Abstract

Given the prominence of ethnicity/race in the United States, many youths construct an ethnic/racial identity (ERI). However, ERI development occurs against a backdrop of prejudice, oppression, and discrimination. This synthetic review explores (a) how identity and discrimination are related and (b) their association with psychological health. There is a reciprocal developmental association between ERI and discrimination, in which each informs the other. Although discrimination is detrimental for mental health, its impact depends on identity. In some cases, ERI confers protection from discrimination, and in others, it poses additional vulnerabilities. A strong sense of commitment to one’s identity confers protection against the negative effects of discrimination, while high levels of identity exploration are associated with increased vulnerability. However, the importance of ethnicity/race to one’s identity both protects from and increases vulnerabilities to discrimination. Suggestions for future research to help to disambiguate these associations are offered.

Keywords: ethnicity, race, identity, discrimination, health

“Who am I?” is not just an existential question but a developmental one. Youths struggle with this question as they develop a sense of self that is both independent from and connected to peers, friends, and family. Identity formation is a key developmental task (Yip, 2014); but for ethnic/racial minority youths in the United States and many other countries, identity construction occurs in a sociocultural context rife with racism and prejudice (Coll et al., 1996). These messages are often conveyed as ethnic/racial discrimination, which is defined as pervasive unfair treatment that is inextricably embedded in social structures and institutions (Krieger, 1999; Priest et al., 2013). In societies such as the United States where ethnicity/race are intimately tied to where people live, where they go to school, access to health care, and health itself, ethnic/racial discrimination has both measurable and immeasurable influences on how youths develop an identity.

Youths’ identity, both where they are developmentally in the formation of their ethnic/racial identity (ERI) and how they feel about their identity, influences the ways in which youths experience, interpret, and respond to discrimination (Sellers & Shelton, 2003). This synthetic review unpacks the reciprocal and complex ways in which ERI and discrimination inform each other and how they jointly impact psychological health among youths in the United States. This area of research is equivocal and without consensus. This ambiguity results from demographic diversity (e.g., ethnic/racial groups, age, socioeconomic status, immigration status, language, geography) and methodological diversity (e.g., epistemological view-points, disciplines of psychology, measurement instruments, research designs). Future research that delves deeper into the sources of this diversity may hold the key to identifying clear and distinguishable conclusions.

What Is ERI?

The complex natures of ERI and discrimination make it difficult to understand how they are related. ERI is considered to be a multifaceted constellation of one’s feelings, thoughts, and attitudes related to membership in an ethnic/racial group. ERI includes both the overall importance of ethnicity/race to one’s identity and feelings about one’s ethnic/racial group membership (Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton, & Smith, 1997). Researchers have ascribed a universal developmental process across diverse groups (e.g., African Americans, Asian Americans, Latinxs), focusing on the feelings, thoughts, and behaviors associated with exploring the meaning of ethnicity/race, as well as psychological feelings of connectedness and commitment to one’s group (Phinney, 1992). It is also understood that although family, peer, school, neighborhood, and societal contexts impact how ERI develops from adolescence to adulthood (Yip, Douglass, & Shelton, 2013; Yip, Seaton, & Sellers, 2010), ERI remains relatively stable from one situation and one day to the next (Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998; Yip, 2005; Yip & Fuligni, 2002). At the same time, the psychological salience or relevance of that ERI changes across situations and days depending on characteristics of the immediate context (Cross & Strauss, 1998; Sellers et al., 1998; Yip, 2005, 2014; Yip & Douglass, 2013; Yip & Fuligni, 2002).

What Is Ethnic/Racial Discrimination?

Although youths have agency in their ERI development, forming a coherent sense of self is informed by a sociocultural context that includes ethnic/racial discrimination. Ethnic/racial discrimination is considered to be differential, typically unfair treatment due to membership in a marginalized ethnic/racial group. Ethnic/racial discrimination resides in a larger, intricate system of racism, prejudice, and oppression privileging the experiences of people in power while devaluing the experiences of others (Coll et al., 1996). In daily life, these social and institutional inequities are made proximal and relevant through interpersonal interactions. Discrimination conveys messages of inferiority and marginalized status sourced from perpetrators such as peers, teachers, adults, and strangers of all ages and backgrounds. Moreover, the source of discrimination has a differential impact on adolescent health (Benner & Graham, 2013). Although discrimination does not occur frequently (i.e., 1–2 times a week), it is a normative experience for ethnic/racial minority youths, and its impact on their health cannot be ignored (Hughes, Del Toro, Harding, Way, & Rarick, 2016; Schmitt, Branscombe, Postmes, & Garcia, 2014; Umaña-Taylor, 2016). Despite racism’s structural pervasiveness, interpersonal discrimination is relatively infrequent yet has robust negative effects on health.

How Are ERI and Discrimination Related to Each Other?

Connecting the dots between ERI and discrimination is increasingly important in a society that at once grapples with a growing, soon-to-be majority of ethnic/racial minority citizens (Colby & Ortman, 2015) and corresponding increases in national and regional bias-related crimes (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2016). Milestones in ERI development in adolescence and young adulthood are coupled with increases in discrimination experiences (Hughes et al., 2016), and these experiences are particularly influential for health both during adolescence and later adulthood (Adam et al., 2015; Schmitt et al., 2014). How do ethnic/racial youths reconcile the need to form a healthy and integral identity in a sociocultural context that communicates their devalued and marginal status?

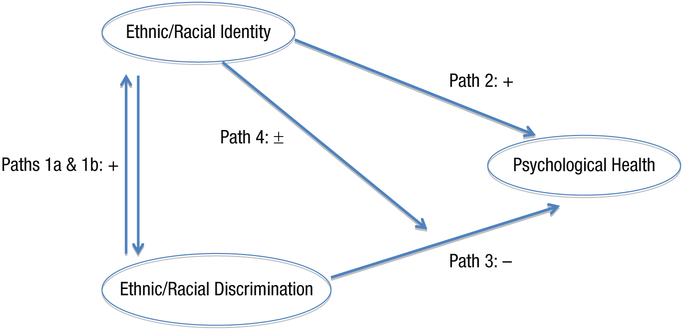

Discrimination and ERI inform each other (see Fig. 1, Paths 1a and 1b). Prejudice and discrimination increase identification with one’s ethnic/racial group (Path 1a; Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, 1999). Since discrimination conveys rejection from the dominant group, some ethnic/racial minorities recognize that inclusion in the dominant group is unlikely. Instead, these ethnic/racial minorities choose to identify more strongly with their own group, despite its marginalized status. Indeed, discrimination may serve as an impetus to seeking out information about youths’ membership in a marginalized group (Brittian et al., 2015; Pahl & Way, 2006). In other cases, ethnic/racial minorities may be more determined to gain acceptance from the majority and downplay their ethnicity/race (Cheryan & Monin, 2005).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the associations between ethnic/racial identity (ERI), discrimination, and psychological well-being. Path 1a depicts a positive association from discrimination to ERI. Path 1b depicts a positive association from ERI to discrimination. Path 2 depicts a positive association between ERI and psychological health. Path 3 depicts a negative association from ethnic/racial discrimination to psychological health. Path 4 depicts a positive and negative moderating influence of ERI on the impact of discrimination on psychological health.

At the same time, where youths are in their identity development and how they feel about their ethnic/racial group membership might impact their perceptions and experiences of discrimination (Fig. 1, Path 1b; Seaton, Yip, & Sellers, 2009; Torres & Ong, 2010). Yet specificity about ERI dimensions matters. Individuals who rate ethnicity/race as important to their overall sense of self, as well as those who are still in the process of exploring their identity, are more likely to report experiences with discrimination (Burrow & Ong, 2010; Pahl & Way, 2006; Sellers & Shelton, 2003). On the other hand, individuals who report feeling better about their ethnic/racial group membership report fewer experiences with discrimination (Burrow & Ong, 2010).

How Are ERI and Discrimination Related to Psychological Health?

There are several ways that ERI, discrimination, and psychological health could be related; the most common investigations make two foundational assumptions. The first is that ERI promotes psychological health (Fig. 1, Path 2). The second is that discrimination is detrimental for psychological health (Fig. 1, Path 3). Recent meta analyses and systematic reviews support both claims (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Priest et al., 2013; Rivas-Drake et al., 2014). Given that ERI and discrimination influence each other, how do they jointly influence health?

How ERI and discrimination impact psychological outcomes is equivocal (Fig. 1, Path 4; Yip, Gee, & Takeuchi, 2008). Empirical confusion is further confounded by theoretical divergences, with some researchers suggesting that identity should defend against the vulnerabilities associated with discrimination, while others suggest that identity should exacerbate these vulnerabilities (Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Turner, 1985). What is clear is that ERI and discrimination work together to impact psychological health; yet the nature of this association depends on the dimension of identity. For example, individuals who are still in the process of grappling with their ethnicity/race (i.e., ERI exploration) seem to be especially negatively impacted by experiences of discrimination (Torres & Ong, 2010). On the other hand, individuals who have committed to their ethnic/racial group membership seem to be protected against the detriments of discrimination (Romero, Edwards, Fryberg, & Orduña, 2014; Stein, Kiang, Supple, & Gonzalez, 2014).

However, when one considers the association between discrimination and outcomes for youths who have decided that ethnicity/race is important to their overall sense of self, there is no clear pattern. Some research finds the importance of ethnicity/race to be more damaging (Yip et al., 2008), while other research finds it to be protective (Sellers, Caldwell, Schmeelk-Cone, & Zimmerman, 2003). A recent meta-analysis found an equal number of studies supporting the benefits and detriments of ERI for the effects of discrimination on mental health outcomes (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009). Notably, other research has failed to show an effect of identity altogether (Seaton, Neblett, Upton, & Hammond, 2011). In part, the lack of consensus may be attributable to the diversity of ethnic/racial groups, ages, nativity status, measures, and psychological outcomes.

And yet the key to achieving consensus may lay in this diversity. A recent meta-analysis explored how diversity may be contributing to the obscurity in the literature (Yip, Wang, Mootoo, & Mirpuri, 2018). For example, samples with a larger proportion of Latinx and Asian American participants (compared with African American participants) are more likely to observe a protective effect of ERI commitment. Feeling good about one’s ethnicity/race (i.e., private regard) was associated with a stronger exacerbating effect for samples with more Asian American compared with African American and Latinx participants. Believing that other people hold one’s ethnic/racial group in high esteem (i.e., public regard) was associated with a stronger buffering effect for samples with more Asian (relative to African American) participants. These group differences are likely tied to the unique sociohistorical experiences of these groups. Gender also matters; exploring one’s ERI is more detrimental for health (particularly mental health) in samples with a larger proportion of females, suggesting qualitatively different experiences for women of color who must contend with a double minority status. Not surprisingly, age also matters. Exploring one’s ERI seems to have a peak exacerbating effect around age 23. Developmental research typically groups samples by broad age categories (Yip et al., 2008) or considers age to be a covariate rather than an important moderating variable; these results call for more fine-grained analyses of age. Finally, research methodology also matters; longitudinal research designs are more likely to reveal a weaker buffering effect of ERI commitment compared with cross-sectional approaches.

Conclusion and Future Directions

First, it is clear that identity development occurs within a sociocultural context of discrimination, and it is important to consider their mutual influence. Investing in more longitudinal research is one approach to teasing apart this reciprocal association, while acknowledging that research with ethnic/racial minorities can be more challenging and resource intensive (Hall, Yip, & Zárate, 2016). Another challenge for future research is that ERI development and discrimination occur on different time scales. ERI development is a process that unfolds over time, space, and context, while interpersonal discrimination is composed of discrete events experienced on a daily basis that have an acute impact on health and whose health effects also accumulate over time. Therefore, a combination of longer-term (e.g., annual, biannual) and shorter-term (e.g., daily diaries, experience sampling) longitudinal approaches is necessary to capture the bidirectional association between these constructs.

Second, where youths are and how they feel about their ERI matters for the psychological impact of discrimination. This area of research is too equivocal to draw broad conclusions from; however, meta-analytic approaches find that specifying the ERI dimension, ethnicity/race, gender, age, and study design matter for whether ERI is observed to protect or increase vulnerabilities associated with discrimination. Future research should also consider the role of nativity status, since moderating effects have been observed in United States–born but not foreign-born individuals (Yip et al., 2008); however, nativity status is not always assessed or reported (e.g., African American samples). It might also be fruitful to consider geographic region when comparing ethnic/racial minorities’ experiences in more and less diverse and in socially and politically conservative areas (Soto et al., 2012). Future research would also benefit from a broader focus on health. While meta-analyses have focused on the impact of discrimination on physical health outcomes (e.g., Priest et al., 2013), much less research has examined the moderating impact of ERI. In a recent meta-analysis, only 2 of 51 studies focused on physical health outcomes (e.g., illness, sleep; Yip et al., 2018). Relatedly, while meta-analyses typically aggregate various indices of psychological health, future research might aim to hone in on the effects of ERI for a single outcome, aiming to link specific sources and types of discrimination to specific domains and outcomes. Taking a whole-person (vs. variable-centered) perspective, it is important for future work to consider the intersections of social categories (e.g., Black women in the northeast).

Another area that undoubtedly contributes equivocality is measurement. There is no consensus on the best measures of ERI or discrimination. Sampling ERI measures alone, there are over six multidimensional (and countless other single-item) measures, many of which have undergone revision since initial publication. Some measures focus on developmental processes, while others focus on the meaning and significance of ethnicity/race. Within these two broader categories, some measures focus on the development of beliefs and values, while others focus on behavioral engagement. Even more confusing is that there are nearly 40 different measures of ethnic/racial discrimination. Some measures focus on frequency of events over different time spans (e.g., daily, monthly, lifetime), while others focus on the distress related to these experiences; some identify a perpetrator/source, while others do not; and some focus on direct experiences, while others include vicarious or group-based experiences.

There is still much research to be done. While discrimination may be associated with increases in ERI, research outside of the United States fails to reveal such associations (Lee, Noh, Yoo, & Doh, 2007). There may be universal commonalities across minority groups all over the world; however, experiences are couched in unique sociohistorical and cultural contexts. Future research should continue to consider the importance of immediate and proximal as well as distal contexts that influence ERI, discrimination, and their joint impact on psychological health. Endeavoring to appreciate both how ERI confers protection and vulnerabilities can help elucidate what it means to be an ethnic/racial minority. While it is important to acknowledge the multiple and distinct dimensions of ERI, it is also important to remember that these dimensions come together to form a coherent sense of self. Some research seems to suggest that importance and exploration of identity is maladaptive, whereas feeling good about one’s group is beneficial; however, it is important to remember that in most cases, individuals who have decided that ethnicity/race is important also feel good about their group membership (Sellers et al., 1997; Yip, Seaton, & Sellers, 2006).

The solution to protecting youths from the discriminatory correlates of ERI is not to de-emphasize its importance or to deter its exploration but to cultivate a deep sense of pride and affection for one’s group, regardless of, and perhaps in spite of, societal values. We cannot easily eliminate or mitigate the negative impact of deeply entrenched social and institutional prejudices and oppression, whose historical foundations predate the research reviewed here, but we can begin to cultivate esteem and positive regard in all youths regardless of their backgrounds.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared that there were no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship or the publication of this article.

Recommended Reading

- Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B, Truong M, Karlsen S, & Kelly Y (2013). (See References). A recent international systematic review of research on the health effects of discrimination among youths. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Seaton EK, Markstrom C, Quintana S, Syed M, Lee RM, … Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development, 85, 40–57. A recent review of ethnic/racial identity and health among adolescents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Syed M, Yip T, Knight GP, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Rivas-Drake D, & Lee RM (2014). Methodological issues in ethnic and racial identity research with ethnic minority populations: Theoretical precision, measurement issues, and research designs. Child Development, 85, 58–76. A recent discussion of methodological issues related to ethnic/racial identity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T (2014). (See References). An empirical article underscoring the daily experiences of ethnic/racial identity among ethnic/minority adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Gee GC, & Takeuchi DT (2008). (See References). An analysis of the moderating impact of ethnic/racial identity on the association between discrimination and health in a nationally representative sample highlighting the importance of nativity status. [Google Scholar]

References

- Adam EK, Heissel JA, Zeiders KH, Richeson JA, Ross EC, Ehrlich KB, … Eccles JS (2015). Developmental histories of perceived racial discrimination and diurnal cortisol profiles in adulthood: A 20-year prospective study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 62, 279–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Graham S (2013). The antecedents and consequences of racial/ethnic discrimination during adolescence: Does the source of discrimination matter? Developmental Psychology, 49, 1602–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe N, Schmitt M, & Harvey R (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Brittian AS, Kim SY, Armenta BE, Lee RM, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Schwartz SJ, … Hudson ML (2015). Do dimensions of ethnic identity mediate the association between perceived ethnic group discrimination and depressive symptoms? Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21, 41–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrow AL, & Ong AD (2010). Racial identity as a moderator of daily exposure and reactivity to racial discrimination. Self and Identity, 9, 383–402. [Google Scholar]

- Cheryan S, & Monin B (2005). “Where are you really from?”: Asian Americans and identity denial. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 717–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby SL, & Ortman JM (2015). Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 to 2060. Retrieved from https://census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf

- Coll CG, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, Garcia HV, & McAdoo HP (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67, 1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE Jr., & Strauss L (1998). The everyday functions of African American identity In Swim JK (Ed.), Prejudice: The target’s perspective (pp. 267–279). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall GCN, Yip T, & Zárate MA (2016). On becoming multicultural in a monocultural research world: A conceptual approach to studying ethnocultural diversity. American Psychologist, 71, 40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Del Toro J, Harding JF, Way N, & Rarick JR (2016). Trajectories of discrimination across adolescence: Associations with academic, psychological, and behavioral outcomes. Child Development, 87, 1337–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N (1999). Embodying inequality: A review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. International Journal of Health Services, 29, 295–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM (2005). Resilience against discrimination: Ethnic identity and other-group orientation as protective factors for Korean Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Noh C-Y, Yoo HC, & Doh H-S (2007). The psychology of diaspora experiences: Intergroup contact, perceived discrimination, and the ethnic identity of Koreans in China. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13, 115–124. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.2.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, & Roberts SO (2013). Racial identity and autonomic responses to racial discrimination. Psychophysiology, 50, 943–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K, & Way N (2006). Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity among urban Black and Latino adolescents. Child Development, 77, 1403–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, & Smart Richman L (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 531–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS (1992). The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7, 156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B, Truong M, Karlsen S, & Kelly Y (2013). A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Social Science & Medicine, 95, 115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Syed M, Umaña-Taylor A, Markstrom C, French S, Schwartz SJ, … Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. (2014). Feeling good, happy, and proud: A meta-analysis of positive ethnic–racial affect and adjustment. Child Development, 85, 77–102. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Edwards LM, Fryberg SA, & Orduña M (2014). Resilience to discrimination stress across ethnic identity stages of development. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt MT, Branscombe NR, Postmes T, & Garcia A (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 921–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Neblett EW, Upton RD, & Hammond WP (2011). The moderating capacity of racial identity between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being over time among African American youth. Child Development, 82, 1850–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Yip T, & Sellers RM (2009). A longitudinal examination of racial identity and racial discrimination among African American adolescents. Child Development, 80, 406–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01268.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Caldwell CH, Schmeelk-Cone KH, & Zimmerman MA (2003). Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44, 302–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM, Shelton JN, & Smith MA (1997). Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: A preliminary investigation of reliability and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 805–815. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, & Shelton JN (2003). The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 1079–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Smith MA, Shelton JN, Rowley SAJ, & Chavous TM (1998). Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2, 18–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto JA, Armenta BE, Perez CR, Zamboanga BL, Umana-Taylor AJ, Lee RM, … Ham SL (2012). Strength in numbers? Cognitive reappraisal tendencies and psychological functioning among Latinos in the context of oppression. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18, 384–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern Poverty Law Center. (2016, December 16). Update: 1,094 bias-related incidents in the month following the election. Hatewatch. Retrieved from https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2016/12/16/update-1094-bias-related-incidents-month-following-election

- Stein GL, Kiang L, Supple AJ, & Gonzalez LM (2014). Ethnic identity as a protective factor in the lives of Asian American adolescents. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 5, 206–213. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, & Turner JC (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict In Austin WG & Worchel S (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Monterey, CA: Brooks-Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Torres L, & Ong AD (2010). A daily diary investigation of Latino ethnic identity, discrimination, and depression. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 561–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC (1985). Social categorization and the self-concept: A social cognitive theory of group behavior In Lawler EJ (Ed.), Advances in group processes: Theory and research (pp. 77–122). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ (2016). A post-racial society in which ethnic-racial discrimination still exists and has significant consequences for youths’ adjustment. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25, 111–118. doi: 10.1177/0963721415627858 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T (2005). Sources of situational variation in ethnic identity and psychological well-being: A Palm Pilot study of Chinese American students. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1603–1616. doi: 10.1177/0146167205277094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T (2014). Ethnic identity in everyday life: The influence of identity development status. Child Development, 85, 205–219. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, & Douglass S (2013). The application of experience sampling approaches to the study of ethnic identity: New developmental insights and directions. Child Development Perspectives, 7, 211–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Douglass S, & Shelton JN (2013). Daily intragroup contact in diverse settings: Implications for Asian adolescents’ ethnic identity. Child Development, 84, 1425–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, & Fuligni AJ (2002). Daily variation in ethnic identity, ethnic behaviors, and psychological wellbeing among American adolescents of Chinese descent. Child Development, 73, 1557–1572. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Gee GC, & Takeuchi DT (2008). Racial discrimination and psychological distress: The impact of ethnic identity and age among immigrant and United States-born Asian adults. Developmental Psychology, 44, 787–800. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Seaton EK, & Sellers RM (2006). African American racial identity across the lifespan: Identity status, identity content, and depressive symptoms. Child Development, 77, 1504–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00950.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Seaton EK, & Sellers RM (2010). Interracial and intraracial contact, school-level diversity, and change in racial identity status among African American adolescents. Child Development, 81, 1431–1444. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01483.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Wang Y, Mootoo C, & & Mirpuri S (2018). Moderating the association between discrimination and adjustment: A meta-analysis of racial/ethnic identity. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]