Abstract

Islet-reactive memory CD4+ T cells are an essential feature of type 1 diabetes (T1D) as they are involved in both spontaneous disease and in its recurrence after islet transplantation. Expansion and enrichment of memory T cells have also been shown in the peripheral blood of diabetic patients. Here, using high-throughput sequencing, we investigated the clonal diversity of the TCRβ repertoire of memory CD4+ T cells in the pancreatic lymph nodes (PaLN) of non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice and examined their clonal overlap with islet-infiltrating memory CD4 T cells. Both prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice exhibited a restricted TCRβ repertoire dominated by clones expressing TRBV13-2, TRBV13-1 or TRBV5 gene segments. There is a limited degree of TCRβ overlap between the memory CD4 repertoire of PaLN and pancreas as well as between the prediabetic and diabetic group. However, public TCRβ clonotypes were identified across several individual animals, some of them with sequences similar to the TCRs from the islet-reactive T cells suggesting their antigen-driven expansion. Moreover, the majority of the public clonotypes expressed TRBV13-2 (Vβ8.2) gene segment. Nasal vaccination with an immunodominat peptide derived from the TCR Vβ8.2 chain led to protection from diabetes, suggesting a critical role for Vβ8.2+ CD4+ memory T cells in T1D. These results suggest that memory CD4+ T cells bearing limited dominant TRBV genes contribute to the autoimmune diabetes and can be potentially targeted for intervention in diabetes. Furthermore, our results have important implications for the identification of public T cell clonotypes as potential novel targets for immune manipulation in human T1D.

Keywords: autoimmune diabetes, TCR, NOD, memory CD4, public clonotypes, CDR3 sequences

1. Introduction

Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) is a clinical consequence of the autoimmune T cell-mediated destruction of the insulin-producing β cells within the islets of Langerhans (Yoshida and Kikutani, 2000). NOD mice spontaneously develop T1D and share multiple genetic susceptibility loci and pathological characteristics with the human disease. Thus, NOD mice are frequently used as an animal model for T1D studies addressing the genetic basis, cellular mechanisms of autoimmunity, and regulation of disease (Serreze and Leiter, 1994). Previous studies have demonstrated that both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells play a critical role in the initiation and progression of diabetes (Santamaria, 2001).

The diversity within the TCR repertoire is ensured through somatic recombination of germline-encoded variable (V), diversity (D), and junctional (J) gene segments. Nucleotide deletions at the coding ends and nucleotide additions at the V(D)J junctions also contribute substantially to TCR repertoire diversity (Nikolich-Zugich et al., 2004). The TCR diversity is a function of the third hypervariable complementary-determining (CDR3) region, which lies at the intersection between the Vβ, Dβ, and Jβ and Vα and Jα gene segments within the TCRβ and TCRα chains, respectively. The CDR3 region encodes that part of the TCR which predominantly interacts with antigenic peptide/MHC complexes. Thus, even when T cell clones express the same Vβ/Jβ genes rearrangement, they can be identified by the unique combination of their CDR3 sequences (TCR clonotypes) (Arstila et al., 1999). Accordingly, the complexity and distribution of TCRs within specific T cell populations will reflect the degree of complexity of the T-cell response.

Previous studies have shown that islet Ag-specific T cells isolated from the periphery as well as from islets from both prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice recognize different islet-Ags and use different TCRs (Delovitch and Singh, 1997). Analysis of the TCR repertoires of pancreatic T cells has suggested a restricted TCR Vβ and Jβ gene usage and/or limited CDR3 diversity among islet-infiltrating T cells from human diabetic patients and prediabetic NOD mice (Drexler et al., 1993, Sarukhan et al., 1994, Santamaria et al, 1994, Galley and Danska, 1995, Yang et al., 1996, Baker et al., 2002). Restricted TCR repertoires have also been shown among T cells responding to immunodominant peptides of autoantigens (Simone et al., 1997, Tikochinski et al., 1999, Quinn et al., 2001, Wong et al., 2006). Li et al. (2009) have shown that specific TCR Vβ chains are predominantly used by single islet-infiltrating CD4+ T cells that react to a mimetic peptide for the diabetogenic clone BDC2.5. Previously we showed by CDR3 spectratyping analysis that a limited number of TCR Vβ families are significantly perturbed in pancreatic lymph nodes (PaLN) of NOD mice in both spontaneous and acute T1D models, suggesting that expanded T cells within these Vβ families are naturally and efficiently selected in the periphery to contribute to an aggressive autoimmune response (Marrero et al., 2012). A diverse TCR Vβ expression has also been found in T cells infiltrating islets of diabetic NOD mice and among islet-reactive T cell clones (Nakano et al., 1991, Candéias et al., 1991, Waters et al., 1992, Santamaria et al., 1995). This diversity in TCR expression might reflect intra- and inter-molecular epitope spreading during the disease progression (Zechel et al., 1998).

A number of reports have shown that islet-specific memory CD4+ T cells found in the peripheral repertoire of T1D patients, including newly diagnosed, with clinical disease, and those with recurrent autoimmunity after β-cell replacement, express a skewed TCR Vβ repertoire and, in some cases, identical CD3 sequences (Monti et al., 2007, Laughlin et al., 2008, Axelsson et al., 2011, Öling et al., 2012). Similarly in NOD mice it has been shown that islet-infiltrating CD4+ T cells used preferentially specific TCR Vβ chains (Li et al., 2009, Diz et al., 2012). Our previous work highlighted that the TCRβ repertoire of islet-infiltrating memory CD4+ T cells is highly comparable between prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice, exhibiting a significantly high degree of TCRβ diversity and dominance of TCR β-chain variable (TRBV)13-3 (Vβ8.1), TRBV1 (Vβ2), and TRBV19 (Vβ6) gene segments in both prediabetic and diabetic mice (Marrero et al., 2013). In this study we carried out a high-throughput sequencing analysis of the TCRβ repertoire of PaLN-memory CD4+ T cells to investigate the degree of overlap between the memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire in PaLNs and islets and within PaLNs of prediabetic and diabetic mice.

Here we show that the TCRβ repertoire of memory CD4+ T cells is highly restricted to specific TRBV gene segments. Memory CD4+ T cells expressing TRBV13-2 (Vβ8.2), TRBV13-1 (Vβ8.3), and TRBV5 (Vβ1) are dominant within the PaLN-memory CD4+ repertoire of both prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice. Some of the public TCRβ clonotypes with sequences similar to islet Ag-reactive TCRs are present in pancreas in both prediabetic and diabetic mice. Most of the public TCRβ clonotypes use preferentially the TRBV13-2 (Vβ8.2) gene segment. Using TCR-based vaccination approach we show that Vβ8.2+ T cells play a critical role in T1D in NOD mice. Our study also reveals that islet-reactive TCRs are present at very low frequency in the PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire. The dominant use of a few TRBV gene segments (Vβ chains) within the memory CD4+ repertoire in prediabetic or diabetic mice as well as a major influence on disease progression following targeting of a dominant clonotype have important implications for the study of public memory T cell clonotypes in human T1D.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Mice

Female NOD (NOD/ShiLtJ-H2g7) and NOR mice (NOR/LtJ-H2g7) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and Taconic Biosciences (Germantown, NY). Mice were bred and housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in our animal facility at the Torrey Pines Institute for Molecular Studies (San Diego, CA). Mice were used between 2 and 32 weeks of age. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines for animal care.

2.2. TCR Peptides

Vβ8.2 TCR-peptides used were the same as reported earlier (Kumar and Sercarz, 1993). The amino acid sequences of these TCR-peptides are:

B1 (1–30) EAAVTQSPRNKVAVTGGKVTLSCNQTNNHNL

B2 (21–50) LSCNQTNNHNNMYWYRQDTGHGLRLIHYSY

B3 (41–70) HGLRLIHYSYGAGSTEKGDIPDGYKASRPS

B4 (61–90) PGDYKASRPSQENFSLILELATPSQTSVYF

B5 (76–101) LILELATPSQTSVYFCASGDAGGGYE

Vβ17 TCR-peptide (80–94) SSEEDDSALYLCAS

2.3. Diabetes onset

Mice were monitored for diabetes twice a week by measuring blood glucose levels (BGL) using Accu-Check Compact Plus (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Mice with BGL >250 mg/dl were tested the next day and were considered diabetic if the second reading was also >250 mg/dl. For the mice included in the diabetic group, diabetes onset occurred between 12 and 26 weeks of age. In this group, PaLN were isolated the same day that the mice were considered diabetic.

2.4. Cell preparation

Single cell suspensions of PaLN or draining popliteal and inguinal lymph nodes from individual mice were prepared in PBS using a 70-µm polystyrene mesh cell strainer (BD Biosciences). After two washes in PBS, cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion. For sorting of CD4+CD44high T cells, lymphocytes from PaLN of individual mice were resuspended in sorting buffer (0.1% BSA in PBS), treated with Fc block (rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32) (BD Biosciences) and then stained with anti-CD4-APC and anti-CD44-PE mAbs (BD Biosciences) on ice for 30 min. Cells were washed twice and resuspended at 5 × 106/ml in 500 µl of sorting buffer. CD4+CD44high T cells were sorted on a FACSVantage flow cytometer with Diva software (BD Biosciences) at The Scripps Research Institute Flow Cytometry Core Facility (La Jolla, CA). Sorted cells were washed once in PBS and the cell pellet was frozen on dry ice for RNA extraction. For sorting of CD4+CD44high T cells, total lymphocytes were gated on forward and side scatter and doublets and dead cells were excluded. A histogram showing the expression of CD44 on gated CD4+ T cells was used to identify memory CD4+CD44high T cells, which were defined as CD4+ T cells expressing the highest level of CD44.

2.5. RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from single cell suspensions of either sorted CD4+CD44high T cells or PaLNs of individual mice using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The entire sample was subjected to cDNA synthesis using the SuperScript™ First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Life Technologies). The cDNA was frozen at −80°C before use as the template for PCR or sequencing.

2.6. High-throughput T cell receptor sequencing

The amplification and sequencing protocols have been described previously (Robins et al, 2009, Marrero et al., 2013). Briefly, TCRβ CDR3 regions were amplified and sequenced by Adaptive Biotechnologies (Seattle, WA) by a multiplex PCR system designed to amplify all possible rearranged TCRβ CDR3 sequences from cDNA samples, using 35 forward primers specific for all Vβ gene segments and 13 reverse primers specific for all Jβ gene segments. The forward and reverse primers contain at their 5′ ends the universal forward and reverse primer sequences, respectively, compatible with the Illumina HiSeq cluster station solid-phase PCR system. The HiSeq system generates 60 bp reads, which cover the entire CDR3 lengths, sequencing from the J to the V region. The raw HiSeq sequence data were preprocessed to remove errors and to compress the data. Analysis of TCRβ sequences was conducted with the Adaptive TCR ImmunoSEQ assay. The TCRβ CDR3 region was defined according to the International ImMunoGeneTics (IMGT) collaboration, beginning with the second conserved cysteine encoded by the 3′ portion of the Vβ gene segment and ending with the conserved phenylalanine encoded by the 5′ portion of the Jβ gene segment. The number of nucleotides between these codons determines the length of the CDR3. A standard algorithm was used to identify which V, D, and J segments contributed to each TCRβ CDR3 sequence. The protocol was validated for the samples collected here by Adaptive Biotechnologies. Our dataset of PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ CDR3 sequences is available online at https://usegalaxy.org/u/islet-memory/h/pln-memory-cd4-t-cells at the Galaxy website.

