Abstract

Objective

In large-vessel occlusion, endovascular therapy is superior to medical management alone in achieving recanalisation. Reducing time delays to revascularisation in patients with large-vessel occlusion is important to improving outcome.

Patients and methods

A campaign was implemented in the Central Denmark Region targeting the identification of patients with large-vessel occlusion for direct transport to a comprehensive stroke centre. Time delays and outcomes before and after the intervention were assessed.

Results

A total of 476 patients (153 pre-intervention and 323 post-intervention) were included. They were treated with either intravenous tissue plasminogen activator or endovascular treatment (alone or in combination with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator). Endovascular therapy patients’ median system delay was reduced from 234 to 185 min (adjusted relative risk delay 0.79 (95% confidence interval: 0.67–0.93)). The in-hospital delay was the main driver with an adjusted relative risk delay of 0.76 (confidence interval: 0.62–0.94), while pre-hospital delay was almost significantly reduced with an adjusted relative delay of 0.86 (confidence interval: 0.71–1.04). This was achieved without increasing the intravenous tissue plasminogen activator-treated patients’ delay. Significantly more patients treated with endovascular therapy in the post-interventional period achieved functional independence (62% versus 43%), corresponding to an adjusted odds ratio of 3.08 (95% confidence interval: 1.08–8.78).

Conclusion

Direct transfer of patients with suspected large-vessel occlusion to a comprehensive stroke centre leads to shorter treatment times for endovascular therapy patients and is, in turn, associated with an increase in functional independence. We recorded no adverse effects on intravenous tissue plasminogen activator treatment times or outcome.

Keywords: Acute stroke, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator, endovascular treatment, system delay, modified Rankin Scale

Introduction

In acute ischaemic stroke (AIS), reperfusion can be achieved with intravenous (IV) tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)1 or endovascular therapy (EVT).2 Both treatments are critically time dependent.3,4 In patients with a large-vessel occlusion (LVO) and severe neurological deficit, EVT is superior to IV tPA as successful recanalisation is achieved in 70–80% of EVT cases,5 but only in 30% of IV tPA cases.6 Delivery of EVT is challenged by transport of the patient to a capable facility, and clear pre-hospital and inter-hospital transport guidelines are essential to minimising time delays. With better logistics, treatment can be offered more rapidly and to more patients.7–9

The aim of the present study was to reduce system delay by educating and training medical dispatch staff and paramedics (emergency medical service, EMS) in recognising suspected LVO and by introducing subsequent direct transport to a comprehensive stroke centre (CSC). We wanted to shorten time to EVT (‘groin puncture’) accepting the risk of extending time delay to IV tPA treatment, since these patients could bypass a closer primary stroke centre (PSC). The effect of this intervention on time delays was followed for 18 months and compared with the 10 months leading up to the intervention.

