Abstract

Introduction

Discordance of various aspects of sexual orientation has been mostly studied in young adults or in small samples of heterosexual men. Studies focusing on concordance and discordance of aspects of sexual orientation in representative samples of middle-aged men including homosexual men are scarce.

Aim

To investigate concordant and discordant sexual behavior in 45-year-old German men with a special focus on homosexual identified men.

Methods

Data for this cross-sectional study were collected within the German Male Sex-Study. Participants were 45-year-old Caucasian males from the general population. Men self-reported on sexual identity, sexual experience, and current sexual behavior. Associations between sexual identity, experience, and behavior were analyzed using the chi-square test.

Main Outcome Measure

Associations of sexual identity with sexual experience and behavior in a community-based sample of men, and discordance of sexual identity and behavior especially in the subgroup of homosexual men.

Results

12,354 men were included in the study. 95.1% (n = 11.749) self-identified as heterosexual, 3.8% (n = 471) as homosexual, and 1.1% (n = 134) as bisexual. Sexual identity was significantly associated with sexual experience and behavior. 85.5% of all men had recently been sexually active, but prevalence of sexual practices varied. In hetero- and bisexuals, vaginal intercourse was the most common sexual practice, whereas oral sex was the most common in homosexuals. A discordance of sexual identity was especially found in homosexual men: 5.5% of homosexuals only had sexual experiences with women, and 10.3% of homosexuals recently had vaginal intercourse. In this latter subgroup, only one-quarter ever had sexual experience with a man, and three-quarters had only engaged in sexual activity with a woman.

Conclusion

Sexual identity is associated with differences in sexual experience and behavior in German middle-aged men. A considerable proportion of homosexual identified men live a heterosexual life.

Goethe VE, Angerer H, Dinkel A, et al. Concordance and Discordance of Sexual Identity, Sexual Experience, and Current Sexual Behavior in 45-Year-Old-Men: Results From the German Male Sex-Study. Sex Med 201;6:282–290.

Key Words: German Male Sex-Study, Homosexual, Intercourse, Sexual Activity, Sexual Behavior, Sexual Experience, Sexual Identity

Introduction

Since the beginning of modern sex research, there has been a consensus that the assessment of sexual orientation is complex, and simply categorizing men into heterosexual and homosexual does not necessarily correspond with the actual sexual behavior. Alfred Kinsey was one of the first to respond to this complexity when he introduced the Kinsey Scale in 1948. The Kinsey Scale categorized men and women not solely into exclusively heterosexual or exclusively homosexual categories but also allowed for 5 further “in-between” categories.1 Since then, numerous other rating scales have been developed to assess sexual orientation,2, 3, 4, 5 with the Klein Sexual Orientation Grid probably being the most thorough because it assesses 7 different aspects of sexual orientation in the past, in the present, and as an ideal.2

To facilitate sex research, most studies today have focused on at least 1 of the following 3 aspects to assess sexual orientation: self-reported sexual identity, sexual behavior, and sexual attraction,6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 many of them finding a discordance between those 3 aspects.7, 12, 13, 14 Studies exploring the sexuality of adolescents or young adults have found this discordance to be particularly prevalent.6, 10, 15 For instance, Mustanski et al10 report that almost one-half of homosexual adolescents have had experiences with the other sex. Although in adolescence these discordances can be attributed to the development of sexuality and the search for sexual identity,16, 17, 18, 19 various studies have found them to be a risk factor for mental health problems, such as for depression or even higher suicide risk.19, 20

Research assessing discordance of the aspects of sexual orientation in adult men has mostly been conducted only in heterosexual men and has found discordant heterosexual men to have a higher risk for mental health problems as well.21, 22, 23, 24 However, these studies were conducted on very small samples, and discordant homosexual men were almost entirely excluded. In light of the lack of available research in community-based samples, the aim of the present study was to investigate concordance and discordance of self-reported sexual identity and sexual behavior and the association that sexual identity has with sexual behavior in a community-based sample of middle-aged men. Considering that many studies have focused on heterosexual men with discordant behavior only, this study sought to specifically examine the sexual behavior of homosexual identified men.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Data for the German Male Sex-Study (GMS-Study) are collected within the PROBASE trial, a German prostate cancer screening trial that has been described in detail elsewhere.25 Starting in spring 2014, 45-year-old men residing in the area of the 4 study centers (Dusseldorf, Hannover, Heidelberg, Munich) have been recruited to participate in a prostate-specific antigen value–based risk-adapted prostate cancer screening. After obtaining informed consent, men are asked to fill out questionnaires assessing sociodemographic data, lifestyle, psychological factors, and sexuality. In addition, a clinical interview and a short physical examination are performed. Recruitment is based on a random sample of 45-year-old men from the residents’ registration offices data files, which contain all addresses of people living in Germany. Until 2020, 50,000 men will be enrolled. With a follow-up of 15 years for each participant, data collection will be completed in 2035. The PROBASE trial and all of its related projects have been approved by the ethics committees of the 4 study centers.

