Abstract

In many Gram-negative bacteria, the type 2 secretion system (T2SS) plays an important role in virulence because of its capacity to deliver a large amount of fully folded protein effectors to the extracellular milieu. Despite our knowledge of most T2SS components, the mechanisms underlying effector recruitment and secretion by the T2SS remain enigmatic. Using complementary biophysical and biochemical approaches, we identified here two direct interactions between the secreted effector CbpD and two components, XcpYL and XcpZM, of the T2SS assembly platform (AP) in the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Competition experiments indicated that CbpD binding to XcpYL is XcpZM-dependent, suggesting sequential recruitment of the effector by the periplasmic domains of these AP components. Using a bacterial two-hybrid system, we then tested the influence of the effector on the AP protein–protein interaction network. Our findings revealed that the presence of the effector modifies the AP interactome and, in particular, induces XcpZM homodimerization and increases the affinity between XcpYL and XcpZM. The observed direct relationship between effector binding and T2SS dynamics suggests an additional synchronizing step during the type 2 secretion process, where the activation of the AP of the T2SS nanomachine is triggered by effector binding.

Keywords: protein-protein interaction, protein secretion, type II secretion system (T2SS), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), protein assembly, protein complex, protein export, protein sorting, effector recognition, type 2 secretion, Xcp, Gsp

Introduction

Type IV filament (Tff)3 nanomachines are membrane-embedded macromolecular complexes organized around a characteristic helical pilus-like structure emerging from an assembly platform at the cytoplasmic membrane (1). Tffs are widespread in prokaryotes where they fulfill diverse cellular functions, in particular the type 2 secretion system (T2SS) that is found in many pathogenic Gram-negative proteobacteria (2). It is dedicated to the secretion of large folded periplasmic exoproteins via a piston-like apparatus called the secreton. Secretons are constituted by 12–15 different components organized into three subcomplexes: the outer-membrane pore belonging to the secretin family, the assembly platform (AP) or motor of the system, and the typical pseudopilus emerging from the AP up to the secretin pore (for the most recent reviews, see Refs. 3 and 4).

T2SS secretins are homomultimers assembled into a giant gated β-barrel pore in the outer membrane connected to the AP by an N-terminal periplasmic extension (5–7). The Tff-specific structure of the T2SS is called the pseudopilus. It is constituted by the helical assembly of the five pseudopilins of the system. Chronologically, the four minor pseudopilins, GspHIJK, are first assembled by the AP and thus form the head of the structure. This step is followed by the addition, from the bottom of the filament, of the major pseudopilin GspG into a pseudopilus (8–11). Pseudopilus assembly is energized and promoted by the AP, which is constituted by the oligomeric assembly of four membrane proteins, including the three bitopic proteins GspC, GspL, and GspM and the integral membrane protein GspF. The energy for pseudopilus assembly is provided by the cytoplasmic ATPase, GspE. The four membrane components of the AP interact through a complex dynamic network involving both soluble and transmembrane (TM) domains (12–17). GspC possesses an N-terminal TM domain anchoring the protein into the inner membrane (IM). GspC's TM domain is followed by a large C-terminal periplasmic domain composed of the HR and coiled-coil (or PDZ) subdomains. GspC self-dimerizes through its TM subdomain (13) and interacts with the N-domain of the secretin via its HR subdomain (18, 19), thus connecting the outer and inner membrane components of the secreton. The GspL and GspM AP components have a similar architecture with a TM domain followed by a globular C-terminal periplasmic domain with a ferredoxin-like fold (15, 16). These periplasmic domains self-interact but also interact with each other as well as with the periplasmic domain of GspC (14, 17). In contrast to GspM and GspC, GspL harbors an additional N-terminal cytoplasmic domain presenting structural homology with actin-like ATPases (20). This domain is, together with the integral inner membrane protein GspF, involved in the recruitment of the ATPase GspE at the secretion site (21–26). Further activation of GspE requires interactions with phospholipids (27). It has been proposed that upon sensing of a signal, the AP interaction network is displaced to ensure proper functioning of the system possibly through intrinsically disordered domains (4). This includes signal transduction across the IM between the periplasmic and cytoplasmic sides of the secreton (4, 28). Such transmembrane dynamic signaling has also been reported in the archetypal Tff member, the type IV pilus (29).

Type 2 secretion is a two-step process during which effectors are first exported across the IM by the Sec or Tat systems (30, 31). Then, the folded periplasmic effectors are recognized and transported to the extracellular milieu by the secreton (32). How T2SS effectors are specifically recognized by the secreton in the periplasmic soup remains an open question. In contrast to other secretion systems and despite intense research, no common secretion signal has been identified in T2SS effectors. However, several direct interactions have been described between secreted effectors and the secretin GspD, the AP component GspC, and the pseudopilus tip (24, 33–36). It is accepted that effector recognition and recruitment are performed by GspC (17, 24, 34, 37) followed by its transfer into the secretin vestibule before being extruded out of the cell upon contact with the pseudopilus tip (32). A direct interaction between effectors and GspC HR and PDZ subdomains (24, 37) suggests that effector recruitment involves multiple contacts with GspC. In addition, it has been shown that the TMHR domain of GspC is indirectly involved in effector recognition specificity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (17). Various GspD N-domains are also involved in effector binding, depending on the organism (5, 24, 33, 34, 36). Finally, a direct interaction has also been reported between the effector and the pseudopilus tip constituted by the periplasmic domains of GspHIJK (34).

Here, we report that in addition to interacting with GspC, the secretin, and the pseudopilus tip, the T2SS secreted effector also interacts specifically with the periplasmic domains of GspM and GspL inner membrane components of the AP. We further show that these periplasmic interactions trigger conformational changes in the AP that may lead to ATPase activation and pseudopilus assembly. We thus propose that these newly discovered interactions constitute an additional step of the T2SS secretion process, synchronizing effector loading and pseudopilus assembly.

Results

Direct and specific interaction between the Xcp effector CbpD and XcpYL periplasmic domain (XcpYLp)

Our T2SS working model is the Xcp system of P. aeruginosa where 11 different components are named P–Z with the species-specific prefix Xcp. Because protein letters are specific to the Pseudomonas genus, we will systematically refer to the general Gsp nomenclature using a subscript; i.e. the GspL homolog in P. aeruginosa is named XcpYL.

