Abstract

Stem cells (SCs) govern tissue homeostasis and wound repair. They reside within niches, the special microenvironments within tissues that control SC lineage outputs. Upon injury or stress, new signals emanating from damaged tissue can divert nearby cells into adopting behaviours that are not part of their homeostatic repertoire. This behaviour, known as SC plasticity, typically resolves as wounds heal. However, in cancer, it can endure. Recent studies have yielded insights into the orchestrators of maintenance and lineage commitment for SCs belonging to three mammalian tissues: the haematopoietic system, the skin epithelium and the intestinal epithelium. We delineate the multifactorial determinants and general principles underlying the remarkable facets of SC plasticity, which lend promise for regenerative medicine and cancer therapeutics.

From totipotency of zygotes to pluripotency in the blas-tomere and multipotency, oligopotency or unipotency in mature tissues, self-renewing stem cells (SCs) become increasingly restricted in their cell fate options. In adult humans, the 50–70 billion cells lost daily in tissues from wear and tear are replenished through the action of lineage-restricted, resident SCs, which act as guardians of their designated lineages throughout life (BOX 1). This process of steady-state tissue maintenance is known as homeostasis and is one of the most crucial roles of a tissue SC.

Box 1 |. Stem cell: gold standard versus common properties.

Initially referred to by German biologist Ernst Haeckel as ‘Stammzelle’ in 1868, the term ‘stem cell’ (SC) was coined by Theodor Boveri and Valentin Haecker, who used it to describe cells giving rise to the germline, and by Artur Pappenheim and others, who used it to describe a common progenitor of the blood system (see commentary in REF. 193). In their 1961 seminal experiment, Till and McCulloch showed the existence of clonogenic bone marrow precursors, referred to as spleen colony-forming units (CFU‑S), that gave rise to macroscopic spleen colonies 11–14 days after injection into irradiated recipient mice2. The authors then proposed the defining property of SCs194: that at the single-cell level, an SC is capable of long-term self-renewal and multilineage differentiation, which has become the enduring definition of SCs that we use today. In contrast to the two gold standard features, there are several empirically observed characteristics frequently associated with SCs. First, given the importance of the SC niche, many fields began the search for SCs with defined anatomic locations, such as hair follicle SCs (HFSCs) in the bulge, intestinal SCs (ISCs) in the crypt, and muscle SCs (MuSC, the so‑called satellite cells) under the basal lamina of myofibres. However, niche locations are not static, nor are their residents. For example, trans-tissue migration is a common feature of many developing SCs, such as primordial germ cells, MuSCs and haematopoietic SCs (HSCs). Adult HSCs and their progenitors continue to travel among adult tissues195–197, and ectopic niches can be induced via various physiological stimuli, wounding or forced expression of stemness factors198,199. Second, the ability to retain cellular labels has been used to search for SCs200–202, which are often quiescent. While quiescence has been intimately linked to SC niche retention151,203–205 and stemness13,15,206,207, it is neither mandatory74,208–210 nor sufficient12,140 to define SCs. Third, asymmetric cell divisions are characteristic of many SC types58,211–216, but not all SC types exhibit such behaviour125,126. Among the cellular constituents that have been observed to partition asymmetrically, certain SCs are found to preferentially retain their old chromosome (the immortal strand hypothesis)217–219, whereas in many other cases such a phenotype has not been observed208,220. Finally, cell-surface markers are useful to prospectively enrich for SCs; however, these markers are insufficient to define SCs. Rather than being exclusive to SCs, many SC genes are in fact expressed in a gradient by SCs and multipotent progenitors57,139,221 and can sometimes be found in committed cells222. In addition, marker expression can often be misleading for the identification of putative SCs, particularly considering the widely observed plasticity under stress conditions, including cancer112,174,185,223–227.

In addition, tissue SCs must be equipped to rapidly bolster their regenerative response and restore tissue integrity when wounded, a process vital for the organ-ism. Even though regenerative capacity varies markedly across different tissues — for example, the skin and the heart represent the two extremes of high and low regeneration ability, respectively — their sense of urgency to repair wounds is conserved and has captured the molecular resourcefulness of nature. The outcome is a broadening of regenerative powers and lineage options compared with those seen under normal homeostasis. By enabling SCs to embark upon behaviours that are distinct from their normal patterns under homeostasis, a phenomenon termed cell plasticity, the SCs closest to a wound can participate in repairing it, thereby heightening the chances of tissue restoration and organism survival. However, as an essential survival mechanism during wound repair, plasticity is often hijacked by cancer, bypassing the need for actual injury in the presence of accumulating oncogenic mutations. Many parallels exist between wounds and cancer, with a few features distinguishing the two phenomena.

This Review discusses SC plasticity in the context of normal tissues as SCs transition from homeostasis to wound repair and tackles plasticity in malignant progression, a wound-healing process gone amok. We aim to contrast SC behaviours under steady state to those that are under stress. Meanwhile, we draw analogies across diverse stress conditions, including wounding, transplantation, culture and cancer, to illustrate how SC plasticity is conserved in certain aspects and distinct in others. We focus on plasticity in the context of SCs; however, the ability to remodel behaviour in response to changing environments may go beyond SCs, particularly in the context of cancer. Whenever suitable, we touch upon plasticity in other cells, including the fate-committed progenies and SC niches1, micro environments whose various constituents provide the instructive cues that have an impact on SC behaviour and fate decision. Our discussions centre on recent studies of three different mammalian tissues – the haematopoietic system, skin epithelium and intestinal epithelium – for which we know most about not only their SCs but also their niches. Whenever suitable, other SC models and species are introduced to further illustrate principles of SC behaviour and plasticity. We tackle several questions: how are SCs spatially and temporally coordinated within their niches? What is the molecular basis of the crosstalk between SCs and their niche components? What are the molecular components of a wound response that coax SCs to adopt new regenerative and differentiation routes that are closed to SCs in their native microenvironment? What are the boundaries of SC plasticity in an injury response, and how does the tissue return to normal homeostasis? Finally, what are the parallels between wound healing and cancer, and what are the molecular steps that lead to the derailment of SC behaviour during malignancy?

Heterogeneity under homeostasis

Adult SCs not only intimately associate with a diverse array of niche cell types within a given tissue but are also dynamically regulated by their niche signals. Therefore, heterogeneity of SCs needs to be considered in the con-text of both spatial differences and temporal changes. Below, we use three relatively well-characterized mammalian adult SC models to elaborate this idea of SC heterogeneity in space and time.

Haematopoietic stem cells and their niche.

The chase after Till and McCulloch’s famous spleen colony-forming units2 led to one of the most important discoveries in the SC field: the identification of self- renewing haemato poietic SCs (HSCs), which at near single-cell level are able to reconstitute the haematopoietic system of lethally irradiated mice3–5 (BOX 1). Probing deeper, fluorescence- activated cell sorting (FACS) was used to systematically purify and molecularly characterize bone marrow cells, which identified a long-term, repopulating subset of HSCs that could reconstitute all blood lineages6,7. Downstream of HSCs, haematopoiesis progresses via a stereotypic path to multipotent progenitors, common lymphoid progenitors and common myeloid progenitors and finally to all differentiated lymphoid and myeloid lin-eages8–10. It has been estimated that each HSC divides only about five times during the entire lifetime of a mouse11–13. Given that >30 billion haematopoietic cells per day are needed just to maintain human haematopoietic homeostasis, the majority of daily blood production has often been attributed to the fast-cycling multipotent progenitors rather than to their HSC parents14–18.

To preserve their stemness, HSCs, similar to other tissue SCs, are intimately associated with and functionally dependent on their SC niche. For many years, it was surmised that the HSC niche was the endosteal surface19, the cellular lining that separates bone from bone marrow and is composed of different cell types, including osteoblasts, osteoclasts and stromal fibroblasts. Live imaging showed that engrafted HSCs seem to home to the bone surface and were in close proximity to osteoblasts enmeshed in microvessels20,21. In recent years, however, attention has shifted to the sinusoidal22 and arteriolar23 endothelium as the niches for HSCs (FIG. 1a). Indeed, endothelial cells are crucial for HSC maintenance and formation24–27. Closely associated with the sinusoids, perivascular stromal cells express leptin receptor (LEPR) and C‑X‑C motif chemokine 12 (CXCL12; also known as SDF1) and are required for HSC maintenance and retention28–31. Upon activation, these stromal cells promote adipogenesis and HSC regeneration32,33. On the arterioles’ side, a group of perivascular cells expressing chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (CSPG4; also known as NG2) have been found to be essential for maintaining HSCs23. In addition, a population of stromal cells expressing nestin (NES) that is distinct from the LEPR-positive cells seems crucial for HSC maintenance34. The heterogeneity in niche cells, for example, the perivascular cells and the factors they secrete, suggests that distinct vascular niches exist within the bone marrow35. This finding is consistent with an earlier observation that HSCs and early lymphoid progenitors occupy distinct bone marrow niches25.

