Abstract

A premature twin infant girl was transferred to a level IV neonatal intensive care unit for recurrent bloody stools, anaemia and discomfort with feeds; without radiographic evidence of necrotising enterocolitis. Additional imaging after transfer revealed a large retroperitoneal mass in the region of the pancreas compressing the inferior vena cava and abdominal aorta, raising suspicion for neuroblastoma. Abdominal exploration and biopsy unexpectedly revealed that the lesion was an infantile capillary haemangioma involving the small bowel, omentum, mesentery and pancreas. The infant was subsequently treated with propranolol, with a decrease in the size of the lesion over the first year of her life and a drastic improvement in feeding tolerance. While cutaneous infantile haemangiomas are common, visceral infantile haemangiomas are less so and may present a significant diagnostic challenge for clinicians. This interesting case demonstrates that such lesions should be considered in the differential diagnosis for unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding or abdominal symptoms in newborns.

Keywords: neonatal intensive care, paediatric surgery

Background

Haemangiomas are the most common benign tumours in infants, affecting 5%–10% of children in this age group.1 2 These lesions are more commonly found in infants who are female, white (non-Hispanic), premature and/or the product of a multiple gestation. The majority of infantile haemangiomas (IH) are isolated cutaneous lesions and do not require any treatment. Less frequently, IHs are found in extracutaneous locations; the liver is the most common extracutaneous site, while the central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract may also be involved.3 Visceral IHs may lead to significant clinical symptoms, including high-output cardiac failure, gastrointestinal bleeding or consumptive hypothyroidism.2 4–6 IHs are typically not present at birth, but appear within the first few weeks of life; their natural history consists of a period of rapid growth within the first several months, followed by a period of relative stabilisation. Spontaneous regression and involution over the course of several months or years is expected,7 and can be hastened by treatment with propranolol.

We present a case of a premature female twin with recurrent bloody stools and feeding intolerance who was diagnosed with a large visceral IH. She was treated with propranolol, had a decrease in the size of her lesion and tolerated advancement to full feeds. Her presentation and clinical workup were a diagnostic challenge for the medical team, and reinforce the utility of abdominal exploration and biopsy when a diagnosis is unclear.