The GMS-Study focuses on sexual behavior and sexual dysfunctions of the participants and includes all men who indicate their sexual identity. Data for the present analysis were collected within the first 2 years of the study (April 2014 to April 2016). Owing to small sample sizes, all non-Caucasian men were excluded.

Measures

Sociodemographic Data

Men indicated whether they were married (married, married but not living with spouse, single, divorced, widowed, don’t know) or had a steady partner (yes, no), the duration of the current partnership in months (categorized as 0, <6, 6 to <12, 12 to <36, 36 to <60, 60 to <120, ≥120), whether they were living with their partner (yes, permanently; yes, temporarily; no, separate homes), and whether they had children (yes, no). Further sociodemographic data included the level of education (low defined as less than high school, intermediate defined as high school, high defined as more than high school), the employment status (full time, part time, unemployed), and the self-perceived economic status (very good, good, satisfactory, rather bad, bad). Finally, religion was also inquired by 1 question (Christian, Muslim, Jewish, others, not religious).

Sexual Identity

Sexual identity was assessed by the following item: “What is your sexual identity?” Possible answers were “heterosexual,” “homosexual,” and “bisexual.”

Sexual Experience

Before asking about further sexuality-related items, “sexual activity” and “sexually active,” respectively, were defined as any form of voluntary sexual behavior with another person with or without penetration or orgasm.26 The men were informed that this definition should be applied to all questions about sexuality. Variables concerning partnered sexual experience were lifetime sexual partners (0, 1, 2-10, 11-30, >30), ever having had a sexual experience with a woman/with a man, and sexual experience only with women/only with men/with both/with neither.27 The 2 latter variables were determined by the combination of the answer to the following questions: “When were you first sexually active with a woman/with a man?” (age).

Current Sexual Activity

Men were asked whether they had masturbated in the past 3 months (no, yes). Furthermore, in men who reported to have been sexually active in the past 3 months, partnered sexual activity was assessed. Assessed partnered sexual activities were vaginal sex, oral sex, and anal sex (no, yes).

To specifically analyze homosexual men with discordant sexual behavior, we defined a subgroup of homosexual men who only had sexual experience with women and had vaginal intercourse in the past 3 months. This group was referred to as “hidden homosexuals.”

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted by calculating counts and percentages for all categorical variables. The chi-square test was used to compare sexual identity groups on descriptive variables. For continuous variables, mean, median, and SD were provided. All statistical tests were carried out with STAT version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and were performed at a 0.05 significance level.

Results

Between April 2014 and April 2016, 16,605 men were recruited within the PROBASE trial. Of those, 12,646 indicated their sexual identity and were therefore included in the GMS-Study. After excluding 292 non-Caucasian men, 12,354 men were left for further analysis.

Sexual Identity and Sexual Experience

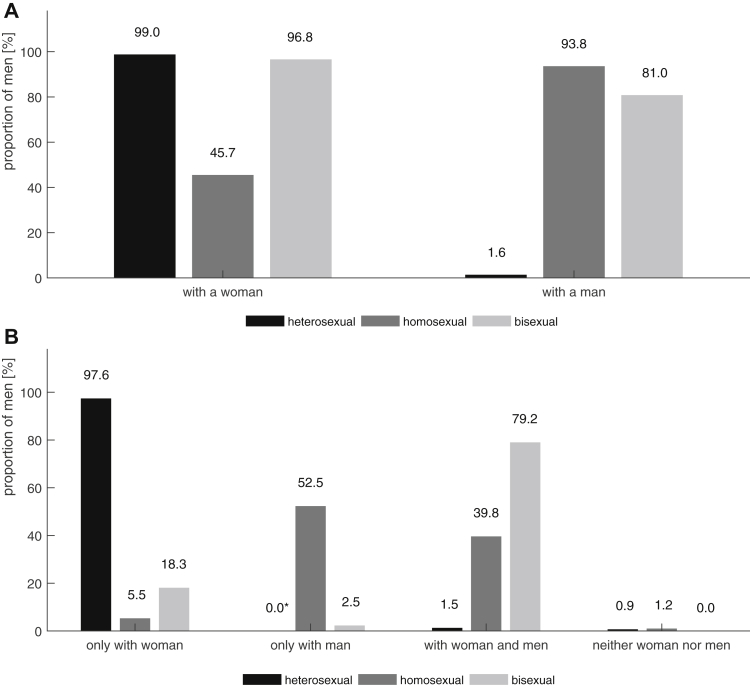

Sociodemographic data and descriptive data on sexual experience and behavior are shown in Tables 1 and 2. 95.1% (n = 11,749) of all men self-identified as heterosexual, 3.8% (n = 471) as homosexual, and 1.1% (n = 134) as bisexual. Irrespective of sexual identity, men had their first sexual experience with women at approximately 18 years of age. First sexual experiences with a man were made, on average, 2 years later, with bisexuals being the latest (Table 2). Almost all hetero- and bisexual men in the survey reported having a sexual experience with a woman. In addition, nearly one-half of homosexual men reported having engaged in sexual activity with a woman. Regarding sexual experience with a man, heterosexuals differed considerably from homo- and bisexual men (1.6% vs 93.8% and 81.0%, respectively; Figure 1A).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population

