Abstract

The current study identified subgroups of homeless youth and young adults that exhibited distinct co-occurring patterns of substance use and social stability (e.g., employment, school attendance, and housing), and evaluated the relative effectiveness of the Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA), Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET), and case management (CM) in interrupting substance use, and improving social stability. The differentiating effects of personal characteristics on the co-occurrence of substance use and social stability were also examined. Participants included 270 homeless youth and young adults who were randomly assigned to the three intervention conditions: CRA, n = 93, MET, n = 86, or CM, n = 91. Participants were assessed at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months post-baseline. A parallel process-latent class growth analysis identified four co-occurring patterns: low-stable substance use paired with low-increasing social stability, high-stable substance use paired with low-stable social stability, high-declining substance use paired with increasing social stability, and low-increasing substance use and high-stable social stability. Findings showed that CRA was superior in improving substance use and social stability simultaneously compared to MET and CM, and further, CM was more effective than MET. Personal factors including race, age, coping strategies, and behavior problems differentiated the co-occurring patterns of substance use and social stability. The findings underscore the significance in identifying subgroups of homeless youths that vary in problem severity in terms of their substance use and social stability, and offer evidence to help practitioners identify the most effective intervention that responds to the needs of homeless youth.

Keywords: randomized clinical trial, homeless youth, substance use, social stability

Research has documented high prevalence of substance use among homeless youth (Edidin, Ganim, Hunter, & Karnik, 2012). Substance use among homeless youth is associated with a wide range of physical and psychological problems such as engagement in risky sexual behaviors, high levels of psychological distress (Edidin et al., 2012), physical victimization, and involvement in illegal behaviors (Greene et al., 1997; Kipke et al., 1993). Additionally, substance use is one of the contributing factors for running away from home (Greene et al., 1997), and hinders homeless youth from transitioning off the streets and exiting homelessness (Kipke et al., 1993). Remaining homeless and living on the streets may, in turn, exacerbate problem behaviors and health concerns, and prevent homeless youth from reengaging in mainstream society. Thus, substance use treatment is usually a priority in homeless youth interventions (Slesnick, N., Guo, X., Brakenhoff, B., & Bantchevska, 2015). Compared to their housed peers, homeless youths are often disconnected from familial and institutional supports, leading to social isolation, and preventing homeless youth from engaging in substance use interventions (Slesnick et al., 2015). Given that homeless youth’s substance use is influenced by their larger social environment, assisting them to obtain employment, engage in education and become housed will likely stabilize their life and play a salient role in improving substance use outcomes.

Most studies focused on homeless youth’s substance use documents how the social environment influences substance use (Ferguson, Bender, & Thompson, 2014; Rice, Milburn, & Rotheram-Borus, 2007), but the effects of homeless youth’s substance use on their social environment are less understood. Indeed, research suggests that homeless youth’s substance use may play a role in shaping their social environment, particularly with reference to social stability represented as employment, attending school, and housing (Farabee, Shen, Hser, Grella, & Anglin, 2001; Zlotnick, Tam, & Robertson, 2003), such that substance use and social stability may co-occur over time. That is, decreased substance use is likely accompanied by increased social stability and vice visa. No prior studies have examined the co-occurrence of substance use and social stability over time. Thus, the first goal of the present study was to investigate the longitudinal co-occurring trajectory of substance use and social stability.

In addition to the limited understanding of the longitudinal co-occurring pattern of substance use and social stability among homeless youth, even less is known about how interventions influence this process. Given that improved substance use and social stability may reciprocally evoke positive change, specifically, as homeless youth’s substance use improves as a result of receiving intervention, their social stability is likely to improve, and vice versa, and the effects of intervention may sustain and extend beyond the treatment period. The second goal of the current the study was to examine the longitudinal effects of three empirically supported interventions, the Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA, Meyers & Smith, 1995), Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET, Miller & Rollnick, 2013), and case management (CM), on the co-occurrence of substance use and social stability.

Co-occurrence of social stability and substance use among homeless youth

Drawing on the ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) that problem behaviors are embedded in interrelated social contexts, homelessness is associated with disconnections from conventional environments including education, employment, and stable housing. Indeed, homelessness is an environment that encourages youth’s engagement in high risk substance use, sexual and criminal activities (Ferguson et al., 2014, Rice et al., 2007). Specifically, disconnection from conventional institutions such as school and employment reduces youths’ opportunities to connect to prosocial environments, and exacerbates substance use (Ferguson, Bender, Thompson, Maccio, & Pollio, 2012; Rice et al., 2007). Although many homeless youth have difficult school experiences and are not attending school (Haber and Toro, 2004), attending school increases homeless adolescents’ opportunity to connect with prosocial peers, which may protect them from substance use (Rice et al., 2007). Employment is another important path linking homeless youth to conventional and prosocial institutions (Ferguson et al., 2012), and likely contributes positively to homeless youth’s identity formation and social competence, while unemployment is associated with increased substance use and criminal activities (Ferguson et al., 2012).

In addition to emphasizing the social environment as shaping individual behaviors, the ecological perspective highlights individuals’ behaviors as influencing their social environment (McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988). Homeless youth’s substance use plays a salient role in shaping their social environment. For example, youth with substance use problems are unlikely to have gainful employment because they are more likely to turn to theft or dealing drugs in order to sustain their addiction (Farabee et al., 2001). A few studies highlight the association between substance use and housing stability among homeless populations. Those experiencing homelessness who also report no substance use problems more likely to engage with services and receive support from family and friends and to exit homelessness compared to those who report substance use problems (Bebout, Drake, Xie, McHugo, & Harris, 1997; Zlotnick et al., 2003). Thus, while substance use can estrange youth from normative environments, reduced substance use is likely to increase homeless youth’s opportunities to connect to prosocial environments and help stabilize their life. In sum, the studies reviewed above suggest substance use and social stability are likely to co-occur.

The present study

The current study used a randomized experimental design to examine the longitudinal co-occurrence of homeless youth’s substance use and social stability over time, and also tested the effectiveness of three theoretically distinct interventions, CRA (Meyers & Smith, 1995), MET (Miller & Rollnick, 2013), and CM. CRA (Meyers & Smith, 1995) is an operant-based behavioral intervention, with the goal to help youth and families restructure their environment so that positive behaviors are reinforced and maladaptive behaviors are discouraged. CRA has consistently shown great success in substance use interventions for adults (Higgins et al., 1995; Higgins, Wong, Badger, Ogden, & Dnatona, 2000), including homeless adults (Smith, Meyers, & Delaney, 1998). The Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (ACRA, Godley, Meyer et al, 2001), adapted from CRA, has been successfully used with adolescents diagnosed with cannabis abuse or dependence (Dennis et al., 2004). In the current study, CRA rather than ACRA was chosen because ACRA focuses on housed adolescents who have access to family, school and community resources that youth experiencing homelessness do not.

