Summary

Complete activation of B cells relies on their capacity to extract tethered antigens from immune synapses by either exerting mechanical forces or promoting their proteolytic degradation through lysosome secretion. Whether antigen extraction can also be tuned by local cues originating from the lymphoid microenvironment has not been investigated. We here show that the expression of Galectin-8—a glycan-binding protein found in the extracellular milieu, which regulates interactions between cells and matrix proteins—is increased within lymph nodes under inflammatory conditions where it enhances B cell arrest phases upon antigen recognition in vivo and promotes synapse formation during BCR recognition of immobilized antigens. Galectin-8 triggers a faster recruitment and secretion of lysosomes toward the B cell-antigen contact site, resulting in efficient extraction of immobilized antigens through a proteolytic mechanism. Thus, extracellular cues can determine how B cells sense and extract tethered antigens and thereby tune B cell responses in vivo.

Keywords: B lymphocytes, immune synapse, Galectin-8, antigen extraction, processing and presentation, cell polarity, mouse immunization

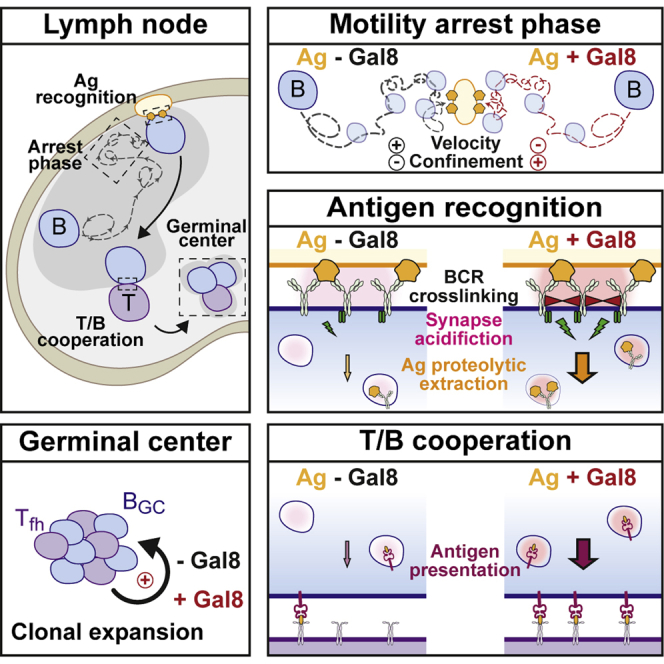

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Galectin-8 reinforces B cell arrest phases upon antigen recognition in vivo

-

•

Galectin-8 sustains BCR signaling during recognition of immobilized antigens

-

•

This enhances lysosome secretion and favors the proteolytic extraction of antigens

-

•

Galectin-8 improves the capacity of B cells to present antigens to helper T cells

Obino et al. report that Galectin-8 interacts with the BCR, promotes B cell arrest phases during surface-tethered antigen encounter, and facilitates synapse formation and lysosome secretion, which favors the proteolytic extraction of antigens. Consequently, Galectin-8 increases the capacity of B cells to present antigens to helper T cells in vivo.

Introduction

The onset of the adaptive immune response requires the activation of B lymphocytes. This process takes place within lymph nodes and is initiated by the engagement of the B cell receptor (BCR) with antigens tethered at the surface of neighboring cell (Carrasco and Batista, 2007, Junt et al., 2007). This cell-cell contact leads to the formation of an immune synapse where surface-tethered antigens are extracted for further processing and presentation onto major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) molecules at the B cell surface. The B cell synapse is characterized by a central cluster of BCR-antigen complexes surrounded by a ring of integrins that include LFA-1 and VLA-4 (Carrasco and Batista, 2006a, Carrasco et al., 2004). Although synapses can form in the absence of adhesion molecules, the interaction of B cell integrins with ICAM-1 or VCAM enhances contact formation when the avidity for the antigen is low (Carrasco and Batista, 2006b, Carrasco et al., 2004). Thus, the context in which membrane-bound antigens are recognized plays an important role in modulating B cell activation and thus the outcome of B cell responses.

Two non-exclusive mechanisms have been implicated in antigen extraction by B cells. The first one involves the local secretion of lysosomes at the synaptic membrane that release proteases and acidify the synaptic cleft, allowing antigen extraction (Obino et al., 2017, Yuseff et al., 2011). This process relies on the polarization of the B cell microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) together with MHC-II+/Lamp-1+ lysosomes toward the BCR-antigen interface (Batista et al., 2001, Obino and Lennon-Duménil, 2014, Yuseff et al., 2011). The second one depends on Myosin IIA-mediated pulling forces that trigger invagination of antigen-containing membranes, which are then internalized into clathrin-coated pits (Fleire et al., 2006, Natkanski et al., 2013, Spillane and Tolar, 2017). Interestingly, the mode of antigen extraction used by B cells depends on the physical properties of their environment: antigens presented on flexible surfaces are mechanically internalized, whereas antigens presented on rigid surfaces are taken up through hydrolase secretion. How environmental cues imposed by extracellular matrix (ECM) and ECM-associated proteins regulate antigen extraction remains, however, to be established.

Among the extracellular proteins susceptible of modulating B cell responses to antigens are the proteins from the Galectin family (Rabinovich and Croci, 2012, Rabinovich and Toscano, 2009). They are evolutionarily conserved glycan-binding proteins that, upon secretion, cross-link cell surface glycosylated proteins in the extracellular space (Elola et al., 2015, Kaltner and Gabius, 2012). This property enables them to modulate adhesive interactions between cells and the ECM (Yamamoto et al., 2008), thereby impacting a wide range of processes such as cell growth, apoptosis, and migration (Eshkar Sebban et al., 2007, Hsieh et al., 2008, Lau et al., 2007). Galectins are expressed by most cells of the immune system and are frequently induced upon inflammation (Rabinovich and Toscano, 2009). The production of Galectin-1 and -8 is significantly upregulated by activated T and B cells, macrophages, and natural killer (NK) cells, and both Galectins have redundant roles in promoting plasma cell formation (Rabinovich and Croci, 2012, Tsai et al., 2011). In addition, Galectin-8 has been implicated in autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and multiple sclerosis where function-blocking autoantibodies against Galectin-8 are frequently detected (Eshkar Sebban et al., 2007, Massardo et al., 2009, Pardo et al., 2017). These observations suggest that Galectin-8 is a good candidate for the modulation of B cell activation in tissues.

We here show that Galectin-8 is expressed at the sub-capsular sinus where B cells recognize surface-tethered antigens and that it enhances B cell responses in vivo. This effect results from the ability of extracellular Galectin-8 to (1) reinforce B cell arrest phases upon antigen recognition in vivo, (2) promote synapse formation during BCR recognition of tethered antigens by triggering a faster recruitment and secretion of lysosomes toward the B cell-antigen contact site, and (3) strengthen B cell activation by enhancing BCR downstream signaling through the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway. These results highlight a key role for Galectin-8 in modulating B cell responses and provide insights on how extracellular cues can tune the ability of B cells to respond to surface-tethered antigens in vivo.