| Variable | Overall |

Heterosexual |

Homosexual |

Bisexual |

Hidden homosexuals |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Married | 66.0 | 7,978 | 67.7 | 7,781 | 30.1 | 139 | 43.9 | 58 | 73.7 | 14 |

| Married, but not living with spouse | 2.3 | 272 | 2.3 | 261 | 1.3 | 6 | 3.8 | 5 | 5.3 | 1 |

| Single | 22.9 | 2,764 | 21.1 | 2,423 | 63.2 | 292 | 37.1 | 49 | 5.3 | 1 |

| Divorced | 8.5 | 1,029 | 8.6 | 987 | 5.0 | 23 | 14.4 | 19 | 15.8 | 3 |

| Widowed | 0.3 | 32 | 0.3 | 30 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Don’t know | 0.1 | 15 | 0.1 | 14 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Steady partner | ||||||||||

| Yes | 84.9 | 10,480 | 85.7 | 10,058 | 70.7 | 333 | 66.4 | 89 | 94.7 | 18 |

| No | 15.1 | 1,864 | 14.3 | 1,681 | 29.3 | 138 | 33.6 | 45 | 5.3 | 1 |

| Duration of current partnership | ||||||||||

| 0 | 15.6 | 1,820 | 14.8 | 1,639 | 30.4 | 137 | 33.9 | 44 | 0.0 | 0 |

| <6 | 0.5 | 58 | 0.5 | 54 | 0.7 | 3 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 6–12 | 1.4 | 161 | 1.4 | 152 | 1.3 | 6 | 2.3 | 3 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 12 to <36 | 3.2 | 372 | 3.1 | 346 | 4.7 | 21 | 3.9 | 5 | 10.5 | 2 |

| 36 to <60 | 4.3 | 500 | 4.3 | 475 | 4.4 | 20 | 3.9 | 5 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 60 to <120 | 12.0 | 1,405 | 12.0 | 1,330 | 14,7 | 66 | 6.9 | 9 | 15.8 | 3 |

| ≥120 | 63.1 | 7,373 | 64.0 | 7,113 | 43.8 | 197 | 48.5 | 63 | 68.4 | 13 |

| Living with partner | ||||||||||

| Yes, permanently | 90.7 | 9,241 | 91.3 | 8,916 | 76,7 | 254 | 82.6 | 71 | 100.0 | 17 |

| Yes, temporarily | 6.2 | 636 | 5.8 | 569 | 16.9 | 56 | 12.8 | 11 | 0.0 | 0 |

| No, separate homes | 3.1 | 311 | 2.9 | 286 | 6.3 | 21 | 4.7 | 4 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Children | ||||||||||

| Yes | 77.7 | 8,097 | 79.5 | 7,991 | 14.5 | 40 | 64.7 | 66 | 83.3 | 15 |

| No | 22.3 | 2,329 | 20.5 | 2,057 | 85.5 | 236 | 35.3 | 36 | 16.7 | 3 |

| Education level | ||||||||||

| Low | 12.5 | 1,508 | 12.4 | 1,432 | 9.7 | 45 | 23.3 | 31 | 5.3 | 1 |

| Intermediate | 25.7 | 3,107 | 25.6 | 2,947 | 28.7 | 133 | 20.3 | 27 | 26.3 | 5 |

| High | 61.9 | 7,490 | 62.0 | 7,129 | 61.6 | 286 | 56.4 | 75 | 68.4 | 13 |

| Employment status | ||||||||||

| Full time | 91.6 | 11,178 | 92.1 | 10,685 | 82.7 | 386 | 82.3 | 107 | 94.7 | 18 |

| Part time | 4.3 | 526 | 4.0 | 464 | 10.9 | 51 | 8.5 | 11 | 5.3 | 1 |

| Unemployed | 4.1 | 499 | 3.9 | 457 | 6.4 | 30 | 9.2 | 12 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Self-perceived economic status | ||||||||||

| Very good | 19.8 | 2,421 | 19.6 | 2,276 | 26.3 | 124 | 16.0 | 21 | 15.8 | 3 |

| Good | 55.5 | 6,783 | 55.7 | 6,480 | 51.4 | 242 | 46.6 | 61 | 63.2 | 12 |

| Satisfactory | 20.6 | 2,522 | 20.7 | 2,410 | 15.92 | 75 | 28.2 | 37 | 21.1 | 4 |