Motivational Interviewing (MI, Miller & Rollnick, 2002) assumes that the responsibility and capacity for change lies within the client. As an adaptation of MI, MET combines the clinical style of MI with personal feedback of assessment results, and has been well tested with both adults and adolescents. Yet, research findings with regard to the effectiveness of MET in treating substance use among homeless youth are mixed. For instance, Slesnick and colleagues (2013) found that MET was effective in reducing substance use among youth recruited from a runaway shelter, while Peterson and colleagues (2006) detected very few positive effects among a sample of street-recruited youth and young adults. Further, Baer et al. (2007) found little support for MET as a stand alone treatment for homeless youth in their efforts seeking to improve upon the findings of Peterson and colleagues. The variation of MET’s effectiveness may be due in part to sample differences. Street- and shelter-recruited youth differ in their levels of problem severity, with street-recruited youth generally showing more severe substance use and other psychosocial problems (Slesnick et al., 2015).

Case management is a standard approach used in community programs that serve homeless population (Zerger, 2002). However, other than Cauce et al. (1994) indicating the efficacy of case management in reducing behavior problems, depression symptoms, substance use, and homeless days for adolescents experiencing homelessness, limited research has tested the effectiveness of case management as a standalone intervention for homeless youth or adults. Case management does not provide targeted substance use treatment, but is identified as an evidence-based intervention by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

A person-centered approach (a group based approach; Nagin, 2005) was used to identify distinct co-occurring patterns of substance use and social stability, and compare the effectiveness of CRA, MET, and CM. Compared to a variable-centered approach that focuses on relationships between variables and assumes that the strength of relationships between variables applies equally to all participants, a person-centered approach focuses on relationships among individuals. This approach acknowledges that subgroups exist wherein individual response patterns are similar within a group and different between groups. Rather than a homogeneous group, subgroups of homeless youth with differing levels of problem severity and thus different intervention needs, exist (Slesnick et al., 2015). Consequently, youth may respond to the same intervention differently, and vary in their treatment outcomes. In the current study using group-based analysis, youths were classified into distinct subgroups based on their response patterns in terms of substance use and social stability, with youth within a group showing similar responses, and youth between groups differing in their responses. It was expected that subgroups with three distinct co-occurring patterns of substance use and social stability would be identified: (1) decreased substance use in co-occurrence with increased socially stability; (2) increased substance use in co-occurrence with decreased social stability; and (3) unchanged, stable substance use and social stability.

Following the identification of subgroups of substance use and social stability, the relevant effectiveness of CRA, MET, and CM was compared. Following a stage model of intervention development, this study is part of a stage II trial following a stage I trial that compared the effectiveness of CRA to treatment as usual (Slesnick et al., 2007). Findings from the stage 1 trial evidenced the efficacy of CRA in reducing substance use, depressive symptoms, and homelessness, compared to treatment as usual (Slesnick et al., 2007). Thus, in the stage II trial, it was expected that participants receiving CRA would show superior outcomes compared to those receiving CM and MET. The primary outcome paper for the stage II trial, comparing the effectiveness of CRA, MET, and CM on a wide variety of outcome variables (e.g., substance use, depressive symptoms, behavior problems) with a variable-centered approach, has been published elsewhere (Slesnick et al., 2015). With the variable-centered approach, superiority or inferiority of the three interventions in terms of substance use was not observed, i.e., all three treatments were equally effective in reducing substance use (Slesnick et al., 2015). As an extension of the primary outcome paper examining the univariate change of substance use with the conventional variable-centered approach, the current study is the first examination comparing the effectiveness of CRA, MET, and CM on the co-occurrence of substance use and social stability using a person-centered approach. It was expected that participants receiving CRA would show superior outcomes in the co-occurrence of substance use and social stability compared to CM and MET. Moreover, given that MET is an evidence-based intervention for substance use (Slesnick et al., 2015), it was further expected that MET would lead to superior outcomes compared to CM.

In addition to comparing the effectiveness of three treatments, this study sought to evaluate personal factors that differentiated the co-occurring patterns of substance use and social stability. This examination provides information with regard to personal characteristics that serve as promotive or risk factors for the co-occurring trajectory of substance use and social stability. Research indicates that age, sex, and race/ethnicity are associated with substance use and may influence individuals’ response to substance use interventions. For example, in a study examining the variation in mental health among homeless adolescents, (Cauce and colleagues 2000) reported that males and younger adolescents were likely to exhibit high rates of disruptive behavior disorders - a risk factor for substance use problems (Winters, 1999). Additionally, African American youth show elevated substance use in association with their experiences of racial discrimination (Gibbons et al., 2012), and report lower treatment completion and quicker relapse compared to White non-Hispanics (Milligan, Nich, & Carroll, 2004; Slesnick et al., 2013). Other variables, including sexual orientation, coping strategies, and delinquent behaviors are also associated youth’s substance use. In general, compared to their heterosexual peers, adolescents who are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT) exhibit higher rates of substance use (Cochran, Stewart, Ginzler, & Cauce, 2002). Additionally, LGBT homeless youth use highly addictive substances more frequently compared to heterosexual homeless youth (Cochran et al., 2002). The way that adolescents cope and respond to problems is also associated with their substance use (Wills, Sandy, Yaeger, Cleary, & Shinar, 2001). Generally, task-oriented coping, referring to taking an active and productive approach to respond to problems (Endler, & Parker, 1990b), is negatively associated with substance use (Wills et al., 2000). Delinquency is another factor that predicts initiation and progression of drug use in later years during adolescence (Mason, Hitchings, & Spoth, 2007). Although prior research has established the association between these personal factors noted above with substance use, it is not known how these variables are associated with the co-occurring pattern of substance use and social stability. As substance use and social stability are likely to co-occur over time, these personal factors were expected to influence social stability as well.

Methods

Participants

Homeless adolescents and young adults (n=270) were recruited from a homeless drop-in center in central Ohio. Youth were eligible to participate if they met the criteria of homelessness as defined by (McKinney-Vento Act 2002) as lacking a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence, or living in a welfare hotel, or place without regular sleeping accommodations, or living in a shared residence with other persons due to the loss of one’s housing or economic hardship. Eligible participants were between the ages of 14 to 20 years old and met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) for abuse or dependence for psychoactive substance use or alcohol disorder, as assessed by the Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule (CDIS, Shaffer, 1992). Table 1 presents a summary of the demographic characteristics of the current sample.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Variables | Total Sample (n=270) | CRA (n=93) | MET (n=86) | CM (n=91) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 128 (47.4%) | 43 (46.2%) | 38 (44.2%) | 47 (51.6%) | ||||

| Sexual orientation | ||||||||

| Straight | 209 (77.4%) | 72 (77.4%) | 70 (81.4%) | 67 (73.6%) | ||||

| LGBTQ | 51(18.9%) | 19 (20.4%) | 13 (15.1%) | 19 (20.9%) | ||||

| Race | ||||||||

| African American | 177 (65.5%) | 63 (67.7%) | 54 (62.8%) | 60 (65.9%) | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 53(19.6%) | 16 (17.2%) | 17 (19.8%) | 20 (22.0%) | ||||

