Abstract

L-ascorbate (L-ASC) is a widely-known dietary nutrient which holds promising potential in cancer therapy when given parenterally at high doses. The anticancer effects of L-ASC involve its autoxidation and generation of H2O2, which is selectively toxic to malignant cells. Here we present that thioredoxin antioxidant system plays a key role in the scavenging of extracellularly-generated H2O2 in malignant B-cells. We show that inhibition of peroxiredoxin 1, the enzyme that removes H2O2 in a thioredoxin system-dependent manner, increases the sensitivity of malignant B-cells to L-ASC. Moreover, we demonstrate that auranofin (AUR), the inhibitor of the thioredoxin system that is used as an antirheumatic drug, diminishes the H2O2-scavenging capacity of malignant B-cells and potentiates pharmacological ascorbate anticancer activity in vitro and in vivo. The addition of AUR to L-ASC-treated cells triggers the accumulation of H2O2 in the cells, which results in iron-dependent cytotoxicity. Importantly, the synergistic effects are observed at as low as 200 µM L-ASC concentrations. In conclusion, we observed strong, synergistic, cancer-selective interaction between L-ASC and auranofin. Since both of these agents are available in clinical practice, our findings support further investigations of the efficacy of pharmacological ascorbate in combination with auranofin in preclinical and clinical settings.

Abbreviations: AUR, auranofin; BSO, buthionine sulfoximine; BL, Burkitt lymphoma; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CAT, catalase; D-ASC, D-ascorbate; DFO, deferoxamine; GOx, glucose oxidase; GSH, glutathione; L-ASC, L-ascorbate; L-DHA, L-dehydroascorbate; PRDX, peroxiredoxin; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TXN, thioredoxin; TXNRD, thioredoxin reductase

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Lack of peroxiredoxin 1 potentiates antileukemic activity of L-ascorbate in vitro and in vivo.

-

•

Auranofin and L-ascorbate synergistically kill malignant B cells.

-

•

Auranofin leads to intracellular accumulation of H2O2 generated by L-ascorbate.

-

•

Auranofin and L-ascorbate trigger iron-dependent oxidative damage and cytotoxicity.

1. Introduction

L-ascorbate (L-ASC), widely-known as vitamin C, is a non-toxic and clinically applicable compound, which holds potential in cancer therapy. In physiological concentrations (~50 μM in human serum [1]), L-ASC acts as an antioxidant. However, the antitumor effects of L-ASC rely on its prooxidant properties [2], [3] and are observed after parenteral administration of high doses of L-ASC (pharmacological ascorbate), which results in up to 25 mM concentration in plasma [4]. In contrast, oral administration results in maximally 200 μM L-ASC and provides no apparent benefit to cancer patients [4]. Preclinical and clinical trials have repeatedly demonstrated that pharmacological ascorbate given parenterally in high doses can be safely administered to patients [5], [6]. Importantly, recent reports provide encouraging data supporting the anticancer efficacy of pharmacological ascorbate, showing that high doses of intravenous L-ASC improve the clinical outcomes of chemo- and radiotherapy in cancer patients [7], [8]. Furthermore, it has been recently demonstrated that L-ASC induces differentiation and apoptosis of acute myeloid leukemia cells harboring isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations via epigenetic remodeling [9].

According to previous publications, the mechanism of L-ASC anticancer activity is associated with its ability to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS). Yun et al. [10] reported that ROS generated intracellularly by L-dehydroascorbate (L-DHA), an oxidized form of L-ASC, are responsible for selective cytotoxicity of L-ASC in colon cancer cells overexpressing L-DHA transporter – glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1). In other studies, it was demonstrated that L-ASC generates H2O2 extracellularly in a cell-free medium in the presence of transient metal ions [11]. As H2O2 is relatively stable and readily diffuses through the plasma membrane, it effectively enters the cells and in >100 µM concentrations exerts cytotoxic effects. Extracellularly generated H2O2 was recently demonstrated to be a major trigger of L-ASC cytotoxicity in lung cancer and glioma cells [7].

The cytotoxic effects of H2O2 are concentration-dependent and can be significantly diminished by the activity of the antioxidant systems responsible for H2O2 removal. The major H2O2 scavenging enzymes include glutathione (GSH) peroxidases, thioredoxin (TXN)-dependent peroxiredoxins (PRDXs), and catalase [12], [13]. It is well documented that cancer cells have elevated ROS levels, which are accompanied by dysregulated expression of antioxidant enzymes [14]. It is postulated that the selective toxicity of L-ASC to malignant cells is due to the decreased overall capacity of the cells to metabolize H2O2 [15].