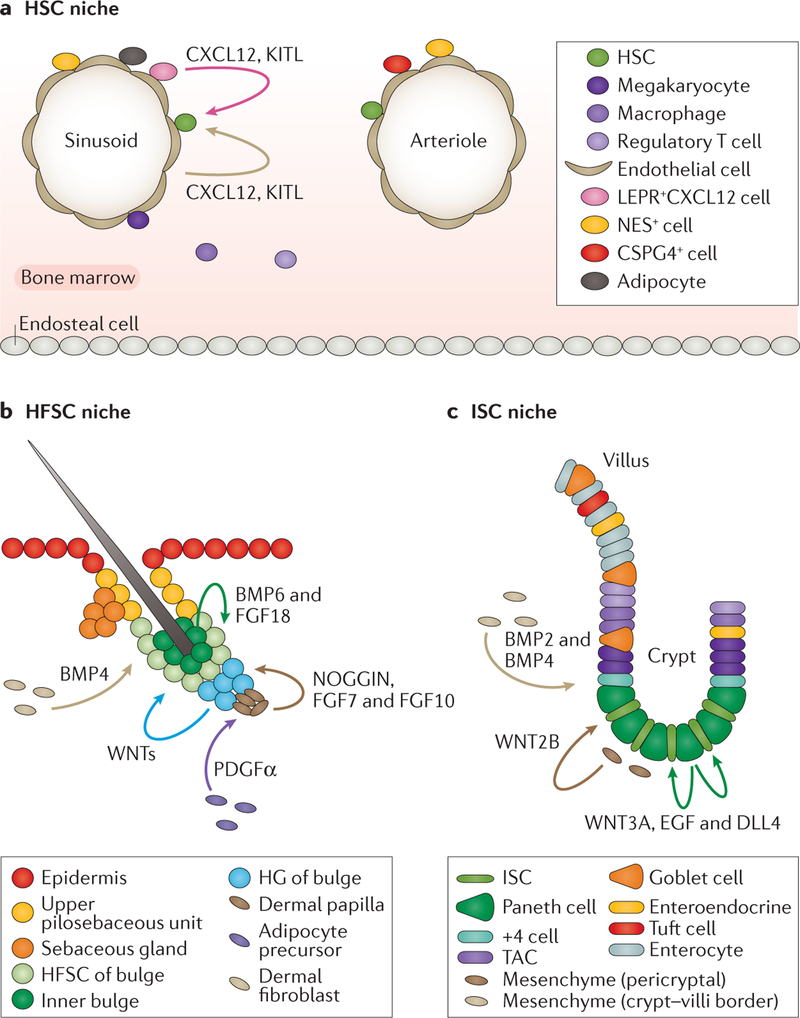

Figure 1 |. Stem cell heterogeneity in space and in time.

a | Perivascular niches described for adult haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the bone marrow. Niche cell types include endothelial cells and leptin receptor (LEPR)-positive cells at the sinusoids (which secrete C-X-C motif chemokine 12 (CXCL12) and stem cell factor/KIT ligand (KITL)), chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (CSPG4)-positive cells at the arterioles and nestin (NES)-expressing cells at both locations. In addition, adipocytes and HSC progenies (megakaryocytes, macrophages and regulatory T cells) are important for HSC expansion and maintenance. b | With each new adult hair cycle, the hair follicle and its SCs transition from a resting (telogen) to an activation (anagen) state. The interfollicular epidermis is maintained by its own basal SCs. Contiguous with the epidermis are hair follicles, whose stem cells (HFSCs) sit at the base of the resting follicle, a region called the bulge. HFSCs reside in the outermost bulge layer and are kept quiescent by bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) from dermal fibroblasts and BMP6 and fibroblast growth factor 18 (FGF18) from inner bulge cells. Basement membrane components, including laminin and collagen‑α1(XVII) chain (COL17A1) (not depicted), have also been reported to contribute to HFSC quiescence. HFSCs at the bulge base, the hair germ (HG), are in close proximity to a specialized mesenchymal stimulus known as the dermal papilla. Upon transition to the anagen state, inhibitory signals are replaced by activation signals, including WNTs from the dermis and/or the HG, NOGGIN (BMP inhibitor) and FGFs from the dermal papilla, facilitated by platelet-derived growth factor-α (PDGFα) from adipocyte precursors. c | In the small intestine, fast-cycling crypt base columnar (CBC) cells expressing high levels of leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein coupled receptor 5 (LGR5) are intestinal stem cells (ISCs). The quiescent +4 cells (counting from the base of the crypt) can also regenerate crypt and villi upon stress. ISCs are sandwiched between niche secretory Paneth cells, which secrete high levels of WNTs, epidermal growth factor (EGF) and the Notch ligand δ-like protein 4 (DLL4) to maintain self-renewal. WNTs may also originate from the pericryptal mesenchyme. Mesenchymal cells at the crypt–villus border secrete BMPs, which might be important to restrict WNT signalling and ISC proliferation. TAC, transit-amplifying cells.

As the HSC niche within the bone marrow continues to take shape, these studies — along with recent multi-colour and in vivo barcoding lineage tracing16,18,36,37 — collectively point to the view that molecular diversity in bone marrow niches may have an impact on the behaviour of its HSC residents, which could bias them towards distinct lineages before they enter the circulation (BOX 2). A number of questions remain to be addressed. What are the spatial and temporal relationships between the two niches? Does each niche know the status of the other, and if so, how is such crosstalk achieved? If molecular heterogeneity in HSCs exists and is compartmentalized in niches, then how does it affect functional lineage output?

Box 2 |. The long-sought haematopoietic stem cell heterogeneity.

When the ancestral form of haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), termed spleen colony-forming unit (CFU‑S), was discovered, Till and McCulloch observed wide variability in their colony formation and self-renewal efficiencies228 and proposed a stochastic model in which the outcome of each individual HSC is random and governed by probabilistic elements.

Although intriguing, a key issue of the model at the time was the impurity of these CFU‑Ss, which included not only HSCs but also progenitors229. Indeed, upon fractionation using cell-surface markers, it is possible to drastically enrich for long-term engraftment clones (mouse HSCs represent 0.05% of the adult bone marrow)7, suggesting that the fate of purified HSCs is deterministic. With various marker combinations, long-term (LT)-HSCs can be deterministically separated from short-term (ST)-HSCs7,230 and committed progenitors6,231. Collectively, mouse LT‑HSCs successfully engraft and undergo self-renewal in recipient mice at a rate of 14–47%22,232–238. Purified HSCs exhibit much less, yet still considerable, variability in engraftment efficiency18,237,239. Suboptimal conditions in transplantation assays might contribute to the observed engraftment inconsistency17.

In humans, severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)-repopulating cells (SRCs) compose 0.003% of cord blood and can be enriched with surface markers up to 25–31%240. Compared with the downstream committed short-term SRCs, which have a more rigid and predictable output, long-term SRCs exhibit stochastically variable repopulation and self-renewal activities in engraftments240. This observation argues against intrinsically distinct SC classes and instead fits a clonal maintenance model, which postulates an early phase of clonal fluctuations as a natural consequence of an expanding pool of HSCs, followed by a later phase of stable haematopoietic engraftments by a small number of HSC clones241. This model is analogous to the phenomenon of radioactive decay, which is a stochastic process at the level of single atoms — meaning that it is impossible to predict when a particular atom will decay — whereas the decay rate for a collection of atoms can be defined. Accordingly, despite HSCs behaving in a highly ordered and predictable way at the population level, the fate of an individual HSC is uncertain and random.

As thoughts on the stochastic versus deterministic heterogeneity of HSCs continue to evolve, recent attention has shifted to the heterogeneity of the HSC niche. With the prevalent notion that HSCs and progenitors manifest lineage bias36,242–246 and functional heterogeneity247–251, the ever more exciting question becomes whether and how niche differences contribute to such functional heterogeneity in vivo.

Intriguingly, progenies of HSCs themselves, such as regulatory T cells38, macrophages39–41 and megakaryo-cytes42,43, have been implicated in providing feedback and regulating HSC behaviours. These feedback loops could also contribute to spatial and temporal HSC heterogeneity and downstream lineage bias.

Skin epithelial stem cells.

In the skin epithelium, niche diversity clearly has an impact on both SC gene expression and functional output (reviewed in REF. 44). The stratified epidermis (often referred to as interfollicular epidermis) possesses an inner layer of proliferative basal SCs (keratinocytes), which is separated from the under-lying dermis by a basement membrane. When basal cells detach (delaminate), they cease proliferating and embark upon an upward path of differentiation, generating the skin barrier that excludes harmful microorganisms and retains body fluids. In transit, the differentiating cells undergo a programmed series of molecular changes that culminate in the production of dead squames, which are sloughed from the skin surface. In mice, this process takes approximately 2 weeks, resulting in constant rejuvenation of the skin barrier.