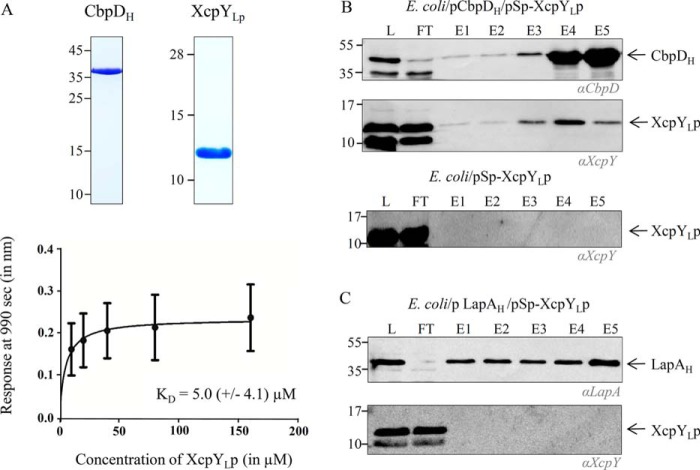

We previously showed by surface plasmon resonance that the purified periplasmic domains of the secretin XcpQD, the AP component XcpPC, and the pseudopilus tip quaternary complex (XcpUHVIWJXK) directly bind secreted effectors, thus allowing us to propose an integrated model of effector recognition and transport by the T2SS (34). To have a better view of the Xcp/effector interactome in the periplasm, we tested the interaction between the secreted effector CbpD and the periplasmic domains of the bitopic AP component XcpYL (XcpYLp). We used biolayer interferometry (BLI), an in vitro protein–protein interaction technique similar to surface plasmon resonance. XcpYLp and CbpD proteins were produced and purified by consecutive affinity and size-exclusion chromatography steps (Fig. 1A), following the procedure used previously (34). CbpD was then biotinylated and immobilized on the sensor tip to be used as bait, and interaction experiments were performed in triplicate with purified XcpYLp used as prey, following the protocol described under “Experiment procedures.” The graph, presented in Fig. 1A and reporting the response (nm) as a function of the XcpYLp concentration (μm), was used to measure the dissociation constants (KD). BLI data reveal that XcpYLp directly interacts with the secreted effector CbpD with a relatively low KD of 5.0 μm.

Figure 1.

Specific XcpYL/T2SS effector direct interaction. A, characterization of XcpYLp/CbpD binding using BLI. Samples of purified XcpYLp and CbpDH used in BLI experiments were analyzed by 15% SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining (top). The graph reporting the BLI response (nm) as a function of XcpYp concentration (10–160 μm) from three independent experiments was used to calculate the indicated apparent KD. Each data point (mean ± S.D.) is the result from triplicate experiments. Error bars indicate S.D. B and C, copurification and immunoblotting experiments of coproduced XcpYLp with His-tagged CbpD (CbpDH) (B) or His-tagged LapA (LapAH) (C). L, loading material; FT, flow-through; E1–E5, elution fractions. Antibodies used for XcpYL, CbpD, and LapA detection are indicated in italic below each immunoblot.

To validate this in vitro interaction between CbpD and XcpYL in a more biological context, we set up and performed an in vivo copurification experiment. To reconstitute the natural periplasmic context of the interaction in the absence of the other Xcp T2SS components and secreted effectors, the two partners were produced in the periplasm of the heterologous host Escherichia coli. When produced in E. coli, CbpD naturally accumulates in the periplasm because of its Sec signal peptide (Sp). The second partner, XcpYLp, was artificially targeted to the periplasm by the addition of LasB Sp to its N terminus (Sp-XcpYLp). We first tested protein production under inducing conditions and verified the proper periplasmic localization of CbpD and XcpYLp (Fig. S1). The soluble cell fraction of the E. coli/pCbpDH/pSp-XcpYLp strain grown under inducing conditions was extracted and analyzed by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC). The copurification experiments shown in Fig. 1B indicate that XcpYLp is coeluted with the histidine-tagged CbpDH, used here as bait, thus supporting the direct interaction found by BLI between the two proteins. The observation (Fig. 1B, bottom) that XcpYLp is not recovered in the elution fractions in the absence of CbpDH excludes a nonspecific affinity of XcpYLp for the IMAC resin.

We then took advantage of the presence of two independent T2SSs in P. aeruginosa, the Xcp and Hxc systems, each secreting their own effectors (38), to test the effector specificity of this newly characterized interaction. We performed in vivo cross-copurification experiments using E. coli strains coproducing the Hxc effector LapAH together with XcpYLp (E. coli/pLapAH/pSp-XcpYLp). Soluble protein lysates obtained under inducible conditions were analyzed by IMAC (Fig. 1C), and we noticed that XcpYLp did not copurify with the heterologous Hxc effector. These data confirms that, as is also the case for XcpQD, XcpPC, and the pseudopilus tip (34), the interaction of XcpYL with its cognate effector is system-specific.

Direct interaction between the Xcp effector CbpD and the periplasmic domain of XcpZM

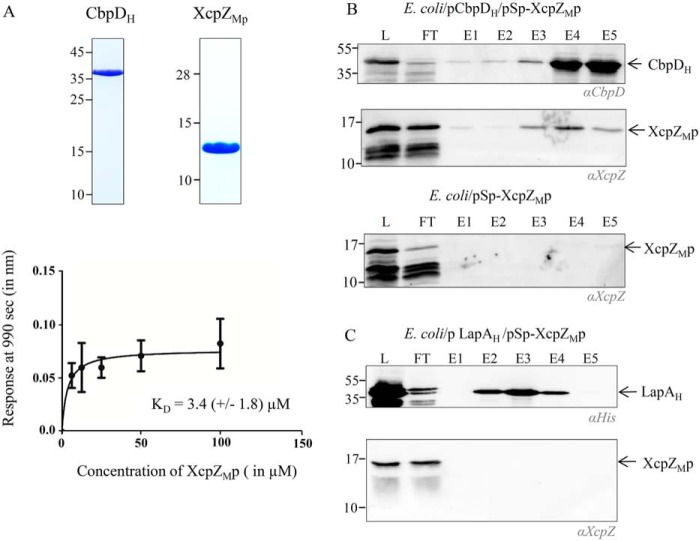

To further characterize the Xcp/effector periplasmic interactome, we next tested whether CbpD interacts with the periplasmic domain of the inner membrane component XcpZM (XcpZMp). XcpZM corresponds to the only periplasmic globular domain of the secreton not yet tested for interaction with the secreted effector. As above for XcpYL, we combined complementary in vitro and in vivo protein–protein interaction experiments to investigate the interaction between XcpZMp and secreted effectors. The BLI experiment using purified CbpD as bait and XcpZMp as prey was done in triplicate and showed a direct interaction between the two proteins, with a KD of 3.4 μm (Fig. 2A). This in vitro interaction was confirmed by a cross-linking experiment using the short cross-linking agent bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)glutarate (BS2G). Analysis of the cross-linking products by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining showed a protein complex specifically recovered in the presence of the two partners and the cross-linker (Fig. S2) with a molecular weight corresponding to a heterodimer composed of XcpZMp and CbpD. This was confirmed by immunoblotting, which showed that XcpZMp and CbpD are both present in the corresponding complex.

Figure 2.

Specific XcpZM/T2SS effector direct interaction. A, characterization of XcpZMp/CbpD binding using BLI. Samples of previously purified CbpDH used in the experiment presented Fig. 1 and newly purified XcpZMp were analyzed by 15% SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining and used in BLI experiments. The graph reporting the BLI response (nm) as a function of XcpZp concentration (6.25–100 μm) from three independent experiments was used to calculate the indicated apparent KD. Each data point (mean ± S.D.) is the result from triplicate experiments. Error bars indicate S.D. B and C, copurification and immunoblotting experiments of coproduced XcpZMp with His-tagged CbpD (CbpDH) (B) or His-tagged LapA (LapAH) (C). L, loading material; FT, flow-through; E1–E5, elution fractions. Antibodies used for XcpZM, CbpD, and LapA detection are indicated in italic below each immunoblot.

