C57Bl/6 wild-type using control beads, i.e., beads lacking conjugated α-bgtx. (D) Only a GABAAR subunit was found using control beads in α7 KO brain tissue. Probability scores were measured using the ProteinProphet algorithm integrated into ProteoIQ.

Figure 4.

Summary of identified interactomes. Three interactomes were identified and categorized as (A) α7-nAChR, (B) non-α7-nAChR, α-bgtx, or (C) α-bgtx interactomes. High-salt wash-eluted and carbachol-eluted fractions were investigated in (A) and (B). Only carbachol-eluted proteins were investigated in (C). The high-salt washes were investigated to identify interacting proteins eluted before the addition of carbachol. An α7-nAChR subunit peptide was identified in the carbachol elutions of the α7-nAChR as well as in the α-bgtx interactomes (denoted by the green arrows). Peptides corresponding to α7-nAChR subunit were not identified in the high-salt wash fraction of the α7-nAChR interactome, nor in either of the non-α7-nAChR interactomes (red arrows). The total number of proteins identified using the defined inclusion criteria is listed on the right.

Several studies have previously investigated α7-nAChR interactomes using mass spectrometry.20,30,31 Paulo et al. first utilized α-bgtx-affnity beads to isolate protein complexes from wild-type and α7 KO mice to investigate the α7-nAChR interactome.20 While the methodology used in the Paulo et al. study is similar to that used here, no peptides originating from the α7-nAChR subunit were identified by mass spectrometric analysis. A second study used α-bgtx-affnity to isolate α7-nAChRs and to identify the receptor as well as their protein of interest, PMCA2, using rat brain extracts and mass spectrometry.31 However, this study did not report suffcient details on the identification of α7-nAChR peptides and did not utilize an α7-nAChR-specific control for the analysis. More recently, α7-nAChR subunit peptides have been identified, along with interacting proteins, in the rat pheochromocytoma-derived cell line PC12 using anti-α7-nAChR antibody conjugated affnity beads and mass spectrometry.30 Several commercially available antibodies for nAChRs have been reported to have inconsistent characteristics, and their use for immunoprecipitation can be problematic.32,33 α-Bgtx provides a reliable, commercially available ligand for affnity purification of α7-nAChRs.

The sequenced α7-nAChR subunit peptide, FPDGQ-IWKPDILLYNSADER, was identified in wild-type samples of both FVB and C57Bl/6 mice and was not identified in either α7-nAChR-specific and α-bgtx-specific controls (Table 1, Supplemental Tables S-1, S-8). The same peptide was identified previously in SH-SY5Y samples (not shown) and in transfected SH-EP1 cells, two human neuroblastoma-derived cell models of α7-nAChR expression.34 In addition to identifying α7-nAChRs, GABAAR subunits, recently shown to bind α-bgtx, were identified in both α-bgtx and non-α7-nAChR, α-bgtx interactomes, but not in the α7-nAChR interactome (Table 1).21,35 This observation stresses the importance of controls that are α7-nAChR-specific when using α-bgtx-affnity immobilization.

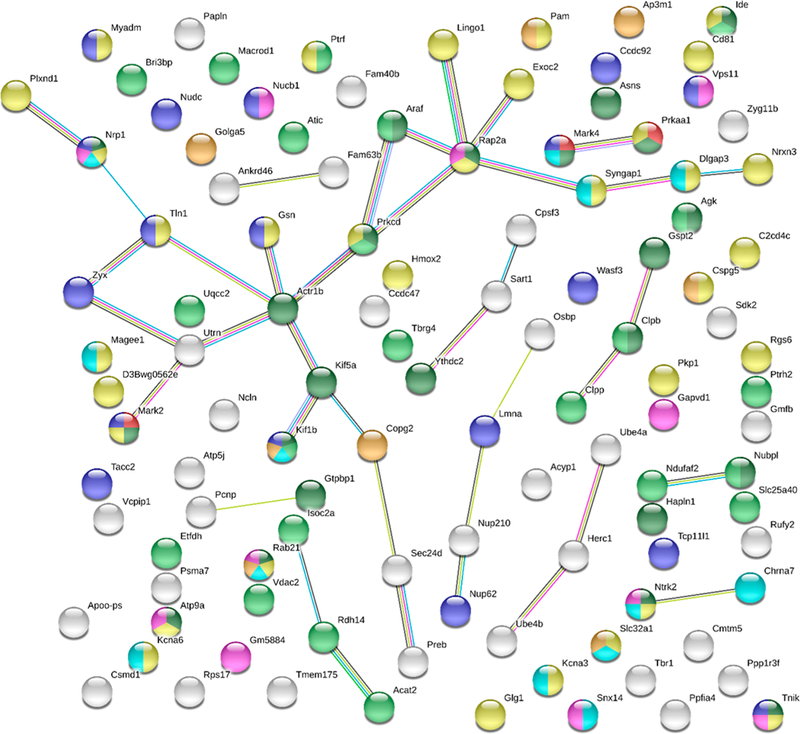

The proteins of the α7-nAChR interactome were characterized by their known or predicted cellular compartments (Supplemental Tables S-2, S-3), molecular functions (Supplemental Tables S-4, S-5), and biological processes, using both STRING and DAVID. Interactome associated Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways were identified using DAVID. STRING is useful for highlighting enriched protein characteristics in a proteome, whereas DAVID is useful for highlighting proteins of a particular characteristic, whether enriched or not. No enriched biological processes were identified by STRING or DAVID; though general biological process ontologies were identified by DAVID (Supplemental Tables S-6). STRING was used to visualize a protein–protein interaction map of the α7-nAChR interactome (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Analysis of protein–protein interactions using STRING. STRING analysis (https://string-db.org/) of total identified α7-nAChR interacting proteins. 110 of 121 total proteins had suffcient information for STRING analysis. All options for active interaction sources and a minimum interaction score of 0.4 were selected. Edge colors represent known interactions from curated databases (teal), known interactions determined from experimentation (purple), predicted interactions from gene neighborhood (green), predicted interactions from gene fusions (red), or predicted interactions from gene co-occurrence (blue). Additional edge colors denote associations determined from text mining (yellow), coexpression (black), or protein homology (light blue). Node colors representing molecular functions include tau-protein kinase activity (red) and carbohydrate derivative binding (dark green). Node colors denoting cellular component include: mitochondrion (light green), plasma membrane (yellow), neuron projection (teal), cytoplasmic vesicle membrane (gold), endosome (purple), and cytoskeleton (blue).

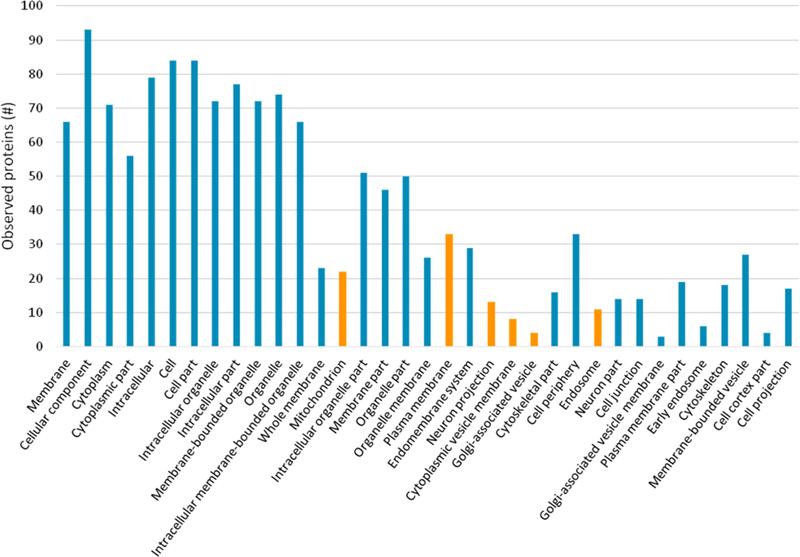

The proteins of the α7-nAChR interactome identified in this study are enriched for cellular compartments involved with receptor biogenesis (Golgi-associated vesicle, GO:0005798, FDR 0.01), traffcking (cytoplasmic vesicle membrane, GO:0030659, FDR 0.009), the receptor’s site of physiological activity (plasma membrane, GO:0005886, FDR 0.008), and receptor turnover (endosome, GO:0005768, FDR 0.012). Interestingly, localization to the mitochondria (GO:0005739, FDR 0.0004) was also enriched, agreeing with previous studies that identified α7-nAChR function in the mitochondrial membrane.36 Proteins localized in neuron projections (GO:0043005, FDR 0.008), including α7 subunits, were also enriched, which is consistent with the observation that development of neuron projections (i.e., neurites) is mediated by α7-nAChRs (Figure 5, Figure 7).37

Figure 5.