Contiguous with the epidermis are hair follicles (FIG. 1b), which are encased by the basement membrane that demarks the epithelial–mesenchymal border. The upper portion of the hair follicle, which includes the orifice and sebaceous glands, undergoes frequent turnover governed by multiple resident SC pools, each responsible for maintaining homeostasis of their nearby territory45–49. SCs of the interfollicular epidermis and upper hair follicle above the sebaceous glands have been recently reviewed elsewhere44,50,51.

Below the sebaceous glands is an anatomical structure known as the bulge, which consists of a single layer of SCs attached to the basement membrane and an inner layer of cells able to adhere to the hair during the resting phase of the follicle. Confirming their location and SC status, an individual colony can be cultured from a single bulge cell that expresses high levels of integrins and can be passaged long-term. Most importantly, upon engraftment, the cells from such a colony can generate hair follicles, epidermis and sebaceous glands upon engraftment52,53. Comparative lineage tracing with additional bulge markers, for example, leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein coupled receptor 5 (LGR5) or keratin type I cytoskeletal 15 (KRT15), has added further corroborative evidence that the integrin-rich bulge cells are hair follicle SCs (HFSCs)54–56.

In contrast to other skin epithelial compartments, the lower portion of hair follicles undergoes cyclical bouts of regeneration fuelled by HFSCs, which is a natural part of their homeostasis. During the resting phase (telogen), which is synchronous in mice and can last months, bulge HFSCs are quiescent. During this time, quiescent HFSCs at the bulge base (the hair germ) are in close proximity to a specialized mesenchymal stimulus known as the der-mal papilla. Molecular crosstalk between the HFSCs and the dermal papilla poises the hair germ in a primed state, such that it is activated at the start of a new regenerative phase (anagen)57.

Recent single-cell analyses reveal that in contrast to the bulge HFSCs, which are molecularly homogeneous, hair germ SCs display heterogeneity based on their spatial proximity to the dermal papilla58. HFSCs in the bulge and hair germ that are more distant from the der-mal papilla give rise to the outer root sheath, which is contiguous with the bulge and forms the outermost epithelial layer of the downwards-growing anagen follicle. SCs closest to the dermal papilla begin as multipotent progenitors that become more restricted in their fates as the hair follicle grows. The mature hair follicle consists of seven distinct lineages of short-lived transit-amplifying cells that divide several times and then terminally differentiate upward to form the hair and its channel.

At the end of the active growth phase, hair follicles enter a destructive phase (catagen), in which two-thirds of the newly generated hair follicle undergoes apoptosis. The upper and middle outer root sheath cells form a new bulge and hair germ from HFSCs that remain associated with the dermal papilla and will fuel the next round of the hair cycle59. The inner layer of the bulge consists of terminally differentiated late-stage progeny that transmit inhibitory cues, such as bone morphogenetic protein 6 (BMP6) and fibroblast growth factor 18 (FGF18), to the HFSCs to help maintain quiescence56. In this regard, HFSCs resemble HSCs, that is, their progeny form a negative feedback loop to restrict SC activity. Interestingly, during the anagen phase, HFSCs also rely on a positive feedforward loop, whereby their early progeny produce a positive factor, sonic hedgehog protein (SHH), that stimulates not only dermal papilla but also bulge HFSCs. Such stimulation lasts until the progeny and the dermal papilla have moved downward and are no longer in sufficiently close proximity to bulge HFSCs59. These two examples — one late and negative in the hair cycle and the other early and positive — add to the emerging paradigm that SC progenies can play a profound role in influencing the behaviour of their parents.

At all stages, contact with the basement mem-brane seems to be a universal feature of epidermal SCs (EpdSCs) and HFSCs, as well as their progenitors. Although little is known about basement membrane diversity, it is known to be rich in extracellular matrix proteins, proteoglycans and growth factors, and in this regard, it is likely a critical component of epithelial SC and progenitor niches. Extracellular matrix components of the basement membrane have been shown to participate in maintaining HFSC quiescence60,61. Many of these basement membrane components are made by keratinocytes and hence could add to the autoregulatory circuitry that guides SC activity.

Although autocrine factors play a major part in governing the behaviour of HFSCs, as shown above, paracrine signals from the niche are also crucial. Waves of BMPs, which are secreted by dermal fibroblasts, have been implicated in controlling the synchrony of the quiescent state of HFSCs62. More locally, the dermal papilla has long been known to be a transmitter of hair growth stimulatory factors (for example, BMP inhibitors, FGF7 and FGF10) important for activating hair germ SCs59,63 and essential for hair follicle regeneration64–66. Activating signals for dermal papilla and hair growth have been shown to come from nearby platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-secreting adipocyte precursor cells67.

Whereas the decline of BMP signalling is needed to allow proliferation, a concomitant rise in WNT signal-ling is essential to initiate hair follicle regeneration and lineage commitment57. Exactly where the WNT ligand originates is still unclear, but evidence suggests that it could come either from the hair germ itself57 or the der-mal fibroblasts62,68. Interestingly, epithelial WNTs seem to be essential, as hair regeneration is compromised when all WNT ligands are ablated from the SCs69.

Additionally, although the precise nature of their crosstalk is still unfolding, resident macrophages70 and regulatory T cells71 influence HFSC activity. Four types of sensory neurons wrap around the upper bulge and also seem to have a role in communicating with HFSCs45,72. As the stimuli, sources and contexts for HFSC communication with other cell types continue to emerge, the constitution of the niche and its dazzling constellation of signalling exchanges with the SCs should yield new insights into how tissue integrity is sensed and how SC behaviour is regulated to ensure precise spatial and temporal lineage output.

Intestinal epithelial stem cells.

Similar to the epidermis, the small intestine represents another continually self-renewing epithelial tissue; however, it takes only 3–5 days for a SC at the crypt base to generate transit-amplifying cells, which progressively differentiate into actin-rich, nutrient-adsorbing villi and become extruded into the intestinal tract. Intestinal SCs (ISCs) were first described on the basis of their relatively undifferentiated columnar morphology73 (FIG. 1c). Sandwiched between immune responsive Paneth cells at the crypt base, ISCs are marked by LGR5 and divide every 24 hours74. Lineage tracing further revealed that ISCs can give rise to all functional cells of the villi (enterocytes, tuft cells, goblet cells and enteroendocrine cells)74. Unequivocally establishing their stem-ness, a single purified LGR5-positive cell can generate a functional intestinal organoid, replete with all lineages of the endogenous epithelium, including Paneth cells74,75. Remarkably, whether initiated from mouse ISCs75 or from human induced pluripotent SCs (iPSCs) differentiated into ISCs76, these intestinal organoids can be maintained and propagated indefinitely in culture, a property analogous to that of human EpdSCs77. Although the continual self-renewing and tissue turnover properties of ISCs resemble those of EpdSCs, other homeostatic properties, such as the ability to generate multiple lineages, are more similar to those of HFSCs.

Paneth cells constitute an important component of the ISC niche. It has been suggested that by sensing nutrient availability, Paneth cells function in fine-tuning the size of the ISC compartment78. These cells also produce three important factors that are essential for ISC survival: WNT3A, epidermal growth factor (EGF) and the Notch ligand δ-like protein 4 (DLL4)79–85.

WNT signalling is particularly important for ISC maintenance and intestinal function86–90. The source of WNT proteins seems to extend beyond Paneth cells to pericryptal mesenchymal cells91. Indeed, crypts tolerate Paneth cell loss in vivo but fail to grow ex vivo without exogenous WNT92–94, implying that the underlying stromal cells are an important niche component. Furthermore, loss of epithelial WNTs can be compensated by WNTs emanating from the stroma niche95. This contrasts with the hair follicle, where epithelial WNTs seem to be essential69. Another important stromal ligand is a group of R-spondin proteins, which act on ISC-expressed LGR5 to amplify WNT signalling75,88,96–98 and to maintain a short-range gradient of this powerful morphogen99. Finally, mesenchymal cells at the crypt–villus border secrete BMPs100,101, which might be important to restrict WNT signalling and ISC proliferation, analogous to the hair follicle56,62,102.

Regulation of stem cell behaviour on chromatin.