| Rather Bad | 3.0 | 371 | 2.9 | 341 | 4.2 | 20 | 7.6 | 10 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Bad | 1.1 | 136 | 1.1 | 124 | 2.1 | 10 | 1.5 | 2 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Christian | 74.8 | 5,283 | 75.3 | 5,069 | 60. | 156 | 73.4 | 58 | 90.9 | 10 |

| Muslim | 2.8 | 197 | 2.8 | 190 | 1.2 | 3 | 5.1 | 6 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Jewish | 0.1 | 8 | 0.1 | 7 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Others | 0.3 | 22 | 0.3 | 22 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Not religious | 22.0 | 1,558 | 21.4 | 1,441 | 38.4 | 100 | 21.5 | 17 | 9.1 | 1 |

Percentages not adding up to 100% are attributed to rounding.

Table 2.

Sexual behavior of the study population

| Variables | Overall |

Heterosexual |

Homosexual |

Bisexual |

Hidden homosexuals |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| Sexual identity | ||||||||||

| Heterosexual | 95.1 | 11,749 | ||||||||

| Homosexual | 3.8 | 471 | ||||||||

| Bisexual | 1.1 | 134 | ||||||||

| Sexual experience | ||||||||||

| With a woman | 97.1 | 11,340 | 99.0 | 11,024 | 45.7 | 194 | 96.8 | 122 | 100.0 | 19 |

| With a man | 6.1 | 682 | 1.6 | 164 | 93.8 | 420 | 81.0 | 98 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Only with women | 93.3 | 10,226 | 97.6 | 10,181 | 5.54 | 23 | 18.3 | 22 | 100.0 | 19 |

| Only with men | 2.1 | 226 | 0.0 | 1 | 53.5 | 222 | 2.5 | 5 | 0.0 | 0 |

| With both genders | 3.8 | 415 | 1.5 | 155 | 39.8 | 165 | 79.2 | 95 | 0.0 | 0 |

| With neither | 0.9 | 98 | 0.9 | 93 | 1.2 | 5 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Lifetime sexual partners | ||||||||||

| 0 | 0.7 | 78 | 0.6 | 70 | 0.5 | 10 | 4.7 | 6 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1 | 8.6 | 1,006 | 8.9 | 992 | 2.3 | 10 | 3.1 | 4 | 15.8 | 3 |

| 2–3 | 18.6 | 2,175 | 19.2 | 2,140 | 5.8 | 26 | 7.0 | 9 | 10.5 | 2 |

| 4–5 | 19.8 | 2,315 | 20.2 | 2,253 | 10.8 | 48 | 10.9 | 14 | 31.6 | 6 |

| 6–10 | 22.2 | 2,603 | 22.6 | 2,523 | 11.0 | 49 | 24.4 | 31 | 10.5 | 2 |

| 11–15 | 11.3 | 1,330 | 11.5 | 1,279 | 9.7 | 43 | 6.2 | 8 | 10.5 | 2 |

| 16–20 | 6.6 | 772 | 6.5 | 723 | 7.9 | 35 | 10.9 | 14 | 5.3 | 1 |

| 21–30 | 4.6 | 544 | 4.5 | 500 | 8.1 | 36 | 6.3 | 8 | 10.5 | 2 |

| >30 | 7.7 | 901 | 6.0 | 671 | 44.0 | 196 | 26.6 | 34 | 5.3 | 1 |

| Solo-masturbation (past 3 mo) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 78.5 | 9,018 | 77.7 | 8,470 | 94.3 | 427 | 93.1 | 121 | 89.5 | 17 |

| No | 21.5 | 2,466 | 22.3 | 2,431 | 5.7 | 26 | 6.9 | 9 | 10.5 | 2 |

| Partnered sexual activity (past 3 mo) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 85.5 | 10,348 | 85.6 | 9,843 | 84.6 | 394 | 84.1 | 111 | 100.0 | 19 |

| No | 14.5 | 1,752 | 14.4 | 1,659 | 15.6 | 72 | 15.9 | 21 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Vaginal sex (past 3 mo) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 95.0 | 9,367 | 97.6 | 9,257 | 10.3 | 29 | 81.0 | 81 | 100.0 | 19 |

| No | 5.0 | 498 | 2.4 | 225 | 89.8 | 254 | 19.0 | 19 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Oral sex (past 3 mo) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 59.4 | 5,692 | 58.0 | 5,283 | 90.9 | 331 | 75.7 | 78 | 77.8 | 14 |

| No | 40.6 | 3,888 | 42.0 | 3,830 | 9.1 | 33 | 24.3 | 25 | 22.2 | 4 |

| Anal sex (past 3 mo) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 9.7 | 916 | 7.2 | 643 | 64.0 | 235 | 39.2 | 38 | 5.6 | 1 |