Cellular compartments enriched in the α7-nAChR interactome data identified using STRING. Proteins are identified by their gene name. GO Term identification numbers, false discovery rates, and individual matched protein names are included in Supplemental Tables S-2. Only matched cellular compartment ontologies <5% FDR are shown. Six ontologies described further in the text are highlighted in orange: mitochondrion, plasma membrane, neuron projection, cytoplasmic vesicle membrane, Golgi-associated vesicle, and endosome.

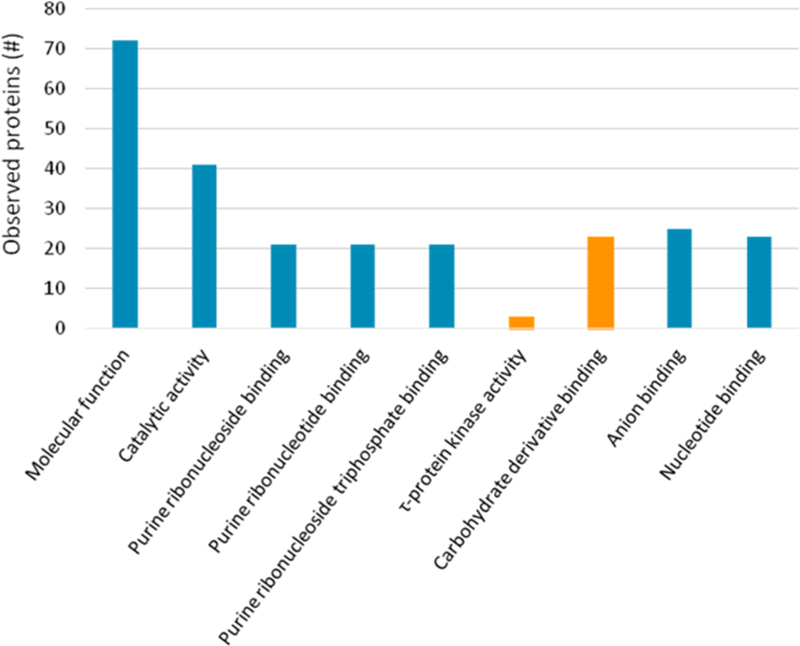

The identification of interacting proteins is an important step toward understanding where receptors were localized, their associated molecular functions, and how those functions contribute to biological processes. This understanding may help elucidate how alterations of the receptors’ interactors can lead to or contribute to human disease, as well as help identify possible therapeutic targets. STRING and KEGG pathway analysis of the identified α7-nAChR interactome showed enrichment for several molecular functions of potential relevance to human disease (Figure 6, Table 2). STRING and KEGG analysis was supplemented by a literature review to explore which α7-nAChR interacting proteins that were associated with human diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, insulin resistance, and Parkinson’s disease in the literature. Thirty-one selected human disease-related proteins were identified in the α7-nAChR interactome and are presented in Table 3.

Figure 6.

Molecular functions enriched in the α7-nAChR interactome data identified using STRING. Proteins are identified by their gene name. GO term identification numbers, false discovery rates, and individual matched protein names are included in Supplemental Tables S-4. Only matched molecular function ontologies <5% FDR are shown. Two ontologies, tau (τ)-protein kinase activity and carbohydrate derivative binding, are highlighted in orange and described further in the text.

Table 2.

KEGG Pathway Analysis of the Identified α7-nAChR Interactomea

| protein name (gene name, accession number) | unique peptides | seq cov. (%) | ion score | prob. Score (%) | KEGG pathway(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase/IMP cyclohydrolase (Atic, Q9CWJ9) ♦ | 2 | 6 | 68 | 96 | mmu00230: purine metabolism, mmu00670: one-carbon pool by folate, mmu01100: metabolic pathways, mmu01130: biosynthesis of antibiotics |

| acetyl-Coenzyme A acetyltransferase 2 (Acat2, Q8CAY6) ♦ | 2 | 9 | 80 | 100 | mmu00071: fatty acid degradation, mmu00072: synthesis and degradation of ketone bodies, mmu00280: valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation, mmu00310: lysine degradation, mmu00380: tryptophan metabolism, mmu00620: pyruvate metabolism, mmu00630: glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism, mmu00640: propanoate metabolism, mmu00650: butanoate metabolism, mmu00900: terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, mmu01100: metabolic pathways, mmu01130: biosynthesis of antibiotics, mmu01200: carbon metabolism, mmu01212: fatty acid metabolism |

| acylglycerol kinase (Agk, Q9ESW4) ♦ | 2 | 9 | 89 | 100 | mmu00561: glycerolipid metabolism, mmu01100: metabolic pathways |

| acylphosphatase 1, erythrocyte (common) type (Acyp1, P56376) ♦ | 1 | 14 | 69 | 100 | mmu00620: pyruvate metabolism |

| adaptor-related protein complex 3, mu 1 subunit (Ap3m1, Q9JKC8) | 2 | 8 | 99 | 99 | mmu04142: lysosome |

| adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide 1 receptor 1 (Adcyap1r1, Q6NXJ9) | 2 | 3 | 120 | 100 | mmu04024: cAMP signaling pathway, mmu04080: neuroactive ligand–receptor interaction, mmu04713: circadian entrainment, mmu04911: insulin secretion, mmu04924: renin secretion |

| Araf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (Araf, P04627) | 2 | 3 | 95 | 98 | mmu04012: ErbB signaling pathway, mmu04068: FoxO signaling pathway, mmu04270: vascular smooth muscle contraction, mmu04650: natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity, mmu04720: long-term potentiation, mmu04726: serotonergic synapse, mmu04730: long-term depression, mmu04810: regulation of actin cytoskeleton, mmu04910: insulin signaling pathway, mmu04914: progesterone-mediated oocyte maturation, mmu05034: alcoholism, mmu05160: hepatitis C, mmu05200: pathways in cancer, mmu05205: proteoglycans in cancer, mmu05210: colorectal cancer, mmu05211: renal cell carcinoma, mmu05212: pancreatic cancer, mmu05213: endometrial cancer, mmu05214: glioma, mmu05215: prostate cancer, mmu05218: melanoma, mmu05219: bladder cancer, mmu05220: chronic myeloid leukemia, mmu05221: acute myeloid leukemia, mmu05223: nonsmall cell lung cancer |

| asparagine synthetase (Asns, Q61024) ♦ | 2 | 4 | 89 | 100 | mmu00250: alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, mmu01100: metabolic pathways |

| ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial F0 complex, subunit F (Atp5j, P97450) | 2 | 27 | 102 | 100 | mmu00190: oxidative phosphorylation, mmu01100: metabolic pathways, mmu05010: Alzheimer’s disease, mmu05012: Parkinson’s disease, mmu05016: huntington’s disease |

| CD81 antigen (Cd81, P35762) ♦ | 1 | 8 | 85 | 100 | mmu04662: B cell receptor signaling pathway, mmu05144: malaria, mmu05160: hepatitis C |

| cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha polypeptide 7 (Chrna7, P49582) | 1 | 4 | 67 | 100 | mmu04020: calcium signaling pathway, mmu04080: neuroactive ligand–receptor interaction, mmu04725: cholinergic synapse, mmu05033: nicotine addiction, mmu05204: chemical carcinogenesis |

| cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor 3 (Cpsf3, Q9QXK7) | 3 | 6 | 81 | 100 | mmu03015: mRNA surveillance pathway |

| exocyst complex component 2 (Exoc2, Q9D4H1) | 2 | 2 | 101 | 98 | mmu04014: Ras signaling pathway |

| G1 to S phase transition 2 (Gspt2, Q149F3) ♦ | 2 | 6 | 53 | 100 | mmu03015: mRNA surveillance pathway |

| gelsolin (Gsn, P13020) ♦ | 4 | 11 | 97 | 100 | mmu04666: Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis, mmu04810: regulation of actin cytoskeleton, mmu05203: viral carcinogenesis |

| golgi apparatus protein 1 (Glg1, Q61543) ♦ | 2 | 2 | 111 | 100 | mmu04514: cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) |

| HECT and RLD domain containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase family member 1 (Herc1, E9PZP8) | 2 | 0 | 80 | 98 | mmu04120: ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis |

| heme oxygenase 2 (Hmox2, O70252) ♦ | 4 | 19 | 150 | 100 | mmu00860: porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism, mmu04978: mineral absorption |

| insulin-degrading enzyme (Ide, Q9JHR7) | 3 | 3 | 110 | 98 | mmu05010: Alzheimer’s disease |

| kinesin family member 5A (Kif5a, P33175) | 8 | 8 | 445 | 95 | mmu04144: endocytosis, mmu04728: dopaminergic synapse |

| lamin A (Lmna, P48678) ♦ | 3 | 6 | 157 | 100 | mmu05410: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), mmu05412: arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), mmu05414: dilated cardiomyopathy |

| neurexin III (Nrxn3, Q6P9K9) | 2 | 2 | 88 | 98 | mmu04514: cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) |

| neuropilin 1 (Nrp1, P97333) ♦ | 1 | 2 | 67 | 100 | mmu04360: axon guidance, mmu05166: HTLV-I infection |

| neurotrophic tyrosine kinase, receptor, type 2 (Ntrk2, P15209) ♦ | 5 | 10 | 225 | 100 | mmu04010: MAPK signaling pathway, mmu04722: neurotrophin signaling pathway, mmu05034: alcoholism |

| nucleoporin 210 (Nup210, Q9QY81) | 1 | 1 | 53 | 96 | mmu03013: RNA transport |

| nucleoporin 62 (Nup62, Q63850) ♦ | 2 | 5 | 61 | 93 | mmu03013: RNA transport |

| prolactin regulatory element binding (Preb, Q9WUQ2) | 4 | 11 | 180 | 100 | mmu04141: protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum |

| proteasome (prosome, macropain) sub-unit, alpha type 7 (Psma7, Q9Z2U0) | 4 | 15 | 147 | 100 | mmu03050: proteasome |

| protein kinase C, delta (Prkcd, P28867) ♦ | 1 | 2 | 52 | 99 | mmu04062: chemokine signaling pathway, mmu04270: vascular smooth muscle contraction, mmu04530: tight junction, mmu04666: Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis, mmu04722: neurotrophin signaling pathway, mmu04750: inflammatory mediator regulation of TRP channels, mmu04912: GnRH signaling pathway, mmu04915: estrogen signaling pathway, mmu04930: type II diabetes mellitus, mmu04931: insulin resistance |

| protein kinase, AMP-activated, alpha 1 catalytic subunit (Prkaa1, Q5EG47) | 2 | 6 | 68 | 96 | mmu04068: FoxO signaling pathway, mmu04140: regulation of autophagy, mmu04150: mTOR signaling pathway, mmu04151: PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, mmu04152: AMPK signaling pathway, mmu04710: circadian rhythm, mmu04910: insulin signaling pathway, mmu04920: adipocytokine signaling pathway, mmu04921: oxytocin signaling pathway, mmu04922: glucagon signaling pathway, mmu04931: insulin resistance, mmu04932: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), mmu05410: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) |

| protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 3F (Ppp1r3f, Q9JIG4) | 2 | 5 | 77 | 99 | mmu04910: insulin signaling pathway |

| ribosomal protein S17 (Rps17, P63276) | 3 | 40 | 84 | 94 | mmu03010: ribosome |

| Sec24 related gene family, member D (S. cerevisiae) (Sec24d, Q6NXL1) | 2 | 3 | 98 | 100 | mmu04141: protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum |

| solute carrier family 32 (GABA vesicular transporter), member 1 (Slc32a1, O35633) ♦ | 1 | 2 | 71 | 100 | mmu04721: synaptic vesicle cycle, mmu04723: retrograde endocannabinoid signaling, mmu04727: GABAergic synapse, mmu05032: morphine addiction, mmu05033: nicotine addiction |

| squamous cell carcinoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (Sart1, Q9Z315) ♦ | 1 | 2 | 72 | 100 | mmu03040: spliceosome |

| synaptic Ras GTPase activating protein 1 homologue (rat) (Syngap1, F6SEU4) | 2 | 3 | 76 | 97 | mmu04014: Ras signaling pathway |

| talin 1 (Tln1, P26039) | 7 | 3 | 299 | 92 | mmu04015: Rap1 signaling pathway, mmu04510: focal adhesion, mmu04611:platelet activation, mmu05166: HTLV-I infection |

| ubiquitination factor E4A (Ube4a, E9Q735) ♦ | 2 | 3 | 95 | 100 | mmu04120: ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis |

| ubiquitination factor E4B (Ube4b, Q9ES00) ♦ | 1 | 2 | 52 | 98 | mmu04120: ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, mmu04141: protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum |

| voltage-dependent anion channel 2 (Vdac2, Q60930) | 2 | 8 | 107 | 100 | mmu04020: calcium signaling pathway, mmu04022: cGMP-PKG signaling pathway, mmu05012: Parkinson’s disease, mmu05016: Huntington’s disease, mmu05166: HTLV-I infection |

| WAS protein family, member 3 (Wasf3, Q8VHI6) | 1 | 4 | 95 | 100 | mmu04520: adherens junction, mmu04666: Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis, mmu05231: choline metabolism in cancer |

| zyxin (Zyx, Q62523) ♦ | 1 | 3 | 66 | 100 | mmu04510: focal adhesion |

42 of the 121 total interacting proteins were characterized with KEGG pathway terms using DAVID. Proteins are identified by protein name, and gene name, accession numbers. The number of unique peptides, sequence coverage (seq. cov. %), ion scores, and probability (prob. score %) for each protein is provided. High-salt wash-eluted proteins are identified with “♦.”.

Table 3.

