Abstract

Introduction

Recent studies showed improved patient outcomes with endovascular treatment of acute stroke compared to medical care, including IV rtPA, alone. Seven trials have reported results, each using different clinical and imaging criteria for patient selection. We compared eligibility for different trial protocols to estimate the number of patients eligible for treatment.

Patients and methods

Patient data were extracted from a single centre database that combined patients recruited to three clinical studies, each of which obtained both CTA and CTP within 6 h of stroke onset. The published inclusion and exclusion criteria of seven intervention trials (MR CLEAN, EXTEND–IA, ESCAPE, SWIFT-PRIME, REVASCAT, THERAPY and THRACE) were applied to determine the proportion that would be eligible for each of these studies.

Results

A total of 263 patients was included. Eligibility for IAT in individual trials ranged from 53% to 3% of patients; 17% were eligible for four trials and under 10% for two trials. Only three patients (1%) were eligible for all studies. The most common cause of exclusion was absence of large artery occlusion (LAO) on CTA. When applying simplified criteria requiring an ASPECT score > 6, 16% were eligible for IAT, but potentially 40% of these patients were excluded by perfusion criteria and more than half by common NIHSS thresholds.

Conclusion

Around 15% of patients presenting within 6 h of stroke onset were potentially eligible for IAT, but clinical trial eligibility criteria have much more limited overlap than is commonly assumed and only 1% of patients fulfilled criteria for all recent trials.

Keywords: Ischaemic stroke, acute stroke treatment, mechanical thrombectomy

Introduction

Between December 2014 and April 2015, five clinical trials were published that showed benefit of intra-arterial therapy (IAT), predominantly using stent-retrievers for thrombectomy, in a subset of acute stroke patients with large artery occlusion (LAO), compared with best medical care (including intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (IV rtPA) in the majority).1–5 Two further trials have presented similar findings.6,7 The success of these trials, compared with previous studies of IAT, was attributed to better patient selection (including the use of advanced imaging), streamlined study procedures to achieve rapid revascularisation, and the use of stent retriever devices, capable of producing high rates of recanalisation.8

Introduction of IAT to routine acute stroke care requires re-organisation of stroke services, so that patients most likely to benefit are rapidly directed to centres where endovascular services are available. Each of the published or presented IAT trials used different clinical and imaging criteria for patient selection (summarised in Table 1). While opinion supports the concept that a common group of readily identifiable patients has been studied in all IAT trials,8,9 we hypothesised that if so, then a substantial proportion of patients with acute stroke would be eligible for multiple trial protocols. We tested this by applying trial entry criteria to a database of acute stroke patients, all of whom underwent CT angiography (CTA) and CT perfusion (CTP) in addition to non-contrast CT (NCCT) in the acute stage in order to estimate the number of patients potentially eligible for IAT, and to compare eligibility across different trials.

Table 1.

Clinical and imaging inclusion criteria for seven endovascular treatment trials.

| Clinical criteria |

Patients ineligible for IV rtPA | CTA criteria |

Tissue selection criteria |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Age | Pre-stroke function | Max time from onset to endovascular therapy | NIHSS | Extra-cranial ICA occlusion | Occluded arteries | Baseline NCCT | Perfusion criteria | Collaterals | |

| MRCLEAN1 | ≥18 | Any | 6 h | ≥2 | No | Included | ICA, M1, M2, A1, A2 | Not used for selection | Not used for selection | Not used for selection |

| ESCAPE2 | ≥18 | Barthel index > 90 | 12 h | >5 | Included | Included, except for dissection | ICA, M1, M1 equivalent (two or more M2 occlusions) | ASPECT score > 5 | CBV ASPECT score used with different cut off depending on coverage | Collaterals seen in more than 50% of MCA region by multiphase CTA |

| EXTEND-IA3 | ≥18 | mRS < 2 | 6 h | Any | No | Not included | ICA, M1 or M2 | Hypodensity more than one third of MCA territory | Mismatch ratio > 1.2 Absolute mismatch volume > 10 Core volume < 50 ml | Not used for selection |

| REVASCAT5 | 18–85 | mRS ≤ 1 | 8 h | ≥6 | Included | Included | ICA or M1 | ASPECT > 6 for patients > 80 years ASPECT > 9 for patients aged 81–85 | CBV ASPECT used in patients treated more than 4.5 h from symptom onset | Not used for selection |

| SWIFTPRIME4 | 18–80 | mRS ≤ 1 | 6 h | ≥8–<30 | No | Not included | ICA or M1 | ASPECT > 6 | Used for some patients only Corevolume < 50 ml Total infarct > 100 ml Penumbra volume > 15 ml Mismatch ratio ≥ 1.8 | Not used for selection |

| THRACE6 | 18–80 | Any | 4 h | ≥10–≤25 | No | Not included | ICA, M1, upper third of basilar | Not used for selection | Not used for selection | Not used for selection |

| THERAPY7 | 18–85 | mRS = 0 | Within local thrombolysis window | ≥8 or aphasic | No | Not included | Large artery occlusion in anterior circulation | Hypodensity more than 1/3 of the MCA territory Clot more than 8 mm | Not used for selection | Not used for selection |

MRI-based imaging criteria are not shown.