2.7. TCR repertoire analysis (CDR3 length spectratype)

Repertoire analyses were performed using a modified protocol described by Pannetier et al. (1993). For CDR3 length spectratype, cDNA was amplified by PCR using forward primers specific for each of the eight Vβ gene families tested (Pannetier et al., 1993) and a common reverse Cβ145 primer (5’-CACTGATGTTCTGTGTGACA-3’), 5 min at 94°C for denaturing, and then 39 cycles of amplification (94°C for 45 s, 60°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 45 s) followed by a final elongation step at 72°C for 10 min. Using 2 µl of this PCR product as a template, run-off reactions were performed with internal fluorescent-conjugated (6-FAM) primers for the different Jβs (Pannetier et al., 1993), 30 s at 94°C for denaturing, and then 15 cycles of amplification (94°C for 45 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 1 min) and a final elongation step at 72°C for 5 min. All PCR reactions were performed on a 96-well GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems). The resulting products were then denatured in deionized formamide with a GeneScan 400 HD [ROX] size standard (Applied Biosystems). Fragment analysis was performed using ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyzer. The data were analyzed by GeneMapper Software V4.0 (Applied Biosystems) to obtain the CDR3 spectratype profile in individual mice. Primer sequences were synthesized at Operon Technologies (Alameda, CA). To compare the CDR3 spectratype profile between NOD and NOR mice, peaks within a particular Vβ-Jβ pairing were normalized prior to comparison, and then the normalized area of each peak in NOD mice was compared with that in NOR mice to determine the expansion of T cells within that rearrangement.

2.8. Distribution of frequencies and cut-off value

The raw frequencies of TCRβ CDR3 sequences were normalized by arithmetic mapping using a scale from 0 to 1, and a cut-off value to distinguish high and low-frequency clonotypes was calculated using the Z-score formula with a 99% confidence interval as described before (Marrero et al., 2013).

2.9. T cell proliferation assays

For induced proliferative responses to TCR-peptides, 6- to 10-wk-old female NOD mice were immunized subcutaneously with 7–14 nmol of each TCR-peptide emulsified in CFA (Difco, Detroit, MI). Draining (popliteal and inguinal) lymph nodes were removed 10 days later to prepare single-cell suspensions. Lymph node cells (4 × l05 cells per well) were cultured in 96-well microtiter plates in 200 µl of serum-free medium (HL-1, Bio-Whittaker), supplemented with 2 mM glutamine. Peptides were added at 14 µM final concentration. Proliferation was assayed by the addition of 1 µCi of [3H] thymidine for the last 16 h of a 5-day culture, and incorporation of label was measured by liquid scintillation counting.

2.10. Nasal instillation with TCR-peptides

Following anesthesia with Isoflurane, female NOD mice at 2 weeks of age were nasally instilled with 10 µg of either TCR-peptides (B1, B5 or TCR Vβ17) or HEL11–25 peptide in PBS in a total volume of 20 µl.

2.11. Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences between two groups were compared using the unpaired two-tailed t test. Statistical significance is shown as *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005, ***, p < 0.0005, and ****, p < 0.0001. Significance was determined using the data presented in each figure. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism software.

3. Results

3.1. The naturally selected TCRβ repertoire of PaLN-memory CD4+ T cells share similarities with the repertoire in the pancreas

In this study, we have examined ex-vivo the TCRβ repertoires of memory CD4+ T cells (CD4+CD44high) from PaLN of prediabetic and diabetic mice to determine whether the memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire in PaLN reflect the corresponding repertoire from the islets-infiltrating memory CD4+ T cells (Marrero et al., 2013). Unstimulated PaLN-CD4+CD44high T cells, hereafter referred as PaLN-memory CD4+ T cells, were sorted from individual prediabetic (n=6) and diabetic (n=6) female NOD mice and the TCRβ repertoire analyzed by high-throughput sequencing as described before (Marrero et al., 2013). A total of 6,364,571 and 7,157,810 productive TCRβ sequences were obtained from prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice, respectively. From these, 84,984 (range: 4,684–36,695) and 98,642 (range: 2,010–25,899) unique TCRβ clonotypes at the CDR3 amino acid level were assembled from prediabetic and diabetic mice, respectively (Table 1). Both prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice have a very similar degree of diversity in the PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire with Shannon entropy value close to 1 as reported by others for memory repertoires (Robins et al., 2009, Klarenbeek et al., 2010, Marrero et al., 2013, Estorninho et al., 2013). However in comparison to the memory CD4 repertoire in the pancreas (Marrero et al., 2013), the PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire is significantly more diverse (p=0.0005).

Table 1.

Summary of TCR CDR3β sequences of memory CD4+ T cells from PaLN of NOD mice

| Mouse # |

Total sequencesa |

Productive sequencesb |

Out of frame sequencesc |

Unique clonotypesd |

Entropye | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prediabetic | 1 | 1,383,340 | 1,290,284 | 91,804 | 4,684 | 0.910387 |

| 2 | 853,941 | 802,119 | 51,371 | 6,140 | 0.922921 | |

| 3 | 1,080,711 | 967,175 | 112,840 | 6,277 | 0.925919 | |

| 4 | 609,154 | 564,970 | 43,611 | 13,515 | 0.928411 | |

| 5 | 1,241,670 | 1,156,949 | 83,220 | 17,673 | 0.918004 | |

| 6 | 1,730,239 | 1,583,074 | 145,314 | 36,695 | 0.918892 | |

| Total | n = 6 | 6,899,055 | 6,364,571 | 528,160 | 84,984 | |

| Diabetic | 7 | 1,218,928 | 1,116,981 | 100,243 | 22,726 | 0.928054 |

| 8 | 1,223,723 | 1,139,121 | 82,845 | 20,199 | 0.930243 | |

| 9 | 2,004,499 | 1,871,072 | 131,793 | 25,899 | 0.893506 | |

| 10 | 587,048 | 548,887 | 37,683 | 2,010 | 0.901663 | |

| 11 | 1,815,300 | 1,644,275 | 167,816 | 16,374 | 0.924445 | |

| 12 | 910,306 | 837,474 | 72,023 | 11,434 | 0.931586 | |

| Total | n = 6 | 7,759,804 | 7,157,810 | 592,403 | 98,642 | |

Number of nucleotide sequences obtained.

Number of in-frame, read-through nucleotide sequences.

Number of out-of-frame nucleotide sequences

Number of unique amino acid sequences encoded by in-frame, read-through nucleotide sequences. Each unique amino acid sequence identified one unique clonotype.

Shannon’s entropy was used to quantify diversity of the TCRβ repertoire.

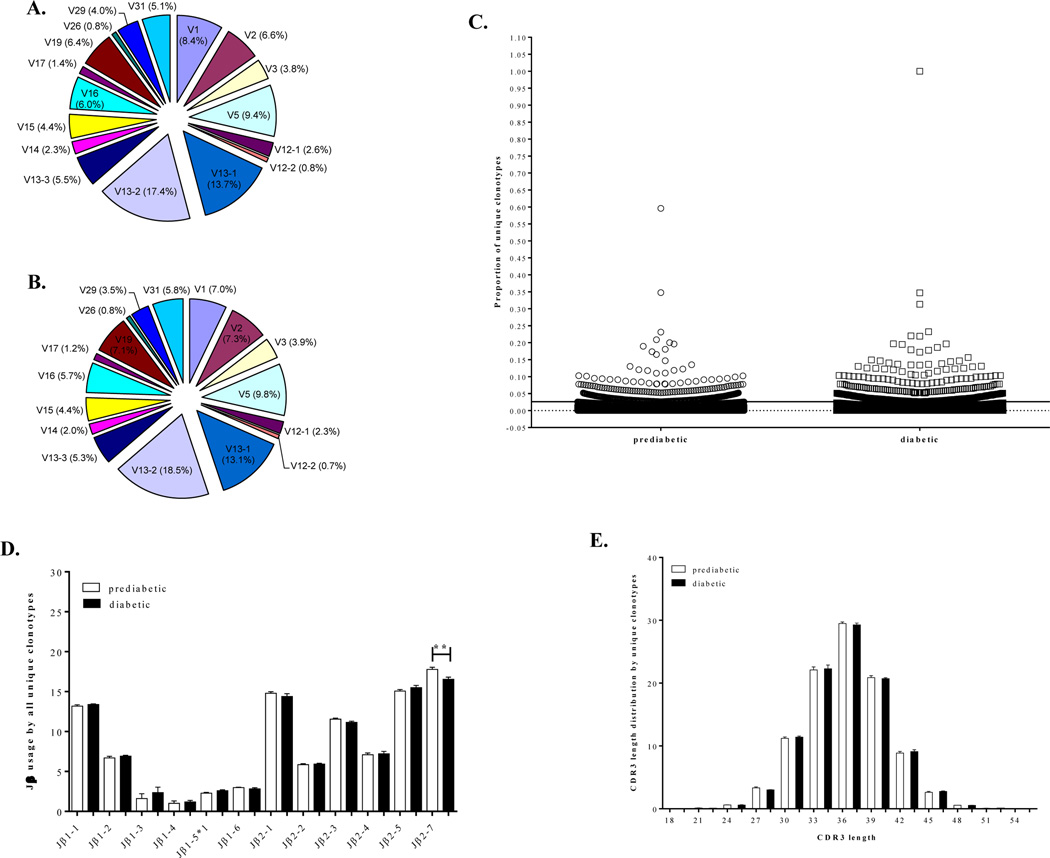

Surprisingly, TRBV usage by PLN-memory CD4+ T cells was remarkably similar in both prediabetic (Fig. 1A) and diabetic (Fig. 1B) NOD mice showing preferential usage of three TRBV gene segments. Thus, TRBV13-2 (Vβ8.2), TRBV13-1 (Vβ8.3), and TRBV5 (Vβ1) genes were expressed by 17.4%, 13.7% and 9.4%, respectively, of all unique clonotypes from prediabetic mice and by 18.5%, 13.1% and 9.8 % of all unique clonotypes from diabetic mice. Often, these TRBV genes were also dominantly used by individual mice (data not shown). These results indicate that the PLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire is highly restricted to use predominantly TRBV13-2, TRBV13-1 and TRBV5 in both prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice. Notably the TRBV genes TRBV1 (Vβ2), TRBV13-3 (Vβ8.1) and TRBV19 (Vβ6) that dominated the islet memory CD4+ repertoire were also among the most frequent TRBV genes used in PaLN (Marrero et al., 2013). Interestingly, when the total size of the repertoire (all productive CDR3β sequences) was considered in the analysis, TRBV1, TRBV19 and TRBV13-1 emerged as dominant TRBV genes in both prediabetic and diabetic mice suggesting that clones expressing these TRBV genes either accumulate or expanded in PaLN (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire is remarkably similar in both prediabetic and diabetic mice.