| Other | 40(14.8%) | 14 (15.1%) | 15 (17.4%) | 11 (12.1%) | ||||

| Age | 18.74 (1.26) | 18.70 (1.34) | 18.69 (1.32) | 18.84 (1.11) | ||||

| History of physical or sexual abuse | ||||||||

| Physical abuse | 118 (43.7%) | 34 (36.6%) | 36 (41.9%) | 48(52.7%) | ||||

| Sexual abuse | 81 (30.0%) | 25 (26.9%) | 21 (24.4%) | 35 (38.5%) | ||||

| Number of days currently | 69.20 | 49.02 | 87.33 | 71.89 | ||||

| without shelter | (175.94) | (124.93) | (208.32) | (185.26) | ||||

Procedure

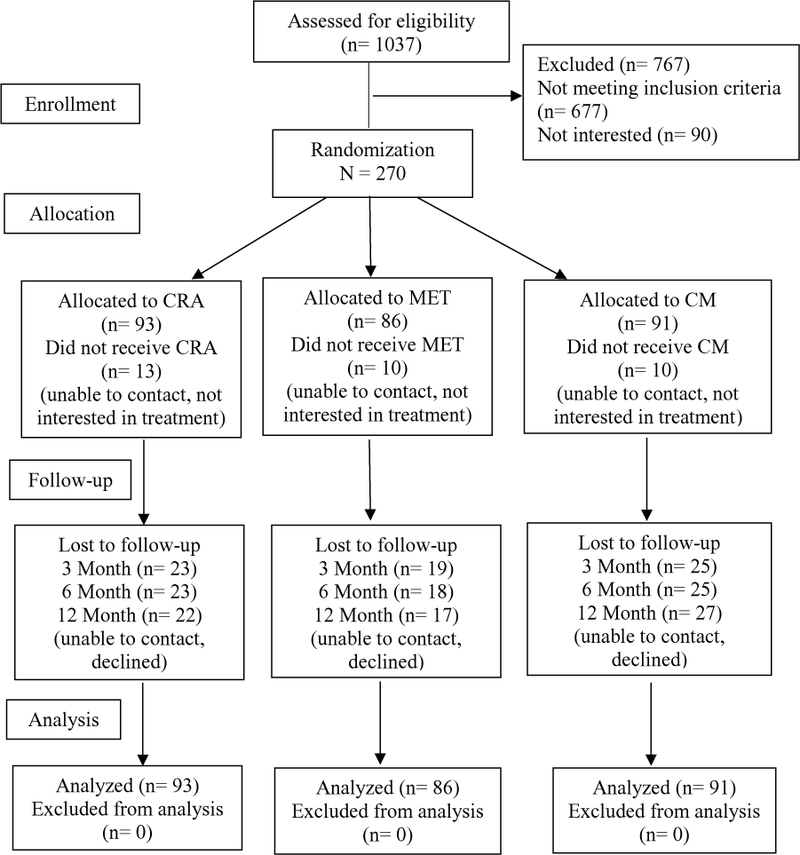

A research assistant (RA) engaged and screened homeless youth at the drop-in center. Written informed consent was obtained from eligible participants who were 18 years or older, and assent was obtained from youth under 18 years. Following the baseline assessment, participants were randomly assigned to CRA (N=93, 34.4%), MET (n=86, 31.9%), or CM (N=91, 33.7%). All treatment was completed by 6 months. Follow-up assessments were conducted at 3, 6, and 12 post-baseline. An URN randomization program that ensures baseline group equivalence was used to assign participants to each condition. The URN procedure retains random allocation and balances groups on a priori continuous or categorical variables. The variables used in the URN for this study included participants’ sex, age, race/ethnicity, childhood abuse history and sexual orientation. Participants were offered a $25 gift card at completion of the baseline assessment, a $50 gift card at each follow-up assessment, and a $5 gift card for each treatment session attended. All research procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at The Ohio State University. Figure 1 presents the study design and flow of participants.

Figure 1. CONSORT Flowchart.

Note. CRA=Community Reinforcement Approach; MET= Motivational Enhancement Therapy; CM= Case Management

Treatment conditions

CRA (Meyers & Smith, 1995) is an operant-based behavioral intervention with the goal to help youth and families restructure their environment to encourage positive behaviors and discourage maladaptive behaviors. In the current study, youth assigned to CRA received twelve 1-hour sessions as well as two 1-hour HIV prevention sessions. The core session topics include (1) a functional analysis of using behaviors, (2) refusal skills training, and (3) relapse prevention (4) job skills, (5) social skills training including communication and problem-solving skills, (6) social and recreational counseling, (7) anger management and affect regulation. The intervention is tailored to the unique needs and environmental context of individuals experiencing homelessness.

MET is an adaptation of Motivational interviewing (MI; Miller & Rollnick, 2013) that includes feedback. In this study, youth assigned to MET received two 1-hour MET sessions and two 1-hour HIV prevention sessions. Session 1 begins with open-ended MI, to establish therapeutic rapport and elicit client change talk in regard to substance use. Next, the client is given specific feedback about their substance use from the baseline assessment, within an MI counseling style. This period of feedback often continues into session 2. The therapist continues to focus on enhancing intrinsic motivation for change, transitioning as appropriate into the negotiation of a change plan and evoking commitment to the plan.

Youth assigned to CM received twelve 1-hour CM sessions and also two 1-hour HIV prevention sessions. CM seeks to link participants to resources within the community. The case manager starts to review six general areas with the participant to gather a history and picture of their current situation: (1) housing needs; (2) health/mental health care, including alcohol/drug use intervention; (3) food; (4) legal issues, (5) employment and (6) education. Then, the case manager helps the youth secure needed services and remains a support for the youth as he/she traverses the system of care. An initial intervention plan is developed with specific goals and objectives upon the completion of the review, and this plan is revisited and revised periodically with the youth.

MET and CRA therapists included master’s level counselors, marriage and family therapists or social workers who received training including manual review, didactic training and extensive role play, as well as weekly supervision throughout the study. In terms of CM, case managers were bachelor’s level social work students, and counseling was not provided, however, case managers received weekly supervision. Fidelity coding was only performed on CRA and MET. Fifty out of 457 (11%) CRA sessions and thirty-five out of 145 (24%) MET sessions were randomly selected and coded for adherence and competence. Adherence was operationalized as the average number of procedures used during a session with the use of more procedures indicating better adherence. CRA fidelity was rated over 9 procedures, and sample items were “linking positive rewards to non-substance using/non-problematic behavior,” and “explaining how substance using/problematic behavior leads to problems.” MET fidelity were also rated over 10 procedures, and sample items were “providing objective, unbiased information about client’s substance use,” and “ avoiding power struggles/rolling with resistance.” The average number of procedures used was 5.60 during a CRA session (SD=2.18, range 2.00–9.00) out of 9 potential procedures, and 10 during a MET session (SD = 0) out of 10 potential procedures. That is, good therapist adherence was found among CRA sessions while excellent adherence was found among MET sessions. As for competency, the CRA and MET procedures were rated on a scale from 1 (very poor) to 7 (exceptional). Therapist competence was 5.21 on average for CRA sessions (SD = 0.72, range 3.66–7.00) and 5.39 for MET sessions (SD = 0.38, range 4.22–6.00), both of which were in the “done well” range. Inter-rater reliability for procedure occurrence (adherence) of CRA was Kappa = 0.72, while the rater reliability of the CRA procedure rating (competence) was ICC = 0.81. Inter-rater reliability for procedure occurrence (adherence) of MET was Kappa = 0.98, while the rater reliability of the MET procedure rating (competence) was ICC= 0.77.

