Living donor kidney transplantation is the best available treatment option for ESKD. Transplantation generally provides better length and quality of life than dialysis, and living donor transplantation offers superior graft and patient survival compared with deceased donor kidney transplantation. It is unavoidable that some clinical subgroups will experience better post-transplant outcomes than others (for example, patients with polycystic kidney disease compared with those with diabetic kidney failure). However, disparities may be defined as differences that are unnecessary and modifiable (1). Racial disparities in access to all forms of kidney transplantation have long been recognized as a critical concern, because reduced access impairs outcomes. Importantly, a recent study by Purnell et al. (2) shows that, even with this recognition, racial disparities in living donor transplantation have increased over time. Using national registry data for >453,000 adult kidney transplant candidates, the 2-year cumulative incidence rates of living donor transplantation in 2014 versus 1995 by race and ethnicity were 11.4% versus 7.0%, respectively, for whites; 2.9% versus 3.4%, respectively, for blacks; 5.9% versus 6.8%, respectively, for Hispanics; and 5.6% versus 5.1%, respectively, for Asians. These lower living donor transplant rates in nonwhites were also found when including preemptive recipients who were not waitlisted. After multivariable adjustment, the relative likelihood of living donor transplantation in black versus white candidates declined from 65% lower access in 1995–1999 (subhazard ratio, 0.45; 95% confidence interval, 0.42 to 0.48) to 73% lower access in 2010–2014 (subhazard ratio, 0.27; 95% confidence interval, 0.26 to 0.28).

As clinicians and researchers dedicated to the safe advancement of opportunities for living donor transplantation, we applaud the efforts to quantify and highlight growing national disparities by Purnell et al. (2) as a “call to action.” Multiple barriers to living donor transplantation exist, including inadequate education and outreach; uncompensated costs to donors; and ongoing needs to advance donor safety, risk assessment, and follow-up to sustain public trust. These barriers are exacerbated by disparities in income, education, and health care access. However, achieving solutions is far from simple, because the full story of disparities spans all phases of care, including specialty access, transplant education, referral and access to transplantation, and organ donation patterns.

Living donors are drawn from the community and patients’ social networks, and consideration of living donor transplant access should also be framed in terms of donation rates in the base population. A population-based analysis that accounted for race-related differences in ESKD and income found that blacks have higher rates of living donation per million compared with whites (3). Using a base population perspective drawn from integrated US Census and transplant registry data, Gill et al. (4) recently reported disparities in living donation rates on the basis of sex and income, whereas donation by race was equivalent. These findings suggest that part of the access disparity among black patients with kidney disease derives from higher disease burden and need, rather than lower donation rates in the community per se. Importantly, compared with white recipients of living donor transplants, black patients more commonly receive kidneys from black living donors, and their potential living donors are more likely to be excluded from donation because of medical conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes. Another way to frame the scope of the problem is that, in the period from 2004 to 2013, 21% of kidney transplants in black recipients were from living donors, whereas 46% of kidney transplants in whites were from living donors (1). Collectively, these findings suggest that black transplant candidates may need to reach out to more potential donors to ultimately identify a healthy, willing living donor for whom both medical and financial risks of donation are acceptable. Medical evaluation and selection practices should prioritize donor health over recipient access, but black donor candidates should not all be excluded on the basis of their race alone. It is possible that new tools, such as genetic screening of black living donor candidates for APOL1 risk variants, could further improve the risk stratification of this population (5). These efforts must continue, because state of the art risk assessment and transparent disclosure are all vital to advancing living donation within a defensible system of practice (6). However, in this context, efforts to reduce modifiable barriers to donation are even more critical.

Educational barriers to the pursuit of potential living donors, driven by inadequate knowledge of benefits, risks, and opportunities for the procedure, are particularly salient as a modifiable target for improving access and reducing disparities. The 2017 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes “KDIGO clinical practice guideline on the evaluation and care of living kidney donors” recommends efforts to improve public awareness of opportunities for living donation (6), although the optimal design of awareness campaigns warrants increased study. Notably, a recent study reported that many online resources about donation and transplantation are too complex for the health literacy of those in need of this information (7). To help address the need for education tailored to the literacy and backgrounds of patients with kidney failure, the United Network for Organ Sharing Living Donor Committee reviewed the state of current evidence on strategies to increase knowledge, communication, and access to living donor kidney transplantation as reported in peer-reviewed medical literature (8), and they prepared a new brochure with health literacy and subject matter review as well as strict attention to reading level (9). In parallel, the committee developed downloadable resources explaining what living donors need to know (9). Other initiatives include the recent launch of online “Live Donor Toolkits” for patients and providers by the American Society of Transplantation and the development of tools to educate patients about the clinical effect of living donor kidney transplantation compared with other treatment options.

