Abstract

Available drugs are unable to effectively rescue the folding defects in vitro and ameliorate the clinical-phenotype of cystic fibrosis (CF), caused by deletion of F508 (ΔF508 or F508del) and some point mutations in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a plasma membrane (PM) anion channel. To overcome the corrector efficacy ceiling, here we show that compounds targeting distinct structural defects of CFTR can synergistically rescue mutants expression and function at the PM. High throughput cell-based screens and mechanistic analysis identified three small-molecule series that target defects at the nucleotide binding domain (NBD1), NBD2 and their membrane spanning domains (MSDs) interfaces. While individually these compounds marginally improve ΔF508-CFTR folding efficiency, function, and stability, their combinations lead to ~50–100% of wild type-level correction in immortalized and primary human airway epithelia, and in mouse nasal epithelia. Likewise, corrector combinations were effective for rare missense mutations in various CFTR domains, probably acting via structural allostery, suggesting a mechanistic framework for their broad application.

More than 2000 mutations in the cystic fibrosis (CF) gene, encoding the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR or ABCC7), have been identified (Cystic Fibrosis Mutation Database: http://www.genet.sickkids.on.ca/app). Most of these mutations manifest in loss-of-function of the CFTR anion channel activity by complex cellular mechanisms1, accounting for the CF clinical phenotype2. CF morbidity and mortality are primarily caused by the associated lung disease, a consequence of mucus dehydration, reduced mucociliary clearance, recurrent infection and hyperinflammation of the airways3.

CFTR, a member of the ATP-binding cassette transporter superfamily, comprises two membrane spanning domains (MSD1 and MSD2), two nucleotide binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2) and a unique regulatory (R) domain4, which allosterically communicate at the functional and biochemical level5–7. The most common mutation, deletion of phenylalanine 508 (ΔF508 or F508del) in NBD1, similar to numerous other missense mutations, impairs CFTR domain folding, rendering the channel susceptible to premature degradation within the ER, as well as the ER-escaped pool by the plasma membrane (PM) protein quality control mechanism1,8. Targeted introduction of second site suppressor mutations revealed that robust folding correction of ΔF508-CFTR requires stabilization of NBD1 and its interfaces with MSD2, established primary conformational defects of the ΔF508 mutant9–11 or hyperstabilization of the ΔF508-NBD112. The structural challenges imposed by the mutant NBD1 to isolate hypestabilizing small molecule for monotherapy13 prompted us to resort to rationally designed combinatorial corrector therapy. This approach was also favored by the cooperative nature of domain folding of wild-type CFTR (WT-CFTR) and cooperative misfolding of CF mutations (including ΔF508), distributed throughout the channel, manifesting in the propagation of localized misfolding to multiple domains14–16. As a consequence, we assumed that improving NBD1 folding and any permutation of domain-domain interactions should facilitate the conformational rescue of ΔF508-CFTR16,17. This paradigm would entail that combination of correctors targeting both primary9,10 and secondary structural defects (e.g NBD2 misfolding or its domain interactions18) may more effectively restore biosynthetic processing of ΔF508-CFTR, as well as other processing mutants than monotherapy17.

Mechanistically, type I correctors support the formation of NBD1-MSD1 and NBD1-MSD2 interfaces, type II target NBD2 and/or its interfaces, and type III facilitate NBD1 folding and/or impede its unfolding17. We and others have shown that the combination of type I and type II correctors leads to modest correction of ΔF508-CFTR misfolding17,19–21. Due to the lack of available potent and effective type III correctors, chemical chaperones were used as surrogates in our proof of principle studies17. However, clinical utility of chemical chaperones is very limited due to their lack of specificity and modest potency/efficacy.

VX-809 (lumacaftor), represented until recently22 the sole approved corrector23 with a type I mechanism17,24. VX-809 in combination with the gating potentiator VX-770 (ivacaftor) provides modest clinical benefit to 50% of CF patients carrying two copies of the ΔF508 mutation25. The limited efficacy of the VX-809/VX-770 combination (Orkambi) therapy may be attributed to the lack of ΔF508-NBD1 stabilization, and the likely attenuated biogenesis of ΔF508-CFTR upon chronic VX-770 treatment26,27. Thus, there is an unmet need to identify more efficacious correctors of ΔF508-CFTR folding defects that will translate into improved clinical benefit in CF patients.

Here we report the isolation and characterization of novel type I, II and III corrector compounds that individually exhibit limited rescue of ΔF508-CFTR, but in combination robustly restore the mutant biochemical and functional expression in airway cells. This triple corrector combination (3C) has profound rescue efficacy in primary human bronchial (HBE) and nasal epithelia (HNE) of ΔF508 homozygous patients and is also effective in a ΔF508 CF mouse model. Importantly, the 3C combination also rescued several CFTR2 (CFTR2 project: http://cftr2.org)2 processing mutants with poor susceptibility to VX-809. The in vitro and in vivo results confirm the feasibility of the proposed framework for allosteric folding correction of various CFTR mutants and the efficacy of structure-guided selection strategy for corrector combinations.

Results

Identification of ΔF508-CFTR corrector hits with different scaffolds

To isolate corrector molecules targeting distinct structural defects of ΔF508-CFTR with limited efficacy, we selected our recently developed biochemical screening assay19,26, which displays enhanced PM detection sensitivity of CFTR relative to that of the halide-sensitive functional measurements (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1a-c). To this end, ΔF508-CFTR, containing a horseradish peroxidase isoenzyme C (HRP-C) in its fourth extracellular loop, was expressed in CFB41o- cells, an established human bronchial epithelial model with CFTRΔF508/ΔF508 genetic background but no detectable protein expression28.

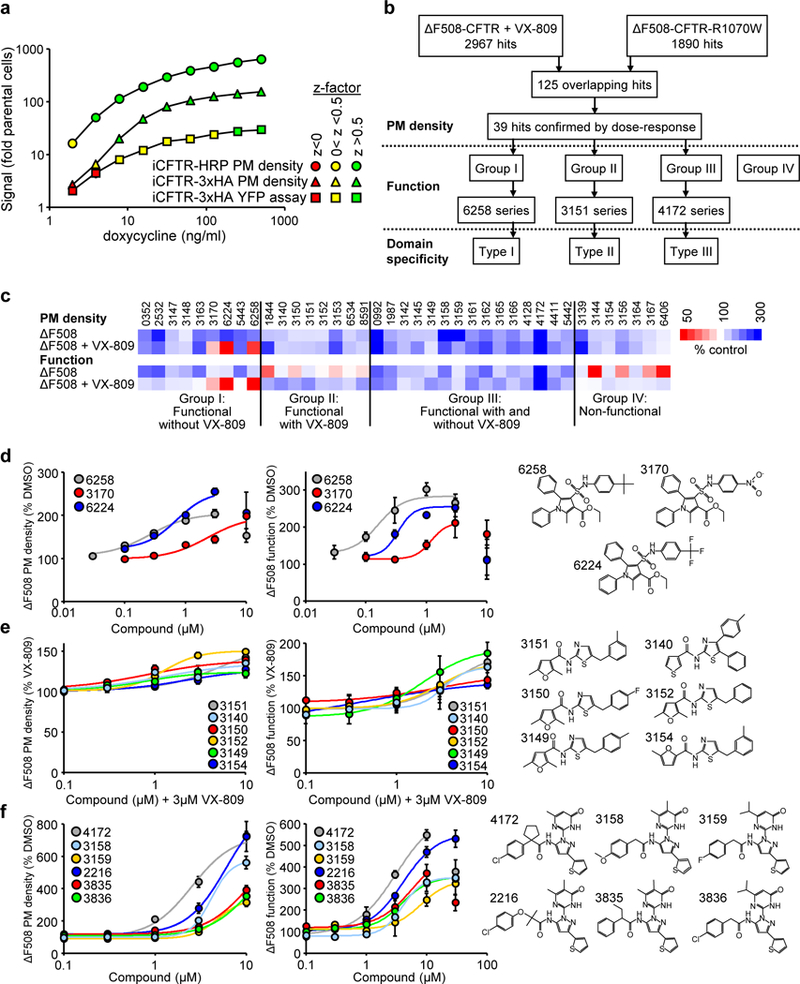

Figure 1.

Identification of small-molecule ΔF508-CFTR correctors by high-throughput screening. (a) Comparison of the sensitivity and robustness of the plasma membrane (PM) density or functional HTS assays of HRP- or 3HA-tagged CFTR (n = 3). WT-CFTR expression in CFBE41o- was induced by increasing doxycycline concentrations. CFTR PM density and function were determined as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a-c. Results are depicted as fold change to parental cell background. The z-factor ranges are color coded. (b) Flow chart of the screening and corrector mechanism identification process. (c) Heat map of corrector effect (10 μM, 24 hours, 37°C) on the PM density and function of ΔF508-CFTR in CFBE41o- alone or in combination with 3 μM VX-809. The underlying data are depicted as dose-response curves or bar plots in Supplementary Fig. 1d-h (n = 2–57). (d-f) PM density and function dose-response (left and middle) and structures (right) of the 6258 corrector series (d), 3151 corrector series (e), and 4172 corrector series (f). The ΔF508-CFTR PM density and function were determined by PM-ELISA and YFP quenching assay, respectively (n = 3). Data in a and d-f are means ± SEM of the indicated number of independent experiments.

