Abstract

Background:

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a transitional phase between healthy cognition and dementia. Physical activity (PA) has protective effects on cognitive decline. However, few studies have examined how PA and sedentary behavior is structured throughout the day in older adults across varied cognitive status in Hong Kong.

Objective:

This study aimed to compare patterns of PA and sedentary behavior among individuals with AD, MCI or normal cognition living in Hong Kong.

Methods:

Participants in the MrOs and MsOs Hong Kong cohort study and the Hong Kong AD biomarker study (n=810) wore a wrist-worn accelerometer for 7 days in free-living environment. Patterns of PA in wake time and in-bed time, and detailed analysis of sedentary bouts were compared between groups using analysis of covariance adjusting for covariates.

Results:

Participants with MCI and low MoCA only did not differ from their cognitively normal peers in PA and sedentary behavior. Nevertheless, when comparing to the others, participants with AD exhibited significantly lower average daily counts per minute during the day (p < 0.05), and tended to start their activity later in the morning. AD participants spent a larger proportion of time in sedentary behavior (p < 0.05) and had more sedentary bouts ≥ 30 minutes (p < 0.05).

Conclusions:

The pattern of PA and sedentary behavior was different between individuals with AD and the others. Cognitive status may alter the purpose and type of PA intervention for AD individuals.

Keywords: Accelerometry, exercise, Cognitive decline, Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment

INTRODUCTION

Dementia is a syndrome that causes typically leads to a loss of independence, reduced quality of life, premature mortality, caregiver burden and high levels of healthcare utilization and cost [1]. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia, and the prevalence of AD is increasing dramatically with the ageing population [2]. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is usually described as a transitional phase between healthy cognition and dementia [3]. It is estimated that the annual rate of progression from MCI to dementia ranging from 5% to 15%, varying according to different settings, while a large proportion of individuals with MCI do not experience further deterioration of cognitive function [4].

Physical activity (PA) has been identified as a life-course potential modifiable risk factor for AD [5]. PA can increase blood flow to the brain, improve cardiovascular and metabolic health, and simultaneously encourage cognitive and social activities, which may have beneficial effects on brain health [6]. PA has been consistently associated with beneficial effects on cognition [7–10]. Some studies have also reported that PA may improve memory and delay the decline in cognitive function among individuals with MCI [11, 12]. While the current evidence points to a need for PA interventions among individuals with cognitive impairment, a next step is to better understand how the patterns of PA for individuals with AD or MCI would differ from those with healthy cognition.

The recent availability of accelerometers permits a detailed investigation of daily PA among older adults. Accelerometers can measure PA continuously in free-living environment and reduce the impact of recall bias or memory loss, a particular concern in older adults with cognitive impairment [15]. Accelerometers provide a great opportunity to assess activity across the full range of intensity. Previous studies have shown that individuals with MCI or dementia had fewer total daytime activity counts than individuals without dementia [16, 17]. However, only focusing on the amount of PA failed to describe how PA was structured over the course of the day and did not consider sleep. A few studies have explored the association between cognitive function and diurnal patterns of PA [18–21], but most of these studies were limited to institutionalized individuals, who were less active than community-dwelling older adults with dementia [18–20].

Targeting reduction in sedentary behavior might be another option to prevent cognitive decline. Increasing evidence also suggests that sedentary behavior is associated with cognitive impairment and all-cause dementia risk [13]. The construct of sedentary behavior is defined as any waking behavior with an energy expenditure ≤ 1.5 METs while in a sitting or reclining posture [14]. However, few studies have reported on how sedentary behavior was different between people with or without cognitive decline. Therefore, a more in-depth investigation of sedentary patterns is needed.

To our knowledge, no previous studies on patterns o PA and sedentary behavior have considered individuals with AD, MCI and cognitively normal simultaneously, and few studies have described older adults in Hong Kong, who may have significantly different lifestyle, diet, and body physiology compared to Caucasian or other ethnic population. Thus, we measured PA continuously by accelerometers in older adults with normal cognition, MCI and AD, and compared their average daily PA and patterns during waking hours and in-bed time. We expected that patterns of PA over the course of the day for the three cognitive status would vary from each other. In addition, we further compared patterns of sedentary behavior (numbers and duration of bouts) among the cognition groups and aimed to provide comprehensive information on the PA of older adults in Hong Kong.

