Abstract

Background

The preliminary results of our phase II randomized trial reported comparable functional sphincter preservation rates and short-term survival outcomes between patients undergoing total mesorectal excision (TME) with or without preoperative concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT). We now report the long-term results after a median follow-up of 71 months.

Methods

Between March 23, 2008 and August 2, 2012, 192 patients with T3-T4 or node-positive, resectable, mid/low rectal adenocarcinoma were randomly assigned to receive TME with or without preoperative CCRT. The following endpoints were assessed: cumulative rates of local recurrence and distant metastasis, disease-free survival (DFS), and overall survival (OS).

Results

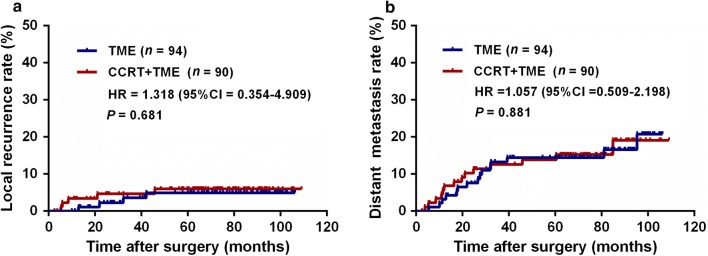

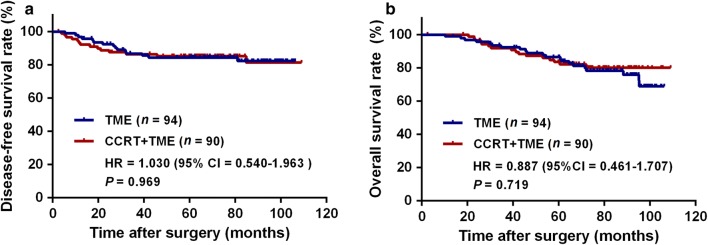

The data of 184 eligible patients were analyzed: 94 patients in the TME group and 90 patients in the CCRT + TME group. In the whole cohort, the 5-year DFS and OS rates were 84.8% and 85.1%, respectively. The 5-year DFS rates were 85.2% in the CCRT + TME group and 84.3% in the TME group (P = 0.969), and the 5-year OS rates were 83.5% in the CCRT + TME group and 86.5% in the TME group (P = 0.719). The 5-year cumulative rates of local recurrence were 6.3% and 5.0% (P = 0.681), and the 5-year cumulative rates of distant metastasis were 15.0% and 15.7% (P = 0.881) in the CCRT + TME and TME groups, respectively. No significant improvements in 5-year DFS and OS were observed with CCRT by subgroup analyses.

Conclusions

Both treatment strategies yielded similar long-term outcomes. A selective policy towards preoperative CCRT is thus recommended for rectal cancer patients if high-quality TME surgery and enhanced chemotherapy can be performed.

Trial registration ChiCTR-TRC-08000122. Registered 16 July 2008

Keywords: Rectal cancer, Total mesorectal excision, Chemoradiotherapy, Long-term outcomes, Phase II randomized trial

Introduction

Current clinical guidelines suggest that surgical resection still represents the most effective treatment measure for curing patients with mid/low rectal cancer [1, 2]. Total mesorectal excision (TME) has been recognized as the preferred surgical method for resectable rectal cancer, and it reduced locoregional recurrence rates to below 10% and improved cancer-free survival rates to over 70% [3, 4]. To further optimize local treatment, preoperative concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) consisting of fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy and concurrent radiotherapy has been widely performed before TME. Although local recurrence has been significantly reduced to < 7%, 5-year distant metastasis rates are still beyond 20% in mid/low rectal cancer patients after preoperative chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) followed by TME [5–7]. In addition, a certain proportion of patients experience CCRT-related adverse events, including leucopenia, thrombocytopenia, radiation proctitis, anastomotic leakage, and poor wound healing [8–10]. These adverse events can impair the quality of life, lead to great financial burden, and delay subsequent treatment, which might potentially translate into a reduced life expectancy in patients [11–13]. Given these suboptimal treatment outcomes, we considered the survival benefit of preoperative CCRT as questionable for patients with resectable mid/low rectal cancer.