Measures

Substance use was measured using the Form-90 (Miller, 1996). The Form-90 is a semi-structured assessment that evaluates daily substance use for the past 90 days using a timeline follow-back approach. Test-retest reliability with kappas for different drug classes range from .74 to .95 (Tonigan, Miller, & Brown, 1997; Westerberg, Tonigan, & Miller, 1998). In the current study, the percentage of youth’s total days of drug use (except for the use of alcohol and tobacco) in the prior 90 days was evaluated at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months post-baseline.

Social stability at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months post-baseline was a composite variable assessed using the Form 90. The percent days of employment, school attendance, and housing days during the assessment period were added to yield a total score. The way social stability was calculated in the current study is similar to other research that examines homeless youth outcomes (Slesnick, Prestopnik, Meyers, & Glassman, 2007).

Baseline variables.

Baseline variables included participants’ age, sex (0 as male, 1 as female), sexual orientation (0 as straight, 1 as LGBTQ), race (African Americans were used the reference category), task-oriented coping, and delinquent behaviors. Task-oriented coping was measured using the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS; Endler & Parker, 1990a). The Cronbach’s alpha for the task-oriented coping subscale was .94. Delinquent behaviors were assessed using the Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach, 1991) and in the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha was .80.

Overview of Analyses

This study used an intent-to-treat design which consisted of the entire sample of 270 participants. First, a dual trajectory latent class growth analysis (LCGA) (Nagin, 2005) was performed with Mplus 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017) to identify the co-occurring patterns of substance use and social stability that were evaluated at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months post-baseline. This approach classified participants into distinct subgroups based on individuals’ treatment response in terms of substance use and social stability, with individuals within a group showing similar responses, and individuals between groups showing distinct responses (Jung & Wickrama, 2008; Lutz, Martinovich, & Howard, 1999). Second, after determining the optimal number of classes, a three-step approach (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014) was taken to examine the association between treatment condition and class membership, while controlling for the baseline individual factors.

Fit indices used to determine the optimal number of classes included: (a) Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and the sample size adjusted BIC (ABIC), of which a smaller value indicates a better model fit (Nylund, Asparouohov, & Muthén, 2007); (b) Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) that compares the fit between two nested models, with a significant p value indicating that a model with k classes fits better compared to a model with k-1 classes (Nylund et al., 2007); and (c) Entropy values close to 1 and latent class posterior probability close to 1 indicate good classification (Jung & Wickrama, 2008). Additionally, theoretical relevance in terms of the co-occurrence of substance use and social stability was also considered.

After the optimal number of classes was determined, treatment effects were examined following the three-step approach recommended by Asparouhov and Muthén (2014). This analysis is equivalent to a multinomial logistic regression, with class membership of substance use and social stability identified in the first step being the outcome variable. Treatment condition (CM as the reference group) and other control variables were added to the model as predictors. In this step, class membership was a latent categorical variable generated using the latent class posterior distribution, and was regressed on treatment conditions and other variables, taking into account the classification errors.

Results

Preliminary analysis

The descriptive statistics for substance use and social stability are presented in Table 2. The follow-up rates at 3, 6, and 12 months were 75%, 76% and 76% respectively. Little’s MCAR test showed that data were missing completely at random with χ2 (87) = 80.902, p = .664. Full information maximum likelihood was used to estimate missing data when performing the analyses. Participants in the three treatment conditions did not differ in age, sex, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity or childhood abuse history (p’s >.05). The univariate change of substance use and social stability using a variable-centered approach was examined. Substance use decreased over time (B = −5.60, SE = 1.02, p <.001), and social stability increased over time (B=18.45, SE=1.45, p <.001) in the whole sample. Moreover, a significant reduction in substance use was found in each treatment condition (BCRA = −7.61, SE = 1.78, p < .001; BMET = −5.04, SE = 1.82, p < .01; BCM = −4.09, SE = 1.77, p < .05), and improved social stability were also found in each treatment condition (BCRA=20.24, SE = 2.56, p <.001; BMET = 21.38, SE = 2.62, p <.001; BCM = 13.83, SE = 2.44, p <.001). Findings showed that there was significant variability in growth factors for both substance use (intercept variance = 647.98, p <.001; slope variance = 78.26, p <.05) and social stability (intercept variance = 668.39, p <.05; slope variance = 159.50, p <.05) in the whole sample. The significant individual variability in the intercept and slope factors substantiates the examination of subgroup heterogeneity of substance use and social stability using LCGA. The findings with regard to substance use were consistent with the findings from the primary outcome paper (Slesnick et al., 2015).

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations of substance use and social stability

| Variables | Total Sample | CRA | MET | CM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | |

| Substance usea | ||||||||

| Baseline | 270 | 61.48 (36.88) | 93 | 59.90 (38.89) | 86 | 68.16 (36.19) | 91 | 56.80 (34.85) |

| 3 mo follow-up | 202 | 49.63 (41.48) | 70 | 53.60 (40.76) | 66 | 45.67 (43.24) | 66 | 49.38 (40.66) |

| 6 mo follow-up | 202 | 43.53 (40.34) | 69 | 39.10 (38.83) | 68 | 48.88 (41.43) | 65 | 42.64 (40.74) |

| 12 mo follow-up | 197 | 45.32 (40.17) | 68 | 39.59 (39.86) | 67 | 50.72 (41.27) | 62 | 45.76 (39.10) |

| Social stabilityb | ||||||||

| Baseline | 270 | 46.61 (49.01) | 93 | 42.76 (49.80) | 86 | 38.55 (45.17) | 91 | 58.15 (50.04) |

| 3 mo follow-up | 202 | 72.63 (56.86) | 70 | 65.80 (54.58) | 66 | 75.83 (60.76) | 66 | 76.67 (55.38) |

| 6 mo follow-up | 202 | 93.82 (56.88) | 69 | 81.88 (60.51) | 68 | 99.10 (54.74) | 65 | 100.98 (53.83) |

| 12 mo follow-up | 203 | 102.37 (49.97) | 70 | 103.53 (51.90) | 69 | 101.90 (50.74) | 64 | 101.60 (47.70) |

Substance use represents percentage of total days of drug use (except for the use of alcohol and tobacco) in the prior 90 days. The mean score across four time points represents the average percent days of substance use. Higher scores represent higher frequency of substance use.