Malignant B-cells are sensitive to L-ASC in vitro, with LD50 of ~0.5 mM [11], however, the anti-B cell lymphoma activity of pharmacological ascorbate in monotherapy in vivo is limited [16]. The antitumor activity of pharmacological ascorbate towards malignant B-cells may be hampered by the upregulation of TXN-dependent antioxidant enzymes in these B-cells [17], [18]. This may be particularly relevant in vivo, where stromal cells provide additional redox-protective support to malignant cells [19]. We hypothesized that the selective killing of malignant B-cells by L-ASC could be potentiated by targeting the TXN antioxidant system. Here, we present evidence that downregulation of PRDX1 sensitizes malignant B-cells to L-ASC in vitro and in vivo. We demonstrate that pharmacological ascorbate combined with auranofin (AUR), an inhibitor of the TXN system, synergistically kills primary chronic lymphocytic leukemia B-cells. Importantly, our studies also indicate the in vivo efficacy of this combination in a murine B-cell lymphoma model.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Inhibition of TXN-dependent H2O2 removal potentiates L-ASC activity against malignant B-cells in vitro and in vivo

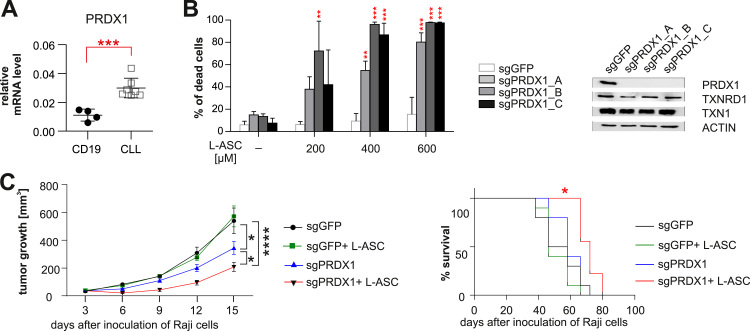

To investigate whether inhibition of TXN and GSH antioxidant systems influences anticancer effects of L-ASC, we employed SK053, an inhibitor of TXN, thioredoxin reductase (TXNRD) and dimeric PRDXs [18], [20], and a buthionine sulfoximine (BSO), an inhibitor of GSH biosynthesis [21]. Inhibition of the TXN system greatly enhanced L-ASC cytotoxicity towards the malignant B-cell lines Raji and Mec-1, while inhibition of the glutathione system had no effect (Supplementary Fig. 1). The role of the TXN-TXNRD system in H2O2 removal is mainly related to its ability to reduce PRDXs. There are six PRDXs in mammals, of which PRDX1–5 are TXN-dependent [22]. We have previously shown that PRDX1 and PRDX2 are upregulated in Burkitt lymphoma (BL) cells and support the proliferation of BL cell lines [18]. Here, we demonstrate that in primary tumor cells derived from patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the most common type of leukemia in adults, from all the TXN system antioxidant enzymes, only PRDX1 is significantly overexpressed at both mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Fig. 2A-B). Accordingly, the BL cell line Namalwa with PRDX1 knock-down was more sensitive to L-ASC than control cells or cells with reduced expression of PRDX2, suggesting the major role of PRDX1 in H2O2 detoxification in malignant B-cells (Supplementary Fig. 3). Raji cells, another representative of BL, with PRDX1 genome-targeted knockout (Raji-sgPRDX1), were much more sensitive to L-ASC, despite unperturbed protein levels of TXN1 and TXNRD1 in the PRDX1-deficient clones (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Lack of PRDX1 sensitizes malignant B-cells to pharmacological ascorbate in vitro and in vivo. A. The mRNA levels of PRDX1 in normal (CD19+ cells from peripheral blood of healthy donors, n = 4) and malignant (primary CLL, n = 7) B-cells were assessed by qPCR, using RPL29 gene as a reference. The results are shown as means ± SD. Statistical significance was assessed using unpaired t-test with Welch's correction; ***p < 0.001. B. PRDX1 knockout (3 different clones: Raji-sgPRDX1 A, B, and C) or control (Raji-sgGFP) cells were incubated with L-ASC at indicated concentrations for 48 h. To assess viability, the cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) and analyzed by flow cytometry (left panel). The results are presented as % of dead cells (PI-positive cells) and show means + SD, n ≥ 4. Statistical significance between control (sgGFP) and PRDX1 knockout clones for each L-ASC concentration was assessed using 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Western blot analysis of total protein lysates prepared from PRDX1 knockout and control Raji cells (right panel). C. BALB/c SCID mice were inoculated subcutaneously with Raji-sgPRDX1 (a mixture of clones B and C) and Raji-sgGFP cells. L-ASC was administered intraperitoneally at a dose of 4 g/kg, twice daily, for 10 days. The graphs represent results from two pooled experiments, the number of mice in each group was 10. Statistical significance of tumor growth (left panel) between the following groups: Raji-sgGFP and Raji-sgPRDX1, Raji-sgGFP+L-ASC and Raji-sgPRDX1+L-ASC, as well as Raji-sgPRDX1 and Raji-sgPRDX1+L-ASC was assessed using 2-way ANOVA; *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001. Statistical significance of mice survival (right panel) was determined using log-rank survival test; *p < 0.05.