Selection of Identified α7-nAChR Interacting Proteins Associated with Human Diseasea

| protein name (gene name, accession number) | unique Peptides | seq cov. (%) | ion score | prob. Score (%) | AD | IR | PD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase catalytic subunit alpha-1 (Prkaa1, Q5EG47) | 2 | 6 | 68 | 96 | 47 | 67 | 81 |

| acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, cytosolic (Acat2, Q8CAY6) ♦ | 2 | 9 | 80 | 100 | - | 62 | 91 |

| ATP synthase-coupling factor 6, mitochondrial (Atp5j, P97450) | 2 | 27 | 102 | 100 | 92 | - | - |

| BDNF/NT-3 growth factors receptor (Ntrk2, P15209) ♦ | 5 | 10 | 225 | 100 | - | - | 80 |

| chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 5 (Cspg5, Q71M36) | 1 | 2 | 68 | 98 | 93 | - | - |

| CUB and sushi domain-containing protein 1 (Csmd1, Q923L3) | 3 | 1 | 98 | 99 | 94 | - | - |

| disks large-associated protein 3 (Dlgap3, Q6PFD5) ♦ | 1 | 2 | 53 | 99 | - | - | 75 |

| endosomal/lysomomal potassium channel TMEM175 (Tmem175, Q9CXY1) ♦ | 1 | 4 | 58 | 100 | - | - | 95 |

| exocyst complex component 2 (Exoc2, Q9D4H1) | 2 | 2 | 101 | 98 | 96 | - | - |

| gelsolin (Gsn, P13020) ♦ | 4 | 11 | 97 | 100 | 97 | - | - |

| glia maturation factor β (Gmfb, Q9CQI3) ♦ | 2 | 24 | 112 | 100 | - | - | 98 |

| heme oxygenase 2 (Hmox2, O70252) ♦ | 4 | 19 | 150 | 100 | - | - | 79 |

| hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1 (Hapln1, Q9QUP5) | 2 | 8 | 94 | 98 | 99 | - | - |

| insulin-degrading enzyme (Ide, Q9JHR7) | 3 | 3 | 110 | 98 | 100 | 57 | 82 |

| leucine-rich repeat neuronal protein 1 (Lingo1, Q9D1T0) ♦ | 3 | 7 | 113 | 99 | - | - | 78 |

| MAP/microtubule affnity-regulating kinase 2 (Mark2, Q05512) | 6 | 11 | 177 | 100 | 49,50 | - | 101 |

| MAP/microtubule affnity-regulating kinase 4 (Mark4, Q8CIP4) ♦ | 3 | 6 | 91 | 96 | 49 | - | - |

| neuronal acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha-7 (Chrna7, P49582) | 1 | 4 | 67 | 100 | 16,17,41,84 | 102 | 43,103 |

| neuropilin-1 (Nrp1, P97333) ♦ | 1 | 2 | 67 | 100 | 104 | 58 | - |

| nucleobindin-1 (Nucb1, Q02819) ♦ | 5 | 13 | 172 | 100 | 53 | - | - |

| oxysterol-binding protein 1 (Osbp, Q3B7Z2) ♦ | 1 | 4 | 81 | 100 | 105 | - | - |

| potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily A member 3 (Kcna3,P16390) | 5 | 11 | 266 | 100 | 55,106 | 59,60 | - |

| prelamin-A/C (Lmna, P48678) ♦ | 3 | 6 | 157 | 100 | - | 64 | - |

| protein kinase C δ type (Prkcd, P28867) ♦ | 1 | 2 | 52 | 99 | 51 | 65,66 | - |

| Ras/Rap GTPase-activating protein SynGAP (Syngap1, F6SEU4) | 2 | 3 | 76 | 97 | 105 | - | - |

| regulator of G-protein signaling 6 (Rgs6, Q9Z2H2) | 3 | 10 | 159 | 100 | 56 | - | - |

| Sec24 related gene family, member D (Sec24d, Q6NXL1) | 2 | 3 | 98 | 100 | - | - | 107,108 |

| target of Myb protein 1 (Tom1, O88746) | 2 | 5 | 83 | 95 | 109 | - | - |

| utrophin (Utrn, E9Q6R7) | 3 | 1 | 139 | 100 | 110,111 | 112 | 113 |

| voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 2 (Vdac2, Q60930) | 2 | 8 | 107 | 100 | 114 | - | - |

| zyxin (Zyx, Q62523) ♦ | 1 | 3 | 66 | 100 | 115 | - | - |

Proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), insulin resistance (IR), and/or Parkinson’s disease (PD). These interactions are related to these pathologies either directly by the protein or through genetic association. Proteins are identified by protein name, gene name, and accession numbers. The number of unique peptides, sequence coverage (seq. cov. %), ion scores, probability (prob. score %), and the associated disease are all indicated. High-salt-wash-eluted proteins are identified with “♦.” AD, IR, and PD columns provide references for examples of associations of each protein with the specified disease state.

Several of these identified proteins are related to Alzheimer’s disease, which is a progressive form of dementia pathologically characterized by extracellular plaques containing β-amyloid (Aβ) and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles containing hyperphosphorylated tau proteins.38,39 Alzheimer’s disease is also characterized by loss of cholinergic neurons, resulting in a reduction of nAChR protein expression. Numerous studies have investigated the connection between α7-nAChRs and Alzheimer’s disease.40,41 Activation of α7-nAChRs reduces neuroinflammation and is considered neuroprotective against Alzheimer’s disease related toxicities (e.g., Aβ1–42 toxicity).42–44 These observations have led to the pursuit of cholinergic therapeutics for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.45,46 Proteins associated with both Aβ and hyper-phosphorylation of tau proteins, the two major components of Alzheimer’s disease pathology, were identified in the α7-nAChR interactome (Table 2, Table 3).

One of the molecular function enrichments identified during STRING analysis was tau-protein kinase activity (GO: 005021, FDR 0.02) (Figure 6, Figure 7). The phosphorylation of tau by multiple proteins is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease pathology and therefore of interest for the study of Alzheimer’s disease. The three interactors identified were 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase catalytic subunit alpha-1 (Prkaa1), MAP/ microtubule affnity-regulating kinase 2 (MARK2), and MAP/microtubule affnity-regulating kinase 4 (MARK4). Prkaa1 is one of the subunits of 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). AMPK has been shown to phosphorylate tau proteins in response to Aβ.47 Two AMPK-related proteins, MARK2 and MARK4, were also identified.48 As with AMPK, both MARK2 and MARK4 have been shown to phosphorylate tau proteins.49 It has also been shown by several groups that MARK2 is phosphorylated by glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), a principle tau kinase, inactivating MARK2.50 We reviewed the literature to identify additional AD related proteins that may not be represented in STRING (Table 3). Identified proteins, such as insulin-degrading enzyme, that are associated with Alzheimer’s disease but not highlighted by STRING analysis may affect the following: (1) interaction with APP or Aβ;51–54 (2) altered expression or function in Alzheimer’s disease;55 (3) or have a genetic association.56

The α7-nAChR interactome reported in this study also includes proteins associated with insulin sensitivity or resistance,57–62 with changes in gene or protein expression,63 with genetic links to diabetes,64 with alteration of biological processes central to diabetes,65,66 or with the effects of smoking behavior on diabetes (Table 3).67 STRING analysis of α7-nAChR interacting proteins identified carbohydrate derivative binding as an enriched molecular function (GO: 0097367, FDR 0.02) (Figure 6, Figure 7). The identification of proteins associated with both insulin resistance and Alzheimer’s disease is particularly interesting as shared similarities exist in some of the abnormal carbohydrate derivative sensitivity (e.g., to D-glucose) and metabolic pathways involved in both of these medically relevant conditions.68–71 For example, individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (i.e., insulin resistance) are more susceptible to an increased risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease.72–74

As with Alzheimer’s disease, neuroprotection mediated by α7-nAChR activation has been demonstrated in several models of Parkinson’s disease (PD).75 Stimulation of α7-nAChRs can also ameliorate dyskinesia in models of Parkinson’s disease.76,77 Several proteins in the α7-nAChR interactome reported in this study are genetically associated with certain populations of patients with Parkinson’s disease (Table 3).78,79 Additionally certain proteins in the α7-nAChR interactome have altered expression levels in PD patients, such as ATP5J, a component of a mitochondrial ATP synthase (Table 2, Table 3).80 Additional proteins identified in this study are associated with neuroprotection against α-synuclein toxicity in Parkinson’s disease or are activated by α-synuclein.81,82 Overall, α7-nAChR function may be involved in the molecular dysfunction of multiple diseases and the α7-nAChR interactome may therefore be of interest as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of those diseases. Identification of the protein–protein interactions of α7-nAChRs may help us understand how the receptor-protein interactions with these ion channels may be involved with human disease and may lead to the development of novel therapeutics.