Results

Galectin-8 Is Highly Expressed in the Sub-capsular Sinus of Lymph Nodes

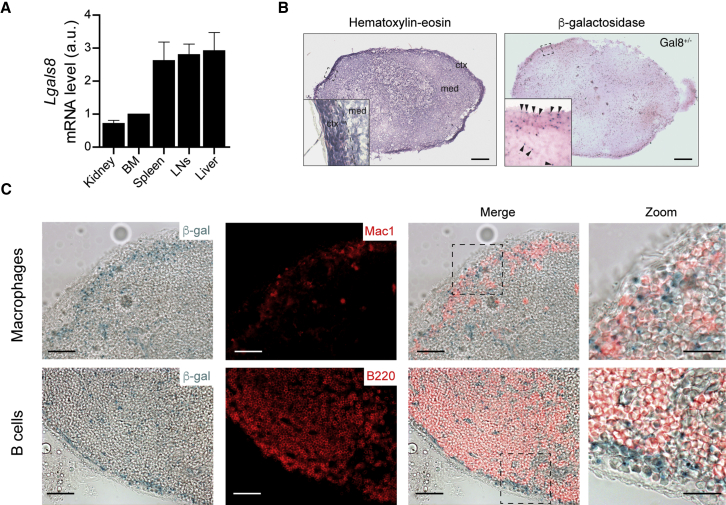

We analyzed the distribution of Galectin-8 in lymphoid tissues. Lgals8 mRNA was found in mouse bone marrow, spleen, and lymph nodes at steady state (Figure 1A), consistent with a previous report (Tribulatti et al., 2009). Additionally, we observed that, within lymph nodes, Galectin-8 was highly expressed at the level of the sub-capsular sinus (SCS) (Figure 1B). Remarkably, Lgals8 mRNA levels were upregulated in lymph nodes from mice with systemic exposure to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Figure S1A). Under these conditions, expression of Galectin-8, detected by β-galactosidase activity under the promoter of the Lgals8 gene, displayed a more diffused expression pattern at the cortex of lymph nodes and particularly within the paracortical area where T cells reside (Figure S1B). However, under steady-state conditions, co-localization studies showed that, at the level of the SCS, Galectin-8 was highly expressed where both B cells and SCS CD169+ macrophages sit (Figure 1C). SCS macrophages have been described as retaining particulate antigens at their surface for presentation to follicular B cells (Carrasco and Batista, 2007, Junt et al., 2007). Of note, while no association between Galectin-8 localization and T cells was observed in the lymph node medulla, Galectin-8 was intensely expressed within the vasculature (Figure S1C). These results highlight that Galectin-8 is expressed within the lymph node regions where B cells acquire and process cell-surface tethered antigens.

Figure 1.

Galectin-8 Is Expressed in Lymphoid Tissues

(A) qRT-PCR analysis of Galectin-8 (Lgals8) mRNA levels in kidney, bone marrow (BM), spleen, lymph nodes (LNs), and liver of C56BL/6 WT mice. Values were normalized with respect to the BM condition for each mouse. n = 5 mice pooled from N = 3 independent experiments. Bar graphs indicate mean ± SEM.

(B) Representative images of H&E staining (left) and β-galactosidase staining (right) of LN cryosection from heterozygous mouse bearing a LacZ expression cassette on one allele of the Lgals8 locus. Arrowheads on the inset highlight β-galactosidase staining within the SCS area. Scale bar, 150 μm.

(C) Representative images of serial lymph node cryosections stained for β-galactosidase (Galectin-8) and macrophages (Mac1) or B cells (B220). Scale bar, 200 μm. Zooms highlight the spatial localization of Galectin-8 together with macrophages and B cells at the SCS. Scale bar, 30 μm.

See also Figure S1.

Galectin-8 Enhances the Arrest Phases of B Cells In Vivo

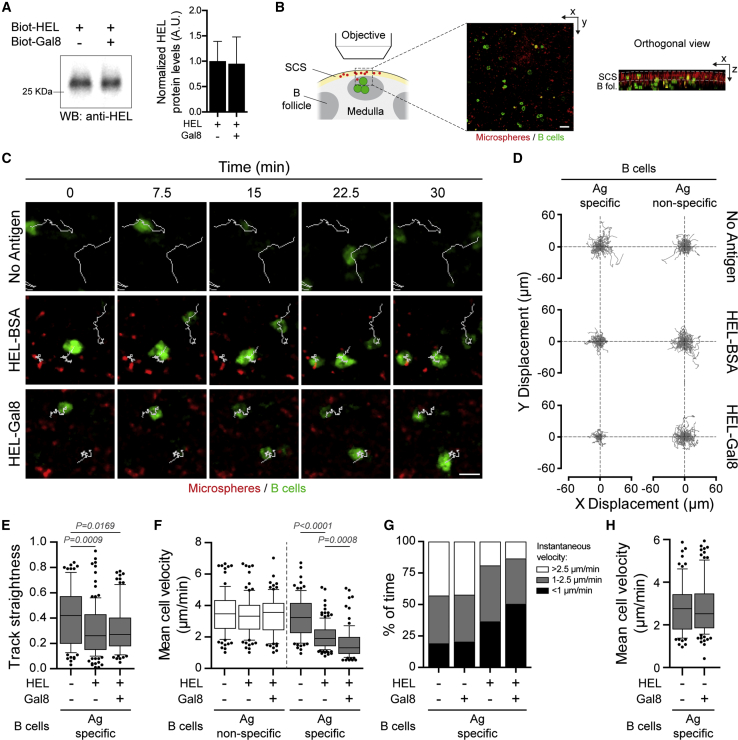

We thus investigated whether addition of extracellular Galectin-8 modulates the capacity of B lymphocytes to extract antigens tethered at the surface of SCS macrophages. We preferred this strategy to knocking out Galectin-8 gene as this c-type lectin was shown to have a redundant role with another member of the Galectin family, Galectin-1, upon plasma cell differentiation (Tsai et al., 2011). Thus, defects associated to Galectin-8 deficiency should most likely be compensated by Galectin-1 in vivo. To address the role of Galectin-8 in antigen extraction by B cells, we adoptively transferred HEL-specific spleen B cells from MD4 transgenic mice (Goodnow et al., 1988) expressing fluorescent MHC-II molecules (MHC-II-GFP) (Boes et al., 2002) into wild-type (WT) (C57BL/6) recipients, which were then immunized 16 hr later by footpad injection of fluorescent microspheres coated with HEL plus Galectin-8 or BSA as control (coated with equal antigen amounts; Figure 2A). Antigen-coated beads were deposited at the surface of SCS macrophages as previously reported (Carrasco and Batista, 2007), and no difference in their distribution was observed between the various experimental conditions (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Galectin-8 Promotes B Cell Arrest Phases In Vivo

(A) Representative western blot and quantification of the amounts of antigen (HEL) effectively immobilized at the surface of 0.2-μm microspheres in the presence of Galectin-8 or not. Data are pooled from N = 3 independent experiments. Bar graphs indicate mean ± SEM.