To confirm the prognostic effect of CCRT, we completed a prospective, randomized phase II trial comparing TME with and without preoperative CCRT, both followed by postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. The short-term results were reported in 2015, and the two groups had similar functional sphincter preservation rates and 3-year survival outcomes [14]. In the absence of a short-term survival benefit, prolongation of follow-up duration was necessary to observe late postoperative recurrences and survival events to obtain a more definite result. Here, we reported the long-term outcomes including local recurrence, distant metastasis, disease-free survival (DFS), and overall survival (OS) from the current trial after a median follow-up of 71 months.

Patients and methods

Patient eligibility, randomization, and treatment

The present study was designed as a prospective, randomized phase II trial (Clinical Trial Number ChiCTR-TRC-08000122) approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (Approval Number: YP2008005). Informed consent was obtained from the patients before initial treatment. The design of this trial has been previously reported [14]. The eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) histologically confirmed rectal adenocarcinoma; (2) inferior tumor margin within 10 cm from the anal verge before CRT; (3) presence of clinical T3-T4 or node-positive resectable tumor; (4) no malignant disease in the anal canal; and (5) no initial evidence of distant metastasis. All patients were required to undergo colonofiberscopy, endorectal ultrasonography (ERUS), computed tomography (CT) scanning of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, and/or abdominopelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before CCRT and surgery to determine the resectibility of rectal tumor. Patients were randomly allocated into the TME and CCRT + TME groups in a ratio of 1:1 using a computer generated scheme, and their identities were concealed in consecutively numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. Patients in the TME group underwent TME followed by 6 cycles of standard XELOX regimen (oxaliplatin at 130 mg/m2 on Day 1 and capecitabine at 1000 mg/m2 twice daily on Days 1–14 with an interval of 7 days) for pathologic stage II–III disease. Patients in the CCRT + TME group underwent preoperative CCRT (oxaliplatin at 100 mg/m2 on Day 1 and capecitabine at 1000 mg/m2 twice daily on Days 1–14 with an interval of 7 days with a concurrent total dose of 50 Gy radiotherapy) followed by TME and subsequently 4 cycles of postoperative standard XELOX adjuvant chemotherapy.

Follow-up

The protocol-specified follow-up was conducted every 3 months for the first 2 years after surgery and every 6 months for the following 3 years. Evaluations consisted of physical examination, complete blood count and blood chemistry analyses, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) measurement, chest radiography, and abdominal ultrasound at each visit. Chest/abdomen/pelvis CT and/or abdominopelvic MRI were performed every 6 months, and colonofiberscopy was performed annually. The final follow-up visit occurred in June 2017.

Endpoint definition

The primary endpoint was DFS. Secondary endpoints included OS and cumulative rates of local recurrence and distant metastasis. Recurrence within the pelvis was defined as local recurrence, and recurrence outside the pelvis was considered as distant metastasis. Both local recurrence and distant metastasis were considered as postoperative recurrence. OS was defined as the interval from tumor resection to the date of death from any cause or the date of last follow-up, whereas DFS was defined as the interval from tumor resection to the date of disease recurrence, death from disease, or last follow-up. Patients without local recurrence, distant metastasis, or death at the last follow-up date were subjected to random censoring.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS statistics software, version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 6.01 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Clinicopathologic parameters were compared between the two treatment groups by using the Chi square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Survival outcomes were estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between groups were assessed with the log-rank test. Variables that were statistically significant with a P < 0.05 in univariate Cox models for DFS and OS were further assessed with multivariate Cox models. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. All statistical tests used in this study were two-sided, and a P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patients, tumor characteristics, and treatment compliance

Figure 1 shows the trial profile. Between March 23, 2008 and August 2, 2012, 192 patients were enrolled from Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, with 95 patients randomized into the TME group and 97 to the CCRT + TME group. Eight patients were considered ineligible after randomization, and the reasons for ineligibility are summarized in Fig. 1. The number of eligible patients was 94 (98.9%) of 95 in the TME group and 90 (92.8%) of 97 in the CCRT + TME group. Chemotherapy compliance and CCRT safety have been previously reported [14]. All patients underwent R0 resection of rectal tumor. The median ages of the TME group and the CCRT + TME group were 58 years (range 29–70 years) and 56 years (range 28–70 years), respectively. The median numbers of perioperative chemotherapy cycles were 6 (range 0–8) for the TME group and 6 (range 2–8) for the CCRT + TME group. The demographic and treatment characteristics of the TME and CCRT + TME groups were comparable except for pathologic T stage (pT) and adjuvant chemotherapy (both P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Trial profile of patient eligibility, randomization, and treatment. TME, total mesorectal excision; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; 3D-RT, 3-dimentional radiotherapy; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic and treatment characteristics of 184 patients with mid/low rectal cancer