To determine if lack of PRDX1 affects antitumor efficacy of pharmacological ascorbate in vivo, we inoculated BALB/c SCID mice with control (Raji-sgGFP) or PRDX1 knockout (Raji-sgPRDX1) cells. In line with the published in vitro results [18], in untreated mice, the growth of Raji-sgPRDX1 tumors was slower than Raji-sgGFP controls. While L-ASC failed to inhibit the growth of control Raji-sgGFP tumors, it showed significant antitumor effects against Raji-sgPRDX1 tumors (Fig. 1C, left panel), despite a relatively rapid decline of L-ASC concentration in mouse serum (Supplementary Table 1). Mice inoculated with Raji-sgPRDX1 and treated with L-ASC survived longer than the control, treated mice (Fig. 1C, right panel). These results indicate that blocking the activity of PRDX1 is an attractive strategy to enhance pharmacological ascorbate antitumor effects in vivo.

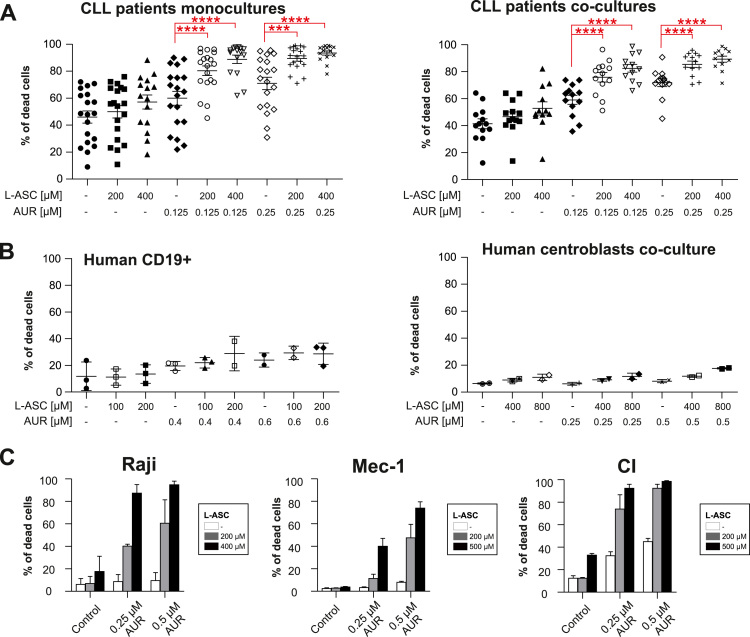

2.2. TXNRD inhibition enhances L-ASC activity against malignant B-cells

Due to the lack of clinically-applicable PRDX1 inhibitors, we investigated whether inhibition of TXNRD1, the superordinate enzyme of the TXN system, would also affect the sensitivity to L-ASC. We observed that Raji cells with reduced TXNRD1 expression were more sensitive to L-ASC (Supplementary Fig. 4). Therefore, to enable clinical translation of these findings, we employed AUR, the inhibitor of the TXNRD that is an approved anti-rheumatic drug, with documented efficacy in CLL [23] and in classical Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma preclinical models [24]. We observed potent, synergistic cytotoxic effects of pharmacological ascorbate and AUR in primary human CLL cells in monocultures as well as in co-cultures with stromal cells (Fig. 2A). The combined L-ASC+AUR treatment was more effective in primary human CLL cells with unmutated IGVH genes (U-CLL), which is linked to worse prognosis in this malignancy, and equally effective in cells isolated from patients from various cytogenetic risk groups (Supplementary Fig. 5). Importantly, the combined treatment resulted in mild toxicity to normal peripheral blood B-cells and no toxicity to centroblasts cultured ex vivo (Fig. 2B). Consistently, AUR markedly sensitized BL and CLL cell lines to pharmacological ascorbate treatment (Fig. 2C). Chou-Talalay analysis revealed the interaction to be synergistic or strongly synergistic in all investigated cell lines and primary B-CLL cells (Supplementary Table 2). In Raji cells, the combination treatment dose-dependently induced mitochondrial membrane depolarization (Supplementary Fig. 6A) and triggered apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. 6B).

Fig. 2.

AUR, an inhibitor of TXNRD, selectively enhances pharmacological ascorbate activity against malignant B-cells. A. Primary human CLL cells grown in monoculture (n ≥ 15 patients, left panel) and in a co-culture with M2–10B4 stromal cells (n ≥ 12 patients, right panel) were incubated for 48 h with indicated concentrations of L-ASC, AUR, or their combination. The percentage of apoptotic cells (% of dead cells) was assessed by annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) staining. Means ± SEM are presented. Statistical significance was evaluated using 1-way ANOVA test with Tukey's correction in AUR only groups vs combinations; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. B. Normal human peripheral blood B-cells (human CD19+) grown in monoculture (n ≥ 2 donors, left panel) and B-cells isolated from human tonsils and co-cultured with HT1080-CD40L cells (centroblasts culture, n = 2 donors, right panel) were incubated with indicated concentrations of L-ASC, AUR or their combination. After 48 h, the percentage of dead cells was assessed by annexin V/PI staining. Means ± SD are presented. C. Human BL cell line Raji and CLL cell lines (Mec-1 and CI) were incubated with L-ASC, AUR, or both at indicated concentrations. After 48 h cells were stained with PI and the percentage of PI-positive cells was assessed by flow cytometry. The results are shown as means of three independent experiments + SD.