METHODS

Study participants

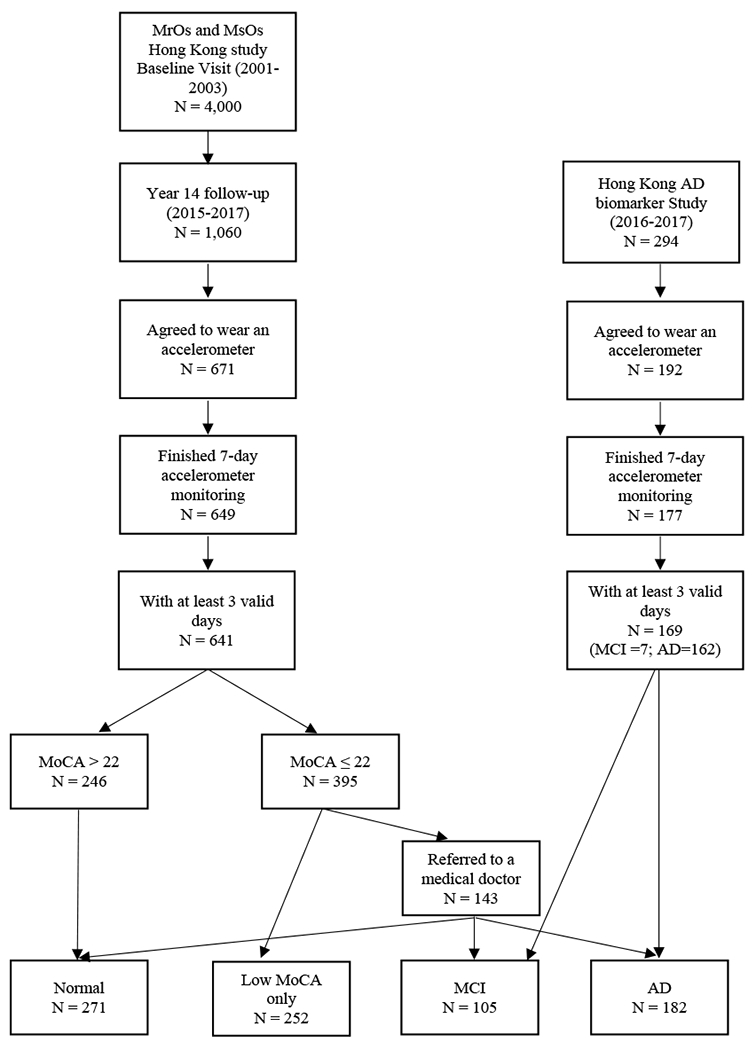

Participants were from two existing studies: the MrOs and MsOs Hong Kong cohort study and the Hong Kong AD biomarker study (ADB) (Figure 1). The MrOs and MsOs study is the first large-scale osteoporosis study in Hong Kong and was initiated in 2001 with 2,000 men and 2,000 women. Detail of the study was well described elsewhere [22]. Between 2015 and 2017, participants were invited for a 14-year follow-up visit that included repeat questionnaire interviews and physical measurements. Of the 4,000 initial study participants, 1,060 returned for the follow-up visit. As part of the follow-up visit, all participants were also asked to wear a wrist-worn accelerometer for 7 days; 671 agreed to wear an accelerometer. Participants who wore an accelerometer were younger, had a larger percentage of men, higher average HK-MoCA score and higher average years of education.

Figure 1.

Participants flow chart.

To supplement the group with poor cognitive function, we also included participants from the ADB study. This study was initiated in March 2016 and recruited Chinese older adults in Hong Kong who were 65 years and older, and had been diagnosed as having either amnestic MCI or early stage of AD in either a Memory Clinic or a Geriatrics Clinic. All diagnoses were adjudicated by at least two experienced physicians based on a comprehensive clinical evaluation and review of medical records. The diagnosis of AD was made based on NINCDS-ADRDA criteria [23]. Registry participants received cognitive testing, physical measurements, volumetric MRI and clinical examinations in the study. During the same period as the MrOs and MsOs study, the ADB study recruited 294 participants and 192 of them agreed to wear an accelerometer for 7 days. There was no significant difference on age, gender, years of education and gait speed between who wore the accelerometer and who did not.

Participants from both studies were included for analysis if they had at least 3 days of valid accelerometer wear (described below). This resulted in a final analysis sample of 810 (641 from MrOs and MsOs and 169 from ADB study). Written informed consent was obtained from each subject and the study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committees of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Cognitive function assessment

Cognitive function was assessed by the validated Hong Kong version of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (HK-MoCA) in both studies [24]. The HK-MoCA assesses various cognitive domains including visuospatial/executive function, attention, language, recall and orientation. The HK-MoCA scale has a maximum score of 30, and one point is added if the person has 6 years of education or less. The cutoff score for the HK-MoCA to differentiate cognitive impaired persons from normal is 21/22. In the MrOs and MsOs study, participants who scored above 22 were classified as being cognitively normal. Participants who scored 22 or below were referred for further diagnosis by a physician. Based on the prior cognitive assessments, demographics, medical history, medications, depression score, and functional status, participants were diagnosed as AD, MCI or cognitively normal. The remaining participants who scored below 22 but refused to see the doctor were classified as being low MoCA only. In the ADB study, participants also underwent the HK-MoCA.