| Variable | TME group [cases (%)] | CCRT + TME group [cases (%)] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 94 | 90 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| ≤ 60 | 62 (66.0) | 64 (71.1) | 0.452 |

| > 60 | 32 (34.0) | 26 (28.9) | |

| Sex | 0.273 | ||

| Male | 51 (54.3) | 56 (62.2) | |

| Female | 43 (45.7) | 34 (37.8) | |

| DAV (cm) | 0.290 | ||

| ≤ 5 | 47 (50.0) | 52 (57.8) | |

| > 5 | 47 (50.0) | 38 (42.2) | |

| cTNM stage | 0.097 | ||

| II | 48 (51.1) | 33 (36.7) | |

| III | 46 (48.9) | 57 (63.3) | |

| Type of resection | 0.849 | ||

| LAR | 67 (71.3) | 63 (70.0) | |

| APR | 27 (28.7) | 27 (30.0) | |

| pT stage | < 0.001 | ||

| pT0–2 | 22 (23.4) | 56 (62.2) | |

| pT3–4 | 72 (76.6) | 34 (37.8) | |

| pN stage | 0.005 | ||

| pN0 | 55 (58.5) | 70 (77.8) | |

| pN1–2 | 39 (41.5) | 20 (22.2) | |

| pTNM stage | < 0.001 | ||

| pT0N0M0 | 0 | 32 (35.6) | |

| pT1–2N0M0 | 16 (17.0) | 17 (18.9) | |

| pT3–4N0M0 | 39 (41.5) | 21 (23.3) | |

| pT1–4N1–2M0 | 39 (41.5) | 20 (22.2) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 61 (64.9) | 79 (87.8) | |

| No | 33 (35.1) | 11 (12.2) | |

| Cycles of perioperative chemotherapy | |||

| 1–7 | 52 (55.3) | 56 (62.2) | 0.342 |

| 8 | 42 (44.7) | 34 (37.8) | |

TME, total mesorectal excision; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; DAV, distance of the inferior tumor margin from the anal verge; cTNM stage, clinical tumor-node-metastasis classification; LAR, low anterior resection; APR, abdominoperineal resection; pTNM stage, pathologic tumor-node-metastasis classification; pT stage, pathologic tumor stage; pN stage, pathologic node stage

Follow-up and postoperative events

At the time of analysis, the median follow-up duration was 71 months (range 4–109 months) for all patients, with 76 months (range 10–106 months) for the TME group and 66 months (range 4–109 months) for the CCRT + TME group. The 5-year survival data were obtained for 83 (88.3%) patients in the TME group and for 80 (88.9%) patients in the CCRT + TME group. A total of 37 (20.1%) patients died during follow-up; among them, 21 were in the TME group, and 16 were in the CCRT + TME group, including 35 who died due to rectal cancer progression, 1 due to nasopharyngeal cancer (NPC), and 1 due to other cause. After tumor resection, local recurrence occurred in 9 (4.9%) patients, whereas 29 (15.8%) developed distant metastasis in the whole cohort. Table 2 shows that the postoperative recurrence periods and patterns were comparable across the two treatment groups. The 5-year cumulative local recurrence rates were 6.3% and 5.0% for the CCRT + TME and TME groups, respectively (HR = 1.318, 95% CI = 0.354–4.909, P = 0.681, Fig. 2a). The 5-year cumulative distant metastasis rates were 15.0% and 15.7% for the CCRT + TME and the TME group, respectively (HR = 1.057, 95% CI = 0.509–2.198, P = 0.881, Fig. 2b).

Table 2.