Financial barriers to living donation are a long-standing problem, and it has been documented that donors incur many types of direct and indirect costs in the donation process, including those from travel, medications, lost time from work, and dependent care (10). Clinical trials of mechanisms to replace wages lost in the donation process are underway. The National Organ Transplant Act has been clarified to be explicit that “reasonable payments associated with … the expenses of travel, housing, and lost wages incurred by the donor” are legal. The Health Resources and Services Administration established the National Donor Assistance Act to provide travel and lodging support, which is a start, but the grant must be the payer of last resort; additionally, both the donor and the recipient must meet strict income criteria. Policy reforms can help. The Living Donor Protection Act was first introduced in 2014 to prohibit insurance discrimination for donors and protect the right to use the Family and Medical Leave Act to recover after donation surgery. The bill was reintroduced in Congress in March 2017, and although no further action has been taken, we believe that it is an important bill to support.

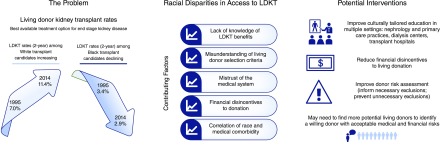

To reinforce and expand the call of Purnell et al. (2) for national strategies to address living donor kidney transplantation barriers, we advocate for (1) broader, repeated living donor kidney transplantation education beginning in the earlier stages of kidney disease and involving patients’ social networks; (2) removal of financial disincentives to donation; and (3) ongoing efforts to strengthen the processes of donor evaluation, selection, and follow-up (Figure 1). In light of growing disparities, robust national efforts from researchers, educators, nephrology providers, and policy makers are urgently needed to support opportunities for healthy, willing persons to share the gift of life, regardless of race and socioeconomic status.

Figure 1.

Addressing a “call to action” may help address racial disparities in access to living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT).

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Amit X. Garg and Dr. James Rodrigue for insights in framing key strategies to resolve disparities in access to living donor kidney transplantation and review of the perspective. Heather Hunt prepared the original infographic for this article and grants permission for its use. Ms. Hunt is president of LIVE ON Organ Donation, Inc., a nonprofit organization that raises money to support living organ donors’ nonmedical expenses, and she is the incoming vice chair of the United Network for Organ Sharing Living Donor Committee.

K.L.L. receives support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases for the study of “Long-Term Health Outcomes after Live Kidney Donation in African Americans” through grant R01DK096008. D.M. receives unrestricted research funding from the Virginia Lee Cook Foundation.

The content of this article does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology (CJASN). Responsibility for the information and views expressed therein lies entirely with the author(s).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Rodrigue JR, Kazley AS, Mandelbrot DA, Hays R, LaPointe Rudow D, Baliga P; American Society of Transplantation: Living donor kidney transplantation: Overcoming disparities in live kidney donation in the US--recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1687–1695, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Purnell TS, Luo X, Cooper LA, Massie AB, Kucirka LM, Henderson ML, Gordon EJ, Crews DC, Boulware LE, Segev DL: Association of race and ethnicity with live donor kidney transplantation in the United States from 1995 to 2014. JAMA 319: 49–61, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill J, Dong J, Rose C, Johnston O, Landsberg D. The effect of race and income on living kidney donation in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol; 24: 1872–1879, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill J, Joffres Y, Rose C, Lesage J, Landsberg D, Kadatz M, Gill J: The change in living kidney donation in women and men in the United States (2005-2015): A population-based analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 1301–1308, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lentine KL, Kasiske BL, Levey AS, Adams PL, Alberú J, Bakr MA, Gallon L, Garvey CA, Guleria S, Li PK, Segev DL, Taler SJ, Tanabe K, Wright L, Zeier MG, Cheung M, Garg AX: KDIGO clinical practice guideline on the evaluation and care of living kidney donors. Transplantation 101[8S Suppl 1]: S1–S109, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lentine KL, Mandelbrot D: Moving from Intuition to Data: Building the Evidence to Support and Increase Living Donor Kidney Transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1383–1385, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou EP, Kiwanuka E, Morrissey PE: Online patient resources for deceased donor and live donor kidney recipients: A comparative analysis of readability. Clin Kidney J 11: 559–563, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunt HF, Rodrigue JR, Dew MA, Schaffer RL, Henderson ML, Bloom R, Kacani P, Shim P, Bolton L, Sanchez W, Lentine KL: Strategies for increasing knowledge, communication and access to living donor transplantation: An evidence review to inform patient education. Curr Transplant Rep 8: 27–44, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN)/United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS): Living Donation: Information for Patients, 2018. Available at: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/resources/living-donation. Accessed April 29, 2018

- 10.Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Morrissey P, Whiting J, Vella J, Kayler LK, Katz D, Jones J, Kaplan B, Fleishman A, Pavlakis M, Mandelbrot DA; KDOC Study Group: Direct and indirect costs following living kidney donation: Findings from the KDOC study. Am J Transplant 16: 869–876, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]