Accelerometer-assessed physical activity

Participants attending the clinic were asked to wear an Actigraph wGT3x-BT accelerometer (Pensacola, Florida, USA) on their non-dominant wrist for 7 consecutive days in free-living environment. Participants were instructed to wear the device at all time, except when bathing or swimming. Compared to hip-worn accelerometers, wrist-worn accelerometers increase participant compliance, enable measurement of sleep duration, and better detect light activity which may be primarily upper body movement [25]. In the MrOs and MsOs study, participants also completed a sleep log, indicating when they went to bed and awakened each day.

Accelerometer data were collected at 100 Hz and aggregated to 60-second epochs for analysis. Because participants from the ADB study did not have sleep logs, we used the ActiGraph algorithm available in the ActiLife software to classify the accelerometer day into in-bed time and waking time to all participants. AtiGraph algorithm was recommended in studies without sleep log information, because its estimations have been proven to be closer to self-reported in-bed time than other algorithms [26]. We have also done a sensitivity analysis among those who have sleep logs in the MrOs and MsOs study, the in-bed time was 465.8 ± 68.6 min/night measured by AtiGraph algorithm and 480.6 ± 70.2 min/night by sleep logs. The interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was 0.93, 95%CI = (0.92, 0.94), which suggested the in-bed time was comparable from sleep logs to this algorithm in our study (supplementary Figure 1 shows a Bland Altman plot). During wake time, accelerometer data were screened for periods of non-wear. Non-wear time during waking hours was identified by the Choi algorithm as more than 90 consecutive minutes of vector magnitude (VM) zero counts, allowing for 2 minutes of non-zero counts, providing that there were 30 minutes of zero counts before or after that interval [27, 28]. A valid wear day consisted of at least 10 waking hours of wear time, and participants with at least 3 valid days were included in analyses. All participants provided an average of 5.8 (range 3 – 7) valid days of accelerometer data.

The triaxial accelerometers measured acceleration on vertical, horizontal and perpendicular axes. VM counts per minute (cpm) is a metric incorporating movement across all three axes of the accelerometer over a minute. Both wake time and sleep time VM cpm were summarized for two sets of analyses: (i) the hour level and (ii) the day level. The hourly VM cpm was used to visually examine the activity patterns throughout a day. The day level measures included daily average VM cpm, percentage of wear-time spent in sedentary behavior and average VM cpm during sleeping hours. All these metrics were calculated per day and averaged over valid days. Sedentary behavior was categorized using the cut-point of less than 1,853 VM cpm, which was validated by using the activPAL as the reference criteria, the most accurate and precise monitor to distinguish postures and assess sedentary behavior [29]. Then, ≥ 1,853 VM cpm would be regarded as non-sedentary behavior. A further summary on patterns of sedentary behaviors included (i) average length of sedentary bouts (defined as a period of consecutive minutes with accelerometer registered < 1,853 VM cpm); (ii) total numbers of sedentary bouts (≥ 1 min); (iii) numbers of long sedentary bouts (≥ 30 min); (iv) numbers of sedentary breaks (defined as a period of 1–3 consecutive min when the accelerometer registered ≥ 1,853 VM cpm); (v) numbers of long non-sedentary bouts (≥ 10 min).

Participant characteristics and health status

Age, gender, years of education, and living status (living alone/with families/with maid/in elderly home) were self-reported via an interview questionnaire. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from measured weight and height (kg/m2). Gait speed was measured by the time to walk 6 meters at usual pace. Participants reported whether they were ever told by a doctor or other health professional that they had any of the following conditions: hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and Parkinson’s disease. We created a variable of disease burden defined as the sum of the number of diseases reported.

Statistical Analyses

Analysis of variance [30] for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables were used to examine the difference in participant characteristics for four cognition groups. The differences in patterns of PA and sedentary behavior for the four groups were examined using the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) adjusted for covariates. Least squares (LS) means and standard errors were estimated in two models to compare the difference of average activity counts during awake time and sleep time, percentage of sedentary time and sleep time for the four groups. Model 1 was adjusted for age, gender and wear time. Model 2 was further adjusted for years of education, BMI, usual gait speed, living status and disease burden. To visualize the patterns of PA during the awake time and in-bed time, we plotted the mean of VM cpm at each hour for each group. Then, to investigate how the activity was different between groups, the LS means of numbers and length of the activity bouts and sedentary bouts were reported and pairwise comparisons were performed across each group using Model 2. All analyses were conducted using the R studio (version 1.1.383). All tests were two-sided and p values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participants’ characteristics by cognition group are showed in Table 1. The average awake wear time of the 810 participants was 951.4 minutes/day, and the mean age was 82.4 (±4.4, range 65 – 96) years. Cognitively normal participants were younger, except the AD group (because we also included AD participants from a specific ADB study). Across cognition groups, the normal group tended to have fewer women; had higher HK-MoCA scores; had more years of education; and walked faster (all p < 0.001). 15.9% of participants in normal group lived alone. Most participants in the AD group lived with their families or maids (84% and 8% respectively), but 1.6% of them lived in the elderly home.

