Abstract

Community engagement (CE) has come to the forefront of academic health centers’ (AHCs) work because of two recent trends: the shift from a more traditional ‘treatment of disease’ model of health care to a population health paradigm (Gourevitch, 2014), and increased calls from funding agencies to include CE in research activities (Bartlett, Barnes, & McIver, 2014). As defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, community engagement is “the process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1997, p. 9). AHCs are increasingly called on to communicate details of their CE efforts to key stakeholders and to demonstrate their effectiveness.

The population health paradigm values preventive care and widens the traditional purview of medicine to include social determinants of patients’ health (Gourevitch, 2014). Thus, it has become increasingly important to join with communities in population health improvement efforts that address behavioral, social, and environmental determinants of health (Michener, et al., 2012; Aguilar-Gaxiola, et al., 2014; Blumenthal & Mayer, 1996). This CE can occur within multiple contexts in AHCs (Ahmed & Palermo, 2010; Kastor, 2011) including in education, clinical activities, research, health policy, and community service.

Keywords: community engagement, community scholarship, process evaluation, evaluation – institutional change, academic health center

Introduction

While AHCs are under increased pressure to demonstrate the effectiveness of their community engaged activities, there are multiple challenges to developing effective evaluation methods for CE in AHCs (CDC, 1997; Rubio, et al., 2015). Simple concepts like CE can be difficult to define (Rubio, et al., 2015). Demonstrating the impact of CE on population health outcomes is problematic (Szilagyi, et al., 2014), and leadership-level knowledge of an AHC’s CE activities within their own institutions may be limited (Eder, Carter-Edwards, Hurd, Rumala & Wallerstein, 2013). This paper describes our work to develop replicable processes that evaluate ongoing CE efforts within AHCs from an institutional level, and assesses the levels of CE resources, as compared to best practices.

The University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) created the Institutional Community Engagement (CE) Self-Assessment (ICESA) project, a two-phase pilot that creates a map of an AHC’s CE efforts, and measures existing institutional capacity for supporting CE activities. Phase 1, the URMC Framework model (Szilagyi, et al., 2014), uses a health services research approach (Starfield, 1973) to evaluate an AHC’s CE program. Phase 2 involves the completion of the Institutional CE Self-Assessment developed by Community Campus-Partnerships for Health (CCPH) (Gelmon, Seifer, Kauper-Brown, & Mikkelsen, 2005). For this pilot, the URMC solicited participation from AHCs who were seeking, or who had already been awarded Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSAs) from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. These awards fund medical research institutions to speed the translation of research discovery into improved patient care and strongly encourage the inclusion of CE activities toward this goal (Westfall, et al, 2012). Eight institutions participated in this pilot project.

The purpose of the pilot project is not to assess the content of each institution’s Framework and CCPH Self-Assessment, nor to make comparisons across participating institutions, but to assess the effectiveness of the process. Specifically, does the two-phase process help AHCs identify and map current CE efforts, identify institutional resources and potential gaps to set future strategic CE goals, and assist institutions in describing their CE efforts to internal and external stakeholders?

Methods

Below, we provide an overview of the ICESA two-phase project, a description of the project scope and team composition, a review of the data sources, and a description of our analytic approach.

Overview of the ICESA Two-Phase Project

Phase 1.

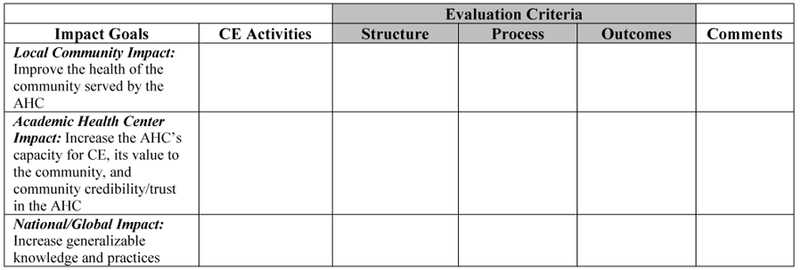

Institutional partners were asked to form teams and to apply the URMC Framework (Szilagyi, et al., 2014) that was developed in 2013 and categorizes an AHC’s CE activities around three levels of impact: on the surrounding local community, on the AHC, and on population health through generalizable knowledge and practices (Kastor, 2011). The Framework’s aim is to document and assess the structure, process, and outcomes of major CE activities, including large-scale, multicomponent efforts (which may be longstanding and can span many disciplines) designed to achieve each CE goal. The Framework does not attempt to provide quantifiable measures, but instead contextualizes an AHC’s current CE activities to provide a baseline for evaluation and tracking progress over time. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

URMC Framework of CE Activities

Phase 2.