A connection between α7-nAChRs and Alzheimer’s disease from human post-mortem studies is undeniable, but the details of the association still need to be clarified. The findings presented in this study may be used as a foundation for the study α7-nAChRs using animal models of human disease, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) rodent models.

An investigation of α7 KO mice crossed with an amyloid precursor protein (APP) overexpressing mouse line (“APPα7-KO”) demonstrated that APPα7KO mice demonstrated the same levels of APP and Aβ as control APP mice, but did not suffer cognitive defects of the same magnitude.83 It has been shown that extracellular Aβ binds α7-nAChRs and enhances the internalization of the receptors.17,84 This could increase Aβ intracellularly, leading to increased toxicity and possibly cell death. This hypothesis would support the fact that while α7 KO mice demonstrate the same levels of APP and Aβ as wild-type mice, deletion of α7-nAChRs can reduce Aβ internalization and therefore reduce toxicity resulting in reduced cognitive loss. Thus, prevention of α7-nAChR internalization caused by Aβ may be a therapeutic target for the alleviation of cognitive decline in AD, not necessarily through the prevention of Aβ aggregation, but rather through amelioration of Aβ toxicity.

Fifty-five murine α7-nAChR interacting proteins have been previously reported by Paulo et al., 2009, using α-bgtx-affnity protein isolation and mass spectrometry. Comparing the 55 proteins from this previous study to our present findings: a single protein, gelsolin, was identified in both; 6 were not identified in the present study; and the remaining 48 were identified in the α7 KO control samples in the present study and therefore were not included as α7-nAChR interacting proteins. There were several changes in experimental methods that may account for the differences in the proteins identified in this study compared with the previous study. These methodological changes were made to increase α7-nAChR isolation effciency to address a concern expressed by Paulo et al., 2009, that while immunoblots identified the α7 subunit in the carbachol elution from the α-bgtx affnity beads, the subunit was not identified using mass spectrometry, despite the identification of α7-nAChR interacting proteins.

The general workflow described in the present study is similar to the previous study, with changes in experimental methods to increase the effciency of α7-nAChR isolation, including changes in α-bgtx levels conjugated to beads (four times the amount used in the previous study), in homogenization buffer selection, in trypsin digest (in-gel vs in-solution), and in the sensitivity of available mass spectrometry technology. These alterations were made specifically to enable the identification of α7-nAChR peptides in α-bgtx-affnity enriched samples after analysis using mass spectrometry. Using a protocol similar to Paulo et al., 2009, 1.5 ± 0.4 fmol 125I-α-bgtx/mg protein was observed. After our modifications, and as shown in Figure 3, we were able to isolate >5 fmol 125I-α-bgtx/mg protein. In addition to procedural changes, the Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer used in the present study is more sensitive than the LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer used in the previous study. These methodological changes may have increased our ability to detect proteins as well as the nonspecific interactions with α-bgtx-affnity beads. These qualities, while advantageous for detecting α7-nAChRs, would also affect proteins in control samples, identifying proteins in both that were not detected using the methods in the previous study. The changes made to our workflow for our present study did result in the identification of α7-nAChR subunit peptide by mass spectrometry.

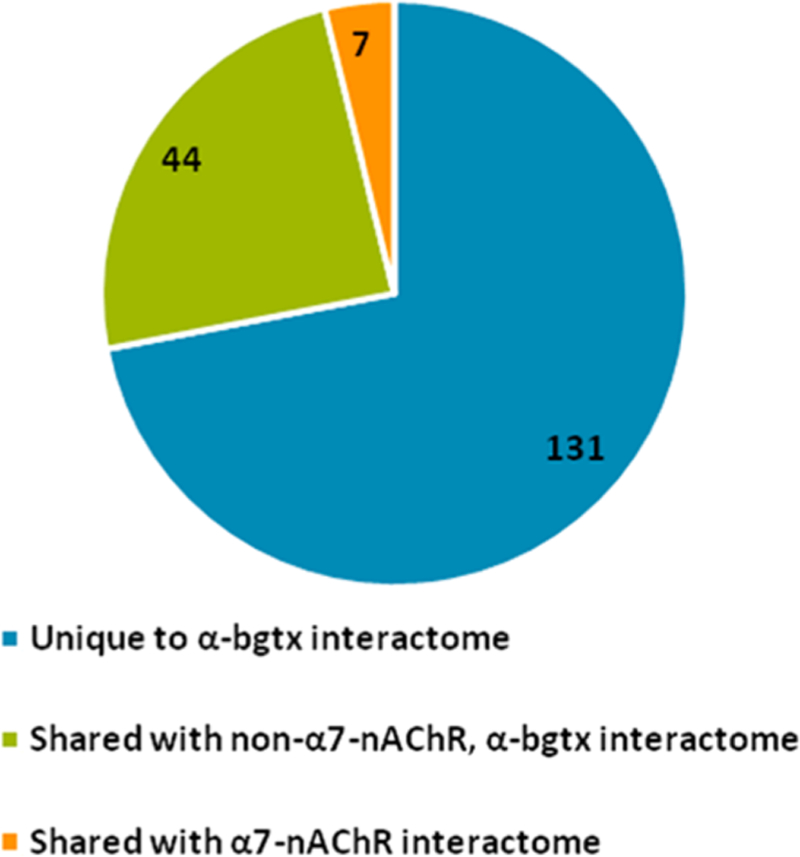

α-Bungarotoxin Interacting Proteins

In addition to the murine α7-nAChR interactome, we also investigated proteins interacting with α-bgtx. To derive meaningful proteomic data from α-bgtx affnity-immobilization, appropriate controls must be utilized to identify nonspecific interactions that should be excluded from the analysis of the α7-nAChR interactome. In total, 183 proteins were identified in the α-bgtx interactome. Of the total of 183 proteins, 7 (4% of the total α-bgtx interactome) proteins were identified in both the carbachol-eluted α-bgtx and α7-nAChR interactomes. In contrast, 44 (24% of the total α-bgtx interactome) proteins were identified in both the α-bgtx interactome and the non-α7-nAChR, α-bgtx interactome (Figure 8). The large number of proteins that are shared between the two α-bgtx interactomes, regardless of α7-nAChR expression, demonstrates the importance of using appropriate controls. The α-bgtx interactome was identified in C57Bl/6, whereas the α7-nAChR and non-α7-nAChR, α-bgtx interactomes were identified in FVB. While strain differences may contribute to reduced levels of overlap between interactomes, the 24% of interacting proteins that are still identified between the α-bgtx and non-α7-nAChR, α-bgtx interactomes is diffcult to ignore. The distinction between α-bgtx-selective and α7-nAChR-selective controls is also important as other proteins have recently been reported to bind to α-bgtx in mammalian brain tissue, most notably several GABAAR subtypes.21,35

Figure 8.

Comparison of the carbachol eluted proteins from the three identified interactomes. The number of α-bgtx interacting proteins identified in the α7-nAChR interactome or the non-α7-nAChR, α-bgtx interactome. No proteins were identified in both the α7-nAChR and non-α7-nAChR, α-bgtx interactomes.

