Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disease with demyelination of the central nervous system. High-dosage corticosteroids are the first-line therapy in the acute relapsing of MS. We report a case of severe high-dose methylprednisolone-induced acute hepatitis in a patient with a new diagnosis of MS. A 16-year-old girl was admitted for urticaria, angioedema, nausea and vomiting a month later she had been diagnosed with MS and treated with high-dosage methylprednisolone. Laboratory investigations showed hepatic insufficiency with grossly elevated liver enzymes. A liver biopsy showed focal centrilobular hepatocyte necrosis with interface hepatitis. Methylprednisolone-induced hepatotoxicity can confuse the clinical picture of patients with MS and complicate the differential diagnosis. We believe that each specialist should know it and monitor patients with MS taking high doses of methylprednisolone. As there is no screening model that predicts idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity, we promote screening for potential liver injury following pulse steroid therapy.

Keywords: paediatrics (drugs And Medicines), liver disease, multiple sclerosis, unwanted effects / adverse reactions, safety

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory disease of the central nervous system characterised by a relapsing-remitting course in 80%–90% of cases.1 MS is characterised by T-cell and macrophage infiltrates leading to demyelination of the central nervous system. During a relapse of MS, it is essential to assess the clinical symptoms and begin appropriate therapy in order to prevent neurological deficits.2 High-dosage corticosteroids (HDCS), such as methylprednisolone, are considered the first-line medical treatment in the acute relapsing period of MS.3 4 Several trials allowed the use of HDCS in combination with disease-modifying drugs (DMDs) to treat acute relapses without unfavourable adverse events.5 6 Among corticosteroids, high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone is the conventional therapy used for MS exacerbations.7 High doses of intravenous methylprednisolone are recommended once a day (20–30 mg/kg, maximum of 1.0 g/day). Furthermore, pulsed methylprednisolone treatment has shown to have a short-term benefit on the speed of functional recovery.3

Many side effects of HDCS are reported in the young population, including mental changes, hypertension, arrhythmias, facial erythema, hyperglycaemia, hepatotoxicity, gastric ulcerations and fluid retention.8 9 However, perhaps not everyone knows the toxic damages to the liver due to methylprednisolone. Hepatotoxicity from HDCS had been described.7 10–24 This condition was related to immunomodulator drugs, autoimmune or viral agents, until recently when the relation between methylprednisolone therapy and hepatotoxicity had been proven.21 25 We report a case of severe high-dose methylprednisolone-induced acute hepatitis in a 16-year-old girl with a new diagnosis of MS, describing clinical, laboratory and histological data after 2 years of follow-up.

Case presentation

A 16-year-old girl was admitted to the emergency room in June 2016 for acute liver injury with urticaria on the chest and limbs, angioedema, nausea and vomiting.

One month before, she was diagnosed with MS, in accord with the most recent criteria,26 and treated with a 5-day course of intravenous methylprednisolone (total dose 1.0 g/day); to dismissal from the hospital on the fifth day, liver enzymes were within normal limits.

The patient refrained from taking any prescribed or recreational hepatotoxic drugs. She also denied any alcohol use and sexual promiscuity. She did not take any other drugs in the last month.

Investigations

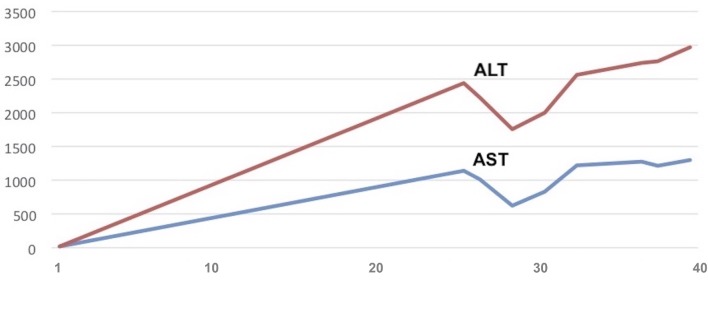

Laboratory investigations showed grossly elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 2438 U/L (normal <66 U/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 1142 U/L (normal <46 U/L), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) of 2698 U/L (normal <618 U/L), gamma-glutamyltransferase of 68 U/L (normal <43 U/L), total bilirubin of 2.10 mg/dL, mainly indirect (normal <1.30 U/L), ACE of 67 μg/L (normal <21 μg/L) and biliary acids of 10.3 mmol/L (normal <1.23 mmol/L). Figure 1 shows the AST and ALT levels during the recovery, which remained high.