(B) Schematic and representative image of the observed area within draining popliteal lymph nodes (pLN). Scale bar, 20 μm. The orthogonal view shows the deposit of microspheres at the periphery of pLN.

(C) Representative images of HEL-specific migrating B cells (green) within the sub-capsular area of lymph nodes upon immunization with indicated microspheres (red). Scale bar, 8 μm.

(D) Relative tracks of HEL-specific (MD4) and non-specific (WT) B cells.

(E) Track straightness of B cells shown in (C). Boxes extend from the 25th to 75th percentile, with a line at the median and whiskers extend from the 10th to the 90th percentile.

(F) Mean cell velocity of HEL-specific (gray) and non-specific (white) B cells upon immunization with indicated microspheres. Boxes extend from the 25th to 75th percentile, with a line at the median and whiskers extend from the 10th to the 90th percentile.

(G) Quantification of the percentage of time cells spent at high (>2.5 μm/min; white), intermediate (between 1 and 2 μm/min; gray), and very slow (<1 μm/min; black) speed.

(H) Mean cell velocity of HEL-specific B cells upon immunization with microspheres coated with non-relevant antigen (BSA) in combination or not with Galectin-8. Boxes extend from the 25th to 75th percentile, with a line at the median and whiskers extend from the 10th to the 90th percentile.

In (D)–(H), n > 80 cells from 4 mice per condition pooled from N = 4 independent experiments. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess statistical significance. See also Video S1.

Intra-vital imaging of the draining popliteal lymph node was performed 30 min post-immunization. Tracking of HEL-specific B cells (green, MHC-II-GFP) present within the upper part of the draining lymph node (Figure 2B; Video S1) showed that they displayed shorter and more confined trajectories upon HEL-BSA exposure than naive (no antigen) and antigen non-specific B cells (Figures 2C–2E). In addition, HEL-specific B cells showed reduced mean cell velocity after antigen administration (Figure 2F) and the percentage of time they spent at low speed (<1 μm/min) increased (Figure 2G; 19% for naive B cells versus 37% for HEL-BSA-stimulated B cells). These results are consistent with previous reports highlighting that antigen recognition triggers an arrest phase in B cell migration, thereby allowing the acquisition of cell-surface tethered antigens (Carrasco and Batista, 2007, Junt et al., 2007). Strikingly, track length and mean B cell velocity were even more drastically reduced when antigen was administered together with Galectin-8 (Figures 2C–2F). Accordingly, in this condition, B cells remained at low speed for prolonged periods when compared to B cells exposed to HEL-BSA (Figure 2G; 37% for HEL-BSA versus 51% for HEL-Galectin-8 [Gal8). Importantly, in the absence of BCR engagement with specific antigens, Galectin-8 had no effect on the migratory behavior of B cells (Figures 2F–2H). These data strongly suggest that extracellular Galectin-8 enhances the arrest phase during which B cells extract antigens in vivo.

Time-lapse movie of HEL-specific B cells (green) migrating within the sub-capsular area of lymph nodes at (left, No Antigen) steady state and upon immunization with HEL-BSA- or HEL-Gal8-coated microspheres (middle and right, respectively, red). Scale bar, 20 μm. Time in minutes (mm:ss).

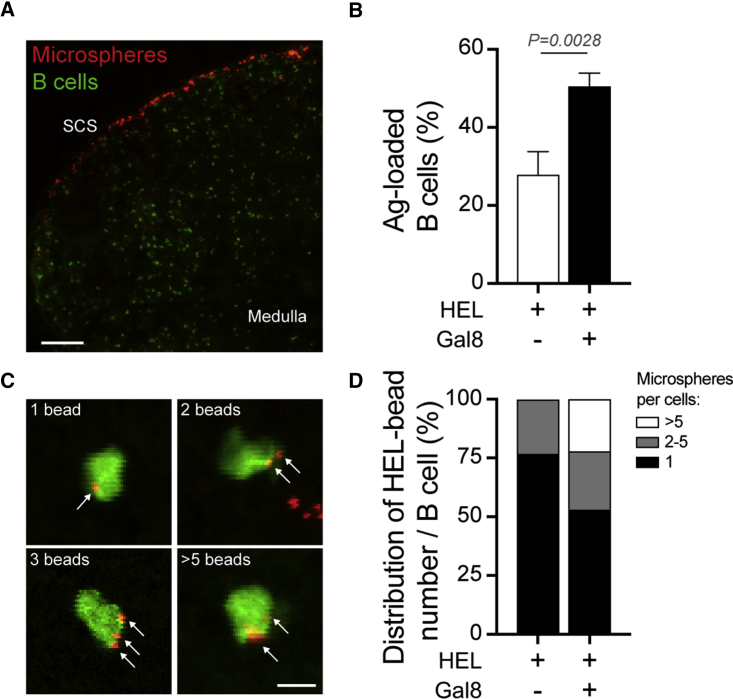

Galectin-8 Enhances Particulate-Antigen Acquisition by B Cells In Vivo

We next assessed whether the enhanced arrest phase observed in B cells upon exposure to antigens plus extracellular Galectin-8 translated into an increased capacity to acquire particulate antigens in vivo. To this end, as described above, carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled HEL-specific spleen B cells were adoptively transferred into WT recipient mice, and 24 hr later, recipient mice were immunized by footpad injection of HEL ± Galectin-8-coated microspheres. We then monitored the percentage of HEL-specific B cells (green) loaded with particulate antigens (red) at 16 hr post-immunization by imaging popliteal lymph node cryosections (Figure 3A). In agreement with the data presented above, exposure of HEL-specific B cells to HEL-Galectin-8 increased their capacity to internalize particulate antigens when compared to HEL-specific B cells exposed to HEL-BSA microspheres (Figure 3B). We next determined the number of antigen-loaded microspheres associated with individual HEL-specific B cells (Figure 3C). While the proportion of HEL-specific B cells loaded with only one microsphere decreased when exposed to HEL-Galectin-8 (77%) compared to HEL-BSA (53%), the proportion of cells that accumulated more than five microspheres greatly increased (0% versus 22%, respectively; Figure 3D). Altogether, these results strongly support a role for extracellular Galectin-8 in favoring particulate antigen acquisition by antigen-specific B cells by enhancing their arrest phase in vivo.

Figure 3.