In the second phase of the project, ICESA partners were asked to complete the CCPH CE Self-Assessment (Gelmon, et al., 2005). This instrument, created in 2005 and subsequently refined, assesses the capacity of a higher educational institution for CE and community-engaged scholarship, and identifies opportunities for action (Gelmon, Lederer, Seifer, & Wong, 2009; Gelmon, Blanchard, Ryan, & Seifer, 2012; Gelmon, et al., 2005). Using the self-assessment has helped identify variation in capacity for CE, as well as focus on areas for development (Gelmon et al., 2009).

The CCPH CE Self-Assessment contains six dimensions, each with multiple elements. The six dimensions are: definition of CE, faculty support for and involvement in CE, student support for and involvement in CE, community support for and involvement in CE, institutional leadership and support for CE, and community-engaged scholarship.

Within each dimension, four levels of commitment to CE and community engaged-scholarship are noted. Figure 2 illustrates how each element is described.

Figure 2.

Example of CCPH CE Self-Assessment Dimension and one of its Elements

The results of the CCPH CE Self-Assessment highlight which “best practice” resources the institution possesses to focus its efforts toward CE activities, any gaps in “best practice” resources available at the institution, and opportunities for future improvement.

To ensure similar methodology across the sample, we asked that team members at each AHC work to come to consensus on a single rating for each CCPH Assessment dimension.

Combining the URMC Framework with the CCPH CE Self-Assessment offers a unique opportunity to both compile current efforts and examine gaps in institutional resources, policies, and infrastructure for CE compared to best practices.

Project scope and team composition

Seven of the eight AHCs focused on CE across all of their mission areas, as defined by each AHC; one team focused exclusively on CE applied to research. All eight teams excluded considerations of undergraduate programs that sit outside the AHC.

Each institutional contact from participating AHCs served as a team leader, and that leader assembled a local project team comprised of faculty, administrators and staff from his or her institution. Based on lessons learned from the prior Framework project conducted at the URMC (Szilagyi, et al., 2014), project leaders assembled five to ten people who were explicitly familiar with CE efforts occurring at their respective AHCs. Where possible, team leaders were encouraged to solicit a broad representation from across departments, but the priority was to include team members most familiar with the CE efforts of the AHC.

The content produced by the two-phase project reflected highly detailed, internal information on AHC CE programs and policies. Given that the ICESA project focus was on an internal assessment of AHC CE capacity, team leaders agreed that community partners would not be included on the project teams. Instead, the project leaders recommended that community partners be provided with a report on the findings, give feedback and suggestions on the report, and be included in CE planning efforts. This decision was supported by consultants from CCPH, who agreed that the Phase 2 CCPH Self-Assessment is, by design, internally-focused on the AHC. To that end, approximately 18 months after the conclusion of Phase 2 of the project, team leaders were asked to complete a short survey describing their plans for sharing with their community partners the results of their institutions’ two-phase process.

Data collection and analysis

A multi-faceted evaluation used qualitative data from the following sources:

The Phase 1 URMC Framework and Phase 2 CCPH CE Self-Assessment comments and notes from the eight participating AHCs. The open comment and note fields provided additional information.

Team Feedback Survey. All team leaders reported their experiences using the Phase 1 URMC Framework, Phase 2 CCPH CE Self-Assessment, and overall assessment of the effectiveness of the ICESA project.

Additional Qualitative Data. These data included email communications and notes from both one-to-one phone calls and monthly project leader conference calls.

Supplemental Survey. Approximately 18 months after Phase 2 of the project, team leaders completed a short, on-line survey in which they were asked details about their plans for sharing their institutions’ results of the two-phase process with community partners.