| No | 90.1 | 8,540 | 92.9 | 8,349 | 36.0 | 132 | 60.8 | 59 | 94.4 | 17 |

| Mean age at first sexual experience | Mean (SD) | M | Mean (SD) | M | Mean (SD) | M | Mean (SD) | M | Mean (SD) | M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With a woman | 18.3 (3.4) | 18.0 | 18.2 (3.4) | 18.0 | 18.5 (3.1) | 18.0 | 18.2 (3.6) | 18.0 | 18.8 (3.8) | 18.0 |

| With a man | 20.7 (6.6) | 19.0 | 20.4 (7.7) | 18.0 | 20.2 (5.4) | 19.0 | 22.9 (8.9) | 20 | — | — |

Percentages not adding up to 100% are attributed to rounding.

M = median.

Figure 1.

A, Proportion of men with sexual experience with a woman/a man in association with sexual identity (P < .001). B, Proportion of men with sexual experience in association with sexual identity (P < .001). *n = 1.

5.5% of the homosexual men had sexual experiences only with women, and 20.8% of the bisexual men had sexual experiences with either only women or men but not both. Most bisexual and 39.8% of homosexual men had been sexually active with both women and men (Figure 1B).

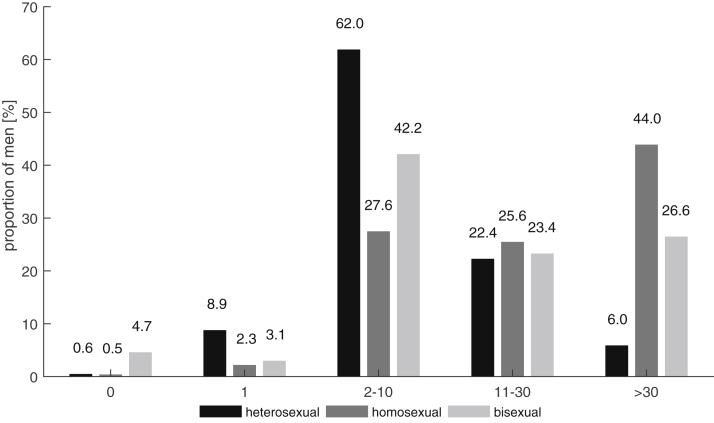

Concerning lifetime sexual partners, most heterosexuals had up to 10 sexual partners up to the age of 45 years. Roughly one-third of homo- and one-half of bisexual men also reported up to 10 sexual partners. More than 30 lifetime sexual partners were reported by 44.0% of homo- and about a quarter of bisexual men, whereas only 6.0% of heterosexual men stated that they had been sexually active with more than 30 different partners (Figure 2). All observed differences were highly significant (P < .001).

Figure 2.

Proportion of men with 0, 1, 2–10, 11–30 or >30 lifetime sexual partners in association with sexual identity (P < .001).

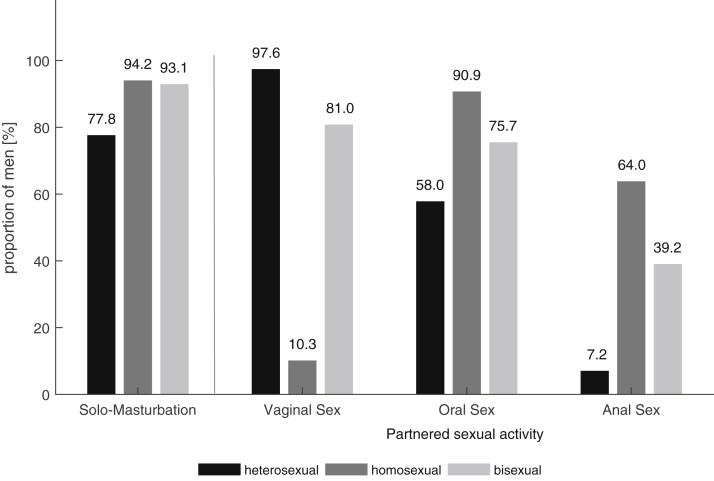

Sexual Behavior in the Past 3 Months

More than three-quarters of all men had masturbated in the past 3 months, with particularly high numbers in homo- and bisexual men (94.2% and 93.1%, respectively, vs 77.8% in heterosexuals). In addition, most men (85.5%) had been sexually active in the past 3 months, with no difference regarding sexual identity (P = .74). Nearly all sexually active hetero- and four-fifths of bisexual men had vaginal intercourse in the past 3 months (97.7% and 81.0%, respectively). Of homosexual men, 10.3% also reported on vaginal sex. Oral sex was the most common partnered sexual behavior among the homosexual men, with an average of 91.0%. Further, it was also common among hetero- and bisexual men (58.0% and 75.7%, respectively). Anal sex was the least common sexual activity in hetero- and bisexual men and the second most common in homosexual men (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Proportion of men with solo-masturbation and vaginal, oral, and anal sex in the past 3 months in association with sexual identity (P for all variables <.001).