Recurrence after radical resection in the TME and CCRT + TME groups

| Variable | TME group [cases (%)] | CCRT + TME group [cases (%)] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative recurrence | 0.971 | ||

| Yes | 19 (20.2) | 18 (20.0) | |

| No | 75 (79.8) | 72 (80.0) | |

| Recurrence period | 0.858 | ||

| Early recurrence (≤ 24 months) | 10 (52.6) | 10 (55.6) | |

| Late recurrence (> 24 months) | 9 (47.4) | 8 (44.4) | |

| Recurrence patterna | |||

| Local recurrence | 4 (4.3) | 5 (5.6) | 0.743 |

| Liver metastasis | 2 (2.1) | 4 (4.4) | 0.437 |

| Lung metastasis | 9 (9.6) | 7 (7.8) | 0.665 |

| Other site metastasis | 4 (4.3) | 6 (6.7) | 0.530 |

TME, total mesorectal excision; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy

aThere were 3 patients developed multiple metastasis

Fig. 2.

Cumulative rates of local recurrence (a) and distant metastasis (b) in the TME and CCRT + TME groups. TME, total mesorectal excision; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval

Overall and disease-free survival

In the whole cohort, the 5-year DFS and OS rates were 84.8% and 85.1%, respectively. There were no significant differences in the 5-year DFS and OS rates between the CCRT + TME and TME groups (5-year DFS rate: 85.2% vs. 84.3%, P = 0.969, Fig. 3a; 5-year OS rate: 83.5% vs. 86.5%, P = 0.719, Fig. 3b). Univariate analysis revealed that pT3–4 (HR = 2.940, 95% CI = 1.344–6.434, P = 0.007) and pathologic N stage (pN) 1–2 (HR = 2.903, 95% CI = 1.519–5.546, P = 0.001) were significant negative predictors of 5-year DFS rate. In the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model, pN1–2 (HR = 2.281, 95% CI = 1.157–4.495, P = 0.017) was identified as an independent predictor of 5-year DFS rate. For 5-year OS rate, pT3–4 (HR = 2.365, 95% CI = 1.115–5.018, P = 0.025) was the only significant negative predictor (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Disease-free survival (a) and overall survival curves (b) of the TME and CCRT + TME groups. TME, total mesorectal excision; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors for disease-free survival and overall survival in 184 patients with mid/low rectal cancer

| Variable | 5-year DFS rate | 5-year OS rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | ||||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age (> 60 vs. ≤ 60 years) | 0.545 (0.249–1.194) | 0.129 | 0.862 (0.425–1.748) | 0.681 | ||

| Sex (male vs. female) | 0.878 (0.460–1.677) | 0.694 | 0.758 (0.397–1.444) | 0.399 | ||

| DAV (≤ 5 cm vs. > 5 cm) | 0.698 (0.361–1.315) | 0.259 | 0.834 (0.488–1.783) | 0.834 | ||

| pT stage (3–4 vs. 0–2) | 2.940 (1.344–6.434) | 0.007 | 2.242 (0.987–5.093) | 0.054 | 2.365 (1.115–5.018) | 0.025 |

| pN stage (1–2 vs. 0) | 2.903 (1.519–5.546) | 0.001 | 2.281 (1.157–4.495) | 0.017 | 1.801 (0.939–3.453) | 0.076 |

| Type of resection (LAR vs. APR) | 0.983 (0.485–1.989) | 0.961 | 0.693 (0.356–1.348) | 0.280 | ||

| Perioperative chemotherapy cycles (≤ 6 vs. > 6) | 2.124 (0.971–4.646) | 0.059 | 1.381 (0.682–2.798) | 0.370 | ||

| Treatment (CCRT + TME vs. TME) | 1.030 (0.540–1.963) | 0.929 | 0.887 (0.461–1.707) | 0.720 | ||

DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; DAV, distance of the inferior tumor margin from the anal verge; pT stage, pathologic tumor stage; pN stage, pathologic node stage; LAR, low anterior resection; APR, abdominoperineal resection; TME, total mesorectal excision; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy

Italic values indicate significance of p vaule (p < 0.05)

Figure 4 shows a forest plot with HR for 5-year DFS and OS rates in the CCRT + TME group compared with the TME group stratified by sex, age, distance of the inferior tumor margin from the anal verge, pT and pN stages, and type of tumor resection. The results showed that the 5-year DFS and OS rates were comparable between the two groups in all stratification analyses.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of disease-free survival (a) and overall survival (b) of the TME and CCRT + TME groups in stratification analyses. TME, total mesorectal excision; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; CI, confidence interval; LAR, low anterior resection; APR, abdominoperineal resection

Discussion

The current study reveals that after a median follow-up of 69 months, preoperative CCRT followed by TME yields similar 5-year survival outcomes, including DFS, OS, cumulative local recurrence, and distant metastasis, to TME alone. These findings suggest that the widespread application of preoperative CCRT might not achieve expected survival benefits if high-quality TME surgery can be performed.