Table 1.

Particiant characteristics by cogntion groups.

| Characteristic | Normal (n = 271) | Low MoCA only (n = 252) | MCI (n = 105) | AD (n = 182) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waking wear time (min/day) | 959.5 ± 74.1 | 945.6 ± 82.5 | 959.3 ± 119.2 | 942.7 ± 88.9 | 0.106 |

| Age (years) | 81.9 ± 3.5 | 83.4 ± 4.0 | 83.6 ± 3.7 | 80.8 ± 5.9 | <0.001 |

| Female | 104 (38.2%) | 120 (47.6%) | 51 (48.6%) | 121 (65.4%) | <0.001 |

| HK-MoCA score | 24.4 ± 2.4 | 19.1 ± 3.1 | 18.1 ± 3 | 13.1 ± 5.1 | <0.001 |

| Years of education | 8.7 ± 4.9 | 6.3 ± 4.8 | 4.5 ± 4.4 | 5.3 ± 4.9 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.7 ± 3.4 | 23.4 ± 3.2 | 23.3 ± 3.3 | 23.4 ± 3.5 | 0.529 |

| Gait speed, m/s | 0.88 ± 0.21 | 0.78 ± 0.21 | 0.77 ± 0.19 | 0.71 ± 0.21 | <0.001 |

| Disease burden | 0.070 | ||||

| 0 | 71 (26.2%) | 64 (25.4%) | 25 (23.8%) | 41 (22.5%) | |

| 1 | 128 (47.2%) | 114 (45.2%) | 47 (44.8%) | 67 (36.8%) | |

| 2+ | 72 (26.6%) | 74 (29.4%) | 33 (31.4%) | 74 (40.7%) | |

| Living status | <0.001 | ||||

| Alone | 43 (15.9%) | 30 (11.9%) | 15 (14.9%) | 12 (6.6%) | |

| With families | 193 (71.2%) | 165 (65.5%) | 81 (77.1%) | 152 (83.5%) | |

| With maids | 35 (12.9%) | 53 (21%) | 9 (8.6%) | 15 (8.2%) | |

| In elderly home | 0 (0%) | 4 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.6%) |

Note: Data are shown as mean ± SD or N (%). MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; AD = Alzheimer’s disease.

p Value of ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables.

Table 2 presents the difference of overall wake time VM cpm, sedentary behavior, total in-bed time and sleep time VM cpm across cognition groups. After adjusting for age, gender and waking wear time, there was no significant difference between participants who were cognitively normal, MCI and low MoCA only. However, AD participants exhibited significantly lower average VM cpm during the day (p < 0.05) and spent a significantly larger proportion of waking wear time in sedentary behavior (p < 0.05) when comparing to all the other 3 groups individually. During the night, there was no significant difference in the in-bed time duration and activity.

Table 2.

Overall characteristics of physical activity, sedentary behavior and sleep by cognition groups.

| Normal (n = 271) | Low MoCA only (n = 252) | MCI (n = 105) | AD (n = 182) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VM cpm during wake time | ||||

| Model 1 | 1953.5 ± 35.4d | 1975.6 ± 36.7d | 2073.2 ± 56.7d | 1592.1 ± 43.9abc |

| Model 2 | 1945.0 ± 34.3d | 1970.5 ± 34.1d | 2030.6 ± 52.9d | 1695.1 ± 43.0abc |

| % of wear time in Sedentary behavior | ||||

| Model 1 | 58.4 ± 0.7d | 57.7 ± 0.7d | 56.2 ± 1.1d | 65.3 ± 0.9abc |

| Model 2 | 58.4 ± 0.7d | 57.8 ± 0.7d | 57.1 ± 1.1d | 63.2 ± 0.8abc |

| In-bed time | ||||

| Model 1 | 466.5 ± 3.2 | 475.1 ± 3.3 | 469.4 ± 5.2 | 469.9 ± 4.0 |

| Model 2 | 467.5 ± 3.4 | 474.3 ± 3.3 | 469.2 ± 5.2 | 471.9 ± 4.2 |

| VM cpm during sleep | ||||

| Model 1 | 223.6 ± 7.6 | 217.6 ± 7.9 | 241.2 ± 12.3 | 244.8 ± 9.4 |

| Model 2 | 221.3 ± 8.0 | 216.9 ± 7.9 | 242.7 ± 12.5 | 246.8 ± 10.0 |

Notes: MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; AD =Alzheimer’s disease.

Model 1: Adjusted for age, gender and wear time.

Model 2: Adjusted for age, gender, wear time, years of education, BMI, usual gait speed, living status and disease burden

p < 0.05 for pairwise mean difference when comparing with normal group.

p < 0.05 for pairwise mean difference when comparing with low MoCA only group.

p < 0.05 for pairwise mean difference when comparing with MCI group.

p < 0.05 for pairwise mean difference when comparing with AD group.