PM expression of the mutant was detected by luminometry in the presence of the cell-impermeant substrate19,26 in 1536 well plates. We screened ~600,000 drug-like compounds in the ~250–550 Dalton molecular weight range from the Novartis academic collection screen (ACS) library with robust signal-to-background ratios and Z’ factors (Fig. 1b). Two primary screens were performed to preferentially select type II and type III corrector hits, , one in the presence of VX-809 and another using a ΔF508-CFTR variant that contained the interface-stabilizing mutation R1070W9,17,29. These screens yielded 2967 and 1890 primary hits, respectively, of which 125 compounds were identified in both screens based on the increase in luminescence signal by >3 standard deviation (SD) relative to DMSO or VX-809 treated controls (Fig. 1b). Dose-response measurements in presence and absence of VX-809 confirmed 39 active compounds (Fig. 1c-f and Supplementary Fig. 1d,e and Supplementary Table 1).

To determine whether PM accumulation of ΔF508-CFTR was correlated with its functional gain, the PM anion conductance was determined by the halide-sensitive YFP quenching assay (Supplementary Fig. 1b)26 after PKA-activation and potentiation of the channel with forskolin/IBMX/cpt-cAMP and genistein, respectively. Based on the interaction/interdependence of hits with VX-809 and the relation between ΔF508-CFTR functional gain and PM density, we categorized the hits into four groups: group I promoted ΔF508-CFTR conductance only in absence of VX-809, group II increased the channel function in combination with VX-809, group III increased ΔF508-CFTR function regardless of the VX-809 presence, and group IV increased ΔF508-CFTR function by less than 20% (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1f-h).

Within these groups we next identified clusters of compounds sharing a common scaffold: group I contained the 6258 series of sulfamoyl-pyrrol compounds (6258, 3170, 6224) (Fig. 1d), group II contained the 3151 series of aminothiazole compounds (3151, 3140, 3150, 3152 supplemented by 3149 and 3154 from group III and group IV, respectively) (Fig. 1e), and group III contained the 4172 series of pyrazole compounds (4172, 3158, 3159, supplemented by 2216, 3835 and 3836 from limited SAR screen) (Fig. 1f). The EC50 of ΔF508-CFTR functional correction in CFBE41o- for the representative 6258, 3151 and 4172 compounds was 0.16, 4.2 and 3.1 μM, respectively (Fig. 1d-f and Supplementary Table 1).

Clustering corrector hits based on mechanism of action

First, we tested whether any of the best representative correctors could directly bind to isolated ΔF508-NBD1 by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) as described13. The 4172 compound, but not 3151 or 6258, showed dose-dependent binding with a KD = 38 μM to the in vivo biotinylated ΔF508-NBD1, containing the single stabilizing mutation F494N (Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Table 2), necessary prerequisite for a type III mechanism of corrector action. We also confirmed that bromoindole-3-acetic acid (BIA), the first identified type III corrector12, has >25-fold lower affinity (KD >1000 μM)13 than 4172 (Supplementary Fig. 2c,d and Supplementary Table 2).

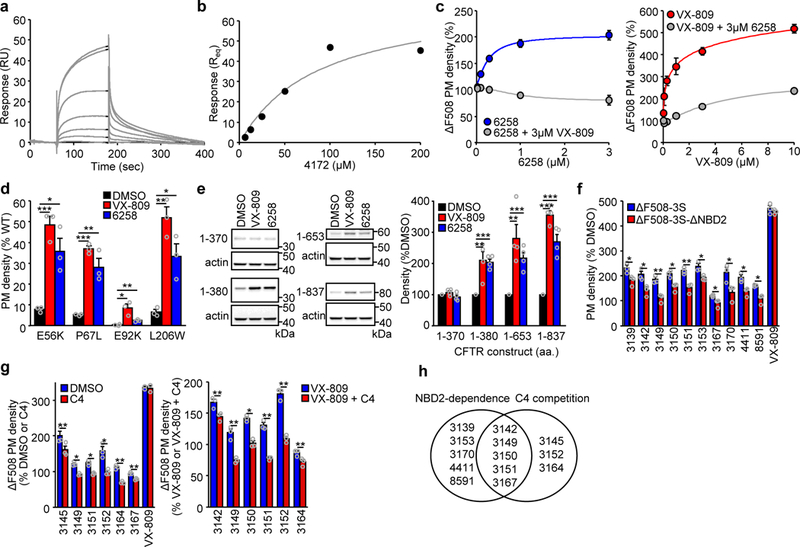

Figure 2.

Corrector mechanism of action. (a,b) Representative surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensorgram (a) and binding isotherm (b) for the association of 4172 (0–200 μM) to immobilized ΔF508-NBD1–1S. (c) Competing effect of VX-809 (3 μM) on the 6258 dose-dependent elevation of the ΔF508-CFTR PM density (left panel, n = 3). Inhibition of the VX-809 dose-dependent ΔF508-CFTR PM correction in presence of 3 μM 6258 (right panel, n = 3). (d) PM density correction of the N-terminal tail (E56K, P67L) and MSD1 (E92K, L206W) CFTR folding mutants by VX-809 or 6258 (3 μM, 24 hours) in CFBE41o- (n = 3). (e) Representative immunoblot (left panel) and quantification of the expression level by densitometry (right panel) of indicated N-terminal CFTR fragments expressed in HEK293 cells with or without VX-809 or 6258 (3 μM, 24 hours) treatment. The fragments 1–653 and 1–837 contained the ΔF508 mutation. All fragments were detected with anti-CFTR antibody MM13–4 (n = 4). Uncropped immunoblots are presented in Supplementary Figure 11. (f) The effect of indicated correctors (10 μM, 24 hours) on the PM density of ΔF508-CFTR-3S (containing the solubilizing mutations F494N, Q637R, F492S) or ΔF508-CFTR-3S lacking the NBD2 domain (ΔNBD2) in CFBE41o- relative to untreated cells (n = 3). (g) Relative effect of C4 competition (10 μM, 24 hours) on the PM density of ΔF508-CFTR in CFBE41o- treated with the indicated correctors (10 μM) alone (left panel, n = 3) or in combination with 3 μM VX-809 (right panel, n = 3). (h) Venn-diagram clustering of compounds that rescue effect required NBD2 and/or was attenuated by C4. Data in c-g are means ± SEM of the indicated number of independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. The precise P-values are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Compound 6258 was able to promote ΔF508-CFTR PM accumulation only in the absence of VX-809. This was confirmed by dose-dependent inhibitory effect of VX-809 (Fig. 2c). Vice versa, exposure of ΔF508-CFTR to 6258 reduced the VX-809-induced PM expression in CFBE41o- (Fig. 2c). Similarly to VX-809 (ref. 24), we documented that 6258 exposure corrected the PM density of several processing mutations in the MSD1 (E56K-, P67L- and L206W-CFTR to > 25% of WT, as well as, E92K-CFTR to a lower extent) expressed in CFBE41o- (Fig. 2d). VX-809 can stabilize the N-terminal fragments of WT-CFTR, encompassing amino acid (aa) 1–380 (refs. 17,24) that may resemble the mutant folding intermediates. Likewise, 6258 treatment induced the accumulation of N-terminal CFTR fragments: aa 1–380 (MSD1), aa 1–653 (MSD1-ΔF-NBD1) and aa 1–837 (MSD1- ΔF-NBD1-R), but not aa 1–370 in CFBE41o- (Fig. 2e). Jointly, these results suggest that despite the divergent chemical structure, 6258 exhibits a type I mechanism of action and may have an overlapping binding site with VX-809.

The aminothiazol compound 3151 has structural similarity to the investigational type II correctors C4 and D-01 that require NBD2 for corrector action17,19,30. The folding efficacy of a subset of the initial 39 compounds, but not of VX-809, was reduced or prevented upon deletion of the NBD2 domain in a ΔF508-CFTR variant containing three solubilising mutations (F494N, Q637R and F429S31; ΔF508–3S-1218X-CFTR) that partially restore NBD1 folding, but not the NBD1-MSD2 interface defect (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 2e). Concordantly, the presence of C4 alone or with VX-809 reduced the corrector efficacy of these compounds, suggesting an overlapping mechanism of action (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 2f,g). We infer that members of the 3151 series likely conform to a type II mechanism, since their efficacy was compromised by NBD2 deletion and C4 competition (Fig. 2h).

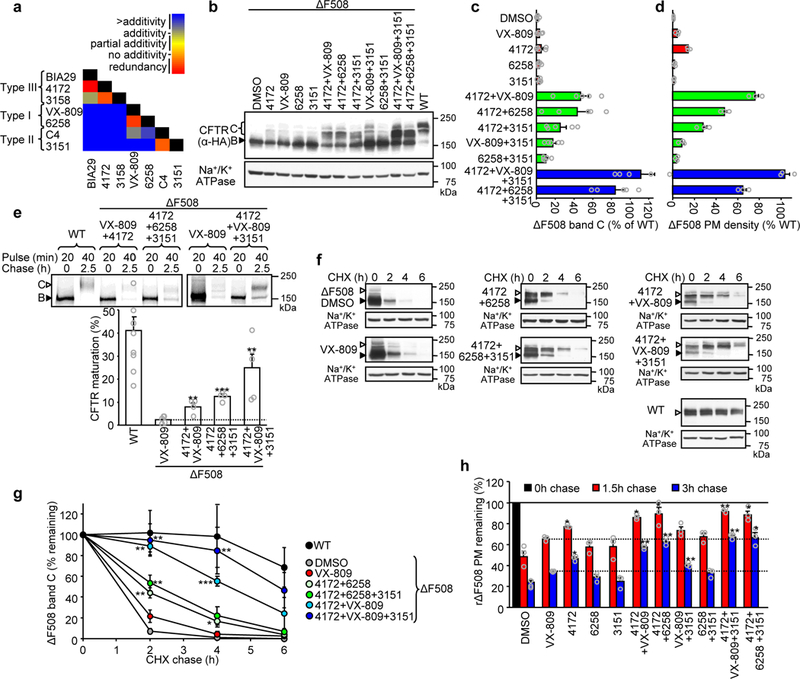

Cooperative rescue of biogenesis, PM expression and stability by corrector combinations