Advances in high-throughput sequencing technology have made it possible to map the genome-wide transcriptional and chromatin landscapes of SCs and their progenies, resulting in new insights into their states and identities. It is becoming increasingly clear that chromatin dynamics underlie the lineage choices that SCs make in response to niche changes in space and in time.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP–seq) studies on cultured (embryonic) SCs gave the first indications that master transcription factors of pluripotency bind cooperatively to large open chromatin domains, which are often referred to as super-enhancers103 or stretch-enhancers104 (reviewed in REF. 105). These robust enhancers are marked by high levels of acetylated histone 3 lysine 27 (H3K27) and bound by the Mediator complex, which is involved in bringing enhancers and promoters together to facilitate active gene transcription. Although super-enhancers govern expression of only ~5–10% of the genes expressed by a particular SC103, this subset includes genes encoding key stem-ness and cell identity factors, including master transcription factors, which in turn control the expression of cell identity genes, as well as their own genes. Of note, these enhancer regions are frequently associated with human disease risk loci104,106–109.

Given the importance of niche-SC interactions, a closer look at niche changes in space and time is predicated upon the direct interrogation of chromatin in vivo in the native state of the SC. The abundance and synchrony of hair follicles110 and high-sensitivity chromatin analysis (for example, see REF. 111) have allowed such insights, thereby extending this paradigm to adult SCs residing in their native niches.

The chromatin regulators and transcription factors bind to specific densely clustered regions (epicentres) within super-enhancers, which renders these shorter regulatory elements particularly sensitive to changes in the local microenvironment103,110. This configuration endows SCs with the ability to rapidly switch fate in response to niche alternations110. The ability of epicentres to drive cell identity and state-specific gene expression has been functionally demonstrated with reporter assays in vivo58,110,112–114. For instance, HFSC epicentres drive reporter gene expression exclusively within the single layer of quiescent bulge HFSCs, but upon WNT activation and BMP inhibition, such epicentres become silenced and a new set of super-enhancers and their epicentres become activated in lineage-committed progenitors, driving the expression of lineage-specific genes58,115.

The ability of lineage master transcription factors to guide WNT and BMP signalling effectors (β-catenin and TCF transcription factors, and SMAD family members 1/5, respectively) onto chromatin to genes controlling cell-type-specific lineage programmes was first recognized for haematopoietic lineages116. Similarly, in skin epithelial SCs in vivo, it is notable that within the HFSC regulatory elements are binding sites not only for master transcription factors such as SRY-related transcription factor SOX9 and LIM/homeobox protein LHX2, but also for the WNT-β-catenin effectors TCF3 (also known as TCF7L1) and TCF4 (also known as TCF7L2) and downstream BMP-regulated transcription factors SMAD1 (also known as MAD homologue 1)117 and nuclear factor of activated T cells, cytoplasmic 1 (NFATc1)110,118. While much research is still needed, these studies collectively provide insights into how SCs perceive their niche microenvironment and how they change their chromatin landscape in response to new signals. In this regard, it is notable that most, if not all, signalling pathways are typified by downstream transcriptional effectors.

Stem cell plasticity under stress

Having explored SC behaviours under homeostasis and their spatial and temporal regulations, we now turn to stress conditions that expose the remarkable plasticity of SCs. Below, we discuss several recent studies that have begun to shed light on how SC behaviour deviates from steady state in order to cope with stress and ensure organismal fitness and survival.

Unleashed fates upon niche vacancy.

When SCs are lost, surrounding SC progenies or SCs from a more distant niche can often substitute and restore homeostasis. This principle of SC plasticity has perhaps been best illustrated using laser ablation experiments. For instance, when bulge HFSCs are ablated, creating unoccupied sites within the niche, cells from the underlying hair germ will migrate to fill niche vacancies created in the lower bulge, whereas cells above the bulge will migrate down to fill vacancies in the upper bulge64,119,120 (FIG. 2Aa). These studies clearly show that the key stimulus for SC plasticity is rooted in the creation of niche vacancies. This finding is consistent with the classic notion in the haematopoiesis field that host bone marrow needs to be ablated to empty the niche, in order for bone marrow transplants to survive (FIG. 2Ab). Such plasticity seems to have ancient roots, as depletion of Drosophila melanogaster germline SCs can promote the reversal of committed progenitors121–123. Consistently upon niche vacancy, an SC descendant can migrate over a distance and actively home to an appropriate niche to mediate replenishment124.

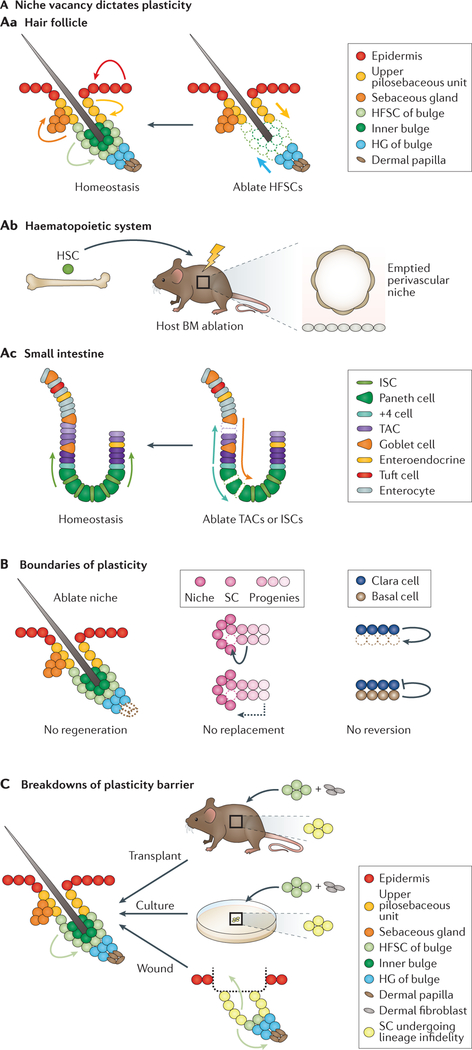

Figure 2 |. Stem cell plasticity under stress.

A | In the hair follicle (part Aa), under homeostasis, each stem cell (SC) compartment is maintained by corresponding resident SCs (curved arrows). By contrast, ablated bulge cells (emptied circles) are replenished by both the upper pilosebaceous unit and the hair germ (HG) (straight arrows). In the haematopoietic system (part Ab), ablating host bone marrow haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) allows transplanted HSCs (green cell) to successfully engraft. In the small intestine (part Ac), while intestinal stem cells (ISCs) maintain homeostatic turnover, quiescent +4 cells, secretory progenitors (curved arrows), enteroendocrine cells and enterocytes are all competent to mediate repair upon irradiation damage (emptied circles). B | Plasticity has boundaries. When the dermal papilla of the murine hair follicle SC niche is ablated (emptied circles), hair regeneration is defective (left panel). In the Drosophila melanogaster gonad, SC progenies immediately juxtaposed to the niche are competent (curved arrows) to replace lost SCs (emptied circle), whereas cells just a short distance away do not participate in repair (dashed arrow) (middle panel). In the lung, feedback regulation from basal cells limits plasticity from Clara cells (right panel). C | SC plasticity is broadened upon transplantation and culturing and during wound repair. Hair follicle SCs (HFSCs) fuel hair regeneration under steady state but regenerate both hair follicle and epidermis upon transplantation and during wound repair. In culture, HFSCs also undergo lineage infidelity (yellow circles) and become epidermis-like, which can be resolved once they are grafted onto an immunosuppressed host, resulting in the regeneration of both interfollicular epidermis and hair follicles. BM, bone marrow; TAC, transit-amplifying cells.

The concept of niche vacancy similarly applies to the small intestine, albeit with a major difference (FIG. 2Ac). Under steady state, the crypt niche seems to be highly active. It has been suggested that 15 equipotent LGR5-positive ISCs of each crypt divide symmetrically every 24 hours. This yields LGR5-positive daughter cells that stochastically compete for crypt niche space, and hence the ones at the crypt base have the highest chance of being retained as ISCs75,125–127. Correspondingly, the ISCs closest to the crypt border have the greatest tendency to become committed and differentiate127. High tissue turnover rate and the constant need for niche replenishment drive ISCs to be active under steady state. In this regard, ISCs are more similar to EpdSCs than to HSCs and HFSCs (discussed below).

Interestingly, other intestinal cells exhibit plasticity in addition to ISCs; for example, crypt border cells (+4 cells), which are quiescent under steady state and express relatively low levels of LGR5, can repopulate lower crypt positions made vacant through the ablation of ISCs, which highly express LGR5 (REFS 128–135). Moreover, using lineage tracing with markers of more advanced lineage states, secretory cells136, enteroendocrine cells135 and absorptive cells137 have all been shown to possess at least some potential to restock crypts in which ISCs have been damaged or lost. A topic still under intensive investigation127,135,136,138–141, plasticity in the intestinal crypt, has been attributed to broadly permissive chromatin in the intestine142–144. Consistent with this notion, deleting proliferating ISCs does not affect short-term crypt maintenance131,132, presumably due to active repair by neighbouring epithelial cells, which otherwise would differentiate along one of the lineages afforded to the ISCs. That said, LGR5-positive cells seem to be required for maintaining crypt integrity long-term under conditions where the intestinal epithelium is severely damaged, for example, through gamma irradiation145, suggesting that context dependency is a crucial determinant in considering plasticity (BOX 3).