Galectin-8 Promotes Particulate-Antigen Acquisition In Vivo

(A) Representative image of popliteal lymph node cryosection from recipient mice, showing the distribution of HEL-coated (in absence of Galectin-8) microspheres (red) within the sub-capsular area and adoptively transferred Ag-specific B cells (green). Scale bar, 150 μm.

(B) Quantification of the percentage of HEL-specific B cells loaded with HEL-coated microspheres in combination or not with Galectin-8. n > 100 cells pooled from N = 2 mice per condition. Unpaired t test was used to assess statistical significance. Bar graphs indicate mean ± SEM.

(C) Representative images showing the internalization and accumulation of Ag-coated microspheres within Ag-specific B cells. Scale bar, 8 μm.

(D) Distribution of the number of Ag-coated microspheres per B cells analyzed in (B).

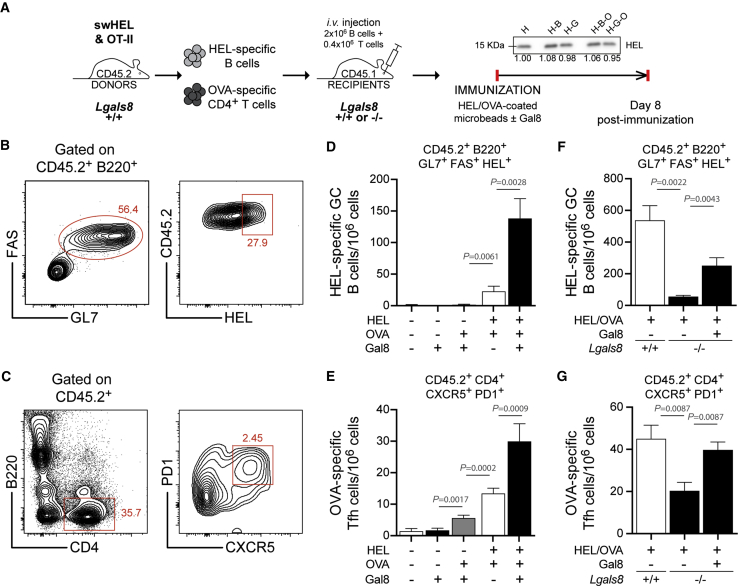

Galectin-8 Stimulates T-B Cooperation In Vivo

We then questioned the physiological relevance of these findings by investigating whether extracellular Galectin-8 promotes B cell dependent activation of CD4+ T lymphocytes in vivo. Antigen presentation to CD4+ T lymphocytes induces the formation of germinal centers (GCs) characterized by the emergence of GC B cells (B220+GL7+FAS+) and follicular helper T cells (Tfh) (CD4+CXCR5+PD-1+) (De Silva and Klein, 2015). For this reason, adoptive cell transfer experiments (donors: HEL-specific B cells from SWHEL transgenic mice [Phan et al., 2003] and ovalbumin [OVA]-specific CD4+ T cells from OT-II transgenic mice, both CD45.2; recipients: C57BL/6, CD45.1) were performed to monitor the generation of GC B and Tfh cells 8 days post-immunization (Figure 4A). We found that the presence of extracellular Galectin-8 enhanced the presentation of immobilized antigens as revealed by the higher numbers of both GC B and Tfh cells found in mice immunized with HEL/OVA plus Galectin-8 compared to mice immunized with only HEL/OVA (Figures 4B–4E). Importantly, equal amounts of HEL were immobilized at the surface of beads under the different conditions used (Figure 4A), and as previously observed, in absence of specific BCR ligand, Galectin-8 was not able to induce the generation of GC B and Tfh cells (Figures 4D and 4E). Importantly, mouse immunization with OVA/Galectin-8 only—i.e., in absence of the B cell antigen HEL—no GC B cells and few Tfh cells were detected (Figures 4D and 4E), supporting a role for extracellular Galectin-8 directly on B cells rather than T cells.

Figure 4.

Exogenous Galectin-8 Favors T-B Cooperation In Vivo

(A) Schematic of the experimental approach used to assess the ability of B cells to present antigen to CD4+ T cells in vivo. The western blot shows the amounts of antigen (HEL) effectively immobilized at the surface of 0.2-μm microspheres in the different conditions used to immunize mice. H, HEL alone; H-B, HEL-BSA; H-G, HEL-Galectin-8; H-B-O, HEL-BSA-OVA; H-G-O, HEL-Galectin-8-OVA. Numbers below the blot represent the normalized density of the bands with respect to the HEL alone condition. Data are representative of N = 3 independent experiments.

(B and C) Representative dot plots used for the gating of (B) HEL-specific GC B cells (CD45.2+B220+HEL+GL7+FAS+) and (C) OVA-specific OT-II Tfh cells (CD45.2+CD4+CXCR5+PD1+).

(D and E) Quantification of the number of (D) HEL-specific GC B cells and (E) OVA-specific OT-II Tfh cells following mouse immunization with indicated microspheres. n = 10 mice per condition pooled from N = 3 independent experiments.

(F and G) Quantification of the number of (F) HEL-specific GC B cells and (G) OVA-specific OT-II Tfh cells in CD45.1 Lgals8+/+ or Lgals8−/− recipient mice (adoptively transferred with CD45.2 Lgals8+/+ SWHEL B cells and OT-II CD4+ T cells) following their immunization with indicated microspheres. n = 6 mice per condition pooled from N = 2 independent experiments. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess statistical significance. All bar graphs indicate mean ± SEM.

However, because these experiments were conducted in WT recipient mice expressing endogenous Galectin-8, we could not formally show that extracellular exogenous Galectin-8 was solely responsible for the enhanced antigen presentation capacity observed in vivo. To address this issue, we repeated the mouse immunization experiments described above using Lgals8−/− recipient mice (Figure 4A). Under these conditions, Galectin-8 expression was abolished in recipient mice, which therefore allowed us to determine the specific contribution of extracellular Galectin-8 in tuning B cell antigen presentation capacity. Strikingly, immunization of Lgals8−/− recipient mice with HEL/OVA led to an impaired generation of GC B and Tfh cells when compared to Lgals8+/+ control counterparts (Figures 4F and 4G), strongly arguing for a role of extracellular Galectin-8 in enhancing antigen presentation by B cells. Importantly, immunization of these mice with HEL/OVA plus exogenous Galectin-8 partially rescued the antigen presentation capacity of HEL-specific B cells as revealed by the numbers of GC B and Tfh cells (Figures 4F and 4G). Hence, extracellular Galectin-8 enhances the capacity of antigen-specific B cells to extract and present immobilized antigens to CD4+ T cells and enter the GC reaction in vivo.