Social stability is a composite score including the percent days of employment, school attendance, and housing days. The mean score across four time points represents the average level of social stability. Higher scores represent greater levels of social stability.

Co-occurring trajectories of social stability and drug use

Compared to the two- (BIC= 18186.35; ABIC=18119.77) and three-class (BIC= 18129.16; ABIC=18040.38) solutions, the four-class solution (BIC= 18080.55; ABIC=17969.58) showed the smaller BIC and ABIC values, indicating that the four-class solution was better. Additionally, the BLRT value for the five-class solution was not significant, indicating that the five-class model was no better than the four-class model. The four- class model was considered optimal. The entropy value was .85. The posterior probabilities of class membership were .96, .90, .86 and .85 for the four groups, suggesting low classification errors.

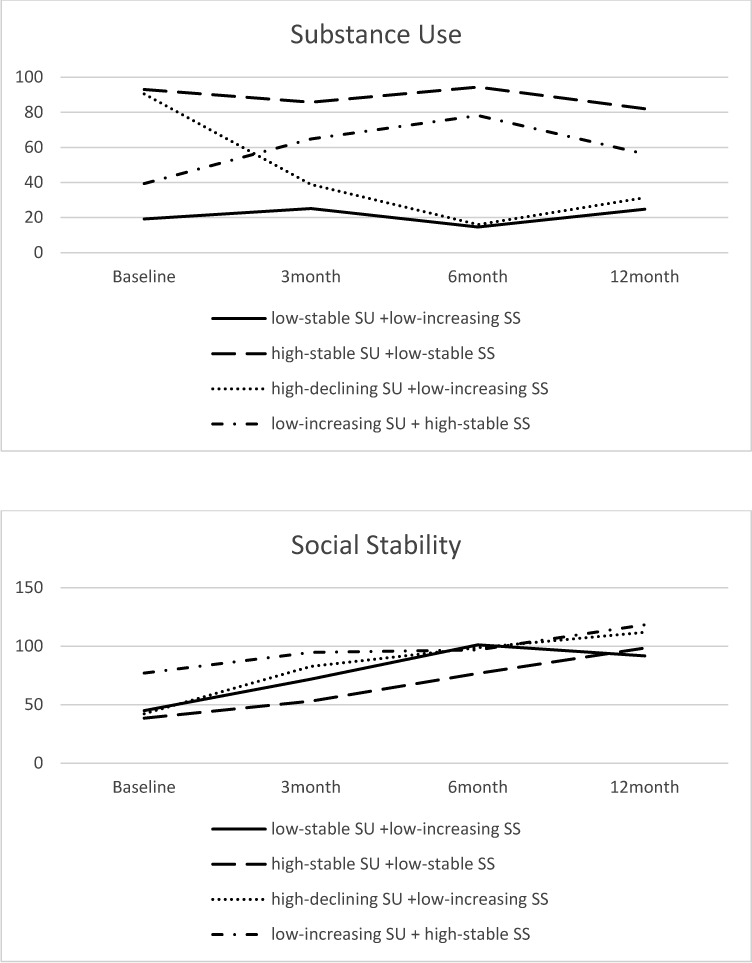

Figure 2 presents the four classes of substance use and social stability. The largest group, the low-stable substance use and low-increasing social stability group (labeled low-stable SU +low-increasing SS), accounted for 31.9% of the sample (n=86). Participants in this group exhibited the lowest initial level of substance use among the four subgroups, and this low level of substance use remained stable over time (intercept = 19.59, p < .001; linear slope = −5.30, p =0.299; quadratic slope = 2.02, p =0.275). Moreover, participants exhibited a low initial level of social stability, but social stability increased over time (intercept = 43.75, p < .001; linear slope = 43.39, p < .001; quadratic slope = −8.94, p < .01). The high-stable substance use and low-stable social stability group (labeled high-stable SU +low-stable SS) consisted of 25.2% of homeless youth (n=68). Participants in this group exhibited a low initial level of social stability and a high initial level of substance use. No improvement in either substance use or social stability was observed. Both substance use (intercept = 92.58, p < .001; linear slope = 4.20, p =0.313; quadratic slope = −2.26, p = 0.141) and social stability (intercept = 38.18, p < .001; linear slope = 14.74, p = 0.174; quadratic slope = 1.84, p =0.603) remained unchanged over time. The high-declining substance use and low-increasing social stability group (labeled high-declining SU +low-increasing SS), consisted of 29.6% of the sample (n=80). Similar to the group that showed no change in either substance use or social stability, participants in this group exhibited a low initial level of social stability and a high initial level of substance use. However, social stability increased (intercept = 42.87, p < .001; linear slope = 43.50, p < .001; quadratic slope = −6.92, p < .05) and substance use decreased (intercept = 90.60, p < .001; linear slope = −70.95, p < .001; quadratic slope = 16.98, p < .001) over time. The smallest group, the low-increasing substance use and high-stable social stability group (labeled low-increase SU +high-stable SS), consisted of 13.3% of the sample (n=36). Participants in this group exhibited a relatively high initial level of social stability and a moderate initial level of substance use. While social stability remained stable (intercept = 78.02, p <.001; linear slope = 10.26, p =0.525; quadratic slope = 0.90, p =0.860), substance use increased over time (intercept = 39.13, p < .001; linear slope = 43.91, p < .01; quadratic slope = −12.55, p < .05). Table 3 presents the results of LCGA modeling with regard to the mean level (intercept) for the intercept, linear slope and quadratic slope growth factors.

Figure 2.

Subgroup trajectories of homeless youth’s substance use and social stability

Table 3.

Results for Joint Trajectory Latent Class Models

| low-stable SU +low-increasing SS | high-stable SU +low-stable SS | high-declining SU +low-increasing SS | low-increasing SU +high-stable SS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | B(SE) | T | B(SE) | t | B(SE) | t | B(SE) | t |

| Substance use | ||||||||

| Intercept growth factor | ||||||||

| Intercept 1 | 9.59(2.97) | 6.61*** | 92.58(1.82) | 50.97*** | 90.60(2.08) | 43.65*** | 39.13(4.12) | 9.51*** |

| Slope growth factor | ||||||||

| Intercept | −5.30(5.10) | −1.04 | 4.20(4.16) | 1.01 | −70.95(3.71) | −19.15*** | 43.91(13.94) | 3.15** |

| Quadratic slope growth factor | ||||||||

| Intercept 2 | L02(1.85) | 1.09 | −2.26(1.54) | −1.47 | 16.98(1.48) | 11 48*** | −12.55(4.91) | −2.56* |

| Social stability | ||||||||

| Intercept growth factor | ||||||||

| Intercept 4 | 3.75(6.38) | 6.86*** | 38.18(5.33) | 7.16*** | 42.87(5.37) | 7.98*** | 78.02(14.60) | 5.34*** |

| Linear slope growth factor | ||||||||

| Intercept 4 | 3.39(8.64) | 5.02*** | 14.74(10.83) | 1.36 | 43.50(10.02) | 4.34*** | 10.26(16.13) | 0.64 |

| Quadratic slope growth factor | ||||||||

| Intercept | −8.94(2.72) | −3.29** | 1.84(3.54) | 0.52 | −6.92(3.11) | −2.23* | 0.90(5.11) | 0.18 |

