Abstract

Sterol 14α-demethylases (CYP51s) are phylogenetically the most conserved cytochromes P450, and their three-step reaction is crucial for biosynthesis of sterols and serves as a leading target for clinical and agricultural antifungal agents. The structures of several (bacterial, protozoan, fungal, and human) CYP51 orthologs, in both the ligand-free and inhibitor-bound forms, have been determined and have revealed striking similarity at the secondary and tertiary structural levels, despite having low sequence identity. Moreover, in contrast to many of the substrate-promiscuous, drug-metabolizing P450s, CYP51 structures do not display substantial rearrangements in their backbones upon binding of various inhibitory ligands, essentially representing a snapshot of the ligand-free sterol 14α-demethylase. Here, using the obtusifoliol-bound I105F variant of Trypanosoma cruzi CYP51, we report that formation of the catalytically competent complex with the physiological substrate triggers a large-scale conformational switch, dramatically reshaping the enzyme active site (3.5–6.0 Å movements in the FG arm, HI arm, and helix C) in the direction of catalysis. Notably, our X-ray structural analyses revealed that the substrate channel closes, the proton delivery route opens, and the topology and electrostatic potential of the proximal surface reorganize to favor interaction with the electron-donating flavoprotein partner, NADPH–cytochrome P450 reductase. Site-directed mutagenesis of the amino acid residues involved in these events revealed a key role of active-site salt bridges in contributing to the structural dynamics that accompanies CYP51 function. Comparative analysis of apo-CYP51 and its sterol-bound complex provided key conceptual insights into the molecular mechanisms of CYP51 catalysis, functional conservation, lineage-specific substrate complementarity, and druggability differences.

Keywords: cytochrome P450, conformational change, catalysis, X-ray crystallography, structure-function, drug target, druggability, sterol 14alpha-demethylase (CYP51), sterol biosynthesis, substrate binding

Introduction

Cytochrome P450 (CYP or P450)2 enzymes perform multiple biological functions, ranging from degradation of xenobiotics (e.g. drugs and pollutants) to the synthesis of vital endogenous compounds (e.g. steroids, vitamins, fatty acids). While drug-metabolizing CYPs are known for their broad substrate promiscuity, the P450s involved in physiological processes display more strict specificity toward their natural substrates. Sterol 14α-demethylases (CYP51) belong to this second group of P450s, the major distinguishing features of the family being the broadest distribution in nature (found in all biological domains) and the profound functional conservation (the same three-step stereospecific reaction across phylogeny) (1). From bacteria to humans, CYP51s catalyze the removal of the 14α-methyl group from the core of one or more of the five naturally occurring cyclized sterol precursors, i.e. lanosterol, 24,25-dihydrolanosterol, eburicol, obtusifoliol, or norlanosterol (Fig. S1A).

The CYP51 reaction includes three consecutive monooxygenation steps (Fig. S1B), in other words three cytochrome P450 catalytic cycles (2), except that the resting (water-bound) low-spin ferric state of the heme iron between cycles 1 and 3 is missing because of the presence of the substrate in the enzyme active center (3). When the substrate binds, it displaces the water molecule from the sixth (distal axial) position in the coordination sphere of the ferric heme iron. The pentacoordinated Fe3+ atom becomes high-spin, and its reduction potential increases. The P450 interacts with its redox partner protein (NADPH–cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR), in the case of eukaryotic CYP51s) and accepts one electron forming a high-spin ferrous complex (Fe2+). Subsequent binding of molecular oxygen yields the ferrous dioxygen complex (Fe2+–O–O), which triggers acceptance of a second electron from CPR, producing the ferric-peroxo anion (Fe3+–O–O2−). The ferric-peroxo complex is then protonated to form the ferric-hydroperoxo intermediate (Fe3+–O–OH−), the second protonation of whose distal oxygen atom causes heterolytic scission of the O–O bond, release of water, and generation of a highly reactive Fe4+–oxo cation radical (formally FeO3+, compound I (4)), which oxygenates the sterol 14α-methyl group forming the 14α-hydroxymethyl derivative. The iron returns into the ferric state yet remains pentacoordinated high-spin, ready to accept another electron from CPR and proceed to the second monooxygenation cycle. The second cycle produces the 14α-formyl derivative, and the third cycle removes it as formic acid, with the concomitant introduction of the Δ14–15 double bond into the sterol core (1). Thus, altogether, the CYP51 reaction consumes six electrons, three molecules of oxygen, and six protons.

The CYP51 reaction is required for biosynthesis of sterols that are indispensable components of eukaryotic membranes and also serve as precursors for many kinds of crucial regulatory molecules, such as steroid hormones, nuclear receptors, etc. As a result, CYP51 is the leading target for clinical and agricultural antifungals, is in trials as a target for protozoan infections (5), and is being investigated as a potential target for cholesterol-lowering drugs and post-cancer chemotherapy (6). The role of CYP51 in most of the bacteria remains unclear, yet its presence in both proteobacteria and actinobacteria (5) implies a very ancient origin, supporting the suggestion that CYP51 could have been an evolutionary ancestor for all currently existing cytochromes P450 (7, 8). Thus, further understanding of the CYP51 structure/function can be applied not only for the design of new more efficient CYP51-targeting drugs but should also advance the general knowledge on the P450 molecular mechanisms and information about P450 evolution.

To date crystal structures of CYP51s from different phyla have been determined, in the ligand-free state (9) and in complex with various inhibitors. Overall, the structures display a striking similarity across phyla (10, 11) and do not reveal any substantial rearrangements in the protein backbone upon binding of inhibitors, either heterocycle-based (azoles (9, 11–13), pyridines (14)), or the substrate analog 14α-methylenecyclopropyl-Δ7-24,25-dihydrolanosterol (MCP) (3) (Fig. S2). This lack of structural change led us to the hypothesis that the remarkable druggability of some pathogenic CYP51 (there are azoles that completely block their activity for extended periods of time when added at an equimolar ratio to the enzyme (5, 15)) must be somehow connected with high structural rigidity of the CYP51 active site (10).

The lack of conformational changes in response to inhibitor binding in the CYP51 crystal structures is in a good agreement with our previous FRET-based data (in the solution) that detected no conformational changes in the CYP51 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis upon binding of ketoconazole, fluconazole, or the substrate analog estriol (16). The same experiments, however, demonstrated up to 10 Å movement in the enzyme FG arm (F″ helix) in response to the binding of the substrate lanosterol, thus strongly suggesting that large-scale conformational dynamics must still be involved in CYP51 catalysis, and the evidence for this is provided for the first time in this study.