Case presentation

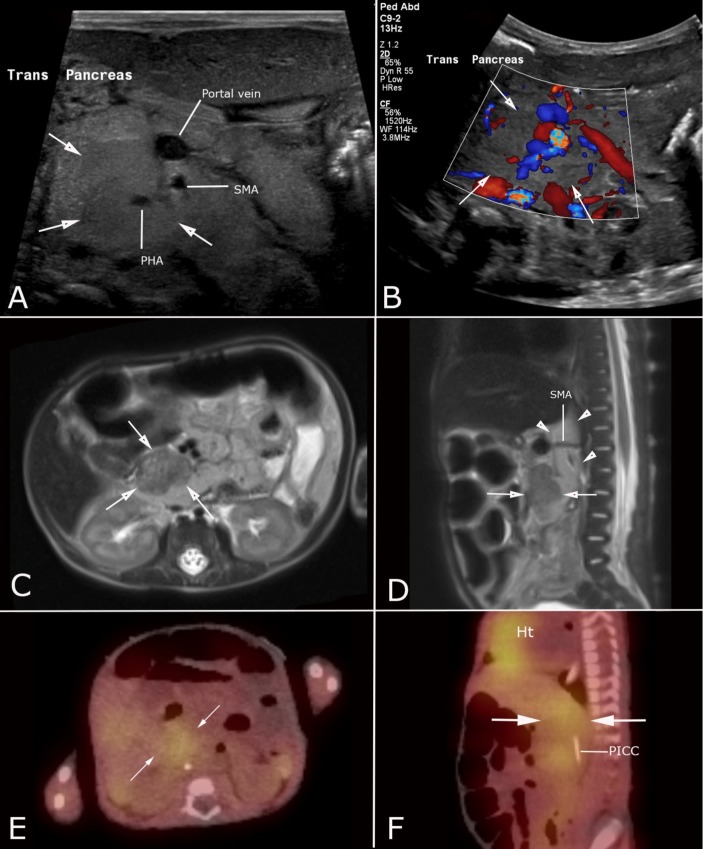

A 7-week-old, former 30-week premature twin girl was transferred to a level IV neonatal intensive care unit after several episodes of feeding intolerance, abdominal distension and bloody stools. She had received antibiotics for presumed necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) due to these symptoms on two occasions prior to transfer, without clear radiographic evidence of this diagnosis. Several abdominal radiographs at the referring hospital and repeat films on arrival showed mildly dilated loops of bowel with evidence of bowel wall thickening; no pneumatosis, free air or portal venous gas was seen. She had required multiple red blood cell transfusions throughout her stay at the referring hospital due to anaemia of unclear aetiology. An ultrasound was obtained after transfer, revealing a mildly hypoechoic, vascular, solid mass-like lesion within the head of the pancreas (figure 1A,B); abdominal CT scan with contrast confirmed an ill-defined retroperitoneal mass in the region of the pancreatic head, compressing the inferior vena cava and abdominal aorta. Based on the patient’s age and the location of the lesion, neuroblastoma was considered the most likely diagnosis, though pancreaticoblastoma and rhabdomyosarcoma were also considered. Laboratory testing revealed mild elevations in vanillylmandelic acid (24 ng/mL; normal <20) and homovanillic acid (60 ng/mL; normal <30), also concerning for neuroblastoma.

Figure 1.

Imaging of a visceral infantile haemangioma mimicking neuroblastoma in a 7-month-old female twin. Greyscale (A) and colour Doppler (B) ultrasound show a mildly hypoechoic, vascular solid mass within the head of the pancreas (white arrows). Axial (C) and sagittal (D) single-shot fast spin echo T2-weighted MR images (C) demonstrate a homogenous hypointense mass within the head of the pancreas (white arrows), in addition to ill-defined retroperitoneal tissue wrapping around the superior mesenteric artery (white arrowheads). Fused single-photon emission CT imaging using 123-iodine (123-I) metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) in axial (E) and sagittal (F) planes shows vague radiotracer uptake in the retroperitoneum (white arrows) corresponding to the abnormal tissue found on ultrasound and MRI. Note the normal MIBG uptake in the heart (Ht). PHA, proper hepatic artery; PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; SMA, superior mesenteric artery.

Contrast-enhanced MRI further demonstrated a discrete mass in the region of the pancreatic head and a more infiltrative abnormality in the retroperitoneum wrapping around the superior mesenteric artery, encasing both the abdominal aorta and the pancreatic head mass (figure 1C,D). Given the more extensive appearance of this lesion on MRI, the differential diagnosis was expanded to include a vascular anomaly. A nuclear medicine scan using 123-iodine metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) was obtained, showing mildly increased radiotracer uptake in the region of the pancreatic head, further supporting the favoured diagnosis of neuroblastoma (figure 1E,F).