Furthermore, the interaction between XcpZMp and CbpD was tested and validated by in vivo copurification experiments. To do this, we constructed an E. coli strain producing in its periplasm CbpDH and XcpZMp (E. coli/pCbpDH/pSp-XcpZMp) and proceeded with IMAC copurification experiments following the procedure used for XcpYLp.

The analysis of the eluted fractions by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with anti-CbpD and anti-XcpZM antibodies shows the specific coelution of XcpYLp by CbpDH (Fig. 2B). As for XcpYLp, the XcpZMp/effector interaction is Xcp T2SS-specific because the Hxc effector LapAH does not copurify the Xcp GspM component XcpZMp (Fig. 2C). Altogether, the presently discovered direct interactions between the secreted effector and the globular periplasmic domains of XcpZM and XcpYL reveal for the first time a direct and specific interaction between secreted effector and components of the T2SS assembly platform.

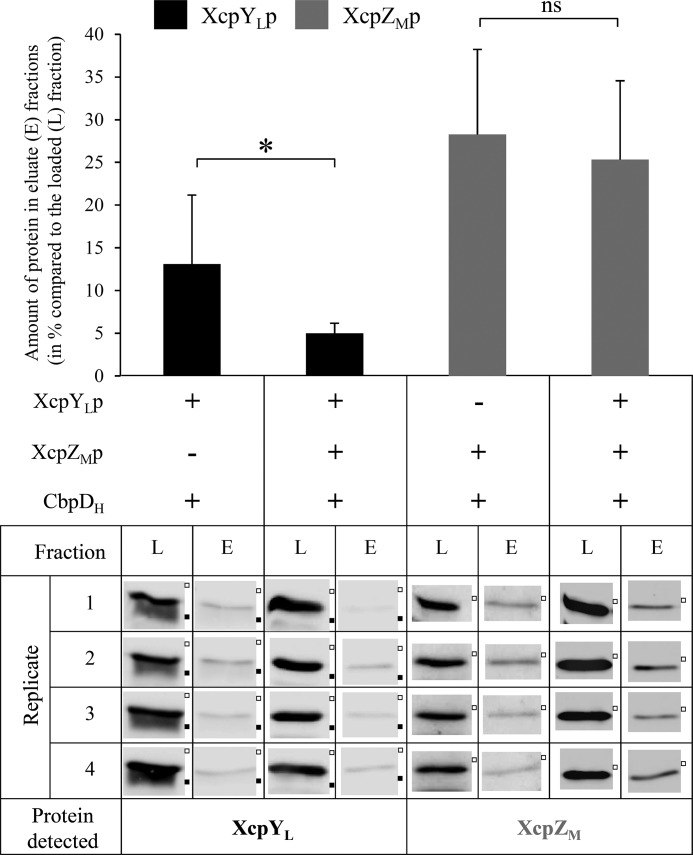

Competition between XcpYLp and XcpZMp for binding to CbpD

Protein–protein interaction data revealed that the AP components XcpYL and XcpZM interact directly with the effector through their periplasmic domains, which raises to five the number of Xcp periplasmic domains or complexes that directly and specifically interact with secreted effectors. In all cases, interaction affinities between T2SS components and the secreted effector are in the μm range, in agreement with their transiency during the secretion process. We attempted to better understand the CbpD/XcpYLp/XcpZMp interactome by evaluating possible competition effects thanks to the multiple coexpression capacity of our in vivo periplasmic reconstitution effector/Xcp interactome assay. We therefore quantitatively compared the copurification levels of XcpYLp and XcpZMp with CbpDH in the presence or absence of the other CbpD interactant. Hence, the soluble cell lysates of the E. coli strains coproducing CbpDH with XcpYLp, XcpZMp, or XcpYLp together with XcpZMp were generated in quadruplicates and analyzed by IMAC for XcpZMp and XcpYLp copurification (Fig. 3). Although the proportion of XcpZMp copurified with CbpD is unchanged with or without coproduction of XcpYLp (Fig. 3, gray bars and corresponding immunoblots), a statistically significant reduction of XcpYLp binding to CbpD was observed in the presence of XcpZMp (Fig. 3, black bars and corresponding immunoblots). This competition experiment suggests that, during the secretion process, the secreted effector interacts sequentially with XcpYL and XcpZM.

Figure 3.

XcpZMp/XcpYLp binding competition on CbpD. Shown is quantification of CbpD-bounded XcpYLp or XcpZMp in the eluted fractions (E) compared with their amount in the loaded material (L) in the presence or absence of the second partner, XcpYLp or XcpZMp. The immunodetected bands of XcpYLp and XcpZMp for each loaded (L) and eluted (E) fraction of each replicate of the three copurification experiments are also presented. Molecular mass markers of 10 (■) and 17 kDa (□) are indicated on the right. ns, for nonsignificant; *, p value <0.05. Error bars indicate S.D.

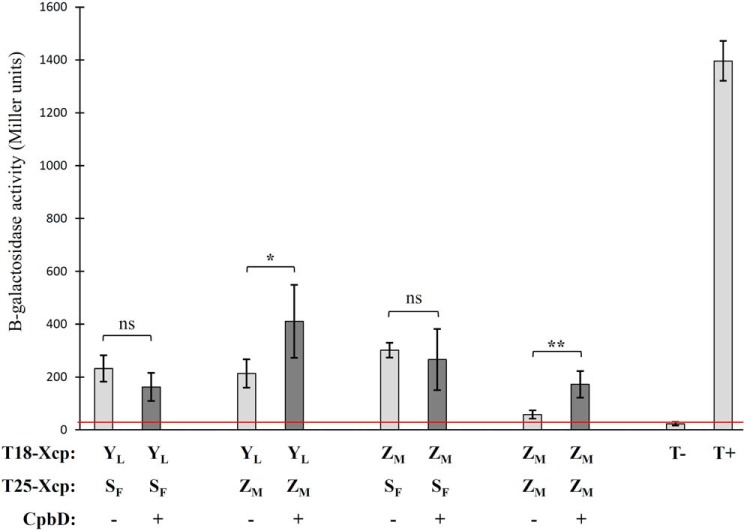

CbpD effector triggers XcpZM dimerization and increases XcpZM/YL interaction

The above data indicate that both XcpYL and XcpZM interact with the secreted effector through their periplasmic domains. To understand the possible consequences of such interactions on the global AP interactome within the secreton, we used the bacterial adenylate cyclase two-hybrid (BACTH) method developed by Karimova et al. (39). In this technique, proteins of interest are coexpressed in an E. coli cya mutant (BTH101) as fusions with one of the two fragments (T18 and T25) from the catalytic domain of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase. Interaction of two-hybrid proteins results in a functional complementation between T18 and T25, leading to cAMP synthesis and transcriptional activation of the lactose operon that can be easily detected by β-gal activity measurement. We chose this technique because it is particularly well adapted to quantify interactions between membrane proteins (40). Full-length XcpYL, -ZM, and -SF proteins were therefore fused to the T18 and/or T25 domains via their N termini (see “Experimental procedures”).