Methods

Setting and design

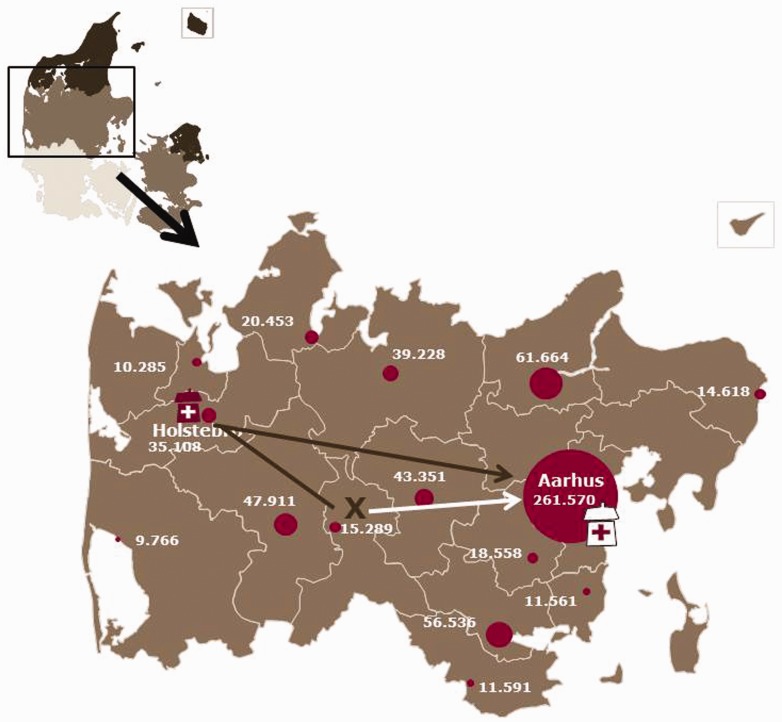

The study was a population-based before-and-after study conducted in the Central Denmark Region among patients with AIS who were admitted for reperfusion therapy with IV tPA and/or EVT. The Central Denmark Region covers an area of approximately 13,000 km2 (5000 square mile) and has a catchment population of 1.3 million. In the Western part of the region, AIS is treated at a PSC with IV tPA capabilities. In the Eastern part of the region, a CSC has both IV tPA and EVT capabilities. The two centres are 120 km (75 mile) apart (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of Denmark in left upper corner focusing on Central Denmark Region with the largest towns and the number of inhabitants. The total number of inhabitants is 1.3 million. The comprehensive stroke centre is marked by the white hospital in Aarhus in the Eastern part of the region. The primary stroke centre (PSC) is marked by the red hospital in the Western part, in the city of Holstebro. The distance between the two hospitals is 120 km (75 mile). If a patient living at the ‘X’ on the map suffers a stroke and is admitted to the PSC, he is subjected to a long transportation and in-hospital delay if endovascular therapy (EVT) is needed (black line). Bypassing (white arrow) would result in shorter delay to endovascular treatment (EVT).

The study period was divided into a pre- (1 June 2011–31 March 2012) and a post-interventional period (1 April 2012–30 September 2013) reflecting the timing of the education, training and triage campaign.

The study was based on data obtained from the Danish Stroke Registry and the EMS. The Danish Stroke Registry is a clinical registry which holds data on patient characteristics and care, including IV tPA and EVT, for all acute stroke patients in Denmark.10 The EMS holds pre-hospital data from all operating agencies. Unambiguous individual-level linkage between the databases used in the present study was possible using the civil registration number, a unique 10-digit personal identification number assigned to every Danish citizen. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (record no. 1-16-02-440-13).

The intervention consisted of a simple pre-hospital stroke triage questionnaire developed by stroke physicians in collaboration with the EMS to ensure ease of use and minimal time consumption. EMS dispatch personnel and ambulance paramedics were taught how to use the questionnaire. It consisted of four questions (see Table 1): (1) Is there eye deviation? (2) Is the patient awake? (3) Is an arm or leg paretic and not anti-gravity? (4) Are there any language problems? The combination of ‘yes’ to questions 1 + 2 or 2 + 3 + 4 meant that there was clinical suspicion of LVO. The dispatchers were then instructed to prioritise transportation to the CSC for evaluation, thus prioritising EVT even if it meant bypassing a nearer PSC where IV tPA could have been administered at an earlier time point. The hospitals were pre-notified routinely in both time periods.

Table 1.

The screening tool that dispatchers and ambulance personnel used to screen for LVO (‘big stroke’). If questions 1 + 2 were answered positively or if questions 2 + 3 + 4 were answered positively, the patient was transported directly to the comprehensive stroke centre under suspicion of ‘big stroke’.

| Questions: | Yes | Yes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Is there eye deviation? | X | |

| 2. Is the patient awake? | X | X |

| 3. Is arm or leg paretic and not anti-gravity? | X | |

| 4. Are there any language problems? | X |

Study population

Excluded were self-presenters, patients without EMS data, patients referred from outside the region, patients without time data and AIS patients not treated with acute revascularisation therapy. A flow chart of the study population is presented in Figure 2. We identified a total of 476 eligible patients who received revascularisation therapy; 153 patients in the pre-interventional period and 323 in the post-interventional period.

Figure 2.

Flow chart presenting study patient inclusion. DSR: Danish Stroke Registry.

