Abstract

Objectives:

Awareness and acceptance of transgenderism have increased in the last two decades. There is limited literature regarding the incidence and semen characteristics of transwomen banking sperm. We sought to assess the incidence of sperm cryopreservation of transgender individuals compared to the cisgender population in the last 10 years. Semen parameters were also compared between the two groups.

Materials and Methods:

We performed a retrospective analysis of sperm cryopreservation performed at a single center from 2006 through 2016. Using available data on indications for banking and prior hormonal therapy status, we isolated healthy transgender and cisgender cohorts for semen parameter comparison. Linear regression was used to compare the incidence trends. Semen parameters were compared using the generalized estimating equations method. The rates of semen parameter abnormality of each group were compared using Chi-square test. Semen parameter abnormalities were defined using WHO 2010 reference values.

Results:

We analyzed 194 transgender samples and 2327 cisgender samples for a total of 84 unique transgender sperm bankers and 1398 unique cisgender sperm bankers. The number of transgender sperm bankers increased relative to cisgender sperm bankers from 2006 to 2016. Following exclusion of cisgender sperm bankers with health issues that might impact semen quality and transgender sperm bankers with known prior hormonal therapy, we compared the semen parameters of 141 healthy cisgender sperm bankers and 78 healthy transgender sperm bankers. The transgender sperm bankers demonstrated lower sperm concentration, total motile sperm count, and post-thaw sperm parameters. The transgender sperm bankers also demonstrated a higher incidence of oligozoospermia.

Conclusions:

This is the largest report to date on the incidence of transgender sperm cryopreservation and comparison of semen characteristics with cisgender sperm bankers. The data reveal an increased incidence of transgender sperm banking as well as poorer semen parameters of transgender individuals compared to cisgender controls.

Keywords: transgender, gender dysphoria, cryopreservation, sperm banking

Introduction:

Male-to-female transgenderism denotes a condition in which one’s natal sex assignment is male, but the individual identifies as female (as opposed to cisgender in which one’s gender identity corresponds to the natal sex). The prevalence of transgenderism is difficult to ascertain due to lack of formal studies; current studies are riddled with limitations such as cultural barriers and under-reporting (Zucker & Lawrence, 2009). Review of the literature published in the last several decades, mainly from European countries (Walinder, 1971; Weitze & Osburg, 1996) reveals prevalence ranges from 1:11,900 to 1:45,000 for male-to-female individuals (transwomen) and 1:30,400 to 1:200,000 for female-to-male individuals (transmen) (Decuypere et al., 2007). However, data from these studies only account for individuals who present to health care clinics for treatment. Therefore, these numbers only reflect individuals who seek medical assistance and those with access to health clinics (Coleman et al., 2011). A more recent study based on survey data in the United States estimates the prevalence of transgenderism at 0.6%, which is much higher than prior studies (Flores et al., 2016).

A variety of therapeutic options for transwomen with gender dysphoria is available. These include changes in gender expression and role, psychiatric counseling for co-existing conditions, hormonal therapy, and surgery. The latter two options convey significant implications on future fertility. De Sutter et al surveyed 121 transwomen regarding sperm cryopreservation, the majority of whom responded that it should be discussed and offered by healthcare providers (De Sutter et al., 2002).

In this study, we sought to assess the incidence of transwomen seeking sperm cryopreservation compared to cismen in the last 10 years at a commercial sperm bank. We also compared semen parameters between the two populations. We hypothesized that there would be an increasing incidence of transgender sperm cryopreservation over the last 10 years, corresponding to increasing awareness, and that there are no differences between transgender and cisgender sperm bankers’ semen parameters.

Materials and Methods:

Deidentified sperm cryopreservation patient data were obtained retrospectively from New England Cryogenic Center for the years 2006 through 2016 following Institutional Review Board approval. Patients self-identified as cisgender or transgender. Patients who preserved multiple semen samples had the collective semen parameters averaged and the means used for statistical analysis. Linear regression analysis was used to compare the annual incidence trend of sperm cryopreservation from 2006-2016 of cismen versus transwomen.