We used combinatorial profiling of correctors with distinct mechanism of actions to optimize for additive/synergistic rescue of ΔF508-CFTR PM density and function. First, we tested pair-wise combinations of type I (6258 and VX-809), II (C4 and 3151), III [2-(5-bromo-1H-indol-1-yl)acetic acid (BIA29, a structural analog of BIA)] and putative type III (4172, 3158) correctors by comparing their efficacy with that of calculated additivity of individual compounds (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 3a,b). As expected, combinations of mechanistically similar correctors (e.g. BIA29 and 4172, 4172 and 3158, VX-809 and 6258, as well as C4 and 3151) failed to exert additive rescue or showed negative cooperativity, whereas combinations of different types elicited more than additive folding rescue (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 3b). This paradigm became more apparent when, after normalizing for the mRNA level (Supplementary Fig. 3c), ΔF508-CFTR PM density and the abundance of the mature, complex-glycosylated form (band C) was expressed as percentage of WT-CFTR (Fig. 3b-d). Combination of the putative type III (4172) and type I (VX-809) correctors increased the ΔF508-CFTR PM density and band C to 76% and 47% of WT, respectively, in CFBE41o- (Fig. 3b-d). Remarkably, 3C of 3151 (type II) with 4172 and VX-809 restored PM density and band C expression of ΔF508-CFTR to the WT level, translating into >10 fold higher corrector efficacy than VX-809 treatment alone (Fig. 3b-d). Replacing VX-809 with type I corrector 6258 in the combination, also elevated PM density and band C accumulation of ΔF508-CFTR, to 65% and 85% of WT, respectively (Fig. 3b-d).

Figure 3.

Structure-guided combination of corrector compounds restores ΔF508-CFTR biogenesis and stability. (a) Combinatorial profiling of compound pair effect on ΔF508-CFTR PM density in comparison to their theoretical additivity (n = 3). The primary PM density data are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3b. (b-d). Effect of indicated single correctors or corrector combinations (4172, 3151– 10 μM; VX-809, 6258 – 3 μM, 24 hours, 37°C) on the expression pattern of ΔF508-CFTR in CFBE41o- determined by quantitative immunoblotting (b) and densitometry (c, n = 5) or measured by PM ELISA (d, n = 3). ΔF508-CFTR values were normalized with CFTR mRNA abundance (Supplementary Fig. 3c) and are expressed as percentage of WT-CFTR control. (e) Determination of ER folding efficiency of WT-CFTR (n = 9) or ΔF508-CFTR in the presence of VX-809 (3 μM, 24 hours, n = 5) or indicated corrector combinations (n = 5 for 4172+VX-809+3151; n = 4 for 4172+VX-809 and 4172+6258+3151) by metabolic pulse chase technique and phosphoimage analysis. The folding efficiency was calculated as the percentage of pulse-labeled, immature core-glycosylated CFTR (B-band, filled arrowhead) conversion into the complex-glycosylated form (C-band, open arrowhead). (f-g) Stability of WT-CFTR or ΔF508-CFTR in CFBE41o- cells upon treatment with VX-809 or compound combinations was determined by quantitative immunoblotting with CHX chase (representative immunoblots of n = 3 independent experiments). The remaining complex-glycosylated (open arrowhead) form was quantified by densitometry and is expressed as percent of the initial amount (panel g, n = 3). (h) The effect of individual compounds or their combinations on the PM stability of low-temperature rescued (48 hours, 26°C) ΔF508-CFTR after 1.5 and 3 hour chase at 37°C (n = 3). Data in c-e and g-h are means ± SEM of the indicated number of independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test in comparison to VX-809 treated samples. The precise P-values are listed in Supplementary Table 4. The uncropped versions of the immunoblots in b and f and of the autoradiographs in e are shown in Supplementary Figure 11.

To test the specificity of the novel correctors, we determined their effect on the PM density of other native or conformationally defective membrane proteins. Combinations of 4172, 6258 and 3151 alone or with VX-809, did not substantially affect the PM expression of the transferrin receptor (TfR), or the chimeric proteins HRP-CD4TM, and HRP-CD4TM-λWT, as well as the mutant form HRP-CD4TM-λL57C representing native and misfolded endosomal or PM targeted transmembrane model proteins32 (Supplementary Fig. 3d-f). Likewise, single correctors or 3C negligibly altered the PM density of mutants of polytopic transmembrane proteins, associated with inherited conformational diseases; megalencephalic leukoencephalopathy with subcortical cyst 1 (MLC1-P92S and MLC1-S280L)33, diabetes insipidus (vasopressin 2 receptor; V2R-Y128S)32,34 and Long QT2 syndrome (human Ether-à-go-go-Related Gene; hERG-G601S)35 (Supplementary Fig. 3g-h).

The ΔF508 mutation diminishes the conformational maturation efficiency of CFTR at the ER from ~40% to <1% and accelerates the channel turnover in post-ER compartments1,16. To test whether corrector combinations can rectify these defects, first the folding efficiency of the ΔF508-CFTR nascent chains was measured by metabolic pulse-chase technique. The conversion of the pulse-labeled core-glycosylated channel into complex-glycosylated form indicated that the maturation efficiency of WT-CFTR14,16 was reduced from ~41% to ~2.3% by the ΔF508 mutation in the presence of VX-809 (ref. 26) (Fig. 3e). Corrector combinations 4172+VX-809, 4172+6258+3151 or 4172+VX-809+3151, however, enhanced the ER folding efficiency of the mutant to 8%, 13%, and 25%, respectively (Fig. 3e). Thus, the mutant maximum folding efficiency reached ~60% of the WT in the presence of 3C, representing >10-fold increase of the VX-809 effect.

Corrector combinations also led to stabilization of the mature, complex-glycosylated ΔF508-CFTR, measured by immunoblotting and cycloheximide (CHX)-chase (Fig. 3f,g). The 3C rendered WT-like cellular stability to the mutant (Fig. 3f,g). Similar results were obtained for ΔF508-CFTR stability at the PM (Fig. 3h), indicating that the stability of both the PM and post-ER pools of rescued ΔF508-CFTR approach that of the WT. Thus, the combination of different types of correctors profoundly increases both the biogenesis efficacy and post-ER stability of mature ΔF508-CFTR, likely by shifting its final fold to near-native conformation.

To support this inference, the protease resistance of the complex-glycosylated mutant was determined in microsomes, isolated from cells exposed to 3C for 24 hours, by limited trypsinolysis and immunoblotting with domain specific antibodies. The protease sensitivity of the full-length ΔF508-CFTR (Fig. 4a), as well as its domains (NBD2, MSD1 and MSD2) (Supplementary Fig. 4) was dramatically higher than that of the WT, confirming the mutant global misfolding15,16,36. Treatment with 3C profoundly increased the protease resistance of the mature ΔF508-CFTR and its individual domains close to its WT counterpart, suggesting that domain folding was allosterically propagated and effectively led to global conformational correction (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 4).

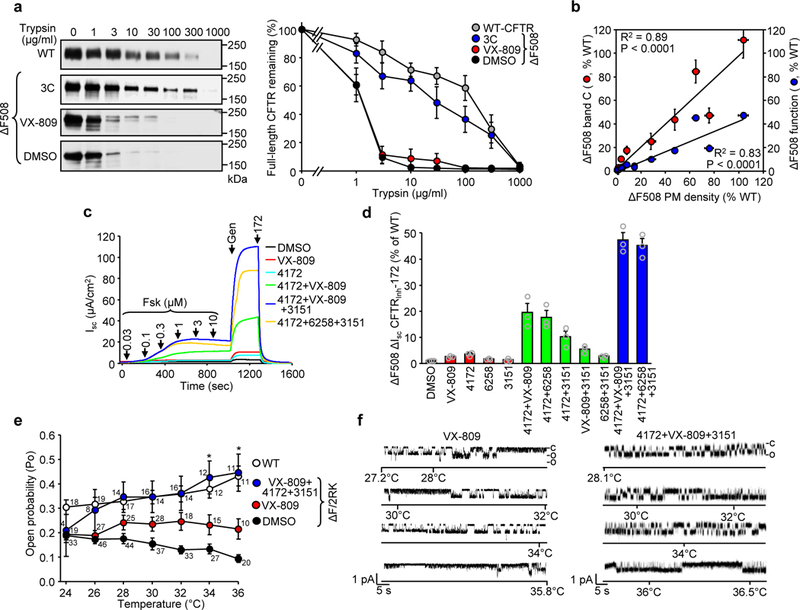

Figure 4.