Note. p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Generally, participants in the low-stable SU +low-increasing SS and high-declining SU +low-increasing SS groups exhibited better substance use and social stability compared to those in the high-stable SU +low-stable SS and low-increasing SU + high-stable SS groups. Furthermore, among youth who showed relatively better outcomes, although participants in the low-stable SU +low-increasing SS group did not show significant improvement in substance use, their initial levels of substance use were lowest among all four subgroups. The reason that substance use did not show any improvement in this group may be because it is more difficult to observe treatment effects with those who have low levels of symptoms, or participants’ substance use hit a low level already and it was hard to decline further due to floor effects. Among youth who showed relatively worse outcomes, although participants in the high-stable SU +low-stable SS group did not get worse in either substance use or social stability over time, their initial levels of substance use and social stability were relatively worse compared to the rest of the other groups.

Treatment effects

Table 4 presents the association between class membership, treatment condition and other baseline covariates. The class membership was an unordered categorical variable. The low-stable SU +low-increasing SS group was used as the reference class. CM was used as the reference treatment condition. Relative to the low-stable SU +low-increasing SS group, participation in the CRA condition was associated with lower likelihood to be in the low-increasing SU + high-stable SS group compared to receiving CM (OR = 0.174, p < .05, 95% CI: 0.033 – 0.908). That is, between CRA and CM, participants in the CRA condition showed superior outcomes, i.e., participants receiving CRA were more likely to show low initial levels of substance use and maintain the low levels of use, together with increasing social stability over time. The effects of CRA, MET, and CM were further compared with MET set as the reference condition. Relative to the low-stable SU +low-increasing SS group, those receiving CRA (OR = 0.311, p < .05, 95% CI: 0.117 – 0.826) or CM (OR = 0.225, p < .01, 95% CI: 0.075–0.676) were less likely to be the high-stable SU +low-stable SS group compared to MET. That is, CRA and CM were more effective compared to MET in terms of improving substance use and social stability. In other words, compared to those receiving CRA and CM, participants receiving MET were more likely to show high levels of substance use together with low levels of social stability, and show no improvement over time. In sum, CRA was the most effective intervention among the three approaches, and CM was more effective than MET.

Table 4.

Association between Trajectory Class Membership and Treatment Conditions and Baseline Covariates

| Variable | B | SE | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| high-stable SU +low-stable SS vs. low-stable SU +low-increasing SS | |||

| MET vs. CM | 1.49 | .56 | 2.66** |

| CRA vs. CM | .32 | .55 | .59 |

| Sexual orientation | 1.07 | .62 | 1.71 |

| White versus African American | −1.18 | .56 | −2.11* |

| Othera versus African American | −1.29 | .66 | −1.97* |

| Sex | .64 | .45 | 1.43 |

| Age | −.09 | .19 | −.48 |

| Task-oriented coping | −.02 | .02 | −1.04 |

| Delinquent behaviors | .14 | .05 | 2.88** |

| high-declining SU +low-increasing SS vs. low-stable SU +low-increasing SS | |||

| MET vs. CM | .38 | .47 | .82 |

| CRA vs. CM | −.25 | .44 | −.56 |

| Sexual orientation | .60 | .58 | 1.04 |

| White versus African American | −.58 | .49 | −1.19 |

| Othera versus African American | −0.10 | .50 | −.21 |

| Sex | .20 | .41 | .50 |

| Age | −.06 | .18 | −.32 |

| Task-oriented coping | −.03 | .01 | −1.81 |

| Delinquent behaviors | .03 | .04 | .78 |

| low-increasing SU +high-stable SS vs. low-stable SU +low-increasing SS | |||

| MET vs. CM | −.41 | .62 | −.67 |

| CRA vs. CM | −1.75 | .84 | −2.07* |

| Sexual orientation | 1.33 | .86 | 1.55 |

| White versus African American | −1.37 | .68 | −2.02* |

| Othera versus African American | −.99 | 1.03 | −.96 |

| Sex | .82 | .57 | 1.42 |

| Age | −.71 | .29 | −2.46* |

| Task-oriented coping | −.05 | .02 | −2.01* |

| Delinquent behaviors | .05 | .06 | .84 |

Note. CRA= Community Reinforcement Approach; MET= Motivational Enhancement Therapy; CM = case management.

Other represents non-White or African American.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Effects of baseline individual variables

As for the effects of baseline individual variables, race differentiated between the low-stable SU +low-increasing SS and high-stable SU +low-stable SS groups. Specifically, relative to the low-stable SU +low-increasing SS group, both Whites (B = − 1.175, p < .05, OR=0.309, 95% CI: 0.103 – 0.922) and other racial minorities (B = −1.287, p < .05, OR=0.276, 95% CI: 0.076 – 0.997) were less likely to be in the high-stable SU +low-stable SS group compared to African Americans. Additionally, race differentiated between the low-stable SU + low-increasing SS and low-increasing SU + high-stable SS groups, with Whites being less likely to be in the low-increasing SU + high-stable SS group (B=−1.365, p < .05, OR=0.255, 95% CI: 0.068 – 0.959). To sum, African Americans generally showed worse substance use and social stability outcomes compared to Whites and other ethnic groups.

Delinquency differentiated between the low-stable SU +low-increasing SS and high-stable SU +low-stable SS groups. Those that exhibited higher levels of delinquent behaviors were more likely to be the high-stable SU +low-stable SS group (B = 1.150, p < 0.01, OR = 1.15, 95% CI: 1.047 – 1.264). In sum, youth with higher levels of delinquent behaviors were more likely to show high initial substance use and low initial social stability and this trend continued over time without change.

Age and task-oriented coping differentiated between the low-stable SU + low-increasing SS and low-increasing SU + high-stable SS groups. Those who were younger (B = − 0.709, p<0.05, OR = 0.492, 95% CI: 0.279 – 0.867) or engaged in lower levels of task-oriented coping strategies (B = −0.045, p<0.05, OR = 0.956, 95% CI: 0.914 – 0.999) were more likely to in the low-increasing SU + high-stable SS group. In sum, homeless youth who were younger or engaged in less task-oriented coping were more prone to increased substance use.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to examine the effects of three viable interventions (CRA, MET, CM) on the co-occurring trajectory of homeless youths’ substance use and social stability. As expected, the current study identified subgroups exhibiting heterogeneous co-occurring patterns of substance use and social stability. The findings also provide evidence for the relative effectiveness of CRA, CM, and MET in improving substance use and social stability among homeless youth.