Galectin-8 Favors Immobilized-Antigen Extraction and Presentation In Vitro

We next searched for a mechanism by which Galectin-8 promotes antigen extraction by B cells. We first confirmed the effect of Galectin-8 in enhancing the capacity of B cells to extract and present immobilized antigens to CD4+ T cells in vitro using standardized experimental setups, as previously described (Yuseff and Lennon-Dumenil, 2013, Yuseff et al., 2011) (see STAR Methods for details). As expected from our in vivo results, both antigen extraction and presentation were enhanced upon stimulation of primary spleen B cells with BCR-ligand+ beads coated with Galectin-8 (Figures 5A and 5B). Similar results were obtained when stimulating the B lymphoma model cell line IIA1.6 (Figure S2). Strikingly, the amount of antigen extracted at early time points was significantly higher when Galectin-8 was present (Figures 5A, S2A, and S2B). After 120 min, the total amount of antigen extracted reached a plateau and was equal in both conditions (Figures 5A, S2A, and S2B). Importantly, in the absence of BCR engagement with specific antigens, Galectin-8 did not trigger antigen extraction by B cells (Figure S2C).

Figure 5.

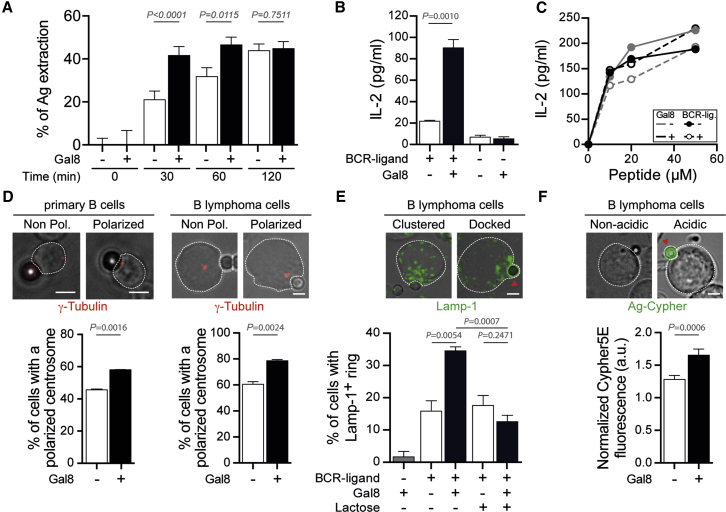

Extracellular Galectin-8 Favors Lysosome Secretion at the B Cell Synapse

(A) Quantification of the percentage of antigen (OVA) extracted from beads following incubation of primary spleen B cells with indicated beads and time. Values were normalized with respect to Ag-coated beads not engaged with B cells. n > 60 cells pooled from N = 2 independent experiments. Unpaired t test was used to assess statistical significance. Bar graphs indicate mean ± SEM.

(B) Antigen (Lack) presentation assay with spleen B cells in presence or not of exogenous Galectin-8. Bars show the mean ± SEM of triplicate and are representative of N = 2 independent experiments. Unpaired t test was used to assess statistical significance.

(C) Peptide controls for cells used in the antigen presentation assays shown in (B). Graph shows the mean of duplicates and is representative of N = 2 independent experiments.

(D) Representative images of non-polarized and polarized centrosomes (γ-Tubulin) in primary B cells (left) and a B lymphoma cell line (right). Scale bar, 3 μm. The lower panel shows the quantification of the percentage of cells having polarized their centrosome following 60-min stimulation with BCR-ligand+ beads containing or not Galectin-8. Paired t test was used to assess statistical significance. Bar graphs indicate mean ± SEM. n > 50 cell/bead conjugates assessed per condition pooled from N = 2 independent experiments (primary B cells) and N = 3 independent experiments (B cell line).

(E) Representative images of B cells harboring the characteristic Lamp-1+ ring of lysosomes docked at the cell-bead interface. Scale bar, 3 μm. The lower panel shows the quantification of the percentage of cells displaying Lamp-1+ rings upon stimulation with BCR-ligand+ beads containing or not Galectin-8 and in presence or not of 100 mM lactose for 60 min. n > 60 cell/bead conjugates assessed per condition pooled from N = 3 independent experiments. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess statistical significance. Bar graphs indicate mean ± SEM.

(F) Representative images of B cells harboring acidic synapse as revealed by the appearance of Cypher5E fluorescence on the BCR-ligand+ bead. Scale bar, 3 μm. The lower panel shows the quantification of the Cypher5E fluorescence intensity in cell-bead conjugates following a 90-min stimulation with BCR-ligand+ beads containing or not Galectin-8. Values were normalized with respect to the mean fluorescence intensity of beads that were not engaged in immune synapses. n > 270 cell/bead conjugates assessed per condition pooled from N = 2 independent experiments.

See also Figures S2, S3, and S4.

Consistent with these results, the processing and presentation of antigens, as revealed by the secretion of interleukin-2 (IL-2) by T cells, was significantly higher in the presence of Galectin-8 both in primary B cells and in the B cell line (Figures 5B and S2D). Peptide presentation showed no major differences between both conditions (Figures 5C and S2E), indicating that Galectin-8 does not affect cell surface levels of MHC-II molecules and does not influence B-T cell interactions per se. Importantly, in the presence of lactose, which inhibits Galectin binding, the effect of Galectin-8 was blocked, and the levels of antigen presentation were comparable to control conditions where Galectin-8 is absent (Figures S2D and S2E). Altogether, our results show that Galectin-8 also stimulates the capacity of B cells to extract and present immobilized antigens to CD4+ T cells in vitro.

Galectin-8 Enhances the Proteolytic Extraction of Immobilized Antigens at the B Cell Synapse

Two mechanisms have been proposed to promote the extraction of tethered antigens by B cells. While the first one involves B cell polarization and lysosome secretion within the synaptic cleft allowing the proteolytic extraction of the tethered antigens (Obino et al., 2017, Yuseff et al., 2011), the second one relies on cycles of B cell spreading and contraction coupled to mechanical extraction through pulling forces exerted by the motor protein Myosin II (Fleire et al., 2006, Harwood and Batista, 2011, Natkanski et al., 2013). To determine which pathway was affected by Galectin-8, we first evaluated the ability of this lectin to induce B cell spreading. To this end, B cells were seeded on poly-l-lysine (PLL)- or Galectin-8-coated coverslips, and their spreading area was monitored over time (Figure S3A). Strikingly, surface-immobilized Galectin-8 strongly enhanced B cell spreading (Figure S3B) and promoted the formation of actin protrusions, suggesting that this glycan-binding protein may strengthen cycles of actin-dependent cell spreading and contraction. Of note, B cells seeded on substrates containing Galectin-8 pretreated with lactose did not display a strong spreading response (Figures S3C and S3D). We confirmed that lactose blocked the interaction of this lectin with B cells by showing that pre-treatment of soluble recombinant Galectin-8 with lactose or thiodigalactoside (TDG) (another specific inhibitor of Galectin glycan binding sites) prevents Galectin-8 binding to the B cell surface (Figure S3E). Despite the effects observed on actin cytoskeleton remodeling, stimulation of B cells in the presence of Galectin-8 did not trigger higher levels of myosin regulatory light chain (MLC) phosphorylation, an indicator of Myosin II activation (Figure S3F), suggesting that proteolytic rather than mechanical extraction of antigens is being reinforced under these conditions.