Results and discussion

Crystallization and structure determination

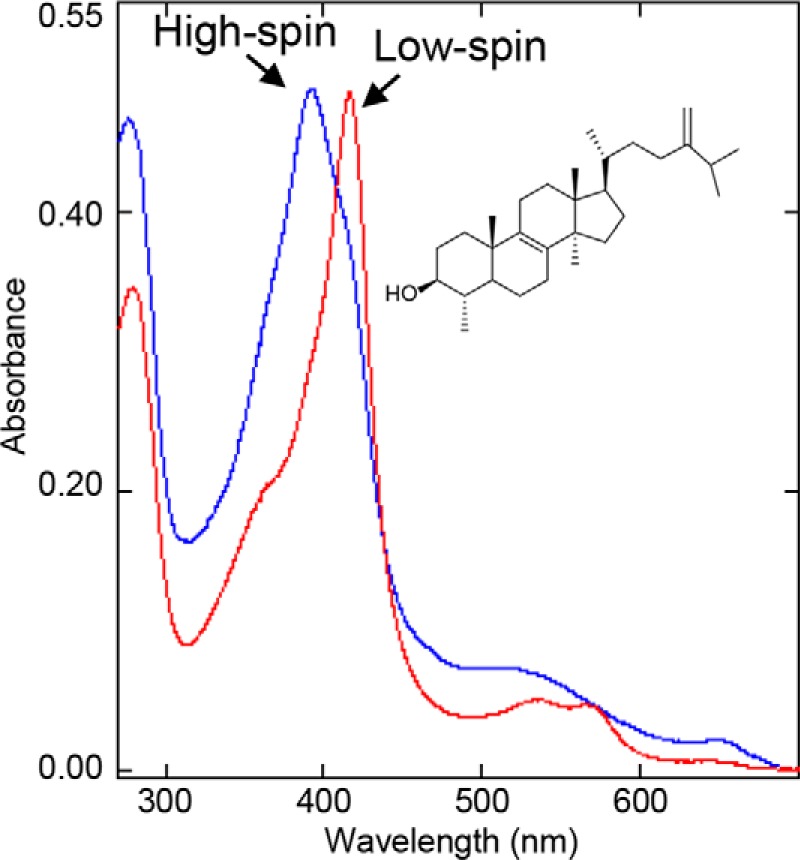

For many years our attempts to co-crystallize CYP51 in complex with a natural substrate were unsuccessful. First, the CYP51 substrates are highly hydrophobic (Fig. S1A) and therefore have poor solubility in water (e.g. obtusifoliol, lanosterol, and eburicol have estimated (ChemDraw Professional) n-octanol/water partition coefficients (log P) values of 8.0, 8.2, and 8.6, respectively). Second, in vitro most CYP51 orthologs do not produce more than 20–40% spectral transition into the high-spin form upon substrate binding (9). Moreover, in our experience, CYP51s from Trypanosoma brucei, Aspergillus fumigatus, and humans lost their substrates upon crystallization, with their heme iron returning to the low-spin water-bound state. Several high-resolution datasets were collected, but no clear density for a sterol molecule was observed (14). The I105F mutant of Trypanosoma cruzi CYP51 was selected for this work (this mutation alters the enzyme substrate preferences, converting it from a fungi-like eburicol-specific CYP51 to the plant-like obtusifoliol-specific enzyme (17)), because we believed that it would retain the substrate upon crystallization: 1) the extent of its low-to-high spin transition in response to the binding of obtusifoliol was >85% (Fig. 1), 2) the protein from the dissolved crystals remained predominantly high-spin, and 3) the density for obtusifoliol was clearly seen even at a very low (3.7 Å) resolution (Fig. S3).

Figure 1.

Spectral changes induced in the I105F mutant of T. cruzi CYP51 by obtusifoliol. Red, low-spin water-bound ferric P450; Soret band maximum, 417 nm. Blue, >85% high-spin substrate bound ferric P450; Soret band maximum, 393 nm. The increase in the absorbance at 280 nm is due to HPCD, which was used to dissolve the sterol.

The best resolution achievable was 3.18 Å, with R and Rfree values of 0.26 and 0.28, respectively, and the trigonal P3112 space group (Table 1). The asymmetric unit contained four CYP51 molecules; three of them were obtusifoliol-bound and one was ligand-free (Fig. 2A). Although the electron density of the ligand-free molecule coincided quite well with the Cα trace of the search model (RMSD, 0.8 Å), in the three obtusifoliol-bound molecules the density for several protein backbone segments (the FG arm, the HI arm, and helix C) clearly required manual model rebuilding (Fig. S4).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Complex | T. cruzi I105F CYP51-Obtusifoliol |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.12713 |

| Detector used | EIGER X 9 m |

| Exposure time | 0.4 s |

| Space group | P 31 1 2 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 154.31, 154.31, 178.876 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.00, 90.00, 120.00 |

| Molecules per asymmetric unit | 4 |

| Number of reflections | 38,484 |

| Resolution (outer shell) (Å) | 133.64–3.18 (3.27–3.18) |

| Rmerge (outer shell) | 0.061 (1.357) |

| I/σ (outer shell) | 14.6 (1.0) |

| Completeness (outer shell) (%) | 99.3 (99.6) |

| Redundancy (outer shell) | 6.2 (6.4) |

| Refinement | |

| Rwork | 0.260 |

| Rfree | 0.282 |

| RMSDs from ideal geometry | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.0016 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.846 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Residues in favorable/allowed regions (%) | 97/100 |

| Outliers (%) | 0 |

| Number of atoms (mean B-factor,Å2) | 14,610 (156.44) |

| Number of residues per molecule | A/B/C/D |

| Protein (mean B-factor, Å2) | 447 (137.8)/447 (161.4)/447 (170.2)/447 (166.9) |

| Heme (mean B-factor, Å2) | 1 (91.0)/1 (94.9)/1 (118.0) /1 (113) |

| Substrate (mean B-factor, Å2) | 1 (100.5)/1 (123.3)/1 (136.8) /0 (—) |

| PDB code | 6FMO |

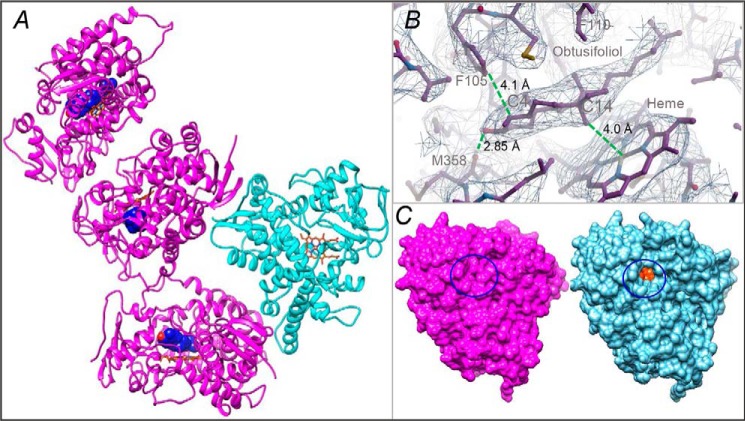

Figure 2.