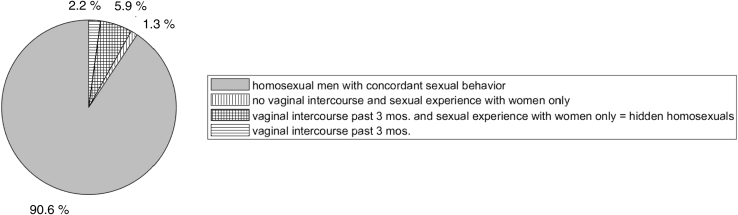

Discordance of Sexual Identity and Sexual Behavior in Homosexual Identified Men

Of the homosexual identified men who provided answers for both the question about vaginal sex in the past 3 months and the gender of previous sexual partners (n = 320), 8.1% had vaginal sex in the past 3 months (n = 26). Furthermore, 7.2% only ever had sexual experience with women (n = 23). The group of hidden homosexuals who not only had sexual experience with a woman recently but only had sexual experience with women in their entire life represented 5.9% of the homosexuals in this subanalysis (n = 19; Figure 4). This equals 73.1% of the homosexual men who had vaginal intercourse in the past 3 months. In comparison to the overall study group, the hidden homosexuals are married more often (79.0% vs 68.3%), more of them have children (83.3% vs 77.7%), and more of them have been with their partner for 10 years or more (68.4% vs 63.1%; Table 1).

Figure 4.

Proportion of homosexual men with concordant or discordant sexual behavior in the past 3 months and in lifetime.

Discussion

This large cross-sectional study provides a basis for understanding the association of middle-aged men’s sexual identity with their sexual experience and behavior in Germany. However, the exceptionality of this analysis does not lie in the analyzed association of sexual identity and behavior but in the detected discordances of sexual identity and sexual behavior. Every 10th homosexual man had engaged in sexual activity with a woman (ie, vaginal sex) in the past 3 months. This finding alone is something that has not been regularly found or even analyzed in other community-based studies. Moreover, when examining the subgroup of homosexual men with vaginal sex in the past 3 months, we found that three-quarters of them never had sexual experience with a man. Furthermore, most of these men were married and have children. Hence, a considerable proportion of homosexual men will probably never live out their sexual identity but live a heterosexual life. This is a finding that other community-based studies have hinted at but have not explicitly proven. The Second Australian Study of Health and Relationships found that 5.5% of men with a non-heterosexual sexual identity never had a same-sex sexual experience.7 However, considering that more than one-third of their sample of homo- and bisexual men were younger than 30 years, it is possible that those were the ones without a same-sex sexual experience. The same applies to a Belgian study of homo- and bisexual men with a mean age of 35 years. 2.9% of the men never had sexual intercourse with a man.28 In a subgroup of 104 homosexual men aged 40–49 years of the US National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior, no men reported having a female sexual partner in the past 12 months.12 However, considering that their data acquisition was partly based on telephone interviews, it is possible that discordance of sexual identity and sexual behavior was underreported owing to social desirability. It can be assumed that the proportion of heterosexually living homosexual men in the United States and other Western countries is similar to that in our sample. Bearing in mind studies showing the impact of discordant sexual behavior on mental health in adolescents, there is a need for future studies assessing the impact in older men as well. Smith et al29 hinted at the possible impact in their study on Australian men aged 16–59 years. Men with non-exclusively heterosexual attraction but exclusively heterosexual experience were twice as often affected from elevated levels of psychosocial distress as other men. Unfortunately, a more in-depth analysis comparing different ages or sexual identities was not provided.29

In addition to the results for sexual experience exclusively with 1 sex, we found that nearly every second homosexual man reported on sexual experience with a woman. Other studies found rates between 24.2% and 67.1%.6, 11, 12 Differences can be explained by divergent inclusion criteria and question wording. For instance, Copen et al11 did not assess numbers for homo- and bisexual men separately, resulting in a higher rate of homo- and bisexual men who reported on sexual experience with women. Furthermore, the US-American National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior only asked about vaginal intercourse, whereas we used a broader definition including sexual activity without intercourse.12

Regarding the number of lifetime sexual partners, our results were in the same scope as previous studies. However, no further study examined the number of lifetime sexual partners in a similar cohort to ours. In a sample of only medical students, Breyer et al15 found a difference in the number of lifetime sexual partners to be already present at a young age, with homosexuals having almost 3 times more sexual partners than hetero- and bisexual students. Corresponding to our results, 2 online surveys with men who have sex with men (MSM) found that almost one-half of heterosexual men already had more than 30 lifetime sexual partners30 and more than one-third had more than 50.28 This latter study also found that 7.8% of MSM had more than 500 sexual partners.28 Almost 5% of bisexual men in our analysis reported having no lifetime sexual partner at all. However, all bisexual men reported having sexual experience with either women or men. This suggests that a sexual partner is generally perceived as a person with whom one has had sexual intercourse, whereas sexual experience or activity is a broader term that does not necessarily imply sexual intercourse.