Accordingly, when stimulated in the presence of extracellular Galectin-8, a higher proportion of B cells showed polarized centrosomes (Figure 5D). Analogous observations were made in a B lymphoma cell line, which was further used to study lysosome docking and polarity, because of their larger size. Indeed, enhanced recruitment and docking of lysosomes at the antigen-contact site was observed in the presence of Galectin-8, compared to cells stimulated with BCR ligands alone (Figure 5E). Of note, addition of lactose during B cell stimulation blocked the effect of Galectin-8, and the proportion of B cells with docked lysosomes at the immune synapse was comparable to control conditions where Galectin-8 is absent (Figure 5E). Consistent with these data, we observed that Galectin-8 stimulates the acidification of the B cell synapse as measured using beads coated with antigens coupled to the pH-sensitive dye Cypher5E (Figure 5F). Hence, Galectin-8 promotes the proteolytic extraction of bead-associated antigens by facilitating B cell polarization, lysosome recruitment, and secretion at the B cell synapse. Importantly, we further found that B cells lacking endogenous Galectin-8 expression normally polarized their centrosome and lysosomes to the immune synapse (Figure S4A) and only displayed a minor delay in their capacity to extract immobilized antigens (Figure S4B). In agreement with our in vivo data, these results argue for a role of Galectin-8 in the extracellular environment rather than a B cell-intrinsic function of this glycan-binding protein in its ability to enhance B cell responses.

Galectin-8 Enhances B Cell Functions by Interacting with the BCR

Finally, we searched for the B cell surface partner(s) of extracellular Galectin-8. To this end, GST-pull-down experiments and mass spectrometry analyses were conducted to identify Galectin-8 interacting proteins present within spleen B cell lysates. In agreement with previous studies showing that Galectin-8 interacts with the integrin LFA-1 (Cárcamo et al., 2006, Diskin et al., 2009, Vicuña et al., 2013), we found that both LFA-1 subunits, alpha-L and beta-2 (also known as CD11a and CD18, respectively), were present among the top hits (Table S1, red). Of note, proteins belonging to the B cell antigen BCR complex itself (Table S1, blue) as well as members of the Galectin family, Galectin-9 and the bait protein Galectin-8 (Table S1, green), were also found. The integrin LFA-1 represented an interesting candidate since it was described to promote B cell spreading but also, when engaged with its counter-receptor ICAM-1, decreases the threshold for BCR activation when antigen avidity is low (Carrasco et al., 2004, Saez de Guinoa et al., 2013). However, when repeating the Galectin-8 GST-pull-down assay and performing immunoblot experiments for this integrin, we were not able to confirm the interaction between LFA-1 and Galectin-8 in B cells (Figure 6A). In agreement with this result, pre-treatment of B cells with function-blocking antibodies against LFA-1 did not impair the extensive spreading observed when B cells are plated onto Galectin-8-coated surfaces (Figure 6B), nor the cell surface binding of soluble Galectin-8 (Figure 6C). Therefore, it is unlikely that the observed effects of Galectin-8 on B cell functions result from an interaction of this glycan-binding protein with surface LFA-1.

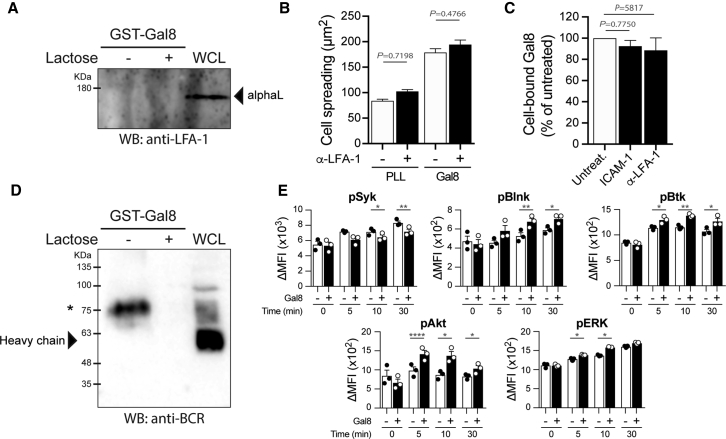

Figure 6.

Galectin-8 Interacts with the BCR

(A) GST-Galectin-8 pull-down experiments highlighting the absence of interaction between Galectin-8 and LFA-1 (lanes 1 and 2). Lane 3 shows the detection of LFA-1 in the whole-cell lysate (WCL). Representative of N = 4 independent experiments.

(B) Quantification of the spreading area of B cells pre-treated or not for 30 min with 10 μg/mL function-blocking anti-LFA-1 antibody and seeded on poly-l-lysine (PLL)- or Galectin-8-coated coverslips. n > 60 cells per condition pooled from N = 3 independent experiments. ANOVA test followed by a Sidak’s multiple-comparison test was used to assess statistical significance. Bar graphs indicate mean ± SEM.

(C) Flow cytometry quantification of cell-bound Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated Galectin-8 following a 60-min incubation with B cells pre-treated or not for 30 min with 2 μg/mL recombinant ICAM-1 or 10 μg/mL function-blocking anti-LFA-1 antibody. Values were normalized with respect to the untreated condition in each experimental replicate. Data are pooled from N = 2 independent experiments. ANOVA test followed by a Sidak’s multiple-comparison test was used to assess statistical significance. Bar graphs indicate mean ± SEM.

(D) GST-Galectin-8 pulls down the BCR from B cell extracts (lane 1), which is inhibited in presence of 100 mM lactose (lane 2), indicating the dependency of Galectin-8/glycan interactions. Lane 3 shows the detection of the BCR in the whole-cell lysate (WCL). ∗The higher molecular weight could correspond to a highly glycosylated form of the BCR or a stable complex between the Ig heavy and light chain. Representative of N = 3 independent experiments.

(E) Flow cytometry analysis of the phosphorylation status of BCR-downstream signaling molecules upon stimulation of primary spleen B cells with BCR-ligand+ beads containing or not Galectin-8 for indicated times. Values were normalized with respect to the non-stimulated condition for each mouse. Each dot on the bar graphs corresponds to cells purified from independent mice. Data are representative of N = 2 independent experiments. Ratio t test was used to assess statistical significance. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Bar graphs indicate mean ± SEM.

See also Table S1.

We next investigated a potential interaction of Galectin-8 with the BCR itself. The interaction between both proteins was confirmed by pull-down assays, where we found that GST-Galectin-8 formed a complex with the BCR (Figure 6D). Of note, this interaction was inhibited by the addition of lactose showing the glycan-specificity of the interaction (Figure 6D, lactose +). Given that the BCR controls both antigen uptake and elicits downstream signaling upon ligand engagement, we evaluated whether Galectin-8 regulates BCR downstream signaling pathways. Our results show that while Galectin-8 barely affected Syk and ERK signaling, it enhanced the phosphorylation of Blnk, Btk, and Akt, which were higher and more sustained in time (Figure 6E). Interestingly, Btk and Akt signaling molecules are part of the PI3K pathway involved in the determination of B cell activation and fate upon antigen encounter (Limon and Fruman, 2012). Alternatively, the Akt signaling pathway has also been described to regulate antigen presentation by macrophages and dendritic cells through the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-dependent regulation of the lysosomal activity (Saric et al., 2016). Altogether, these results suggest that Galectin-8 was unlikely enhancing antigen extraction and presentation by modulating integrin activity but rather by directly modulating the signaling properties of the BCR upon particulate-antigen encounter.

Discussion

We here show that Galectin-8 is expressed in the SCS and promotes antigen extraction and presentation by B lymphocytes, reinforcing the cooperation between T and B cells in vivo. We further highlight using quantitative in vitro assays that this effect of Galectin-8 is mediated at least in part by (1) interacting directly with the BCR to strengthen downstream signaling via the PI3K pathway and (2) enhancing the recruitment and secretion of lysosomes at the B cell synapse. Higher antigen extraction translates into longer phases of interaction between B cells and antigen presenting cells in the B cell follicle as highlighted by intra-vital microscopy. Galectin-8 therefore emerges as an ECM-associated protein that acts as an extracellular cue to stimulate B cell responses to T cell-dependent antigens in vivo.

Galectins are considered part of the environmental stimuli that shape immune responses depending on their local concentration and glycosylated ligands exposed on the surface of immune cells (Rabinovich and Croci, 2012, Rabinovich and Toscano, 2009). Interestingly, during differentiation and/or activation, immune cells can change the glycosylation patterns of their receptors and thereby modulate interactions with specific Galectins (Marth and Grewal, 2008). Galectin-1 and -8 were both shown to promote the differentiation of LPS-treated B cells into antibody-secreting plasma cells (Anginot et al., 2013, Tsai et al., 2008, Tsai et al., 2011). Whereas higher concentrations of Galectin-8 trigger antigen-independent CD4+ T cell proliferation, lower concentrations of this lectin act as a co-stimulatory signal that favors antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses (Cattaneo et al., 2011, Tribulatti et al., 2009). We found that, under inflammatory conditions, the expression of Galectin-8 increased significantly within lymph nodes. However, due to the lack of specific antibodies, we could not determine which specific cell types were producing Galectin-8. Interestingly, lymph node-resident cells, such as lymphatic endothelial cells, express Podoplanin, a transmembrane glycoprotein, recently described to interact with Galectin-8 (Cueni and Detmar, 2009). Thus, along with detecting the cell types that produce Galectin-8, it would be important to study receptors located at the surface of antigen-presenting cells, which could immobilize Galectin-8 at their cell surface to modulate their effector functions. Additionally, changes in glycosylation patterns at the surface of B cells, generated by LPS treatment, could equally contribute to enhance interactions with Galectin-8. Moreover, the immunoregulatory effects of Galectins are frequently altered under pathological conditions such as autoimmunity (Pardo et al., 2017, Sarter et al., 2013). The sera of patients suffering from SLE or multiple sclerosis contain autoantibodies with functional blocking activity against Galectin-8 (Cárcamo et al., 2006, Massardo et al., 2009, Pardo et al., 2017, Vicuña et al., 2013), suggesting that this lectin could play a role in B cell homeostasis and function. However, the impact of Galectin-8 in regulating antigen presentation and B cell responses in vivo had not been explored until now.

The tight coupling between arrests in cell motility and the establishment of a stable immune synapse is critical for B cells to efficiently extract and process antigens in vivo. We provide evidence for the role of Galectin-8 in both processes and reveal potential mechanisms involved. We show that Galectin-8 triggers the formation of actin protrusions and extensive cell spreading in B cells, which could favor the formation of a stable immune synapse. Indeed, cortical actin cytoskeleton remodeling plays a key role in regulating the adhesive properties of B cells at the site of antigen encounter by promoting a spreading response and controlling receptor signaling (Mattila et al., 2016). Additionally, actin-binding proteins, such as Vinculin, can stabilize LFA-1 at the synaptic membrane and strengthen the adhesive capacity of B cells (Saez de Guinoa et al., 2013). Galectin-8 was shown to bind to LFA-1 in T cells and to promote actin rearrangements by activating Rho and Rac signaling pathways (Cárcamo et al., 2006, Diskin et al., 2009, Vicuña et al., 2013). However, our data reveal that the effect of Galectin-8 on actin cytoskeleton remodeling does not rely on its direct binding to LFA-1. This is consistent with our results showing that Galectin-8 binds to the surface of B cells, independently of LFA-1, and can interact directly with the BCR. Accordingly, we observe that Galectin-8 strengthens BCR downstream signaling, particularly the PI3K pathway, which could also promote actin cytoskeleton remodeling by activating downstream targets, such as the small GTPases Rac1 and Rac2 (Arana et al., 2008, Brezski and Monroe, 2007). Noticeably, we have recently shown that the formation of the B cell immune synapse correlates with a decrease in the fraction of F-actin associated with the centrosome of B cells, a process required for B cell polarization and efficient extraction and presentation of tethered antigens (Obino et al., 2016). Whether Galectin-8 enhances B cell functions by modulating cortical and/or centrosomal pools of F-actin shall now be investigated.

As mentioned above, tethered antigens are extracted through lysosome and protease secretion when presented on rigid surfaces, whereas they are extracted through mechanical forces exerted by the motor protein Myosin II when presented on flexible surfaces such as the plasma membrane of antigen-presenting cells (Natkanski et al., 2013, Obino et al., 2017, Yuseff et al., 2011). However, stimulation of B cells in the presence of Galectin-8 did not trigger higher levels of MLC phosphorylation, an indicator of Myosin II activation (Figure S3F), suggesting that proteolytic rather than mechanical extraction of antigens is being reinforced under these conditions. Nevertheless, the absence of Myosin II activation could be due to the rigid nature of the substrate in which antigens are presented in our assay, where proteolytic-dependent extraction is favored. In this context, we cannot rule out that Galectin-8 might promote Myosin II activation when antigens are recognized on more flexible surfaces and thereby enhance their mechanical extraction. This raises the importance to determine whether co-stimulatory signals act in concert with physical cues of the environment to elicit different responses to immobilized antigens. In this regard, a recent study revealed that, in the presence the TLR9 agonist, CpG, B cells do not seem to exert pulling forces to extract antigens immobilized on plasma membrane sheets, considered flexible substrates (Akkaya et al., 2018), revealing that the mode of antigen extraction can be modulated in the presence of co-stimulatory factors. Thus, focusing on the potential cross talk between co-stimulatory molecules, such as Galectins, and mechanical cues shall provide insights on how antigen extraction and processing are regulated at the B cell synapse in vivo. How is the antigen extraction capacity of B cells controlled by extracellular cues in the context of lymphoid organs? Our results suggest that the presence of Galectin-8 allows prolonged interactions/attachment between B cells and antigen-presenting cells (APCs), thereby favoring the recruitment of MHC-II-containing lysosomes toward the immune synapse, which can contribute to further antigen extraction and processing. Such a mechanism can enrich the repertoire of antigenic peptides presented by B cells, even when Myosin II bypasses the need for proteolytic extraction of tethered antigens. Thus, Galectin-8 emerges as an extracellular cue that can tune B cell responses in vivo and in pathological situations.

