Abstract

Background: The Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system is a high-volume provider of cancer care. Women are the fastest growing patient population using VA healthcare services. Quantifying the types of cancers diagnosed among women in the VA is a critical step toward identifying needed healthcare resources for women Veterans with cancer.

Materials and Methods: We obtained data from the VA Central Cancer Registry for cancers newly diagnosed in calendar year 2010. Our analysis was limited to women diagnosed with invasive cancers (e.g., stages I-IV) between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2010, in the VA healthcare system. We evaluated frequency distributions of incident cancer diagnoses by primary anatomical site, race, and geographic region. For commonly occurring cancers, we reported distribution by stage.

Results: We identified 1,330 women diagnosed with invasive cancer in the VA healthcare system in 2010. The most commonly diagnosed cancer among women Veterans was breast (30%), followed by cancers of the respiratory (16%), gastrointestinal (12%), and gynecological systems (12%). The most commonly diagnosed cancers were similar for white and minority women, except white women were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with respiratory cancers (p < 0.01) and minority women were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with gastrointestinal cancers (p = 0.03).

Conclusions: Understanding cancer incidence among women Veterans is important for healthcare resource planning. While cancer incidence among women using the VA healthcare system is similar to U.S civilian women, the geographic dispersion and small incidence relative to male cancers raise challenges for high quality, well-coordinated cancer care within the VA.

Keywords: : women, cancer, neoplasms, Veterans, incidence

Introduction

The Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system is a high-volume provider of cancer care, caring for ∼50,000 Veterans with newly diagnosed cancers annually.1 Previous studies have demonstrated that newly diagnosed cancers seen in the VA nationally mirror those diagnosed among men in the general U.S. population.1,2 However, less is known about the cancers diagnosed among women Veterans who use the VA healthcare system for their cancer care.

Understanding cancer among women Veterans is important for several reasons. First, while the VA patient population is predominately men, women are the largest growing segment of VA healthcare system users.3 The number of women Veterans using the VA for their healthcare nearly doubled in the past decade.3 Second, women Veterans also are more likely to have a service-connected disability rating than men Veterans receiving care within the VA,3 which means that more women will be entitled to VA healthcare services for life. Moreover, the population of women Veterans within the VA is aging with the largest cohort of women between the age of 45 and 64 years3; this means that the largest group of women Veterans within the VA will be aging into the era of life when they are most likely to be diagnosed with cancer.

This creates a growing demand for women's health services within the VA, including the treatment of cancers. Particularly challenging for providing high-quality cancer care to women Veterans is the fact that, while there are significant numbers of women in the VA healthcare system nationally, the actual number treated at any one VA facility is relatively small. Volume is traditionally associated with higher quality cancer care,4,5 so the VA must overcome the challenge of a sparsely distributed population to deliver optimal cancer care to women.6

While VA provides quality cancer care, most research has been conducted with male-dominated study samples.7–11 Thus, understanding the epidemiology of women's cancer in the VA is of critical importance for understanding current health service demand and to inform future resource planning.

Materials and Methods

The analysis for this report was conducted as part of a VA data quality improvement project. In compliance with Veterans Health Administration regulations, we received documentation approving this nonresearch activity for publication.

The VA central cancer registry

The VA Central Cancer Registry (VACCR) was established in 1995 and is tasked with collecting information on all newly diagnosed cancers occurring in the national VA healthcare system. The VACCR has been previously described in detail and is reported to capture ∼90% of VA healthcare system cancers.7 In keeping with North American Association of Central Cancer Registries standards, the VACCR also collects information on cases that receive their cancer care within the VA even if they were diagnosed in the private sector.

Eligibility criteria

Our analysis was limited to women diagnosed with invasive cancers (e.g., stages I–IV) in the VA healthcare system from January 1, 2010, through December 31, 2010. There were 280 noninvasive cancers excluded from analysis. These noninvasive cancers were most commonly cervical (n = 97) or breast (n = 88). The remaining 1,330 invasive cancers were included in this analysis. Additional exclusions were made to subanalyses and are described in table footnotes. For example, 22 women with unknown race are excluded from analyses describing the racial distribution of women with cancer.