All patients were instructed to abstain from sexual activity for 3 days before sample collection. Fresh ejaculate was allowed to liquefy in a 37°C incubator for 20 minutes before manual semen analysis. An equal volume of either TEST-yolk buffer (Irvine Scientific, Irvine, CA) or Sperm Maintenance Medium (Irvine Scientific, Irvine, CA), was added dropwise to each specimen. All specimens were cryopreserved in sterile plastic cryovials in liquid nitrogen vapor followed by plunging and storage in the liquid phase. A post-thaw test vial was held at room temperature for 7 minutes and then incubated at 37° C for 14-15 minutes before post-thaw analysis.

We examined the indications for sperm cryopreservation for all sperm bankers. Among the cismen with known indications, individuals with malignancy (solid and blood-borne cancers) or systemic illness (e.g., autoimmune disorders, renal or liver illness, amyloidosis) were excluded, as well as those with a high likelihood of abnormal semen parameters (e.g., infertility). The only indications included in the healthy cisgender group were pre-vasectomy, military deployment, personal reasons, travel, and occupational hazard. This resulted in a healthy cisgender cohort of 141 individuals. Six transwomen who started hormonal therapy prior to sperm banking were excluded, resulting in a healthy transgender cohort of 78 individuals. We compared the semen parameters of these two populations, henceforth referred to as “healthy cismen” and “healthy transwomen”

Mean age and days of abstinence between the healthy cismen and healthy transwomen populations were compared using Student’s t-test. We then applied generalized estimating equations (GEE) method to compare semen parameters between the two cohorts (Zeger et al., 1989). The GEE accounts for variability in the number of sperm samples banked per individual. Extreme values were observed (confirmed with Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for non-normality), thus we chose to rank the data before conducting the statistical tests. Because of non-normal distribution of semen parameter data, results (volume, sperm concentration, sperm count, % sperm motility, total motile sperm count (TMSC), post-thaw sperm count, post-thaw motility, and post-thaw TMSC) are reported using median and inter-quartile range.

The rates of semen parameter abnormalities of each group were compared using the Chi-square test. Semen parameter abnormalities were defined using 2010 WHO reference values for semen characteristics (Cooper et al., 2010). Specifically, low semen volume was defined as <1.5mL per ejaculate, oligozoospermia was defined as <15 million sperm per mL, and asthenozoospermia was defined as <40% motile sperm.

Finally, we performed a cryosensitivity analysis for post-thaw semen parameters (sperm count, motility, TMSC). A cryosensitivity index for each post-thaw semen parameter was calculated by dividing the post-thaw parameter by the corresponding pre-freeze parameter. For example, the cryosensitivity index for sperm count = post-thaw sperm count/pre-freeze sperm count. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the medians and spread of the calculated cryosensitivity indices between healthy cismen and healthy transwomen. All statistical tests were two-sided. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Statistical Package Ver. 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results:

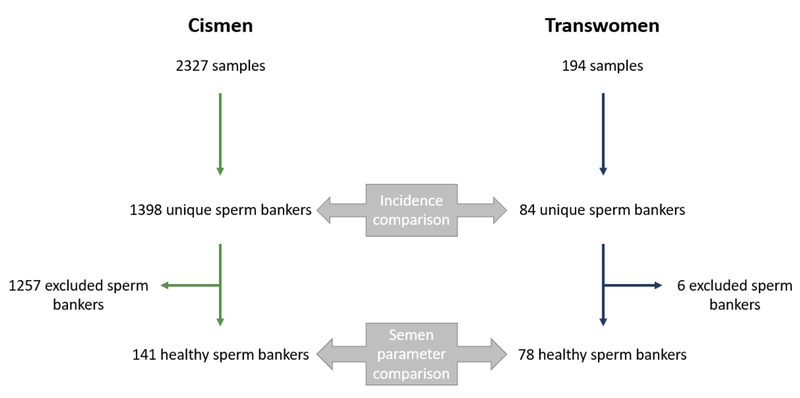

We analyzed 2327 cisgender samples and 194 transgender samples for a total of 1398 unique cismen sperm bankers and 84 unique transwomen sperm bankers. Among the 1398 cismen sperm bankers, 1257 were excluded due to either unknown indications or known indications (e.g., cancer) which could impact semen parameters. Among the 84 transwomen, 6 were excluded due to initiation of hormonal therapy prior to sperm banking (Figure 1). The duration of therapy prior to sperm banking was unknown.

Fig 1.

Flowchart of cismen and transwomen cohorts used for incidence and semen parameter comparisons.