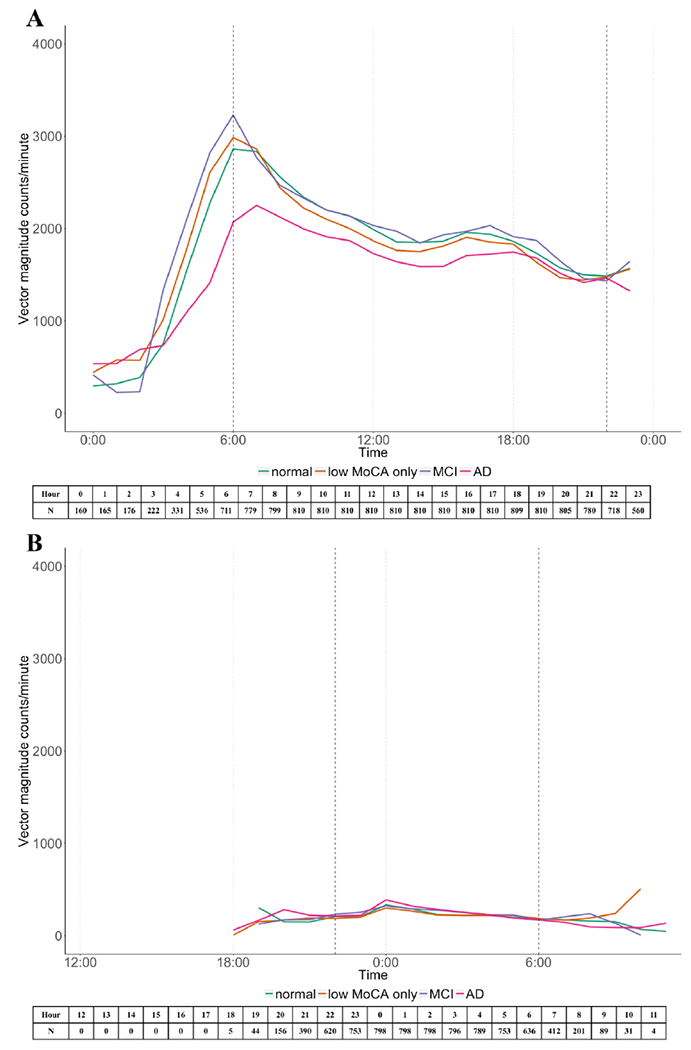

Figure 2 shows the waking time and sleep time activity patterns for each cognition group with plots of mean VM cpm over a 24-hour period. During waking hours, activity in each group peaked in the morning, and then declined gradually with a slight increase in the afternoon (Figure 2-A). The curves overlapped for the three non-AD groups. However, there was a distinct difference between AD participants and the others. AD participants usually initiated their activity progressively later in the morning. Their activity peak was not as steep as the others and their activity never reached the level of other three groups throughout the day. During the night, the patterns of the activity were similar across groups. There was increasing variability at the beginning and the end of the day which may reflect fewer registered accelerometer data (Figure 2-B).

Figure 2.

24-hour awaking time (A) and in-bed time (B) average vector magnitude counts per minutes for each cognitive group. The number of people who had registered accelerometer data in each hour was listed below each figure.

Table 3 further compared the patterns of sedentary bouts across cognition groups. The three non-AD groups, again, showed no significant difference when compared with each other. On average, the sedentary bout length for AD participants was 7.9 minutes, which was significantly longer than the others three groups (p < 0.05). Compared to the others, participants with AD had fewer total numbers of sedentary bouts (p < 0.05), but they had more sedentary bouts over 30 minutes (p < 0.05). All participants had similar numbers of non-sedentary bouts lasting for 1 to 3 minutes. However, participants with AD had significantly fewer numbers of non-sedentary bouts lasting over 10 minutes (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Patterns of sedentary behavior by cognition groups.

| Normal (n = 271) | Low MoCA only (n = 252) | MCI (n = 105) | AD (n = 182) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average sedentary bout length | 6.6 ± 0.2d | 6.5 ± 0.2d | 6.3 ± 0.3d | 7.9 ± 0.2abc |

| Numbers of sedentary bouts (≥ 1 min) | 91.5 ± 1.0d | 91.4 ± 1.0d | 89.4 ± 1.6 | 86.1 ± 1.3ab |

| Numbers of sedentary bouts (≥ 30 min) | 3.3 ± 0.1d | 3.3 ± 0.1d | 3.5 ± 0.2d | 4.1 ± 0.1abc |

| Numbers of non-sedentary bouts (1–3 min) | 60.9 ± 0.8 | 60.5 ± 0.8 | 58.1 ±1.3 | 59.3 ± 1.1 |

| Numbers of non-sedentary bouts (≥ 10 min) | 10.0 ± 0.3d | 10.2 ± 0.3d | 10.6 ± 0.4d | 8.5 ± 0.3abc |

Notes: MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; AD = Alzheimer’s disease.