The project directors took a structured directed approach to content analysis. In contrast to an inductive, open coding approach, the initial coding in a structured directed approach is based on predetermined categories (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).The predetermined categories were represented by three process evaluation questions. The project directors compiled the notes and comment fields from the data sources listed above into a single document. Separately, and on individual copies, they highlighted all comments that aligned with either a positive or negative answer to each process evaluation question. Individually, they labelled each comment as to the process evaluation question addressed, and further subcategorized those comments conceptually related within each category. Any text that did not fit in this initial categorization scheme was given another code and analyzed to determine if it represented a new category. The project directors came to consensus on which data provided evidence (or not) for each process evaluation question and agreed on subcategories. All results of the content analysis were shared with the other team leaders for feedback, discussion and agreement. Agreed upon changes were made; all project team leaders reached consensus on the coding. Additionally, there were questions on the Feedback Survey that directly addressed the process evaluation questions. Those results are included below.

Results

Does the ICESA two-phase process help AHC’s identify and map current CE efforts?

The evidence for this question is found in the following sources: the completed URMC Framework from all eight participating institutions; the answers to questions on the feedback survey; and the categorized open comments made by project team leaders.

All eight teams completed the URMC Framework. Four institutions modified the Framework to suit their individual purposes by modifying the names of column headings (N=1), or by adding columns or rows (N=3), increasing the granularity of the data captured. On the feedback survey, responses to “Overall, how useful was the Framework in documenting/understanding your CE program?” showed that all eight project leaders found it useful, half noting it as “very useful” (N=4) and half as “somewhat useful” (N=4).

Project team leaders were also asked about the utility of the URMC Framework and the ICESA two-phase process as a whole for identifying and mapping current CE efforts. Eight team leaders provided comments affirming the usefulness of the two-phase process (N=8). Open comments were more descriptive and organized into three subcategories. The first subcategory is centered on “mapping” or visualizing the CE programs at participating institutions. Representative comments from team leaders include “extremely helpful in mapping and understanding the CE efforts that were happening across the academic health center” and “helped us see all of our CE activities and creates a baseline for planning activities moving forward, and for tracking our successes.”

The second subcategory includes comments made by team leaders about the modifications they made to the URMC Framework, mentioned above.

There were also suggestions for how to improve the use of the URMC Framework; the final subcategory highlights the difficulties some teams had in utilizing the URMC Framework and their suggested changes for future use. Five team leaders made suggestions (N=5). In summary, team leaders indicated that, in Phase 1, more guidance on the URMC Framework, with examples given, would have been welcomed, particularly to assist those not familiar with health services research and in describing the purpose of the URMC Framework. One team leader remarked that “The framework was a little confusing. It wasn’t obvious on how to complete it at first. Once we walked through it a bit it became much easier!” Other suggestions for improvement included providing additional guidance on identifying site team members and adding a facilitator to work with each institutional team.

Does the Two-Phase Process assist in identifying institutional resources and potential gaps in order to set strategic CE goals for the future (CCPH CE Self-Assessment)?

Where the URMC Framework was the primary tool for identifying and mapping CE efforts, the CCPH CE Self-Assessment was designed to prompt consideration and assessment of available institutional resources for supporting CE, and identification of potential institutional gaps.

Seven teams completed the CCPH CE Self-Assessment. The team leader of the eighth reported that, given their AHC’s size and number of programs, the team members questioned their ability to accurately determine ‘level of AHC institutional capacity’ for CE work across the six dimensions.

When asked on the feedback survey “Will this process help you, or others at your institution, set strategic goals to further CE efforts at your institution?” all eight team leaders responded “yes.”

Additional evidence related to this question came from open comments on the feedback survey and comments made in project meetings. These were categorized into two subcategories: descriptions of the types of institutional gaps that were identified by teams and evidence that the ICESA project supports strategic CE goal setting.

Seven team leaders commented on potential institutional gaps identified by the project (N=7). Comments included statements such as “It became clear that while there are abundant resources to support CE scholarship, there are significant barriers to promotion, communications, and utilization of these resources” and “While engagement activities are occurring (in some cases, individual centers and institutes are doing this well), there is little emphasis on what the community needs. The activities are driven more by institutional priorities.”

Project team leaders also provided feedback, either in the follow up survey or project meetings, suggesting the two-phase process has helped or likely will help inform future CE planning. All eight team leaders expressed plans, variously, to use the results from this project for identifying priority areas, developing strategies, or setting CE goals in the future. One team leader reported that the CE task force at her institution has already utilized the results from this project to help set strategic goals.