Unstimulated CD4+CD44high T cells from PaLNs of 10-week-old individual prediabetic (n=6) and newly diabetic (n=6) NOD female mice were sorted and subjected to high-throughput sequencing of the CDR3β regions as described in Materials and Methods. Frequency distribution of TRBV gene segment usage by all unique clonotypes from prediabetic (A) and diabetic (B) NOD mice is shown. PaLN-memory CD4+ T cells utilize similar TRBV gene segments in both prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice. Each TRBV gene segment is represented by a slice proportional to its average frequency. TRBV4, 10, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, and 30 genes were used at very low frequencies and are not shown in the graphs. (C) Scatter plot showing the normalized frequencies of all unique TCRβ clonotypes in prediabetic mice and diabetic mice. Clonotypes accounting for <0.02% and >0.02% of all CDR3β sequences were defined as rare and high-frequency clones, respectively. (D) Frequency distribution of TRBJ gene usage by all unique clonotypes from prediabetic and diabetic mice. Some TRBJ gene families were preferentially used by PaLN memory CD4+ T cells, but only the TRBJ2-7 segment was significantly more used by PaLN memory CD4+ T cells from prediabetic than from diabetic mice (**p= 0.08). Mean values with error bars representing ±SEM are shown for prediabetic (white bar) and diabetic (black bar) mice. (E) The distribution of CDR3β lengths for all unique clonotypes is shown. The most frequently observed length was 36 nucleotides. The CDR3 was defined as starting at the last cysteine encoded by the 3′ portion of the Vβ gene segment and ending at the phenylalanine in the conserved TRBJ segment motif FGXG. Mean values with error bars representing ±SEM are shown for prediabetic (white bar) and diabetic (black bar) mice.

A considerable proportion of the PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoires is consisted of rare low frequency clonotypes, as reported for the islet repertoire (Marrero et al., 2013). Rare clonotypes represented approximately 97.7% and 96.7% of all clonotypes in the CD4 memory compartment in PaLN of prediabetic and diabetic mice, respectively (Fig. 1C). Similar findings have also been reported for human memory T cells (Freeman et al., 2009, Klarenbeek et al., 2010). Furthermore, the frequency of TRBJ usage among PaLN-memory CD4+ T cell clonotypes was also comparable between prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice (Fig. 1D). Both groups of mice utilized preferentially TRBJ 2–7, 2–5, 2-1 and 1-1 indicating a bias in the usage of specific TRBJ gene segments among PaLN-memory CD4+ T cells. These TRBJ genes have recently been reported as the most common genes used by islet-infiltrating T cells (Toivonen et al., 2015). Moreover, the distribution of CDR3β lengths was nearly identical in the prediabetic and diabetic mice, showing a typical Gaussian-like distribution. Most CDR3 sequences in both groups were 36 nucleotides in length ranging from 18 to 54 nucleotides for all unique clonotypes (Fig. 1E). These results indicate high diversity within the memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire in the PaLNs.

Overall, our data show that both PaLN- and islet-infiltrating memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoires are diverse and composed mainly for rare clonotypes. Both repertoires expressed dominant TRBV gene segments that are equally used in both prediabetic and diabetic mice, suggesting that clonotypes using the dominant TRBV genes might be preferentially selected in the repertoire of memory CD4+ T cells in the NOD mice and may represent islet-antigen reactive T cells.

Consistent with the islet-reactivity, we found several clones with CDR3β sequences identical to previously published diabetes-related TCRβ sequences. Notably, 82% of these clones utilized one of the dominant TRBV genes, some of these clones were shared between three or more mice and others were part of the islet-infiltrating memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire (Supplemental Table 1). Interestingly, we found 24 clones with CDR3β sequences matching those reported to be part of TCRs of islet-infiltrating T cells, islet-infiltrating CD4+ T cells or PaLN-T cells of prediabetic NOD mice (Supplemental Table 1) (Drexler et al., 1993; Berschick et al., 1993; Sarukhan et al., 1994; Baker et al., 2002; Toivonen et al., 2015). Most of these sequences identified rare clonotypes, however, eight of them were among high frequency clonotypes in at least one mouse. Furthermore, we found 32 clones with CDR3β sequences matching sequences reported to bind biologically important epitopes (Table 2): 12 matching sequences of CD8 T cells reactive to islet-specific glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit-related protein (IGRP) (Wong et al., 2006, 2007); 8 matching sequences of islet-infiltrating CD4 T cells specific for a mimetic epitope recognized by the BDC2.5 clonotypic TCR (Li et al., 2009); 4 reported in clones reactive to glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD)65 (Quinn et al., 2006; Li et al., 2008), and 5 reactive against insulin B:9–23 (Simone et al., 1997; Zhang et al. 2009). Other clones with sequences matching TCRs of clones with islet reactivity were also found (Nakano et al. 1991; Nagata et al., 1992; Tikochinski et al., 2009). All of these clones were among rare clonotypes.

Table 2.

CDR3β sequences from PaLN-memory CD4+ T cells matching CDR3 sequences previously associated with diabetes-related autoantigens.

| Islet specificity | CDR3 sequence | V gene | J gene | # prediabetic mice |

# diabetic mice |

Found in pancreas |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGRP | WDWEYEQYF | 4 | 2–7 | 1 | 0 | Wong et al., 2006 | |

| DDNYEQYF | 13–3 | 2–7 | 1 | 0 | X | ||

| DGTYEQYF | 13–3 | 2–7 | 0 | 1 | |||

| GDISYEQYF | 13–3 | 2–7 | 1 | 0 | |||

| KTDSYEQYF | 13–3 | 2–7 | 1 | 0 | |||

| DSQNTLYF | 13–3 | 2–4 | 2 | 2 | X | Wong et al., 2007 | |

| DPENTLYF | 13–3 | 2–4 | 1 | 0 | |||

| DGSYEQYF | 13–3 | 2–7 | 2 | 3 | |||

| DAQYEQYF | 13–3 | 2–7 | 1 | 3 | |||

| DPKYEQYF | 13–3 | 2–7 | 1 | 1 | X | ||

| DRYEQYF | 13–3 | 2–7 | 1 | 1 | |||

| GTDYEQYF | 13–3 | 2–7 | 1 | ||||

| GAD65 clones | RDWGYEQYF | 2 | 2–7 | 0 | 1 | Quinn et al., 2006 | |

| QRGANTEVFF | 5 | 1–1 | 1 | 0 | Li et al., 2008 | ||

| PRDSAETLYF | 5 | 2–3 | 0 | 1 | |||

| GDAGGAQDTQYF | 13–2 | 2–5 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Insulin B9:23 12–4.4 8–1.1 8–1.9 | IRGTEVFF | 19 | 1–1 | 3 | 1 | X | Zhang et al., 2009 |

| QDTNTGQLYF | 5 | 2–2 | 1 | 2 | |||

| LGWGDEQY | 16 | 2–7 | 1 | 0 | Simone et al., 1997 | ||

| PDNANTE | 26 | 1–1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| BDC2.5 TCR Peptide mimotope | LNTEVFF | 15 | 1–1 | Public | Public | X | Li et al., 2009 |

| LGGNTEVFF | 15 | 1–1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| LGGYAEQFF | 15 | 2–1 | 0 | 3 | X | ||

| LGQQDTQYF | 15 | 2–5 | 1 | ||||

| TGGDTQYF | 15 | 2–5 | 1 | ||||

| LAQGQGYEQYF | 15 | 2–7 | 1 | ||||

| LLGSYEQYF | 15 | 2–7 | 1 | 1 | |||

| RDSSYEQYF | 15 | 2–7 | Public | 3 | X | ||

| Hsp (p277) clone | LGGNQDTQYF | 15 | 2–5 | 0 | 1 | X | Tikochinski et al., 2009 |

| 4-1-K.1 clone | GGYEQYF | 13–2 | 2–7 | Public | 3 | X | Nakano et al., 1991 |

| 4-1-E.2 clone | RLGNQDTQYF | 15 | 2–5 | 0 | 3 | X | |

| NY4.1 TCR | LGTGGYAEQFF | 16 | 2–1 | 2 | 1 | Nagata et al., 1992 | |

These results suggest an autoimmune response in the pancreas by memory CD4+ T cells against a broader range of β cell autoantigens primed in PaLN in both prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice.

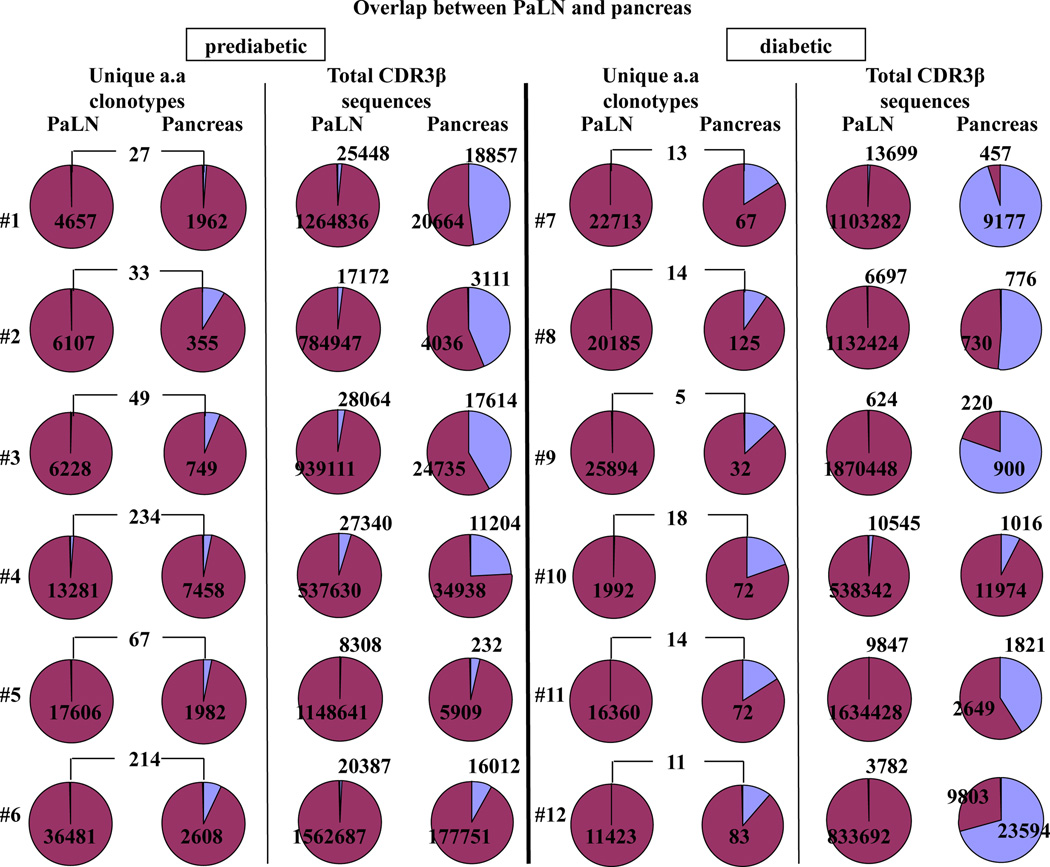

3.2. Limited overlap of CDR3β sequences derived from memory CD4+ T cells between PaLN and pancreas

To evaluate the extent of TCRβ overlap between memory CD4+ clonotypes present in PaLN and pancreas, we compared the CDR3 sequences retrieved from both PaLN and islets of each individual mouse. Because some TRBV segments have very similar sequences and more than one TRBV segment can contribute to the same CDR3 amino acid sequence, we analyzed the overlap of CDR3 amino acid sequences carrying the same TRBV/TRBJ pairing. The number of unique clonotypes that overlap between PaLN and pancreas ranged from 27 to 234 among prediabetic mice (Fig. 2, first column) and from 5 to 18 among diabetic mice (Fig. 2, third column). Only 0.7% (range: 0.4–1.7%) and 0.1% (range: 0.02–0.9%) of the unique clonotypes in PaLN of prediabetic and diabetic mice, respectively, were also present in the pancreas memory repertoire. While 4% (range: 1.4–8.5%) and 17% (range: 12–21%) of the unique clonotypes in the pancreas of prediabetic and diabetic mice, respectively, were also present in the PaLN memory repertoire, confirming the priming of these overlapping clonotypes in PaLN.