Previous studies reported that intraperitoneally (i.p.) administered AUR inhibits TXNR activity in vivo, measured in tumor lysates [25]. Accordingly, the addition of AUR to L-ASC-treated BALB/c-SCID mice inoculated with Raji cells decreased tumor growth and improved mice survival (Supplementary Fig. 7). Altogether, these results indicate that AUR potentiates pharmacological ascorbate toxicity against primary CLL cells, BL and CLL cell lines as well as improves pharmacological ascorbate antitumor activity in mice. Remarkably, this combination displays selective cancer cell killing activity while leaving normal cells intact.

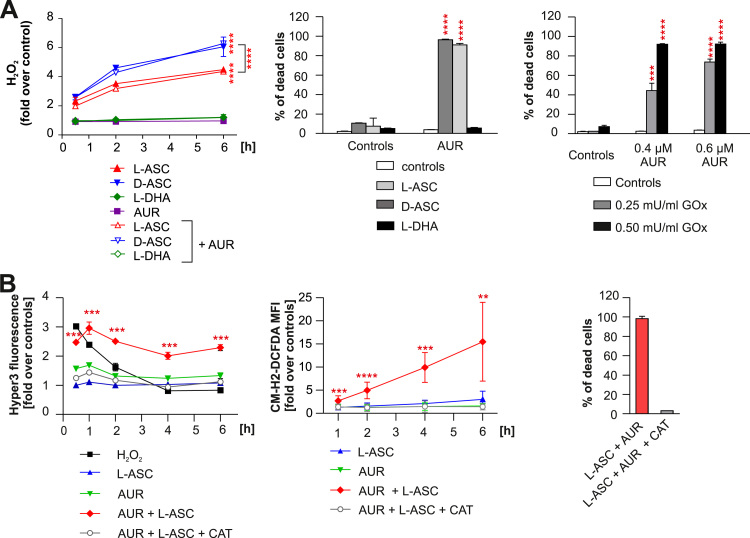

2.3. AUR potentiates the cytotoxicity of extracellularly-generated H2O2

It had been previously demonstrated that L-ASC generates H2O2 in serum-containing culture medium [11]. To investigate if AUR affects H2O2 generation by L-ASC in the culture medium, we employed H2O2-specific fluorescent probe PY1 [26]. As shown in Fig. 3A (left panel), L-ASC alone and in combination with AUR generated similar amounts of H2O2. D-ASC, the stereoisomer of L-ASC with more potent antioxidant properties [27], in our settings generated even higher amounts of H2O2, which were unaffected in the presence of AUR. In contrast, no H2O2 in the medium was generated by L-DHA, an oxidized form of L-ASC. The generation of H2O2 was completely abolished by the addition of catalase, the H2O2 scavenger, to the culture medium, confirming the specificity of the PY1 probe (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Fig. 3.

L-ASC and AUR combination triggers the intracellular accumulation of H2O2 and H2O2-dependent cell death. A. Cell-free culture medium supplemented with 200 µM L-ASC, 200 µM D-ascorbate (D-ASC) or 200 µM L-dehydroascorbate (L-DHA) alone or in combination with 0.5 µM AUR was incubated for indicated time-points. PY1 probe was added to the medium at 10 μM final concentration. The fluorescence was measured using the excitation wavelength 514 nm and emission wavelength 550 nm. The amount of generated H2O2 was normalized to control (DMSO). The representative result (out of two independent experiments) is shown as means ± SD (n = 4). Statistical significance was evaluated using 2-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test and is shown for control vs L-ASC, control vs D-ASC and L-ASC vs D-ASC groups only; **** p < 0.0001 (left panel). Raji cells were incubated with 200 µM L-ASC, 200 µM D-ASC or 200 µM L-DHA alone or in combination with 0.4 µM AUR for 48 h. Thereafter the cells were stained with PI and their viability was assessed by flow cytometry. The results are shown as a mean percentage of dead cells + SD from two independent experiments. Statistical significance was evaluated using 1-way ANOVA test with Tukey's correction in L-ASC, D-ASC and L-DHA only groups and the corresponding combinations, ****p < 0.0001 (middle panel). Raji cells were incubated with glucose oxidase (GOx) and AUR at indicated concentrations, alone or in combination. After 48 h, the cells were stained with PI and the percentage of dead cells was evaluated by flow cytometry. Results are shown as means of three independent experiments + SD. Statistical significance was evaluated using 1-way ANOVA test with Tukey's correction in GOx only groups and the corresponding combinations with AUR, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (right panel). B. Raji cells expressing HyPer3 were incubated with 200 µM L-ASC, 0.5 µM AUR, or the combination of both. Where indicated, catalase (CAT,100 µg/ml) was added 30 min prior to addition of L-ASC and AUR. The intensity of green fluorescence was assessed at indicated time points by flow cytometry. The results are presented as fold change over untreated controls, as means from two experiments ± SD, n = 4. Statistical significance in control vs L-ASC+AUR group only for each time point was assessed using 1-way ANOVA test with Dunnett's post-hoc test; ***p < 0.001 (left panel). Raji cells pre-stained with 1.5 µM CM-H2-DCFDA were incubated with 200 µM L-ASC, 0.5 µM AUR, or their combination. The intensity of green fluorescence of all living cells, gated based on SSC and FSC parameters, was assessed by flow cytometry at indicated time points. CAT (100 µg/ml) was added 30 min prior to addition of L-ASC and AUR to the indicated groups. The results are presented as fold over untreated control. Means of three independent experiments ± SD are presented. Statistical significance between each experimental group and the DMSO-treated control for each time-point was assessed using 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (middle panel). The viability of Raji cells incubated 48 h with the combination of 200 µM L-ASC and 0.5 µM AUR ± 100 µg/ml CAT was assessed by flow cytometry after PI staining. Bars present means of two independent experiments + SD (right panel).