We first evaluated the heterodimerization capacities of different AP components by measuring β-gal activity of the three combinations, T18-YL/T25-SF, T18-YL/T25-ZM, and T18-ZM/T25-SF, and comparing it with positive and negative controls (Fig. 4, light gray bars). Results indicate that full-length XcpYL directly interacts with XcpZM. A similar observation, using the same approach, has already been reported in different T2SSs (10, 11, 14). Interestingly, we also found that XcpSF, the polytopic IM component of the AP, directly interacts with XcpYL and XcpZM, thus confirming the physical interconnection between components of the AP. In addition and as previously observed by Lallemand et al. (14), full-length XcpZM does not self-dimerize (or self-dimerization is very weak) when produced alone in the E. coli membrane (Fig. 4). This negative result is not due to nonfunctional fusion proteins because both T18/25 XcpZM fusions give positive signals when combined with XcpYL and XcpSF partners (Fig. 4). This result contrasts with the homodimerization property of the periplasmic domain of XcpZM revealed by size-exclusion chromatography (Fig. S3) and suggests that XcpZM periplasmic homodimerization might be prevented by its transmembrane domain.

Figure 4.

Effect of CbpD on the AP interactome measured by BACTH. Different combinations of T18/T25 reporter domains fused to the N-domains of full-length Xcp AP components were evaluated by BACTH in the presence or absence of the Xcp secreted effector CbpD. As a positive control (T+), we used the couple T18-Tol/T25-Pal (46). The value of the negative control (T−) corresponds to the mean of all T18/T25 combinations containing Xcp constructs against T18-Tol/T25-Pal. Results are expressed in Miller units of β-gal activity and are the mean ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. Error bars indicate S.D. The red line indicates the background β-gal activity measured in the negative control. ns, nonsignificant; *, p value <0.05; **, p value <0.01.

We then decided to challenge this AP interactome in the presence of the T2SS effector CbpD (Fig. 4, dark gray bars). CbpD was therefore coproduced in the periplasm of the BTH101 strains producing the various Xcp T18/T25 pairs. No difference was seen for the pairs involving XcpSF, indicating that CbpD binding to XcpYL has no significant effect on the XcpYL/SF interaction. In contrast, a statistically significant increase in β-gal activity was measured in the presence of CbpD for the T18-ZM/T25-ZM pair, showing that the presence of CbpD triggers XcpZM homodimerization, possibly through their periplasmic domains (Fig. S3). Similarly, CbpD coproduction was also performed with the T18-YL/T25-ZM pair. In this case, the presence of the effector significantly increased the β-gal levels, revealing a significant strengthening of the interaction between XcpYL and XcpZM in the presence of the secreted effector. Those findings indicate that the presence of the effector triggers structural rearrangements of the AP, thus suggesting a possible synchronization between effector arrival and activation of the system.

Discussion

Effector recognition by the T2SS remains enigmatic because no common secretion signal has been identified in the numerous effectors reported so far. All attempts to identify the secretion signal of the T2SS have converged to the existence of a still unknown conformational signal, in agreement with the folded state of the effectors prior to recognition by the secreton (41). Here, we focused on the Xcp T2SS of P. aeruginosa, which secretes at least 19 different exoproteins, to study effector recognition and transport. Based on the identification of a set of direct periplasmic interactions between secreted effectors and components of the three subcomplexes of the secreton, we previously proposed a model of effector recognition and transport by the T2SS (34). In this model, the substrate is recognized by the secreton peripheral component XcpPC and then transferred into the secretin (XcpQD) vestibule to be expelled out of the secretin pore upon contact with the pseudopilus tip (XcpUHVIWJXK). In the present study, we completed the Xcp/effector periplasmic interactome by testing XcpYL and XcpZM, the last two Xcp components harboring a periplasmic domain not included in previous studies. We applied two complementary protein–protein interaction approaches and found that the two AP components directly and specifically interact with the secreted effector CbpD through their periplasmic domains. This brings to five the number of Xcp partners physically and specifically encountered by the effector during the secretion process, thus indicating a system-specific route for substrate recruitment and transport all along the Xcp T2SS secreton.

IMAC experiments revealed a competition between XcpYL and XcpZM for the effector, suggesting interaction sequentiality. However, it is difficult at this stage to establish an order for these two interactions and propose a hierarchical positioning in the previous T2SS secretion model. Our data nevertheless show for the first time a direct involvement of both GspL and GspM in substrate recognition.

We further evaluated the possible consequences of these new interactions on the T2SS by addressing their impact on AP dynamics. Using BACTH as a quantitative protein–protein interaction technique, we first established the interactome network among the three AP components, XcpYL, XcpZM, and XcpSF. We then found that XcpZM oligomerization and XcpYL/XcpZM heterodimerization are, respectively, triggered and strengthened upon effector binding. Those important observations constitute the first experimental evidence of effector-mediated conformational changes of the T2SS AP components, suggesting a possible synchronization between effector arrival and activation of the system. One possible type of activation mediated by substrate binding was described in a recent report by Lallemand et al. (14). In this work, using an elegant combination of in vivo protein–protein interaction and cross-linking experiments, the authors showed the molecular details of the dynamic interplay between full-length GspL and GspM. In their model, upon sensing an unknown signal, the interactions between GspL and GspM periplasmic domains shift from homo- to heterodimeric, mediating coordinated shifts or rotations of their cognate TM domains. We propose that the dynamic interplay leading to signal transduction from the periplasm to the cytoplasm is triggered by effector binding on the GspM and/or GspL periplasmic domain. It would be interesting to localize the effector-binding domains in XcpYL and XcpZM and their possible overlap with the ferredoxin-like domains of GspL and GspM directly involved in the dynamic interplay.

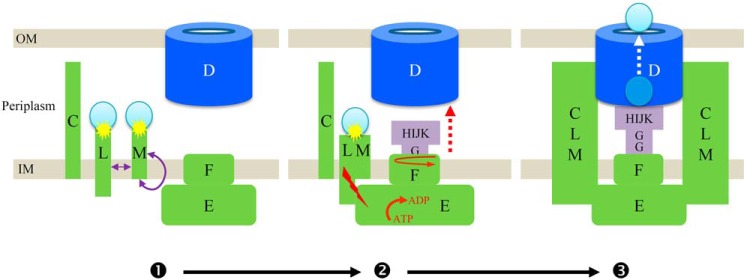

The next obvious question brought by our observations is what is the target of the signal transduced from the periplasm to the cytoplasm? A possible scenario, elaborated from the numerous interactions reported between the cytoplasmic domain of GspL and its partner, the ATPase GspE, was recently proposed by Gu et al. (4). Taking into account that activation of the ATPase necessitates an interaction between membrane lipids and the GspL's segment adjacent to the TM domain (27), the authors propose that activation of the ATPase could be mediated by a displacement of GspL in the inner membrane, itself induced by the transmembrane signal generated by effector binding in the periplasm. Therefore, considering that activation of the ATPase mediates pseudopilus assembly (42, 43), we propose that effector binding on the periplasmic domains of GspL and GspM triggers pseudopilus assembly, thus synchronizing this late step with effector arrival in the machinery. Therefore, an additional effector-sensing step, coupled with pseudopilus assembly, can be added to our model of effector recognition and transport by the T2SS (Fig. 5). Whether this effector sensing-step mediated by GspL and GspM is linked with their direct involvement in pseudopilus assembly (10, 43) remains to be determined.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the effector-sensing step mediated by XcpYL/ZM during secretion process by T2SS. ❶, effector (blue sphere) binding to the periplasmic domains of GspLY (L) and GspMZ (M) induces their homo- and/or hetero-oligomerization (purple arrows). ❷, the effector-mediated gathering of GspMZ and GspLL generates a transmembrane signal (red flash) triggering GspER (E) activation (ATP to ADP) and pseudopilus (GspGTHUIVJWKX (GHIJK)) assembly and elongation (dashed red arrows). ❸, the growing pseudopilus interacts with the effector, which first transfers it inside the vestibule of the secretin and then leads to its translocation in the extracellular milieu. Also represented on this cartoon are the secretin connector GspCP (C) and the polytopic AP component GspFS (F), which is involved in pseudopilus assembly upon cycles of GspER-mediated rotation (circular red arrows).