X-ray structure of CYP51 in the substrate-bound (magenta) and ligand-free (cyan) state. A, the asymmetric unit. The carbon atoms of the substrate (obtusifoliol) molecule are seen as blue spheres, and the C3 OH oxygen is red. The heme is shown as a stick model, and the carbon atoms are orange. B, the 2Fo − Fc electron density map of the obtusifoliol area is shown as a mesh contoured at 1.2 σ, prepared in Coot. The distances between the C14α-methyl group and the heme iron, the C3-OH and the carbonyl oxygen of Met-358, and the C4 atom and Phe-105 are marked with dashed green lines. C, surface representation of the substrate-bound and ligand-free molecules, distal P450 view. The substrate entry area (closed in the substrate-bound and open in the ligand-free structure) is circled. The heme is seen as orange spheres (see also Fig. S2C).

Obtusifoliol in the CYP51 active site

The position of the obtusifoliol molecules is well-defined (Fig. 2B). The C3-OH group of the sterol nucleus interacts with the carbonyl oxygen of Met-358 (2.85 Å, β1–4), and the C14α-methyl group is located 4.0 Å from the heme iron, i.e. clearly in a catalytically competent orientation. The (α-monomethylated) C4 atom lies 4.1 Å below the phyla-specific residue Phe-105 (B′ helix), leaving no space for the second methyl group on the β-face of the sterol molecule. The aliphatic arm of obtusifoliol protrudes deep into the CYP51-specific portion of the binding cavity (18) formed by the B′C-loop and helices C and I. The orientation is overall similar (although not identical) to the orientation of MCP in T. brucei CYP51 (PDB code 3P99) (3) (Fig. S5) and, as we expected, opposite to the orientation proposed for lanosterol by Monk et al. (19), which can be because the electron density for lanosterol in their structure was very weak. Thus, when bound in a productive mode, the substrate enters the CYP51 active site with its aliphatic side chain first.

Substrate-induced rearrangements in the CYP51 structure

Overall, binding of the physiological substrate obtusifoliol causes a large-scale conformational switch in the CYP51 molecule that involves most of the structural segments of the active cite (Movie S1 and Fig. S6). Only the B′ helix and the β1–4 strand remain stable. The RMSD for the Cα atoms between the substrate-free and substrate-bound molecules is 2.0 Å, more than twice as high as the deviations observed upon binding of inhibitors (usually within 0.5–0.8 Å, e.g. 0.75 Å upon binding of MCP (3)).

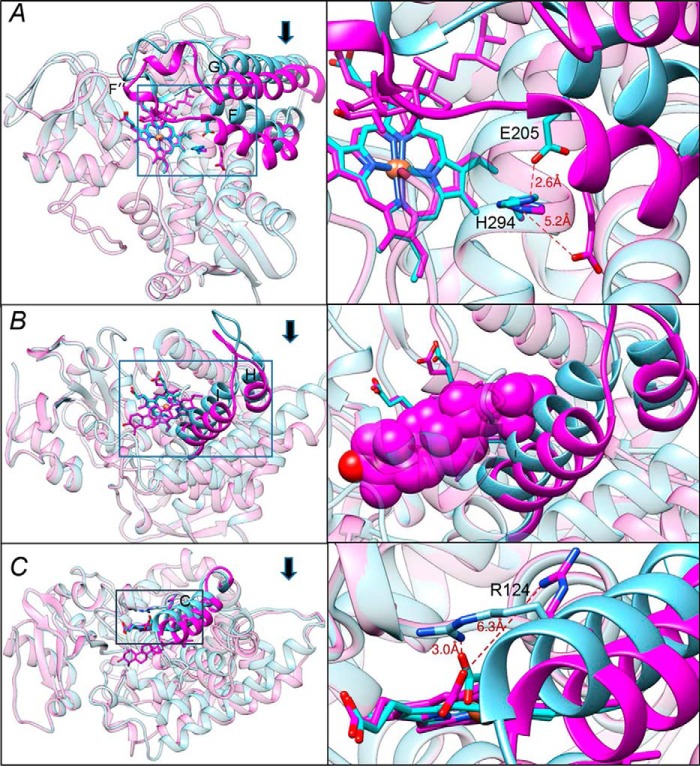

The FG arm (residues 185–250) moves 4–6 Å down, so that the F″ helix closes the entrance into the substrate access channel (Fig. 2C). This entrance is open in the ligand-free and in all inhibitor-bound CYP51 structures (11) (Fig. S2). Importantly, as a result of the FG-arm movement, the histidine-acid salt bridge conserved throughout the whole CYP51 family (11) (His-294 to Glu-205 in T. cruzi CYP51) that we and others believed to be involved in the CYP51 proton relay machinery (1, 10, 20) opens (Fig. 3A), presumably enabling the flow of protons from solvent to the iron-bound dioxygen.

Figure 3.

Conformational switch in the CYP51 structure upon binding of the substrate. The three segments of the active site that experience large-scale conformational rearrangements are shown in cyan (ligand-free structure) and magenta (substrate-bound structure). Arrows show the direction of movement. The other portions of the molecules are presented as semitransparent ribbons of the corresponding colors. Left panels, the overall view of the superimposed structures (see also Fig. S6); right panels, the enlarged view of the squared fragments. The structures were superimposed in LSQKAB (CCP4 Suite). A, the FG arm and the conserved histidine-acid salt-bridge opening (activation of proton relay machinery). B, the HI segment. In the enlarged fragment, obtusifoliol is presented as van der Waals spheres to show that without the movement it would collide with the (cyan) I helix. C, helix C. The 3.5–4 Å movement of this helix reshapes the CYP51 proximal surface. The inset shows rearrangements in the position of Arg-124, whose guanidino group now protrudes above the CYP51 proximal surface, bringing additional positive charge to its electrostatic potential (shown in Fig. 5).

The HI segment (residues 261–293) moves ∼4 Å toward the distal surface of the CYP51 molecule, somewhat following the movement of the C-terminal portion of helix G and thus creating additional volume for the aliphatic side chain of obtusifoliol that would otherwise collide with the upper portion of the I helix (Fig. 3B). The active site volume, however, remains essentially unchanged, or even slightly decreases, from 1,330 Å3 to 1,240 Å3, because of the rearrangements in helix C (calculated in Accelrys Discovery Studio; probe radius, 1.4 Å).

The C-helix (residues 119–138) moves ∼3.5–4 Å inside the protein globule approaching the substrate. It crosses the heme plane and shields the obtusifoliol side chain at the top (Fig. 3C). This large-scale movement alters the topology of the CYP51 proximal surface, the P450 area known to interact with the electron donor partner. Moreover, the guanidino group of Arg-124, which in the ligand-free and in most of the inhibitor-bound protozoan CYP51 structures forms the salt bridge with the heme ring D propionate, moves away from the propionate OH group and now protrudes above the proximal surface of the CYP51 molecule (Fig. 3C, right panel), suggesting that Arg-124 might be directly involved in the electron transfer.