Does the Two-Phase Process assist participating institutions in describing their CE efforts to internal and external stakeholders?

On the feedback survey, team leaders were asked “How will you, or others at your institution, share the results of this two-phase process?” All eight team leaders indicated that they will share the results. Seven teams will share the results with their CTSA leadership (N=7), four teams intend to share the results with their community partners (N=4), and three with departmental leadership (N=3). In open comments, one institution reported that it has plans to share the results with the leadership of each school across the AHC, and one institution reported plans to publish and present the results locally and nationally.

In the follow up Supplemental Survey, conducted 18 months after completion of the project, team leaders were asked “Have you already shared the results of your ICESA with your community partners?” One team replied “yes”, indicating that the results had been included in oral presentations, committee meeting discussion, and in written reports. Seven teams responded “no”. Those seven teams were asked the follow-up question “Do you intend to share your ICESA results with community partners. Six teams replied “yes”; one team leader indicated that the team would not share the results with community partners, citing the difficulty of contextualizing the results across broad community partnerships. The six teams who indicated plans to share the results with community partners were asked the follow-up question “How do you intend to share your results with your community partners?” Five teams indicated that the results would be presented for discussion and feedback to their community advisory boards (N=5). Two teams plan to share the results for discussion at upcoming meetings with community partners (N=2) and one team plans to follow their presentation at their community advisory board and partnership meetings with key informant interviews to elicit feedback (N=1). Team leaders were also asked “How will you, or others at your institution, use the results of this Two-Phase Process?” All eight team leaders indicated that they will use their results. Seven indicated they will use the results in their CTSA reporting (N=7). Six teams now plan to identify additional outcome or impact measures (N=6). Five endorsed that they will use their results to increase the visibility of CE work within their respective institutions (N=5). Four plan to use the results to create programs or initiatives to address gaps in their CE efforts (N=4). Two team leaders plan to use the results in their CTSA renewal application (N=2).

Open comments from the feedback survey and project meetings were categorized into two subcategories: ways in which the ICESA project increased communication with stakeholders during the project, and how team leaders expect the project will help them describe their CE efforts to internal and external stakeholders going forward. Representative comments can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Does the Two-Phase Process assist participating institutions in describing their CE efforts to internal and external stakeholders?

| Subcategories | Project Leader’s Comments |

|---|---|

| Increased Communication with Internal Stakeholders, During the Project |

• Team members learned quite a bit about each other's areas • A representative from the University's Office for Public Engagement participated in this assessment process • Allowed for conversations and thus awareness across offices with common and unique CE missions that didn't know of each other or work together • The thoughtfulness that surrounded the framework was invigorating. To me the best part of the process was the conversations about CE that resulted • It also provided an opportunity for the team to develop working relationships as several of the team members had not known each other prior to the project initiation • All extremely helpful to create common language across 3 schools in our Health Sciences • The greatest benefit of the project was the opportunity to gather people for whom CE is a major part of their job, but who had never had the chance to meet or spend time with their CE colleagues |

| Outcomes of Two- Phase Process Will Help in Describing CE Efforts to Internal and External Stakeholders |

• Beyond this project, they [higher ups] plan to advance a more comprehensive survey effort across 3 schools based on the associate dean’s feedback • I'd like to share with the deans of participating schools. The provost will also be informed of findings. • Because they were not involved in the self-assessment process, it will be critical to hear their [community partners’] feedback and include them in setting priorities and goal setting • Lend[s] unique insight into how to share our findings back to leadership and how to make it (hopefully!) easy for them to move this forward • It really sets the stage for discussion • It gives very specific information for reporting to the community and the institution • Quantified a very difficult construct that can start a conversation with University leaders. Make CE a real thing and not just something we talk about |

All eight team leaders indicated that they intend to share the results with internal stakeholders and four team leaders indicated that they will also share the results with community partners (N=8). Four of the eight team leaders made comments about the ways in which the ICESA project will help them with these communications (N=4); for example, one team leader said that participation in the project “gives very specific information for reporting to the community and institution” and another said it “quantified a very difficult construct that can start a conversation with University leaders.” In addition to setting the stage for institutional conversations about CE, the 2-phase process and results also provided an opportunity to engage with community partners and other external stakeholders about institutional capacity for CE and opportunities for growth and innovation.