Patients were considered potentially eligible for IV tPA if treatment could be performed within a maximum of 4.5 h after symptom onset, blood pressure ≤ 185/110 mmHg, international normalised ratio ≤ 1.7 and after imaging had excluded intracranial bleeding or a very large infarct (more than a third of the middle cerebral artery territory). EVT was recommended in conjunction with IV tPA treatment if a proximal artery occlusion was seen (internal carotid artery, basilar artery, the main stem or second division of the middle cerebral artery), presenting National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) was at least 10, groin puncture could be made less than 6 h after symptom onset and the patient was living independently. The local guidelines for IV tPA and EVT treatment did not change during the study periods.

Outcomes

Patient delay is defined as the time period from symptom onset to the first contact to the EMS. Pre-hospital delay is the time period from the first EMS contact to arrival at the first hospital. In-hospital delay is the time period from arrival at the first hospital to initiation of IV tPA infusion (for IV tPA patients) or groin puncture for EVT patients, whether this was preceded by IV tPA or not. Note that for a LVO patient, in-hospital delay includes transfer from PSC to CSC. Pre-hospital and in-hospital delays are collectively referred to as system delay, while the whole period from symptom onset to treatment initiation is coined treatment delay.

For EVT patients admitted to the PSC, IV tPA was initiated before inter-hospital transportation (‘drip-and-ship’). This has been the standard procedure since 2010. The calculation of various delays was based on pre-hospital data registered by the EMS providers (Falck A/S and Response A/S, Aarhus, Denmark) and data registered in the Danish Stroke Registry.

The modified Rankin Scale (mRS) was assessed in the outpatient clinic at 90-day follow-up in both the pre-interventional and post-interventional group.

Statistical analysis

Dichotomous data are presented as percentages. Continuous variables are presented as medians with corresponding interquartile ranges (IQR). Patients were stratified according to type of reperfusion method (IV tPA and EVT alone or in combination with IV tPA, respectively). Time delays were compared using multivariable linear regression. A log transformation of the time delays was made in order to obtain normal distribution.

Logistic regression was used to calculate crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) for a 90-day mRS score 0–2 comparing the post-interventional group with the pre-interventional group. In addition, a multivariate ordinal logistic regression was used to estimate the crude and adjusted OR of any improvement in mRS in the post-interventional group compared with the pre-interventional group. Adjustments were made for sex, age, baseline characteristics, admission NIHSS, distance from pickup address to the nearest revascularisation centre, type of revascularisation therapy, quarter (season) of year and hours stratified into four groups: 1: 24.00–05.59, 2: 06.00–11.59, 3: 12.00–17.59 and 4: 18.00–23.59. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

In the pre-interventional period, 187 of 1212 (15.4%) patients received revascularisation therapy. This number included 140 (11.6%) who received only IV tPA, 10 (0.8%) who received only EVT and 37 (3.1%) who received both. This number should be compared with a total of 400 of 3025 (13.2%) patients in the post-interventional period (p = 0.11) of whom 304 (10.0%) received only IV tPA, 20 (0.7%) who received only EVT and 76 (2.5%) who received both. (An administrative change initiated 1 April 2012 meant that more patients with suspected stroke were admitted directly to Neurology.) The number of patients who remained after the described exclusions comprised a total of 153 patients who had been treated in the pre-intervention period (118 treated with IV tPA and 35 with EVT) and 323 patients who had been treated in the post-intervention period (258 treated with IV tPA and 65 with EVT). Table 2 presents the demographic data of the patients in the pre- and post-interventional periods.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients before and after the intervention.