Figure 2. Overlapping clonotypes between PaLN and pancreas represent a small fraction of total clonotypes but constitute a significant portion of the total memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire in the pancreas.

Left panel: for each of the six prediabetic mice, the proportion of unique clonotypes that are overlapped between PaLN and pancreas and the proportion of the total memory TCRβ repertoire attributable to those overlapping clonotypes are shown. Right panel: for each of the six diabetic mice, the proportion of unique clonotypes that are overlapped between PaLN and pancreas and the proportion of the total memory TCRβ repertoire attributable to those overlapping clonotypes are shown.

We then determined the proportion of the total memory TCRβ repertoire (total CDR3 sequences) in PaLN and pancreas represented by overlapping sequences. In prediabetic mice, overlapping sequences comprise 2% (range: 0.7–4.8%) and 20% (range: 3.8–47.7%) of the total memory TCRβ repertoire in PaLN and pancreas, respectively (Fig. 2, second column). In marked contrast, 59% (range: 8.4–95.3%) of the total memory TCRβ repertoire in the pancreas of diabetic mice were represented by overlapping sequences, while these sequences represented only 0.6% (range: 0.04–1.9%) in PaLN (Fig. 2, four column), suggesting expansion of dominant clonotypes in the pancreas that might be involved in diabetes development. Within the pancreas, 4.6% and 39.6% of the total memory TCRβ repertoire were represented by overlapping sequences between individual prediabetic and diabetic mice, respectively (data not shown).

Next, we examined whether high-frequency clonotypes contribute to overlapping sequences between PaLN and pancreas. In prediabetic mice, 12.5% (range: 0–24.5%) and 10.5% (range: 0–25.9%) of overlapping clonotypes were high-frequency clonotypes in PaLN and pancreas, respectively. These high-frequency clonotypes contribute to 38.4% (range: 0–78.9%) and 48.5% (range: 0–98.2%) of the overlapping sequences in PaLN and pancreas, respectively. Remarkably, high-frequency clonotypes in diabetic mice contribute to 61.5% (range: 0–81.3%) and 87.6% (range: 37.2–99.3%) of overlapping sequences in PaLN and pancreas, respectively, although they only represent 17.3% (range: 0–33.3%) and 31.3% (range: 0–54.5%) of overlapping clonotypes in PaLN and pancreas.

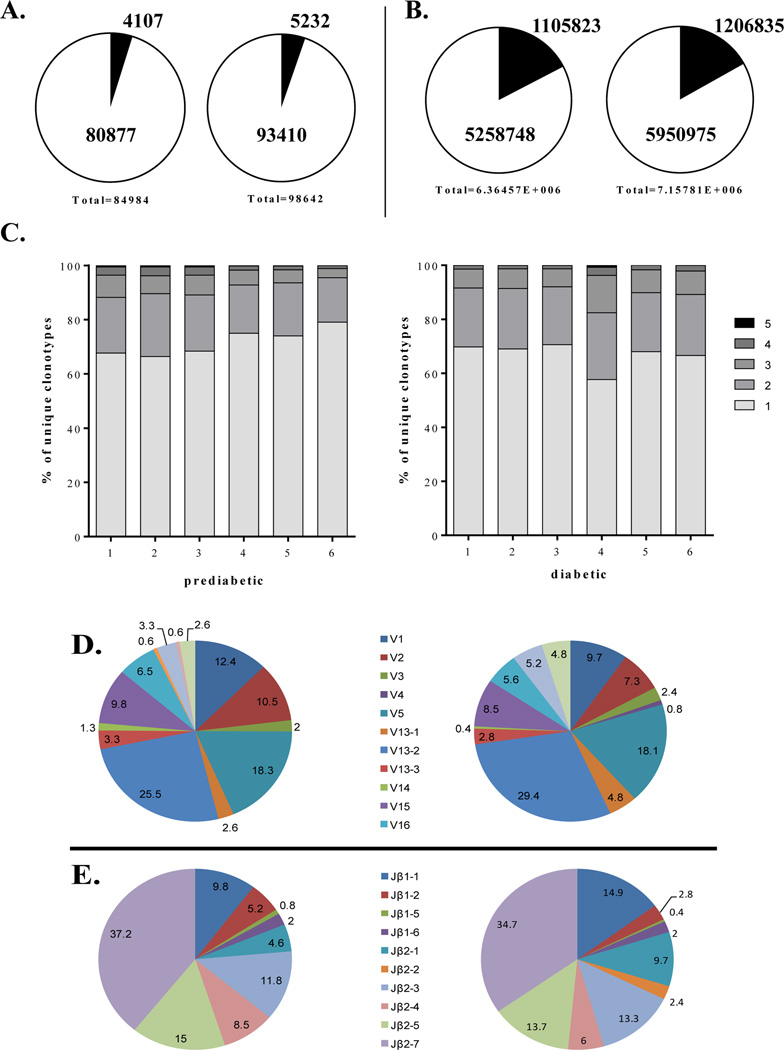

3.3. Presence of public clonotypes within the PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire

Generally, T cell responses include a heterogeneous repertoire composed of both public (TCRs shared among multiple individuals) and private repertoires. Here, public clonotypes were defined as those TCRβ clonotypes shared by 4 out of 6 mice (67%) within each group that express identical CDR3 at the amino acid level within the same Vβ-Jβ pairing. To evaluate the degree of TCRβ sharing among individual mice of the same groups, we compared CDR3 sequences from PaLN of individual mice within each group. We found 4,107 distinct unique clonotypes shared among prediabetic mice, which accounted for 4.8% of all 84,984 unique clonotypes in this group. A total of 5,232 distinct unique clonotypes were shared among diabetic mice representing 5.3% of all 98,642 unique clonotypes (Fig. 3A). These shared clonotypes contributed to 21% and 20.3% of the total memory TCRβ repertoire (total CDR3β sequences) in PaLN of prediabetic and diabetic mice, respectively (Fig. 3B), indicating that the PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire of individual mice is fundamentally private.

Figure 3. TCRβ sharing within the PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire in the NOD mice.

(A) Shared clonotypes within the prediabetic (left) and diabetic (right) PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoires are shown. (B) Proportion of the total memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoires attributable to sharing clonotypes between prediabetic (left) and diabetic (right) mice. (C) Proportion of unique clonotypes of prediabetic (left) and diabetic (right) mice that were shared with one, two, three, four, five, or all six mice. (D) The average frequency of TRBV gene segment usage for public clonotypes is shown. Each TRBV gene segment is represented by a slice proportional to its frequency. (E) The average frequency of Jβ usage among public clonotypes is shown.

Among individual mice, the proportion of unique clonotypes owing to shared clonotypes range from 8% (3,000/36,695) to 14% (669/4,684) in prediabetic mice, and from 11% (2,770/25,899) to 15% (303/2,010) in diabetic mice. No significant differences were found when the number of shared clonotypes and the proportion of total unique clonotypes attributable to those clonotypes were compared between prediabetic and diabetic mice (Table 3). Thus, there was a low degree of clonotype sharing within the PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire in both prediabetic and diabetic mice as previously reported for islet-infiltrating memory CD4+ T cells (Marrero et al., 2013).

Table 3.

Overlap within the PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire in prediabetic and diabetic female NOD mice.

| Prediabetic mice | Diabetic mice | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| Overlapping clonotypesa | 669 | 830 | 817 | 1,758 | 2,069 | 3,000 | 2,591 | 2,505 | 2,770 | 303 | 2,105 | 1,626 |

| Proportion (%)b | 14.3 | 13.5 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 11.7 | 8.2 | 11.4 | 12.4 | 10.7 | 15.1 | 12.9 | 14.2 |

| Shared withc | ||||||||||||

| 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | 20 | 27 | 25 | 27 | 30 | 31 | 34 | 30 | 34 | 9 | 35 | 32 |

| 3 | 55 | 55 | 60 | 97 | 99 | 102 | 182 | 183 | 185 | 42 | 176 | 141 |

| 2 | 137 | 193 | 169 | 332 | 405 | 491 | 565 | 561 | 592 | 75 | 461 | 368 |

| 1 | 453 | 551 | 559 | 1,298 | 1,531 | 2,372 | 1,808 | 1,729 | 1,957 | 175 | 1,431 | 1,083 |

| Publicd | 79 | 86 | 89 | 128 | 133 | 137 | 206 | 202 | 221 | 53 | 213 | 175 |

| Clonotype sizee | 37,248 | 14,254 | 22,751 | 12,270 | 18,066 | 8,365 | 18,189 | 18,997 | 29,869 | 13,978 | 38,333 | 17,008 |

| Proportion (%)f | 2.9 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.0 |

Numbers of unique clonotypes shared with other mice (identical CDR3β amino acid sequence within the same Vβ-Jβ pairing).

Proportion of total unique clonotypes that was attributable to overlapping clonotypes.

Number of overlapping clonotypes shared with one, two, three, four, or five mice within the prediabetic and diabetic group.

Public clonotypes are defined as those clonotypes present in at least 4 out of 6 mice (67%) that express identical CDR3 amino acid sequence within the same Vβ-Jβ pairing.

CDR3β sequences of public clonotypes.

Proportion of total memory repertoires (total CDR3 sequences) that was attributable to public clonotypes.

To determine the extent of clonotype sharing between mice, we calculated the proportion of the shared repertoire in individual mouse that was attributable to clonotypes shared with one, two, three, four, or five mice within the prediabetic and diabetic group. Most of the clonotypes were non-public, i.e. so-called private that were not shared with other mice. Clonotypes shared between two individual mice contributed to a large proportion of the sharing repertoire in a mouse (Table 3) that ranged between 66.4% and 79.1% (average: 71.6%) in prediabetic mice, and between 57.8 and 70.7% (average: 67%) in diabetic mice (Fig. 3C). Toivonen et al. (2015) have recently reported sharing of clones in the islet repertoire of 7-week-old NOD mice between two individual mice but not between all three mice studied. In contrast, we found several public clonotypes in the PaLN repertoire present in multiple mice in each group.