Descriptive variables

Descriptive variables included anatomic site and organ system of the cancer, stage of disease, and the patient's geographic location and race. To determine stage at diagnosis and consistent with our prior analysis, we used pathological TNM stage (primary tumor [T], regional lymph nodes [N], distant metastasis [M]) preferentially, followed by clinical TNM stage when the pathological stage was unknown or missing.1

The VA is organized into geographic regions called Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs). VISNs are not evenly divided regarding geographic land mass, general population size, or VA patient volume. Consistent with our prior analysis of cancers among all Veterans (both men and women), each woman's reporting VISN was aggregated into four larger standard geographic regions: Northeastern (VISNs 1, 2, 3, and 4), Southern (VISNs 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 16, and 17), Midwestern (VISNs 10, 11, 12, 15, and 23), and Western (VISNs 18, 19, 20, 21, and 22).1,2

We defined the primary anatomic site according to International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O-3) site and histology (i.e., type) codes from 2003.12 These codes are commonly used in pathology reports and cancer registries to capture information about the topography and morphology of neoplasms. Because of the small sample sizes in this analysis and to avoid inadvertent individual patient identification, site information is reported at the organ system level and/or at the individual site level (e.g., gynecological system and breast cancer) depending on the number of cases.

While we use the term “women,” the unit of analysis throughout this report is the specific cancer diagnosis and not unique patient. That is, a woman with multiple cancer diagnoses in 2010 would also have multiple records in the database and could potentially be included in the analysis more than once. Of note, the VACCR identifies women as those individuals whose biologic sex at birth was determined to be female. The data set used in this analysis did not contain information about gender identity.

Women Veterans by region

To descriptively assess the regional proportions of women Veterans and women Veterans diagnosed with cancer, we obtained publicly available data.13 We obtained data on the number of women Veterans in each state in 2016 and aggregated this information to align with the previously described regions (e.g., Northeastern, Southern, Midwestern, and Western).

Statistical analysis

Frequency distributions of incident cancer diagnoses were evaluated by primary anatomical site, race, and geographic region. For the most commonly occurring cancers, we also created a frequency distribution by stage at diagnosis. Tables are presented in descending order of frequency. Due to the categorical nature of these data, the characteristics of cancer cases were summarized using frequencies and proportions. These were compared by race at the organ system level using a chi-square test when a minimum of 25 cases occurred in each group. Also, regional proportions of cancer cases were compared to regional proportions of female Veteran population by chi-square. To protect Veterans' privacy, cells with fewer than 10 cases were redacted. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Most commonly diagnosed cancers

We identified 1,330 cases diagnosed with invasive cancer in the VA healthcare system in 2010. The median age at diagnosis was 57 years (59 years for white women and 54 years for minority women). For descriptive comparison, the median age at diagnosis among Veteran men during the same time period was 65 years (65 years for white men and 62 years for minority men).1

The most commonly diagnosed cancer among women Veterans was breast, accounting for 30% of all cancers (Table 1). This was followed by cancers of the respiratory (16%), gastrointestinal (12%), and gynecological systems (12%). Among respiratory cancers, lung and bronchus were the most commonly diagnosed (15%). Among gastrointestinal cancers, colon and rectum accounted for most diagnoses (7%). Among gynecological cancers, uterine cancer was the most commonly diagnosed (6%), followed by ovarian (2%), cervical (2%), and other gynecological malignancies (1%).