Further, we investigated the mechanisms of L-ASC and AUR synergism utilizing a Raji cell line as a model. First, we compared the cytotoxic efficacy of L-ASC, D-ASC, and L-DHA in combination with AUR. As presented in Fig. 3A (middle panel), AUR similarly potentiated the effects of both L-ASC and D-ASC, despite the less efficient entry of D-ASC into Raji cells (Supplementary Fig. 9). The less efficient transport of D-ASC is in agreement with previously reported ascorbate stereo-selective uptake [28]. L-DHA utilizes different transporters to enter cells, mainly GLUT1, and following import is reduced to L-ASC by intracellular reductases [29]. Concordantly with abundant expression of GLUT1 on Raji cells [30], a 6 h incubation of the cells with L-DHA resulted in the significant intracellular accumulation of L-ASC (Supplementary Fig. 9). However, L-DHA in combination with AUR did not trigger any cytotoxic effects (Fig. 3A, middle panel). In addition, AUR enhanced the cytotoxicity of extracellular H2O2 generated by the addition of glucose oxidase (GOx) to the culture medium (Fig. 3A, right panel). All the above experiments suggest that AUR enhances the cytotoxicity of extracellularly-generated H2O2 and imply that in our in vitro settings the mechanism of cell death is different from the intracellularly-generated oxidative stress followed by GSH depletion, as reported by Yun at al. [10].

2.4. L-ASC in combination with AUR result in accumulation of H2O2 in cells and iron-dependent cytotoxicity

H2O2 is cell permeable and easily diffuses through membranes. To specifically measure intracellular levels of H2O2, we generated Raji cells genetically modified to express HyPer3, an H2O2 protein sensor [31]. In these cells, treated with L-ASC alone, the increase in intracellular H2O2 was almost undetectable, implying effective removal of H2O2. In contrast, the concurrent treatment with L-ASC and AUR led to a significant and persistent (up to 6 h) increase in intracellular H2O2, which was abolished by the addition of catalase (Fig. 3B, left panel). Similarly, only the L-ASC+AUR treatment triggered the massive and persistent accumulation of ROS measured with a cell-permeable CM-H2-DCFDA fluorescent probe, which detects general oxidative stress (Fig. 3B, middle panel). Catalase added to the culture medium fully rescued Raji cells from the combination cytotoxicity (Fig. 3B, right panel), further confirming H2O2 as a main trigger of the cell death.

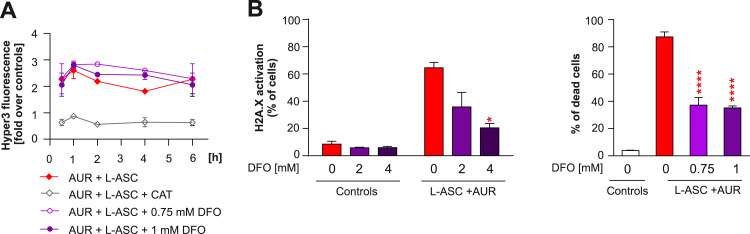

Not H2O2 itself, but rather its metabolites, such as hydroxyl radicals generated in Fenton reaction, are toxic to cells. Schoenfeld et al. reported the crucial role of intracellular iron in mediating the cytotoxic effects of L-ASC [7]. To address the role of intracellular iron in the efficacy of L-ASC+AUR, we pre-loaded Raji cells with an iron chelator deferoxamine (DFO) and subsequently treated with L-ASC+AUR in a fresh medium without DFO. First, we checked the effects of DFO pre-loading on H2O2 levels in HyPer3-modified Raji cells treated with L-ASC+AUR. As shown in Fig. 4A, DFO did not influence the intracellular levels of H2O2, indicating that pre-loading approach does not affect L-ASC-mediated H2O2 generation. However, elimination of intracellular iron with DFO significantly decreased oxidative DNA damage detected in Raji cells treated with L-ASC+AUR (Fig. 4B, left panel). Accordingly, the cytotoxicity of L-ASC+AUR was greatly diminished when Raji cells were pre-loaded with DFO (Fig. 4B, right panel). The above data reveal that L-ASC extracellularly generates H2O2, which selectively accumulates in AUR-treated cells. For the synergistic cytotoxic effects to occur, both H2O2 accumulation and intracellular iron are needed.