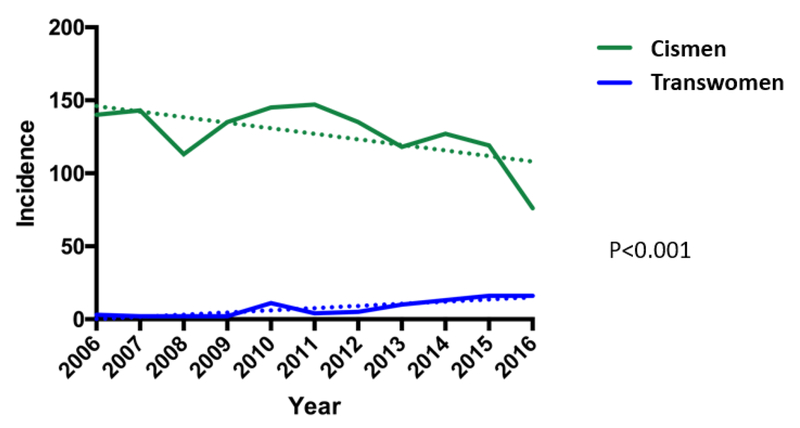

The number of transwomen pursuing sperm cryopreservation increased relative to cismen from 2006 to 2016. The annual percent change of the two groups was significantly different – (−)5.93% for cismen vs (+)18.22% for transwomen (Figure 2). There is a downward trend of cismen sperm banking over time as opposed to transwomen sperm banking which demonstrated an upward trend.

Figure 2.

Incidence trends of unique cismen and transwomen pursuing sperm cryopreservation from 2006-2016

The indication for transwomen sperm cryopreservation was uniformly in preparation for gender affirming treatment. In contrast, the indications for cismen sperm cryopreservation were highly varied (Table 1). Of note, 31.8% of cismen had unknown indications for sperm banking and were not included in the data presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Indication frequencies for cis bankers (N = 954)

| Indication for banking | Frequency percentage |

|---|---|

| Non-genitourinary solid organ cancer | 22.1% |

| Testicular cancer | 20.1% |

| Leukemia/Lymphoma | 14.6% |

| Infertility/IVF | 10.7% |

| Prostate cancer | 9.9% |

| Pre-vasectomy | 6.9% |

| Advanced age | 3.2% |

| Autoimmune disorder | 2.8% |

| History of surgery | 2.6% |

| Military deployment | 1.9% |

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | 1.4% |

| Medication effect | 0.8% |

| Post vasectomy | 0.7% |

| Just in case | 0.6% |

| Travel | 0.6% |

| Renal failure | 0.4% |

| Hepatitis | 0.3% |

| Other genetic disorders | 0.1% |

| Kallman syndrome | 0.1% |

| Amyloidosis | 0.1% |

| Occupational hazard | 0.1% |

| Klinefelters syndrome | 0.1% |

| ALS | 0.1% |

The healthy cismen were significantly older than the healthy transwomen – 36.0 vs 24.1 years (Table 2). The days of abstinence were similar. Comparing the semen parameters between the healthy cismen and healthy transwomen, the transwomen demonstrated lower median sperm concentrations (14.2 vs 19.2 × 106/mL), sperm count (55.7 vs 69.5 × 106), TMSC (35.0 vs 42.0 × 106), post-thaw sperm count (27.0 vs 37.0 × 106), post-thaw motility (25.5 vs 33.3 %), and post-thaw TMSC (6.6 vs 11.9 × 106) (Table 2). Furthermore, there was a higher rate of oligozoospermia in the transwomen – 53.8 vs 38.3 % (Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of demographics and sperm parameters in healthy cismen and transwomen

| Healthy cismen | Healthy transwomen | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Demographics | Mean (Standard Deviation) | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 36.0 ± 9.4 | 24.1 ± 7.6 | <0.01 |

| Days of abstinence | 4.3 ± 3.0 | 5.9 ± 10.5 | 0.20 |

| Sperm parameter | Median (Interquartile Range) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ejaculatory Volume (mL) | 3.5 (2.5 - 5.0) | 3.6 (2.5 - 5.0) | 0.80 |

| Sperm Concentration (×106/mL) | 19.2 (6.7 - 39.1) | 14.2 (7.1 – 24.9) | 0.03 |

| Sperm Count (×106) | 69.5 (41.8 - 96.8) | 55.7 (28.5 – 81.3) | <0.01 |

| Sperm Motility (%) | 64.0 (54.0 – 73.0) | 61.7 (50.0 – 70.0) | 0.21 |

| Total Motile Sperm Count (×106) | 42.0 (25.9 - 65.0) | 35.0 (15.0 – 52.4) | 0.01 |

| Post-thaw Sperm Count (×106) | 37.0 (22.4 – 58.3) | 27.0 (13.9 – 45.4) | 0.04 |

| Post-thaw Motility (%) | 33.3 (22.0 – 43.2) | 25.5 (15.1 – 38.5) | 0.04 |

| Post-thaw Total Motile Sperm Count (×106) | 11.9 (5.2 – 22.1) | 6.6 (2.1 – 17.3) | 0.01 |

Table 3.

Frequency of semen abnormalities in healthy cismen and transwomen

| Semen Abnormality | Healthy cismen | Healthy transwomen | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Volume | 8/141 (8.6%) | 6/78 (7.7%) | 0.38 |

| Oligozoospermia | 54/141 (38.3%) | 42/78 (53.8%) | 0.02 |

| Asthenozoospermia | 12/141 (8.5%) | 6/78 (7.7%) | 0.55 |

The healthy transwomen demonstrated increased cryosensitivity to a freeze-thaw cycle by a significant decrease in post-thaw motility as compared to healthy cismen (0.42 vs 0.54 cryosensitivity index) (Table 4). There were no significant differences in cryosensitivity indices regarding total sperm count and total motile sperm count

Table 4.

Comparison of cryosensitivity indices between healthy cismen and transwomen

| Healthy cismen | Healthy transwomen | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Semen parameter | Median (Interquartile Range) | p-value | |

| Sperm Count | 0.49 (0.43 – 0.58) | 0.53 (0.43 – 0.63) | 0.24 |

| Motility | 0.54 (0.35 – 0.62) | 0.42 (0.29 – 0.60) | 0.04 |

| Total Motile Sperm Count | 0.28 (0.17 – 0.36) | 0.25 (0.14 – 0.33) | 0.14 |

Discussion:

The care of transgender individuals is an increasingly important health topic for the medical community. The growing societal awareness requires healthcare providers to be cognizant of burgeoning reproductive counseling and needs for this patient population, unique from their cisgender counterparts. There has been significant debate regarding the ethics of assisted reproduction for transgender individuals (Jones, 2000; De Sutter, 2003). In 2001, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health issued a consensus statement regarding the need to discuss reproductive issues before hormonal treatment (Meyer et al., 2002). The fact that most transmen and transwomen are of reproductive age during their time of transition further underscores the importance of these discussions (Kruekels et al., 2012; T’Sjoen et al., 2013). The question of whether transgender individuals are fit to be parents has been rebuked, as all available studies indicate no difference in cross-gender behavior in the children of transgender parents (Green, 1978; Green, 1998; Freedman et al., 2002). Thus, in recent years the conversation has evolved from an ethical debate of whether to assist, to a practical dialogue of how to assist transgender individuals preserve options for future family building (De Sutter, 2001). Gender dysphoria can present early in these patients -- during adolescence or earlier -- which can make discussions of gender affirmation and future reproductive potential very difficult. While it is beyond the scope of this report to delve into the ethical and legal dilemmas of adolescent sperm cryopreservation, it is clear that all transwomen should be counseled on sperm cryopreservation prior to gender affirming treatment.

In this study, we demonstrated an increased incidence sperm cryopreservation by transwomen compared to cismen over the past decade. We unexpectedly found a decline in the number of cismen submitting samples for sperm cryopreservation. Although we cannot explain this trend, it is interesting to note the upward trajectory of the sperm cryopreservation by transwomen. Understanding the limitation that our study examined only specimens at one cryobank, this observation mirrors recent data on demonstrating an increasing prevalence of transgenderism (Flores et al., 2016) and increasing awareness of transgender healthcare needs in the medical field (Kreukels et al., 2012). Both factors contribute to the increased incidence of transwomen sperm banking.

The indication for sperm cryopreservation for transwomen was homogenous – gender dysphoria with the intent of gender affirmation either with hormonal therapy or surgery. Six transwomen in the cohort started hormonal therapy before providing semen specimens for cryopreservation and were eliminated from data analysis. Detailed information on the duration of hormonal therapy prior to sperm banking was not available. The negative effects of hormonal therapy on spermatogenesis have been well described in the literature (Sapino et al., 1978). Given the known deleterious effect on spermatogenesis, we excluded these individuals from semen parameter analysis to only compare healthy cohorts.

All cismen with unknown indications for sperm banking were excluded from the data analysis in order to eliminate possible negative effects of any medical indication for sperm banking on the semen parameters. Those cismen with any form of malignancy, systemic illness, or organ failure were excluded from the “healthy” cohort. Other reported indications for sperm banking were less clear, such as genetic disorders, autoimmune disorders, and history of surgery. Certainly, not all patients with these disorders have perturbations in their semen parameters. Stricter inclusion criteria were employed in attempt for the healthy cohort to represent the general population as closely as possible

We found statistically significant poorer semen parameters for the healthy transwomen compared to healthy cismen group for most semen parameters; the only semen parameters not statistically different were ejaculatory volume and percent motility. There was an increased frequency of oligozoospermia in the healthy transwomen cohort. Sperm count and motility were worse following freeze-thaw cycle in both groups, which was expected. Critser et al. demonstrated apoptosis and motility loss in up to 50–75% of frozen-thawed spermatozoa (Critser et al., 1988). A more recent study has demonstrated a decrease in TMSC by 32% (Mackenna et al., 2017). Interestingly, the cryosensitivity of motility was significantly higher in the healthy transwomen specimens. The reasons for this finding remains unclear.

To date, there is only one study in the literature examining semen characteristics of transwomen (Hamada et al., 2014). Hamada et al. examined semen analyses of 29 transwomen and found high rates of oligozoospermia, asthenozoospermia, and teratozoospermia. This study was limited by a small sample size, no data regarding pre-banking hormonal therapy, and lack of a cisgender control group for comparison. Like Hamada’s group, we also found higher rates of asthenozoospermia in transwomen, but no differences in rates of oligozoospermia. Morphology was not assessed in our cohort. Despite our initial hypothesis, our data support Hamada and colleagues’ conclusion that transgender patients have abnormal semen parameters.

Based on our current understanding of transwomen, there is no inherent explanation as to why these patients should have decreased sperm concentration, TMSC, and post-thaw motility. The transwomen sperm bankers were significantly younger than the cismen sperm bankers, but the majority were adults, so we expected normal semen parameters (Centola et al., 2016). This may point to unreported hormonal therapy or some inherent physiologic issues with spermatogenesis in transwomen which has yet to be elucidated. Nevertheless, these data should not discourage physicians from counseling their transgender patients regarding sperm cryopreservation.

The present study has several limitations. First, the data were collected from a single private cryobank obtained in a retrospective fashion. Nonetheless, the increasing incidence of transwomen bankers mirrors increases in the transgender population and our data is in agreement with the one previously published analysis. Second, we defined “healthy” cohorts using only indications and prior hormonal therapy data. This resulted in the exclusion of a large proportion of cismen sperm bankers and relatively few transwomen sperm bankers. The degree to which our healthy controls compare to the general healthy population remain unknown. Third, we assumed that the transwomen reported prior hormonal therapy honestly. There may be personal reasons for transwomen not to report prior hormonal therapy use (e.g., concerns that their sample might be rejected or illicit hormonal use). The negative effects of hormonal use on sperm quality are well known; however, the degree to which our findings may be influenced by this is unknown. Finally, there were limited demographic data available. Other factors, such as race, socioeconomic status and access to health insurance could influence the rate of sperm cryopreservation among both cismen and transwomen.

Conclusions:

This study is the largest report of incidence of sperm banking and semen quality among transwomen compared to cismen to date. Paralleling the increasing prevalence and medical awareness of transgenderism, we demonstrate an increasing incidence of sperm cryopreservation by transwomen. We identified poorer semen parameters and increased cryosensitivity of motility in transwomen compared to cismen. Although this study is not without limitations, it adds valuable data to the growing body of literature on transgender fertility preservation and, more importantly, awareness of the need for reproductive counseling and further research in this field.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to acknowledge Amy Blanchard, BS, for assistance with preparing the database.

This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst, The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL1 TR001102) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Centola GM, Blanchard A, Demick J, Li S, Eisenberg ML (2016). Decline in sperm count and motility in young adult men from 2003 to 2013: observations from a U.S. sperm bank. Andrology 4(2), 270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E, Bocktin W, Botzer M, Cohen-Kettenis P, Decuypere G, Feldman J, et al. et Zucker K (2011). Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7. Int. J. Transgenderism 13(4), 165–232. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper TG, Noonan E, von Eckardstein S, Auger J, Baker HW, Behre HM, Haugen TB, Kruger T, Wang C, Mbizvo MT, Vogelson KM (2010). World Health Organization reference values for human semen characteristics. Hum. Reprod 16(3), 231–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critser JK, Huse-Benda AR, Aaker DV, Arneson BW, Ball GD (1988). Cryopreservation of human spermatozoa. III. The effect of cryoprotectants on motility. Fertil Steril 50(2), 314–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sutter P (2001). Gender reassignment and assisted reproduction. Hum. Reprod . 16(4), 612–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sutter P (2003). Donor inseminations in partners of female-to-male transsexuals: should the question be asked?. Reprod Biomed Online 6(3),382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sutter P, Kira K, Verschoor A, Hotimsky A (2002). The desire to have children and the preservation of fertility in transsexual women: A survey. Int. J. Transgenderism 6(3) [Google Scholar]

- Decuypere G, Vanhemelrijck M, Michel A, Carael B, Heylens G, Rubens R, Hoebeke P, Monstrey S (2007). Prevalence and demography of transsexualism in Belgium. Eur Psychiatry 22(3), 137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores AR, Herman JL, Gates GJ, Brown TNT (2016). How Many Adults Identify as Transgender in the United States? Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman D, Tasker F, Di Ceglie D (2002). Children and adolescents with transsexual parents referred to a specialist gender identity development service: A brief report on key developmental features. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 7(3), 423–432. [Google Scholar]

- Green R (1978). Sexual identity of thirty-seven children raised by homosexual or transsexual parents. Am J Psychiatry 135(6), 692–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green R (1998). Transsexuals’ Children. Int. J. Transgenderism 4(2). [Google Scholar]

- Hamada A, Kingsberg S, Wierckx K, Tsjoen G, Sutter PD, Knudson G, Agarwal A (2014). Semen characteristics of transwomen referred for sperm banking before sex transition: a case series. Andrologia 47(7), 832–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HW (2000). Gender reassignment and assisted reproduction : Evaluation of multiple aspects. Hum. Reprod 15(5), 987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreukels B, Haraldsen I, Cuypere GD, Richter-Appelt H, Gijs L, Cohen-Kettenis P (2012). A European network for the investigation of gender incongruence: The ENIGI initiative. Eur Psychiatry 27(6), 445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenna A, Crosby J, Huidobro C, Correa E, Duque G (2017). Semen quality before cryopreservation and after thawing in 543 patients with testicular cancer. JBRA Assisted Reproduction 21(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer W, Bockting WO, Cohen-Kettenis P, Coleman E, Diceglie D, Devor H, Gooren L, Hage JJ, Kirk S, Kuiper b., Laub D, Lawrence A, Menard Y, Patton J, Schaefer L, Webb A, Wheeler CC (2002).The Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Associations Standards of Care for Gender Identity Disorders, Sixth Version. J Psychol Human Sex 13(1), 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sapino A, Pagani A, Godano A, Bussolati G (1987). Effects of estrogens on the testis of transsexuals: A pathological and immunocytochemical study. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 411(5), 409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- T’Sjoen G, Van Caenegem E, Wierckx K (2013). Transgenderism and reproduction. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes, Diabetes and Obesity 20, 575–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walinder J (1971). Incidence and Sex Ratio of Transsexualism in Sweden. Br J Psychiatry 119(549), 195–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitze C, & Osburg S (1996). Transsexualism in Germany: Empirical data on epidemiology and application of the German Transsexuals Act during its first ten years. Arch. Sex. Behav 25(4), 409–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS (1989). Models for Longitudinal Data: A Generalized Estimating Equation Approach. Biometrics 45(1), 347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker KJ, & Lawrence AA (2009). Epidemiology of Gender Identity Disorder: Recommendations for the Standards of Care of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Int. J. Transgenderism 11(1), 8–18. [Google Scholar]