Discussion

Overall, our findings suggest that the ICESA two-phase process helped participating AHCs identify and map current CE efforts, identify institutional resources and potential gaps in order to set strategic CE goals for the future, and describe their CE efforts to internal and external stakeholders. All team leaders from the eight participating institutions found implementing the ICESA project in an AHC to be beneficial. One unanticipated finding, however, is the extent to which the participating institutions modified the URMC Framework to suit their purposes. Institutions added columns and rows, or made changes to the column headings in the Framework that did not fundamentally alter the character or use of the tool, but which increased its utility for those institutions. This adaptability suggests that it acts as a heuristic tool; the use of the Framework became an iterative process guided by each team’s subjective and emergent needs.

Two additional experiences suggest another way that the Framework acts as a heuristic tool. One team leader reported that it was difficult to be sure her team had captured all CE activities from across the AHC. Another was concerned, while pulling together her team, that she may not be aware of some CE-active faculty in other departments (see Table 1). From an instrumental standpoint, the inability to exhaustively capture all CE activities across departments and schools in an AHC, or to know where to look for CE faculty in a given department could seem like a process failure, but from an epistemological standpoint, bringing those potential gaps to the foreground is one of this project’s goals. One project leader reported that in the process of making inquiries of other departments to identify CE-engaged faculty members to join the team for this project, she met a faculty member who was heretofore unknown to her; they are now considering future collaborations. Another project leader reported that, as a result of utilizing the URMC Framework, senior leadership at her institution are now interested in creating an online capture system for eliciting CE activities information from across the AHC in a more institutionally-supported manner.

Table 1.

Does the Two-Phase Process help AHC’s identify and map current CE efforts? (URMC Framework)

| Subcategories | Project Leader’s Comments |

|---|---|

| Mapping CE Efforts |

• Helped us see all of our CE activities and it creates a baseline for planning activities moving forward, and for tracking our successes • Helpful in assisting us to identify gaps • A mechanism to catalog CE work • Extremely helpful in mapping and understanding the CE efforts that were happening across the academic health center |

| Adaptability of the URMC Framework; Implemented |

• Separated out activities and evaluation criteria by department/office/center, and added a locations column • Added columns for school, lead contact and audience served • Used 3 original goals, but modified and added some • The URMC model was very useful in helping us begin this conversation. However, we had to revamp the model to guide our conversation in a way that worked for us • We had a lot of discussion about what the column headings would be and what information would fit for each one |

| Challenges in using the URMC Framework and Suggested Changes |

• Would have been helpful to the institution to include source/PI to know/remember where to get the data • Assessment of quantity vs. quality of programs could be helpful • Perhaps adding some step by step on how to walk through the process. A series of questions to ask the team to elicit the information. Once we got started the process seemed to flow. Getting started was the tough part. Maybe even a facilitator to work through that can objectively place items in the right areas or push the group to consider other aspects of CE • Difficult to differentiate between structure, process, outcomes • Had trouble determining who to bring to the table • Somewhat difficult to assure that they had accurate data on all existing programs and research projects related to CE • The framework was a little confusing. Once we walked through it a bit it became much easier! |

At this time, there are no plans to repeat this project as a national, multi-institutional effort; this is appropriate to the focus of the project on institutional self-assessment. As next steps, the project leaders recommend participating institutions share their results with their community partners and repeat this two-phase process at a regular interval, to be determined by their individual needs. The challenges participating teams experienced in using the URMC Framework, and their recommendations for changes, should be well-considered in future implementations of ICESA, by both our participating teams, and others who may utilize the process.

Table 2.