NIHSS: National Institute of Health Stroke Scale; ICA: internal carotid artery; NCCT: non-contrast CT; mRS: modified Rankin Scale; MCA: middle cerebral artery; ASPECT: Alberta Stroke Programme Early CT; CBV: cerebral blood volume.

Patients and methods

Patient data were extracted from an acute stroke imaging database that combined patients recruited from three acute studies that acquired multimodal CT less than 6 h after symptom onset (the multicentre acute stroke imaging study (MASIS),10 post-stroke hyperglycemia (POSH)11 and Alteplase-Tenecteplase Trial Evaluation for Stroke Thrombolysis (ATTEST)12 studies) at a single centre between 2008 and 2013. Two studies were observational studies evaluating feasibility of complex imaging and the pathophysiology of hyperglycemia, respectively (MASIS and POSH), while the third (ATTEST) compared two different IV thrombolytic agents within 4.5 h of symptom onset. Entry and exclusion criteria are detailed in supplementary material. Endovascular treatment was not undertaken. Clinical details included demographic and risk factor data, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)13 scores at onset and 24 h, estimated pre-morbid modified Rankin Scale (mRS),14 time from symptom onset to CT and to treatment (if applicable). All patients had NCCT, CTP and CTA at presentation. This was performed using a multi-detector Scanner (Philips Brilliance 64 Slice). Whole brain NCCT was acquired first, followed by CTP with 40 mm slab coverage (8 × 5 mm2 slices), using a 50 ml contrast bolus administered at 5 ml/second via a large-gauge peripheral venous cannula. Finally, a CT angiogram was performed from aortic arch to the top of the lateral ventricles using bolus tracking to enable correct timing of image acquisition.

CTP was processed offline with MiStar (Apollo Medical Imaging Technology, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) to produce Cerebral Blood Flow (CBF) and Cerebral Blood Volume (CBV), Delay Time (DT) and Mean Transient Time (MTT) maps. Ischaemic core was defined as tissue with reduced CBF (relative CBF < 40% of contralesional hemisphere) and prolonged delay time (relative DT > 2 s); penumbra volume was defined as tissue with relative DT > 2 s but relative CBF ≥ 40% of contralateral.15 To account for the limited z-axis coverage of CTP, we reduced the 70 ml threshold used by EXTEND-IA16 and DEFUSE-217 proportionately. Details of scan acquisition and processing were previously published.18 We also evaluated baseline NCCT for ASPECT scores.19

The published inclusion and exclusion criteria of seven intervention trials (MR-CLEAN,1 EXTEND–IA,3 ESCAPE,2 SWIFT-PRIME,4,20 REVASCAT,5 THERAPY7 and THRACE6) were applied to determine eligibility for each study. Minor modifications of inclusion criteria were required to match our data set, as detailed in Supplementary material.

Individual trial criteria were applied to each individual case and eligibility for all possible combinations of trial eligibility were tabulated. We compared patient characteristics of the cases selected from our population with those of each trial. Finally, we calculated the number of patients that would be eligible for IAT in a hypothetical clinical setting using simplified eligibility criteria more reflective of clinical practice.

Results

A total of 263 patients were included (60% male, mean age 70.6 years). Clinical features in our patients were comparable with those of patients recruited in the published trials, with the exception of a notably lower median NIHSS score on admission compared with trial populations for EXTEND-IA, SWIFT-Prime and REVASCAT, and a longer median onset to IV rtPA administration time (Table 2 in supplementary material).