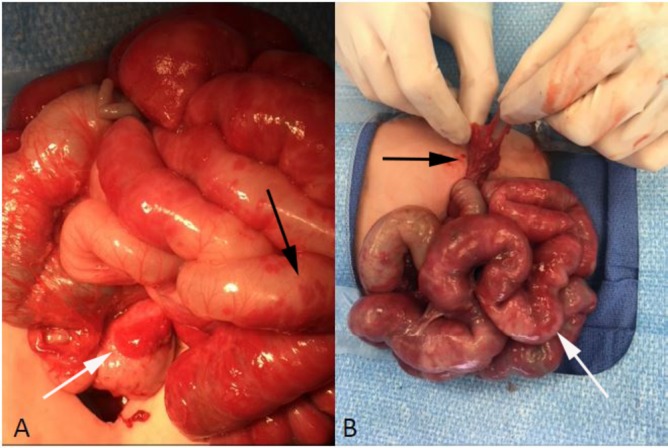

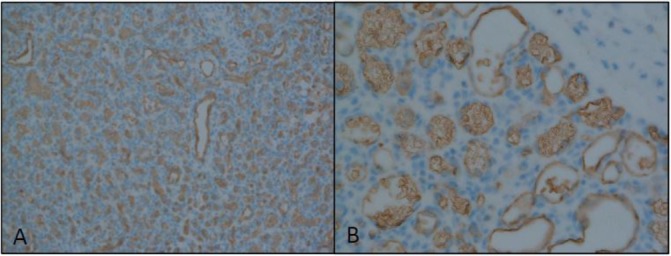

The infant underwent an exploratory laparotomy to obtain a tissue diagnosis. An erythematous nodule was found abutting the head of the pancreas (figure 2A, white arrow), and there was erythematous, rubbery nodularity throughout the omentum (figure 2B, black arrow), small bowel mesentery, and extending up onto the small bowel wall (figure 2A, black arrow and figure 2B, white arrow). Omentectomy and incisional biopsies of the pancreatic head nodule and a mesenteric nodule were performed. Histologic analysis of all specimens revealed lobular proliferation of small vessels, consistent with a capillary IH. This diagnosis was confirmed by immunohistochemical staining for glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1, figure 3A,B).

Figure 2.

Intraoperative photographs of the visceral infantile haemangioma. (A) Erythematous nodule (haemangioma) abutting the head of the pancreas (white arrow) with diffuse erythematous nodularity noted on the bowel wall (black arrow). (B) Erythematous nodularity involving the omentum (black arrow) and small bowel (white arrow).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical staining for glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1) at (A) low power and (B) high power. (Histopathology courtesy of Cristina Pacheco, MD, Department of Pathology, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, Washington).

Propranolol treatment was initiated to hasten involution of her visceral IH, with doses gradually increased over the course of the first postoperative week to a goal of 3 mg/kg/day, which she tolerated well. Prior to starting propranolol, she was found to have mild hypothyroidism, with an elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone of 58.10 mcIU/mL, and was started on levothyroxine. During the first 2 postoperative weeks, enteral feeds were slowly introduced. She was advanced to full enteral feeds and was discharged home on postoperative day 56.

Outcome and follow-up

Over the ensuing 15 months since hospital discharge, the infant has remained asymptomatic, tolerating full enteral feeds without any episodes of haematochezia or melena. She continues to grow well and the pancreatic portion of the IH has decreased in size by ultrasound assessment. She weaned off her propranolol therapy by 13 months of age, though continues to wean off of thyroid hormone replacement.

Discussion

While the diagnosis of cutaneous IH is common in premature infants, this infant with clinical features more typical of NEC and imaging findings most consistent with neuroblastoma is an interesting example of an unexpected diagnosis. Visceral IH is a rare diagnosis, but should be considered in the differential diagnosis of unexplained lower gastrointestinal bleeding in neonates. Due to the potentially infiltrative nature of these lesions, the diagnosis may not be apparent on imaging and may require histologic diagnosis.

Gastrointestinal tract IHs often go unrecognised until they cause clinical symptoms, especially when there is no cutaneous involvement. Symptoms may include gastrointestinal bleeding or feeding intolerance, and may mimic NEC.6 Imaging modalities such as ultrasound and MRI may demonstrate a mass, but there are no clear imaging characteristics of intestinal IHs as there are for IHs in the liver, thus histologic evaluation may be required to make the diagnosis. The proliferating cells within IHs express GLUT-1; immunohistochemical staining for this transporter distinguishes IHs from other vascular lesions.8

The IH described in this report also demonstrated MIBG uptake, further confusing the diagnosis. MIBG is a macromolecule labelled with radioactive 123-iodine or 131-iodine, and is used to visualise neuroendocrine tumours such as neuroblastomas, pheochromocytomas, paragangliomas, carcinoid tumours and medullary thyroid carcinomas.9 MIBG is actively taken up by neuroendocrine cells via the norepinephrine transporter and stored in neurosecretory granules, concentrating the radiotracer. False-positive cases are uncommon, though a few case reports describing MIBG uptake by vascular anomalies containing capillary and venous components have been published.10–13 A compelling explanation for this uptake is provided by Rottenburger et al, who propose that mast cell infiltration of IHs and the expression of vesicular monoamine transporters 2 (VMAT2) by mast cells allows for MIBG accumulation, since MIBG is a substrate of VMAT2.12 Mast cell infiltration was not seen histologically in our patient’s visceral IH, however. Alternative explanations for abnormal MIBG uptake in an IH include enhanced blood flow through the lesion or infiltration by sympathetic neural tissue.11

Propranolol has been shown to be superior to other treatment modalities in hastening involution of symptomatic IHs.14 The proposed mechanisms of action are vasoconstriction due to decreased nitric oxide release, downregulation of vascular growth factors and induction of apoptosis through activation of the caspase cascade.4 14 Propranolol has a well-documented safety profile and is typically well tolerated by infants and children. Infants on this medication should be monitored for hypoglycaemia at the time of initiation and followed for the potential side effects of bradycardia, bronchospasm, hypotension and gastrointestinal reflux with continued usage.