Least square means are adjusted for age, gender, years of education, BMI, usual gait speed, living status, disease burden and wear time.

p < 0.05 for pairwise mean difference when comparing with normal group.

p < 0.05 for pairwise mean difference when comparing with low MoCA only group.

p < 0.05 for pairwise mean difference when comparing with MCI group.

p < 0.05 for pairwise mean difference when comparing with AD group.

DISCUSSION

In this study of 810 free-living older adults in Hong Kong, we found no significant differences of daily PA and sedentary behaviors between cognitively normal and MCI participants. However, compared to the non-AD participants, participants with AD were less active particularly in the morning, and were more sedentary throughout the waking hours in the day independent of all covariates. We further found that participants with AD did not have more numbers of sedentary bouts than the others, but they did have more sedentary bouts for longer duration as well as fewer numbers of long-lasting non-sedentary bouts. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive study to provide detailed profiles on how daily PA and sedentary behavior were patterned for individuals in different cognitive status for older Asian population. The differences in patterns suggested that cognitive status may alter the purpose and type of PA intervention for older adults with AD.

Interestingly, participants with MCI did not differ from their cognitively healthy peers in patterns of PA and sedentary behavior. There are several potential explanations for our findings. A recent study showed that people with probable MCI engaged in fewer amounts of moderate-to-vigorous PA than participants without MCI [31]. This may suggest that individuals with MCI may engage in similar amounts of total activity to their cognitively healthy peers, but do not engage in as much moderate-to-vigorous activity. Further explore on PA at this intensity is needed for our population. Increasing evidence has also demonstrated that PA has a bidirectional relationship with executive function, which is used to define planning and problem-solving [32, 33]. It is therefore possible that because people with MCI were physically active, they maintained their independence and good executive function, which in turn influenced their decision to engage in PA. Declining physical activity may partly be attribute to ongoing pathologic progress which leads to subsequent dementia [34]. Thus, the onset of PA decline for individuals with MCI may be a potential signal of transitioning to AD. Early detection of decline of PA in such persons is essential, because individuals at risk for further declines in PA may benefit substantially from intervention efforts.

PA patterns during waking hours showed that all participants were most active in the morning and then activity decreased through the day. Our findings are consistent with previous evidence [35–37], but activity peaked even earlier for our non-AD participants (at around 6 am). The most striking difference of patterns between AD participants with the others was the amplitude and the timing of peak activity during the morning. Prior study has demonstrated that individual with mild AD participated in less moderate-intensity PA particularly in the morning, because many moderate physical activities may be more challenging for individuals with mild AD for being more physically demanding and cognitively complex [21]. Therefore, instead of using the same strategies for all older adults, it may be more appropriate to design tailored activity intervention with consideration for specific times during the day for individuals with AD.

Sleep may also play a role in the relationship between physical activity and cognitive function. We observed that AD participants did not have significant different in-bed time from non-AD participants, but they tended to accrue activity later in the morning. This may lead to delays in sleep onset or alternations in the sleep/wake pattern for AD participants. Accumulating evidence suggests individuals with AD may experience sleep disruption and circadian dysregulation, which might promote AD pathogenesis [38]. A longitudinal study observed that older women with decreased circadian activity rhythm amplitude and delayed rhythms had greater risks of developing MCI and dementia [39]. These changes may also impact the pattern of physical activity over the course of wake time. Future study to explore the association between changes of circadian rhythm with physical activity is needed.

Being less active for AD participants may also be due to having fewer numbers of activity bouts and spending more time in sedentary behaviors. Firstly, participants with AD had fewer non-sedentary bouts over 10 minutes, which implied that they were unlikely to be active for longer duration, regardless of the activity intensity. Moreover, participants with AD spent larger proportion of time in sedentary behaviors than their non-AD counterparts, which was consistent with other studies [18, 20]. However, the reason why participants with AD were more sedentary might be because of having excessive sedentary bouts lasting over 30 minutes, rather than having greater numbers of total sedentary bouts. Given that they did not have sufficient sedentary breaks since they had similar numbers of shorter activity bouts (1 to 3 minutes) to other non-AD participants, it could be more effective to interrupt long sedentary bouts by short bouts of PA or standing for AD individuals [40], and then gradually promote their activity.

The study has several potential limitations. Using the ActiGraph Algorithm for sleep detection may not be as good as using the sleep log, but the estimation from this algorithm had a high accuracy to sleep log. We were unable to characterize the activity intensity because there are currently no validated cut-points for the Actigraph wGT3x-BT wrist-worn accelerometers. Activities during swimming would not be captured because participants were instructed to remove the Actigraph in this period. But when we excluded the 25 people who had reported swimming in their logs, the results did not change significantly (results were not shown). As a large proportion of participants did not have a further diagnosis by a physician, that might have misclassified normal cognition and MCI. In addition, the small sample size of the MCI group may limit the power to detect significance in pairwise comparisons. The cross-sectional design limits the ability to determine the casual relationship between cognitive function and PA and future longitudinal studies are warranted.