The histidine-acid salt bridge is critical for proton delivery

The His residue in the middle of the I helix that is followed by the “conserved P450 threonine” (Fig. 4, A and B) is a signature residue in the CYP51 family, whereas in other P450s there is always an acidic residue (Glu or Asp) here (1). The corresponding Asp (Asp-251) in P450cam (CYP101A1) has been found to play a key role in proton transfer (21). Moreover, in the P450cam structure it is usually salt-bridged with the positively charged residues from the F-helix (Lys-178 and Arg-186). The bridges break, however, upon binding of the ferredoxin redox partner (putidaredoxin). The authors proposed that Asp-251 “has to be freed of salt bridges in order to serve its function in the proton relay network” (22). To test whether the conserved (although reverse-charged) His-acid salt bridge (Fig. 4, A and B) that opens upon binding of the substrate in our structure (Fig. 3A) plays a similar role in proton transfer in the CYP51 family, we mutated His-314 and Asp-231 (Fig. 4B) in human CYP51 to Ala and also made the double mutant (H314A/D231A). The human ortholog was selected for mutagenesis because, in our collection of CYP51 enzymes, catalytically it is the fastest (6), and therefore we expected the differences, if observed, to be most pronounced.

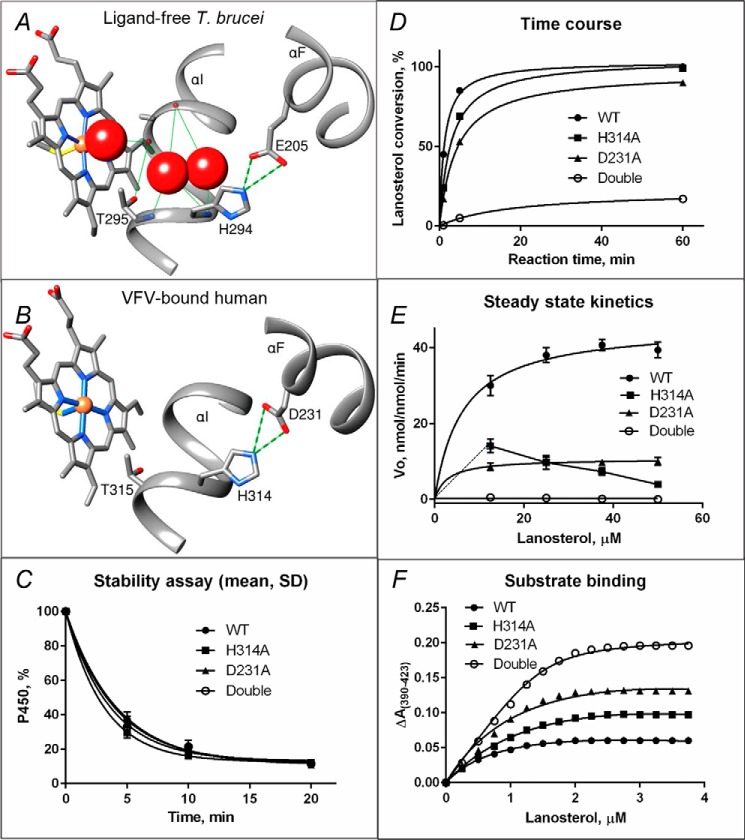

Figure 4.

Proposed proton delivery route in the CYP51 family. A, ligand-free water-coordinated protozoan CYP51 (PDB code 3G1Q, 1.8 Å resolution). The water molecules are presented as red spheres. B, inhibitor-bound human CYP51 (PDB code 4UHI, 2.0 Å resolution). C–F, mutants of the His-acid salt bridge in human CYP51. C, stability at 42 °C monitored as the decrease in the P450 content, the initial P450 concentration was 2 μm (see also Fig. S7). D, time course of substrate conversion, 0.5 μm P450, 25 μm lanosterol. E, Michaelis–Menten plots using 0.25 μm P450, 1 min reaction; points are shown as means of three determinations ± S.D. F, spectral response to lanosterol; 2 μm P450 (fit to Morrison equation, nonlinear regression). The estimated low-to-high spin transition was 30, 50, 68, and 94% in the WT, H314A, D231A, and the H314A/D231A double mutant proteins, respectively (see also Table 2).

The proteins were all expressed and purified (in the P450 form, i.e. not cytochrome P420) and did not display any substantial alterations in their stability (Fig. 4C and Fig. S7). Moreover, all of them were able to catalyze 14α-demethylation of lanosterol (Fig. 4D), so that over time (1 h) almost all of the substrate was converted into the product, both by the D231A protein (90%) and even more so by the H314A mutant (99%). The double mutant, however, was able to 14α-demethylate only 17% of the substrate. In these experiments, the most pronounced changes were seen in the initial rates of reaction: Within 1 min the WT converted 45% of the substrate, but the substrate conversion by H314A and D231A was 24 and 17%, respectively, and the double mutant 14α-demethylated converted only 0.5% of lanosterol. The data suggest that in CYP51 each of these two salt-bridged residues can support shuttling protons from solvent to dioxygen, to a certain degree compensating for each other, but in the absence of both of the residues only a trace (∼ 1%) of the catalytic activity remains.

The differences in the enzymatic activity of the mutants were much more apparent in steady-state kinetic experiments (Fig. 4E). While for D231A, both the kcat and Km values simply decreased, from 46 to 11 min−1 and from 6.2 to 2.9 μm, respectively, the turnover rate of the H314A mutant clearly dropped at the higher substrate concentrations (14.1, 9.7, 7.3, and 3.9 min−1 at 12.5, 25, 37.5, and 50 μm lanosterol, respectively), and the double mutant revealed a more than 2 orders of magnitude decrease in kcat (0.25 min−1), with a Km being unmeasurable because of the substrate-dependent drop in the reaction velocity (0.53, 0.37, and 0.14 min−1 and below detection limit at 12.5, 25, 37.5, and 50 μm of lanosterol).

Interestingly, the mutations did not affect the substrate binding affinity very much, with the calculated Kd values of 0.55, 0.73, 0.68, and 0.91 μm for the WT, H314A, D231A, and H314A/D231A proteins, respectively. Instead, they caused a notable increase in the amplitude of the spectral response to the substrate, especially in the H314A/D231A double mutant (94% low-to-high spin transition versus 30% in the WT) (Fig. 4F and Table 2). The observation that proton relay disruption results in a greater high-spin form content upon substrate addition might indicate that when both of the salt bridge–forming charges (the I-helix His and the F-helix acid) are missing, the protons (or water molecules) can flow both ways, making water displacement from the iron coordination sphere easier for the substrate or even merely causing loss of the active site water (“leaky water channel”). Attempts to co-crystallize the high-spin double mutant in the presence of lanosterol are currently in progress, and determination of the X-ray structure should address the question of whether the high-spin mutant is indeed substrate-bound or acquires the ability to exist in the high-spin (water-free) form even without the substrate. This feature (an equilibrium of low- and high-spin species in the absence of substrate) is known to exist for many P450s (23–26) but has never been observed for a CYP51 enzyme.

Table 2.