A total of 367 public clonotypes were identified that contribute to approximately 2% of the total repertoire in PaLN of both prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice (Table 3). Among individual mice, the number of public clonotypes varied from 79 to 137 in prediabetic mice, and from 53 to 221 in diabetic mice. There is a positive correlation between the number of sharing clonotypes and the number of public clonotypes in both groups of mice (r2= 0.8722, p= 0.0064 in prediabetic, and r2=0.9411, p=0.0013 in diabetic). The majority of these public clonotypes are rare clones, only 5 of them were high frequency clones in at least one mouse (Table 4).

Table 4.

CDR3 sequences of public clonotypes in the PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire of NOD micea

| CDR3 | V gene | J gene | # prediabetic |

# diabetic |

Found in pancreas |

CDR3 | V gene | J gene | # prediabetic |

# diabetic |

Found in pancreas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADRNTEVFF | 1 | 1–1 | 5/6 | 4/6 | XC | GDAGSAETLYF | 13–2 | 2–3 | 3/6 | 5/6 | X |

| ADRGSDYTF | 1 | 1–2 | 5/6 | No | GDAGGQNTLYF | 13–2 | 2–4 | 5/6 | 2/6 | ||

| ADSQNTLYF | 1 | 2–4 | 5/6 | 3/6 | X | GDGGSQNTLYF | 13–2 | 2–4 | 5/6 | 4/6 | |

| AGGNQDTQYF | 1 | 2–5 | 3/6 | 5/6 | GDWGQDTQYF | 13–2 | 2–5 | 6/6 | 3/6 | X | |

| ADSYEQYF | 1 | 2–7 | 4/6 | 5/6 | X | GGQQDTQYF | 13–2 | 2–5 | 6/6 | 2/6 | |

| GTGGYEQYF | 1 | 2–7 | 4/6 | 5/6 | X | GDAGYEQYF | 13–2 | 2–7 | 5/6 | 3/6 | X |

| QDRGNTEVFF | 2 | 1–1 | 2/6 | 5/6 | GDSSYEQYFb | 13–2 | 2–7 | 4/6 | 2/6 | X | |

| QEAQYNSLYF | 2 | 1–6 | 5/6 | 3/6 | X | GDYEQYF | 13–2 | 2–7 | 4/6 | 5/6 | |

| QDSAETLYF | 2 | 2–3 | 5/6 | 3/6 | GGYEQYFb | 13–2 | 2–7 | 4/6 | 3/6 | X | |

| QEERGPSAETLYF | 2 | 2–3 | 5/6 | 3/6 | X | GGTGGYEQYF | 13–2 | 2–7 | 3/6 | 5/6 | |

| QDWGQDTQYF | 2 | 2–5 | 4/6 | 5/6 | LGQYEQYF | 14 | 2–7 | No | 5/6 | ||

| QDSSYEQYF | 2 | 2–7 | 5/6 | 4/6 | LQGANTEVFF | 15 | 1–1 | 2/6 | 5/6 | ||

| QDWGGYEQYF | 2 | 2–7 | 5/6 | 4/6 | LNTEVFFb | 15 | 1–1 | 4/6 | 4/6 | X | |

| QDRGNTEVFF | 5 | 1–1 | 4/6 | 5/6 | PGQNTEVFF | 15 | 1–1 | 2/6 | 5/6 | ||

| QGTDTEVFF | 5 | 1–1 | 5/6 | 3/6 | LGDAEQFF | 15 | 2–1 | 5/6 | 5/6 | X | |

| QGQGTEVFF | 5 | 1–1 | No | 5/6 | RQGPYAEQFF | 15 | 2–1 | 2/6 | 5/6 | X | |

| QGQGANTEVFFb | 5 | 1–1 | 3/6 | 4/6 | LDSSAETLYF | 15 | 2–3 | 5/6 | No | ||

| QDSSYNSLYF | 5 | 1–6 | 4/6 | 5/6 | LGSQNTLYF | 15 | 2–4 | 5/6 | 3/6 | ||

| QTGGYAEQFF | 5 | 2–1 | 5/6 | 4/6 | LGGQNTLYF | 15 | 2–4 | 5/6 | No | ||

| QQGNTGQLYFb | 5 | 2–2 | 5/6 | 5/6 | X | STGGYEQYF | 15 | 2–7 | 2/6 | 6/6 | |

| QDSAETLYF | 5 | 2–3 | 5/6 | 2/6 | LNWGDSYEQYF | 15 | 2–7 | No | 5/6 | X | |

| QDWGQNTLb | 5 | 2–4 | 4/6 | 2/6 | RDSSYEQYFb | 15 | 2–7 | 4/6 | 3/6 | X | |

| QDWGQDTQYF | 5 | 2–5 | 4/6 | 5/6 | RLGGYEQYF | 15 | 2–7 | No | 5/6 | X | |

| QEDTQYF | 5 | 2–5 | 5/6 | No | PGQNTEVFF | 16 | 1–1 | 4/6 | 2/6 | ||

| QTGGQDTQYF | 5 | 2–5 | 5/6 | 3/6 | LRQGDTEVFFbd | 16 | 1–1 | No | 4/6 | ||

| QDRGYEQYF | 5 | 2–7 | 5/6 | 2/6 | LGGQNTLYF | 16 | 2–4 | 6/6 | 5/6 | ||

| QDSSYEQYF | 5 | 2–7 | 5/6 | 3/6 | LGQYEQYF | 16 | 2–7 | 5/6 | 4/6 | X | |

| QDWGGYEQYF | 5 | 2–7 | 5/6 | 4/6 | X | ILGGYAEQFF | 19 | 2–1 | 2/6 | 5/6 | X |

| QGTGGYEQYF | 5 | 2–7 | 4/6 | 5/6 | ISAETLYF | 19 | 2–3 | 5/6 | 3/6 | X | |

| QVGYEQYFbd | 5 | 2–7 | 3/6 | 4/6 | RLGVNQDTQYF | 19 | 2–5 | 5/6 | No | ||

| PGTGGYEQYF | 5 | 2–7 | 5/6 | 4/6 | ILGGSYEQYF | 19 | 2–7 | 2/6 | 5/6 | ||

| GTANSDYTF | 13–1 | 1–2 | 3/6 | 6/6 | X | IRTGGYEQYF | 19 | 2–7 | No | 5/6 | X |

| GGTGNTEVFF | 13–2 | 1–1 | No | 5/6 | IGTGGYEQYF | 19 | 2–7 | 2/6 | 5/6 | X | |

| GGTTNSDYTF | 13–2 | 1–2 | 3/6 | 5/6 | IGTGSYEQYFbd | 19 | 2–7 | 3/6 | 4/6 | X | |

| GGYNYAEQFF | 13–2 | 2–1 | 6/6 | 4/6 | X | IGWGSSYEQYFbd | 19 | 2–7 | 3/6 | 5/6 | X |

| GDLGGYAEQFF | 13–2 | 2–1 | No | 5/6 | IRQYEQYF | 19 | 2–7 | 5/6 | No | X | |

| GDWGNTGQLYF | 13–2 | 2–2 | 5/6 | 2/6 | X | ISGGYEQYFbd | 19 | 2–7 | 2/6 | 4/6 | X |

| GDAGAETLYF | 13–2 | 2–3 | 4/6e | 5/6e | X | LGNQDTQYF | 31 | 2–5 | 4/6 | 5/6 | X |

| GDAGASAETLYF | 13–2 | 2–3 | No | 5/6 | LGGYEQYF | 31 | 2–7 | 5/6 | 2/6 |

Only the 12 public clonotypes with CDR3 sequences matching sequences reported as well as those found in at least 5 mice in each group are shown.

CDR3 sequences matching those reported in the literature.

CDR3 sequences amplified from islet-infiltrating memory CD4+ T cells in previous study (Marrero et al., 2013).

These public clonotypes are high frequency clones found in at least one mouse.

We identified three groups of public clonotypes: (1) those that are public in both prediabetic and diabetic mice (34 out of 367, 9.3%); (2) those clonotypes that are public only in prediabetic (83, 22.6%) or diabetic (128, 34.9%) mice, but are also found in the other group, and (3) those clonotypes that are public and found exclusively in prediabetic (37, 10.1%) or diabetic (85, 23.2%) mice. Interestingly, 28.3% of these public clonotypes (104 out of 367) were previously identified by us within the islet-infiltrating memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire. These data suggest that these public clonotypes are dynamic and they may fluctuate over time during disease progression, but certain clonotypes persist indicating persistent antigenic stimulation.

The public clonotypes had very similar TRBV usage in both prediabetic and diabetic mice (Fig. 3D). TRBV13-2, TRBV5, TRBV1, TRBV2 and TRBV15 are the five most frequent TRBV genes expressed by public clonotypes representing 76.5% and 73% of the public repertoire in prediabetic and diabetic mice, respectively. Furthermore, there was a distinct preferential usage of the Jβ2.7 gene (Fig. 3E); although other 9 different Jβ gene segments were also utilized by public clonotypes. Collectively, these results reveal that there is a biased TCRβ repertoire that encode the CDR3 of the public β chains, which is characterized by preferential usage of TRBV13-2, TRBV5, TRBV1, TRBV2 and TRBV15 in rearrangement with TRBJ2–7. Cross-comparison of our data with previously reported sequences showed that nine public clonotypes had CDR3 sequences matching sequences reported in pancreatic islets of prediabetic NOD mice (Suplemental Table 1) (Drexler et al., 1993; Sarukhan et al., 1994; Baker et al., 2002; Toivonen et al. (2015), and other three matching sequences associated with islet reactivity (Table 2) (Nakano et al. 1991; Li et al., 2009). These public clonotypes as well as those shared by at least 5 mice in each group are shown in Table 4.

We further examined whether the TRBV genes used more frequently by public clonotypes are associated with autoimmune diabetes. Thus, CDR3 length spectratyping or immunoscope analysis was performed on PaLN of female 10-week-old NOD mice and compared with the CDR3 spectratype of age-matched diabetes-resistant female NOR mice. Total mRNA was extracted from the cells and Vβ-Cβ products amplified by RT-PCR using primers specific for the TCR Vβ chains expressed by public clonotypes. Each Vβ-Cβ product was further subjected to a run-off PCR using fluorescent Jβ primers in order to have the TCR spectratype for the Vβ-Jβ pairing used by public clonotypes. Although the spectratype of each Vβ-Jβ pairing tested displayed a Gaussian-like distribution in PaLN of both NOD and NOR mice (Supplemental Figure 2), we found that 36 CDR3 peaks within eight different Vβ (TRBV) genes are significantly larger in the NOD mice compared to NOR mice. Furthermore, expansion of these T cells were observed in almost all NOD mice suggesting dominant responses. Interestingly, Vβ8.2 (TRBV13-2) was the most perturbed of the TRBV genes tested with 13 distinct CDR3 peaks that are significantly larger in NOD mice (Table 5). Vβ11 (TRBV16) is significantly different at six peaks, while Vβ4 (TRBV2) and Vβ12 (TRBV15) are significantly different at four peaks. The Vβ1 (TRBV5), Vβ2 (TRBV1), Vβ6 (TRBV19), and Vβ8.1 (TRBV13-3) are significantly different at three or fewer peaks. These data are consistent with our previous report indicating that both Vβ8.2 (TRBV13-2) and Vβ8.1 (TRBV13-3) are highly perturbed in 10-week-old and diabetic NOD mice compared with 4-week-old NOD mice (Marrero et al., 2012). The comparisons of CDR3 length spectratypes between NOD and NOR mice for the Vβ (TRBV) tested are shown in Supplemental Fig. 2.