Building on theoretical perspectives informing the co-occurrence between substance use and social stability (Farabee et al., 200; Ferguson et al., 2014; Rice et al., 2007; Zlotnick et al., 2003), this is one of the first studies to identify distinct co-occurring patterns of substance use and social stability. Specifically, four subgroups were identified. Two subgroups showed relatively better outcomes, with one group exhibiting decreased substance use paired with increased social stability, and the other group exhibiting increased social stability while maintaining low stable substance use. In contrast, two groups showed relatively worse outcomes, with one group showing high substance use and low social stability initially with this pattern remaining unchanged, and the other group showing increased substance use paired with high stable social stability. Except for the subgroup that exhibited increased substance use paired with high stable social stability, our findings were generally consistent with the first hypothesis that highlights the reciprocally promotive effects of substance use and social stability on each other. The exception in terms of the co-occurrence between substance use and social stability, i.e., increased substance use paired with high stable social stability, may be due to the nature of social stability. Homeless youth may be able to maintain their employment, school attendance, and housing for a period of time once they secure them. As a result, social stability may have been unlikely to decline in our treatment follow-up, which is a relatively short period (one year). Observation beyond the treatment follow-up may reveal a better understanding of the longitudinal change of social stability.

In the primary paper that examined the effects of CRA, MET, and CM on univariate change trajectory of substance use, the three treatments were equally effective in reducing substance (Slesnick et al., 2015), although treatments differed in dosage, i.e., MET is less intensive than CRA and CM. Other research has similarly shown that MET appears to do as well as more intensive treatments for adolescent substance abusers (Becker & Curry, 2008; Dennis et al., 2004). The current study provides a more layered understanding of change in social stability along with substance use with a person-centered approach. The findings showed that different patterns of co-occurrence of substance use and social stability varied in their association with treatment conditions. Specifically, CRA resulted in superior outcomes in improving substance use and social stability compared to MET and CM. Specifically, participants in two subgroups who exhibited relatively worse substance use and social stability were less likely to have received CRA compared to either MET or CM. This finding is consistent with prior literature that has evidenced the effectiveness of CRA in improving substance use among homeless youth (Slesnick et al., 2015). Building upon the findings from prior studies, our findings also show the effectiveness of CRA in stabilizing homeless youth’s life. In general, CRA is powerful enough to interrupt substance use and concurrently improve homeless youth’s social stability. Further, CM was superior to MET. Although MET is an evidenced-based intervention for treating substance use, the effects of MET on social stability, and further, the co-occurrence of substance use and social stability had not been examined. The mechanism through which CRA, CM, and MET influences homeless youth’s substance use concurrently with social stability may help explain the superiority of CRA and CM over MET. Both CRA and CM focus on the environmental context of homeless youth. CRA is individually tailored to restructure the client’s environment in order to change their problematic behaviors. CM plays a role in reshaping the client’s environmental context through linking homeless youth to different community resources. Compared to CRA and CM, MET focuses on enhancing intrinsic motivation for change and assumes that clients take responsibility for changing their behaviors (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Clients’ environmental factors are not the intervention target of MET. Thus, when social stability was examined together with substance use, CRA and CM, which target environmental factors related to substance use, were more effective than MET. Together, these results suggest that when intervening with homeless youth, targeting both substance use and social stability is essential for longitudinal success, given the likely promotive effects substance use and social stability have on each other.

Our findings also showed that personal factors, including race, age, coping strategies, and behavior problems, differentiated severity of problems across the four subgroups. Compared to other racial groups, African American youth exhibited worse outcome in terms of substance use and social stability. Although no prior literature has examined how race influences co-occurrence of substance use and social stability, this finding is generally consistent with prior studies reporting worse substance use outcomes among African Americans (Gibbons et al., 2012). Research indicates that the experience of racial discrimination among African Americans is synchronously and prospectively associated with increased substance use either directly (Martin, Tuch, & Roman, 2003), or indirectly through transmitting mechanisms such as decreased effortful control (Gibbons et al., 2012) or stress (Guthrie, Young, Williams, Boyd, & Kintner, 2002). Compared to substance use, racial discrimination, in terms of social stability, is more pronounced. African Americans are generally more disadvantaged in securing social resources, likely because of racial discrimination, leading to restricted access to schooling, occupational opportunities and stable housing (Martin et al., 2003; Schulz et al., 2006; Martin et al., 2011). Examining substance use and social stability together highlights the multiple social barriers experienced by African American homeless youth.

Age was also a significant predictor of class membership. Younger youth were likely to show increased substance use, suggesting that younger youth may be more prone to the negative influence of homelessness in terms of their substance use compared to older youth. This finding is consistent with the literature indicating vulnerability of younger homeless youth in terms of problem behaviors including substance use (Cauce et al., 2000; Winters, 1999). Practitioners working with homeless youth should consider youth’s age and its related vulnerability to the negative influences of homelessness.

Additionally, our findings showed that delinquent behaviors were associated with worse substance use and social stability outcomes, supporting prior literature that shows the negative effects of delinquency on substance use, while adding to the existing literature about the negative influence of delinquency on social stability. Consistent with studies showing the positive effects of task-oriented coping on substance use (Wills et al., 2000), our findings showed that homeless youth who were more likely to engage in task-oriented coping were less likely to show increased substance use. Homeless young people tend to use alcohol and drugs as a way to cope with life stressors (Tyler & Johnson, 2006). As task-oriented coping helps reduce the negative effects of stressors through changing the stressful situation and buffering emotional distress (Unger et al., 1998), homeless youth engaging in task-oriented coping may be less likely to turn to alcohol and drugs as a way of coping with stressful situations. In sum, the effects of task-oriented coping and delinquent behaviors suggest potential risk and protective factors that can be addressed while intervening in substance use and social stability among homeless youth to enhance intervention effectiveness.

Limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, a convenience sample was used. The sample included youth from one drop in center in central Ohio. Moreover, youth participating in the treatment may be more motivated for change compared to those who refused to participate. Thus, these findings might not generalize to other sample of homeless youth. Finally, individual participants may be classified into subgroups due to ceiling or floor effects; however, it is beyond the capability of the analyses to decide who is classified into certain subgroups due to these effects. Consequently, the potential ceiling or floor effects may confound the effects of personal characteristics (e.g., age, race, task-oriented coping, delinquency) on class membership of substance use and social stability.

Despite these limitations, this is one of the first studies examining the co-occurrence of substance use and social stability. The co-occurring relationship between substance use and social stability underscores the importance of considering environmental factors when seeking to intervene in homeless youths’ substance use. Additionally, the diversity of co-occurring patterns highlights that homeless youths exhibit varying levels of problem severity (i.e., substance use and social stability), and thus have different intervention needs. The varied associations between different patterns of substance use, social stability and treatment condition suggest that interventions tackling environment factors, such as CRA and CM, are essential for maintaining the effects of the intervention in the long term. Moreover, the current study identified factors (i.e., race, age, coping, and delinquency) that characterize the co-occurring patterns of substance use and social stability, suggesting factors that can influence intervention process and outcomes. Practitioners need to consider these individual factors when working with homeless youth. Overall, the current study adds to a very small body of literature with regard to interventions for homeless youth by identifying distinct subpopulations, and providing evidence for the relative effectiveness of CRA, MET, and CM.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIDA grant R01 DA013549 awarded to the second author.