Substrate-binding parameters calculated from the spectral response of human CYP51 to the binding of lanosterol

| Human CYP51 | Low-to-high spin transition | Kd |

|---|---|---|

| % | μm | |

| WT | 30 | 0.55 |

| H314A | 68 | 0.73 |

| D231A | 50 | 0.68 |

| Double | 94 | 0.91 |

The heme-binding arginine is involved in the electron transfer mechanism

Comparison of the ligand-free and obtusifoliol-bound structures clearly shows that binding of the substrate not only alters the topology but also increases the positive charge on the proximal surface of the CYP51 molecule (Fig. 5A), apparently “preparing” it for the interaction with CPR. Although it is generally accepted that the interaction of P450 enzymes with their redox partners (27) occurs on the proximal (to the heme iron) P450 surface and is mainly electrostatic, the exact mode of binding or electron transfer mechanism remains elusive. To date, structures of three different P450/redox partner complexes have been determined, and four different hypotheses on the electron delivery pathways have been proposed. Two of them suggest that the electron transfer route (in bacterial P450-BM3 (CYP102) and in mitochondrial P450scc (CYP11A)) must be via the heme coordinating cysteine and involve a through-space jump (28, 29). The third (in P450cam) proposes participation of the porphyrin macrocycle and an Arg residue (Arg-112) from helix C (22). Finally, the data obtained using a combination of paramagnetic NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography (P450cam/putidaredoxin) suggest that coupling of both pathways is possible (30). Because (unlike CYP51) mitochondrial and most bacterial P450s use a small (10–15 kDa) protein (ferredoxin or flavodoxin) that shuttles between its own reductase and P450 for each electron delivery (27), it appears that in CYP51 the interaction with a 78-kDa CPR should be somewhat different, at least stronger, because six electrons must be transferred, one at a time, to the P450 molecule before the complex dissociates. Nevertheless, repositioning of Arg-124 upon substrate binding in our structure supports the “P450cam-like” route for the electron transfer in CYP51 (i.e. a negatively charged residue on the surface of the FMN-binding domain of CPR to the guanidino group of Arg-124 to the hydroxyl of the ring D propionate to the iron).

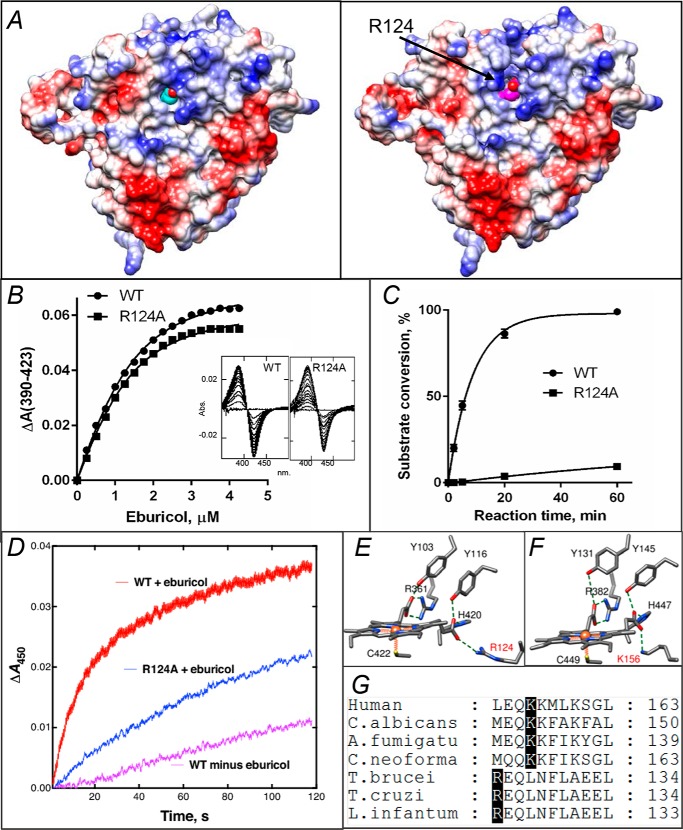

Figure 5.

In protozoan CYP51, Arg-124 must be involved into the electron transfer. A, proximal surface of the ligand-free (left panel) and substrate-bound (right panel) I105F T. cruzi CYP51 molecules colored by electrostatic potential (red for negative and blue for positive charge). The heme is seen in cyan and magenta, respectively. In the substrate-bound structure repositioning of helix C and exposure of the guanidino group of Arg-124 (marked with an arrow) adds positive charge to the surface, whereas in the substrate-free structure the guanidino group of Arg- 124 forms the H-bond with the heme ring D propionate. B, spectral response of the R124A mutant to the substrate binding, 2 μm P450; Kd = 0.6 μm; the high-spin form content 36% (fit to Morrison equation nonlinear regression). The response of the WT protein (Kd 0.5 μm, 39% high-spin) is shown as a comparison. C, time course of substrate conversion by T. cruzi CYP51, WT, and the R124A mutant. The reaction mixture contained 1 μm P450, 2 μm T. brucei CPR, and 50 μm eburicol. D, enzymatic reduction. Rates of reduction of (ferric) T. cruzi WT and R124A were measured under anaerobic conditions in the presence of CO at 23 °C, using final concentrations of 1 μm P450, 2 μm CPR, 150 μm DLPC, and 5 μm eburicol and estimated by global fitting of the 380–520-nm data points (from >4 individual reductions, ± S.D.) to first-order plots in the OLIS software: WT enzyme, 1.56 ± 0.24 min−1; WT minus substrate, 0.20 ± 0.02 min−1; R124A enzyme (with substrate), 0.65 ± 0.02 min−1. E, heme support in protozoan CYP51, ligand-free T. brucei, PDB code 3G1Q. F, heme support in VFV-bound human CYP51, PDB code 4UHI. Arg-124 and Lys-156 are labeled in red. G, fragment of CYP51 sequence alignment showing the Arg and Lys residues that form the salt bridge with the heme.

To verify functional importance of Arg-124, we made the R124A mutant of T. cruzi CYP51. Although expressed at a lower level (10–20 nmol/liter, possibly because of the folding problems caused by the weakened heme support), the mutant was in the P450 form and could be purified. Like the WT protein (17), it was easily reduced by sodium dithionite, forming a CO complex with a Soret band maximum at 448 nm and produced typical spectral response to the binding of the substrate (Fig. 5B). The enzymatic activity of R124A, however, was drastically affected, with no product formed after 2 min and more than a 100-fold lower turnover rate detected in a 5-min reaction (0.4% instead of 45% of the substrate conversion) (Fig. 5C). The corresponding steady-state kinetic values were kcat 2.4 versus 0.02 min−1 and Km 3.4 versus 0.3 μm for the WT and R124A, respectively (Fig. S8).