Does the Two-Phase Process assist in identifying institutional resources and potential gaps in order to set strategic CE goals for the future (CCPH CE Self-Assessment)?

| Subcategories | Project Leader’s Comments |

|---|---|

| Examples of gaps identified |

• Somewhat difficult to assure that they had accurate data on all existing programs and research projects related to CE • While engagement activities are occurring (in some cases, individual centers and institutes are doing this well), there is little emphasis on what are the community needs. The activities are driven more by institutional priorities • The lack of resources remain a challenge in getting CE plans fully implemented • It became clear that while there are abundant resources to support CE scholarship, there are significant barriers to promotion, communication, and utilization of these resources • We found the framework helpful in assisting us to identify gaps. During our discussion about our gaps we figured out that not many of us are measuring the effectiveness of different approaches of community engaged research • It is an area that is talked about and referenced but has never been quantified. This assessment quantifies some of the challenges, identifies areas of improvement • We learned that the institution has definitions and recommended practices in place but those are interpreted differently across the various schools |

| Supporting Strategic Goal Setting |

• This assessment quantifies some of the challenges, identifies areas of improvement. It really sets the stage for discussion • The documents from the process will be referred to when setting goals for the various projects, departments, etc. that involve CE that we are involved in at our institution • CCPH tool had less utility but a modified version of it could be helpful in future plans for moving forward • The CE task force has set strategic goals to further CE efforts, partially based on the results from this process • The results will help to identify priority areas to focus on and develop strategies to address |

Acknowledgements:

The authors wish to thank Community-Campus Partnerships for Health for consultation and permission to adapt the Self-Assessment methodology, recognize the University of Rochester Medical Center’s previous work in developing the preliminary use of the Framework, and acknowledge Kathleen Holt, PhD and Ann Dozier, PhD for their editorial assistance.

Funding/Support: The project described in this publication was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award Program from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, through the following awards: University of Rochester CTSA award number UL1 TR000042, University at Buffalo CTSA award number 1UL1 TR00141201, Columbia University CTSA award number UL1 TR000040, Medical College of Wisconsin CTSA award number 8UL1 TR000055, University of Wisconsin – Madison CTSA award number UL1 TR000427, Stanford University School of Medicine CTSA award number UL1 TR001085, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences CTSA award number UL1 TR000039, and University of Minnesota CTSA award number UL1 TR0000114. Additionally, this project was supported by these additional awards: University of Wisconsin – Madison award P60MD003428 from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities Center for Excellence, Columbia University award R25GM062454 from the National Institutes of Health, and the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin Research and Education Initiative Fund, a component of the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin endowment at the Medical College of Wisconsin. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin endowment.

Contributor Information

Karen Vitale, University of Rochester Medical Center, Center for Community Health, 46 Prince Street, Suite 1001, Rochester, NY 14607.

Gail L. Newton, University of Rochester Medical Center, Center for Community Health, 46 Prince Street, Suite 1001, Rochester, NY 14607, gail_newton@urmc.rochester.edu, (585)224-3057 (telephone), (585)442-3372 (fax)

Ana F. Abraido-Lanza, Columbia University, Department of Sociomedical Sciences, Mailman School of Public Health, 722 West 168th Street, 5th floor, New York, NY 10032, aabraido@columbia.edu, (212)305-1859 (telephone), (212)305-0315 (fax).

Alejandra N. Aguirre, Columbia University, Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, College of Physicians and Surgeons, 390 Fort Washington Avenue, Ground Floor, New York, NY 10033, ana2104@cumc.columbia.edu (646)697-2272 (telephone), No Fax.

Syed Ahmed, Medical College of Wisconsin, 8701 Watertown Plank Road, Milwaukee, WI 53226, sahmed@mcw.edu, (414)955-7657 (telephone), (414)955-6529 (fax.

Sarah L. Esmond, University of Wisconsin, School of Medicine and Public Health, Health Sciences Learning Center, 750 Highland Avenue, Rm 4241, Madison, WI 53705-2221, sesmond@wisc.edu, (608)263-9401 (telephone), (608)262-7864 (fax).

Jill Evans, Stanford University School of Medicine, Center for Population Health Sciences, 1070 Aratradero Road, Palo Alto, CA 94304, jille@stanford.edu, (650)736-8074 (telephone), No Fax.

Sherril B. Gelmon, Portland State University, OHSU & PSU School of Public Health, PO Box 751, Portland, OR 97207-0751, gelmons@pdx.edu, (503)725-3044 (telephone), (503)725-8250 (fax).

Camille Hart, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 W. Markham Street #820, Little Rock, AR 72205, CNHart@uams.edu, (501)454-1467 (telephone), (501)526-6620 (fax).

Deborah Hendricks, University of Minnesota, Clinical and Translational Science Institute, 717 Delaware Street S.E., Room 216, Minneapolis, MN 55414, dlhendri@umn.edu, (612)624-4247 (telephone), (612)625-2695 (fax).