Corrector combinations rescue the ΔF508-CFTR folding and functional defects. (a) The WT- or ΔF508-CFTR conformation in isolated microsomes was probed by limited trypsinolysis and immunoblotting (left panel). Microsomes isolated from BHK-21 cells, treated with DMSO, VX-809 or 4172+VX-809+3151 corrector combination (3C), were exposed to increasing concentrations of trypsin and the remaining full-length CFTR was quantified by immunoblotting. Complex-glycosylated WT- or ΔF508-CFTR was expressed as the percentage of the initial amount (right panel, n = 4). (b) Correlation between the PM density (n = 3) and band C abundance (n = 5) or activation (Fsk + Gen, n = 3) of ΔF508-CFTR after treatment with single correctors or corrector combinations as determined in Fig. 3c,d and panel (d), respectively. The Pearson correlation coefficient and the associated P-value are shown. (c,d) Effect of indicated single correctors or corrector combinations on the short-circuit current (Isc) of ΔF508-CFTR in CFBE41o-. Representative traces are shown in c. ΔF508-CFTR function (n = 3) normalized with CFTR RNA abundance (Supplementary Fig. 3c) is expressed as percentage of WT function in d. (e,f) The effect of VX-809 or 3C on thermal inactivation of ΔF508-CFTR-2RK reconstituted into an artificial phospholipid bilayer. The Po of protein kinase A–activated CFTRs was analyzed at the indicated temperatures (e), WT (total recording time for each point 16–23 min, n = 11–19, exact number of independent records for each temperature is indicated in the graph), ΔF508–2RK (38–48 min, n = 20–46), ΔF508–2RK + VX809 (6–27 min, n = 10–26), and ΔF508–2RK + 3C (4–18 min, n = 4–16). Significance between the VX-809 and 3C treated channel Po was calculated by two-sided Mann-Whitney U test. *P = 0.04 at 34°C and 0.03 at 36°C. The Po values of untreated ΔF508-CFTR-2RK and WT-CFTR are shown for comparison38. Representative channel activities for ΔF508-CFTR-2RK after VX-809 (two channels) or 3C (single channel) treatment during the temperature ramp are shown in f. The channel open (o) and closed (c) states are indicated. Data in a-b, d and e are means ± SEM of the indicated number of independent experiments.

Functional rescue of ΔF508-CFTR by corrector combinations

Corrector induced PM and band C accumulation of the ΔF508-CFTR correlated well with its functional recovery, measured by short-circuit current (Isc), stimulated by forskolin and acute potentiation (Fig. 4b). However, the functional gain was ~50% less than expected based on the PM density measurements. Isc was 19% and 47% of the WT after exposing the cells to 4172+VX-809 and 3C correctors, respectively (Fig. 4c,d and Supplementary Fig. 5a). Addition of 3C during Isc measurement caused a small (~12%) but significant decrease in the maximal Isc of 3C corrected ΔF508-CFTR (Supplementary Fig. 5b), an observation that led us to explore whether individual correctors can exhibit some inhibitory effect. Acute addition of 4172 and 3151 decreased the forskolin-stimulated Isc of low-temperature rescued ΔF508-CFTR, both with and without potentiation (Supplementary Fig. 5c,d) and of WT-CFTR (Supplementary Fig. 5e). The inhibitory effect of 4172 and 3151 on ΔF508-CFTR was ~15% and ~25%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5f), at least partly explaining the attenuated functional correction efficacy.

The effect of corrector combination on single molecule ΔF508-CFTR, containing the R29K and R555K (2RK) mutations, was measured after reconstitution of the temperature rescued channel into planar phospholipid bilayer37. These second site mutations increased the reconstitution efficiency without significantly influencing the ΔF508-CFTR functional and biochemical phenotype17,37,38. Thermal inactivation of the phosphorylated ΔF508-CFTR-2RK was demonstrated by the progressive reduction of the open probability (Po) from 0.19 to 0.09 upon increasing the bilayer temperature from 24 to 36°C17,26 (Fig. 4e). In contrast, the WT Po increased from 0.31 to 0.44 during the temperature ramp (Fig. 4e). Acute addition of VX-809 delayed the thermal inactivation of ΔF508-CFTR resulting in a Po of 0.2 at 36°C17. Addition of 3C reversed the mutant thermal inactivation and conferred increased activity at 36°C (Po 0.45 ± 0.08, n= 11) similar to the WT (Fig. 4e,f and Supplementary Fig. 5g). The mean closed time of ΔF508-CFTR-2RK in presence of 3C was reduced from ~700 ms to 65 ms at 36°C, similar to that of the WT (Supplementary Fig. 5h), implying a near normal opening kinetics. In contrast to a single open state of the WT, ΔF508-CFTR-2RK exhibited a bimodal distribution of its mean open time. The 3C increased the prevalence of the longer openings at 36°C (Supplementary Fig. 5h). Taken together, these findings indicate that the 3C can confer thermal stability to the rescued ΔF508-CFTR functional conformation at 36°C, which is similar, but not identical, to that of the WT.

Functional correction of human CFTRΔF508/ΔF508 bronchial and nasal epithelia

To confirm the efficacy of corrector combinations in human tissue, CFTR function was monitored in primary HBE isolated from five individuals with CF homozygous for ΔF508 (CF-HBE) and from five non-CF donor lungs (WT-HBE) after differentiation at air-liquid interface (ALI). We confirmed that VX-809 increased the forskolin-activated and potentiated Isc of ΔF508-CFTR from 6% to 27% relative to that of WT-CFTR (Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Fig. 6a) as reported23,26,39. The best double combination (4172+VX-809) and 3C increased the ΔF508-CFTR Isc to 37% and 49% of the WT, respectively (Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Fig. 6a,b). Importantly, ΔF508-CFTR functional correction in CFBE41o- and CF-HBE cells was highly correlated, indicating the predictive capacity of the transduced CFBE41o- model for screening and mechanistic studies of CFTR modulators (Supplementary Fig. 6d). Corrector combinations also decreased the potentiator-dependent fraction of the forskolin-stimulated ΔF508-CFTR Isc (Fig. 5b, lower panel). The forskolin-activated Isc increased from 9% to 16% and 20% of WT, after correction with VX-809, 4172+VX-809 and 3C treatment, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6c).

Figure 5.

Corrector combinations rescue the ΔF508-CFTR function in human bronchial and nasal as well as mouse nasal epithelia. (a) Effect of indicated single correctors or corrector combinations on the Isc of primary human bronchial epithelia with CFTRΔF508/ΔF508 genotype (CF-HBE). (b) Quantification of the Fsk- and gen-stimulated current (ΔIsc Fsk + Gen, upper panel) in CF-HBE of five individuals homozygous for ΔF508 after single or combination of corrector treatment, expressed as percentage of WT-CFTR currents in WT-HBE from five donors. The fraction of potentiator independent Fsk-stimulated current is depicted in the lower panel. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by paired two-tailed Student’s t-test in comparison to VX-809 (the precise P-values are listed in Supplementary Table 4). (c,d) Effect of VX-809 or 3C on the Isc of human CF nasal epithelia (CF-HNE) isolated from seventeen individuals with CFTRΔF508/ΔF508 genotype. Quantification of the CFTRinh-172 inhibited current is depicted in d. 3C (Fsk) shows 3C corrected Isc stimulated with forskolin alone (cells from 12 individuals) and cVX-770, indicating chronic (37˚C, 24 hours, 1 μM, cells from 5 individuals) treatment with VX-770. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. (e) Correlation between the functional correction in CF-HBE (n = cells from 5 individuals) and CF-HNE (n = cells from 17 individuals). The Pearson correlation coefficient and the associated P-value are shown. (f,g) Nasal potential difference (Vt) measurements in ΔF508 Cftrtm1EUR mice. Representative Vt recordings before (f, left panel) and after treatments with 3C (f, right panel). After perfusion of nasal epithelium with Cl--containing solution (Cl-) Vt changes were monitored after sequential addition of 100 μM amiloride (Amil), low Cl- + Fsk (10 μM) and 5 μM CFTRinh-172. Summary of the ΔVt results for Low Cl- + Fsk and CFTRinh-172 for 8 mice in 3 independent experiments are shown in g. The mean values are indicated. (h) NPD results in ΔF508 Cftrtm1EUR mice (n = 8 animals) in comparison to WT-CFTR mice (n = 42 animals for basline and Δamiloride; n = 17 animals for Δlow Cl- + Fsk and Δ CFTRinh-172)46. ns, not significant, *P <0.05 by two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test (g-h). Data in b, d-e and h are means ± SEM. The precise P-values are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

A large inter-donor variation in the maximally stimulated Isc was documented in CF-HBE cells from homozygous ΔF508-CFTR patients as noted earlier26,39. Since a recent publication established a tight correlation between corrector effect in the more easily accessible patient-derived human nasal epithelia (CF-HNE) cells and the clinical outcome of corrector therapy40, we isolated HNE from 17 individuals with CF homozygous for ΔF508 (CF-HNE) and five non-CF donors (WT-HNE). HNE were amplified by the conditional reprogramming (CR) technique41,42 and characterized43. Similar to CF-HBE, VX-809 and 3C increased the forskolin-activated and potentiated ΔF508-CFTR Isc in CF-HNE from 10% to 28% and 48%, respectively, of WT-CFTR (Fig. 5c,d and Supplementary Fig. 6e). The relative rescue of Isc between CF-HBE and CF-HNE was strongly correlated, suggesting that HNE are a good surrogate model to measure CFTR function in CF individuals (Fig. 5e). The ΔF508-CFTR function in HNE after 3C ranged between 20% and 85% of the WT, significantly higher than after VX-809 treatment alone (Fig. 5d). For all individual homozygous ΔF508 CF-HNE the channel function after 3C exceeded the Isc achieved by VX-809 exposure (Supplementary Table 3). Similar to ΔF508-CFTR response in CF-HBE26,27, chronic treatment of CF-HNE with the gating potentiator VX-770 decreased the VX-809 corrector efficacy (Fig. 5d). This phenomenon was also observed in 3C treated CF-HNE. However, the remaining ΔF508-CFTR function, 34% of the WT, would likely still surpass the threshold required for clinical benefit (Fig. 5d).