To test whether the alterations in the activity are related to the mutant enzyme ability to be reduced by the reductase, we used stopped-flow spectrophotometry (Fig. 5D); the results support the involvement of Arg-124 into the electron transfer process and also show the importance of the substrate (substrate-induced conformational dynamics) in the P450–CPR interaction. Interestingly, Arg-124 (the salt bridge with the hydroxyl of the porphyrin ring D propionate (Fig. 5E)) is conserved across protozoan CYP51 enzymes, but in animal/fungal orthologs this salt bridge is formed by a lysine residue (Lys-156 in human CYP51 (Fig. 5F)) that is positioned one turn downstream in helix C (Fig. 5G). Assuming that Lys-156 in human CYP51 plays the same role as Arg-124 in the CYP51s from protozoan pathogens, a new type of protozoan CYP51 inhibitors can potentially be designed that would target the specific portion of their electron channel (upper part of Fig. 5A).

To summarize, X-ray crystallography captured conformational dynamics related to binding of the physiological substrate, providing new conceptual insights into molecular mechanisms of CYP51 catalysis and functional conservation. Four structural segments that form the CYP51 substrate binding cavity (18) come into play. Closing the substrate entrance (helix F″ and the tip of the β4-hairpin (seen in Fig. S6)), enabling electron delivery by optimizing the surface of interaction with CPR (helix C plus the flip of the Arg-124 side chain), and activation of the proton relay machinery (the FG-arm repositioning and the His-acid salt-bridge opening, required for the O–O bond heterolysis) all accompany accommodation of the substrate in the catalytically competent position. It seems possible that all this huge rearrangement is the concerted preparation of the CYP51 catalytic machinery for the three following consecutive reaction cycles, the process that (unlike in the vast majority of other cytochrome P450 enzymes) occurs without the substrate release after its (first and second) monooxygenation reactions (18). Gradual “weakening” of these requirements over time, simplifying the enzyme catalysis, could have resulted in functional diversification and initiate P450 evolution. There are, of course, still many questions to be answered.

Closing of the substrate entrance

It is quite generally accepted that in most P450s the FG arm serves as the gate, opening the entrance into the P450 active site, both for the substrates and for the iron-coordinating inhibitors. Does it close upon (productive) substrate binding in all P450s? For example, it is indeed closed in cholesterol-bound CYP46A1, PDB code 2Q9F (31); cholesterol- and 22R-hydroxycholesterol-bound CYP11A1 (PDB codes 3N9Y (29) and 3MZS (32), respectively); or midazolam-bound CYP3A4, PDB code 5TE8 (33). It cannot be excluded that this structural “snapshot” is just not always captured by X-ray crystallography perhaps because its lifetime is shorter in the P450s that catalyze a single monooxygenation or have a distributive catalytic mechanism or perhaps because the substrates in some crystal structures are not bound in a productive mode.

Proton relay machinery

Why is the charge of the salt bridge pair “reversed” in the CYP51 family, or rather why has it been switched upon P450 diversification? The P450s that are located downstream from CYP51 in the sterol biosynthesis pathway/steroidogenesis (and thus might be evolutionarily closest to CYP51), e.g. CYP61 (sterol C22-desaturase, EC 1.14.19.41) and CYP11A (cholesterol monooxygenase (side chain–cleaving), EC 1.14.15.6) have an Asp residue instead of His here. Is His more potent as a “proton pump,” perhaps because of its nitrogen atom, with a charge opposite to the hydroxyl of the side chain of the “conserved P450 threonine”? Does it diminish the Thr role in CYP51 catalysis (in many CYP51 enzymes there is a Ser residue instead of Thr in this position (1))? What would happen if the His-acid pair is mutated back? Would such a mutant still function as a sterol 14α-demethylase, or would it acquire new catalytic functions?

Electron transfer

Why do different P450s appear to use different electron transfer routes? Does it depend on the nature of the electron donor partner, the cellular localization, or the physiological role? The involvement of the protozoan Arg-124 in the electron transfer that we report in this work is similar to the role suggested for Arg-112 in P450cam (22). Does it somewhat support a bacterial origin of CYP51, or is this just a coincidence?

Enzyme inhibition

Finally, the large-scale conformational switch in the CYP51 molecule that accompanies the enzyme–substrate complex formation provides an explanation as to why some CYP51 inhibitors can act as functionally irreversible with zero partition ratio. Most likely, strong interactions with the protein upon their binding (e.g. H-bonds within the active site or multiple van der Waals contacts around the substrate entrance (Fig. S9)) impede the CYP51 dynamics, preventing the conformational switch from happening by “freezing” the enzyme in its catalytically incompetent (ligand-free–like) state.

Experimental procedures

Protein purification, crystallization, and structure determination

The full-length WT and mutant proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as previously described (6, 17). For crystallization purposes, the 31 N-terminal amino acids of I105F T. cruzi CYP51 were replaced with MAKKT- (12). The molecular weight and purity of the protein was confirmed by SDS-PAGE. The correctness of the genes was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

The crystals were obtained by the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method. I105F T. cruzi CYP51 (C = 10 μm in 20 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, 10% glycerol, 500 mm NaCl) was mixed gradually with 1 mm obtusifoliol solution in 45% (w/v) 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPCD); incubated 20 min at room temperature; concentrated to 600 μm; diluted 2-fold with 5 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.2; preincubated with 0.02 mm n-tetradecyl-β-d-maltoside (Hampton Research) and 5.5 mm tris(carboxyethyl)phosphine; and centrifuged to remove the precipitate. The crystallization drop consisted of equal volumes of obtusifoliol-bound protein and mother liquor (0.2 m calcium acetate hydrate, pH 7.3, 20% PEG 3350 (w/v), pH 7.3). Crystals grew at 21 °C within several days and, after harvesting, were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, using mother liquor with 30% glycerol (v/v) as a cryoprotectant. The X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Advanced Light Source Beamline 21-ID-F. The structure was solved by molecular replacement with the PHASER software (CCP4 Program Suite (34)) and PDB code 3G1Q as a search model. The refinement was performed with REFMAC (CCP4 Suite), and the model building was carried out with Coot (35)). The data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1. The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 6FMO.

Stability assay

Stabilities of human CYP51, WT, and the mutants were monitored as the decrease in the P450 content upon incubation of the 2 μm protein samples in 200 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, 10% glycerol (v/v), and 0.1% Triton X-100 (v/v) in a Thermal Cycler 480 (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) at 42 °C. The aliquots were taken after 5, 10, and 20 min. The spectra were recorded on a dual-beam Shimadzu UV-240IPC spectrophotometer. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

Enzymatic activity assays

Enzymatic activity was reconstituted as previously described (6, 17) using radiolabeled (3-3H) sterol substrates added from a 0.5 mm solution in 45% (w/v) HPCD (lanosterol for human CYP51 and eburicol for T. cruzi CYP51, specific activity ∼4,000 dpm/nmol), and CPR as the electron donor (rat for human CYP51 and T. brucei for T. cruzi CYP51). The standard reaction mixture contained a 1:2 molar ratio of P450:CPR (final concentrations were 0.5 and 1 μm for human and T. cruzi CYP51, respectively), 100 μm l-α-1,2-dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DLPC), 0.4 mg/ml isocitrate dehydrogenase, and 25 mm sodium isocitrate in 20 mm MOPS buffer (pH 7.4) containing 50 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, and 10% glycerol (v/v). After the addition of the radiolabeled substrates, the mixture was preincubated for 2 min at 37 °C in a shaking water bath. The reaction was initiated by addition of 100 μm NADPH and stopped by extraction of the sterols with ethyl acetate. The extracted sterols were analyzed by a reversed-phase HPLC system (Waters) equipped with a β-RAM detector (INUS Systems). The activity was monitored as the percentage of the product formation (4,4-dimethylcholesta-8,14,24-trien-3β-ol from lanosterol (by human CYP51) and 24-methylene-4,4-dimethylcholesta-8,14-dien-3β-ol from eburicol (by T. cruzi CYP51) (see the formulas in Fig. S1)). Michaelis–Menten parameters were calculated using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA), with the reaction rates (nmol product formed/nmol P450/min) being plotted versus total substrate concentration and using nonlinear regression (hyperbolic fits).

Substrate binding assays

Spectral titration of 2 μm CYP51 with the substrates (lanosterol for human, WT, H314A, D231A, and H314A/D231A; eburicol for T. cruzi, WT, and R124A) was carried out in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 100 mm NaCl. The high-spin form content was estimated from the absolute spectra as the ratio (ΔA393–470/ΔA418–470) and from the difference spectra with the response of 0.11 absorbance units/nmol P450 corresponding to a 100% low-to-high spin transition (6, 17). The Kd values were calculated by fitting the data for the substrate-induced absorbance changes in the difference spectra Δ(Amax − Amin) versus substrate concentration to the Morrison equation in GraphPad Prism 6, using nonlinear regression (of hyperbolic fits).

Reduction of ferric CYP51

Reduction rates were estimated anaerobically in a stopped-flow spectrophotometer (OLIS RSM-1000, On-Line Instrument Systems, Bogart, GA) at 23 °C as described previously (36). One syringe of the instrument included 2.0 μm I105F T. cruzi CYP51, 4.0 μm T. brucei CPR, 300 μm DLPC, 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and 10 μm eburicol, added from a 0.5 mm solution in 45% (w/v) HPCD. The other syringe contained 300 μm NADPH in 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). A “scrubbing” system composed of 1 unit ml−1 protocatechuate dioxygenase and 0.5 mm protocatechuate (to remove residual oxygen) was included in both all-glass tonometers and the drive syringes on both sides (37). The samples were prepared under an anaerobic atmosphere of carbon monoxide.

The stopped-flow instrument was operated in the rapid-scanning mode with a 400 lines mm−1, >500-nm grating, centered at 450 nm. Reduced (ferrous) T. cruzi CYP51 was trapped by the addition of the carbon monoxide, yielding a spectral change at 450 nm, and the data were collected up to 120 s, with signal averaging of 62 scans s−1. The data (ΔA450) were fit to a single-exponential fit using the OLIS GlobalWorks software. With each CY51 experiment, results from at least four separate reactions (rates) were averaged and used to calculate a rate ± S.D. using a single-exponential fit.

Author contributions

T. Y. H., Z. W., W. D. N., F. P. G., M. R. W., and G. I. L. formal analysis; T. Y. H. and Z. W. validation; T. Y. H., Z. W., F. P. G., and G. I. L. investigation; W. D. N., F. P. G., and G. I. L. writing-review and editing; M. R. W. and G. I. L. conceptualization; G. I. L. supervision; G. I. L. funding acquisition; G. I. L. visualization; G. I. L. writing-original draft; P. M. F. synthesis of obtusifoliol and eburicol; S. A. C. stopped-flow experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Vanderbilt University is a member institution of the Life Sciences Collaborative Access Team at Sector 21 of the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne, IL). Use of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory was supported by the United States Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

* This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM067871 (to G. I. L. and F. P. G.). Synthesis of obtusifoliol and eburicol was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R33 AI119782 (to W. D. N.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Movie S1 and Figs. S1–S9.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 6FMO) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- CYP or P450

- cytochrome P450

- CYP51

- sterol 14α-demethylase

- CPR

- NADPH–cytochrome P450 reductase

- RMSD

- root mean square deviation

- HPCD

- 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin

- DLPC

- l-α-1,2-dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- MCP

- 14α-methylenecyclopropyl-Δ7-24,25-dihydrolanosterol.