Further investigations are now required to understand, at the molecular level, the chronology of the effector/XcpYL and effector/XcpZM interactions and the effectors' subsequent transition into the secretin vestibule as well as the structural basis of the transmembrane signal transduction. In this respect, interestingly, the XcpYL periplasmic domain presents structural homology with proteins harboring the Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) domain. These PAS domains are present in all three domains of life and are involved in signaling and transmembrane signal transduction, such as in the bacterial two-component systems (44). This structural homology supports the sensing properties of GspL, which may play an important role in T2SS function.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains and plasmids

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Bacterial strain and plasmids used in this study

| Strain and plasmids | Genotype/characteristics | Origin/Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| BL21 (DE3) | fhuA2 [lon] ompT gal (λ DE3) [dcm]λ DE3 λ sBamHIo ΔEcoRI-B int:: (lacI::PlacUV5::T7 gene1) | Lab collection |

| TG1 | supE, hsdΔR, thiΔ (lac-proAB), F′ (traD36, proAB+, lacIq, lacZΔM15) | Lab collection |

| BTH101 | F−, cya-99, araD139, galE15, galK16, rpsL1 (Strr), hsdR2, mcrA1, mcrB1 | Lab collection |

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| PAO1 | Clinical isolate, reference wildtype strain | Lab collection |

| PAO1 D40ZQ | PAO1 reference with xcp operon deletion | Lab collection |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCDFDuet-1 | SmR, 2 MCS, PT7, Ori CDF | Novagen |

| pETDuet-1 | ApR, 2 MCS, PT7, Ori f1 | Novagen |

| pET22b | ApR, PT7, Ori f1, pelB cloning sequence | Novagen |

| pSp-XcpYLp | pCDFDuet carrying sp-xcpYLp gene in MCS2 | This study |

| pSp-XcpZMp | pCDFDuet carrying sp-xcpZMp gene in MCS2 | This study |

| pSp-XcpYLp-Sp-XcpZMp | pCDFDuet carrying sp-xcpYLp in MCS2 and sp-xcpZMp in MCS1 | This study |

| pCbpDH | pETDuet carrying cbpDH gene | This study |

| pLapAH | pETDuet carrying lapAH gene | Lab collection |

| pLIC07 | pET-28a + derivative vector for Trx translational fusions KmR | Bio-Xtal |

| pLIC-XcpYLp | pLIC07 carrying xcpYLp | This study |

| pLIC-XcpZMp | pLIC07 carrying xcpZMp | This study |

| pT7.5-CbpDH | pT7.5 carrying cbpDH gene | 47 |

| pJN105 | GmR, PBAD, Ori pBR | 48 |

| pJN105-CbpD | pJN105 carrying cbpD | This study |

| pKT25 | KmR, PLac, Ori 15A, MCS in the 3′ end of T25 | 40 |

| pKNT25 | KmR, PLac, Ori 15A, MCS in the 5′ start of T25 | 40 |

| pUT18C | ApR, PLac, Ori ColE1, MCS in the 3′ end of T18 | 40 |

| pUT18 | ApR, PLac, Ori ColE1, MCS in the 5′ start of T18 | 40 |

| pUT18C-XcpYL | pUT18C carrying 18-xcpYL | This study |

| pUT18C-XcpZM | pUT18C carrying 18-xcpZM | This study |

| pKT25-XcpZfl | pKT25 carrying 25-xcpZM | This study |

| pKT25-XcpSfl | pKT25 carrying 25-xcpSF | This study |

| pKT25-Tol | pKT25 carrying 25-tolB gene | E. Bouveret |

| pUT18C-Pal | pUT18C carrying 18-pal gene | E. Bouveret |

DNA manipulation

Plasmid preparation, DNA purification, gel extraction, and PCR product purification were performed using appropriate Macherey Nagel kits. Restriction enzymes, DNA polymerase, and other molecular biology reagents were purchased from New England Biolabs or Promega. The high-fidelity polymerase Q5 (Biolabs) was used for PCR amplification. The list of oligonucleotides (synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc.) used for cloning is provided in Table 2. To construct the BACTH plasmids, the xcp genes were PCR-amplified using corresponding primers and cloned into pKT25 and pUT18C vectors using the SLIC method between BamHI and EcoRI sites. To construct the expression plasmids for heterologous reconstitution, the xcpYL and xcpZM genes were PCR-amplified using corresponding primers and cloned into the pCDFDuet vector using the SLIC method or digestion ligation methods between NcoI and SalI (MCS1) sites for XcpZMp or NdeI and EcoRV (MCS2) sites for XcpYLp. The CbpDH gene was subcloned from pT7.5 vector to pETDuet vector using the EcoRI site. All plasmids were sequenced by GATC Co.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligo | Sequence (5′ → 3′) | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| OSM-86 | AGGAGATATACCATGAAATACCTGCTGCCG | sp-lasB for MCS1 up |