Functional correction of ΔF508-CFTR in mice

Although less severe than in human, the ΔF508 mutation leads to a substantial folding defect of CFTR in mouse44. To determine the functional ΔF508-CFTR correction capacity of 3C in vivo, the corrector combination was topically instilled into the nose of ΔF508 Cftrtm1EUR mice45. While DMSO had no effect (Supplementary Fig. 7a), 3C exposure for 24 hours significantly increased the chloride secretion as determined by an increase in the low chloride and forskolin-stimulated trans-epithelial potential difference (Vt) from −1.0 mV to −2.9 mV, which corresponds to ~35% of the WT level46 in the absence of potentiator (Fig. 5f-h). The CFTR channel blocker CFTRinh-172 was able to inhibit the 3C restored chloride secretion, suggesting CFTR specificity. This inference was substantiated by the lack of 3C effect on nasal potential difference (NPD) in the CFTR knockout mouse strain CFTRtm1Unc (Supplementary Fig. 7b). These results suggest that topical administration of the 3C combination, even without potentiator, results in substantial correction of the ΔF508-CFTR current in vivo.

Allosteric rescue of some CFTR2 mutants by triple corrector combination

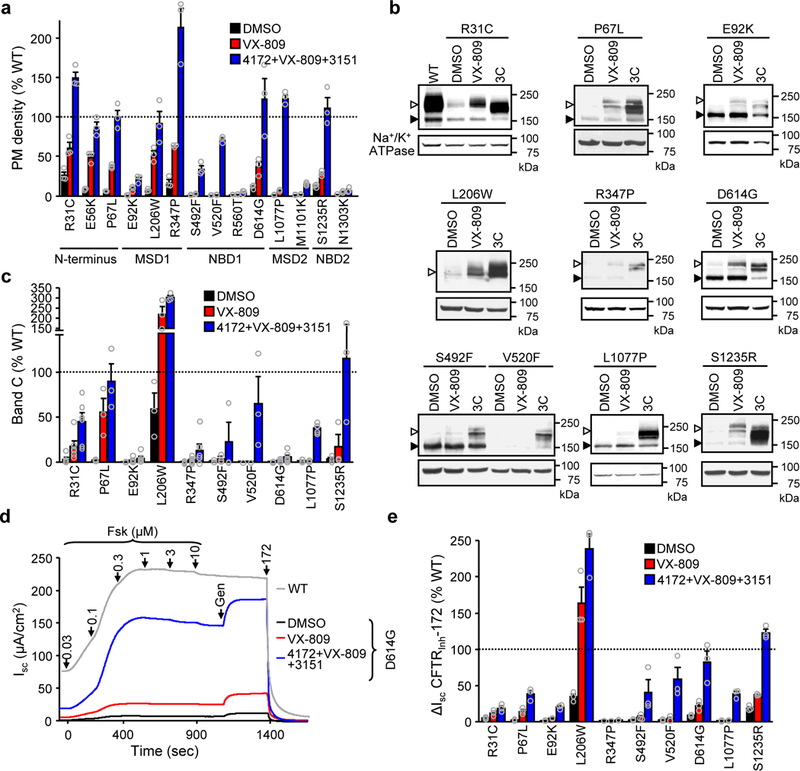

Cooperative domain folding and propagation of primary conformational defects to all structured domains caused by certain missense mutations distributed throughout CFTR15 raised the possibility of allosteric folding correction independent of the mutation location. To test this hypothesis, we determined the biochemical and functional rescue efficiency of fourteen CF mutants that were confined to the four structured domains and are associated with CFTR folding/processing defects1,47. The mRNA-normalized (Supplementary Fig. 8a) PM density of CFTR2 variants confirmed the various severity of CFTR expression defects in CFBE41o-, similar to that reported in FRT47. Remarkably, the PM density of all but three CFTR2 mutants was significantly increased to >25% of WT by 3C (Fig. 6a). Independent of the mutation location, combination of VX-809 with the type II (3151) and putative type III (4172) correctors yielded the highest correction efficacy at the PM level (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 8b). Comparable effect was detected by measuring the accumulation of complex-glycosylated CFTR2s in post-ER compartments (Fig. 6b,c).

Figure 6.

Rescue of rare CF folding mutants by allosteric corrector combination. (a) PM density of the indicated CFTR2 mutants alone and after VX-809 or 3C treatment expressed as percentage of WT-CFTR in CFBE41o- (n = 3). The domain localizations of the mutations are indicated. (b,c) Effect of VX-809 or 3C treatment on the expression pattern of CFTR2 mutants in CFBE41o- determined by immunoblot (b) and densitometric quantification (c, n = 6 for R31C, E92K, R347P, D614G, L1077P; n = 3 for P67L, L206W, S492F, V520F, S1235R). Uncropped immunoblots are presented in Supplementary Figure 11. (d,e) Effect of VX-809 or 3C on the Isc of CFTR2 mutants in CFBE41o-. Representative traces are shown in d. Mutant function (n = 3), expressed as percentage of WT function, is depicted in e. Data in a, c and e were normalized with mutant CFTR2 mRNA abundance (Supplementary Fig. 8a) and are means ± SEM of the indicated number of independent experiments.

Similar to ΔF508-CFTR, for some mutants, the fractional PM channel activity, defined as macroscopic function divided by CFTR PM density, did not reach the untreated WT level even after 3C and acute potentiator treatment (Supplementary Fig. 9a,b). Nevertheless, corrector combination increased the Isc (Fig. 6d,e and Supplementary Fig. 9a) and the potentiator-independent forskolin-activated Isc fraction for most mutants (Supplementary Fig. 9c). These results suggest that patients carrying a variety of folding mutations could benefit from corrector combinations that simultaneously stabilize distinct domains and/or domain interfaces, resulting in improved cooperative domain folding. This conclusion is supported by the increased trypsin resistance of the L1077P-CFTR at the full-length channel and individual domain levels in microsomes, isolated from 3C exposed cells (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Discussion

While significant research and drug development efforts19,23,30,48–50 have led to several clinical trials (Cystic fibrosis drug development pipeline: http://www.cff.org/trails/pipeline), until recently the only approved corrector drug for treating CF patients carrying two copies of the ΔF508 mutation was VX-809 (lumacaftor), in combination with the gating potentiator VX-770 (ivacaftor)25. VX-809, however, has only modest clinical benefit since in combination with VX-770 (2.6–4% absolute gain of predicted FEV1%)25 it can restore just ~25% of the WT-CFTR function in homozygous ΔF508 primary CF-HBE cells23. VX-661 (tezacaftor), which has a similar efficacy in CF-HBE cells26 and in combination with VX-770 resulted in comparable gain in lung function in homozygous ΔF508 patients (4% absolute gain of predicted FEV1%)22, was approved in February 2018. Using biochemical screens in combination with VX-809 or a suppressor mutation (R1070W), here we identified novel, mechanistically distinct corrector compounds, that target individual components of the complex structural defects of ΔF508-CFTR. By rationale selection of compounds targeting three kinds of conformational defects of ΔF508-CFTR, the 3C resulted in complete (103%) biochemical and ~48% functional restoration of ΔF508-CFTR relative to WT and partial alleviation of the potentiator requirement. The conformational stability of the 3C corrected NBD2, MSD1 and MSD2 and full-length ΔF508-CFTR, probed by limited trypsinolysis, became comparable to that of the WT, suggesting that major conformational defects do not persist in the corrected ΔF508-CFTR. Meanwhile, the incomplete functional rescue by the 3C suggests that pharmacological chaperone-assisted folding may trap ΔF508-CFTR in a stable, but partially functional state and/or that the macromolecular signalling complex of ΔF508-CFTR at the PM51,52 is only partly assembled. In conjunction with the small inhibitory effect of some of the corrector molecules, this may explain the reduced fractional channel activity.

Mechanistic clustering of hits identified compound 4172, as a putative type III corrector, with a binding affinity to isolated ΔF508-NBD1 of ~40 μM and an EC50 of ~3 μM for functional increase of ΔF508-CFTR in epithelial cells. This increased in vivo potency of 4172 may be explained by the intracellular accumulation or enhanced affinity to the full-length CFTR. The most effective ΔF508-CFTR biochemical and functional correction was achieved when 4172 treatment was combined with type I (VX-809 or 6258) and type II (3151) correctors that act on NBD1-MSDs and NBD2, respectively. 3151 structurally resembles the previously described aminothiazol compounds, C4 and D-01 (refs. 17,19,30). These results substantiate the prediction9,10,17 that combining correctors targeting distinct structural defects can overcome their limited individual efficacies and robustly rescue the ΔF508-CFTR folding defect.

While the precise binding sites of the identified correctors remain to be elucidated, functional stabilization of single ΔF508-CFTR channels close to the WT in phospholipid bilayer38 suggests that these compounds act by directly binding to and promoting the folding and/or native conformer stability of ΔF508-CFTR as pharmacological chaperones. The lack of stabilization of several conformationally defective PM proteins by 3C, while having significant rescue efficacy of ΔF508-CFTR in CFBE41o- cells, primary CF-HBE, CF-HNE and on the NPD in ΔF508 Cftrtm1EUR mice also favours their pharmacochaperone-like activity over indirect effect via the perturbation of cellular proteostasis. The implication of latter results is that the CFBE41o- model, heterologously expressing tagged CFTR variants, has a predictive value and can serve as an authentic model for corrector selection for drug resistant mutations.