References

- 1. Lepesheva G. I., and Waterman M. R. (2007) Sterol 14α-demethylase cytochrome P450 (CYP51), a P450 in all biological kingdoms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1770, 467–477 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guengerich F. P. (2007) Mechanisms of cytochrome P450 substrate oxidation: MiniReview. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 21, 163–168 10.1002/jbt.20174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hargrove T. Y., Wawrzak Z., Liu J., Waterman M. R., Nes W. D., and Lepesheva G. I. (2012) Structural complex of sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) with 14α-methylenecyclopropyl-Δ7–24,25-dihydrolanosterol. J. Lipid Res. 53, 311–320 10.1194/jlr.M021865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rittle J., and Green M. T. (2010) Cytochrome P450 compound I: capture, characterization, and C–H bond activation kinetics. Science 330, 933–937 10.1126/science.1193478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lepesheva G. I., Friggeri L., and Waterman M. R. (2018) CYP51 as drug targets for fungi and protozoan parasites: past, present and future. Parasitology 145, 1820–1836 10.1017/S0031182018000562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hargrove T. Y., Friggeri L., Wawrzak Z., Sivakumaran S., Yazlovitskaya E. M., Hiebert S. W., Guengerich F. P., Waterman M. R., and Lepesheva G. I. (2016) Human sterol 14α-demethylase as a target for anticancer chemotherapy: towards structure-aided drug design. J. Lipid Res. 57, 1552–1563 10.1194/jlr.M069229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nelson D. R. (1999) Cytochrome P450 and the individuality of species. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 369, 1–10 10.1006/abbi.1999.1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoshida Y., Aoyama Y., Noshiro M., and Gotoh O. (2000) Sterol 14-demethylase P450 (CYP51) provides a breakthrough for the discussion on the evolution of cytochrome P450 gene superfamily. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 273, 799–804 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lepesheva G. I., Park H. W., Hargrove T. Y., Vanhollebeke B., Wawrzak Z., Harp J. M., Sundaramoorthy M., Nes W. D., Pays E., Chaudhuri M., Villalta F., and Waterman M. R. (2010) Crystal structures of Trypanosoma brucei sterol 14α-demethylase and implications for selective treatment of human infections. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 1773–1780 10.1074/jbc.M109.067470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lepesheva G. I., and Waterman M. R. (2011) Structural basis for conservation in the CYP51 family. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1814, 88–93 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hargrove T. Y., Friggeri L., Wawrzak Z., Qi A., Hoekstra W. J., Schotzinger R. J., York J. D., Guengerich F. P., and Lepesheva G. I. (2017) Structural analyses of Candida albicans sterol 14α-demethylase complexed with azole drugs address the molecular basis of azole-mediated inhibition of fungal sterol biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 6728–6743 10.1074/jbc.M117.778308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lepesheva G. I., Hargrove T. Y., Anderson S., Kleshchenko Y., Furtak V., Wawrzak Z., Villalta F., and Waterman M. R. (2010) Structural insights into inhibition of sterol 14α-demethylase in the human pathogen Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 25582–25590 10.1074/jbc.M110.133215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hargrove T. Y., Wawrzak Z., Lamb D. C., Guengerich F. P., and Lepesheva G. I. (2015) Structure-functional characterization of cytochrome P450 sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51B) from Aspergillus fumigatus and molecular basis for the development of antifungal drugs. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 23916–23934 10.1074/jbc.M115.677310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hargrove T. Y., Wawrzak Z., Alexander P. W., Chaplin J. H., Keenan M., Charman S. A., Perez C. J., Waterman M. R., Chatelain E., and Lepesheva G. I. (2013) Complexes of Trypanosoma cruzi sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) with two pyridine-based drug candidates for Chagas disease: structural basis for pathogen selectivity. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 31602–31615 10.1074/jbc.M113.497990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lepesheva G. I., Ott R. D., Hargrove T. Y., Kleshchenko Y. Y., Schuster I., Nes W. D., Hill G. C., Villalta F., and Waterman M. R. (2007) Sterol 14α-demethylase as a potential target for antitrypanosomal therapy: enzyme inhibition and parasite cell growth. Chem. Biol. 14, 1283–1293 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lepesheva G. I., Seliskar M., Knutson C. G., Stourman N. V., Rozman D., and Waterman M. R. (2007) Conformational dynamics in the F/G segment of CYP51 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis monitored by FRET. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 464, 221–227 10.1016/j.abb.2007.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lepesheva G. I., Zaitseva N. G., Nes W. D., Zhou W., Arase M., Liu J., Hill G. C., and Waterman M. R. (2006) CYP51 from Trypanosoma cruzi: a phyla-specific residue in the B' helix defines substrate preferences of sterol 14α-demethylase. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 3577–3585 10.1074/jbc.M510317200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hargrove T. Y., Wawrzak Z., Liu J., Nes W. D., Waterman M. R., and Lepesheva G. I. (2011) Substrate preferences and catalytic parameters determined by structural characteristics of sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) from Leishmania infantum. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 26838–26848 10.1074/jbc.M111.237099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Monk B. C., Tomasiak T. M., Keniya M. V., Huschmann F. U., Tyndall J. D., O'Connell J. D. 3rd, Cannon R. D., McDonald J. G., Rodriguez A., Finer-Moore J. S., and Stroud R. M. (2014) Architecture of a single membrane spanning cytochrome P450 suggests constraints that orient the catalytic domain relative to a bilayer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 3865–3870 10.1073/pnas.1324245111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sen K., and Hackett J. C. (2009) Molecular oxygen activation and proton transfer mechanisms in lanosterol 14α-demethylase catalysis. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 8170–8182 10.1021/jp902932p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vidakovic M., Sligar S. G., Li H., and Poulos T. L. (1998) Understanding the role of the essential Asp251 in cytochrome p450cam using site-directed mutagenesis, crystallography, and kinetic solvent isotope effect. Biochemistry 37, 9211–9219 10.1021/bi980189f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tripathi S., Li H., and Poulos T. L. (2013) Structural basis for effector control and redox partner recognition in cytochrome P450. Science 340, 1227–1230 10.1126/science.1235797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Denisov I. G., Baas B. J., Grinkova Y. V., and Sligar S. G. (2007) Cooperativity in cytochrome P450 3A4: linkages in substrate binding, spin state, uncoupling, and product formation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 7066–7076 10.1074/jbc.M609589200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Conner K. P., Woods C. M., and Atkins W. M. (2011) Interactions of cytochrome P450s with their ligands. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 507, 56–65 10.1016/j.abb.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Conner K. P., Schimpf A. M., Cruce A. A., McLean K. J., Munro A. W., Frank D. J., Krzyaniak M. D., Ortiz de Montellano P., Bowman M. K., and Atkins W. M. (2014) Strength of axial water ligation in substrate-free cytochrome P450s is isoform dependent. Biochemistry 53, 1428–1434 10.1021/bi401547j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lockart M. M., Rodriguez C. A., Atkins W. M., and Bowman M. K. (2018) CW EPR parameters reveal cytochrome P450 ligand binding modes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 183, 157–164 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2018.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hannemann F., Bichet A., Ewen K. M., and Bernhardt R. (2007) Cytochrome P450 systems: biological variations of electron transport chains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1770, 330–344 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sevrioukova I. F., Li H., Zhang H., Peterson J. A., and Poulos T. L. (1999) Structure of a cytochrome P450–redox partner electron-transfer complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 1863–1868 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Strushkevich N., MacKenzie F., Cherkesova T., Grabovec I., Usanov S., and Park H.-W. (2011) Structural basis for pregnenolone biosynthesis by the mitochondrial monooxygenase system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 10139–10143 10.1073/pnas.1019441108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hiruma Y., Hass M. A., Kikui Y., Liu W. M., Ölmez B., Skinner S. P., Blok A., Kloosterman A., Koteishi H., Löhr F., Schwalbe H., Nojiri M., and Ubbink M. (2013) The structure of the cytochrome p450cam-putidaredoxin complex determined by paramagnetic NMR spectroscopy and crystallography. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 4353–4365 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mast N., White M. A., Bjorkhem I., Johnson E. F., Stout C. D., and Pikuleva I. A. (2008) Crystal structures of substrate-bound and substrate-free cytochrome P450 46A1, the principal cholesterol hydroxylase in the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 9546–9551 10.1073/pnas.0803717105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mast N., Annalora A. J., Lodowski D. T., Palczewski K., Stout C. D., and Pikuleva I. A. (2011) Structural basis for three-step sequential catalysis by the cholesterol side chain cleavage enzyme CYP11A1. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 5607–5613 10.1074/jbc.M110.188433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sevrioukova I. F., and Poulos T. L. (2017) Structural basis for regiospecific midazolam oxidation by human cytochrome P450 3A4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 486–491 10.1073/pnas.1616198114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Potterton E., Briggs P., Turkenburg M., and Dodson E. (2003) A graphical user interface to the CCP4 program suite. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59, 1131–1137 10.1107/S0907444903008126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., and Cowtan K. (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 10.1107/S0907444910007493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guengerich F. P., and Johnson W. W. (1997) Kinetics of ferric cytochrome P450 reduction by NADPH–cytochrome P450 reductase: rapid reduction in the absence of substrate and variations among cytochrome P450 systems. Biochemistry 36, 14741–14750 10.1021/bi9719399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Patil P. V., and Ballou D. P. (2000) The use of protocatechuate dioxygenase for maintaining anaerobic conditions in biochemical experiments. Anal. Biochem. 286, 187–192 10.1006/abio.2000.4802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.