At the time of her diagnosis of a visceral IH, this patient had laboratory evidence of hypothyroidism, which had not been present on her prior routine thyroid hormone screens. While hypothyroidism in this patient may have been due in part to a sick euthyroid syndrome of prematurity, it more likely reflects consumptive hypothyroidism related to the IH. IHs overexpress type 3 deiodinase (D3), especially during their proliferative phase in the first months of life. D3 degrades both thyroxine and triiodothyronine into inactive metabolites, leading to hypothyroidism.5 As an IH involutes, the expression of D3 also decreases, allowing for gradual weaning of thyroid hormone supplementation. Our patient continues to undergo frequent checks of her thyroid hormone levels, and it is expected that she will wean off this medication in the near future as her IH continues to involute.

Learning points.

Visceral infantile haemangioma (IH) is a rare cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding and feeding intolerance in infants.

While various imaging modalities may be helpful for diagnosis of visceral IHs, biopsy and histologic analysis may be required in some cases.

Large visceral IHs may take up metaiodobenzylguanidine, leading to a false-positive diagnostic study for neuroblastoma or other neuroendocrine tumours.

Infants with large IHs should undergo thyroid hormone screening, as these lesions can cause consumptive hypothyroidism, especially during their proliferative phase.

Footnotes

Contributors: JK created the initial draft of the manuscript. KR, TC and SC all provided edits to the manuscript. All authors were involved in the initial conception of this manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet 2017;390:85–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00645-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen TS, Eichenfield LF, Friedlander SF. Infantile hemangiomas: an update on pathogenesis and therapy. Pediatrics 2013;131:99–108. 10.1542/peds.2012-1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glick ZR, Frieden IJ, Garzon MC, et al. Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis: an evidence-based review of case reports in the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:898–903. 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nip SY, Hon KL, Leung WK, et al. Neonatal abdominal hemangiomatosis: propranolol beyond infantile hemangioma. Case Rep Pediatr 2016;2016:1–4. 10.1155/2016/9803975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luongo C, Trivisano L, Alfano F, et al. Type 3 deiodinase and consumptive hypothyroidism: a common mechanism for a rare disease. Front Endocrinol 2013;4:115 10.3389/fendo.2013.00115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Drolet BA, Pope E, Juern AM, et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding in infantile hemangioma: a complication of segmental, rather than multifocal, infantile hemangiomas. J Pediatr 2012;160:1021–6. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang LC, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, et al. Growth characteristics of infantile hemangiomas: implications for management. Pediatrics 2008;122:360–7. 10.1542/peds.2007-2767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maruani A, Piram M, Sirinelli D, et al. Visceral and mucosal involvement in neonatal haemangiomatosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012;26:1285–90. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04285.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bombardieri E, Giammarile F, Aktolun C, et al. 131I/123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (mIBG) scintigraphy: procedure guidelines for tumour imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2010;37:2436–46. 10.1007/s00259-010-1545-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Horne T, Glaser B, Krausz Y, et al. Unusual causes of I-131 metaiodobenzylguanidine uptake in non-neural crest tissue. Clin Nucl Med 1991;16:239–42. 10.1097/00003072-199104000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frappaz D, Giammarile F, Thiesse P, et al. False positive MIBG scan. Med Pediatr Oncol 1997;29:589–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rottenburger C, Juettner E, Harttrampf AC, et al. False-positive radio-iodinated metaiodobenzylguanidine (123I-MIBG) accumulation in a mast cell-infiltrated infantile haemangioma. Br J Radiol 2010;83:e168–e171. 10.1259/bjr/40750533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Licup NL, Zaza AA, Copeland RJ, et al. Peri-adrenal hemangioma mimicking a pheochromocytoma on metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scan. Tenn Med 2011;104:39–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lou Y, Peng WJ, Cao Y, et al. The effectiveness of propranolol in treating infantile haemangiomas: a meta-analysis including 35 studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;78:44–57. 10.1111/bcp.12235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]