The 3C also elicited near complete biochemical correction of several rare CFTR folding mutants that display modest susceptibility to VX-809 and no clear correlation between the correction level and the mutation localization. The requirement of corrector-mediated interaction with multiple domains and interfaces of the mutant to achieve robust ΔF508-CFTR correction also in line with the highly cooperative folding and misfolding processes of CFTR14,15, which permit allosteric correction of the global conformation defect elicited by other missense CF mutation located in the MSD1, MSD2, NBD1 or NBD2. Based on this observation, we predict other VX-809-resistant missense mutations may be susceptible to combinatorial corrector rescue as well.

To increase the correction efficacy of ΔF508-CFTR several strategies were devised, including the identification and manipulation of modifier genes39,53–55, as well as altering cellular proteostasis activity, including modulation of chaperone or autophagy activities56–59. Our approach, to target distinct ΔF508-CFTR folding defects with combinations of pharmacological chaperones, was able to restore homozygous ΔF508-CFTR function to ~50% of the WT level, a value that is deemed sufficient to alleviate clinical manifestations in half of CF patients, since heterozygous carriers lack disease symptoms60. Moreover, the achieved correction level would likely provide benefit to the 40% compound heterozygous CF patients that carry the ΔF508 mutation in one allele and possibly to CF patients with rare folding mutations with a non-responsive (e.g. premature termination codon) mutation on the second allele.

Online Methods

Antibodies and reagents

Mouse monoclonal anti–hemagglutinin (HA) antibody was purchased from Covance. Monoclonal anti-CFTR antibody M3A7 (recognizing aa 1365–1395 at the C terminus of the NBD2) and MM13–4 mouse monoclonal anti-CFTR Ab (specific to the N-terminal 25–36 residues) were from Millipore. The 660 anti-CFTR antibody, recognizing the NBD114, was kindly provided by Dr. J. Riordan (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC). VX-770 and VX-809 were purchased from Selleckchem. For follow up studies, the small molecule corrector compounds were acquired from Life chemicals (4172 and 3151 series as well as BIA29) or Maybridge (6258 series) and their identity was confirmed by mass spectrometry. All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich at the highest grade available.

Cell lines

Full-length human WT- or ΔF508-CFTR with a 3HA-tag or HRP-tag in the fourth extracellular loop have been described17,26. Nucleotide substitutions to generate other CFTR variants and second site mutations were introduced by overlapping PCR mutagenesis as described before16. The generation of CFBE41o- [a gift from D. Gruenert, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)] cell lines expressing inducible CFTR variants has been described previously61.

CFBE41o- cells were maintained in MEM medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen), 2 mM l-glutamine and 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES). For experiments the expression of CFTR variants was induced for ≥ 3 days with 500 ng/ml doxycycline.

Human bronchial and nasal epithelia

Human bronchial epithelia (HBE) cells isolated from the bronchi following lung transplantation of CF and non-CF individuals were a gift from Dr. W. Finkbeiner [University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)] or were purchased from the Cystic Fibrosis Translational Research center (CFTRc) at McGill University. The isolation of human nasal epithelia (HNE) from healthy and CF human subjects was performed under the protocol and consent form approved by the McGill MUHC Research Ethics Board (14–234-BMB). All relevant ethical regulations were followed. Tissue collection and HNE cell isolation was performed as described42. Both HBE and HNE cells were conditionally reprogrammed62 followed by differentiation on Snapwell filter supports63.

Mouse strains

Congenic mice homozygous for the ΔF508 mutation, ΔF508 Cftrtm1EUR (FVB/N background)64, as well as homozygous knockout Cftr mice, KO CFTRtm1Unc (B6;129 background) and their wild-type littermates were obtained from CDTA (Cryopreservation, Distribution, Typage et Archivage animal, Orléans, France), and housed at Animal Care Facility of Institut Necker Enfants Malades, Paris. Mice were fed with fiber-free diet and a laxative was used in their drinking water (Colopeg 17.14 g/l; Bayer Santé Familiale, France) to avoid intestinal obstruction. Experiments were approved by the local committee for animal experiments (Comité Régional d’Ethique sur l’expérimentation animale Ile de France Sud-MESR N° 01345.03). All relevant ethical regulations were followed.

PM density measurement

The PM density of HRP-tagged CFTR variants was measured by luminometry after addition of HRP substrate. The PM density of 3HA-tagged proteins was determined by cell surface enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)55. PM density measurements were normalized with cell viability determined by alamarBlue Assay (Invitrogen).

Halide-sensitive YFP quenching assay

CFTR function by halide-sensitive YFP quenching assay was performed as described previously26. Briefly, CFBE41o- cells harbouring the inducible expression of ΔF508-CFTR were generated to co-express the halide sensor YFP-F46L/H148Q/I152L65 by lentiviral transduction followed by clonal isolation. YFP-expressing cells, seeded onto 96-well microplates at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well, were induced for ΔF508-CFTR expression for 4 days at 37°C. During the assay the CFBE41o- cells were incubated in 50 μl per well phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-chloride (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 1.1 mM MgCl2, 0.7 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM glucose, pH 7.4) at 32˚C. The assay was performed well-by-well. At 0 seconds CFTR was activated by 50 μl injection of activator solution [20 μM forskolin, 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methyl-xanthine (IBMX), 0.5 mM 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-adenosine-3’,5’-cyclic monophosphate (cpt-cAMP), 100 μM genistein] in PBS. The quenching reaction was started at 60 seconds by injection of 100 μl of PBS-iodide, in which NaCl was replaced with NaI. YFP-fluorescence (485-nm excitation and 520-nm emission) was recorded between 57 and 93 seconds with a 5-Hz data acquisition rate in a POLARstar OPTIMA (BMG Labtech) fluorescence plate reader. Background values were subtracted and the YFP signal was normalized to the fluorescence before NaI injection. The iodide influx rates were calculated by linear fitting to the initial slope after iodide addition starting from 61 seconds to exclude the instantaneous quenching artefact upon NaI injection during the first second.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

To allow for in vivo biotinylation in E. coli, the AviTag (Avidity) was fused in frame to the N-terminus of CFTR-NBD1 variants. NBD1 proteins were expressed in BL21 codon+ (Agilent) and purified as described previously9. The mass and purity of the recombinant NBD1 protein preparations was verified by SDS-PAGE and MALDI mass spectrometry. Binding interactions between biotinylated NBD1 constructs (WT-, ΔF508–1S-, ΔF508–3S-NBD1) and corrector compounds (250–480 Da) were examined with a BIACORE T200 system (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB) using S-series CM5 sensors, similarly as described by Hall and coworkers13. According to the manufacturer’s instructions (GE Healthcare), neutravidin (5 mg/mL in water, diluted to 50 μg/mL in 10 mM sodium acetate pH 5.0) was amine-coupled to all flow cells (~15,000 RU each) at 25°C using filtered (0.2 μm) and degassed HBS-EP buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 3 mM EDTA; 0.005% (v/v) Tween-20). Subsequently cooled to 4°C (sample chamber and sensor) and equilibrated in PBS running buffer (1X PBS pH 7.4 containing 10% (v/v) glycerol, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 0.05% (v/v) Tween20), reference (neutravidin only) and active surfaces (100 μg/mL NBD1 constructs in PBS buffer; capture 5000–8000 RU each) were equilibrated in PBS buffer containing 2% (v/v) DMSO at 10 μL/min. The corrector compounds were titrated over reference and NBD1-immobilized surfaces at 25–50 μL/min (1–2 minute association + 2–5 min dissociation; 2-fold dilution series for all compounds). Between titration series, the surfaces were regenerated at 50 μL/min using two 30 sec pulses of solution I (PBS-DMSO buffer containing 1.0 M NaCl and 0.05% (v/v) Empigen). The rapid, steady-state binding responses were independent of mass transport limitations and subjected to DMSO solvent correction. All double-referenced data66 presented are representative of duplicate injections acquired from at least three independent trials. The observed signal maxima were verified against theoretical binding maxima as predicted by the equation: Rmax = MWA / MWL * RL * n where Rmax is the maximal binding response (RU) at saturating compound concentration; MWA is the molecular mass (kDa) of the injected compound; MWL is the molecular mass (kDa) of the imm obilized NBD1 protein; RL is the amount (RU) of immobilized NBD1; and n is the predicted binding stoichiometry (e.g. 1:1). To predict overall equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) for each NBD1 construct, steady-state binding responses (Req) were averaged near the end of each association phase, plotted as a function of CFTR corrector concentration (C), and then subjected to non-linear regression analysis in the T200 evaluation software (“Steady state affinity” model).

qPCR

Total RNA was isolated using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) followed by reverse transcription with the QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen). The abundance of transcripts was determined using RT2 SYBR Green Rox Fast qPCR premix (Qiagen) with an Mx3005P real-time cycler (Stratagene). CFTR was detected with the following primers: sense gaggaaaggatacagacagcgcctg and antisense gaagccagctctctatcccattc. Variations in RNA loading amount were accounted for by normalizing to GAPDH (sense primer catgagaagtatgacaacagcct, antisense primer agtccttccacgataccaaagt).

Metabolic pulse-chase

Experiments were performed essentially as described9. Briefly, 24 hours after start of compound treatment, CFBE41o- cells expressing WT- or ΔF508-CFTR were pulse-labeled with 0.2 mCi/ml 35S-methinonine and 35S-cysteine (EasyTag Express Protein Labeling Mix, PerkinElmer) in cysteine and methionine-free medium for 20 minutes at 37°C or labeled for 40 minutes and then chased 2.5 hours at 37°C in full medium. Radioactivity incorporated into the core- and complex-glycosylated glycoproteins was visualized by fluorography and quantified by phosphoimage analysis using a Typhoon imaging platform (GE Healthcare). The maturation efficiency was determined by calculating the percent of pulse-labeled immature, core-glycosylated CFTR conversion into the mature, complex-glycosylated form after 2.5 hours of chase.