| OSM-87 | GCCGGGCGGGCCATCGCCGGCTGGGC | sp-lasB for MCS1 down |

| OSM-88 | CGATGGCCCGCCCGGCCGAGCGCCAT | xcpZMp for MCS1 up |

| OSM-91 | CCGCAAGCTTGTCGACTCACTCGACCCGCAGGC | xcpZMp for MCS1 down |

| OSM-62 | AAGGAGATATACATATGAAATACCTGCTGCC | sp-lasB for MCS2 up |

| OSM-63 | CAGGCCTGGGCCATCGCCGGCTGGGC | sp-lasB for MCS2 down |

| OSM-64 | CGATGGCCCAGGCCTGGCAGTTGCAG | xcpYLp for MCS2 up |

| OSM-47 | GCGTGGCCGGCCGATATCTCAACCTCCTATCACCAGGC | xcpYLp for MCS2 down |

| OSM-116 | CCAATCAATGGAGACCCAGGCCTGGCAGTTGCAG | xcpYLp for pLIC07 |

| OSM-117 | GTATCCACCTTTACTGGAGACCTCAACCTCCTATCACC | xcpYLp for pLIC07 |

| OSM-118 | CCAATCAATGGAGACCCGCCCGGCCGAGCGC | xcpZMp for pLIC07 |

| OSM-119 | GTATCCACCTTTACTGGAGACCTCACTCGACCCGCAGGCTC | xcpZMp for pLIC07 |

| XcpYL-pUT18C-F | CCCGGATCCCATGAGTGGAGTGAGTGCGCTGTTCC | xcpYL for pUT18C |

| XcpYL-pUT18C-R | GGAATTCTTAGTCAACCTCCTATCACCAGGCGCG | xcpYL for pUT18C |

| XcpZM-pUT18C-F | CCCGGATCCCATGAAGGTGATGACGCAATTCCACG | xcpZM for pUT18C |

| XcpZM-pUT18C-R | GGAATTCTTAGTCACTCGACCCGCAGGCTCAGG | xcpZM for pUT18C |

| XcpZM-pKT25-F | CCCGGATCCCATGAAGGTGATGACGCAATTCCACG | xcpZM for pKT25C |

| XcpZM-pKT25-R | GGAATTCTTAGTCACTCGACCCGCAGGCTCAGG | xcpZM for pKT25C |

| XcpSF-pKT25-F | CCCGGATCCCATGGCCGCCTTCGAATACCTCG | xcpSF for pKT25C |

| XcpSF-pKT25-R | GGAATTCTTAGTTACCCCACGAGTTGGTTGAGAG | xcpSF for pKT25C |

Protein production and purification

The DNA sequences encoding the periplasmic domains of XcpYL (XcpYLp; from residue 255 to residue 381) and XcpZM (XcpZMp; from residue 53 to residue 173) were cloned into pLIC07 vector using the SLIC method between BsaI sites. These constructs allow the production of XcpYLp and XcpZMp proteins fused to thioredoxin (Trx) at their N terminus. The Trx is cleaved off after purification, and the resulting proteins are soluble, stable, and produced in sufficient amount for biochemical and biophysical characterization. Competent cells of strain BL21 (DE3) were transformed with pLIC-XcpZMp or pLIC-XcpYLp. The bacteria were grown until reaching an A600 nm of 0.5 at 37 °C on TB medium with kanamycin at 50 μg/ml. Induction was performed with 0.1 mm IPTG for 12 h at 25 °C. Bacteria were collected by centrifugation and broken by sonication (4 × 1 min) in cold buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 300 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 20 mm MgCl2, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 mg/ml lysozyme, 20 μg/ml DNase, 10 mm imidazole). The lysate was cleared by ultracentrifugation (20,000 × g) to remove unbroken debris and membranes. The cleared lysates containing Trx-XcpYLp and Trx-XcpZMp were loaded onto a 5-ml nickel column (HisTrapTM FF) using an ÄKTA Prime apparatus (GE Healthcare), and the immobilized proteins were eluted in buffer B (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mm NaCl, 500 mm imidazole). XcpYLp and XcpZMp were obtained after cleavage of the Trx fusion using 2 mg of tobacco etch virus protease for 18 h at 4 °C and dialysis in a dialysis bag to remove imidazole. Untagged soluble proteins were then collected in the flow-through of a 5-ml nickel column; the histidine-tagged tobacco etch virus and Trx proteins remained bound to the column. The proteins were concentrated using Centricon technology (Millipore; 10-kDa cutoff) and subjected to size-exclusion chromatography purification using a HiLoad Superdex200 16/600 column pre-equilibrated with 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 150 mm NaCl.

For CbpD, the extraction and purification protocols of the periplasmic material were described previously (5). Purity and quality of the purified proteins were checked by analyzing samples by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining.

SDS-PAGE and immunodetection

Proteins from bacterial extracts were separated by electrophoresis on 15 or 18% polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes using a semidry blotting apparatus. Membranes were blocked with 5% milk in TBST (10 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) or in PBS. Membranes were incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against CbpD, XcpYL, XcpZM, and LapA (respectively diluted at 1:5000, 1:1500, 1:500, and 1:5000 in TBST, 5% milk). The incubation was followed by two 10-min washes and incubation in peroxidase-coupled anti-rabbit antibody (1:5000; Sigma). Membranes were developed by homemade enhanced chemiluminescence and scanned using ImageQuant TL analysis software (GE Healthcare).

Coproduction of XcpYp, XcpZp, LapAH, and CbpDH in E. coli and affinity chromatography

Competent cells of strain BL21 (DE3) were cotransformed with pCDFDuet, pETDuet, and derivatives. The bacteria were grown until reaching an A600 nm of 0.5 at 37 °C on LB or TB medium with appropriate antibiotics (30 μg/ml streptomycin, 50 μg/ml ampicillin). Induction was performed with 0.1 mm IPTG for 12 h at 17 or 25 °C. Bacteria were collected by centrifugation and broken using a French press (10,000 p.s.i.) in cold buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 20 mm MgCl2, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 mg/ml lysozyme, 20 μg/ml DNase). The lysate was cleared by ultracentrifugation to remove unbroken debris and membranes. The cleared lysate was loaded onto a 1-ml nickel column (HisTrap FF) using an ÄKTA Prime apparatus. The immobilized proteins were eluted in buffer B (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 150 mm NaCl, 500 mm imidazole). The loaded, flow-through, and elution fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunodetection. For competition experiments, the complete CbpD copurification IMAC procedure for XcpYL, XcpZM, and XcpYL together with XcpZM was performed in quadruplicate. The total amount of XcpYL or XcpZM proteins in the eluate fractions (in percent; compared with the total amount in the loaded fraction) was measured and quantified from immunoblots of each replicate using ImageJ software. Microsoft Excel software was used for data processing and presentation. Statistics were determined using the Student's t test function of Excel using a bilateral model and assuming equal variance.

Biolayer interferometry

CbpD was biotinylated using the EZ-Link NHS-PEG4-Biotin kit (Perbio Science, France) with a 1:1 molar ratio (CbpD:biotin). The reaction was stopped by removing excess biotin using a Zeba Spin desalting column (Perbio Science). BLI studies were performed in triplicate in black 96-well plates (Greiner) at 25 °C using an OctetRed96 (ForteBio). Streptavidin biosensor tips (ForteBio) were first hydrated with 0.2 ml of interaction buffer (IB) (1× Kinetics Buffer (ForteBio) diluted in PBS) for 20 min and then loaded with biotinylated protein (CbpD at 5 μg/ml in IB).

To study the binding of CbpD to XcpYLp or XcpZMp, increasing concentrations of XcpYLp (5–160 μm) and XcpZMp (6.25–100 μm) were used, and the association and dissociation phases were monitored for 1000 and 3000 s, respectively. Xcp proteins were dialyzed against IB before titration experiments. To avoid nonspecific binding of XcpYLp or XcpZMp to the streptavidin biosensors, the biosensors were incubated with 10 ug/ml biocytin (Sigma) for 200 s. In all experiments, the response of the nonbiotinylated proteins on the free sensors was subtracted during experiment processing.

The KD values were calculated using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software on the basis of the steady-state levels of the responses in nanometers, directly related to the concentration of the Xcp protein. The KD was calculated from a triplicate experiment by plotting on the x axis the different concentrations of the Xcp protein and the different responses of the Xcp protein at saturation (990 s after the start of the association step) on the y axis. Nonlinear regression fitting for xy analysis and a one-site binding (specific binding) model, corresponding to the equation y = Bmax × x/(KD + x), were used to calculate KD values.