Table 5.

Analysis by CDR3 length spectratype of PaLN cells from NOD and NOR micea

| TRBV gene | Vβ family |

Jβ family |

Total of expanded peaksc |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jβ1–1 | Jβ1–2 | Jβ1–5 | Jβ1–6 | Jβ2–1 | Jβ2–2 | Jβ2–3 | Jβ2–4 | Jβ2–5 | Jβ2–7 | |||

| TRBV5 | Vβ1 | 1b | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | ||||||

| TRBV1 | Vβ2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | ||

| TRBV2 | Vp4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |||||

| TRBV19 | Vβ6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| TRBV13-3 | Vβ8.1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| TRBV13-2 | Vβ8.2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 13 |

| TRBV16 | Vβ11 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | ||||

| TRBV15 | Vβ12 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| Total | 6 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 36 | |

Only the TCR Vβ chains used more frequently by public clonotypes are shown.

Number of peaks within that specific Vβ-Jβ spectratype that are significantly expanded in PaLN of the NOD mice compared with NOR mice.

Total number of peaks within the entire spectratype for that specific TCR Vβ chain that are significantly expanded in the NOD mice compared with NOR mice.

10-wk-old NOD mice, n=10–17; 10-wk-old NOR mice, n=5–10.

Collectively, our results show that several public clonotypes were found between different mice within the PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire, suggesting that common antigens may trigger their selection in NOD mice that contribute to the development of T1D. These public TCRβ sequences can potentially be used as biomarkers to identify pathogenic T cells.

3.4. Convergent recombination appear to play an important role in sharing of TCRβ sequences

To examine whether convergent recombination contributes to TCR sharing, we analyzed the numbers of different nucleotide sequences that converge to encode the same CDR3β amino acid sequence in those clonotypes shared between PaLN and pancreas and public clonotypes. Our analysis revealed that 68% (424 out of 624) and 40% (30 out of 75) of overlapping clonotypes between PaLN and pancreas of prediabetic and diabetic mice, respectively, were assembled from multiple nucleotide sequences encoding the same CDR3β amino acid sequence. The remaining overlapping clonotypes result from a single unique nucleotide sequence, i.e. 32% and 60% of overlapping clonotypes in prediabetic and diabetic mice, respectively. Moreover, the CDR3β amino acid sequences of public clonotypes were encoded by different nucleotide sequences. For example, the four public clonotypes present in all six prediabetic mice, TRBV13-2/TRBJ2-1 (CASGGYNYAEQFF), TRBV13-2/TRBJ2–5 (CASGDWGQDTQYF), TRBV13-2/TRBJ2–5 (CASGGQQDTQYF) and TRBV16/TRBJ2–4 (CASSLGGQNTLYF) were encoded by seven, ten, six and seven different nucleotide sequences, respectively. Similarly, the two public clonotypes present in all six diabetic mice, TRBV13-1/TRBJ1–2 (CASSGTANSDYTF) and TRBV15/TRBJ2–7 (CASSSTGGYEQYF) were encoded by six and 10 different nucleotide sequences, respectively.

Collectively, these findings indicate that convergent recombination is a major player in driving TCRβ sharing in the memory CD4 T cell repertoire.

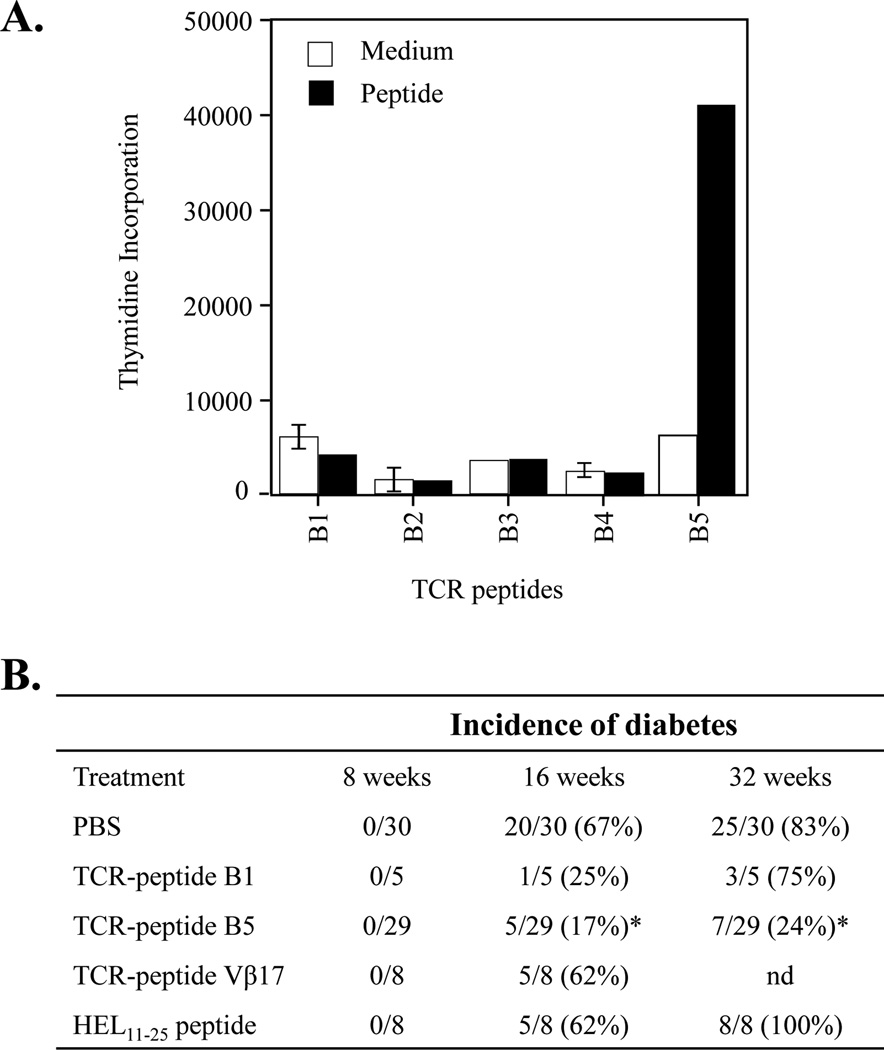

3.5. Nasal instillation of female NOD mice with TCR-peptide B5 significantly prevents spontaneous diabetes

Our data suggest that memory CD4+ T cells expressing TRBV13-2 (Vβ8.2) could play an important role in the progression of T1D in the NOD mice. First, TRBV13-2 gene is dominant within the PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire in both prediabetic and diabetic mice. Second, TRBV13-2 is also preferentially used by public clonotypes. Third, the CDR3 length spectratype of TCR Vβ8.2 is more perturbed in NOD mice compared to NOR mice and showed a significant increase in total perturbation index in PaLN of NOD mice at 10 weeks of age and at T1D onset compared to 4 weeks of age (Marrero et al., 2012). These findings together with previous results showing that priming with the TCR-peptide B5 derived from the TCR Vβ8.2 chain protect from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) and collagen II-induced arthritis (Kumar et al., 1995, Kumar et al., 1997; Kumar et al., 2001; Tang et al., 2007; Smith and Kumar, 2008; Smith et al., 2010) prompted us to investigate whether Vβ8.2+ memory CD4+ T cells have a role in T1D in the NOD mice using TCR-peptide based vaccination approach.

First, we determined whether splenocytes in the NOD mice could also be stimulate by TCR Vβ8.2-derived peptides. We tested the immunogenicity potential of five overlapping TCR-peptides (26–30 mers) covering the entire variable region of the TCR Vβ8.2 chain. To this purpose, female NOD mice were immunized subcutaneously with 7 nmol of individual peptides in CFA. After ten days, proliferative responses in the draining lymph node T cells were examined in response to an in vitro challenge with 14 µM of the corresponding peptide. Only the TCR peptide B5 (aa 76–101) induces proliferative responses in NOD mice (Fig. 4A). There was no proliferative response to the other four TCR Vβ8.2 peptides. Anti-CD4 mAb was able to block this response, whereas anti-CD8 mAb had no significant effect (data not shown) indicating that CD4+ T cells are activated by TCR-peptide B5. These results indicate that TCR B5-reactive CD4+ T cells are present in the NOD mice.

Figure 4. TCR peptide B5 from the Vβ8.2 chain induces protection from T1D.

(A) Only one peptide from the Vβ8.2 chain, TCR-peptide B5 (aa 76–101), induced significant proliferative response in lymph node cells of NOD mice. Groups of female NOD mice (three mice in each group) were immunized subcutaneously with 7–14 nmol of each of the five overlapping TCR-peptides (B1-B5) emulsified in CFA. After 10 days, draining lymph nodes cells were isolated and proliferative T-cell response to the immunizing peptide at a concentration of 14 µM were measured. [3H] thymidine incorporation was determined by liquid scintillation analysis and is expressed as cpm. The amino acid sequences of the TCR peptides are given in Material and Methods. Bar indicates stimulation conditions for draining lymph nodes cells: white bars, cell alone as control, and black bars, different TCR-peptides derived from TCR Vβ8.2 chain (B1, B2, B3, B4, and B5). The data shown represent the mean ± SEM for cpm determinations made on triplicate wells. This experiment is representative of two separate experiments. (B) Nasal priming of NOD mice with TCR-peptide B5 protects from T1D. Groups of female NOD mice at 2 weeks of age were nasally instilled with PBS, HEL11–25 peptide (10 µg/mouse), and TCR-peptides B1, B5 or TCR Vβ17 (10 µg/mouse of each peptide) in PBS in a total volume of 20 µl. Diabetes was monitored until 32 weeks of age. Vaccination of NOD mice with PBS, TCR-peptide B1, TCR Vβ17 peptide and HEL11–25 peptide had no significant effect on diabetes onset. In contrast, vaccination with TCR-peptide B5 significantly delayed diabetes onset (* p<0.0001 between the control (PBS or B1) versus TCR-peptide B5). Data from two different experiments are summarized in this table.

Next we investigated whether priming of TCR-peptide B5-reactive regulatory CD4+ T cells has any influence on the course of T1D in the NOD mice. To avoid nonspecific effects of adjuvants on the development of diabetes, we used nasal instillation of peptides diluted in PBS. At 2 week old, each female NOD mouse was nasally instilled with either 10 µg of TCR-peptide B5 or one of the control: TCR-peptide B1, TCR-peptide derived from the Vβ17 chain, and an irrelevant peptide derived from hen egg lysozyme (HEL)11–25. Also, a group of mice treated with PBS were included as control. Mice were monitored for diabetes until 32 weeks of age.