Limited trypsinolysis

Microsomes containing ER, Golgi, endosome and plasma membrane–enriched vesicles were isolated by nitrogen cavitation and differential centrifugation from BHK-2116 overexpressing the indicated CFTR variants and treated with the indicated corrector or DMSO for 24 hours. To eliminate the core glycosylated form, BHK-21 cells expressing CFTR variants were treated with cycloheximide (150 μg/ml): WT-CFTR for 150 minutes, ΔF508-CFTR + VX-809 for 45 minutes, ΔF508-CFTR + 3C and L1077P-CFTR + 3C for 120 minutes. Microsomes were resuspended in 10 mM HEPES, 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.6 and used either immediately or after snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen.

Microsomes (1–2 mg/ml protein) were digested at the indicated concentration of TPCK treated trypsin (Worthington) for 15 min on ice. Proteolysis was terminated by addition of 2 mg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma), 0.4 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM PMSF, 2 μg/ml leupeptin and pepstain. After addition of Laemmli’s sample buffer, digested microsomes were subjected to immunoblot analysis using CFTR domain-specific antibodies.

Short-circuit current measurement

Short-circuit current measurement of polarized CFBE41o-61 and HBE26 has been described previously. Briefly, for short-circuit current measurements CFBE41o- cells were grown on ECM-mix coated 12 mm Snapwell filters (Corning) and the CFTR expression was induced for ≥ 4 days with 500 ng/ml doxycycline. HBE and HNE were differentiated on collagen IV coated Snapwell filters under air-liquid interface conditions in Ultroser G (Pall) medium63 for ≥ 4 weeks. The Snapwell filters were mounted in Ussing chambers (Physiologic Instruments) in Krebs-bicarbonate Ringer buffer (140 mM Na+, 120 mM Cl−, 5.2 mM K+, 25 mM HCO3−, 2.4 mM HPO4, 0.4 mM H2PO4, 1.2 mM Ca2+, 1.2 mM Mg2+, 5 mM glucose, pH 7.4) which was mixed by bubbling with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. For CFBE41o- and HNE cells apical NaCl was replaced with Na+ gluconate to generate a chloride gradient. The CFBE41o- basolateral membrane was permeabilized with 100 μM amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich). Under those conditions the transepithelial resistance (Rt) was 1433 ± 225 Ω*cm2 (n = 3), 406 ± 54 Ω*cm2 (n = 5) and 552 ± 60 Ω*cm2 (n = 17) for CFBE41o-, CF-HBE and CF-HNE, respectively. After compensating for voltage offsets, the transepithelial voltage was clamped at 0 mV and measurements were recorded with the Acquire and Analyze package (Physiologic Instruments). Measurements were performed at 37°C in the presence of 100 μM amiloride. CFTR-mediated currents were induced by sequential acute addition of increasing concentrations of forskolin (0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10 μM) and genistein (50 μM) or VX-770 (10 μM) followed by CFTR inhibition with CFTRinh-172 (20 μM).

CFTR reconstitution in BLM

Microsomes containing WT- or ΔF508-CFTR-2RK were isolated from stably transfected BHK-21 cell and reconstituted in BLM as described38,67. Briefly, ΔF508-CFTR-2RK expressing cells were cultured at 26°C for 36 hours. Before the isolation of microsomes, ΔF508 and WT cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX, 150 μg/ml) for 14 hours at 26°C and 3 hours at 37°C, respectively. Planar lipid bilayer composition was 2:1 of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE) and 1-palmitoyl-2- oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (POPS) (Avanti Lipids) at 25 mg/ml final lipid concentration in n-decane solution. Cis and trans cups contained 0.8–1 ml symmetrical buffer solutions (300 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM EGTA) with or without corrector compounds. In addition, the cis-side cup contained 2 mM ATP and 100 U/ml PKA catalytic subunit (Promega). Microsomes were also prephosphorylated with the PKA catalytic subunit and 2 mM MgATP for 10 minutes at room temperature before addition to cup38,67.

CFTR currents were measured by using the BC-535 amplifier (Warner Instrument) and pClamp 10.3 data acquisition system (Axon Instruments) at −60 mV holding potential. Signals were low pass filtered at 200 Hz by an 8-pole Bessel filter, and digitized at 10 kHz by Digidata 1320 (Axon Instruments). Temperature was increased between 23°C and 37°C using the CL-100 temperature controller (Warner Instrument) at ∼1.4 °C min−1 rate. Channel open probability (Po) was determined after digitally filtering at 50 Hz by analysis of records with the Clampfit 10.3 software. The Po values, mean closed and mean open times of untreated ΔF508-CFTR-2RK and WT-CFTR have been published before38 and are only shown for comparison.

NPD measurement

For NPD measurements mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (133 mg/kg; IMALGENE 1000, MERIAL, France) and xylazine (13.3 mg/kg; Rompun 2%, BayerPharma, France).

20 μl of Vehicle DMSO (0,6% diluted in PBS) was administered topically by gentle nasal instillation at day 0, the 3C combination (4172 (20 μM) + VX-809 (6 μM) + 3152 (20 μM)) diluted in DMSO was administered at day 7 in the same animals. NPD was measured 24h after each instillation as previously described68 with minor modifications. Briefly, the trans-epithelial potential difference (Vt) was assessed between a reference Ag/Ag reference electrode and an exploring Ag/AgCl electrode connected to the nasal mucosa through a double-lumen polyethylene catheter. One lumen of the catheter was filled with Cl- solution: HEPES-Krebs-buffer (140 mM NaCl, 6 mMKCl, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, pH adjusted to 7.4). The following solutions were perfused through the second lumen: Cl- solution for baseline Vt measurement, 100 μM amiloride in Cl- solution (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) to block ENaC Na+ absorption, low-Cl- solution (where 140 mM NaCl, 6 mM KCl and 2 mM CaCl2 were replaced by 140 mM sodium gluconate, 6 mM potassium gluconate and 2 mM calcium gluconate, respectively) supplemented with forskolin 10μM (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) to activate CFTR and drive Cl- secretion, and a low Cl- solution supplemented with forskolin and 5μM of CFTRinh-172 to inhibit CFTR activation. Vt was recorded using an averaging analog to digital converter supplied by Logan Research Ltd, Rochester, Kent, UK.

Four parameters were investigated during NPD measurements: The maximal baseline Vt assessed during Cl- solution perfusion (Baseline Vt), the successive net voltage changes between baseline Vt and the Cl- solution containing amiloride (Δamiloride), between Cl- solution containing amiloride and low-Cl- solution containing amiloride plus forskolin (Δlow Cl-+fsk) and between low-Cl- solution containing amiloride + forskolin and low-Cl- solution containing amiloride + forskolin + CFTRinh-172 (ΔInh172).

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise specified, statistical analysis was performed by two-tailed Student’s t-test with the means of at least three independent experiments and the 95% confidence level was considered significant. Dose-response plots were fitted with a sigmoidal dose-response equation using OriginPro 8.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for individuals who volunteered to participate in this study. We thank D.C. Gruenert for the parental CFBE41o- cell line; W.E. Finkbeiner for supplying HBE cells, J. Riordan and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation for the 660 antibody, P. Thomas for providing vectors encoding some of the CFTR2 mutants and members of the Cystic Fibrosis Folding Consortium for advice. This work was supported by Vaincre La Mucoviscidose to A.E. and I.S.-G., the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-142221 to G.L.L. and PJT-153095 to G.V., E.M., and G.L.L.), National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases (5R01DK075302 to G.L.L.), the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics to G.L.L., as well as Cystic Fibrosis Canada to G.L.L. We acknowledge the Canada Foundation for Innovation for infrastructure support: Bruker UltrafleXtreme MALDI-TOF/TOF system (grant #32616, awarded to G. Multhaup and G.L.L.); BIACORE T200 SPR system (grant #228340 awarded to G. Multhaup). R.G.A. is a recipient of the Fonds de Recherche du Québec Santé (FRQS) Doctoral Training Scholarship. G.L.L. is a Canada Research Chair.

Footnotes

Reporting Summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing financial interests

C.L., W.L., K.M., S.G., P.A.M., F.J.K., E.A., A.J.O., P.M. and W.G.B. are employees of the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation. I.S.-G. has been principal investigator in Vertex initiated clinical trials, received a Vertex Pharmaceuticals Innovation Award and served as a scientific advisory board member for Vertex Pharmaceuticals. G.L.L. is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Proteostasis Therapeutics Inc. All other authors declare no competing financial or non-financial interests.