It is well known that compared with TME alone, preoperative radiotherapy improves local disease control for locally advanced rectal cancer, with a relative risk reduction of greater than 50% for postoperative local recurrence [15, 16]. However, our results showed that the 5-year cumulative rate of local recurrence was only slightly higher in the CCRT + TME group than in the TME group (6.3% vs. 5.0%, P = 0.681). Similarly, Williamson et al. [6] reported that preoperative CRT followed by surgery resulted in a higher 5-year local recurrence rate than did surgery alone for patients with stage II/III mid/low rectal cancer (6.5% vs. 0, P = 0.040). Because high-quality surgery resulted in a local recurrence rate of less than 5%, the significance of benefits from preoperative CCRT were difficult to determine for this selective cohort. Moreover, a trial involving TME conducted by the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG) has noted that the superiority of preoperative radiotherapy on local recurrence reduction was decreased from 70.7% at 2 years to 48.6% at 5 years during follow-up [15, 17]. Even after 12 years of follow-up, the rate of local recurrence was similar to that at 5 years after surgery, with 11% in the surgery-alone group and 9% in the radiotherapy + surgery group [18], indicating that the effect of radiotherapy on local recurrence control may be attenuated with time.

Consistent with our findings, previous clinical trials have demonstrated that distant metastasis rate was 3–6 times higher than the local recurrence rate in locally advanced rectal cancer, and metastasis remains the predominant reason for treatment failure [19–21], probably because of insufficient systemic control of micrometastasis by chemotherapy. To enhance systemic control, we added oxaliplatin to the capecitabine-based (XELOX) regimen for the CCRT + TME group, which has been shown to result in a significant increase in tumor response and to be well tolerated in Chinese locally advanced rectal cancer patients [22–24]. Although the CCRT + TME group achieved a 35.6% pathologic complete response (pCR) rate in our previous analysis [14], this treatment strategy failed to further reduce the distant metastasis rate relative to that in the TME group (3-year: 10.0% vs. 12.8%, P = 0.834; 5-year: 15.0% vs. 15.7%, P = 0.881). To the best of our knowledge, the value of adding oxaliplatin to the preoperative CCRT regimen for controlling distant metastasis remains unconfirmed [25–27]. Therefore, use of oxaliplatin may be debatable for these patients.

Thus far, accumulating evidence after long-term follow-up has revealed that preoperative CCRT had no significant effect on prolonging OS or DFS in patients with resectable rectal cancer [6, 28, 29]. In line with the 3-year survival outcomes of our patients [14], no significant differences were observed for the 5-year DFS and OS rates between the CCRT + TME and TME groups in the present study. It should be emphasized that perioperative chemotherapy with the XELOX regimen was recommended for all patients in the present study. Adjuvant chemotherapy with the XELOX regimen has been demonstrated to improve long-term survival in patients with resectable stage III colon cancer, with a potential effect on eliminating micrometastatic disease [30–32]. In the present study, both groups of patients received a median of 6 cycles of perioperative chemotherapy, and the completion rate of full course of therapy was comparable between the two groups (44.7% vs. 37.8%, P = 0.342). Based on these results, the efficacy of perioperative chemotherapy might outweigh the effect of CCRT on survival outcomes. Therefore, 6–8 cycles of perioperative chemotherapy with the XELOX regimen should be recommended for rectal cancer patients, irrespective of whether they undergo TME alone or in combination with CCRT, to minimize the risk of tumor recurrence.