Fig. 4.

L-ASC and AUR combination results in iron-mediated oxidative damage and cytotoxicity. A. Raji-HyPer3 cells were pre-loaded for 1 h with indicated concentrations of deferoxamine (DFO), washed extensively with PBS, and treated with 200 µM L-ASC and 0.5 µM AUR. To evaluate intracellular H2O2 levels, the intensity of HyPer3 was assessed at indicated time points by flow cytometry. Means ± SD from two experiments (n = 4) normalized to untreated control are shown for each time point. B. Raji cells were pre-loaded with DFO as described in A. and treated with 200 µM L-ASC and 0.5 µM AUR. The H2A.X phosphorylation, a marker of DNA damage, was assessed upon 6 h of the incubation. Bars are means from three experiments + SD. Statistical significance was evaluated using 1-way ANOVA test with Tukey's correction in DFO-containing groups and AUR+L-ASC without DFO; *p < 0.05 (left panel). Raji cells were pre-loaded with DFO as described in A. and treated with 200 µM L-ASC and 0.5 µM AUR. PI staining was used to assess % of dead cells after 48 h of incubation. Bars are means from two experiments + SD (right panel). Statistical significance was evaluated using 1-way ANOVA test with Tukey's correction in DFO-containing groups and AUR+L-ASC without DFO; ****p < 0.0001.

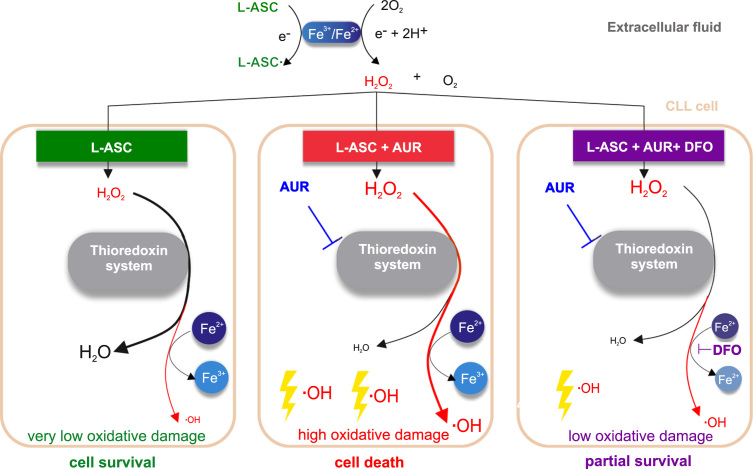

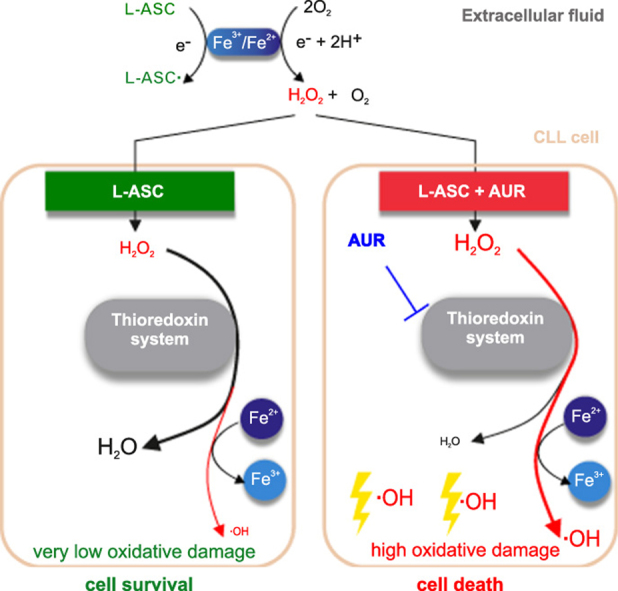

3. Conclusions

Collectively, our results indicate that selective anticancer activity of L-ASC can be enhanced by inhibition of TXN system-dependent H2O2 removal, in particular by inhibition of PRDX1. We show the key role of the PRDX-TXN-TXNRD antioxidant system in scavenging H2O2 in malignant B-cells. Moreover, we demonstrate that TXNRD inhibitor - AUR, an anti-rheumatic drug used for decades in patients, diminishes H2O2-scavenging capacity of malignant B-cells and potentiates L-ASC anticancer activity. The proposed mechanism of the synergistic cytotoxic effects of L-ASC and AUR, dependent on intracellular iron and Fenton reaction, is presented in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of a possible mechanism by which AUR augments L-ASC cytotoxicity in Fe2+-dependent manner. In extracellular fluid, L-ASC, in the presence of transition metal ions, generates H2O2, which enters the cell. In the absence of AUR, L-ASC is effectively removed by the TXN system, no oxidative damage occurs, and the cell survives (left panel). When the TXN system is blocked by AUR, H2O2 accumulates in the cell and, in the presence of Fe2+, generates highly reactive hydroxyl radicals, which lead to oxidative damage and cell death (middle panel). DFO chelates intracellular Fe2+, which impairs hydroxyl radical generation, relieves oxidative damage and results in partial cell survival (right panel).