Figure 1.

Trend of liver function tests during recovery. The figure shows AST and ALT augmentation during hospitalisation. The horizontal axis specifies the day from admission. On the vertical axis AST (normal <46 U/L) and ALT (normal <66 U/L) values are reported. AST/ALT values remained high for about 2 weeks. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

A systematic search of the classical causes of acute hepatitis was performed. Serological tests for hepatitis (serum anti-Hepatitis A virus (HAV) IgM antibodies, Hepatitis B antigen (HBsAg), Hepatitis B virus (HBV)-DNA, anti-Hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies and HCV-RNA) and hepatotropic viruses (Human herpesvirus (HHV6), cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein Barr virus (EBV), adenovirus, parvovirus B19, Coxsackie A–B and echovirus) were negative. Coprocultures for virus (rotavirus) and bacteria (Shigella, Salmonella typhi, Campylobacter, Yersinia and Aeromonas) were negative. Widal-Wright was negative. IgM Herpes simplex virus (HSV) 1–2 were increased slightly. Similarly, antinuclear, antimitochondrial, antismooth muscle and anti-liver-kidney microsomal 1 (LKM1) antibodies were negative.

Renal function, serum electrolytes, glycaemia, protein electrophoresis, ammonaemia, thyroid function, lipase, alpha-1-antitrypsin, creatine kinase and urine analysis were normal. There are no data on thrombosis, and coagulation screening was within normal limits. Repeat abdominal ultrasound scans revealed an intact liver, bile ducts and normal-sized spleen. There were no signs of storage diseases (iron, copper); ceruloplasmin, ferritin and serum iron were within normal limits. The ophthalmologist excluded the presence of Kayser-Fleischer ring. Considering her young age, the levels of recreational drugs in the blood/urine and of alcohol in the blood were not determined.

A liver biopsy was performed and showed focal centrilobular hepatocyte necrosis with interface hepatitis, supporting the diagnosis of drug-induced hepatitis.

Treatment

The patient was prescribed antihistaminergic drugs for 6 days, infusion of physiological solution, a ‘hepatic diet’ and acetylcysteine 600 mg for liver detoxification.

Outcome and follow-up

During hospitalisation the patient had no fever, vomiting, diarrhoea, itch and abdominal pain. Liver enzymes returned to normal limits within 2 months from the onset of symptoms.

Our patient was not administered any disease-modifying treatment before the hepatitis. The first-line therapy (glatiramer acetate) was started 3 months after hepatitis.

For 2 years our patient presented radiological stability (as shown by MRI of the brain) in the absence of clinical relapses and disease activity, with a low degree of disability (Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)=1).

Since the diagnosis of methylprednisolone-induced hepatotoxicity, she had not experienced any further relapses or hepatotoxic events in the following 2 years. At follow-up visits liver enzymes had returned to normal limits and the patient had no signs of hepatitis.

Discussion

To date a limited number of cases of methylprednisolone-induced hepatotoxicity had been described.7 10–24 We report an idiosyncratic toxic hepatitis from high-dose methylprednisolone in a 16-year-old girl.

Corticosteroid-induced hepatitis requires exclusion of alternative diagnoses, and timely recognition of this drug-related reaction is important.12 14

Immunomodulatory drugs or DMDs significantly reduce the frequency and severity of clinical relapses and disease activity.27 These drugs reduce relapses in adults by as much as 30%.28 29 However, DMDs are known to induce hepatotoxicity rarely, and younger patients usually have increased levels of liver enzymes.30

There are a few cases that described liver injury after methylprednisolone therapy in patients with MS, most of them not receiving DMD for MS.

Our patient was not administered any DMD before the hepatitis, and methylprednisolone was the only therapy administered before hepatitis. In fact, 3 months after hepatitis, our patient was prescribed glatiramer acetate, an immunomodulator drug which inhibits effector T-cells and regulates antigen-presenting cells and suppressor T-lymphocytes.28 This is a usually well-tolerated drug advisable for long-term use.31

The patient refrained from taking any prescribed or hepatotoxic drugs and also denied any alcohol use, and the levels of recreational drugs in the blood/urine and of alcohol and further substances in the blood were not determined. This is a relevant limitation because recreational drugs, alcohol and further substances (eg, herbal drugs) may play a relevant role in triggering or intensifying hepatotoxicity.32–37 Exposure to other possible aetiological agent was excluded. The combination of clinical, laboratory and histological data suggested a diagnosis of methylprednisolone-induced toxic hepatitis. The side effect in this patient was specific for high-dose methylprednisolone,12 and it was classified as ‘probable adverse drug reaction’.21

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a complex process and represents a major cause of liver damage. DILI has an estimated annual incidence of between 10 and 15 per 10 000–100 000 persons exposed to prescription medications. Several risk factors have been associated with the development of DILI. Adults are at higher risk than children and females may be more susceptible.38

The mechanism of hepatotoxicity involves the drug itself, its metabolites and the host immune system.39 Several types of drugs may lead to hepatocyte necrosis or apoptosis and subsequent cell death. Some drugs predominantly damage the bile ducts, biliary export proteins or bile canaliculi (cholestasis), vascular endothelial cells (sinusoidal obstruction syndrome), or the stellate cells. There may also be mixed patterns of injury.40 Hepatocellular toxicity may be classified in several ways, including pathogenic mechanism (intrinsic vs idiosyncratic drug-induced hepatotoxicity), clinical features (patterns of liver injury) and histological findings.

Presentations of DILI41 may vary from an asymptomatic form (mild liver test abnormalities) to cholestasis with pruritus, an acute illness with jaundice and acute liver failure. Chronic liver injury caused by drugs can resemble other causes. Differential diagnosis includes several diseases such as autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, sclerosing cholangitis or alcoholic liver disease.

We have presented a rare case of corticosteroid-induced liver injury in a young patient affected by MS. This condition may occur as acute hepatitis that develops for several weeks up to 6 months12 15 after short-term drug exposure from steroid therapy, and prognosis varies from complete recovery to death.25

Toxic hepatitis due to high-dose methylprednisolone therapy is an adverse event rarely reported in the literature.13 In addition, while pulsed methylprednisolone treatment has shown to have a short-term benefit on functional recovery in acute exacerbations of MS, it was also reported that hepatotoxicity occurred after repeated cycles of intravenous methylprednisolone.25

Nociti et al 23 performed a prospective observational study on patients with MS after methylprednisolone therapy and observed a prevalence of 8.6% of liver injury. They described six cases of patients with severe liver injury after pulsed methylprednisolone therapy; five of them were female and three of them with a probable autoimmune hepatitis.

Further investigations are needed in order to evaluate the link between methylprednisolone administration and the occurrence of autoimmune hepatitis.

Previous papers have highlighted the presence of other autoimmune diseases in several cases of patients with MS presenting DILI, but these data are not present in our case.

Previously described cases regarded mainly women with a mean age of 40 years and, to our knowledge, five cases of adolescent patients have been described.

The risk factors for corticosteroid-induced liver injury are age above 50 years, female gender and smoking.25 However, in accord with the literature, our patient showed young age and female gender as risk factors.

Although corticosteroid therapy is associated with liver injury, idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity is unpredictable. Therefore, assessment of liver function (especially transaminases) during and following HDCS treatment allows discontinuation of the drug and prevents liver injury.

Liver injury caused by corticosteroids varied from asymptomatic hypertransaminasaemia to fulminant hepatic failure.10–24 Acute presentations include mild liver test abnormalities, cholestasis with pruritus, and sometimes acute liver failure mimicking aggressive conditions such as viral hepatitis. In the remaining cases, chronic liver injury may suggest an autoimmune hepatitis or primary biliary cirrhosis in the young patient. Atypical presentations can confuse the clinical picture and complicate the differential diagnosis. However, in patients with other autoimmune diseases, such as MS, it is difficult to make the correct diagnosis because immune-mediated liver toxicity shares similar immunological pathogenesis.

Screening protocols should be used in clinical practice. We suggest a close follow-up of liver function tests (transaminase) following pulsed methylprednisolone treatment.

According to our experience and the literature, we recommend testing transaminases in all patients with MS before pulsed methylprednisolone treatment and 2 weeks after. Moreover we suggest a wide monitoring of liver function (gamma-glutamyltransferase, direct and total bilirubin) at least once.

In patients at risk, closer monitoring of liver function has been proposed: once a week during pulse therapy and once a month for the subsequent year.21 42

Several treatment options have been proposed in the literature for patients with relapses of MS.43 44 However, even if our patient did not experience further exacerbations, adrenocorticotropic hormone as a first measure and then dexamethasone and plasma exchange seem to be reliable among the most common treatments, according to published data.45–51

Conclusions

Patients with hepatitis should be well investigated. A careful medical history is essential, including drug exposure, concomitant disease, alcohol consumption and use of complementary medicine (eg, herbal medications).

Although the mechanisms of corticosteroid-induced liver injury are unclear, our case underlines the possible effects of high-dose glucocorticoids in the induction of liver enzymes, especially in young patients. In order to prevent potential liver injury, an early diagnosis is necessary.

Clinicians increasingly use pulse steroid therapies to treat various inflammatory or autoimmune diseases, but general awareness of the potential hepatotoxicity of HDCS is very low. Although hepatitis rarely occurs after steroids, and the real incidence of this toxicity is probably underestimated, it is important to be aware of this toxicity in order to avoid repeated administration of methylprednisolone, especially in patients affected by liver diseases.

This diagnosis is based on a strong clinical suspicion, accurate anamnesis and overall exclusion of other causes.15 21 Age above 50 years, female gender and smoking are considered risk factors.25

We believe that each specialist should know it and monitor patients with MS taking high doses of methylprednisolone. In order to avoid potential drug-related risks, an early recognition of corticosteroid-related liver disease is essential. Even if there is no screening model that predicts idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity, we promote screening for potential liver injury following pulse steroid therapy.

Learning points.

Corticosteroid-induced hepatitis is a rare and life-threatening adverse event that can develop several weeks after short-term drug exposure from methylprednisolone administration.

Clinicians increasingly use pulse steroid therapies to treat various inflammatory or autoimmune diseases, but general awareness of the potential hepatotoxicity of high-dose corticosteroids is very low.

Acute presentations of corticosteroid-induced liver injury include mild liver test abnormalities, cholestasis with pruritus, and sometimes acute liver failure mimicking aggressive conditions such as viral hepatitis; in the remaining cases, chronic liver injury may suggest an autoimmune hepatitis or primary biliary cirrhosis in the young patient.

Patients with multiple sclerosis taking high doses of methylprednisolone should be screened for potential liver injury, with wide monitoring of liver function (gamma-glutamyltransferase, direct and total bilirubin) and monitored through close follow-up of liver function tests (transaminase) until 2 weeks after therapy.

In patients at risk, closer monitoring of liver function tests was proposed during pulse therapy and periodically for the subsequent 12 months.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Giovanna De Luca and Dr Giuseppe Maggiore for supporting us during evaluation of our patient, diagnosis and management.

Footnotes

Contributors: ER and AG provided clinical care to the patient, and were responsible for conception and design, acquisition of the data, and analysis and interpretation of the data. VDS and AAM revised the article critically for intellectual content. All authors contributed to and have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2008;372:1502–17. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Narula S. New Perspectives in Pediatric Neurology-Multiple Sclerosis. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2016;46:62–9. 10.1016/j.cppeds.2015.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smets I, Van Deun L, Bohyn C, et al. . Corticosteroids in the management of acute multiple sclerosis exacerbations. Acta Neurol Belg 2017;117:623–33. 10.1007/s13760-017-0772-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goodin DS, Frohman EM, Garmany GP, et al. . Disease modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: report of the therapeutics and technology assessment subcommittee of the american academy of neurology and the ms council for clinical practice guidelines. Neurology 2002;58:169–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thompson AJ, Kennard C, Swash M, et al. . Relative efficacy of intravenous methylprednisolone and ACTH in the treatment of acute relapse in MS. Neurology 1989;39:969–71. 10.1212/WNL.39.7.969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fox RJ, Miller DH, Phillips JT, et al. . Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 or glatiramer in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1087–97. 10.1056/NEJMoa1206328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Das D, Graham I, Rose J. Recurrent acute hepatitis in patient receiving pulsed methylprednisolone for multiple sclerosis. Indian J Gastroenterol 2006;25:314–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patel Y, Bhise V, Krupp L, et al. . Pediatric multiple sclerosis. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2009;12:238–45. 10.4103/0972-2327.58281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goodin DS, Reder AT, Bermel RA, et al. . Relapses in multiple sclerosis: relationship to disability. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2016;6:10–20. 10.1016/j.msard.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Takahashi A, Kanno Y, Takahashi Y, et al. . Development of autoimmune hepatitis type 1 after pulsed methylprednisolone therapy for multiple sclerosis: a case report. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:5474–7. 10.3748/wjg.14.5474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rivero Fernández M, Riesco JM, Moreira VF, et al. . [Recurrent acute liver toxicity from intravenous methylprednisolone]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2008;100:720–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gutkowski K, Chwist A, Hartleb M. Liver injury induced by high-dose methylprednisolone therapy: a case report and brief review of the literature. Hepat Mon 2011;11:656–61. 10.5812/kowsar.1735143X.713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Furutama D, Kimura F, Shinoda K, et al. . Recurrent high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone succinate pulse therapy-induced hepatopathy in a patient with multiple sclerosis. Med Princ Pract 2011;20:291–3. 10.1159/000323835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carrier P, Godet B, Crepin S, et al. . Acute liver toxicity due to methylprednisolone: consider this diagnosis in the context of autoimmunity. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2013;37:100–4. 10.1016/j.clinre.2012.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. D’Agnolo HM, Drenth JP, Neth J. High-dose methylprednisolone-induced hepatitis in a patient with multiple sclerosis: a case report and brief review of literature. Med 2013;71:199–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oliveira AT, Lopes S, Cipriano MA, et al. . Induced liver injury after high-dose methylprednisolone in a patient with multiple sclerosis. BMJ Case Rep 2015;21:bcr2015210722 10.1136/bcr-2015-210722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ferraro D, Mirante VG, Losi L, et al. . Methylprednisolone-induced toxic hepatitis after intravenous pulsed therapy for multiple sclerosis relapses. Neurologist 2015;19:153–4. 10.1097/NRL.0000000000000029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grilli E, Galati V, Petrosillo N, et al. . Incomplete septal cirrhosis after high-dose methylprednisolone therapy and regression of liver injury. Liver Int 2015;35:674–6. 10.1111/liv.12607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Davidov Y, Har-Noy O, Pappo O, et al. . Methylprednisolone-induced liver injury: case report and literature review. J Dig Dis 2016;17:55–62. 10.1111/1751-2980.12306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dumortier J, Cottin J, Lavie C, et al. . Methylprednisolone liver toxicity: a new case and a french regional pharmacovigilance survey. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2017;41:497–501. 10.1016/j.clinre.2017.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hidalgo de la Cruz M, Miranda Acuña JA, Lozano Ros A, et al. . Hepatotoxicity after high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone in multiple sclerosis patients. Clin Case Rep 2017;5:1210–2. 10.1002/ccr3.1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bresteau C, Prevot S, Perlemuter G, et al. . Methylprednisolone-induced acute liver injury in a patient treated for multiple sclerosis relapse. BMJ Case Rep 2018;2018 10.1136/bcr-2017-223670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nociti V, Biolato M, De Fino C, et al. . Liver injury after pulsed methylprednisolone therapy in multiple sclerosis patients. Brain Behav 2018;8:e00968 10.1002/brb3.968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Adamec I, Pavlović I, Pavičić T, et al. . Toxic liver injury after high-dose methylprednisolone in people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2018;25:43–5. 10.1016/j.msard.2018.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Caster O, Conforti A, Viola E, et al. . Methylprednisolone-induced hepatotoxicity: experiences from global adverse drug reaction surveillance. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2014;70:501–3. 10.1007/s00228-013-1632-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. . Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69:292–302. 10.1002/ana.22366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jančić J, Nikolić B, Ivančević N, et al. . Multiple Sclerosis Therapies in Pediatric Patients: Challenges and Opportunities : Zagon IS, McLaughlin PJ, Multiple Sclerosis: perspectives in treatment and pathogenesis.. Brisbane (AU): Codon Publications, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chitnis T. Disease-modifying therapy of pediatric multiple sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics 2013;10:89–96. 10.1007/s13311-012-0158-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dujmovic I, Jancic J, Dobricic V, et al. . Are Leber’s mitochondial DNA mutations associated with aquaporin-4 autoimmunity? Mult Scler 2016;22:393–4. 10.1177/1352458515590649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ghezzi A, Amato MP, Makhani N, et al. . Pediatric multiple sclerosis: conventional first-line treatment and general management. Neurology 2016;87:S97–102. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ghezzi A. Therapeutic strategies in childhood multiple sclerosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2010;3:217–28. 10.1177/1756285610371251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Solimini R, Busardò FP, Rotolo MC, et al. . Hepatotoxicity associated to synthetic cannabinoids use. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2017;21(1 Suppl):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tarantino G, Citro V, Finelli C. Recreational drugs: a new health hazard for patients with concomitant chronic liver diseases. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2014;23:79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Antolino-Lobo I, Meulenbelt J, van den Berg M, et al. . A mechanistic insight into 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy”)-mediated hepatotoxicity. Vet Q 2011;31:193–205. 10.1080/01652176.2011.642534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Borini P, Guimarães RC, Borini SB. Possible hepatotoxicity of chronic marijuana usage. Sao Paulo Med J 2004;122:110–6. 10.1590/S1516-31802004000300007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhu J, Seo JE, Wang S, et al. . The Development of a Database for Herbal and Dietary Supplement Induced Liver Toxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19:2955 10.3390/ijms19102955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brewer CT, Chen T. Hepatotoxicity of herbal supplements mediated by modulation of cytochrome P450. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18:2353 10.3390/ijms18112353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sgro C, Clinard F, Ouazir K, et al. . Incidence of drug-induced hepatic injuries: a French population-based study. Hepatology 2002;36:451–5. 10.1053/jhep.2002.34857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen M, Suzuki A, Borlak J, et al. . Drug-induced liver injury: Interactions between drug properties and host factors. J Hepatol 2015;63:503–14. 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Holt MP, Ju C. Mechanisms of drug-induced liver injury. Aaps J 2006;8:E48–54. 10.1208/aapsj080106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chang CY, Schiano TD. Review article: drug hepatotoxicity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;25:1135–51. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03307.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Eguchi H, Tani J, Hirao S, et al. . Liver dysfunction associated with intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy in patients with graves’ orbitopathy. Int J Endocrinol 2015;2015:1–5. 10.1155/2015/835979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stoppe M, Busch M, Krizek L, et al. . Outcome of MS relapses in the era of disease-modifying therapy. BMC Neurol 2017;17:151 10.1186/s12883-017-0927-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Berkovich RR. Acute multiple sclerosis relapse. Continuum 2016;22:799–814. 10.1212/CON.0000000000000330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Berkovich R, Bakshi R, Amezcua L, et al. . Adrenocorticotropic hormone versus methylprednisolone added to interferon β in patients with multiple sclerosis experiencing breakthrough disease: a randomized, rater-blinded trial. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2017;10:3–17. 10.1177/1756285616670060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kutz CF, Dix AL. Repository corticotropin injection in multiple sclerosis: an update. Neurodegener Dis Manag 2018;8:217–25. 10.2217/nmt-2018-0008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gao H, Gao Y, Li X, et al. . Spatiotemporal patterns of dexamethasone-induced Ras protein 1 expression in the central nervous system of rats with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Mol Neurosci 2010;41:198–209. 10.1007/s12031-009-9322-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Goodin DS. Glucocorticoid treatment of multiple sclerosis. Handb Clin Neurol 2014;122:455–64. 10.1016/B978-0-444-52001-2.00020-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Faissner S, Nikolayczik J, Chan A, et al. . Plasmapheresis and immunoadsorption in patients with steroid refractory multiple sclerosis relapses. J Neurol 2016;263:1092–8. 10.1007/s00415-016-8105-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ehler J, Blechinger S, Rommer PS, et al. . Treatment of the first acute relapse following therapeutic plasma exchange in formerly glucocorticosteroid-unresponsive multiple sclerosis patients-a multicenter study to evaluate glucocorticosteroid responsiveness. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18:1749 10.3390/ijms18081749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Correia I, Ribeiro JJ, Isidoro L, et al. . Plasma exchange in severe acute relapses of multiple sclerosis - Results from a portuguese cohort. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2018;19:148–52. 10.1016/j.msard.2017.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]