Contributor Information

Jing Zhang, Human Development and Family Studies, Kent State University

Natasha Slesnick, Department of Human Sciences, The Ohio State University

References

- Achenbach T (1991). Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4–18, YSR, and TRF profiles [Google Scholar]

- Burlington: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont. Asparouhov T, & Muthén B (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-Step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling, 21, 329–341. [Google Scholar]

- Baer J, Garrett S, Beadnell B, Wells E, & Peterson P (2007). Brief motivational intervention with homeless adolescents: Evaluating effects on substance use and service utilization. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21, 582–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebout RR, Drake RE, Xie H, McHugo GJ, & Harris M (1997). Housing status among formerly homeless dually diagnosed adults. Psychiatric Services, 48(7), 936–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SJ, & Curry JF (2008). Outpatient interventions for adolescent substance abuse: a quality of evidence review. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 76, 531–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Paradise M, Ginzler JA, Embry L, Morgan CJ, Lohr Y, & Theofelis J (2000). The characteristics and mental health of homeless adolescents: Age and gender differences. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 8, 230–239. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran BN, Stewart AJ, Ginzler JA, & Cauce AM (2002). Challenges faced by homeless sexual minorities: Comparison of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender homeless adolescents with their heterosexual counterparts. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 773–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Godley S, Diamond G, Tims F, Babor T, Donaldson J, et al. (2004). The cannabis youth treatment (CYT) study: Main findings from two randomized trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 27, 197–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edidin J, Ganim Z, Hunter S, & Karnik N (2012). The mental and physical health of homeless youth: A literature review. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 43, 354–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endler NS, & Parker JDA (1990a). Coping inventory for stressful situations (CISS): Manual. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Endler NS, & Parker JDA (1990b). Multidimensional assessment of coping: A critical evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 844–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farabee D, Shen H, Hser Y-I, Grella CE, & Anglin MD (2001). The effect of drug treatment on criminal behavior among adolescentsin DATOS-A. Journal of Adolescent Research, 16, 679–690. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson KM, Bender K, & Thompson SJ (2014). Social estrangement factors associated with income generation among homeless young adults in three US cities. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 5, 461–487. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson KM, Bender K, Thompson SJ, Maccio EM, & Pollio D (2012). Employment status and income generation among homeless young adults: Results from a five-city, mixed-methods study. Youth & Society, 44, 385–407. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, O’hara RE, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Weng CY, & Wills TA (2012). The erosive effects of racism: Reduced self-control mediates the relation between perceived racial discrimination and substance use in African American adolescents. Journal of personality and social psychology, 102, 1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene JM, Ennett ST, & Ringwalt CL (1997). Substance use among runaway and homeless youth in three national samples. American Journal of Public Health, 87, 229–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie BJ, Young AM, Williams DR, Boyd CJ, & Kintner EK (2002). African American girls’ smoking habits and day-to-day experiences with racial discrimination. Nursing Research, 51, 183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber MG, & Toro PA (2004). Homelessness among families, children, and adolescents: An ecological–developmental perspective. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 7, 123–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung T, & Wickrama KAS (2008). An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and personality psychology compass, 2, 302–317. [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Montgomery S, & MacKenzie RG (1993). Substance use among youth seen at a community-based health clinic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 14, 289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz W, Martinovich Z, & Howard KI (1999). Patient profiling: An application of random coefficient regression models to depicting the response of a patient to outpatient psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin MJ, McCarthy B, Conger RD, Gibbons FX, Simons RL, Cutrona CE, & Brody GH (2011). The enduring significance of racism: Discrimination and delinquency among Black American youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 662–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JK, Tuch SA, & Roman PM (2003). Problem drinking patterns among African Americans: the impacts of reports of discrimination, perceptions of prejudice, and” risky” coping strategies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44, 408–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act (2002). Re-authorized. 42 U.S.C. 11431 et seq 725. [Google Scholar]

- Mason WA, Hitchings JE, & Spoth RL (2007). Emergence of delinquency and depressed mood throughout adolescence as predictors of late adolescent problem substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21, 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers R, & Smith J (1995). Clinical guide to alcohol treatment: The community reinforcement approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR (1996). Form 90 a structured assessment interview for drinking and related problem behaviors Project MATCH Monograph Series, 5, U.S. Dept. of Health: Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Miller W, & Rollnick S (2013). Motivational Interviewing: Preparing people for change (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press [Google Scholar]

- Milligan C, Nich C,&Carroll K (2004). Ethnic differences in substance abuse treatment retention, compliance, and outcome from two clinical trials. Psychiatric Services, 55, 167–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, &Muthén BO (1998–2017). Mplus User’s Guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS, (2005). Group-based modelling of development Cambridge: Harvard Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouohov T, & Muthén BO (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A monte carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson P, Baer J, Wells E, Ginzler J, & Garrett S (2006). Short-term effects of a brief motivational intervention to reduce alcohol and drug risk among homeless adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20, 254–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice E, Milburn NG, & Rotheram-Borus MJ (2007). Pro-social and problematic social network influences on HIV/AIDS risk behaviours among newly homeless youth in Los Angeles. AIDS care, 19, 697–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D (1992). Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children −2.3 Version. NY: Columbia Univ. [Google Scholar]

- Slesnick N, Erdem G, Bartle-Haring S, & Brigham G (2013). Intervention with substance abusing runaway adolescents and their families: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81, 600–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slesnick N, Prestopnik JL, Meyers RJ, & Glassman M (2007). Treatment outcome for street-living, homeless youth. Addictive behaviors, 32, 1237–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Miller WR, & Brown JM (1997). The Reliability of Form 90: An instrument for assessing alcohol treatment outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 58, 358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, & Johnson KA (2006). Pathways in and out of substance use among homeless-emerging adults. Journal of adolescent research, 21, 133–157. [Google Scholar]

- Westerberg VS, Tonigan JS, & Miller WR (1998). Reliability of Form 90D: An instrument for quantifying drug use. Substance Abuse, 19, 179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger AM, Cleary SD, & Shinar O (2001). Coping dimensions, life stress, and adolescent substance use: A latent growth analysis. Journal of abnormal psychology, 110, 309–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters K (1999). Treating adolescents with substance use disorders: An overview of practice issues and treatment outcome. Substance Abuse, 20, 203–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerger S (2002). Substance abuse treatment: What works for homeless people? A review of the literature. Nashville, TN: National Health Care for the Homeless [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Tam T, & Robertson MJ (2003). Disaffiliation, substance use, and exiting homelessness. Substance Use & Misuse, 38(3–6), 577–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]