The enhancement of pharmacological ascorbate anticancer activity by AUR was maintained in primary CLL co-cultures with stroma as well as in mice, indicating that redox-protective mechanisms of the microenvironment did not abolish this effect. Although the addition of AUR prolonged the survival of mice treated with pharmacological ascorbate, the effect on tumor growth in the murine model was moderate. However, in mice, as presented in Supplementary Table 1, and as had been shown before in different mice strains [32], after i.p. bolus injection, the peak of L-ASC in serum is transient and drops below 0.5 mM already after 2 h.

In contrast to mice, in humans pharmacological ascorbate can reach millimolar serum concentrations for over 7 h after 2 h-long intravenous infusions [33]. The results of clinical trials revealed that high doses of i.v. administered ascorbate are well tolerated and non-toxic, however, in monotherapy have no anticancer effect [33], [34]. In contrast, recent early-phase clinical trials indicate that pharmacological ascorbate at 1 g/kg dose improves chemo- and radiotherapy of gliomas and lung cancer [7], [35] and mitigates chemotherapy-induced side effects [8]. Our studies reveal that the anti-leukemic activity of L-ASC can be selectively improved with inhibition of H2O2-scavenging enzymes by AUR, which could be potentially beneficial for cancer patients. However, further preclinical in vivo studies are needed to elucidate if alternative modes of pharmacological ascorbate administration, resulting in more sustainable L-ASC levels in sera, will improve the efficacy of the combination of L-ASC and AUR. Providing promising results obtained in these studies, given that AUR is already used in the clinic and its safety profile is known, the efficacy of pharmacological ascorbate in combination with AUR could be worth investigating in leukemia and lymphoma patients.

4. Materials and methods

All of the methods are described in Supplementary information, which accompanies this paper on the Redox biology website https://www.journals.elsevier.com/redox-biology.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Polish National Science Centre grant 2016/21/B/NZ7/02041 (MF), European Commission Horizon 2020 Programme 692180-STREAMH2020-TWINN-2015 (JG). JAK is currently supported through Cancer Research UK Cambridge Centre Clinical Research Fellowship Programme at the University of Cambridge. AD is currently working at Department of Urology, Holycross Cancer Center, Kielce, Poland. We would like to acknowledge Rut Klinger, University College Dublin, for her help in generation of the plasmid for the overexpression of HyPer3 in Raji cells and prof. A Rosen from the University of Uppsala, Sweden, for kindly providing the CI cell line.

Acknowledgments

Declarations of interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.redox.2018.11.020.

Contributor Information

Agnieszka Graczyk-Jarzynka, Email: agnieszka.graczyk-jarzynka@wum.edu.pl.

Agnieszka Goral, Email: agnieszka.goral@wum.edu.pl.

Angelika Muchowicz, Email: angelika.muchowicz@wum.edu.pl.

Radoslaw Zagozdzon, Email: radoslaw.zagozdzon@wum.edu.pl.

Magdalena Winiarska, Email: mwiniarska@wum.edu.pl.

Malgorzata Bajor, Email: malgorzata.bajor@wum.edu.pl.

Klaudyna Fidyt, Email: klaudyna.fidyt@wum.edu.pl.

Julia Cyran, Email: js.cyran@student.uw.edu.pl.

Dimitar G. Efremov, Email: Dimitar.Efremov@icgeb.org.

Karolina Siudakowska, Email: karolina.siudakowska@wum.edu.pl.

Malgorzata Bobrowicz, Email: malgorzata.bobrowicz@wum.edu.pl.

Marta Klopotowska, Email: marta.klopotowska@wum.edu.pl.

Ewa Lech-Maranda, Email: ewamaranda@wp.pl.

Jakub Golab, Email: jakub.golab@wum.edu.pl.