In Fig. 4B, data pooled from two independent experiments are shown. At 32 weeks of age, only 7 of 29 (24%) of NOD mice vaccinated with TCR-peptide B5 developed diabetes, whereas 25 of 30 mice (83%) in the PBS-control group developed diabetes. In addition, 75% and 100% of mice primed with TCR-peptide B1 and HEL11–25 peptide, respectively, became diabetic by 32 weeks of age. Similarly, 62% of mice primed with the TCR Vβ17-derived peptide were diabetic at 16 weeks of age. Furthermore, histopathological analysis of pancreatic islets of mice treated with B5 peptide revealed that the incidence of both peri-insulitis (8.4%) and intra-insulitis (37.4%) was significantly lower than mice treated with B1 peptide (peri-insulitis, 24.4% and intra-insulitis, 69.1%) (data not shown). Collectively, these data demonstrate that female NOD mice nasally primed with the regulatory TCR-peptide B5 are significantly protected from T1D progression.

4. Discussion

In this study, using high-throughput sequencing, we analyzed the TCRβ repertoires from sorted memory CD4+ T cells collected from PaLN of prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice and compared them to that of islet-infiltrating memory CD4+ T cells (Marrero et al., 2013). The characterization of the TCR expressed by autoreactive memory T cells is important as it could be used to monitor the involvement of different clonotypes in T1D pathogenesis.

Both memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoires are highly diverse and predominantly composed of rare clonotypes that are present at low frequency in both prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice, consistent with the dominance of rare clonotypes within the memory TCRβ repertoire of healthy donors (Robins et al., 2009, Klarenbeek et al., 2010; Robins et al., 2012). Our data indicate that NOD mice select naturally a memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire that share similar features in both PaLN and in the pancreas, supporting the role of PaLN in priming of the autoimmune response. This may relate to the importance of PaLN in recruiting and activating islet-specific T cells in the NOD mice considering the drainage of β cell antigens into PaLN (Höglund et al., 1999; Sarukhan et al., 1999; Gagnerault et al., 2002; Graham et al., 2011, Calderon and Unanue, 2012). Consistently, significant perturbations of the TCR Vβ repertoire in PaLN of prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice suggested selection/expansion of diabetes-associated T cell responses in the PaLN (Marrero et al., 2012). Supporting this notion, expansion of antigen-specific Foxp3+ Tregs was recently reported to take place exclusively in PaLN of NOD mice after stimulation with microspheres coated with diabetes-specific antigens (Engman et al., 2015).

Furthermore, limited usage of TRBV genes in memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoires suggest a highly skewed repertoire in both PaLN and islets. This is consistent with a biased TRBV repertoire recently reported for islet-infiltrating T cells in 7-wk old NOD mice (Toivonen et al., 2015). Moreover, the usage of dominant TRBV genes such as TRBV13-2, TRBV13-1, TRBV5, TRBV1, TRBV2, and TRBV19 between prediabetic and diabetic mice was remarkably similar in both PaLN and islets, suggesting that the dominance of specific TRBV gene segments may be an important indicator of islet-specific autoimmune repertoires. These results suggest that the TCRβ repertoire of memory CD4+ T cells in PaLN share several characteristics with the islet-infiltrating repertoires. Currently, we are investigating whether these TCRβ chains are associated with diverse or oligoclonal TCR α-chains such as for the recognition of the insulin B:9–23 peptide (Simone et al., 1997, Nakayama and Eisenbarth, 2012).

Although the specificity of these clonotypes was not determined, it is noteworthy that some of the CDR3β sequences in PaLN in NOD mice have been previously shown to be associated with TCRs from islet antigen-reactive T cells, thereby, suggesting an antigen-driven islet autoimmunity. Most of these sequences identified rare clonotypes, consistent with a previous study showing low frequency of antigen-specific memory CD4 T cell clonotypes in peripheral blood of T1D patients (Estorninho et al., 2013). However, a recent study show the presence of a dominant clone in blood and islet repertoire of NOD mouse (Toivonen et al., 2015). Therefore, clone frequency may be an important indicator of immune response, consequently, the development of strategies for monitoring fluctuations of these clones in peripheral blood can be useful as an indicator of disease progression in at-risk or diabetic patients.

The diversity in the TCRs of PaLN-memory CD4+ T cells can be accounted by several mechanisms: (a) it can be an indication of the multiple-antigen reactivity in T1D where antigens spreading have been identified at different stages of disease in both human and NOD mice. Consistently, high TCR diversity is also found in antigen-specific responses in T1D as recently reported for GAD65-specific CD4+ T cells in the peripheral blood of pre-diabetic children and diabetic patients (Eugster et al., 2015); (b) it can be indicative of the regular influx of freshly recruited T cells between PaLN and pancreas that contain both antigen-specific CD4+ T cells and bystander CD4+ T cells (Calderon et al., 2011, Magnuson et al., 2015); and (c) Tregs recruited in response to the expansion of pathogenic effector T cells (Feuerer et al., 2009) are contributing to the diversity considering the heterogeneity and plasticity recently reported within the Foxp3+ Treg lineage (Sakaguchi et al., 2013).

A limited overlap of memory CD4+ clonotypes between PaLN and islets was found within individual NOD mice. However, clonotypes that were present at high frequency in islets of both prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice contribute significantly to the total memory TCRβ repertoire shared between PaLN and islets. These data suggest that even though dominant islet clonotypes are more probably found in PaLN, they exists at low frequency in the periphery. However, the variation in the number of sequences assembled from islets and PaLN may interfere with our ability to find more overlapping sequences in individual mice. The fact that both prediabetic and diabetic mice have overlapping clonotypes between PaLN and pancreas indicate that activated memory CD4+ T cells are continuously attracted to the islets, suggesting that they might play a dominant role in disease progression. Also, purified populations (sorted) of memory CD4+ T cells were analyzed, therefore, these memory CD4+ T cells might represent pathogenic clones against selected antigens that are continuously infiltrating the islets after priming in PaLN.

Furthermore, we found public TCRβ clonotypes in the PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire, which were shared between multiple prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice as reported before in islets (Marrero et al., 2013). Different indications suggest that some public TCRβ clonotypes might represent antigen-specific T-cell clones which are involved in the autoimmune pathogenesis of T1D: (a) public TCRβ clonotypes are memory CD4+ T cell clones that spontaneously were primed in the PaLN and pancreas of NOD mice during disease progression, (b) the TRBV gene segments dominantly used by public TCRβ clonotypes have been previously associated with either islet-reactivity or diabetes-related autoantigens (Drexler et al., 1993, Sarukhan et al., 1994, Simone et al., 1997, Baker et al., 2002, Wong et al., 2006, 2007; Li et al., 2009; Toivonen et al., 2015), and (c) several public clonotypes express CDR3β sequences matching other sequences reported in diabetogenic T cells or islets of NOD mice (Supplemental Table 1 and Table 2). These findings suggest that public memory CD4+ T cells may have advantage to drive or sustain anti-islet autoimmunity, perhaps by making preferential contact with islet-antigen/MHC in peripheral tissues. The utilization of specific TCRβ chains by the memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire in both islets and PaLN as well as by public clonotypes potentially can be used to identify autoimmune-prone memory CD4+ T cells involved in T1D.

The appearance of expanded peaks in the CDR3 spectratype of NOD mice compared to NOR mice support the notion that a disease-related response take place in PaLN of NOD mice. Whether public clonotypes or private clonotypes contribute to the perturbed spectratype profiles in the NOD mice is hard to differentiate. However, considering that (a) the TCRβ repertoire of memory CD4+ T cells in PaLN is dominated by rare clonotypes; (b) the repertoire is fundamentally private; (c) the majority of public clonotypes are among rare clonotypes, and (d) a limited number of TRBV genes are implicated in the T cell response within the PaLN of NOD mice, it is likely that significant expansions of specific peaks within particular Vβ families in the NOD may reflect the contribution of a large number of smaller responses. Remarkably, TRBV13-2 (Vβ8.2) gene, which is dominantly used by PaLN memory CD4+ T cells and particularly by public clonotypes, is the one that contain more peaks that are significantly larger in diabetes-susceptible NOD mice compared to diabetes-resistant NOR mice suggesting that diabetes-associated T cell responses may be involved in the perturbed profile.

Consistent with this idea, we show that targeting TCR-centered regulation against TCR Vβ8.2 (TRBV13-2) T cells significantly protects female NOD mice from progression toward T1D. While nasal priming with other TCR-derived peptides (B1 or Vβ17-derived peptide) or from the lysozyme is not protective. Previous studies showed that priming with TCR-peptide B5 reduce severity and incidence of murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) and collagen-induced arthritis. Priming with TCR-peptide B5 activates a naturally TCR-peptide-specific CD4+ Treg subset that in collaboration with a CD8+ Treg population specifically target Vβ8.2+ CD4+ effector T cells (Kumar et al., 1995; Kumar V et al., 1997; Madakamutil et al, 2003; Smith et al., 2010). This mechanism of antigen-specific regulation has been shown to be mediated by CD8αα+TCRαβ+ Tregs that recognize a different 9-mer peptide derived from the Vβ8.2 in the context of the class Ib MHC molecule Qa-1 (Smith and Kumar, 2008; Smith et al., 2009). These CD8αα+TCRαβ+ Tregs are able to induce apoptosis only in activated Vβ8.2+ CD4+ T cells but not in resting Vβ8.2+ or Vβ8.2- CD4+ T cells or in naïve T cells (Tang et al., 2006). Thus, we predict that nasal vaccination with TCR-peptide B5 in young NOD mice induces TCR-based regulatory CD4+ and CD8αα+TCRαβ+ T cells that target activated Vβ8.2+ CD4+ T cells and prevent T1D. It has been demonstrated that the TRBV13-2 gene segment (TCR Vβ8.2 chain) is preferentially utilized in several animal models of autoimmune diseases (Urban et al., 1988; Burns et al., 1989; Kumar et al., 1989; Osman et al., 1993; Rizzo et al., 1996) and the involvement of Vβ8.2+ T cells has been shown previously to be relevant to disease evolution in T1D. For example, Vβ8.2+ T cells are predominantly found in islets of very young prediabetic female NOD mice (Baker et al., 2002) and IGRP206–214-specific CD8+ T cells preferentially express TCR Vβ8.1/8.2 (Wong et al., 2006, 2007). Furthermore, depletion of Vβ8.2+ T cells prevented disease recurrence in pancreas isografts in diabetic NOD mice (Bacelj et al., 1990, 1992). Consistent with our data T-cell vaccination of NOD mice with either concanavalin A-activated lymphocytes or single chain TCRs specific for I-Ag7 RegII peptides or with the BDC2.5 single chain TCR significantly reduce incidence of diabetes in female NOD mice (Smerdon et al., 1993, Gurr et al., 2013). Collectively, these results are consistent with the involvement of Vβ8.2+ CD4+ T cells in progression of diabetes. Furthermore, these results support the notion that TCR-based regulation strategies targeting dominant TRBV genes in public memory T cells could be useful in the prevention of T1D.

5. Conclusion

In summary, the present studies substantially extend our previous study in islet-infiltrating memory CD4+ T cells to a detailed analysis of the TCRβ repertoire in PaLN-memory CD4+ T cells in NOD mice. We show that the TCRβ repertoire of PaLN-memory CD4+ T cells is highly restricted in TRBV genes usage, showing similarities with the memory repertoire in the pancreas (Marrero et al., 2013). In addition, public TCRβ clonotypes were also found in the PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire of both prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice. Public clonotypes with TCR CDR3β sequences matching those previously reported in diabetogenic T cells or associated with islet-antigen specific T cell responses were identified, suggesting that public clonotypes may play a relevant role in developing anti-islet autoimmunity. Importantly, targeting a dominant TRBV gene, TRBV13-2, which is utilized preferentially by memory clones using a TCR vaccination approach significantly protects female NOD mice from developing T1D. These data suggest that dominant TRBV genes used by public clonotypes can serve as surrogate markers for autoreactive T cells opening the possibility to investigate the role of public TCRβ memory clonotypes in human T1D.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Limited overlap of memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoires between PaLN and pancreas.

Public clonotypes are selected within the PaLN-memory CD4+ TCRβ repertoire.

Nasal treatment of female NOD mice with TCR-peptide B5 significantly prevents T1D.

Memory CD4+ T cells expressing TCR Vβ8.2 are involved in the progression of T1D.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship (3-2005-336 to I.M.), Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation grant (24-2007-362 to V.K.); American Diabetes Association Junior Faculty Award (1-11-JF-29 to I.M.), and National Institutes of Health grants (R01 CA100660 and R01 AA020864 to V.K.).We thank Dr. Randle Ware (La Jolla, CA) for a critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- T1D

type I diabetes

- PaLN

pancreatic lymph nodes

- NOD

non-obese diabetic mice

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arstila TP, Casrouge A, Baron V, Even J, Kanellopoulos J, Kourilsky P. A direct estimate of the human alphabeta T cell receptor diversity. Science. 1999;286:958–961. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelsson S, Chéramy M, Hjorth M, Pihl M, Akerman L, Martinuzzi E, Mallone R, Ludvigsson J, Casas R. Long-lasting immune responses 4 years after GAD-alum treatment in children with type 1 diabetes. PLoS. One. 2011;6:e29008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacelj A, Charlton B, Koulmanda M, Mandel TE. The role of V beta 8 cells in disease recurrence in isografts in diabetic NOD mice. Transplant. Proc. 1990;22:2167–2168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacelj A, Mandel TE, Charlton B. Anti-V beta 8 antibody therapy prevents disease recurrence in fetal pancreas isografts in spontaneously diabetic nonobese diabetic mice. Transplant. Proc. 1992;24:220–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker FJ, Lee M, Chien YH, Davis MM. Restricted islet-cell reactive T cell repertoire of early pancreatic islet infiltrates in NOD mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:9374–9379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142284899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berschick P, Fehsel K, Weltzien HU, Kolb H. Molecular analysis of the T-cell receptor Vβ5 and Vβ8 repertoire in pancreatic lesions of autoimmune diabetic NOD mice. J. Autoimm. 1993;6:405–422. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1993.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns FR, Li XB, Shen N, Offner H, Chou YK, Vandenbark AA, Heber-Katz E. Both rat and mouse T cell receptors specific for the encephalitogenic determinant of myelin basic protein use similar V alpha and V beta chain genes even though the major histocompatibility complex and encephalitogenic determinants being recognized are different. J. Exp. Med. 1989;169:27–39. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon B, Carrero JA, Miller MJ, Unanue ER. Entry of diabetogenic T cells into islets induces changes that lead to amplification of the cellular response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:1567–1572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018975108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon B, Unanue ER. Antigen presentation events in autoimmune diabetes. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2012;24:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candéias S, Katz J, Benoist C, Mathis D, Haskins K. Islet-specific T-cell clones from nonobese diabetic mice express heterogeneous T-cell receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:6167–6170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delovitch TL, Singh B. The nonobese diabetic mouse as a model of autoimmune diabetes: immune dysregulation gets the NOD. Immunity. 1997;7:727–738. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diz R, Garland A, Vincent BG, Johnson MC, Spidale N, Wang B, Tisch R. Autoreactive effector/memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells infiltrating grafted and endogenous islets in diabetic NOD mice exhibit similar T cell receptor usage. PLoS. One. 2012;7:e52054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drexler K, Burtles S, Hurtenbach U. Limited heterogeneity of T-cell receptor Vβ gene expression in the early stage of insulitis in NOD mice. Immunol. Lett. 1993;37:187–196. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(93)90030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engman C, Wen Y, Meng WS, Bottino R, Trucco M, Giannoukakis N. Generation of antigen-specific Foxp3+ regulatory T-cells in vivo following administration of diabetes-reversing tolerogenic microspheres does not require provision of antigen in the formulation. Clin. Immunol. 2015;160:103–123. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estorninho M, Gibson VB, Kronenberg-Versteeg D, Liu YF, Ni C, Cerosaletti K, Peakman M. A novel approach to tracking antigen-experienced CD4 T cells into functional compartments via tandem deep and shallow TCR clonotyping. J. Immunol. 2013;191:5430–5440. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugster A, Lindner A, Catani M, Heninger AK, Dahl A, Klemroth S, Kühn D, Dietz S, Bickle M, Ziegler AG, Bonifacio E. High diversity in the TCR repertoire of GAD65 autoantigen-specific human CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2015;194:2531–2538. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuerer M, Shen Y, Littman DR, Benoist C, Mathis D. How punctual ablation of regulatory T cells unleashes an autoimmune lesion within the pancreatic islets. Immunity. 2009;31:654–664. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JD, Warren RL, Webb JR, Nelson BH, Holt RA. Profiling the T-cell receptor beta-chain repertoire by massive parallel sequencing. Genome. Res. 2009;19:1817–1824. doi: 10.1101/gr.092924.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnerault MC, Luan JJ, Lotton C, Lepault F. Pancreatic lymph nodes are required for priming of beta cell reactive T cells in NOD mice. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:369–377. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galley KA, Danska JS. Peri-islet infiltrates of young non-obese diabetic mice display restricted TCR β-chain diversity. J. Immunol. 1995;154:2969–2982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham KL, Krishnamurthy B, Fynch S, Mollah ZU, Slattery R, Santamaria P, Kay TW, Thomas HE. Autoreactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes acquire higher expression of cytotoxic effector markers in the islets of NOD mice after priming in pancreatic lymph nodes. Am. J. Pathol. 2011;178:2716–2725. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurr W, Shaw M, Herzog RI, Li Y, Sherwin R. Vaccination with single chain antigen receptors for islet-derived peptides presented on I-A(g7) delays diabetes in NOD mice by inducing anergy in self-reactiveT-cells. PLoS. One. 2013;8:e69464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höglund P, Mintern J, Waltzinger C, Heath W, Benoist C, Mathis D. Initiation of autoimmune diabetes by developmentally regulated presentation of islet cell antigens in the pancreatic lymph nodes. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:331–339. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klarenbeek PL, Tak PP, van Schaik BD, Zwinderman AH, Jakobs ME, Zhang Z, van Kampen AH, van Lier RA, Baas F, de Vries N. Human T-cell memory consists mainly of unexpanded clones. Immunol. Lett. 2010;133:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Kono DH, Urban JL, Hood L. The T-cell receptor repertoire and autoimmune diseases. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1989;7:657–682. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.003301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Sercarz EE. The involvement of T cell receptor peptide-specific regulatory CD4+ T cells in recovery from antigen-induced autoimmune disease. J. Exp. Med. 1993;178:909–916. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.3.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Tabibiazar R, Geysen HM, Sercarz E. Immunodominant framework region 3 peptide from TCR V beta 8.2 chain controls murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 1995;154:1941–1950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Aziz F, Sercarz E, Miller A. Regulatory T cells specific for the same framework 3 region of the Vbeta8.2 chain are involved in the control of collagen II-induced arthritis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Exp. Med. 1997;185:1725–1733. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.10.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Sercarz E. An integrative model of regulation centered on recognition of TCR peptide/MHC complexes. Immunol. Rev. 2001;182:113–121. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1820109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin E, Burke G, Pugliese A, Falk B, Nepom G. Recurrence of autoreactive antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in autoimmune diabetes after pancreas transplantation. Clin. Immunol. 2008;128:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.03.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Wang B, Frelinger JA, Tisch R. T-cell promiscuity in autoimmune diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57:2099–2106. doi: 10.2337/db08-0383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, He Q, Garland A, Yi Z, Aybar LT, Kepler TB, Frelinger JA, Wang B, Tisch R. beta cell-specific CD4+ T cell clonotypes in peripheral blood and the pancreatic islets are distinct. J. Immunol. 2009;183:7585–7591. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madakamutil LT, Maricic I, Sercarz E, Kumar V. Regulatory T cells control autoimmunity in vivo by inducing apoptotic depletion of activated pathogenic lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 2003;170:2985–2992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson AM, Thurber GM, Kohler RH, Weissleder R, Mathis D, Benoist C. Population dynamics of islet-infiltrating cells in autoimmune diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015;112:1511–1516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423769112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrero I, Vong A, Dai Y, Davies JD. T cell populations in the pancreatic lymph node naturally and consistently expand and contract in NOD mice as disease progresses. Mol. Immunol. 2012;52:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrero I, Hamm DE, Davies JD. High-Throughput sequencing of islet-infiltrating memory CD4+ T cells reveals a similar pattern of TCR Vβ usage in prediabetic and diabetic NOD mice. PLoS. One. 2013;8:e76546. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti P, Scirpoli M, Rigamonti A, Mayr A, Jaeger A, Bonfanti R, Chiumello G, Ziegler AG, Bonifacio E. Evidence for in vivo primed and expanded autoreactive T cells as a specific feature of patients with type 1 diabetes. J. Immunol. 2007;179:5785–5792. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.5785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata M, Yoon JW. Studies on autoimmunity for T-cell-mediated beta-cell destruction. Distinct difference in beta-cell destruction between CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell clones derived from lymphocytes infiltrating the islets of NOD mice. Diabetes. 1992;41:998–1008. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.8.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano N, Kikutani H, Nishimoto H, Kishimoto T. T cell receptor V gene usage of islet β cell-reactive T cells is not restricted in non-obese diabetic mice. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:1091–1097. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.5.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama M, Eisenbarth GS. Paradigm shift or shifting paradigm for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2012;61:976–978. doi: 10.2337/db12-0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolich-Zugich J, Slifka MK, Messaoudi I. The many important facets of T-cell repertoire diversity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:123–132. doi: 10.1038/nri1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öling V, Reijonen H, Simell O, Knip M, Ilonen J. Autoantigen-specific memory CD4+ T cells are prevalent early in progression to Type 1 diabetes. Cell. Immunol. 2012;273:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]