Bacterial two-hybrid system and statistical analysis

To investigate the interaction between XcpZM and XcpYL periplasmic domains, competent cells of strain BTH101 were cotransformed with pUT18C and pKT25 derivatives, and bacteria were grown for 48 h at 30 °C on LB plates containing Ap100, Kan50, and Sm100. Colonies were picked at random; inoculated into 600-μl cultures in LB containing Amp100, Kan50, Sm100, and 0.5 mm IPTG; and grown overnight at 30 °C. β-Gal activity was measured as described (45). At least two independent experiments were performed with three randomly picked transformants. Mean values are presented as bar graphs, and error bars indicate S.D. Microsoft Excel software was used for data processing and presentation. Statistics were determined using the Student's t test function of Excel using a bilateral model and assuming equal variance.

To study the interaction network among the full-length proteins, competent cells of BTH101 containing pJN105 or pJN105-CbpD vectors were cotransformed with pUT18C and pKT25 derivates. Bacteria were grown for 48 h at 30 °C on LB plates containing Ap100, Kan50, Sm100, and Gm15. Colonies were picked at random and inoculated into 600-μl cultures in LB containing Ap100, Kan50, Sm100, Gm15, 0.5 mm IPTG, and 0.5% arabinose to allow CbpD production. Cells were grown overnight at 30 °C, and β-gal activity was measured as described (45).

Author contributions

S. M.-S., B. D., F. C., and R. V. conceptualization; S. M.-S., B. D., F. C., C. R., L. Q., G. B., and R. V. investigation; S. M.-S., B. D., F. C., L. Q., G. B., and R. V. methodology; S. M.-S., B. D., and R. V. writing-original draft; B. D. and R. V. writing-review and editing; R. V. resources; B. D. and R. V. data curation; R. V. supervision; R. V. funding acquisition; R. V. validation; R. V. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank V. Pelicic for careful reading of the manuscript; D. Byrne from the protein production platform of our institute (IMM) for BLI facility; N. O. Gomez and S. Bulot for help with statistical analysis; E. Bouveret for BACTH plasmids; and S. Rinaldi, O. Uderso, M. Ba, I. Bringer, and A. Brun for media and material preparation.

This work was supported by Agence Nationale de la Recherche Grant ANR-14-CE09-0027-01 (to R. V.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S3.

- Tff

- type IV filament

- T2SS

- type 2 secretion system

- AP

- assembly platform

- TM

- transmembrane

- IM

- inner membrane

- HR

- homology region

- BLI

- biolayer interferometry

- KD

- dissociation constant

- Sp

- signal peptide

- IMAC

- immobilized metal affinity chromatography

- BACTH

- bacterial adenylate cyclase two-hybrid

- PAS

- Per-Arnt-Sim

- SLIC

- sequence- and ligation-independent cloning

- MCS

- multiple cloning site

- Trx

- thioredoxin

- TB

- terrific broth

- IPTG

- isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside

- IB

- interaction buffer

- Ap100

- 100 μg/ml ampicillin

- Kan50

- 50 μg/ml kanamycin

- Sm100

- 100 μg/ml streptomycin

- Gm15

- 15 μg/ml gentamycin.