| Pre- interventional N = 153 | Post- interventional N = 323 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 68 (59–77) | 71 (62–78) |

| Women (%) | 37.9 | 38.7 |

| Admission NIHSS (IQR) | 7 (3–13) | 6 (3–12) |

| Co-morbid conditions (%) | ||

| Hypertension | 59.5 | 61.1 |

| Diabetes | 14.5 | 13.6 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 23.5 | 24.2 |

| Previous stroke | 12.4 | 17.3 |

| Delays, median (IQR), min | ||

| Patient delay | 36 (14–101) | 48 (15–107) |

| Pre-hospital delay | 55 (39–70) | 56 (43–69) |

| In-hospital | 66 (52–111) | 57 (44–94) |

| System delay | 127 (101–175) | 119 (98–156) |

| Treatment delay | 202 (145–262) | 192 (144–251) |

| Distance transported, median (IQR), km | 36 (13–50) | 39 (18–48) |

| Clinical characteristics (IQR) | ||

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | 26 (24–29) | 26 (23–29) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 152 (140–170) | 155 (136–170) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 84 (78–92) | 80 (74–90) |

| Life style factors | ||

| Active or previous smokers (%) | 60.8 | 62.5 |

| Alcohol > 14 units/ week (%) | 86.3 | 82.0 |

IQR: interquartile range; NIHSS: National Institute of Health Stroke Scale.

Patient delay is the time from onset to first contact to an emergency dispatcher. Pre-hospital delay is time from contact to arrival at the first hospital. In-hospital delay is time from arrival at first hospital to initiation of treatment. System delay is pre- and in-hospital delay. Treatment delay is the period from symptom onset to start of treatment. Distance transported is distance from pickup to arrival at the first hospital.

The main goal of the study was to reduce system delay for EVT patients. This was achieved as demonstrated in Table 3. The median system delay for EVT patients fell from 234 min (IQR 184–282) to 185 min (IQR 141–226), corresponding to an adjusted relative delay of 0.79 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.67–0.93). The reduction in delay occurred both in the pre-hospital phase (adjusted relative delay 0.86, 95% CI: 0.71–1.04) and the in-hospital phase (adjusted relative delay 0.76, 95% CI: 0.62–0.94) even if it did not reach statistical significance in the pre-hospital phase.

Table 3.

Time delays before and after the intervention for patients treated with endovascular therapy (EVT) alone or with intravenous (IV) tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and IV tPA only.

| Time delays | EVT Pre-interventiona (n = 35) | EVT Post-interventiona (n = 65) | Adjusted relative delayb | IV tPA pre-interventiona (n = 118) | IV tPA post-interventiona (n = 258) | Adjusted relative delayb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System delay | 234 (184–282) | 185 (141–226) | 0.79 (0.67–0.93) | 119 (96–143) | 112 (92–140) | 0.99 (0.92–1.07) |

| Pre-hospital | 64 (45–76) | 58 (43–74) | 0.86 (0.71–1.04) | 53 (38–68) | 56 (43–69) | 1.00 (0.92–1.08) |

| In-hospital delay | 173 (119–227) | 115 (90–156) | 0.76 (0.62–0.94) | 59 (50–73) | 51 (42–71) | 0.97 (0.87–1.08) |

Adjusted relative delays are shown with 95% confidence intervals in brackets.

Median (interquartile range).

Adjusted for distance from pickup address to the nearest revascularisation centre, type of revascularisation therapy, quarter (season) of year, hours stratified into four groups, sex, age at admission, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale score before revascularisation therapy.

Reducing EVT patients’ delay could potentially increase delay in patients eligible for IV tPA through bypass of the PSC if LVO was suspected. However, the present study found no increase in either the pre-hospital or in-hospital delay for the IV tPA patients (adjusted relative delay 1.00 (95% CI: 0.92–1.08) and 0.97 (95% CI: 0.87–1.08), respectively). The rate of good outcome (mRS 0–2) among the patients who bypassed the PSC and were treated with EVT was not significantly different from the outcome of patients admitted from the catchment area of the CSC (p = 0.42.)

We found a significantly higher chance of functional independence (mRS 0–2) after 90 days among EVT patients treated in the post-interventional period than among the pre-interventional patients with a total of 62% (40/65) versus a total of 43% (15/35) achieving functional independence. This corresponded to an adjusted OR of 3.08 (95% CI: 1.08–8.78). For the IV tPA patients, the adjusted OR for mRS 0–2 did not change, OR being 1.11 (95% CI: 0.58–2.14), see Table 4.

Table 4.

Percentage of intravenous (IV) tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and endovascular therapy (EVT) treated patients achieving a modified Rankin Score (mRS) of 0–2 at 90 days after the stroke in the pre- and post-interventional period, respectively.

| mRS 0–2 pre- intervention | mRS 0–2 post- intervention | Crude OR | Adjusted ORa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV tPA | 75% (88/118) | 75% (194/258) | 1.01 (0.62–1.63) | 1.11 (0.58–2.14) |

| EVT | 43% (15/35) | 62% (40/65) | 2.13 (0.93–4.92) | 3.08 (1.08–8.78) |

Crude and adjusted odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals for 90-day mRS 0–2 when comparing the post-interventional group with the pre-interventional group according to type of revascularisation treatment.

Adjusted for distance from pickup address to the nearest revascularisation centre, type of revascularisation therapy, quarter (season) of year, hours stratified into four groups, gender, age at admission, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale score before revascularisation therapy.

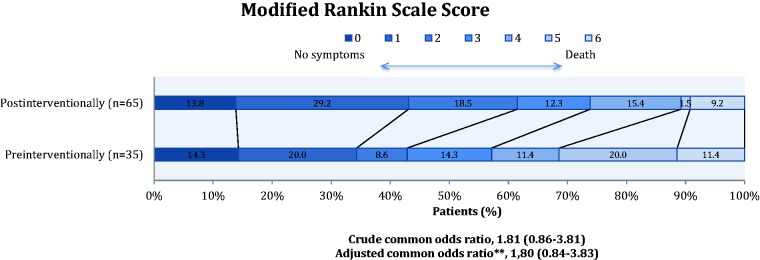

For patients treated with EVT, shift analysis using multivariate ordinal logistic regression showed a non-significant difference between the post-interventional and the pre-interventional group in terms of overall distribution of mRS scores; adjusted common OR 1.88 (0.88–4.02).

Figure 3 shows the pre- and post-interventional outcome.

Figure 3.

Modified Rankin Scale at 90 days comparing the pre- and post-intervention group for patients treated with endovascular therapy alone or with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator. **Adjusted for distance from pickup address to the nearest revascularisation centre, type of revascularisation therapy, quarter (season) of year, hours stratified into four groups, sex, age at admission, total National Institute of Health Stroke Scale score before revascularisation therapy.

Discussion

Introduction of a simple pre-hospital stroke triage and education and training of EMS personnel allowing them to recognise LVO was associated with a significant reduction in system delay. This reduction was driven largely by a reduction in in-hospital delay. Pre-hospital delay did not change significantly. Since in-hospital delay is time from arrival at the first hospital to groin puncture for EVT patients, direct transfer to CSC would result in reduction in in-hospital delay. The reduction in delay for EVT patients was achieved without significantly prolonging the delay for IV tPA patients who bypassed the PSC due to suspicion of LVO. The reduction in delay for EVT patients was associated with a significant increase in the proportion of patients reaching functional independence after the stroke without changing functional independence in patients eligible of IV tPA only.

The saying ‘Time is brain’ is true for all strokes,11 but especially so for LVO, the most severe form of stroke.12,13 The chance of a good outcome is strongly associated with time delay before treatment.4 Furthermore, EVT recanalises a LVO more successfully than IV tPA alone, and therefore early triage to a CSC is critical.

Patient delay is a significant source of lost time for AIS patients. Half of the pre-hospital delay is related to hesitation in seeking medical assistance after symptom onset.14 Moreover, activation of services other than EMS further delays care. A study from the United Kingdom showed a median 123 min delay from symptom onset to arrival at the hospital for those calling the EMS, which should be compared with a median 432 min delay for patients who first consulted their primary care physician.15 In Japan, a public campaign focusing on stroke symptoms reduced pre-hospital delay but did not increase the proportion of patients treated with IV tPA.16 Predictors of a patient- and pre-hospital delay include severe stroke, lower age and admission by EMS.17,18

In case of suspected LVO, it is more likely that EMS will be notified by a bystander than via initial contact to the primary care physician.19 In an effort to reduce pre- and in-hospital delay, an ambulance fitted with a computed tomography scanner was launched in Berlin.20 IV tPA can thus be given quickly and transportation to a CSC can be initiated more rapidly. This solution is expensive and might only be cost effective in densely populated areas characterised by high stroke rates.21

Pre-hospital scoring systems identifying LVO already exist22,23 but only the rapid arterial occlusion evaluation (RACE) scale24 has been evaluated in the pre-hospital setting. Still, the RACE scale was not valuated in 60% of patients by EMS, possibly because of its complexity. We developed a simpler triage protocol (Table 1) identifying LVO in collaboration with EMS to ensure ease of use, minimal time consumption and the scale’s usefulness over the phone for the dispatcher. After our study was initiated, the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Severity Scale was introduced.25 There are similarities between this scale and ours. One such similarity is the item eye turning as the underlying pathophysiology is an extensive lesion including cortical regions involving the frontal eye field. This scale has not been tested in pre-hospital settings yet. Future studies are necessary to develop and examine which scoring system is the most sensitive for identifying patients with LVO while still being user friendly in the pre-hospital setting.

A quality improvement initiative aiming at reducing door-to-needle time (in-hospital delay) was successful and associated with an increase in the proportion of patients with door-to-needle times of 60 min or less (29.6 to 53.3%), a lower in-hospital mortality, reduced incidence of symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage and an increase in the percentage of AIS patients who were able to be discharged to home.26 In this initiative, one of the strategies during both time periods was pre-notification of the hospital. In our setting, we advocate that informing the entire stroke team that a ‘big stroke’ is arriving be part of the routine practice.

The intervention was focused on the pre-hospital setting, and in-hospital delay was significantly reduced in the post-intervention period. As mentioned, direct transfer to CSC would result in reduction of in-hospital delay, since this delay is measured from admission to the first hospital to final treatment. The CSC has performed EVT since 2004 and since 2010 with 24/7 coverage, so it is unlikely that a training effect reduced in-hospital delay.

An important aspect of our study was its focus on correct selection and visitation of patients with suspected LVO to a CSC. This approach could have prolonged transport (pre-hospital delay) for those patients who needed treatment with IV tPA only if they bypassed a more closely located PSC. However, this was not the case since treatment delay for the IV tPA patients was not changed significantly.

The reduction in system delay for patients undergoing EVT translated into a significantly improved functional outcome at 90 days. This is in line with the results reported in the newly published, successful EVT trials which focused on achieving better outcomes by shortening treatment delay.5,27,28 The findings of these studies all suggest that acceleration of treatment time is essential in gaining a better prognosis. The distance the patients were transported to the first hospital did not seem to change in the post-intervention period, but looking at the map, Figure 1, it can be seen that for many patients the distance to the first hospital is not different, but the bypass patients are saved a long transportation to the CSC after initial admission at the PSC.

An important limitation of our study is the comparison of sequential periods because the two time periods are sensitive to confounders that evolve over time. The procedures related to door-to-needle time are smoothed over time, and that might be part of the reason for the shorter in-house delay that we recorded in the latter time period. We support a randomised approach as seen in cardiology.29 Also, the used questionnaire has not been validated yet, but this is planned as a part of an ongoing project. The available scales were not suitable for use by a dispatcher.

In conclusion, our study provides proof of concept that a triage system designed to identify patients with LVO can shorten system delay for EVT patients significantly, particularly the in-hospital delay, resulting in a better outcome. The study also demonstrates that this can be achieved without increasing delay for the IV tPA group.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was supported by a grant from TrygFonden Denmark. Tryg Fonden Denmark had no influence on the study design, data collection, presentation of data or the conclusions made.

Ethical approval

N/A

Informed consent

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (J. No. 1-16-02-440-13). Ethical approval was waiver since this is not required using register data.

Guarantor

CZS

Contributorship

GA, SPJ, CZS conceived the study. NFM collected data with MR and MSA. NFM drafted the first manuscript with CZS and SH. Statistical analysis was done by NFM and SPJ. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version.

References

- 1.Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The national institute of neurological disorders and stroke rt-pa stroke study group. N Engl J Med 1995; 333: 1581–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saver JL, Fonarow GC, Smith EE, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and outcome from acute ischemic stroke. JAMA 2013; 309: 2480–2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khatri P, Yeatts SD, Mazighi M, et al. Time to angiographic reperfusion and clinical outcome after acute ischaemic stroke: an analysis of data from the interventional management of stroke (IMS iii) phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13: 567–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1019–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatia R, Hill MD, Shobha N, et al. Low rates of acute recanalization with intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in ischemic stroke: real-world experience and a call for action. Stroke 2010; 41: 2254–2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barber PA, Zhang J, Demchuk AM, et al. Why are stroke patients excluded from TPA therapy? An analysis of patient eligibility. Neurology 2001; 56: 1015–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tong D, Reeves MJ, Hernandez AF, et al. Times from symptom onset to hospital arrival in the get with the guidelines—stroke program 2002 to 2009: temporal trends and implications. Stroke 2012; 43: 1912–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fassbender K, Balucani C, Walter S, et al. Streamlining of prehospital stroke management: the golden hour. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 585–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wildenschild C, Mehnert F, Thomsen RW, et al. Registration of acute stroke: validity in the Danish Stroke Registry and the Danish National Registry of Patients. Clin Epidemiol 2014; 6: 27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emberson J, Lees KR, Lyden P, et al. Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet 2014; 384: 1929–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazighi M, Chaudhry SA, Ribo M, et al. Impact of onset-to-reperfusion time on stroke mortality: a collaborative pooled analysis. Circulation 2013; 127: 1980–1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheth SA, Jahan R, Gralla J, et al. Time to endovascular reperfusion and degree of disability in acute stroke. Ann Neurol 2015; 78: 584–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faiz KW, Sundseth A, Thommessen B, et al. Factors related to decision delay in acute stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2014; 23: 534–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harraf F, Sharma AK, Brown MM, et al. A multicentre observational study of presentation and early assessment of acute stroke. BMJ 2002; 325: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishijima H, Kon T, Ueno T, et al. Effect of educational television commercial on pre-hospital delay in patients with ischemic stroke. Neurol Sci 2016; 37: 105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang KC, Tseng MC, Tan TY. Prehospital delay after acute stroke in kaohsiung, taiwan. Stroke 2004; 35: 700–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong ES, Kim SH, Kim WY, et al. Factors associated with prehospital delay in acute stroke. EMJ 2011; 28: 790–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vidale S, Beghi E, Gerardi F, et al. Time to hospital admission and start of treatment in patients with ischemic stroke in northern Italy and predictors of delay. Eur Neurol 2013; 70: 349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebinger M, Winter B, Wendt M, et al. Effect of the use of ambulance-based thrombolysis on time to thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014; 311: 1622–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gyrd-Hansen D, Olsen KR, Bollweg K, et al. Cost-effectiveness estimate of prehospital thrombolysis: results of the phantom-s study. Neurology 2015; 84: 1090–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singer OC, Dvorak F, du Mesnil de Rochemont R, et al. A simple 3-item stroke scale: comparison with the national institutes of health stroke scale and prediction of middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke 2005; 36: 773–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nazliel B, Starkman S, Liebeskind DS, et al. A brief prehospital stroke severity scale identifies ischemic stroke patients harboring persisting large arterial occlusions. Stroke 2008; 39: 2264–2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez de la Ossa N, Carrera D, Gorchs M, et al. Design and validation of a prehospital stroke scale to predict large arterial occlusion: the rapid arterial occlusion evaluation scale. Stroke 2014; 45: 87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz BS, McMullan JT, Sucharew H, et al. Design and validation of a prehospital scale to predict stroke severity: Cincinnati prehospital stroke severity scale. Stroke 2015; 46: 1508–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fonarow GC, Zhao X, Smith EE, et al. Door-to-needle times for tissue plasminogen activator administration and clinical outcomes in acute ischemic stroke before and after a quality improvement initiative. JAMA 2014; 311: 1632–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2365–2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saver JL, Goyal M, Diener HC. Stent-retriever thrombectomy for stroke. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersen HR, Nielsen TT, Rasmussen K, et al. A comparison of coronary angioplasty with fibrinolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]