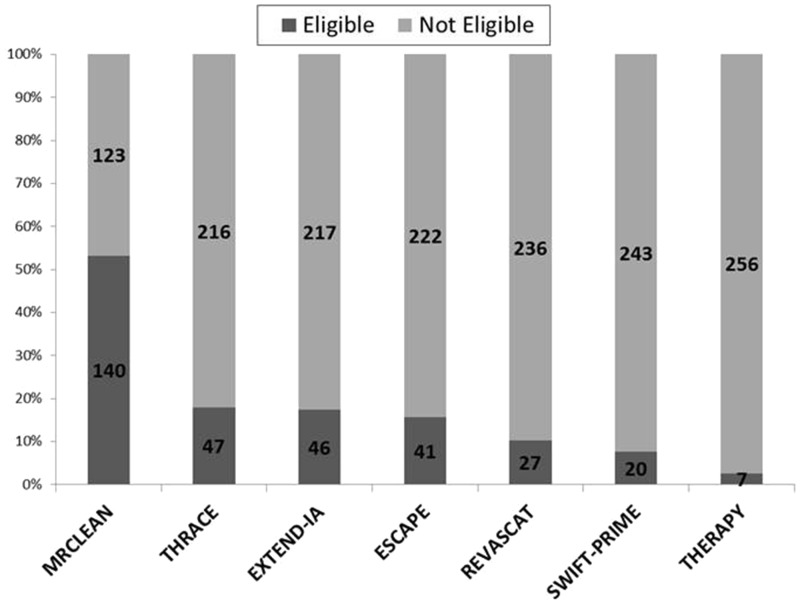

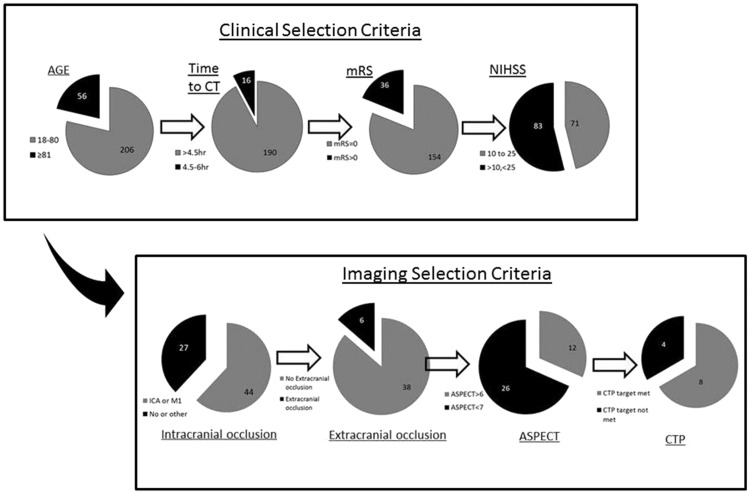

Figure 1 shows the numbers of patients meeting eligibility criteria for each of the seven studies. The widest eligibility criteria identified 53% of patients as potentially eligible for IAT (for MR CLEAN), declining to 3% for the most restrictive (THERAPY). Figure 2 shows the number of patients eligible for different study combinations, and Figure 3 shows the number of patients excluded by applying the most restrictive inclusion criteria sequentially to our patients. Only three patients fulfilled eligibility criteria for all studies. One quarter of the patients excluded based on the narrowest NIHSS range had LAO (Table 1 in supplementary material). The number of patients excluded based on perfusion or ASPECTS selection varied from 24% to 62%, depending on the site of occlusion and the tissue criteria used (Figure 2 in supplementary material).

Figure 1.

The number of patients meeting entry criteria for each of the studies.

Figure 2.

Numbers of patients eligible for different study combinations. MR: MRCLEAN; TH: Thrace; EX: Extend-IA; ES: ESCAPE RE: REVASCAT; SP: SWIFT-PRIME; TY: Therapy.

Figure 3.

Number eligible to all studies after applying different clinical and imaging selection criteria. The top panel shows sequential exclusion of patients based on clinical criteria, while the bottom panel shows sequential exclusion of patients based on imaging criteria. Of the eight patients meeting CTP target criteria, only three had a visible clot more than 8 mm, one of the eligibility criteria of THERAPY trial.

Figure 4 shows the selection process in a hypothetical clinical setting. Using two simple imaging criteria for patient selection, presence of LAO and ASPECT score > 6, 16% of patients would be considered for IAT. The numbers would be reduced further if selection was restricted by onset to treatment time, NIHSS thresholds or the use of CTP.

Figure 4.

Number of patients with selected for IAT in a hypothetical clinical setting.

Discussion

Recently published studies have shown that IAT improves outcome in selected patients with large artery occlusive stroke, predominantly as an adjunct to IV rtPA. Since all individual trials were small or modest in size, conducted at highly experienced acute stroke centres, and with somewhat different eligibility criteria, it is important to establish the comparability of populations across different trials, both for data pooling and for service planning. Recent group-level meta-analysis identified significant heterogeneity among published trials.21 When applied to a population of acute stroke patients presenting within 6 h of symptom onset and with advanced imaging available, but otherwise minimally selected, we found that the number of patients eligible for the different studies individually ranged between 3% and 53% of all patients in our database, and for all trial protocols except MR CLEAN was < 20%. Only 14% would have been eligible for three or more of the recent trials.

The most important clinical selection criterion is the NIHSS score, excluding more than 50% of patients when the narrowest range is applied. Previous studies suggested NIHSS score thresholds above 7–10 to be associated with higher probability of LAO.22,23 Since any given NIHSS threshold has limited positive predictive value,24,25 however, trials will inevitably arbitrarily restrict recruitment of angiographically appropriate patients by setting NIHSS thresholds. The median NIHSS of patients treated by IAT in published studies was 17, regardless of the pre-specified threshold in protocol inclusion and exclusion criteria. When the same selection criteria were applied to our patients, the median NIHSS varied from 11.5 to 16. When applying the clinical selection criteria of MR CLEAN, EXTEND-IA and ESCAPE to our patients, a larger proportion had an M2 occlusion. The lower median NIHSS in our less selected population raises the possibility of additional differences in patient selection processes in published trials that are not evident from trial protocol eligibility alone. The unavailability of trial screening log data for the majority of studies published to date limits our ability to determine whether additional, non-protocol exclusion criteria were applied.

Imaging selection criteria varied among the different studies. Non-invasive imaging of the intracranial circulation, mostly using CTA, was a minimum requirement in all studies. MR CLEAN and THRACE did not specify any additional imaging in patient selection, while all other studies used NCCT criteria to exclude patients with large infarct core. The use of CTP varied: EXTEND-IA used CTP as the major tissue imaging selection method, while its use in SWIFT PRIME, REVASCAT and ESCAPE was variable. It should be noted that CTP was also obtained in a large proportion (66%) of MR CLEAN patients, but was not deployed to influence patient selection or treatment decisions.

About half of our patients were ineligible due to absence of a major vessel occlusion, which is similar to the finding in EXTEND-IA. The number of patients excluded based on additional parenchymal tissue selection criteria in our sample, however, was significantly larger than the 25% reported by the EXTEND IA investigators,3 different trial protocols excluding between 36 and 64% of patients with ICA or M1 occlusion. This may be a consequence of the later presentation times in our population, with onset to IV rtPA treatment times of around 180 min in our population compared with 85–120 min in the trial populations. It is clear that different tissue based selection criteria result in large differences in the population selected, with SWIFT-Prime criteria excluding many more patients than EXTEND-IA criteria. Individual workflow variations make definitive estimates of the impact of different imaging criteria difficult: for example, if NCCT ASPECT score is applied before knowing a CTA result, a different group is excluded compared with applying an ASPECT score to the group with eligible LAO on CTA.

Our study has limitations. We cannot provide a population-based estimate of the proportion eligible, but this was not our goal: rather, we were interested to assess the comparability of the different imaging selection strategies. Our study populations were not highly selected, predominantly including observational data from patients within 6 h of symptom onset and applying no exclusions except fitness for follow-up and absence of contraindications to IV contrast administration. The ATTEST trial population (comprising 38% of those included here) required additional eligibility for IV thrombolysis. While our populations closely resembled those reported in the IAT trials, we cannot exclude the possible influence of selection biases in our original study populations influencing the findings. The MR CLEAN trial elected to use wide clinical inclusion criteria, and no formal tissue imaging criteria, and consequently the majority of our patients would have been eligible for this protocol: the characteristics of our eligible patients correspond closely to the MR CLEAN IAT group, with the exception of longer onset to IV rtPA initiation.

Clinical trial inclusion and exclusion criteria are generally designed to optimise trial efficiency, selecting a responder population in order to maximise the treatment effect size and thus minimise the sample size. Recognising that this inevitably differs from clinical practice, where less restrictive criteria are likely to be employed, we explored a simplified set of selection criteria using only presence of LAO and small core (operationalised as ASPECTS > 6), but even in this setting, only 16% of patients would be eligible before applying any clinical or tissue selection criteria. Our data do not allow any conclusions about the preferred imaging strategy that would provide the best cost–benefit balance, which will require health economic analyses taking into account key infrastructure available in each region. Such economic analyses should take into consideration the wide variation in requirements for patient transfer and imaging that are implied by our findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is likely that around 15% of patients presenting within 6 h of symptom onset and suitable for imaging selection are potentially eligible for IAT, but additional clinical or imaging selection criteria exclude a widely varying proportion of these patients. The assumption that a common clinical population would be identified despite different trial selection processes does not appear to be supported from our data,26 with large differences in those excluded by different criteria, and strikingly only 1% of patients meeting all trial protocols.