References

- 1.Veit G, et al. From CFTR biology toward combinatorial pharmacotherapy: expanded classification of cystic fibrosis mutations. Molecular biology of the cell 27, 424–433 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sosnay PR, et al. Defining the disease liability of variants in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene. Nat Genet 45, 1160–1167 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cutting GR Cystic fibrosis genetics: from molecular understanding to clinical application. Nat Rev Genet 16, 45–56 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu F, Zhang Z, Csanady L, Gadsby DC & Chen J Molecular Structure of the Human CFTR Ion Channel. Cell 169, 85–95 e88 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt JF, Wang C & Ford RC Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (ABCC7) structure. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 3, a009514 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hwang TC & Kirk KL The CFTR ion channel: gating, regulation, and anion permeation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 3, a009498 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chong PA, Kota P, Dokholyan NV & Forman-Kay JD Dynamics intrinsic to cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator function and stability. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 3, a009522 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okiyoneda T, Apaja PM & Lukacs GL Protein quality control at the plasma membrane. Curr Opin Cell Biol 23, 483–491 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabeh WM, et al. Correction of both NBD1 energetics and domain interface is required to restore ΔF508 CFTR folding and function. Cell 148, 150–163 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendoza JL, et al. Requirements for efficient correction of ΔF508 CFTR revealed by analyses of evolved sequences. Cell 148, 164–174 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farinha CM, et al. Revertants, low temperature, and correctors reveal the mechanism of F508del-CFTR rescue by VX-809 and suggest multiple agents for full correction. Chem Biol 20, 943–955 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He L, et al. Restoration of NBD1 thermal stability is necessary and sufficient to correct F508 CFTR folding and assembly. J Mol Biol 427, 106–120 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall JD, et al. Binding screen for cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator correctors finds new chemical matter and yields insights into cystic fibrosis therapeutic strategy. Protein Sci 25, 360–373 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui L, et al. Domain interdependence in the biosynthetic assembly of CFTR. J Mol Biol 365, 981–994 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du K & Lukacs GL Cooperative assembly and misfolding of CFTR domains in vivo. Mol Biol Cell 20, 1903–1915 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du K, Sharma M & Lukacs GL The ΔF508 cystic fibrosis mutation impairs domain-domain interactions and arrests post-translational folding of CFTR. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12, 17–25 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okiyoneda T, et al. Mechanism-based corrector combination restores ΔF508-CFTR folding and function. Nat Chem Biol 9, 444–454 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vernon RM, et al. Stabilization of a nucleotide-binding domain of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator yields insight into disease-causing mutations. J Biol Chem 292, 14147–14164 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phuan PW, et al. Synergy-based Small-Molecule Screen Using a Human Lung Epithelial Cell Line Yields DeltaF508-CFTR Correctors that Augment VX-809 Maximal Efficacy. Mol Pharmacol 86, 42–51 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopes-Pacheco M, et al. Combination of Correctors Rescue DeltaF508-CFTR by Reducing Its Association with Hsp40 and Hsp27. J Biol Chem 290, 25636–25645 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Loo TW, Bartlett MC & Clarke DM Additive effect of multiple pharmacological chaperones on maturation of CFTR processing mutants. Biochem J 406, 257–263 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor-Cousar JL, et al. Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis Homozygous for Phe508del. N Engl J Med 377, 2013–2023 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Goor F, et al. Correction of the F508del-CFTR protein processing defect in vitro by the investigational drug VX-809. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108, 18843–18848 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren HY, et al. VX-809 corrects folding defects in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein through action on membrane-spanning domain 1. Mol Biol Cell 24, 3016–3024 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wainwright CE, et al. Lumacaftor-Ivacaftor in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis Homozygous for Phe508del CFTR. N Engl J Med 373, 220–231 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veit G, et al. Some gating potentiators, including VX-770, diminish ΔF508-CFTR functional expression. Sci Transl Med 6, 246ra297 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cholon DM, et al. Potentiator ivacaftor abrogates pharmacological correction of DeltaF508 CFTR in cystic fibrosis. Sci Transl Med 6, 246ra296 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehrhardt C, et al. Towards an in vitro model of cystic fibrosis small airway epithelium: characterisation of the human bronchial epithelial cell line CFBE41o. Cell Tissue Res 323, 405–415 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thibodeau PH, et al. The cystic fibrosis-causing mutation deltaF508 affects multiple steps in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator biogenesis. J Biol Chem 285, 35825–35835 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedemonte N, et al. Small-molecule correctors of defective DeltaF508-CFTR cellular processing identified by high-throughput screening. J Clin Invest 115, 2564–2571 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pissarra LS, et al. Solubilizing mutations used to crystallize one CFTR domain attenuate the trafficking and channel defects caused by the major cystic fibrosis mutation. Chem Biol 15, 62–69 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Apaja PM, Xu H & Lukacs GL Quality control for unfolded proteins at the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol 191, 553–570 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duarri A, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of megalencephalic leukoencephalopathy with subcortical cysts: mutations in MLC1 cause folding defects. Hum Mol Genet 17, 3728–3739 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takahashi K, et al. V2 vasopressin receptor (V2R) mutations in partial nephrogenic diabetes insipidus highlight protean agonism of V2R antagonists. J Biol Chem 287, 2099–2106 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Apaja PM, et al. Ubiquitination-dependent quality control of hERG K+ channel with acquired and inherited conformational defect at the plasma membrane. Mol Biol Cell 24, 3787–3804 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang F, Kartner N & Lukacs GL Limited proteolysis as a probe for arrested conformational maturation of delta F508 CFTR. Nat Struct Biol 5, 180–183 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hegedus T, et al. F508del CFTR with two altered RXR motifs escapes from ER quality control but its channel activity is thermally sensitive. Biochim Biophys Acta 1758, 565–572 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bagdany M, et al. Chaperones rescue the energetic landscape of mutant CFTR at single molecule and in cell. Nat Commun 8, 398 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veit G, et al. Ribosomal Stalk Protein Silencing Partially Corrects the DeltaF508-CFTR Functional Expression Defect. PLoS Biol 14, e1002462 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pranke IM, et al. Correction of CFTR function in nasal epithelial cells from cystic fibrosis patients predicts improvement of respiratory function by CFTR modulators. Sci Rep 7, 7375 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu X, et al. Conditional reprogramming and long-term expansion of normal and tumor cells from human biospecimens. Nat Protoc 12, 439–451 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muller L, Brighton LE, Carson JL, Fischer WA 2nd, & Jaspers I, Culturing of human nasal epithelial cells at the air liquid interface. J Vis Exp, e50646 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Avramescu RG, et al. Mutation-specific downregulation of CFTR2 variants by gating potentiators. Hum Mol Genet 26, 4873–4885 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ostedgaard LS, et al. Processing and function of CFTR-DeltaF508 are species-dependent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 15370–15375 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.French PJ, et al. A delta F508 mutation in mouse cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator results in a temperature-sensitive processing defect in vivo. J Clin Invest 98, 1304–1312 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.da Cunha MF, et al. Analysis of nasal potential in murine cystic fibrosis models. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 80, 87–97 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Goor F, Yu H, Burton B & Hoffman BJ Effect of ivacaftor on CFTR forms with missense mutations associated with defects in protein processing or function. J Cyst Fibros 13, 29–36 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robert R, et al. Correction of the Delta phe508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator trafficking defect by the bioavailable compound glafenine. Mol Pharmacol 77, 922–930 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coffman KC, et al. Constrained bithiazoles: small molecule correctors of defective DeltaF508-CFTR protein trafficking. J Med Chem 57, 6729–6738 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rowe SM & Verkman AS Cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator correctors and potentiators. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 3(2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li C & Naren AP CFTR chloride channel in the apical compartments: spatiotemporal coupling to its interacting partners. Integr Biol (Camb) 2, 161–177 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Monterisi S, et al. CFTR regulation in human airway epithelial cells requires integrity of the actin cytoskeleton and compartmentalized cAMP and PKA activity. J Cell Sci 125, 1106–1117 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pankow S, et al. F508 CFTR interactome remodelling promotes rescue of cystic fibrosis. Nature 528, 510–516 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trzcinska-Daneluti AM, et al. RNA interference screen to identify kinases that suppress rescue of deltaF508-CFTR. Mol Cell Proteomics 14, 1569–1583 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Okiyoneda T, et al. Peripheral protein quality control removes unfolded CFTR from the plasma membrane. Science 329, 805–810 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tosco A, et al. A novel treatment of cystic fibrosis acting on-target: cysteamine plus epigallocatechin gallate for the autophagy-dependent rescue of class II-mutated CFTR. Cell Death Differ 23, 1380–1393 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roth DM, et al. Modulation of the maladaptive stress response to manage diseases of protein folding. PLoS Biol 12, e1001998 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hegde RN, et al. Unravelling druggable signalling networks that control F508del-CFTR proteostasis. Elife 4, pii: e10365 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Calamini B, et al. Small-molecule proteostasis regulators for protein conformational diseases. Nat Chem Biol 8, 185–196 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Griesenbach U, Geddes DM & Alton EW The pathogenic consequences of a single mutated CFTR gene. Thorax 54 Suppl 2, S19–23 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Methods-only References

- 61.Veit G, et al. Proinflammatory cytokine secretion is suppressed by TMEM16A or CFTR channel activity in human cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelia. Mol Biol Cell 23, 4188–4202 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu X, et al. ROCK inhibitor and feeder cells induce the conditional reprogramming of epithelial cells. The American journal of pathology 180, 599–607 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neuberger T, Burton B, Clark H & Van Goor F Use of primary cultures of human bronchial epithelial cells isolated from cystic fibrosis patients for the pre-clinical testing of CFTR modulators. Methods Mol Biol 741, 39–54 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Doorninck JH, et al. A mouse model for the cystic fibrosis delta F508 mutation. EMBO J 14, 4403–4411 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Namkung W, Thiagarajah JR, Phuan PW & Verkman AS Inhibition of Ca2+-activated Cl- channels by gallotannins as a possible molecular basis for health benefits of red wine and green tea. FASEB J 24, 4178–4186 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Myszka DG Improving biosensor analysis. J Mol Recognit 12, 279–284 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aleksandrov AA & Riordan JR Regulation of CFTR ion channel gating by MgATP. FEBS Lett 431, 97–101 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saussereau EL, et al. Characterization of nasal potential difference in cftr knockout and F508del-CFTR mice. PLoS One 8, e57317 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.