When analyzing current sexual behavior in association with sexual identity, we found similar results to other studies. Masturbation was a common sexual behavior, particularly present in homo- and bisexual men, that was shown in other community-based studies, such as the US-American National Survey for Sexual Health and Behavior.12 Most men in the present analysis were sexually active in the 3 months prior to inclusion in the study. In both hetero- and bisexual men, vaginal intercourse was the most common partnered sexual behavior. Oral sex was the most common in homosexual men, but it was also highly prevalent in hetero- and bisexual men. Compared to our study, Dodge et al12 and Reece et al31 found lower rates of vaginal intercourse in the past 3 months; however, sexually inactive men were not excluded in their studies. Although a direct comparison of rates of oral and anal sex is difficult, considering that other studies defined oral and anal sex more precisely into giving/insertive and receiving/receptive, the results of the present study are consistent with available evidence in that oral sex is the most common sexual behavior in homosexuals, followed by anal sex.12, 32 With rates between 49.7% and 64.2%, oral sex is also performed by most hetero- and bisexual men.12, 31 Anal sex is the least common among heterosexual men, with prevalence rates of 0.0% to 13.8%.12, 22, 31

The methods of the GMS-Study present both strengths and limitations. Owing to the study design, the assessment of multiple aspects of sexuality in a large age homogenous community–based sample beyond the age of young adults is possible. This enabled us to analyze subgroups that have not been studied previously. However, considering that this is a corollary study of a prostate cancer screening trial, it is likely that men who are particularly interested in preventative health care are overrepresented. Moreover, hetero- and bisexual men and men who are living in a partnership are more inclined to take part in cancer screening programs than homosexual or single men,33, 34, 35 which might have contributed to a sampling bias. This study focused on sexual experience including current sexual behavior but did not assess sexual attraction, which could have provided additional information.

Conclusion

Sexual identity is significantly associated with sexual experience and current sexual behavior. However, specifically in homosexual men, a certain proportion of men have a discordant sexual behavior. 1 of 10 homosexual men has recently had vaginal intercourse. And approximately 6% of men who self-identify as homosexual are hidden homosexuals who live a heterosexual life.

Statement of Authorship

Category 1

-

(a)Conception and Design

- Veronika E. Goethe; Kathleen Herkommer

-

(b)Acquisition of Data

- Veronika E. Goethe; Hannes Angerer; Christian Arsov; Boris Hadaschik; Florian Imkamp; Jürgen E. Gschwend; Kathleen Herkommer

-

(c)Analysis and Interpretation of Data

- Veronika E. Goethe; Andreas Dinkel; Kathleen Herkommer

Category 2

-

(a)Drafting the Article

- Veronika E. Goethe; Kathleen Herkommer

-

(b)Revising It for Intellectual Content

- Veronika E. Goethe; Hannes Angerer; Andreas Dinkel; Christian Arsov; Boris Hadaschik; Florian Imkamp; Jürgen E. Gschwend; Kathleen Herkommer

Category 3

-

(a)Final Approval of the Completed Article

- Veronika E. Goethe; Hannes Angerer; Andreas Dinkel; Christian Arsov; Boris Hadaschik; Florian Imkamp; Jürgen E. Gschwend; Kathleen Herkommer

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding: This work was supported by the German Research Foundation and the Technical University of Munich in the framework of the Open Access Publishing Program. The PROBASE trial is funded by the German Cancer Aid.