Rhonda McClinton-Brown, Stanford University School of Medicine, Office of Community Engagement, Center for Population Health Sciences, 1070 Arastadero Road, Palo Alto, CA 94304, rhondam@stanford.edu, No Fax.

Sharon Neu Young, Medical College of Wisconsin, 8701 Watertown Plank Road, Milwaukee, WI 53226, sneuyoung@mcw.edu, (414)955-4439 (telephone), (414)955-6529 (fax).

M Kathryn Stewart, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 W. Markham Street, #820, Little Rock, AR 72205, stewartmaryk@uams.edu, (501)526-6625 (telephone), (501)526-6620 (fax).

Laurene M. Tumiel-Berhalter, University of Buffalo, Department of Family Medicine, 77 Goodell Street, Suite 220, Buffalo, NY 14203, tumiel@buffalo.edu, (716)816-7278 (telephone), (716)845-6899 (fax).

References

- Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Ahmed SM, Franco Z, Kissack A, Gabriel D, Hurd T, Ziegahn L, Bates N, Calhoun K, Carter-Edwards L, Corbie-Smith G, Eder M, Ferrans C, Hacker K, Rumala B, Strelnick A, & Wallerstein N (2014). Towards a unified taxonomy of health indicators: Academic health centers and communities working together to improve population health. Academic Medicine, 89(4), 564–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SM & Palermo A (2010). Community engagement in research: Frameworks for education and peer review. American Journal of Public Health, 100(8), 1380–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett SJ, Barnes T, & McIvor RA (2014). Integrating patients into meaningful real-world research. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 11(2 suppl), S112–S117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal D, & Meyer GS (1996). Academic health centers in a changing environment. Health A fairs (Millwood), 15,200–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1997). Principles of community engagement. First edition Atlanta (GA): Public Health Practice Program Office. [Google Scholar]

- Eder M, Carter-Edwards L, Hurd TC, Rumala BB, & Wallerstein N (2013). A logic model for community engagement within the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium: Can we measure what we model? Academic Medicine, 88: 1430 – 1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelmon S, Blanchard L, Ryan K, & Seifer SD (2012). Building capacity for community-engaged scholarship: Evaluation of the faculty development component of the faculty for the Engaged Campus Initiative. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement,16(1), 21–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gelmon S, Lederer M, Seifer SD, & Wong K (2009). Evaluating the accomplishments of the Community Engaged Scholarship for Health Collaborative. Metropolitan Universities Journal, 20, 22–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gelmon SB, Seifer SD, Kauper-Brown J, & Mikkelsen M (2005). Building capacity for community engagement: Institutional self-assessment. Retrieved from https://ccph.memberclicks.net/assets/Documents/FocusAreas/self-assessment.pdf

- Goedegebuure L, Van Der Lee JJ, & Meek VL (2006). In search of evidence: Measuring community engagement – a pilot study. EIDOS. http://e-publications.une.edu.au/1959.11/3964

- Gourevitch MN (2014). Population health and the academic medical center: The time is right. Academic Medicine, 89(4), 544–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, & Shannon S (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15,1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastor JA (2011). Accountable care organizations at academic medical centers. New England Journal of Medicine, 364, e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michener L, Cook J, Ahmed AM, Yonas M, Coyne-Beasley T, & Aguilar-Gaxiola S (2012). Aligning the goals of community-engaged research: Why and how academic medical centers can successfully engage with communities to improve health. Academic Medicine, 87, 285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio DM, Blank AE, Dozier A, Hites L, Gilliam VA, Hunt J, Rainwater J, & Trochim WM (2015) Developing common metrics for the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSAs): Lessons learned. Clinical and Translational Science Journal, (5), 451–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B (1973) Health services research: A working model. New England Journal of Medicine, 289, 132–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilagyi PG, Shone LP, Dozier AM, Newton GL, Green T, & Bennett NM (2014). Evaluating community engagement in an academic medical center. Academic Medicine, 89(4), 585–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westfall JM, Ingram B, Navarro D, Magee D Neibauer L, Zittleman L Fernald D, & Pace W (2012). Engaging communities in education and research: PBRNs, AHEC, and CTSA. Clinical and Translational Science, 5, 250–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]