Box 3 |. Context dependency.

Because of cellular plasticity, the consequence of deleting quiescent stem cells (SCs) under steady state can be hardly noticeable until after a prolonged period17,59,201,252 or until additional stimuli forcibly activate quiescent SCs253. Similarly, consequences of perturbed master developmental signalling may be selectively revealed under certain contexts. For example, despite Notch and WNT being essential for haematopoietic SC (HSC) function, conditional deletion in vivo in HSCs of the relevant Notch receptor and ligand254 or the key mediator of WNT signalling β-catenin255,256 does not affect adult HSC maintenance. Similarly, in the hair follicle, β-catenin-deficient HFSCs remain viable257,258, even though WNT signalling is required for hair follicle regeneration. The picture changes when quiescent SCs are forcibly activated: when HFSCs lacking β-catenin are induced to undergo activation, lineage differentiation is skewed258.

Curiously, under oncogenic stress, β-catenin becomes essential to sustain leukaemia SCs of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML)259. So are the transcriptional co-activator YAP1 and WW domain-containing transcription regulator protein 1 (WWTR1; also known as TAZ), which are dispensable during intestinal homeostasis but become essential for crypt regeneration in culture and outgrowth of WNT-hyperactivated crypt90. While mechanistically revealing, such context dependency can also be exploited to find cancer vulnerability, that is, genes and pathways selectively required by cancerous but not normal SCs so that the latter would be spared in targeted cancer therapies. For example, lineage infidelity represents a key mechanism that SCs employ to cope with stress, distinct from a mere proliferative response, and offers a unique opportunity to dissect cancer-specific dependencies112.

Boundaries and breakdown of the plasticity barrier.

Even though SCs can exhibit remarkable plasticity under stress, they have their boundaries (FIG. 2B). In part, limitations of SC plasticity could be a reflection that certain niche components are much more resistant to fate changes. For example, when the hair follicle dermal papilla is ablated, its loss is not rescued by other dermal fibroblasts and, consequently, hair follicle regeneration grinds to a halt64,65. In D. melanogaster gonads, differences in cell adhesion, cellular growth rate and number of divisions downstream of germline SCs all contribute to the efficiency of replacement146. In studies of the lung epithelium, a single basal SC seems sufficient to restrain co-cultured secretory Clara cells from dedifferentiating147, raising the distinct possibility that basal SCs may emit some type of inhibitory signal that prevents neighbouring cells from reverting to a SC state.

In another interesting twist to SC plasticity, ablation of a myoepithelial cell of the sweat gland prompts rescue by a dividing neighbouring myoepithelial cell but not a luminal or ductal cell148. The converse is also true; that is, ablation of a luminal cell is rescued only by its own lineage148. Intriguingly, such boundaries can break down, as shown in transplantation experiments in which a purified myoepithelial cell upon engraftment into a cleared mammary fat pad could regenerate an entire sweat gland148. This observation is reminiscent of earlier studies on mammary glands, which found that myoepithelial cells adopt broadened fates upon engraftment149, and further underscores the impact of the microenvironment on SC behaviour. Similarly, a colony derived from a single cultured HFSC can produce epidermis, sebaceous glands and hair follicles when engrafted onto a host recipient mouse, even though in normal homeostasis, HFSCs contribute only to hair regeneration52 (FIG. 2C). Such plasticity is a common feature of transplantation studies, which have been widely employed in evaluating the ability of SCs to undergo long-term self-renewal and multilineage reconstitution. As such, when taken from their niche and exposed to what is likely to be a stressful situation, as in a graft or transplantation, SCs often adopt their full spectrum of lineage potential as opposed to the restricted steady-state output. Such behaviour is similar to that of wound-induced SCs12,16–18,36,37,150.

Plasticity in wound repair.

Wound repair represents another classic scenario of SC plasticity in response to stress (FIG. 2C). For instance, as discussed above, steady-state HSCs contribute minimally to downstream lineages; however, upon stimulation or injury, quiescent HSCs become activated and contribute to all the blood lineages to restore homeostasis11,12,151–153 — a plastic process highly distinguished from their homeostatic behaviours.

Compared with the plasticity in the haematopoietic system, ectopic lineages may come into play during plasticity in epithelial organs. Faced with the need to survive in a harsh environment involving broken blood vessels, damaged tissue and a new immune cell milieu, SCs must adapt. Upon skin injury, epithelial SCs exhibit lineage infidelity, where HFSCs adopt features characteristic of EpdSCs while still retaining some of their own features112. Lineage infidelity is transient during wounding and resolves by the end of wound repair, such that HFSCs switch to an epidermal fate upon regenerating the epidermis and finding themselves in the EpdSC niche112. Of note, upon injury, EpdSCs also transiently co-express both epidermis and hair follicle lineage markers112, as do SCs in the upper pilosebaceous unit above the bulge112,154, suggesting that lineage infidelity occurs regardless of SC origin, rather than reflecting their perturbed microenvironment. Analogously, in the injured pancreas, acinar cells become proliferative and duct-like and begin to exhibit markers from both lineages. This so-called acinar-to-ductal metaplasia is crucial for pancreas regeneration (reviewed in REFS 155,156) and is reminiscent of the requirement of lineage infidelity in skin wounding112.

What causes lineage infidelity, and how does it promote wound repair? HFSCs have long been recognized to contribute to epidermal re-epithelialization, and conversely, EpdSCs can contribute to hair follicle regeneration, although the degree and duration of the contributions seem to vary according to the type of injury154,157–159. Mechanistically, it is now becoming evident that wound-induced transcription factors drive the onset of lineage infidelity by re-modelling stress-specific regulatory elements (epicentres), leading to suppression of certain SC identity genes and to activation of other genes112. Among the wound-induced transcription factors, ETS2 is particularly intriguing as it is phosphorylated and activated by RAS–MAPK signalling, which is required for wound repair, and its forced activation is sufficient to set off lineage infidelity without injury112. ETS2 is also robustly activated during the malignant progression of skin SCs160 (discussed below). Notably, these stress epicentres, when tested in vivo, specifically activated reporter expression upon wounding and/or during malignant progression but were silent under homeostasis112.

Taken together, these results suggest that inhibitory signals from the native niche provide a molecular brake to plasticity. When the brake is unhinged, SCs have no blueprint to follow, and their plasticity is unleashed. However, regardless of the extent to which the niche has been altered, SCs do eventually remember what they are and where they come from, and this memory poses an ultimate barrier to plasticity.

Intrinsic memory against plasticity.

It has been observed that cell-autonomous, epigenetic mechanisms underlie the ability of SCs to remember an inflammatory assault long after the initial stimuli have been withdrawn18,114. For example, when skin is exposed to an inflammatory agent that provokes immune cell secretion of interleukins 17 and 22, the EpdSCs respond by phosphorylating and activating signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3). The outcome is extensive chromatin remodelling, making new regulatory elements that harbour sequence motifs accessible not only for STAT3 but also for master transcription factors of EpdSCs114. Remarkably, some of these regulatory elements remain accessible in EpdSCs long after the inflammation has resolved, and epidermal pathology has returned to normal. Of note, this epigenetic memory can occur in the absence of B and T lymphocytes and also of several innate immune cell types that have previously been shown to possess memory of inflammatory stress114. This ability of EpdSCs to remember stress and maintain chromatin in a poised state, in addition to their vantage point of being long-lived surveyors of tissue damage44, seems to equip these cells with an arsenal of abilities to rapidly respond to future encounters of stress.

Using a multifluorescent labelling method of clonal tracking and isolation, a recent study revealed that the lineage bias of each HSC is maintained after it has left its native niche and settled into a foreign environment upon engraftment18. This tantalizing finding is consistent with the notion that HSCs may possess intrinsic memory of where they came from. Importantly, by matching the molecular phenotypes with the functional outputs of each individual clones, the authors were able to trace the molecular mechanism of such a memory to the level of epigenetic regulation18. Similarly, in aged SCs of various tissues, at least part of the ageing phenotype seems to also be cell autonomous because it is transferable when SCs are transplanted into young recipients and is intrinsically maintained161–163. Interestingly, when aged HFSCs are cultured, they are less efficient in forming colonies during in vitro adaption164. Among those that do form colonies, however, aged HFSCs are able to undergo several passages at a level comparable to that of their youthful counterparts. That said, they eventually become exhausted — in contrast to young HFSCs, which exhibit long-term self-renewal — implying that intrinsic differences of ageing are memorized even when both aged and young SCs are facing the same microenvironment (culture)164.

Taken together, plasticity might be understood in multiple folds. First, upon local disturbance and loss of SCs, other SCs and/or their progenies home in to fill the niche vacancy. Second, upon heightened stress, such as wounding and transplantation, SCs exit the niche to orchestrate repair and restore homeostasis. How resilient SC identity is in the face of environmental changes and what it takes to stimulate plasticity and alter fate will likely differ for different SC types, based upon their composite of extrinsic drivers and intrinsic stability.

Cellular plasticity in cancer

Perhaps the most extreme form of plasticity is seen in malignant progression, where the tumour-initiating, so-called cancer SCs (CSCs) undergo long-term self-renewal and are able to reconstitute the entire tumour165–168. Curiously, many oncogenic driver mutations (BOX 4) occur in master developmental pathways or chromatin factors that are crucial for cellular reprogramming169, suggesting that cell plasticity is an important driver programme that is hijacked by cancer.

Box 4 |. Drivers of plasticity in cancer.

By definition, driver mutations confer a growth advantage to cancers260–262 and are positively selected for. Lack of evidence for positive selection disqualifies mutations from being functionally relevant in a given tumour, although these passenger mutations can act as a clock, recording the evolutionary trajectory of a tumour, and may contribute to its heterogeneity. Observations of clonal selection during cancer progression have led to a multistep cancer progression model263 consistent with the clonal sweep phenomenon typically seen in late-stage cancers across many human malignancies125,126,264–267.

Recent evidence suggests that clonal selection is not unique to cancer. Normal, non-phenotypic skin in the sun-exposed eyelid is riddled with pre-malignant mutations, including known cancer drivers of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas, indicative of positive clonal selection even under normal physiological conditions268. This phenomenon is reminiscent of the concept of field cancerization, initially described in head and neck cancer, in which local secondary tumours frequently occur at the site of primary tumour removal (sporadic nonfamilial cases), suggesting a cancerous ‘field’ of premalignant mutations in tumour-adjacent epidermis269. A notable example are early somatic mutations in TP53, which are known to occur in a patched fashion in otherwise normal epithelial mucosa270–275. Analogously, differentiation imbalance in single oesophageal progenitor cells leads to field change276. Besides epithelial cancers, similar examples, so called pre-leukaemic clones, can also be found in haematological malignancies265,277,278.

There are multiple important implications of these observations in the context of cancer plasticity. First, although all driver mutations confer growth advantages to their host cells, sequences in which driver mutations occur may profoundly affect cancer phenotypes. Second, compared with a cancerous lesion, its adjacent tissue may no longer be considered normal despite not displaying a tumour phenotype. Finally, in addition to their conventional roles in cell proliferation and survival, tumour suppressors have been implicated as a barrier to unscheduled lineage plasticity regardless of tissue types. In the case of p53, such a role in promoting cancer plasticity may be indirectly attributed to its function in regulating cell proliferation or may be more directly rooted in its control of cell fate gene expression by cooperating with lineage transcription factors279.

Cancer hijacks plasticity to fuel malignancy.

Malignant SCs can be viewed as SCs that perceive their surrounding tissue as constitutively damaged and hence fail to cease their regenerative behaviours. Certain concepts of normal SC plasticity can be readily applied in the understanding of CSC plasticity, for example, the idea of intrinsic memory. Whereas transplantation experiments have revealed which cell populations are capable of giving rise to leukaemia170–172, definitive documentation has come from in vivo lineage tracing, where SCs and in a few cases progenitors have been pinpointed as the source of their CSC counterparts133,173–176. Even though multiple cell types of a given tissue may give rise to a certain cancer, the exact cell of origin can have an impact on the outcome of cancer phenotypes in regard to their malignant progression and metastasis potential177,178. This finding is reminiscent of the intrinsic memory discussed above in the context of normal SC plasticity, whereby SCs maintain memories of their original source after their niche has changed — in the case of cancer progression, CSC function can be affected by the identity and molecular property of their normal SC origin.

That said, the overall molecular signatures of CSCs diverge from their normal SC counterparts160,177,179, a facet likely attributable to a combination of genetic alternations and niche aberrations, with the latter replete with new blood vessels, immune cells, fibroblasts and nerves, among others. Indeed, such temporal and spatial heterogeneity in the tumour microenvironment correlates with CSC heterogeneity, leading to therapeutic resistance and disease relapse180,181.

It has long been recognized that cancers can simultaneously express intermediate filament genes from mixed lineages, an oft-used diagnostic tool for pathologists182. Intriguingly, CSCs of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) constitutively co-express EpdSC and HFSC lineage factors, analogous to what occurs transiently when their normal SCs engage in wound response112 (FIG. 3Aa). Lineage infidelity has also been observed for leukaemia (FIG. 3Ab), retinoblastoma (FIG. 3Ac) and lung tumours183–185. In human acute myeloid leukaemia, co-expression of lymphoid and myeloid lineage markers is associated with dismal prognosis186. Moreover, accompanying functional studies on both skin SCC and retinoblastoma suggest that tumours are critically dependent upon lineage infidelity to propagate112,183. Of note, this lineage infidelity seems to be intrinsically maintained, as it can be detected even in SCCs that have metastasized from the skin to the lung112. The extent to which these states are driven by genetic mutations versus the tumour microenvironment is still under investigation.

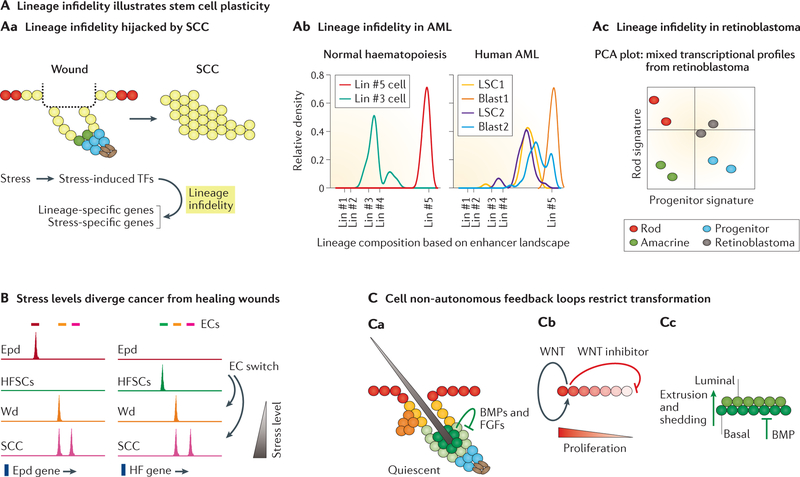

Figure 3 |. Stem cell plasticity in cancer.

A | Stem cell (SC) lineage infidelity is a unique manifestation of plasticity. Aa | Transient in wound repair and sustained in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), lineage infidelity is driven by stress-induced transcription factors, which activate stress-specific and lineage-specific gene expression. Ab | Based upon enhancer landscaping at the whole-genome level, normal haematopoiesis has a defined lineage (Lin) profile (Lin #3 or #5 cell), whereas human acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) exhibits mixed lineage profiles in either leukaemia stem cells (LSCs) or leukaemic blasts at the single-cell level. Ac | Principle component analysis (PCA) based on transcriptional profiles also reveals mixed lineage profiles in retinoblastoma. B | Stress levels are likely to be a key parameter that diverges cancer from wound repair. Upon wounding (Wd), hair follicle SCs (HFSCs) sense stress and activate epidermis (Epd) genes as HFSC homeostatic regulatory epicentres (ECs) collapse and stress ECs emerge to transiently dominate chromatin regulation. As stress levels elevate in tumorigenesis, new tumour ECs driven by high levels of stress-induced transcription factors work together with wound-induced ECs to make lineage infidelity a permanent state. C | Feedback controls the return of SCs to dormancy to restrict unscheduled plasticity in normal homeostasis. Ca | Progeny of HFSCs home back to their niche to confer inhibitory signals, such as bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), that keep HFSCs in quiescence. Cb | Epidermal SCs generate a short-range stimulatory WNT signal for self-renewal and a longer-range WNT inhibitor that limits the zone of proliferative activity. Cc | In airway epithelia wound repair, basal cells sense their local density and respond by extrusion and shedding to limit the proliferative response, in addition to inhibition by mesenchymal BMP signals. TFs, transcription factors. Part Ab is adapted from REF. 184, Macmillan Publishers Limited. Part Ac is adapted with permission from REF. 183, Elsevier. Part B is adapted with permission from REF. 112, Elsevier.

Plasticity may also underlie therapeutic resistance in cancer. In colorectal cancers, LGR5-negative cells actively convert to LGR5-positive cells to drive chemoresistance and relapse187. In prostate cancer under drug treatment, luminal cells undergo phenotypic conversion to basal neuroendocrine lineages upon ectopic activation of certain key transcription factors188–190. These examples of plasticity likely reflect fate-escaping mechanisms rooted in tissue-specific development and regeneration programmes.

Cancer — a wound that never heals.

Initially proposed by Rudolf Virchow in the mid-19th century, the interwoven parallels between wounds and cancer have attracted many basic and clinical researches. With regard to SC plasticity, why does it persist in cancer and yet resolve in wounds?

The level of stress may be one crucial factor to distinguish malignancy from wound repair (FIG. 3B). As discussed earlier, ectopic activation of stress-responsive transcription factors leads to the rapid collapse of homeostatic enhancers and a switch to stress-specific ones, hence diminishing the dependence upon key SC identity genes and marking the onset of lineage infidelity. As oncogenic stress progressively increases, new cancer-specific epicentres join the force to sustain plasticity112.

By contrast, wounds heal by re-establishing normal tissue hierarchy. While further investigation will be necessary to answer this question, it is interesting to speculate that the differentiated cells of a healing wound may serve as non-cell-autonomous brakes to bring their SC parents back to quiescence (FIG. 3C). Indeed, there is now mounting evidence that differentiating progenies transmit inhibitory signals to their SC parents to restrict their self-renewal. Progeny of HFSCs home back to their niche to confer inhibitory signs that restrict the intervals between hair cycles, thereby preserving the SC pool56. Adding a twist to autocrine signalling, EpdSCs generate a short-range stimulatory WNT signal for self-renewal, soon thereafter producing a longer range WNT inhibitor that limits the zone of proliferative activity191. Similarly, in airway epithelia, wounds stimulate the production of a BMP inhibitor to promote basal SC proliferation and re-epithelialization. Meanwhile, cell crowding leads to extrusion and shedding of apoptotic cells from the basal layer and limits the proliferative response192. Of note, these homeostatic brakes extend beyond epithelial tissues and apply to many SCs. As discussed earlier, loss of macrophages39,40 or megakaryocytes42,43 induces HSC activation, suggesting that their presence restrains HSCs from activation. These examples are all consistent with the notion that the roadblock to SC plasticity in normal tissues relies upon instructive cues not only from their niches but also from their progeny. As these checks and balances disintegrate, SCs become unhinged, entering futile cycles of reiterative regeneration and persistent plasticity en route to malignancy. Defining the nature of these negative feedback loops, in which SCs transmit and receive signals in normal homeostasis and wound repair, is likely to generate novel therapeutic candidates for both regenerative medicine and cancer treatments.

Conclusions and perspectives

From the dawn of their identification, tissue SCs have captured the interest of basic researchers fascinated by their self-renewing and multilineage differentiation capacities, as well as physicians interested in harnessing these powers for regenerative medicine and cancer therapeutics. Waves of technological revolutions over the past four decades have greatly advanced our understanding, although many pieces to the SC puzzle remain. We still lack a complete picture of any tissue SC niche, let alone the myriad of complex molecular communications that take place within the niche to coordinate SC activity during homeostasis and wound repair. How spatial and temporal niche information impinge on the functional heterogeneity of SCs is only just emerging. And just as we’ve begun to dissect the complex crosstalk between SCs and their neighbours, we have learned that interactions with niche factors, for example, the immune system, vasculature and nerves, are critical for SC behaviour, as are feedback signals from SC progenies. These findings add further molecular wires to the SC communication switchboard. Our knowledge of how damaged tissue disrupts this circuitry is still in its infancy, and we have only surmised the likely factors involved by characterizing the changes in behaviour and plasticity when SCs are confronted with a wounded state. The roles of translational regulation, non-coding RNAs and metabolism in contributing to these dynamics remain largely unexplored, as are the steps along the route to sustained plasticity in tumour progression and metastases. In the future, the better we understand SC plasticity, the more we will be empowered with the full potential of SCs for regenerative medicine. This knowledge should also enable us to understand how cancer hijacks normal SC plasticity, which could be harnessed in devising innovative cancer therapies to overcome resistance and disease relapse. If we think of SCs as the Sun of this molecular solar system, there is no doubt that many exciting breakthroughs will emerge as new planets and stars are discovered.

Totipotenc.

The ability of a zygote to give rise to all the lineages of the embryo and extra-embryonic tissues. It differs from the ability of embryonic stem cells to generate all lineages of the embryo (pluripotency) and the ability of adult stem cells to reconstitute multiple (multipotency), a few selective (oligopotency) or a single lineage (unipotency) of a tissue.

Plasticity.

In this Review, any process that is distinct from homeostasis. For example, the increased differentiation of haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) into cells of all blood lineages upon injury is in sharp contrast to their homeostatic behaviour, where HSCs contribute minimally; therefore, we consider such behaviour to be plastic. Plasticity is not restricted to stem cells, although this Review focuses primarily on stem cell plasticity.

Stemness.

The unique ability of stem cells to undergo long-term self-renewal and multilineage differentiation.

Engraftment.

A procedure in which transplantation of a stem cell of interest is grafted into a host recipient animal to test for the ability of the cell to contribute to host tissue regeneration.

Epicentres.

DNA regulatory elements of about 1 kb in length that sit within broad chromatin domains marked by histone 3 lysine 27 acetylation, so‑called super-enhancers or stretch-enhancers and are bound by clustered cell identity and/or stress-specific transcription factors.

Lineage infidelity.

A term initially used in blood malignancies to describe the presence of multiple differentiation markers specific to distinct lineages in the same cell. In epithelial wounding, lineage infidelity was observed for skin stem cells, which were found to co-express markers of otherwise confined lineages and functionally rely upon them to cope with stress and mediate repair. Lineage infidelity occurs transiently during wound repair but is hijacked by squamous cell carcinoma where it becomes sustained and is essential for malignancy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank R. C. Adam, M. Laurin and S. Ellis for discussions and critical feedback of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AR05042). Y.G. is an awardee of Robertson Therapeutic Development Fund. E.F. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Reviewer information

Nature Reviews Genetics thanks Daisuke Nakada and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

References

- 1.Schofield R The relationship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood Cells 4, 7–25 (1978).In this paper, the SC niche concept is coined and formally elaborated upon.

- 2.Till JE & McCulloch EA A direct measurement of the radiation sensitivity of normal mouse bone marrow cells. Radiat. Res 14, 213–222 (1961).This article presents the discovery of spleen colony-forming units, clonogenic bone marrow precursors that give rise to macroscopic spleen colonies after transplantation into irradiated recipient mice, a work directly leading to the definition of a SC.

- 3.Dick JE, Magli MC, Huszar D, Phillips RA & Bernstein A Introduction of a selectable gene into primitive stem cells capable of long-term reconstitution of the hemopoietic system of W/Wv mice. Cell 42, 71–79 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemischka IR, Raulet DH & Mulligan RC Developmental potential and dynamic behavior of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell 45, 917–927 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muller-Sieburg CE, Whitlock CA & Weissman IL Isolation of two early B lymphocyte progenitors from mouse marrow: a committed pre-pre-B cell and a clonogenic Thy-1-lo hematopoietic stem cell. Cell 44, 653–662 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spangrude GJ, Heimfeld S & Weissman IL Purification and characterization of mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Science 241, 58–62 (1988).This is the first prospective isolation of HSCs using FACS, which showed that HSCs self-renew and give rise to all blood lineages.

- 7.Morrison SJ & Weissman IL The long-term repopulating subset of hematopoietic stem cells is deterministic and isolatable by phenotype. Immunity 1, 661–673 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forsberg EC, Serwold T, Kogan S, Weissman IL & Passegue E New evidence supporting megakaryocyte-erythrocyte potential of flk2/flt3+ multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. Cell 126, 415–426 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kondo M, Weissman IL & Akashi K Identification of clonogenic common lymphoid progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Cell 91, 661–672 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akashi K, Traver D, Miyamoto T & Weissman IL A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature 404, 193–197 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson A et al. Hematopoietic stem cells reversibly switch from dormancy to self-renewal during homeostasis and repair. Cell 135, 1118–1129 (2008).This is the initial demonstration via label retention analysis that HSCs are dormant under steady state and cycle only five times per a mouse’s lifetime but contribute significantly to downstream lineage output upon injury.

- 12.Foudi A et al. Analysis of histone 2B-GFP retention reveals slowly cycling hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol 27, 84–90 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernitz JM, Kim HS, MacArthur B, Sieburg H & Moore K Hematopoietic stem cells count and remember self-renewal divisions. Cell 167, 1296–1309 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheshier SH, Morrison SJ, Liao X & Weissman IL In vivo proliferation and cell cycle kinetics of long-term self-renewing hematopoietic stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 3120–3125 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Passegue E, Wagers AJ, Giuriato S, Anderson WC & Weissman IL Global analysis of proliferation and cell cycle gene expression in the regulation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell fates. J. Exp. Med 202, 1599–1611 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun J et al. Clonal dynamics of native haematopoiesis. Nature 514, 322–327 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Busch K et al. Fundamental properties of unperturbed haematopoiesis from stem cells in vivo. Nature 518, 542–546 (2015).References 16 and 17 used in vivo lineage tracing via endogenous tagging to demonstrate that multipotent progenitors rather than HSCs fuel the steady-state homeostasis.