Proteins isolated on α-bgtx-affnity and control beads from α7-nAChR KO samples were compared to identify proteins that interacted with α-bgtx in the absence of α7-nAChR expression. We identified a total of 369 proteins interacting with α-bgtx in the absence of α7-nAChR (192 high-salt wash-eluted, 232 carbachol-eluted, 55 shared in both elutions) (Figure 4B, Supplemental Tables S-7). These proteins can therefore be considered as possible non-α7-nAChR specific “contaminants” for studies using α-bgtx-affnity to investigate α7-nAChR-protein interactions. Our data show that the β1 GABAAR subunit was identified in elutions from α-bgtx beads in α7 KO samples (Table 1D). This finding was consistent with the identification of the β3 GABAAR subunit from α-bgtx-affnity bead versus control bead comparisons in WT mice (Supplemental Tables S-8). Both β1 and β3 subunits have been associated with GABAARs with affnity for α-bgtx.21,35 Moreover, GABAAR peptides were absent in α7-nAChR interactomes. The comparison of carbachol-eluted proteins from α-bgtx-affnity beads to proteins eluted from control beads identifies proteins by α-bgtx-affnity rather than α7-nAChR specificity. Interestingly, the non-α7-nAChR, α-bgtx-interactome had large overlap (13%) between the high-salt wash elutions and carbachol elution fractions compared to the identified α7-nAChR interactome (1% overlap) or α-bgtx interactome (1%).

Two different mouse strains were used in this study. C57Bl/ 6J (“C57Bl/6”) mice, the same mouse strain used in our previous investigations, were used to identify the α-bgtx interactome.20 FVB/NJ (“FVB”) mice were used in our investigation of the α7-nAChR interactome and the non-α7-nAChR, α-bgtx interactome, due to the availability of the α7 KO genotype in this strain. With the advantage of large litter sizes and zygote pronuclei, FVB are often used in transgenic studies.85 As is common when comparing any two mouse strains, genetic differences exist between C57 and FVB mice.86These differences could lead to deviations in protein levels and the composition of nAChR interacting proteins, although no cross-strain comparisons were performed. Several reports suggest that in general, α7 KO mice do not present significant changes in physical, neurological, or behavioral phenotype compared to wild-type mice; however, several distinct phenotypes have been reported in α7 KO mice.87–89 Depression-like phenotypes mediated through BDNF-TRKB signaling have been shown in α7 KO mice.90 Neuronal TRKB (ntrk2) was identified in this study, suggesting that depression-like phenotypes in knockout mice may be caused by the lack of interaction between ntrk2 and the α7-nAChR.

CONCLUSIONS

Here we compared the α-bgtx-affnity proteins from both α7-nAChR wild-type and KO mouse whole brain tissue to identify both affnity purified α7-nAChR as well as novel interacting proteins. This investigation also characterized two additional murine interactomes: a total α-bgtx interactome and a non-α7-nAChR, α-bgtx interactome. The data presented here expanded upon our previous investigations of α7-nAChR interacting proteins using α-bgtx-affnity bead isolation, differentiating between α7-nAChR- and α-bgtx-specific negative controls, and using the latest mass spectrometry technology.

Including the α7-nAChR subunit, 121 α7-nAChR interacting proteins were identified in this study. These interacting proteins were identified in two fractions: a high-salt wash eluted- and a carbachol-eluted fraction from the same α-bgtx-affnity immobilized samples. Additionally, the two α-bgtx interactomes identified in this work were novel and highlight proteins that should be viewed cautiously if using α-bgtx for affnity proteomics when an α7-nAChR-specific control is not available.

Using α-bgtx to affnity-immobilize α7-nAChRs provides an alternative to immunoprecipitation for isolating α7-nAChRs and its interacting proteins. Many groups have reported inconsistencies when using certain nicotinic receptor-specific antibodies, such as detecting immunoreactivity in nAChR null models.32,33 Based on these observations, using antibodies for nAChR affnity proteomics may lead to inaccurate findings. As such, α-bgtx may be advantageous because of its well-characterized affnity for both human and murine α7-nAChRs.

Affnity purification of α7-nAChRs with α-bgtx is not without diffculties. The toxin’s high affnity may prove problematic; thus, elution conditions must be more stringent than those needed with antibody methodologies. The issue of selectivity has also been raised with several GABAAR subtypes shown to have α-bgtx-affnity. This concern was alleviated by using appropriately selected α7-nAChR-specific control groups. We demonstrated that beads without conjugated ligand were not suffcient to achieve α7-nAChR specificity in α-bgtx-affnity proteomics. This point was highlighted by the identification of GABAAR peptides in both α-bgtx inter-actomes, whereas GABAAR peptides were not identified in the α7-nAChR-specific interactome.

The strategies and data described in this work highlight improvements in methodologies for isolating the α7-nAChR and associated protein complexes from the murine whole brain. The positive identification in this study of the α7-nAChR subunit, and its associated receptor interactome, established a foundation for the investigation of α7-nAChR interacting proteins in murine models of human disease. These investigations open new possibilities for investigating proteomic alterations in α7-nAChR interacting proteins caused by or contributing to specific disease states.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work presented here was performed in part to fulfill requirements for a Ph.D. degree (M.J.M.). This research is based in part upon work conducted using the Rhode Island NSF/EPSCoR Proteomics Share Resource Facility, which is supported in part by the National Science Foundation EPSCoR Grant No. 1004057, National Institutes of Health Grant No. 1S10RR020923, S10RR027027, a Rhode Island Science and Technology Advisory Council grant, and the Division of Biology and Medicine, Brown University. We thank Dr. James Clifton for his technical assistance in mass spectrometry sample preparation and analysis. We also thank Dr. Steven P Gygi and the Taplin Mass Spectrometry Facility at Harvard Medical School for use of their mass spectrometers.

Funding

This research was supported by NIH 1R21AG038774 (E.H.), NIH 1S10RR027027 (E.H.), NSF EPS-1004057 (E.H. and M.J.M.), and NIH K01DK098285 (J.A.P.)

ABBREVIATIONS

- α-bgtx

α-bungarotoxin

- α7 KO

α7-nAChR knockout

- BCA

bicinchoninic acid

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- LGIC

ligand gated ion channel

- MLA

methyllycaconitine

- nAChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00618.