References

- 1. Berry J. L., and Pelicic V. (2015) Exceptionally widespread nanomachines composed of type IV pilins: the prokaryotic Swiss Army knives. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 39, 134–154 10.1093/femsre/fuu001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cianciotto N. P., and White R. C. (2017) Expanding role of type II secretion in bacterial pathogenesis and beyond. Infect. Immun. 85, e00014–17 10.1128/IAI.00014-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thomassin J. L., Santos Moreno J., Guilvout I., Tran Van Nhieu G., and Francetic O. (2017) The trans-envelope architecture and function of the type 2 secretion system: new insights raising new questions. Mol. Microbiol. 105, 211–226 10.1111/mmi.13704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gu S., Shevchik V. E., Shaw R., Pickersgill R. W., and Garnett J. A. (2017) The role of intrinsic disorder and dynamics in the assembly and function of the type II secretion system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1865, 1255–1266 10.1016/j.bbapap.2017.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Douzi B., Trinh N. T. T., Michel-Souzy S., Desmyter A., Ball G., Barbier P., Kosta A., Durand E., Forest K. T., Cambillau C., Roussel A., and Voulhoux R. (2017) Unraveling the self-assembly of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa XcpQ secretin periplasmic domain provides new molecular insights into T2SS secreton architecture and dynamics. mBio 8, e01185–17 10.1128/mBio.01185-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hay I. D., Belousoff M. J., and Lithgow T. (2017) Structural basis of type 2 secretion system engagement between the inner and outer bacterial membranes. mBio 8, e01344–17 10.1128/mBio.01344-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yan Z., Yin M., Xu D., Zhu Y., and Li X. (2017) Structural insights into the secretin translocation channel in the type II secretion system. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 24, 177–183 10.1038/nsmb.3350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Douzi B., Durand E., Bernard C., Alphonse S., Cambillau C., Filloux A., Tegoni M., and Voulhoux R. (2009) The XcpV/GspI pseudopilin has a central role in the assembly of a quaternary complex within the T2SS pseudopilus. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 34580–34589 10.1074/jbc.M109.042366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cisneros D. A., Bond P. J., Pugsley A. P., Campos M., and Francetic O. (2012) Minor pseudopilin self-assembly primes type II secretion pseudopilus elongation. EMBO J. 31, 1041–1053 10.1038/emboj.2011.454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nivaskumar M., Santos-Moreno J., Malosse C., Nadeau N., Chamot-Rooke J., Tran Van Nhieu G., and Francetic O. (2016) Pseudopilin residue E5 is essential for recruitment by the type 2 secretion system assembly platform. Mol. Microbiol. 101, 924–941 10.1111/mmi.13432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Santos-Moreno J., East A., Guilvout I., Nadeau N., Bond P. J., Tran Van Nhieu G., and Francetic O. (2017) Polar N-terminal residues conserved in type 2 secretion pseudopilins determine subunit targeting and membrane extraction steps during fibre assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 429, 1746–1765 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sandkvist M., Hough L. P., Bagdasarian M. M., and Bagdasarian M. (1999) Direct interaction of the EpsL and EpsM proteins of the general secretion apparatus in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 181, 3129–3135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Login F. H., and Shevchik V. E. (2006) The single transmembrane segment drives self-assembly of OutC and the formation of a functional type II secretion system in Erwinia chrysanthemi. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 33152–33162 10.1074/jbc.M606245200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lallemand M., Login F. H., Guschinskaya N., Pineau C., Effantin G., Robert X., and Shevchik V. E. (2013) Dynamic interplay between the periplasmic and transmembrane domains of GspL and GspM in the type II secretion system. PLoS One 8, e79562 10.1371/journal.pone.0079562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abendroth J., Rice A. E., McLuskey K., Bagdasarian M., and Hol W. G. (2004) The crystal structure of the periplasmic domain of the type II secretion system protein EpsM from Vibrio cholerae: the simplest version of the ferredoxin fold. J. Mol. Biol. 338, 585–596 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abendroth J., Kreger A. C., and Hol W. G. (2009) The dimer formed by the periplasmic domain of EpsL from the type 2 Secretion system of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Struct. Biol. 168, 313–322 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.07.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gérard-Vincent M., Robert V., Ball G., Bleves S., Michel G. P., Lazdunski A., and Filloux A. (2002) Identification of XcpP domains that confer functionality and specificity to the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type II secretion apparatus. Mol. Microbiol. 44, 1651–1665 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02991.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Korotkov K. V., Johnson T. L., Jobling M. G., Pruneda J., Pardon E., Héroux A., Turley S., Steyaert J., Holmes R. K., Sandkvist M., and Hol W. G. (2011) Structural and functional studies on the interaction of GspC and GspD in the type II secretion system. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002228 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang X., Pineau C., Gu S., Guschinskaya N., Pickersgill R. W., and Shevchik V. E. (2012) Cysteine scanning mutagenesis and disulfide mapping analysis of arrangement of GspC and GspD protomers within the type 2 secretion system. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 19082–19093 10.1074/jbc.M112.346338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abendroth J., Bagdasarian M., Sandkvist M., and Hol W. G. (2004) The structure of the cytoplasmic domain of EpsL, an inner membrane component of the type II secretion system of Vibrio cholerae: an unusual member of the actin-like ATPase superfamily. J. Mol. Biol. 344, 619–633 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abendroth J., Mitchell D. D., Korotkov K. V., Johnson T. L., Kreger A., Sandkvist M., and Hol W. G. (2009) The three-dimensional structure of the cytoplasmic domains of EpsF from the type 2 secretion system of Vibrio cholerae. J. Struct. Biol. 166, 303–315 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ball G., Chapon-Hervé V., Bleves S., Michel G., and Bally M. (1999) Assembly of XcpR in the cytoplasmic membrane is required for extracellular protein secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 181, 382–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen Y. L., and Hu N. T. (2013) Function-related positioning of the type II secretion ATPase of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. PLoS One 8, e59123 10.1371/journal.pone.0059123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pineau C., Guschinskaya N., Robert X., Gouet P., Ballut L., and Shevchik V. E. (2014) Substrate recognition by the bacterial type II secretion system: more than a simple interaction. Mol. Microbiol. 94, 126–140 10.1111/mmi.12744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lu C., Korotkov K. V., and Hol W. G. (2014) Crystal structure of the full-length ATPase GspE from the Vibrio vulnificus type II secretion system in complex with the cytoplasmic domain of GspL. J. Struct. Biol. 187, 223–235 10.1016/j.jsb.2014.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shiue S. J., Kao K. M., Leu W. M., Chen L. Y., Chan N. L., and Hu N. T. (2006) XpsE oligomerization triggered by ATP binding, not hydrolysis, leads to its association with XpsL. EMBO J. 25, 1426–1435 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Camberg J. L., Johnson T. L., Patrick M., Abendroth J., Hol W. G., and Sandkvist M. (2007) Synergistic stimulation of EpsE ATP hydrolysis by EpsL and acidic phospholipids. EMBO J. 26, 19–27 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Campos M., Cisneros D. A., Nivaskumar M., and Francetic O. (2013) The type II secretion system—a dynamic fiber assembly nanomachine. Res. Microbiol. 164, 545–555 10.1016/j.resmic.2013.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Leighton T. L., Yong D. H., Howell P. L., and Burrows L. L. (2016) Type IV pilus alignment subcomplex proteins PilN and PilO form homo- and heterodimers in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 19923–19938 10.1074/jbc.M116.738377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pugsley A. P., Kornacker M. G., and Poquet I. (1991) The general protein-export pathway is directly required for extracellular pullulanase secretion in Escherichia coli K12. Mol. Microbiol. 5, 343–352 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02115.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Voulhoux R., Ball G., Ize B., Vasil M. L., Lazdunski A., Wu L. F., and Filloux A. (2001) Involvement of the twin-arginine translocation system in protein secretion via the type II pathway. EMBO J. 20, 6735–6741 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Douzi B., Filloux A., and Voulhoux R. (2012) On the path to uncover the bacterial type II secretion system. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 367, 1059–1072 10.1098/rstb.2011.0204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shevchik V. E., Robert-Baudouy J., and Condemine G. (1997) Specific interaction between OutD, an Erwinia chrysanthemi outer membrane protein of the general secretory pathway, and secreted proteins. EMBO J. 16, 3007–3016 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Douzi B., Ball G., Cambillau C., Tegoni M., and Voulhoux R. (2011) Deciphering the Xcp Pseudomonas aeruginosa type II secretion machinery through multiple interactions with substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 40792–40801 10.1074/jbc.M111.294843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reichow S. L., Korotkov K. V., Gonen M., Sun J., Delarosa J. R., Hol W. G., and Gonen T. (2011) The binding of cholera toxin to the periplasmic vestibule of the type II secretion channel. Channels 5, 215–218 10.4161/chan.5.3.15268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Reichow S. L., Korotkov K. V., Hol W. G., and Gonen T. (2010) Structure of the cholera toxin secretion channel in its closed state. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 1226–1232 10.1038/nsmb.1910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bouley J., Condemine G., and Shevchik V. E. (2001) The PDZ domain of OutC and the N-terminal region of OutD determine the secretion specificity of the type II out pathway of Erwinia chrysanthemi. J. Mol. Biol. 308, 205–219 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ball G., Durand E., Lazdunski A., and Filloux A. (2002) A novel type II secretion system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 475–485 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02759.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Karimova G., Pidoux J., Ullmann A., and Ladant D. (1998) A bacterial two-hybrid system based on a reconstituted signal transduction pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 5752–5756 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Georgiadou M., Castagnini M., Karimova G., Ladant D., and Pelicic V. (2012) Large-scale study of the interactions between proteins involved in type IV pilus biology in Neisseria meningitidis: characterization of a subcomplex involved in pilus assembly. Mol. Microbiol. 84, 857–873 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08062.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sandkvist M. (2001) Biology of type II secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 40, 271–283 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02403.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nivaskumar M., Bouvier G., Campos M., Nadeau N., Yu X., Egelman E. H., Nilges M., and Francetic O. (2014) Distinct docking and stabilization steps of the pseudopilus conformational transition path suggest rotational assembly of type IV pilus-like fibers. Structure 22, 685–696 10.1016/j.str.2014.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gray M. D., Bagdasarian M., Hol W. G., and Sandkvist M. (2011) In vivo cross-linking of EpsG to EpsL suggests a role for EpsL as an ATPase-pseudopilin coupling protein in the type II secretion system of Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 79, 786–798 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07487.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Henry J. T., and Crosson S. (2011) Ligand-binding PAS domains in a genomic, cellular, and structural context. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65, 261–286 10.1146/annurev-micro-121809-151631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Miller J. H. (1972) Experiments in Molecular Genetics, pp 156–158, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 46. Douzi B., Brunet Y. R., Spinelli S., Lensi V., Legrand P., Blangy S., Kumar A., Journet L., Cascales E., and Cambillau C. (2016) Structure and specificity of the Type VI secretion system ClpV-TssC interaction in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 6, 34405 10.1038/srep34405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cadoret F., Ball G., Douzi B., and Voulhoux R. (2014) Txc, a new type II secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA7, is regulated by the TtsS/TtsR two-component system and directs specific secretion of the CbpE chitin-binding protein. J. Bacteriol. 196, 2376–2386 10.1128/JB.01563-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Newman J. R., and Fuqua C. (1999) Broad-host-range expression vectors that carry the L-arabinose inducible Escherichia coli araBAD promoter and the araC regulator. Gene 227, 197–203 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00601-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.