Table 1.

| All n (% female cancers) | White n (% white cancers) | Minority n (% minority cancers) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All sites | 1330 (100) | 982 (73.83) | 326 (24.51) |

| Breast | 402 (30.23) | 295 (30.04) | 101 (30.98) |

| Respiratory system | 207 (15.56) | 170 (17.31) | 36 (11.04) |

| Lung and bronchus | 197 (14.81) | 163 (16.60) | 33 (10.12) |

| Larynx | 10 (0.75) | — | — |

| Gastrointestinal system | 161 (12.11) | 107 (10.90) | 50 (15.34) |

| Colon | 60 (4.51) | 42 (4.28) | 18 (5.52) |

| Rectum | 28 (2.11) | — | — |

| Pancreas | 23 (1.73) | — | — |

| Liver and intrahepatic bile duct | 14 (1.05) | — | — |

| Other digestive | 36 (2.71) | 24 (2.44) | 11 (3.37) |

| Gynecological system | 154 (11.58) | 110 (11.20) | 39 (11.96) |

| Uterine corpus | 75 (5.64) | 54 (5.50) | 19 (5.83) |

| Ovary | 32 (2.41) | — | — |

| Uterine cervix | 29 (2.18) | 18 (1.83) | 10 (3.07) |

| Other gynecological | 18 (1.35) | — | — |

| Hematologic system | 112 (8.42) | 87 (8.86) | 23 (7.06) |

| Lymphoma | 53 (3.98) | 39 (3.97) | 13 (3.99) |

| Leukemia | 28 (2.11) | — | — |

| Bone marrow | 19 (1.43) | 19 (1.93) | 0 |

| Myeloma | 12 (0.90) | — | — |

| Endocrine system | 65 (4.89) | 42 (4.28) | 21 (6.44) |

| Thyroid | 53 (3.98) | 35 (3.56) | 16 (4.91) |

| Other endocrine | 12 (0.90) | — | — |

| Melanoma | 59 (4.44) | 59 (6.01) | 0 |

| Central nervous system | 53 (3.98) | 38 (3.87) | 15 (4.60) |

| Brain | 17 (1.28) | — | — |

| Other central nervous system | 36 (2.71) | 22 (2.24) | 14 (4.29) |

| Urinary system | 48 (3.61) | 25 (2.55) | 22 (6.75) |

| Kidney and renal pelvis | 37 (2.78) | 18 (1.83) | 18 (5.52) |

| Other urinary | 11 (0.83) | — | — |

| Head and neck | 27 (2.03) | — | — |

| Other and unspecified primary sitesc | 42 (3.16) | 30 (3.05) | 12 (3.68) |

Excluded cases with in situ cancer (n = 280) for each column, and cancer cases with unknown race (n = 22) for White and Minority columns.

To protect Veterans' privacy, cells with fewer than 10 cases were redacted and are noted with a dash.

Other includes soft tissue (including heart), bones and joints, eye and orbit, mesothelioma, non-melanoma skin, and miscellaneous and invalid codes.

Newly diagnosed cancers by race

We also evaluated the racial composition of women with newly diagnosed cancers (Tables 1 and 2). In VA, most patients are non-Hispanic white (66%), followed by African Americans (19%),and Hispanics (9%).14 Note that ethnicity (i.e., Hispanic status) is not captured in the cancer registry dataset used for this study.

Table 2.

Incident Cancers by Race in Top Five Systems for Female Veteran Affairs Patients, 2010a

| White n (% white cancers) | Minority n (% minority cancers) | pb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All cancers n (% all) | 982 (73.83) | 326 (24.51) | |

| Breast | 295 (30.04) | 101 (30.98) | 0.75 |

| Respiratory | 170 (17.31) | 36 (11.04) | <0.01 |

| Gynecological | 110 (11.20) | 39 (11.96) | 0.71 |

| Gastrointestinal | 107 (10.90) | 50 (15.34) | 0.03 |

| Hematologic | 87 (8.86) | 23 (7.06) | — |

Excluded cases with unknown race (n = 22).

Chi-square p-values are shown for white-minority comparison within organ systems with a minimum of 25 cases in each category.

We assessed the most commonly diagnosed cancers and those sex-specific cancers affecting women (e.g., gynecological cancers). The most commonly diagnosed cancer for both white and minority women was breast cancer (30% white and 31% minority). Following breast cancer, the rank order of the most commonly diagnosed cancers varied by race (Table 2). Respiratory cancers (17%), gynecological cancers (11%), and gastroenterological cancers (11%) were most common among white women. Gastroenterological (15%), gynecological (12%), and respiratory (11%) cancers were most common among minority women. There was no significant difference in breast cancer or gynecological diagnoses by race. However, there were statistically significant differences between racial groups for respiratory (p < 0.01) and gastrointestinal (p = 0.03) cancers.

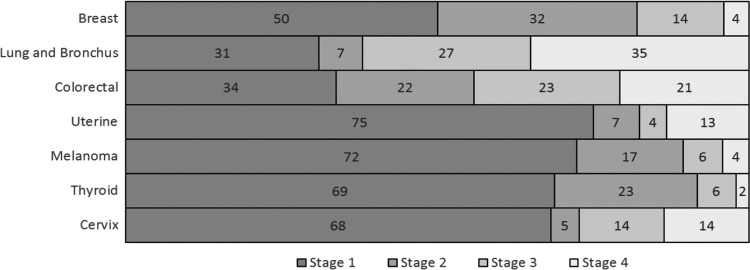

Newly diagnosed cancers by stage

Figure 1 presents cancer diagnoses by stage at diagnosis for seven prevalent sites. Cases that were not staged were excluded from the calculation for the figure. Most women with breast cancer were diagnosed with early stage disease (stage I = 50%, stage II = 32%). For cancers of the lung and bronchus, for which the VA has screening programs, ∼38% were diagnosed with stage 1 (31%) or stage II (7%) disease. For cancers that are more commonly detected through screening, such as colorectal cancer (34%) and cervical (68%) cancers, there was a higher proportion of cancers diagnosed at stage I than other stages.

FIG. 1.

Stage distribution of prevalent and female-related incident cancers as percentage of number staged.a,b. aThe listed cancers are the top five non-gynecologic cancers plus two gynecologic cancers of interest. Cancers are shown in order of prevalence from top to bottom. bThe listed cancers had TNM pathology or TMN clinical stage information for 76%–97% of total diagnoses. TNM clinical was used when TNM pathology was UMI (unavailable, missing, or invalid).

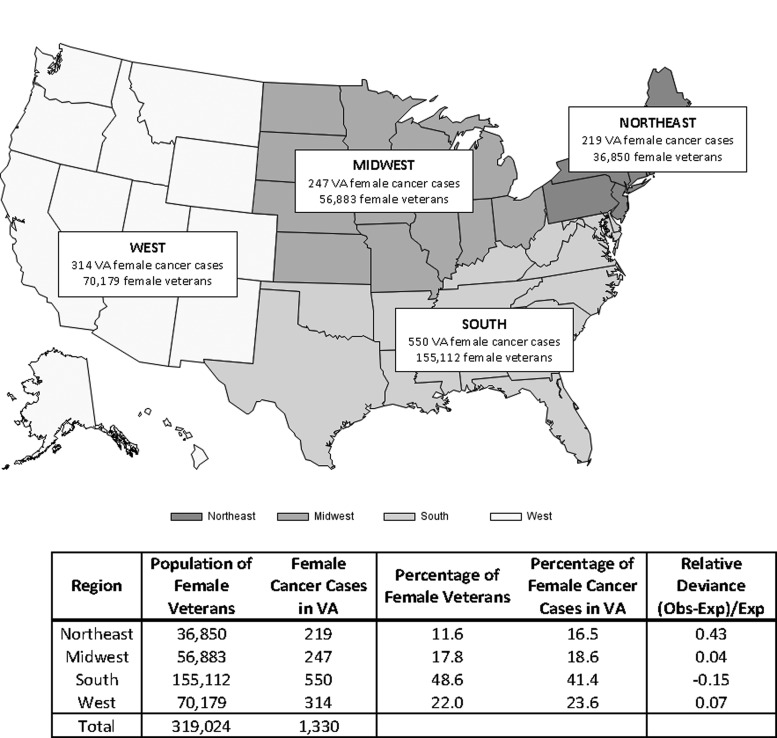

Newly diagnosed cancers by geographic region

Cancers were most commonly diagnosed among women living in the southern region (41%), followed by the western region (24%), midwestern region (19%), and northeastern region (17%). Because matched age-specific information was not available, Figure 2 is not adjusted for the proportion of women living in these regions; instead, we present a descriptive assessment comparing the overall proportion of women Veterans in each region with the proportion of women Veterans in each region who were diagnosed with cancer. The population of women Veterans living in each state varies considerably.13 The proportion of cancer cases in each region compared to the underlying regional women Veterans population was significantly different overall (p < 0.0001); however, the relative deviance of the midwest and west proportions was each 0.04 and 0.07, respectively (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Distribution of Incident Cancers among Female Veterans in 2010 by VA Regiona. aRegions were created based on VISNS: Northeastern (VISNs 1, 2, 3, and 4), Southern (VISNs 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 16, and 17), Midwestern (VISNs 10, 11, 12, 15, and 23), and Western (VISNs 18, 19, 20, 21, and 22). VA, Veterans Affairs; VISN, Veterans integrated service network.

Discussion

Women Veterans and VA cancer care

While the VA treats relatively few women newly diagnosed with cancer each year (n ∼ 1,330) compared with the number of women treated in the United States overall (n ∼ 852,630),15 this is an important population to consider for several reasons. First, women comprise a growing proportion of the U.S. military service members and, subsequently, are the fastest growing segment of the VA patient population.3 Understanding the VA cancer burden for women is critically important to plan for future needs.

Second, through national healthcare policy changes, for example the Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act of 2014 or “Choice Act,” the VA is undergoing broad structural changes that may impact the delivery of cancer care.16 The Choice Act was introduced to improve timely access to healthcare at non-VA medical centers and to increase staffing and resource availability at VA medical centers.17 Most individual VA facilities treat a small number of women with gender-specific cancers annually, thus many of these women will be sent outside the VA healthcare system to receive all or a portion of their cancer care.

The proportion of women who receive their cancer care exclusively in the VA healthcare system versus dually through VA and non-VA providers has not been well described. The limited evidence that exists suggests that care coordination may be particularly problematic since women with gynecological cancers may concurrently use multiple healthcare systems, in other words both VA and community-based care.18 It seems reasonable that these findings in the context of gynecological cancers will be applicable to other types of cancers that predominately impact women (e.g., breast cancer).

Third, because many cancers that predominately affect women (e.g., breast and gynecological cancers) are relatively infrequently diagnosed and treated in the VA healthcare system relative to other cancer types, the quality of care delivery for these patients has not been well studied. While the quality of VA cancer care more broadly has been evaluated and found to be high quality and equal to or better than other healthcare systems,7–10 whether this translates into quality cancer care for women is not well understood.

As a healthcare system, the VA is moving toward the provision of specialty care services through outside, community-based providers. Because the number of women Veterans treated with cancer in the VA is relatively small, the healthcare system may face important care delivery questions. Many larger VA facilities have formal affiliations with National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers. For these centers, there may be opportunities to forge connections based on patient volume and ensure that women Veterans receive optimal care for gender-specific malignancies. For smaller VA facilities with even fewer numbers of gender-specific malignancies, there may be a need to identify local high-volume community partners to assist in delivering high-quality care.

A qualitative study conducted to describe issues for women Veterans seeking care for gynecologic malignancies reported that care was provided through a variety of VA and community-based sources.18 The key stakeholders interviewed in the study reported that this resulted in potential problems with care fragmentation, lack of role clarity and care tracking, difficulties associated with VA and community provider communication, patient communication, and patient records exchange, among others.18 Overall (i.e., beyond cancer care), women are more likely than men to use non-VA care and many women Veterans receive some portion of their cancer screening—specifically mammograms outside the VA.3 To our knowledge, studies assessing care coordination and quality among a broad population of women Veterans have not been conducted.

Age among women Veterans diagnosed with cancer

Age is a key risk factor for cancer diagnosis. Women Veterans are an average of 15 years younger than their male counterparts (48 years vs. 63 years old).19 The average age of cancer diagnosis varies by disease. For example, the median age of women diagnosed with breast cancer in the United States is 62 years.20 Fewer than 5% of breast cancers are diagnosed in women younger than 40 years.21 Breast cancer rates increase after age 40 and are highest for older women (aged 70 years and older).20 Because the majority of women Veterans are younger (48 years on average), cancer incidence among this population is expected to increase as the VA healthcare system cares for a growing number of women who are aging.

Race among women Veterans diagnosed with cancer

Among women Veterans with cancer, 25% were racial minorities. This is slightly lower than among the general population of women Veterans, which reports an estimated 39% minority population.3 However, diversity is growing among Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom (OIF/OEF) and other incoming military Veteran cohorts.

The relationship between cancer diagnosis, cancer-related mortality, and race is complex. For example, black women in the United States tend to be diagnosed with breast cancer at an earlier age than white women (59 years vs. 63 years).20 Among women receiving care in the VA, black race is associated with higher rates of receipt of colorectal cancer screening.22 In addition, cancer incidence is often lower for minorities, but mortality is higher. For example, in the general U.S. population, African American women have lower breast cancer incidence and higher breast cancer-related mortality compared to white women.21

While our analysis did not evaluate all cause or cancer-specific mortality, the lower incidence among racial minorities is not without precedence. Our analysis also identified that many women Veterans with cancer live in the southern region of the United States. Small sample sizes prevented us from investigating the distribution of women's cancers by race within each geographic area; however, anecdotally we suspect that there is greater racial diversity in the south.

The VA healthcare system is often considered an equal access system. As such, racial disparities in cancer care may be attenuated in the VA.10,11,23,24 However, relatively few women Veterans have been included in previous racial disparity studies in the VA and this may be an area of future research. It is worth noting that minority women who strongly identify with their Veteran status may prefer to receive their healthcare in the VA as opposed to other healthcare facilities.25 As such, when cancer care for women Veterans is delivered outside of the VA (e.g., because of the Choice Act or through an academically affiliated institution), this may be disproportionally perceived as suboptimal by minority women.

Related VA initiatives

We highlight three relevant initiatives within the VA healthcare system that support high-quality and well-coordinated cancer care delivery for women Veterans. First, the Breast Care Registry was initiated in 2014 to establish a central repository for information about the full spectrum of breast healthcare ranging from breast cancer screening and test results, to treatment and follow-up for the national population of women Veterans engaged in VA healthcare.26

Second, the Precision Oncology Program began in 2015 and, a year later, was expanded throughout the VA system. This program, which is available for both men and women Veterans, provides targeted genomic sequencing of an individual patient's tumor. Cancer providers receive this patient-level diagnostic information along with information about FDA-approved targeted agents specific for that patient's specific tumor mutation. Third, the VA has developed a Telegenomics Program currently available regionally.27 This program provides telegenomics counseling remotely for patients with cancer or who are at increased risk for hereditary malignancies, including BRCA mutations.

Limitations

Our analysis had several limitations. It is cross-sectional in nature and thus cannot give a perspective on longitudinal changes in cancer among Veteran women. A recent study by Colonna et al evaluated trends in VA breast cancer and demonstrated that breast cancer incidence in the VA increased over time and the age of women diagnosed with breast cancer decreased.6 While the incident numbers were similar in the Colonna study and our analysis, we were unable to report information about longitudinal changes in incidence. We were also unable to obtain information about mortality for this analysis and are therefore unable to comment on patients' survival.

Our analysis is limited to women with invasive (stages I–IV) cancers. Many cancers affecting women, particularly breast cancer, may be detected during screening and diagnosed before they reach stage I disease. These noninvasive cancers are not included in the analysis presented in this report, but are described in Table 3. Regional data on the underlying population of women Veterans were not available for a comparable time period, thus our descriptive analysis comparing the proportion of women Veterans living in each region with the proportion of women diagnosed with cancer in each region may underestimate the cancer population (cancer data from 2010, women Veterans population data from 2016).

Table 3.

In Situ Cancers by Site in Female Veteran Affairs Patients, 2010

| Cancer site | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gynecological system | 124 | 44.29 |

| Cervix uteri | 97 | 34.64 |

| Other | 27 | 9.64 |

| Breast | 88 | 31.43 |

| Other | 68 | 24.29 |

| Total | 280 |

This analysis builds upon an earlier report describing cancer among users of the VA healthcare system, including both men and women.1 At the time of that report, 2010 was the most currently internally validated VACCR data. For consistency with that work, we also use 2010 data in this article. While newer data are available, there is still a sizeable time lag in data availability. While more women are seeking VA healthcare, these women tend to be younger than when typically diagnosed with cancer. Thus, while over time we expect an increase in the number of women treated in the VA for cancer, the increase in cancers may be proportionally slower than the increase in women using services overall. Despite these limitations, our analysis has important implications for policy and practice.

Implications for policy and practice

The increasing number of women receiving healthcare in the VA will likely translate to more women in the VA being diagnosed with cancer and needing treatment. We identified a small, yet clinically significant number of women seeking VA cancer care annually (i.e., ∼1,330 women in the year 2010). The small number of women diagnosed with cancer at any given VA facility, coupled with changes in national VA healthcare policy, results in the potential for women Veterans with cancer to receive fragmented care.

As the population of women receiving VA healthcare grows, there are potential healthcare policy implications. Women with cancer may benefit from cancer care coordinators that span both VA and non-VA services. There may be an increased need to engage not only primary care but also women's health services with the VA oncology community. This is important for cancer prevention and screening, as well as optimal survivorship care. As primary care has developed specialized clinical care models and designated providers dedicated to treating women, there may be a need to develop national or regional gender-specific cancer support programs to assist women Veterans throughout their cancer care journey. Understanding the number and types of cancers diagnosed among women Veterans is an important foundation to quantifying the problem and planning future cancer care delivery.

Conclusions

Understanding cancer incidence among women Veterans is important for healthcare resource planning. While cancer incidence among women using the VA healthcare system is similar to U.S. civilian women, the geographic dispersion and small incidence relative to male cancers raise challenges for high quality, well-coordinated cancer care within the VA.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Zullig and Goldstein are supported by VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Career Development Awards (CDA) CDA 13–025 and CDA 13–263, respectively. This work was supported by the Center of Innovation for Health Services Research in Primary Care (CIN 13–410) at the Durham VA Medical Center and the VA Cooperative Studies Epidemiology Center (CSP 602). We thank the VA cancer registrars and VACCR staff for their data collection and related efforts. We also thank Dr. Susan Frayne, Fay Saechao, and the Women's Health Evaluation Initiative (WHEI) for their support and provision of data.

Author Disclosure Statement

The views in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or of Duke University. The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this work to disclose.

References

- 1. Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Sims KJ, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the US Veterans Affairs Health Care System: 2010 update. Mil Med 2017;182:e1883–e1891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Dorn RA, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Mil Med 2012;177:693–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frayne SM, Phibbs CS, Saechao F, et al. Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 3 Sociodemographics, Utilization, Costs of Care, and Health Profile. Women's Health Evaluation Initiative, 2014. Available at: https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/womenshealth/docs/sourcebook_vol_3_final.pdf Accessed August15, 2017