References

- 1.Kinsey A.C., Pomeroy W.B., Martin C.E. W. B. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1948. Sexual behavior of the human male. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein F., Sepekoff B., Wolf T.J. Sexual orientation: A multi-variable dynamic process. J Homosex. 1985;11:35–49. doi: 10.1300/J082v11n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shively M.G., De Cecco J.P. Components of sexual identity. J Homosex. 1977;3:41–48. doi: 10.1300/J082v03n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galupo M.P., Lomash E., Mitchell R.C. "All of my lovers fit into this scale": Sexual minority individuals' responses to two novel measures of sexual orientation. J Homosex. 2017;64:145–165. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2016.1174027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis L., Burke D., Ames M.A. Sexual orientation as a continuous variable: A comparison between the sexes. Arch Sex Behav. 1987;16:523–529. doi: 10.1007/BF01541716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oswalt S.B., Wyatt T.J. Sexual health behaviors and sexual orientation in a U.S. national sample of college students. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42:1561–1572. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richters J., Altman D., Badcock P.B. Sexual identity, sexual attraction and sexual experience: The Second Australian Study of Health and Relationships. Sex Health. 2014;11:451–460. doi: 10.1071/SH14117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Everett B.G. Sexual orientation disparities in sexually transmitted infections: Examining the intersection between sexual identity and sexual behavior. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42:225–236. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9902-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vrangalova Z., Savin-Williams R.C. Mostly heterosexual and mostly gay/lesbian: Evidence for new sexual orientation identities. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41:85–101. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9921-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mustanski B., Birkett M., Greene G.J. The association between sexual orientation identity and behavior across race/ethnicity, sex, and age in a probability sample of high school students. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:237–244. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Copen C.E., Chandra A., Febo-Vazquez I. Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual orientation among adults aged 18-44 in the United States: Data from the 2011-2013 National Survey of Family Growth. Natl Health Stat Report. 2016;7:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodge B., Herbenick D., Fu T.C. Sexual behaviors of U.S. men by self-identified sexual orientation: Results from the 2012 National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior. J Sex Med. 2016;13:637–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korchmaros J.D., Powell C., Stevens S. Chasing sexual orientation: A comparison of commonly used single-indicator measures of sexual orientation. J Homosex. 2013;60:596–614. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2013.760324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Igartua K., Thombs B.D., Burgos G. Concordance and discrepancy in sexual identity, attraction, and behavior among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:602–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breyer B.N., Smith J.F., Eisenberg M.L. The impact of sexual orientation on sexuality and sexual practices in North American medical students. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2391–2400. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01794.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eliason M.J. Accounts of sexual identity formation in heterosexual students. Sex Roles. 1995;32:821–834. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tasker F., McCann D. Affirming patterns of adolescent sexual identity: The challenge. J Fam Ther. 1999;21:30–54. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savin-Williams R.C., Ream G.L. Prevalence and stability of sexual orientation components during adolescence and young adulthood. Arch Sex Behav. 2007;36:385–394. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lourie M.A., Needham B.L. Sexual orientation discordance and young adult mental health. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46:943–954. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0553-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Annor F.B., Clayton H.B., Gilbert L.K. Sexual orientation discordance and nonfatal suicidal behaviors in U.S. high school students. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54:530–538. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pathela P., Hajat A., Schillinger J. Discordance between sexual behavior and self-reported sexual identity: A population-based survey of New York City men. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:416–425. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-6-200609190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mercer C.H., Tanton C., Prah P. Changes in sexual attitudes and lifestyles in Britain through the life course and over time: Findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal) Lancet. 2013;382:1781–1794. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62035-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reback C.J., Larkins S. HIV risk behaviors among a sample of heterosexually identified men who occasionally have sex with another male and/or a transwoman. J Sex Res. 2013;50:151–163. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.632101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gattis M.N., Sacco P., Cunningham-Williams R.M. Substance use and mental health disorders among heterosexual identified men and women who have same-sex partners or same-sex attraction: Results from the national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41:1185–1197. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9910-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arsov C., Becker N., Hadaschik B.A. Prospective randomized evaluation of risk-adapted prostate-specific antigen screening in young men: The PROBASE trial. Eur Urol. 2013;64:873–875. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindau S.T., Schumm L.P., Laumann E.O. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyde Z., Flicker L., Hankey G.J. Prevalence of sexual activity and associated factors in men aged 75 to 95 years: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:693–702. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-11-201012070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vansintejan J., Vandevoorde J., Devroey D. The GAy MEn Sex StudieS: Design of an online registration of sexual behaviour of men having sex with men and preliminary results (GAMESSS-study) Cent Eur J Public Health. 2013;21:48–53. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith A.M., Rissel C.E., Richters J. Sex in Australia: Sexual identity, sexual attraction and sexual experience among a representative sample of adults. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2003;27:138–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2003.tb00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shindel A.W., Vittinghoff E., Breyer B.N. Erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation in men who have sex with men. J Sex Med. 2012;9:576–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02585.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reece M., Herbenick D., Schick V. Sexual behaviors, relationships, and perceived health among adult men in the United States: Results from a national probability sample. J Sex Med. 2010;7(Suppl. 5):S291–S304. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenberger J.G., Reece M., Schick V. Sexual behaviors and situational characteristics of most recent male-partnered sexual event among gay and bisexually identified men in the United States. J Sex Med. 2011;8:3040–3050. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conron K.J., Mimiaga M.J., Landers S.J. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1953–1960. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merrill R.M. Demographics and health-related factors of men receiving prostate-specific antigen screening in Utah. Prev Med. 2001;33:646–652. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Jaarsveld C.H., Miles A., Edwards R. Marriage and cancer prevention: Does marital status and inviting both spouses together influence colorectal cancer screening participation? J Med Screen. 2006;13:172–176. doi: 10.1177/096914130601300403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]