This study benefits from using a large sample of Hong Kong Chinese older adults from the MrOs and MsOs cohort study and the ADB study. Participants with MCI and AD were diagnosed by physicians. The low MoCA only group enables the comparison to other studies where cognitive impairment was only assessed by cognitive tests. All participants wore an accelerometer for 3 or more days in the free-living environment and the 24-hour data offered insight into the patterns of PA for each cognition groups.

In conclusion, our findings from the distinctive patterns of PA and sedentary behavior for individuals with MCI and AD supported the idea to design and implement tailored intervention to reduce their prolonged sedentary duration and encourage more PA. More detail information on sleep pattern is warranted and further work is also needed to understand the association between physical activity and the progression of MCI.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Bland Altman plot for in-bed time by log and by Actigraph Algorithm.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- [1].Fiest KM, Jette N, Roberts JI, Maxwell CJ, Smith EE, Black SE, Blaikie L, Cohen A, Day L, Holroyd-Leduc J, Kirk A, Pearson D, Pringsheim T, Venegas-Torres A, Hogan DB (2016) The Prevalence and Incidence of Dementia: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Can J Neurol Sci 43 Suppl 1, S3–s50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Winblad B, Amouyel P, Andrieu S, Ballard C, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Cedazo-Minguez A, Dubois B, Edvardsson D, Feldman H, Fratiglioni L, Frisoni GB, Gauthier S, Georges J, Graff C, Iqbal K, Jessen F, Johansson G, Jonsson L, Kivipelto M, Knapp M, Mangialasche F, Melis R, Nordberg A, Rikkert MO, Qiu C, Sakmar TP, Scheltens P, Schneider LS, Sperling R, Tjernberg LO, Waldemar G, Wimo A, Zetterberg H (2016) Defeating Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: a priority for European science and society. Lancet Neurol 15, 455–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rabins PV, Ritchie K, Rossor M, Thal L, Winblad B (2001) Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 58, 1985–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Canevelli M, Grande G, Lacorte E, Quarchioni E, Cesari M, Mariani C, Bruno G, Vanacore N (2016) Spontaneous Reversion of Mild Cognitive Impairment to Normal Cognition: A Systematic Review of Literature and Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 17, 943–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Brayne C (2014) Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol 13, 788–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gallaway PJ, Miyake H, Buchowski MS, Shimada M, Yoshitake Y, Kim AS, Hongu N (2017) Physical Activity: A Viable Way to Reduce the Risks of Mild Cognitive Impairment, Alzheimer’s Disease, and Vascular Dementia in Older Adults. Brain Sci 7, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Blondell SJ, Hammersley-Mather R, Veerman JL (2014) Does physical activity prevent cognitive decline and dementia?: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health 14, 510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hamer M, Chida Y (2009) Physical activity and risk of neurodegenerative disease: a systematic review of prospective evidence. Psychol Med 39, 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sofi F, Valecchi D, Bacci D, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A, Macchi C (2011) Physical activity and risk of cognitive decline: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Intern Med 269, 107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Stephen R, Hongisto K, Solomon A, Lonnroos E (2017) Physical Activity and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 72, 733–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fiatarone Singh MA, Gates N, Saigal N, Wilson GC, Meiklejohn J, Brodaty H, Wen W, Singh N, Baune BT, Suo C, Baker MK, Foroughi N, Wang Y, Sachdev PS, Valenzuela M (2014) The Study of Mental and Resistance Training (SMART) study-resistance training and/or cognitive training in mild cognitive impairment: a randomized, double-blind, double-sham controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 15, 873–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Panza GA, Taylor BA, MacDonald HV, Johnson BT, Zaleski AL, Livingston J, Thompson PD, Pescatello LS (2018) Can Exercise Improve Cognitive Symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease? A Meta-Analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 66, 487–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Falck RS, Davis JC, Liu-Ambrose T (2017) What is the association between sedentary behaviour and cognitive function? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 51, 800–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].(2012) Letter to the editor: standardized use of the terms “sedentary” and “sedentary behaviours”. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 37, 540–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Schrack JA, Cooper R, Koster A, Shiroma EJ, Murabito JM, Rejeski WJ, Ferrucci L, Harris TB (2016) Assessing Daily Physical Activity in Older Adults: Unraveling the Complexity of Monitors, Measures, and Methods. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 71, 1039–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].James BD, Boyle PA, Bennett DA, Buchman AS (2012) Total Daily Activity Measured With Actigraphy and Motor Function in Community-Dwelling Older Persons With and Without Dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 26, 238–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kuhlmei A, Walther B, Becker T, Muller U, Nikolaus T (2013) Actigraphic daytime activity is reduced in patients with cognitive impairment and apathy. Eur Psychiatry 28, 94–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Marmeleira J, Ferreira S, Raimundo A (2017) Physical activity and physical fitness of nursing home residents with cognitive impairment: A pilot study. Exp Gerontol 100, 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Moyle W, Jones C, Murfield J, Draper B, Beattie E, Shum D, Thalib L, O’Dwyer S, Mervin CM (2017) Levels of physical activity and sleep patterns among older people with dementia living in long-term care facilities: A 24-h snapshot. Maturitas 102, 62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].van Alphen HJ, Volkers KM, Blankevoort CG, Scherder EJ, Hortobagyi T, van Heuvelen MJ (2016) Older Adults with Dementia Are Sedentary for Most of the Day. PLoS One 11, e0152457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Varma VR, Watts A (2017) Daily Physical Activity Patterns During the Early Stage of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 55, 659–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lau EM, Leung PC, Kwok T, Woo J, Lynn H, Orwoll E, Cummings S, Cauley J (2006) The determinants of bone mineral density in Chinese men--results from Mr. Os (Hong Kong), the first cohort study on osteoporosis in Asian men. Osteoporos Int 17, 297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM (1984) Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 34, 939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yeung PY, Wong LL, Chan CC, Leung JL, Yung CY (2014) A validation study of the Hong Kong version of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (HK-MoCA) in Chinese older adults in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 20, 504–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Quante M, Kaplan ER, Rueschman M, Cailler M, Buxton OM, Redline S (2015) Practical considerations in using accelerometers to assess physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep. Sleep Health 1, 275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Pulakka A, Shiroma EJ, Harris TB, Pentti J, Vahtera J, Stenholm S (2018) Classification and Processing of 24-Hour Wrist Accelerometer Data. Jornal for the Measurement of Physical Behaviour 1, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Choi L, Liu Z, Matthews CE, Buchowski MS (2011) Validation of accelerometer wear and nonwear time classification algorithm. Med Sci Sports Exerc 43, 357–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Choi L, Ward SC, Schnelle JF, Buchowski MS (2012) Assessment of wear/nonwear time classification algorithms for triaxial accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc 44, 2009–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Koster A, Shiroma EJ, Caserotti P, Matthews CE, Chen KY, Glynn NW, Harris TB (2016) Comparison of Sedentary Estimates between activPAL and Hip- and Wrist-Worn ActiGraph. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48, 1514–1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Casanova C, Hernandez MC, Sanchez A, Garcia-Talavera I, de Torres JP, Abreu J, Valencia JM, Aguirre-Jaime A, Celli BR (2006) Twenty-four-hour ambulatory oximetry monitoring in COPD patients with moderate hypoxemia. Respir Care 51, 1416–1423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Falck RS, Landry GJ, Best JR, Davis JC, Chiu BK, Liu-Ambrose T (2017) Cross-Sectional Relationships of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior With Cognitive Function in Older Adults With Probable Mild Cognitive Impairment. Phys Ther 97, 975–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Allan JL, McMinn D, Daly M (2016) A Bidirectional Relationship between Executive Function and Health Behavior: Evidence, Implications, and Future Directions. Front Neurosci 10, 386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Daly M, McMinn D, Allan JL (2014) A bidirectional relationship between physical activity and executive function in older adults. Front Hum Neurosci 8, 1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Tolppanen AM, Solomon A, Kulmala J, Kareholt I, Ngandu T, Rusanen M, Laatikainen T, Soininen H, Kivipelto M (2015) Leisure-time physical activity from mid- to late life, body mass index, and risk of dementia. Alzheimers Dement 11, 434–443.e436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Martin KR, Koster A, Murphy RA, Van Domelen DR, Hung MY, Brychta RJ, Chen KY, Harris TB (2014) Changes in daily activity patterns with age in U.S. men and women: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–04 and 2005–06. J Am Geriatr Soc 62, 1263–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sartini C, Wannamethee SG, Iliffe S, Morris RW, Ash S, Lennon L, Whincup PH, Jefferis BJ (2015) Diurnal patterns of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behaviour in older men. BMC Public Health 15, 609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Schrack JA, Zipunnikov V, Goldsmith J, Bai J, Simonsick EM, Crainiceanu C, Ferrucci L (2014) Assessing the “physical cliff”: detailed quantification of age-related differences in daily patterns of physical activity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 69, 973–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Landry GJ, Liu-Ambrose T (2014) Buying time: a rationale for examining the use of circadian rhythm and sleep interventions to delay progression of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci 6, 325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tranah GJ, Blackwell T, Stone KL, Ancoli-Israel S, Paudel ML, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Redline S, Hillier TA, Cummings SR, Yaffe K (2011) Circadian activity rhythms and risk of incident dementia and MCI in older women. Ann Neurol 70, 722–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, Nieman DC, Swain DP (2011) American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 43, 1334–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Bland Altman plot for in-bed time by log and by Actigraph Algorithm.