Tumor pathologic stage has been widely confirmed as a prominent factor affecting survival outcomes in rectal cancer patients [33, 34]. In the present study, pN1–2 and pT3–4 were identified as the most important risk factors for 5-year DFS and OS rates, respectively, indicating that when high-quality surgery could be performed, the prognosis was not determined by preoperative treatment strategy but rather by tumor parameters. We also attempted to identify subgroups of patients with specific tumor features who would benefit from preoperative CCRT. Unfortunately, none of the subgroups of patients displayed significant improvements in 5-year survival outcomes after treatment with preoperative CCRT in the present study. The DCCG TME trial [17, 18] and a Swedish rectal cancer trial [35] have shown that the effects of preoperative radiotherapy were most convincing for patients with TNM stage III, mid/low rectal cancer without circumferential resection margin involvement. Because the high quality of TME and the systemic treatment with chemotherapy are likely to result in noticeable effects on survival, our trial was not able to capture the small but potential meaningful differences between the TME and CCRT + TME groups.

Some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. Because new diagnostic techniques, including MRI and ERUS, were not available at our center between 2008 and 2009, tumor staging was mostly based on CT scan examination, which explains the 62.8% and 41.5% staging accuracy for pT and pN stage, respectively [14]. This limitation might have caused a certain proportion of patients with stage I disease to be overtreated with preoperative CCRT, which might have led to the underestimation of the effect of preoperative CCRT. In addition, the recently identified high-risk parameters for rectal cancer such as threatened mesorectal fascia and extramural venous invasion were not evaluated by high-resolution MRI in the present study. These parameters might help to further optimize preoperative treatment strategies [36, 37]. Moreover, data on the molecular characteristics of tumors were not available for the patients in the present study. It has been shown that the expression of cyclooxygenase-2, vascular endothelial growth factor, and Raf kinase inhibitor protein and the mutational status of KRAS represent valuable molecular markers that can be used for predicting treatment outcomes in rectal cancer patients [38, 39]. Therefore, future studies should include the analysis of tumor molecular biomarkers.

Conclusions

Despite the increase in follow-up durations, there is still no conclusive effect of CCRT on survival outcomes. Our long-term data supported that a selective policy towards preoperative CCRT should be practiced for rectal cancer patients if high-quality TME surgery and aggressive chemotherapy were performed.

Authors’ contributions

FW, WF and JP are responsible for the study concept and design and drafting of the manuscript. ZL and ZP provide technical and material support. LL, YG, HL, GC, XW, PD and ZZ participate in acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. DW supervise the study and give critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all colleagues of Department of Colorectal Surgery in Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center who have been involved with performing the treatment for the present study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets were analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Anyone who is interested in the information should contact wands@sysucc.org.cn. The key raw data have been deposited into the Research Data Deposit (https://www.researchdata.org.cn), with the Approval Number of RDDA2018000756.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was undertaken in accordance with the ethical standards of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consents before initial treatment were requested, and the study approval was obtained from independent ethics committees at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center.

Funding

This study was funded by Sun Yat-sen University Clinical Research 5010 Program (Clinical Trial Number: ChiCTR-TRC-08000122).

Contributor Information

Fulong Wang, Email: wangful@sysucc.org.cn.

Wenhua Fan, Email: fanwh@sysucc.org.cn.

Jianhong Peng, Email: pengjh@sysucc.org.cn.

Zhenhai Lu, Email: luzhh@sysucc.org.cn.

Zhizhong Pan, Email: panzhzh@sysucc.org.cn.

Liren Li, Email: lilr@sysucc.org.cn.

Yuanhong Gao, Email: gaoyh@sysucc.org.cn.

Hui Li, Email: 493401478@qq.com.

Gong Chen, Email: chengong@sysucc.org.cn.

Xiaojun Wu, Email: wuxj@sysucc.org.cn.

Peirong Ding, Email: dingpr@sysucc.org.cn.

Zhifan Zeng, Email: zengzhifan@sysucc.org.cn.

Desen Wan, Phone: +86-20-87343124, Email: wands@sysucc.org.cn.

References

- 1.Glimelius B, Tiret E, Cervantes A, Arnold D. Rectal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(Suppl 6):i81–i88. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson AR, Venook AP, Bekaii-Saab T, Chan E, Chen YJ, Cooper HS, et al. Rectal cancer, version 2.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(6):719–728. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonjer HJ, Deijen CL, Abis GA, Cuesta MA, van der Pas MH, de Lange-de KE, et al. A randomized trial of laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(14):1324–1332. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeong SY, Park JW, Nam BH, Kim S, Kang SB, Lim SB, et al. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid-rectal or low-rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): survival outcomes of an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(7):767–774. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng J, Lin J, Zeng Z, Wu X, Chen G, Li L, et al. Addition of oxaliplatin to capecitabine-based preoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: long-term outcome of a phase II study. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(4):4543–4550. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williamson JS, Jones HG, Davies M, Evans MD, Hatcher O, Beynon J, et al. Outcomes in locally advanced rectal cancer with highly selective preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Br J Surg. 2014;101(10):1290–1298. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodel C, Graeven U, Fietkau R, Hohenberger W, Hothorn T, Arnold D, et al. Oxaliplatin added to fluorouracil-based preoperative chemoradiotherapy and postoperative chemotherapy of locally advanced rectal cancer (the German CAO/ARO/AIO-04 study): final results of the multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):979–989. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00159-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin J, Peng J, Qdaisat A, Li L, Chen G, Lu Z, et al. Severe weight loss during preoperative chemoradiotherapy compromises survival outcome for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(12):2551–2560. doi: 10.1007/s00432-016-2225-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin JZ, Peng JH, Qdaisat A, Lu ZH, Wu XJ, Chen G, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy creates an opportunity to perform sphincter preserving resection for low-lying locally advanced rectal cancer based on an oncologic outcome study. Oncotarget. 2016;7(35):57317–57326. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao YH, Lin JZ, An X, Luo JL, Cai MY, Cai PQ, et al. Neoadjuvant sandwich treatment with oxaliplatin and capecitabine administered prior to, concurrently with, and following radiation therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer: a prospective phase 2 trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90(5):1153–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mongin C, Maggiori L, Agostini J, Ferron M, Panis Y. Does anastomotic leakage impair functional results and quality of life after laparoscopic sphincter-saving total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer? A case-matched study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29(4):459–467. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-1833-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Short MN, Aloia TA, Ho V. The influence of complications on the costs of complex cancer surgery. Cancer Am Cancer Soc. 2014;120(7):1035–1041. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tevis SE, Kohlnhofer BM, Stringfield S, Foley EF, Harms BA, Heise CP, et al. Postoperative complications in patients with rectal cancer are associated with delays in chemotherapy that lead to worse disease-free and overall survival. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56(12):1339–1348. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182a857eb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan WH, Wang FL, Lu ZH, Pan ZZ, Li LR, Gao YH, et al. Surgery with versus without preoperative concurrent chemoradiotherapy for mid/low rectal cancer: an interim analysis of a prospective, randomized trial. Chin J Cancer. 2015;34(9):394–403. doi: 10.1186/s40880-015-0024-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapiteijn E, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, Putter H, Steup WH, Wiggers T, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):638–646. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cedermark B, Dahlberg M, Glimelius B, Pahlman L, Rutqvist LE, Wilking N. Improved survival with preoperative radiotherapy in resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(14):980–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704033361402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peeters KC, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, Kranenbarg EK, Putter H, Wiggers T, et al. The TME trial after a median follow-up of 6 years: increased local control but no survival benefit in irradiated patients with resectable rectal carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2007;246(5):693–701. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000257358.56863.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Gijn W, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, Kranenbarg EM, Putter H, Wiggers T, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer: 12-Year follow-up of the multicentre, randomised controlled TME trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(6):575–582. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu L, Cao C, Zhu Y, Li D, Feng H, Luo J, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin for locally advanced rectal cancer: long-term results of a phase II trial. Med Oncol. 2015;32(3):70. doi: 10.1007/s12032-015-0512-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sauer R, Liersch T, Merkel S, Fietkau R, Hohenberger W, Hess C, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: results of the German CAO/ARO/AIO-94 randomized phase III trial after a median follow-up of 11 years. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(16):1926–1933. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Capirci C, Valentini V, Cionini L, De Paoli A, Rodel C, Glynne-Jones R, et al. Prognostic value of pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer: long-term analysis of 566 ypCR patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72(1):99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao YH, Lin JZ, An X, Luo JL, Cai MY, Cai PQ, et al. Neoadjuvant sandwich treatment with oxaliplatin and capecitabine administered prior to, concurrently with, and following radiation therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer: a prospective phase 2 trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90(5):1153–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao YH, An X, Sun WJ, Cai J, Cai MY, Kong LH, et al. Evaluation of capecitabine and oxaliplatin administered prior to and then concomitant to radiotherapy in high risk locally advanced rectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109(5):478–482. doi: 10.1002/jso.23516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin JZ, Zeng ZF, Wu XJ, Wan DS, Chen G, Li LR, et al. Phase II study of pre-operative radiotherapy with capecitabine and oxaliplatin for rectal cancer and carcinoembryonic antigen as a predictor of pathological tumour response. J Int Med Res. 2010;38(2):645–654. doi: 10.1177/147323001003800227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodel C, Graeven U, Fietkau R, Hohenberger W, Hothorn T, Arnold D, et al. Oxaliplatin added to fluorouracil-based preoperative chemoradiotherapy and postoperative chemotherapy of locally advanced rectal cancer (the German CAO/ARO/AIO-04 study): final results of the multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):979–989. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00159-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerard JP, Azria D, Gourgou-Bourgade S, Martel-Lafay I, Hennequin C, Etienne PL, et al. Clinical outcome of the ACCORD 12/0405 PRODIGE 2 randomized trial in rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(36):4558–4565. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.8771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allegra CJ, Yothers G, O’Connell MJ, Beart RW, Wozniak TF, Pitot HC, et al. Neoadjuvant 5-FU or capecitabine plus radiation with or without oxaliplatin in rectal cancer patients: a phase III randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(11):djv248. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bosset JF, Collette L, Calais G, Mineur L, Maingon P, Radosevic-Jelic L, et al. Chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(11):1114–1123. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song JH, Jeong JU, Lee JH, Kim SH, Cho HM, Um JW, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for stage II–III resectable rectal cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Radiat Oncol J. 2017;35(3):198–207. doi: 10.3857/roj.2017.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmoll HJ, Tabernero J, Maroun J, de Braud F, Price T, Van Cutsem E, et al. Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil/folinic acid as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer: final results of the NO16968 randomized controlled phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(32):3733–3740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.9107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haller DG, Tabernero J, Maroun J, de Braud F, Price T, Van Cutsem E, et al. Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil and folinic acid as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(11):1465–1471. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.6297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmoll HJ, Twelves C, Sun W, O’Connell MJ, Cartwright T, McKenna E, et al. Effect of adjuvant capecitabine or fluorouracil, with or without oxaliplatin, on survival outcomes in stage III colon cancer and the effect of oxaliplatin on post-relapse survival: a pooled analysis of individual patient data from four randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(13):1481–1492. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70486-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valentini V, van Stiphout RG, Lammering G, Gambacorta MA, Barba MC, Bebenek M, et al. Nomograms for predicting local recurrence, distant metastases, and overall survival for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer on the basis of European randomized clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(23):3163–3172. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunderson LL, Jessup JM, Sargent DJ, Greene FL, Stewart A. Revised tumor and node categorization for rectal cancer based on surveillance, epidemiology, and end results and rectal pooled analysis outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):256–263. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Folkesson J, Birgisson H, Pahlman L, Cedermark B, Glimelius B, Gunnarsson U. Swedish rectal cancer trial: long lasting benefits from radiotherapy on survival and local recurrence rate. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5644–5650. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Son IT, Kim YH, Lee KH, Kang SI, Kim DW, Shin E, et al. Oncologic relevance of magnetic resonance imaging-detected threatened mesorectal fascia for patients with mid or low rectal cancer: a longitudinal analysis before and after long-course, concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Surgery. 2017;162(1):152–163. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chand M, Evans J, Swift RI, Tekkis PP, West NP, Stamp G, et al. The prognostic significance of postchemoradiotherapy high-resolution MRI and histopathology detected extramural venous invasion in rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2015;261(3):473–479. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim JW, Kim YB, Choi JJ, Koom WS, Kim H, Kim NK, et al. Molecular markers predict distant metastases after adjuvant chemoradiation for rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84(5):e577–e584. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.07.2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng J, Lin J, Qiu M, Zhao Y, Deng Y, Shao J, et al. Oncogene mutation profile predicts tumor regression and survival in locally advanced rectal cancer patients treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy and radical surgery. Tumour Biol. 2017;39(7):1393380026. doi: 10.1177/1010428317709638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets were analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Anyone who is interested in the information should contact wands@sysucc.org.cn. The key raw data have been deposited into the Research Data Deposit (https://www.researchdata.org.cn), with the Approval Number of RDDA2018000756.