REFERENCES

- (1).Dani JA; Bertrand D Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms of the central nervous system. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 2007, 47 (1), 699–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Barry PH; Lynch JW Ligand-gated channels. IEEE transactions on nanobioscience 2005, 4 (1), 70–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Millar NS; Gotti C Diversity of vertebrate nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology 2009, 56 (1), 237–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Mulcahy MJ; Lester HA Granulocytes as models for human protein marker identification following nicotine exposure. J. Neurochem 2017, 142 (S2), 151–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Albuquerque EX; Pereira EF; Alkondon M; Rogers SW Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol. Rev 2009, 89 (1), 73–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Uteshev VV α7 nicotinic ACh receptors as a ligand-gated source of Ca2+ ions: the search for a Ca2+ optimum. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2012, 740, 603–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Marks MJ; Collins AC Characterization of nicotine binding in mouse brain and comparison with the binding of α-bungarotoxin and quinuclidinyl benzilate. Mol. Pharmacol 1982, 22 (3), 554–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Whiteaker P; Davies AR; Marks MJ; Blagbrough IS; Potter BV; Wolstenholme AJ; Collins AC; Wonnacott S An autoradiographic study of the distribution of binding sites for the novel α7-selective nicotinic radioligand [3H]-methyllycaconitine in the mouse brain. European journal of neuroscience 1999, 11 (8), 2689–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Falkeborn Y; Larsson C; Nordberg A; Slanina P A comparison of the regional ontogenesis of nicotine- and muscarine-like binding sites in mouse brain. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci 1983, 1 (4–5), 289–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Court JA; Lloyd S; Johnson M; Griffiths M; Birdsall NJ; Piggott MA; Oakley AE; Ince PG; Perry EK; Perry RH Nicotinic and muscarinic cholinergic receptor binding in the human hippocampal formation during development and aging. Dev. Brain Res 1997, 101 (1–2), 93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Marks MJ; Pauly JR; Grun EU; Collins AC ST/b and DBA/2 mice differ in brain alpha-bungarotoxin binding and α7 nicotinic receptor subunit mRNA levels: a quantitative autoradio-graphic analysis. Mol. Brain Res 1996, 39 (1–2), 207–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Wang Y; Yao Y; Tang XQ; Wang ZZ Mouse RIC-3, an endoplasmic reticulum chaperone, promotes assembly of the α7 acetylcholine receptor through a cytoplasmic coiled-coil domain. J. Neurosci 2009, 29 (40), 12625–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Valles AS; Barrantes FJ Chaperoning α7 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr 2012, 1818 (3), 718–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).St John PA Cellular trafficking of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Acta Pharmacol. Sin 2009, 30 (6), 656–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Shaw S; Bencherif M; Marrero MB Janus kinase 2, an early target of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated neuro-protection against Aβ-(1–42) amyloid. J. Biol. Chem 2002, 277 (47), 44920–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Tong M; Arora K; White MM; Nichols RA Role of key aromatic residues in the ligand-binding domain of α7 nicotinic receptors in the agonist action of β-amyloid. J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286 (39), 34373–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wang HY; Lee DH; D’Andrea MR; Peterson PA; Shank RP; Reitz AB β-Amyloid(1–42) binds to α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with high affinity. Implications for Alzheimer’s disease pathology. J. Biol. Chem 2000, 275 (8), 5626–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Huttlin EL; Bruckner RJ; Paulo JA; Cannon JR; Ting L; Baltier K; Colby G; Gebreab F; Gygi MP; Parzen H; Szpyt J; Tam S; Zarraga G; Pontano-Vaites L; Swarup S; White AE; Schweppe DK; Rad R; Erickson BK; Obar RA; Guruharsha KG; Li K; Artavanis-Tsakonas S; Gygi SP; Harper JW Architecture of the human interactome defines protein communities and disease networks. Nature 2017, 545 (7655), 505–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Huttlin EL; Ting L; Bruckner RJ; Gebreab F; Gygi MP; Szpyt J; Tam S; Zarraga G; Colby G; Baltier K; Dong R; Guarani V; Vaites LP; Ordureau A; Rad R; Erickson BK; Wuhr M; Chick J; Zhai B; Kolippakkam D; Mintseris J; Obar RA; Harris T; Artavanis-Tsakonas S; Sowa ME; De Camilli P; Paulo JA; Harper JW; Gygi SP The BioPlex Network: A Systematic Exploration of the Human Interactome. Cell 2015, 162 (2), 425–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Paulo JA; Brucker WJ; Hawrot E Proteomic analysis of an α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor interactome. J. Proteome Res 2009, 8 (4), 1849–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Hannan S; Mortensen M; Smart TG Snake neurotoxin α-bungarotoxin is an antagonist at native GABA receptors. Neuropharmacology 2015, 93, 28–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Simonson PD; Deberg HA; Ge P; Alexander JK; Jeyifous O; Green WN; Selvin PR Counting bungarotoxin binding sites of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mammalian cells with high signal/noise ratios. Biophys. J 2010, 99 (10), L81–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kessner D; Chambers M; Burke R; Agus D; Mallick P ProteoWizard: open source software for rapid proteomics tools development. Bioinformatics 2008, 24 (21), 2534–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Keller A; Nesvizhskii A; Kolker E; Aebersold R Empirical Statistical Model To Estimate the Accuracy of Peptide Identifications Made by MS/MS and Database Search. Anal. Chem 2002, 74, 5383–5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Nesvizhskii AI; Keller A; Kolker E; Aebersold R A statistical model for identifying proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem 2003, 75 (17), 4646–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Weatherly DB; Atwood JA 3rd; Minning TA; Cavola C; Tarleton RL; Orlando R A Heuristic method for assigning a false-discovery rate for protein identifications from Mascot database search results. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2005, 4 (6), 762–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Huang DW; Sherman BT; Lempicki RA Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc 2009, 4 (1), 44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Szklarczyk D; Franceschini A; Wyder S; Forslund K; Heller D; Huerta-Cepas J; Simonovic M; Roth A; Santos A; Tsafou KP; Kuhn M; Bork P; Jensen LJ; von Mering C STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43 (D1), D447–D452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Lukas RJ; Norman SA; Lucero L Characterization of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Expressed by Cells of the SH-SY5Y Human Neuroblastoma Clonal Line. Mol. Cell. Neurosci 1993, 4 (1), 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Nordman JC; Kabbani N An interaction between α7 nicotinic receptors and a G-protein pathway complex regulates neurite growth in neural cells. J. Cell Sci 2012, 125 (22), 5502–5513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Gomez-Varela D; Schmidt M; Schoellerman J; Peters EC; Berg DK PMCA2 via PSD-95 controls calcium signaling by α7-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on aspiny interneurons. J. Neurosci 2012, 32 (20), 6894–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Moser N; Mechawar N; Jones I; Gochberg-Sarver A; Orr-Urtreger A; Plomann M; Salas R; Molles B; Marubio L; Roth U; Maskos U; Winzer-Serhan U; Bourgeois JP; Le Sourd AM; De Biasi M; Schroder H; Lindstrom J; Maelicke A; Changeux JP; Wevers A Evaluating the suitability of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antibodies for standard immunodetection procedures. J. Neuro-chem 2007, 102 (2), 479–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Herber DL; Severance EG; Cuevas J; Morgan D; Gordon MN Biochemical and histochemical evidence of non-specific binding of α7nAChR antibodies to mouse brain tissue. J. Histochem. Cytochem 2004, 52 (10), 1367–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Mulcahy MJ; Blattman SB; Barrantes FJ; Lukas RJ; Hawrot E Resistance to Inhibitors of Cholinesterase 3 (Ric-3) Expression Promotes Selective Protein Associations with the Human α7-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Interactome. PLoS One 2015, 10 (8), e0134409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).McCann CM; Bracamontes J; Steinbach JH; Sanes JR The cholinergic antagonist alpha-bungarotoxin also binds and blocks a subset of GABA receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2006, 103 (13), 5149–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Uspenska K; Lykhmus O; Obolenskaya M; Pons S; Maskos U; Komisarenko S; Skok M Mitochondrial Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Support Liver Cells Viability After Partial Hepatectomy. Front. Pharmacol 2018, 9, 626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).King JR; Kabbani N α7 nicotinic receptors attenuate neurite development through calcium activation of calpain at the growth cone. PLoS One 2018, 13 (5), e0197247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Price JL; Davis PB; Morris JC; White DL The distribution of tangles, plaques and related immunohistochemical markers in healthy aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 1991, 12 (4), 295–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Braak H; Braak E Staging of Alzheimer’s disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiol. Aging 1995, 16 (3), 271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Wevers A; Burghaus L; Moser N; Witter B; Steinlein OK; Schutz U; Achnitz B; Krempel U; Nowacki S; Pilz K; Stoodt J; Lindstrom J; De Vos RA; Jansen Steur E. N.; Schroder H Expression of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: postmortem investigations and experimental approaches. Behav. Brain Res 2000, 113 (1–2), 207–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Hellstrom-Lindahl E; Mousavi M; Zhang X; Ravid R; Nordberg A Regional distribution of nicotinic receptor subunit mRNAs in human brain: comparison between Alzheimer and normal brain. Mol. Brain Res 1999, 66 (1–2), 94–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Jin Y; Tsuchiya A; Kanno T; Nishizaki T Amyloid-β peptide increases cell surface localization of α7 ACh receptor to protect neurons from amyloid β-induced damage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2015, 468 (1–2), 157–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Foucault-Fruchard L; Antier D Therapeutic potential of α7 nicotinic receptor agonists to regulate neuroinflammation in neuro-degenerative diseases. Neural Regener. Res 2017, 12 (9), 1418–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Akaike A; Takada-Takatori Y; Kume T; Izumi Y Mechanisms of neuroprotective effects of nicotine and acetylcholi-nesterase inhibitors: role of α4 and α7 receptors in neuroprotection. J. Mol. Neurosci 2010, 40 (1–2), 211–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Dineley KT; Pandya AA; Yakel JL Nicotinic ACh receptors as therapeutic targets in CNS disorders. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 2015, 36 (2), 96–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Xia M; Cheng X; Yi R; Gao D; Xiong J The Binding Receptors of Aβ: an Alternative Therapeutic Target for Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol 2016, 53 (1), 455–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Thornton C; Bright NJ; Sastre M; Muckett PJ; Carling D AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a tau kinase, activated in response to amyloid beta-peptide exposure. Biochem. J 2011, 434 (3), 503–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Bright NJ; Thornton C; Carling D The regulation and function of mammalian AMPK-related kinases. Acta Physiol 2009, 196 (1), 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Gu GJ; Lund H; Wu D; Blokzijl A; Classon C; von Euler G; Landegren U; Sunnemark D; Kamali-Moghaddam M Role of individual MARK isoforms in phosphorylation of tau at Ser(2)(6)(2) in Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroMol. Med 2013, 15 (3), 458–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Timm T; Balusamy K; Li X; Biernat J; Mandelkow E; Mandelkow EM Glycogen synthase kinase (GSK) 3beta directly phosphorylates Serine 212 in the regulatory loop and inhibits microtubule affinity-regulating kinase (MARK) 2. J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283 (27), 18873–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Nakai M; Tanimukai S; Yagi K; Saito N; Taniguchi T; Terashima A; Kawamata T; Yamamoto H; Fukunaga K; Miyamoto E; Tanaka C Amyloid β protein activates PKC-δ and induces translocation of myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS) in microglia. Neurochem. Int 2001, 38 (7), 593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Zerbinatti CV; Cordy JM; Chen CD; Guillily M; Suon S; Ray WJ; Seabrook GR; Abraham CR; Wolozin B Oxysterol-binding protein-1 (OSBP1) modulates processing and trafficking of the amyloid precursor protein. Mol. Neurodegener 2008, 3, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Bonito-Oliva A; Barbash S; Sakmar TP; Graham WV Nucleobindin 1 binds to multiple types of pre-fibrillar amyloid and inhibits fibrillization. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 42880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Codocedo JF; Montecinos-Oliva C; Inestrosa NC Wnt-related SynGAP1 is a neuroprotective factor of glutamatergic synapses against Aβ oligomers. Front. Cell. Neurosci 2015, 9, 227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Lowinus T; Bose T; Busse S; Busse M; Reinhold D; Schraven B; Bommhardt UH Immunomodulation by memantine in therapy of Alzheimer’s disease is mediated through inhibition of Kv1.3 channels and T cell responsiveness. Oncotarget 2016, 7 (33), 53797–53807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Moon SW; Dinov ID; Kim J; Zamanyan A; Hobel S; Thompson PM; Toga AW Structural Neuroimaging Genetics Interactions in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis 2015, 48 (4), 1051–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Tang WJ Targeting Insulin-Degrading Enzyme to Treat Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Trends Endocrinol. Metab 2016, 27 (1), 24–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Dai X; Okon I; Liu Z; Bedarida T; Wang Q; Ramprasath T; Zhang M; Song P; Zou MH Ablation of Neuropilin 1 in Myeloid Cells Exacerbates High-Fat Diet-Induced Insulin Resistance Through Nlrp3 Inflammasome In Vivo. Diabetes 2017, 66 (9), 2424–2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Tschritter O; Machicao F; Stefan N; Schafer S; Weigert C; Staiger H; Spieth C; Haring HU; Fritsche A A new variant in the human Kv1.3 gene is associated with low insulin sensitivity and impaired glucose tolerance. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 2006, 91 (2), 654–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Xu J; Wang P; Li Y; Li G; Kaczmarek LK; Wu Y; Koni PA; Flavell RA; Desir GV The voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3 regulates peripheral insulin sensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2004, 101 (9), 3112–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Bezy O; Tran TT; Pihlajamaki J; Suzuki R; Emanuelli B; Winnay J; Mori MA; Haas J; Biddinger SB; Leitges M; Goldfine AB; Patti ME; King GL; Kahn CR PKCδ regulates hepatic insulin sensitivity and hepatosteatosis in mice and humans. J. Clin. Invest 2011, 121 (6), 2504–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Wang YJ; Bian Y; Luo J; Lu M; Xiong Y; Guo SY; Yin HY; Lin X; Li Q; Chang CCY; Chang TY; Li BL; Song BL Cholesterol and fatty acids regulate cysteine ubiquitylation of ACAT2 through competitive oxidation. Nat. Cell Biol 2017, 19 (7), 808–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Khamaisi M; Katagiri S; Keenan H; Park K; Maeda Y; Li Q; Qi W; Thomou T; Eschuk D; Tellechea A; Veves A; Huang C; Orgill DP; Wagers A; King GL PKCδ inhibition normalizes the wound-healing capacity of diabetic human fibroblasts. J. Clin. Invest 2016, 126 (3), 837–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Florwick A; Dharmaraj T; Jurgens J; Valle D; Wilson KL LMNA Sequences of 60,706 Unrelated Individuals Reveal 132 Novel Missense Variants in A-Type Lamins and Suggest a Link between Variant p.G602S and Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Genet 2017, 8, 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Yamamoto K; Mizuguchi H; Tokashiki N; Kobayashi M; Tamaki M; Sato Y; Fukui H; Yamauchi A Protein kinase C-δ signaling regulates glucagon secretion from pancreatic islets. journal of medical investigation: JMI 2017, 64 (1.2), 122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Frangioudakis G; Burchfield JG; Narasimhan S; Cooney GJ; Leitges M; Biden TJ; Schmitz-Peiffer C Diverse roles for protein kinase C δ and protein kinase C ε in the generation of high-fat-diet-induced glucose intolerance in mice: regulation of lipogenesis by protein kinase C δ. Diabetologia 2009, 52 (12), 2616–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Ma X; Zhang J; Deng R; Ding S; Gu N; Guo X Synergistic effect of smoking with genetic variants in the AMPKalpha1 gene on the risk of coronary artery disease in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev 2014, 30 (6), 483–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).de la Monte SM; Tong M Brain metabolic dysfunction at the core of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem. Pharmacol 2014, 88 (4), 548–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Kroner Z The relationship between Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes: Type 3 diabetes? Altern Med Rev 2009, 14 (4), 373–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Najem D; Bamji-Mirza M; Chang N; Liu QY; Zhang W Insulin resistance, neuroinflammation, and Alzheimer’s disease. Rev. Neurosci 2014, 25 (4), 509–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Rosales-Corral S; Tan DX; Manchester L; Reiter RJ Diabetes and Alzheimer disease, two overlapping pathologies with the same background: oxidative stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity 2015, 2015, 985845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]