Malgorzata Firczuk, Email: mfirczuk@wum.edu.pl.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- 1.German Nutrition Society New reference values for vitamin C intake. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015;67(1):13–20. doi: 10.1159/000434757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Q. Ascorbate in pharmacologic concentrations selectively generates ascorbate radical and hydrogen peroxide in extracellular fluid in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104(21):8749–8754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702854104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Q. Pharmacologic doses of ascorbate act as a prooxidant and decrease growth of aggressive tumor xenografts in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105(32):11105–11109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804226105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine M., Padayatty S.J., Espey M.G. Vitamin C: a concentration-function approach yields pharmacology and therapeutic discoveries. Adv. Nutr. 2011;2(2):78–88. doi: 10.3945/an.110.000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawada H. Phase I clinical trial of intravenous L-ascorbic acid following salvage chemotherapy for relapsed B-cell non-hodgkin's lymphoma. Tokai J. Exp. Clin. Med. 2014;39(3):111–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monti D.A. Phase I evaluation of intravenous ascorbic acid in combination with gemcitabine and erlotinib in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29794. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoenfeld J.D. O2(-) and H2O2-mediated disruption of Fe metabolism causes the differential susceptibility of NSCLC and GBM cancer cells to pharmacological ascorbate. Cancer Cell. 2017;31(4):487–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.02.018. (e8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma Y. High-dose parenteral ascorbate enhanced chemosensitivity of ovarian cancer and reduced toxicity of chemotherapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014;6(222):222ra18. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mingay M. Vitamin C-induced epigenomic remodelling in IDH1 mutant acute myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia. 2018;32(1):11–20. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yun J. Vitamin C selectively kills KRAS and BRAF mutant colorectal cancer cells by targeting GAPDH. Science. 2015 doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Q. Pharmacologic ascorbic acid concentrations selectively kill cancer cells: action as a pro-drug to deliver hydrogen peroxide to tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102(38):13604–13609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506390102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Espinosa-Diez C. Antioxidant responses and cellular adjustments to oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2015;6:183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graczyk-Jarzynka A. New insights into redox homeostasis as a therapeutic target in B-cell malignancies. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2017;24(4):393–401. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorrini C., Harris I.S., Mak T.W. Modulation of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013;12(12):931–947. doi: 10.1038/nrd4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doskey C.M. Tumor cells have decreased ability to metabolize H2O2: implications for pharmacological ascorbate in cancer therapy. Redox Biol. 2016;10:274–284. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shatzer A.N. Ascorbic acid kills Epstein-Barr virus positive Burkitt lymphoma cells and Epstein-Barr virus transformed B-cells in vitro, but not in vivo. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2013;54(5):1069–1078. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.739686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li C. Over-expression of Thioredoxin-1 mediates growth, survival, and chemoresistance and is a druggable target in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2012;3(3):314–326. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trzeciecka A. Dimeric peroxiredoxins are druggable targets in human Burkitt lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2015 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang W. Stromal control of cystine metabolism promotes cancer cell survival in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14(3):276–286. doi: 10.1038/ncb2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klossowski S. Studies toward novel peptidomimetic inhibitors of thioredoxin-thioredoxin reductase system. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55(1):55–67. doi: 10.1021/jm201359d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffith O.W., Meister A. Potent and specific inhibition of glutathione synthesis by buthionine sulfoximine (S-n-butyl homocysteine sulfoximine) J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254(16):7558–7560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhee S.G., Kil I.S. Multiple functions and regulation of mammalian peroxiredoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017;86:749–775. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiskus W. Auranofin induces lethal oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress and exerts potent preclinical activity against chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2014;74(9):2520–2532. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Celegato M. Preclinical activity of the repurposed drug auranofin in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2015;126(11):1394–1397. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-07-660365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dai B. KEAP1-dependent synthetic lethality induced by AKT and TXNRD1 inhibitors in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73(17):5532–5543. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dickinson B.C., Huynh C., Chang C.J. A palette of fluorescent probes with varying emission colors for imaging hydrogen peroxide signaling in living cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132(16):5906–5915. doi: 10.1021/ja1014103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yourga F., Esselen W., Fellers C. Some antioxidant properties of D-ISO ascorbic acid and its sodium salt. J. Food Sci. 1944;486:188–196. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Franceschi R.T., Wilson J.X., Dixon S.J. Requirement for Na(+)-dependent ascorbic acid transport in osteoblast function. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268(6 Pt 1):C1430–C1439. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.6.C1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linster C.L., Schaftingen E. Van. Vitamin C. Biosynthesis, recycling and degradation in mammals. FEBS J. 2007;274(1):1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malenda A. Statins impair glucose uptake in tumor cells. Neoplasia. 2012;14(4):311–323. doi: 10.1593/neo.12444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bilan D.S. HyPer-3: a genetically encoded H(2)O(2) probe with improved performance for ratiometric and fluorescence lifetime imaging. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8(3):535–542. doi: 10.1021/cb300625g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verrax J., Calderon P.B. Pharmacologic concentrations of ascorbate are achieved by parenteral administration and exhibit antitumoral effects. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;47(1):32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoffer L.J. Phase I clinical trial of i.v. ascorbic acid in advanced malignancy. Ann. Oncol. 2008;19(11):1969–1974. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nielsen T.K. Weekly ascorbic acid infusion in castration-resistant prostate cancer patients: a single-arm phase II trial. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2017;6(3):517–528. doi: 10.21037/tau.2017.04.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao H. The synergy of Vitamin C with decitabine activates TET2 in leukemic cells and significantly improves overall survival in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Res. 2018;66:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary material