Abstract

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is an autosomal dominant cancer-predisposing condition characterised by intestinal hamartomatous polyps and distinct melanin depositions in skin and mucosa. Small intestinal cancer in patients with PJS usually presents by the third decade. A 7-year-old-PJS boy presented with recurrent episodes of colicky abdominal pain and melena requiring repeated blood transfusions. Abdominal CT scan revealed multiple jejunal polyps with jejunoileal intussusception. On exploration, the intussuscepted bowel was resected along with its mesentery and anastomosed. Simultaneously, multiple enterotomies with resection of palpable polyps were performed. The resected bowel showed well-differentiated stage 2A adenocarcinoma with clear resected margins. Postoperatively, the complaints were relieved. On follow-up, he was asymptomatic and is now on yearly cancer surveillance. This is probably the youngest reported case of small bowel cancer in PJS.

Keywords: gi bleeding, small intestine, small intestine cancer, gastrointestinal surgery, paediatric surgery

Background

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is an autosomal dominant cancer-predisposing genetic disorder characterised by intestinal hamartomatous polyps and a distinct macular melanin deposition in skin and mucosa. The median time of first presentation with polyps is 13 years.1 Patients usually present with crampy abdominal pain related to transient intussusception or anaemia due to occult blood loss. The cumulative risk of developing small intestine cancer in patients with PJS is 13% and the mean age of diagnosis is 41.7±17.5 years.2 The risks among patients with PJS for developing any first cancer by ages 20, 30, 40, 50, 60 and 70 years are 2%, 5%, 17%, 31%, 60% and 85%, respectively.2 In the paediatric PJS population, small bowel surveillance is done to evaluate the risk of obstruction rather than to identify small bowel malignancy which is thought to arise in adulthood. According to the current guidelines, tumour screening is not regularly initiated until after the age of 18 years.3

We, herein, report a case of probably the earliest onset of small bowel adenocarcinoma in a 7-year-old PJS boy, an observation which might have bearing on the current screening guidelines.

Case presentation

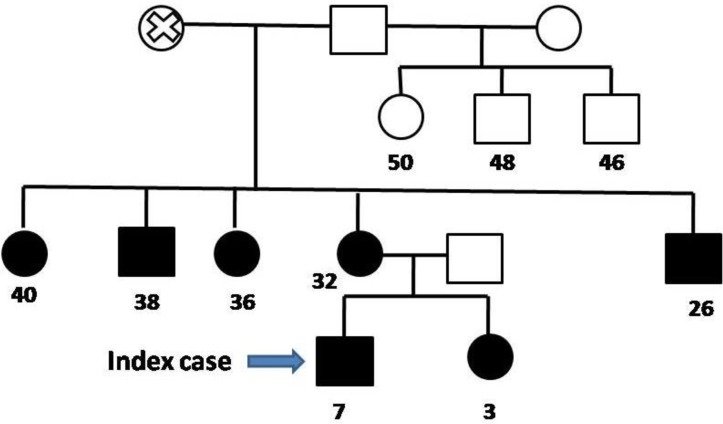

A 7-year-old boy, diagnosed case of PJS, presented with colicky abdominal pain and bleeding per rectum for 2 days. He had a history of recurrent episodes of melena leading to severe anaemia requiring multiple blood transfusions in the past. He also had a history of colonoscopy, upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy and polypectomy done twice. His grandmother, mother, younger sister and four other relatives had PJS as detailed in the family tree (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Family tree with autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. Square represents male and circle refers to female. Completely coloured shape refers to those affected with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Cross represents dead. Age in years given below each of those affected by the disease.

On examination, he had multiple hyperpigmented melanotic macules on the lips, buccal mucosa and his finger tips (figure 2). He had tachycardia with a pulse rate of 112/min and looked pale. His abdomen was distended with guarding and tenderness in the right upper quadrant.

Figure 2.

Characteristic melanin pigmentation observed over the finger tips and hands of the child.

Investigations

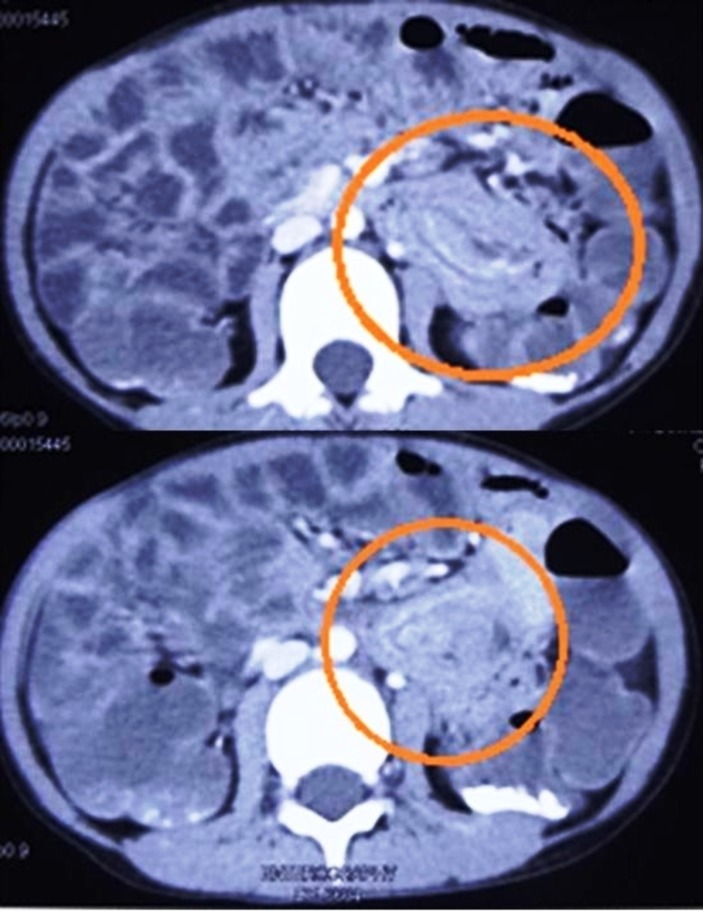

His haemoglobin was 7.1 g/dL. The X-ray (abdomen) was suggestive of small bowel obstruction. On an ultrasound scan, intussusception was suspected. This was confirmed on abdominal CT scan which also revealed multiple small intestinal polyps extending from the jejunum to the ileocaecal junction with jejunoileal intussusception (figure 3).

Figure 3.

CT scan of the abdomen showing multiple small intestinal polyps and a segment of jejunoileal intussusception.

Treatment

After adequate resuscitation, he underwent emergency laparotomy. On exploration a mid-jejunoileal intussusception was found. The intussusceptum was partially reduced and the remaining jejunojejunal intussuscepted segment along with its mesentery was resected (total length 10 cm) and an end-to-end anastomosis done. Multiple large palpable polyps were removed by selective enterotomies and repaired along the entire small bowel (figure 4). There were no enlarged lymph nodes seen.

Figure 4.

(A) Partial manual reduction of the intussusceptions done, rest of the segment resected and anastomosed. (B) Specimen retrieval after multiple enterotomies and polypectomies.

Outcome and follow-up

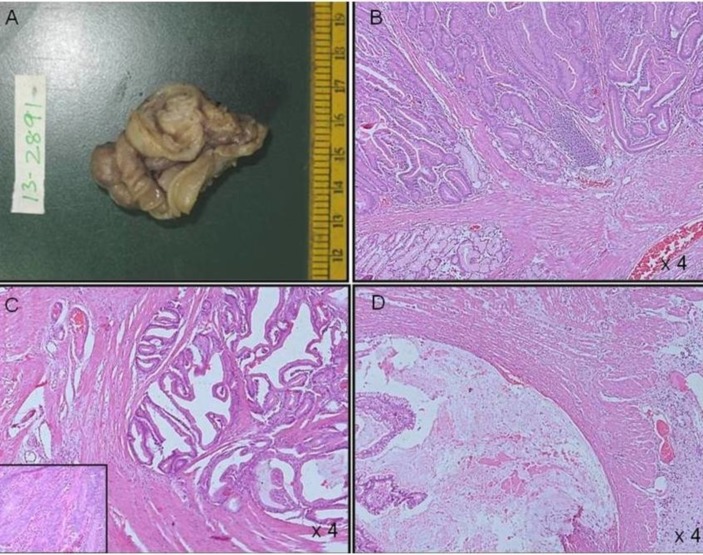

The child tolerated enteral feeds from the fourth postoperative day and was discharged on the eighth day. The histology of the isolated resected polyps showed hamartomatous polyps. The resected intussuscepted bowel segment, however, showed features suggestive of adenocarcinoma stage 2A, that is, invasion of dysplastic glands into the muscle layer with glandular epithelium showing features of high-grade dysplasia (figure 5). The resected margins were free of tumour. The mesenteric lymph nodes (16) were all negative for adenocarcinoma. There was no evidence of distant metastasis. Hence, tumour was stage 2A (T3, N0, M0). No further chemotherapy or radiotherapy was required.

Figure 5.

(A) Segment of small intestine with polyp. (B) Smaller separately lying polyps show typical features of a hamartomatous polyp with arborising smooth muscle. (C) Carcinomatous areas show invasion of dysplastic glands in to the muscle layer with glandular epithelium showing features of high-grade dysplasia (inset) along with, (D) dissecting type of extracellular mucin extending to the serosal layer.

On follow-up at 1 year, the child was asymptomatic. He underwent colonoscopy, upper GI endoscopy and ultrasound of abdomen and scrotum after 6 months of surgery and no abnormal or suspicious findings were reported. He is on annual surveillance and undergoes colonoscopy and upper GI endoscopy for the same. The sequence analysis of the STK11 gene did not show heterozygous mutation found in 30%–70% of PJS cases. The family refused consent for further screening investigations and genetic testing of other affected family members.

Discussion

Diagnostic criteria for PJS

PJS is an autosomal dominant cancer-predisposing syndrome. The diagnostic criteria are based on the clinical findings, and require the presence of hamartomas and any two of the following: (1) family history of PJS, (2) mucocutaneous hyperpigmentation and (3) small bowel polyposis.1 Our patient had all three of the above.

PJS and the risk for developing GI cancers

In PJS, there is an age-dependent risk of developing malignancy. The various GI cancers PJS predisposes to include small intestinal, colonic, rectal, pancreatic and hepatobiliary tract carcinomas which generally occur after the second decade of life.4 The risk of developing GI cancers at ages 30, 40, 50 and 60 years is 1%, 9%, 15% and 33%, respectively.2 Paediatric patients with PJS present with earlier onset of GI-related complications like a prolapsed polyp or intussusception and rarely with small bowel carcinoma.5–9 Small bowel adenocarcinoma in children as such is a very rare disease.10 In PJS, the cumulative risk of small bowel adenocarcinoma is 13% before the age of 64 years.4

Screening in patients with PJS

Screening guidelines have been formed to detect these complications early in paediatric patients with PJS.3 11 The current recommendations for PJS surveillance suggest an initial endoscopy at 8 years of age and then at 18 years followed by every 2–3 years.3 11 PJS children have a significant risk of intussusception due to multiple polyps and a subsequent risk of obstruction.12 Thus, an initial endoscopy is recommended to prevent emergency laparotomy in such patients. Our patient developed adenocarcinoma at probably the youngest reported age of 7 years which suggests that an earlier initiation for cancer screening might be required in some paediatric patients with PJS who share a common risk factor like a particular gene mutation leading to an early development of bowel adenocarcinoma. The risk factor although remains to be identified.

Small bowel cancer in paediatric patients with PJS

A similar case of mucinous adenocarcinoma postresection for lead point jejunojejunal intussusception was reported in a 13-year-old boy with PJS.5 Another case of well-differentiated colon cancer was reported in a 10-year-old PJS girl who underwent repeated surgeries. Her first surgery was for an intussusception which was resected. She was later operated for a perforated colonic mass which turned out to be an adenocarcinoma.6 She eventually succumbed to airway obstruction caused by a mediastinal mass.6 Such case reports (table 1) including ours although scattered do emphasise the need to look into feasibility for an earlier initiation of tumour screening in paediatric patients with PJS, even earlier than the age of 12–15 years. The latest surveillance guidelines by Achatz et al 9 recommend upper GI endoscopy, video capsule endoscopy and colonoscopy at 8 years of age or sooner if symptomatic, although Goldstein and Hoffenberg recommended starting it as early as 4–5 years of age.7 In their study, 40% of the paediatric patients with PJS had already developed complications by the age of 8 years, including intussusception, rectal bleeding, prolapsed rectal polyp and Sertoli cell tumour. Hence, they too emphasised the need for early screening recommendations in paediatric patients with PJS. This should be supplemented by a regular 2–3 yearly upper GI endoscopy, colonoscopy and contrast studies for follow-up.

Table 1.

Case reports of patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome with small intestinal carcinoma presenting in early childhood

| Authors | Age (years)/sex (M=Male; F=Female) | Clinical presentation | Management | Histology | Follow-up | Surveillance |

| Wangler et al 5 | 13/M | Small bowel intussusception. | Emergency laparotomy+resection and anastomosis of the intussuscepted small bowel. | Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma Tumour stage 2a (T3, N0, M0). |

Reresection with 10 cm free margin and expanded lymph node (LN) sampling. | Capsule endoscopy every 2 years. |

| Saranrittichai6 | 10/F | Intussusception Peritonitis. |

Manual reduction by laparotomy. Presented again with peritonitis. Laparotomy colonic mass for which resection and end-to-end anastomosis was done. | Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma invading muscular wall. Two regional LN showed metastatic adenocarcinoma. | Sudden death due to airway obstruction caused by mediastinal mass. | |

| Khanna et al (2018) | 7/M | Small bowel intussusception. | Exploratory laparotomy+partial manual reduction+resection and end-to-end anastomosis of 10 cm bowel segment+multiple enterotomies and polyp removal. | Intussuscepted segment polyp shows adenocarcinoma, stage 2a (T3, N0, M0) with clear resected margins. | Asymptomatic after 6 months of surgery. | Yearly colonoscopy, upper GI endoscopy and USG of abdomen and scrotum. |

GI, gastrointestinal; USG, ultrasound.

Benefits of surveillance and treatment in patients with PJS

A group from UK studied 63 patients with PJS, of which 28 patients had undergone one or more surveillance endoscopies by the age of 18 years.13 Seventeen were found to have developed significant gastroduodenal or colonic polyps. Due to the various surveillance GI investigations, 77 surgical interventions were done in this cohort. None of the histology reported adenocarcinoma. They proposed that ‘if GI cancers do arise through a hamartoma-carcinoma pathway, then polypectomy would prevent cancer formation, in a manner analogous to sporadic colorectal adenomatous polyps’. The lack of luminal GI cancers therefore highlighted the intriguing possibility that surveillance and polypectomy prevented GI cancer development in their patients with PJS.13

Most cases with small intestinal polyps present with intussusception at a median age of 16 years (range 3–50 years).14 Half of those present by the age of 20 years. Clearing of all polyps is preferable but not always possible.8 It has been suggested that when small bowel intussusception occurs, surgery is often necessary and should include careful examination of the entire small bowel to eliminate all significant polyps. In case of a bowel adenocarcinoma, tumour-free margins with mesenteric and lymph node resection should be the intent. Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy has no role if there is no evidence of nodal or distant metastasis.5 In our case too an attempt was made to remove all the palpable polyps through multiple small bowel enterotomies. Though malignancy was not suspected intraoperatively in our case, the resected specimen margins were reported free from tumour. The purpose of reporting this case is to highlight that there is a chance of developing cancer even at younger ages in patients with PJS and whenever an opportunity is available to investigate a patient with PJS, one must be cautious of this fact and do the investigation thoroughly.

Conclusion

We support that a regular GI surveillance could be started early in patients with PJS. This would first reduce the number of emergency laparotomies; second prevent multiple surgical interventions and the risk of short bowel syndrome in the lifetime of patient with PJS and third, timely polypectomy may altogether prevent the development of bowel cancer in few of these patients. The appropriate modality for small bowel surveillance like endoscopy, video capsule endoscopy, barium follow through/enema studies, CT and MRI enterography and enteroclysis can be decided depending on the availability, accessibility and feasibility of the procedure in a particular set-up.15

Learning points.

In case a child with melanotic mucocutaneous pigmented spots presents with small bowel intussusception, one must always consider the diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS).

Dysplastic changes in hamartomatous polyps may take place as early as 7 years of age.

The screening and surveillance for gastrointestinal polyps in paediatric PJS population may be initiated even earlier than the recommended 8 years of age.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Contributors: The patient was admitted under the care of VB. The child was operated and followed up by VB and VK. The manuscript was proposed and drafted by KK and VK. The final revised and corrected manuscript was approved by all authors before submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. McGarrity TJ, Amos C. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: clinicopathology and molecular alterations. Cell Mol Life Sci 2006;63:2135–44. 10.1007/s00018-006-6080-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hearle N, Schumacher V, Menko FH, et al. . Frequency and spectrum of cancers in the Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12:3209–15. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Giardiello FM, Trimbath JD. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and management recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:408–15. 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Giardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Tersmette AC, et al. . Very high risk of cancer in familial Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology 2000;119:1447–53. 10.1053/gast.2000.20228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wangler MF, Chavan R, Hicks MJ, et al. . Unusually early presentation of small-bowel adenocarcinoma in a patient with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2013;35:323–8. 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318282db11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saranrittichai S. Peutz-jeghers syndrome and colon cancer in a 10-year-old girl: implications for when and how to start screening? Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2008;9:159–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goldstein SA, Hoffenberg EJ. Peutz-Jegher syndrome in childhood: need for updated recommendations? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013;56:191–5. 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318271643c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Syngal S, Brand RE, Church JM, et al. . ACG clinical guideline: genetic testing and management of hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:223–62. 10.1038/ajg.2014.435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Achatz MI, Porter CC, Brugières L, et al. . Cancer screening recommendations and clinical management of inherited gastrointestinal cancer syndromes in childhood. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:e107–e114. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blumer SL, Anupindi SA, Adamson PC, et al. . Sporadic adenocarcinoma of the colon in children: case series and review of the literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:e137–41. 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3182467f3e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. . Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut 2010;59:975–86. 10.1136/gut.2009.198499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hinds R, Philp C, Hyer W, et al. . Complications of childhood Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: implications for pediatric screening. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2004;39:219–20. 10.1097/00005176-200408000-00027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Latchford AR, Neale K, Phillips RK, et al. . Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: intriguing suggestion of gastrointestinal cancer prevention from surveillance. Dis Colon Rectum 2011;54:1547–51. 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318233a11f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Lier MG, Wagner A, Mathus-Vliegen EM, et al. . High cancer risk in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and surveillance recommendations. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:1258–64. author reply 1265 10.1038/ajg.2009.725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shenoy S. Genetic risks and familial associations of small bowel carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2016;8:509–19. 10.4251/wjgo.v8.i6.509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]