Supplementary Material

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. However, the original studies were supported by the Translational Medicine Research Initiative and the Stroke Association, grants TSA 2006/03, TSA 2006/11 and TSA 2010/04.

Ethical approval

Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before participation in original studies.

Guarantor

KM.

Contributorship

KM is responsible for study conception and design; SET, BC, XH, FM, DK, NM and FM contributed to data collection and analysis; SET performed statistical analysis and wrote the first draft. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. New Engl J Med 2015; 372: 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. New Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1019–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. New Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1009–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, et al. Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA alone in stroke. New Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2285–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E, et al. Thrombectomy within 8 hours after symptom onset in ischemic stroke. New Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2296–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bracard S, Ducrocq X and Guillemin F. THRACE study: intermediate analysis results. Int J Stroke 2015; 10(suppl S2): 31.

- 7.Mocco J, Zaidat O and von Kummer R. Results of the therapy trial: a prospective, randomized trial to define the role of mechanical thrombectomy as adjunctive treatment to iv RTPA in acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke 2015; 10(suppl S2): 10.

- 8.Pierot L, Derdeyn C. Interventionalist perspective on the new endovascular trials. Stroke 2015; 46: 1440–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hacke W. The results of the recent thrombectomy trials may influence stroke care delivery: are you ready? Int J Stroke 2015; 10: 646–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wardlaw JM, Muir KW, Macleod MJ, et al. Clinical relevance and practical implications of trials of perfusion and angiographic imaging in patients with acute ischaemic stroke: a multicentre cohort imaging study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013; 84: 1001–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacDougall NJ, McVerry F, Huang X, et al. Post-stroke hyperglycaemia is associated with adverse evolution of acute ischaemic injury. Cerebrovasc Dis 2014; 37(Suppl 1): 267. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang X, Cheripelli BK, Lloyd SM, et al. Alteplase versus tenecteplase for thrombolysis after ischaemic stroke (ATTEST): a phase 2, randomised, open-label, blinded endpoint study. Lancet Neurol 2015; 14: 368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brott T, Adams HP, Jr, Olinger CP, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke 1989; 20: 864–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, et al. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 1988; 19: 604–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bivard A, Spratt N, Levi C, et al. Perfusion computer tomography: imaging and clinical validation in acute ischaemic stroke. Brain 2011; 134: 3408–3416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. New Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1009–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lansberg MG, Straka M, Kemp S, et al. MRI profile and response to endovascular reperfusion after stroke (DEFUSE 2): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2012; 11: 860–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheripelli BK, Huang X, MacIsaac R, et al. Interaction of recanalization, intracerebral hemorrhage, and cerebral edema after intravenous thrombolysis. Stroke 2016; 47: 1761–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barber PA, Demchuk AM, Zhang JJ, et al. Validity and reliability of a quantitative computed tomography score in predicting outcome of hyperacute stroke before thrombolytic therapy. Lancet 2000; 355: 1670–1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, et al. Solitaire with the Intention for Thrombectomy as Primary Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke (SWIFT PRIME) trial: protocol for a randomized, controlled, multicenter study comparing the Solitaire revascularization device with IV tPA with IV tPA alone in acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke 2015; 10: 439–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badhiwala JH, Nassiri F, Alhazzani W, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: A meta-analysis. JAMA 2015; 314: 1832–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olavarria VV, Delgado I, Hoppe A, et al. Validity of the NIHSS in predicting arterial occlusion in cerebral infarction is time-dependent. Neurology 2011; 76: 62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heldner MR, Zubler C, Mattle HP, et al. National Institutes of Health stroke scale score and vessel occlusion in 2152 patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2013; 44: 1153–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maas MB, Furie KL, Lev MH, et al. National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score is poorly predictive of proximal occlusion in acute cerebral ischemia. Stroke 2009; 40: 2988–2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooray C, Fekete K, Mikulik R, et al. Threshold for NIH stroke scale in predicting vessel occlusion and functional outcome after stroke thrombolysis. Int J Stroke 2015; 10: 822–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eastwood JD, Lev MH, Wintermark M, et al. Correlation of early dynamic CT perfusion imaging with whole-brain MR diffusion and perfusion imaging in acute hemispheric stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003; 24: 1869–1875. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.