- 4. Pozzar RA, Berry DL. Patient-centered research priorities in ovarian cancer: A systematic review of potential determinants of guideline care. Gynecol Oncol 2017;147:714–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roohan PJ, Bickell NA, Baptiste MS, Therriault GD, Ferrara EP, Siu AL. Hospital volume differences and five-year survival from breast cancer. Am J Public Health 1998;88:454–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Colonna S, Halwani A, Ying J, Buys S, Sweeney C. Women with breast cancer in the Veterans Health Administration: Demographics, breast cancer characteristics, and trends. Med Care 2015;53:S149–S155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jackson GL, Melton LD, Abbott DH, et al. Quality of nonmetastatic colorectal cancer care in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3176–3181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Keating NL, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, et al. Quality of care for older patients with cancer in the Veterans Health Administration versus the private sector: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:727–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Landrum MB, Keating NL, Lamont EB, et al. Survival of older patients with cancer in the Veterans Health Administration Versus fee-for-service medicare. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1072–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zullig LL, Carpenter WR, Provenzale D, Weinberger M, Reeve BB, Jackson GL. Examining potential colorectal cancer care disparities in the Veterans Affairs health care system. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3579–3584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Weinberger M, Provenzale D, Reeve BB, Carpenter WR. An examination of racial differences in process and outcome of colorectal cancer care quality among users of the Veterans affairs health care system. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2013;12:255–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Percy C, Fritz A, Jack A, Shanmuganatahn S, Sobin L, Parkin D. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 13. US. Department of Veteran Affairs. Women Veterans Population Fact Sheet, 2016. Available at: https://www.va.gov/womenvet/docs/womenveteranspopulationfactsheet.pdf Accessed June12, 2018

- 14. US. Department of Veterans Affairs. Profile of Women Veterans, 2015. Available at: https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/specialreports/women_veterans_profile_12_22_2016.pdf Accessed June12, 2018

- 15. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:7–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zullig LL, Goldstein KM, Bosworth HB. Changes in the delivery of Veterans Affairs Cancer Care: Ensuring delivery of coordinated, quality cancer care in a time of uncertainty. J Oncol Pract 2017;13:709–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. US Department of Veteran Affairs. Fact Sheet: Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act of 2014 (“Choice Act”), 2014. Available at: https://www.va.gov/opa/choiceact/documents/choice-act-summary.pdf Accessed June12, 2018

- 18. Zuchowski JL, Chrystal JG, Hamilton AB, et al. Coordinating care across health care systems for Veterans with gynecologic malignancies: A qualitative analysis. Med Care 2017;55 Suppl 7 Suppl 1:S53–S60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. US Department of Veteran Affairs. Facts and Statistics about Women Veterans. Available at: https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/WOMENSHEALTH/latestinformation/facts.asp Accessed June12, 2018

- 20. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2014, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/, based on November 2016. SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2017. Accessed June12, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 21. American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts and Figures 2017-2018, 2017. Available at: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2017-2018.pdf Accessed June12, 2018

- 22. May FP, Yano EM, Provenzale D, Neil Steers W, Washington DL. The association between primary source of healthcare coverage and colorectal cancer screening among US Veterans. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:1923–1932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Williams CD, Salama JK, Moghanaki D, Karas TZ, Kelley MJ. Impact of race on treatment and survival among U.S. Veterans with early-stage lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:1672–1681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zullig LL, Carpenter WR, Provenzale DT, et al. The association of race with timeliness of care and survival among Veterans Affairs health care system patients with late-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Manag Res 2013;5:157–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harada ND, Damron-Rodriguez J, Villa VM, et al. Veteran identity and race/ethnicity: Influences on VA outpatient care utilization. Med Care 2002;40:I117–I128 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. US Department of Veteran Affairs. Breast Care Registry (BCR) User Guide. Available at: https://www.va.gov/vdl/documents/Clinical/Breast_Care_Registry/hreg_bcrv2_userguide_20150609.pdf Accessed June12, 2018

- 27. Venne V, Meyer LJ. Genetics and the Veterans Health Administration. Genet Med 2014;16:573–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]