- 18.Yu VW et al. Epigenetic memory underlies cell-autonomous heterogeneous behavior of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell 167, 1310–1322 (2016).By tracing and isolating multifluorescent clones, this study matches molecular profiles with functional output of HSCs and reveals that epigenetic mechanisms underlie HSC intrinsic memory and functional heterogeneity.

- 19.Gong JK Endosteal marrow: a rich source of hematopoietic stem cells. Science 199, 1443–1445 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie Y et al. Detection of functional haematopoietic stem cell niche using real-time imaging. Nature 457, 97–101 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lo Celso C et al. Live-animal tracking of individual haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in their niche. Nature 457, 92–96 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiel MJ et al. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell 121, 1109–1121 (2005).This study discusses simple combinations of lineage markers in FACS distinguished between HSCs and progenitor cells and reveals for the first time the association of HSCs with sinusoidal endothelium in spleen and bone marrow.

- 23.Kunisaki Y et al. Arteriolar niches maintain haematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Nature 502, 637–643 (2013).This paper describes the illustration of arteriolar endothelium as a HSC niche.

- 24.Ding L, Saunders TL, Enikolopov G & Morrison SJ Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 481, 457–462 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding L & Morrison SJ Haematopoietic stem cells and early lymphoid progenitors occupy distinct bone marrow niches. Nature 495, 231–235 (2013).References 24 and 25 provide direct evidence via cell type-specific gene ablation that endothelial and perivascular cells act as obligatory HSC niches by providing HSC maintenance factors stem cell factor/ KIT ligand (KITL) (reference 24) and CXCL12 (reference 25), whereas early lymphoid progenitors are dependent on endosteal CXCL12 (reference 25).

- 26.Kobayashi H et al. Angiocrine factors from Akt-activated endothelial cells balance self-renewal and differentiation of haematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol 12, 1046–1056 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamplin OJ et al. Hematopoietic stem cell arrival triggers dynamic remodeling of the perivascular niche. Cell 160, 241–252 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Acar M et al. Deep imaging of bone marrow shows non-dividing stem cells are mainly perisinusoidal. Nature 526, 126–130 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou BO, Yue R, Murphy MM, Peyer JG & Morrison SJ Leptin-receptor-expressing mesenchymal stromal cells represent the main source of bone formed by adult bone marrow. Cell Stem Cell 15, 154–168 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Omatsu Y et al. The essential functions of adipo-osteogenic progenitors as the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell niche. Immunity 33, 387–399 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Noda M & Nagasawa T Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity 25, 977–988 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yue R, Zhou BO, Shimada IS, Zhao Z & Morrison SJ Leptin receptor promotes adipogenesis and reduces osteogenesis by regulating mesenchymal stromal cells in adult bone marrow. Cell Stem Cell 18, 782–796 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou BO et al. Bone marrow adipocytes promote the regeneration of stem cells and haematopoiesis by secreting SCF. Nat. Cell Biol 19, 891–903 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mendez-Ferrer S et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature 466, 829–834 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asada N et al. Differential cytokine contributions of perivascular haematopoietic stem cell niches. Nat. Cell Biol 19, 214–223 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pei W et al. Polylox barcoding reveals haematopoietic stem cell fates realized in vivo. Nature 548, 456–460 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henninger J et al. Clonal fate mapping quantifies the number of haematopoietic stem cells that arise during development. Nat. Cell Biol 19, 17–27 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujisaki J et al. In vivo imaging of Treg cells providing immune privilege to the haematopoietic stem-cell niche. Nature 474, 216–219 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winkler IG et al. Bone marrow macrophages maintain hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niches and their depletion mobilizes HSCs. Blood 116, 4815–4828 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chow A et al. Bone marrow CD169+ macrophages promote the retention of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the mesenchymal stem cell niche. J. Exp. Med 208, 261–271 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ludin A et al. Monocytes-macrophages that express alpha-smooth muscle actin preserve primitive hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow. Nat. Immunol 13, 1072–1082 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruns I et al. Megakaryocytes regulate hematopoietic stem cell quiescence through CXCL4 secretion. Nat. Med 20, 1315–1320 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao M et al. Megakaryocytes maintain homeostatic quiescence and promote post-injury regeneration of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Med 20, 1321–1326 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gonzales KAU & Fuchs E Skin and its regenerative powers: an alliance between stem cells and their niche. Dev. Cell 43, 387–401 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brownell I, Guevara E, Bai CB, Loomis CA & Joyner AL Nerve-derived sonic hedgehog defines a niche for hair follicle stem cells capable of becoming epidermal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 8, 552–565 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horsley V et al. Blimp1 defines a progenitor population that governs cellular input to the sebaceous gland. Cell 126, 597–609 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jensen KB et al. Lrig1 expression defines a distinct multipotent stem cell population in mammalian epidermis. Cell Stem Cell 4, 427–439 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nijhof JG et al. The cell-surface marker MTS24 identifies a novel population of follicular keratinocytes with characteristics of progenitor cells. Development 133, 3027–3037 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Snippert HJ et al. Lgr6 marks stem cells in the hair follicle that generate all cell lineages of the skin. Science 327, 1385–1389 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watt FM Engineered microenvironments to direct epidermal stem cell behavior at single-cell resolution. Dev. Cell 38, 601–609 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wabik A & Jones PH Switching roles: the functional plasticity of adult tissue stem cells. EMBO J 34, 1164–1179 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Geoghegan A, Polak L & Fuchs E Self-renewal, multipotency, and the existence of two cell populations within an epithelial stem cell niche. Cell 118, 635–648 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Claudinot S, Nicolas M, Oshima H, Rochat A & Barrandon Y Long-term renewal of hair follicles from clonogenic multipotent stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 14677–14682 (2005).References 52 and 53 are the first to show that cells from the bulge are HFSCs that undergo long-term self-renewal and reconstitute all lineages of the pilosebaceous unit and the epidermis upon engraftment.

- 54.Ito M et al. Stem cells in the hair follicle bulge contribute to wound repair but not to homeostasis of the epidermis. Nat. Med 11, 1351–1354 (2005).This study shows that HFSCs of the bulge do not contribute to the interfollicular epidermis under steady state and do so only when subjected to epidermal wounding.

- 55.Levy V, Lindon C, Harfe BD & Morgan BA Distinct stem cell populations regenerate the follicle and interfollicular epidermis. Dev. Cell 9, 855–861 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hsu YC, Pasolli HA & Fuchs E Dynamics between stem cells, niche, and progeny in the hair follicle. Cell 144, 92–105 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greco V et al. A two-step mechanism for stem cell activation during hair regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 4, 155–169 (2009).This study shows that by having a polarized niche stimulus, stem cells become differentially activated, enabling the niche to conserve its residents.

- 58.Yang H, Adam RC, Ge Y, Hua ZL & Fuchs E Epithelial-mesenchymal micro-niches govern stem cell lineage choices. Cell 169, 483–496 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hsu YC, Li L & Fuchs E Transit-amplifying cells orchestrate stem cell activity and tissue regeneration. Cell 157, 935–949 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tanimura S et al. Hair follicle stem cells provide a functional niche for melanocyte stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 8, 177–187 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morgner J et al. Integrin-linked kinase regulates the niche of quiescent epidermal stem cells. Nat. Commun 6, 8198 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Plikus MV et al. Cyclic dermal BMP signalling regulates stem cell activation during hair regeneration. Nature 451, 340–344 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Woo WM, Zhen HH & Oro AE Shh maintains dermal papilla identity and hair morphogenesis via a Noggin-Shh regulatory loop. Genes Dev 26, 1235–1246 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rompolas P, Mesa KR & Greco V Spatial organization within a niche as a determinant of stem-cell fate. Nature 502, 513–518 (2013).This study shows that upon loss of hair follicle bulge SCs via laser ablation, hair germ and upper hair follicle cells in the vicinity can repopulate the emptied niche.

- 65.Chi W, Wu E & Morgan BA Dermal papilla cell number specifies hair size, shape and cycling and its reduction causes follicular decline. Development 140, 1676–1683 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Clavel C et al. Sox2 in the dermal papilla niche controls hair growth by fine-tuning bmp signaling in differentiating hair shaft progenitors. Dev. Cell 23, 981–994 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Festa E et al. Adipocyte lineage cells contribute to the skin stem cell niche to drive hair cycling. Cell 146, 761–771 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Plikus MV et al. Self-organizing and stochastic behaviors during the regeneration of hair stem cells. Science 332, 586–589 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]