Galectins can modulate the signaling capacity of immune cells by interacting directly with immune receptors at the synaptic membrane. For instance, multivalent interactions between Galectin-3 and the T cell receptor (TCR) can restrict lateral movements of this receptor at the immune synapse, thereby increasing the threshold for TCR signaling (Demetriou et al., 2001). Although Galectin-8 does not form multivalent oligomers as Galectin-3, a non-quantitative proteomic analysis of Galectin-8 binding partners in B cells revealed that Galectin-8 interacts directly with the BCR (Table S1), which was also supported by a pull-down assay showing that Galectin-8 binds to the BCR. Analogously, Galectin-9 was recently shown to interact directly with the BCR and CD45 and to suppress BCR downstream signaling by restricting the lateral mobility of the receptor and favoring its association with inhibitory molecules (Cao et al., 2018). In contrast to the effect of Galectin-9, we did not observe an inhibition of BCR signaling in the presence of Galectin-8. Moreover, we detected a higher and more sustained activation of the PI3K signaling pathway in B cells stimulated with BCR ligands plus Galectin-8 compared to the ligand alone, suggesting that B cell activation and fate are upregulated by this lectin (Saric et al., 2016). The canonical PI3K/Akt pathway also regulates lysosome tubulation triggered by LPS stimulation in macrophages and dendritic cells (Saric et al., 2016). Whether the effect of Galectin-8 on the recruitment and secretion of lysosomes at the immune synapse is regulated by the PI3K pathway and induces changes in lysosome morphology remains to be addressed. Notably, Galectin-8 alone was unable to trigger GC responses in vivo, nor induce BCR signaling or support antigen processing and presentation in vitro, suggesting that enhanced B cell activation results from the concerted action of Galectin-8 and BCR ligands. Under this perspective, it will be interesting to determine whether B cells stimulated by antigens further expose ligands that promote interactions with Galectin-8.

In addition to their extracellular activity, Galectins are also known to interact with endosomal and lysosomal compartments, where they can sense membrane damage caused by invading pathogens and, in the case of Galectin-8, also trigger antibacterial autophagy (Boyle and Randow, 2013, Thurston et al., 2012). In terms of our model, B cells isolated from Galectin-8 knockout (KO) mice did not show any defects in the polarization of the centrosome and associated lysosomes at the immune synapse; however, they did display a slightly lower capacity to extract immobilized antigens at earlier time points, compared to WT cells. A plausible explanation is that intracellular Galectin-8 could be important to maintain lysosome homeostasis as it connects lysosomes to the autophagy pathway (Boyle and Randow, 2013). Consequently, the absence of Galectin-8 can indirectly affect lysosome-associated functions, such as the degradation of immobilized antigens. Alternatively, B cells themselves might produce Galectin-8 and locally secrete this lectin at the immune synapse to promote BCR signaling in an autocrine fashion and thereby further enhance antigen extraction. Overall, our results favor a role for extracellular Galectin-8, secreted by other cell types and possibly B cells themselves, in regulating the threshold for B cell activation and response to membrane-tethered antigens

Altogether, we bring forward evidence on the role of an extracellular cue, Galectin-8, in regulating B cell responses in vivo. We provide the molecular basis behind its role in B cell activation by showing that Galectin-8 acts as a co-stimulator, together with BCR ligands, to promote arrest phases in B cell motility and favor the formation of a stable immune synapse (IS). At this level, Galectin-8 promotes proteolytic extraction of tethered antigens by enhancing lysosome recruitment and secretion at the immune synapse, thereby leading to efficient antigen processing and presentation.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| rabbit anti-γ-Tubulin | Abcam | Cat#Ab11317; RRID: AB_297921 |

| rat anti-Lamp-1 (CD107a) | BD PharMingen | Cat #553792; RRID: AB_2134499 |

| AlexaFluor647-conjugated rat anti-CD169 | AbD Serotec | Cat#MCA947A647; RRID: AB_10545834 |

| mouse anti-CD45.2-FITC | BD PharMingen | Cat#553772; RRID: AB_395041 |

| rat anti-CD4-APC | eBioscieince | Cat#17-0041-83; RRID: AB_469321 |

| rat anti-CD45R/B220-PE | BD PharMingen | Cat#553090; RRID: AB_394620 |

| rat anti-CXCR5-PE-Cy7 | BD PharMingen | Cat#560617; RRID: AB_1727521 |

| hamster anti-PD1-PerCP-eFluor710 | eBioscience | Cat#46-9985-82; RRID: AB_11150055 |

| rat anti-GL7-BV421 | BD Horizon | Cat#562967; RRID: AB_2737922 |

| hamster anti-FAS-BV510 | BD Horizon | Cat#563646; RRID: AB_2738345 |

| biotinylated rabbit anti-HEL | Abcam | Cat#Ab34620; RRID: AB_776112 |

| Streptavidin-APC-eFluor780 | eBioscience | Cat#47-4317-82; RRID: AB_10366688 |

| Anti-phospho-Myosin Light Chain (pSer19) | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#M6068; RRID: AB_262024 |

| PE Mouse Anti-ERK1/2 (pT202/pY204) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 612566; RRID: AB_399857 |

| Alexa Fluor® 647 Mouse Anti-ZAP70 (PY319)/Syk (PY352) | BD Biosciences | Cat#557817; RRID: AB_396884 |

| Alexa Fluor® 488 Mouse anti-BLNK (pY84) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 558444; RRID: AB_2064951 |

| BV421 Mouse Anti-Btk (pY223)/Itk (pY180) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 564848; RRID: AB_2738982 |

| PE-CF594 Mouse Anti-Akt (pS473) | BD Biosciences | Cat#562465; RRID: AB_2737620 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| CypHer5E NHS Ester | GE Healthcare | Cat#PA15401 |

| Recombinant rat Galectin-8 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# G3670-100UG |

| Recombinant HEL | Recombinant Protein platform, UMR144, Institut Curie | N/A |

| Recombinant ovalbumin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A5503 |

| Recombinant Lack | Recombinant Protein platform, UMR144, Institut Curie | N/A |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| BD optEIA Mouse IL-2 ELISA set | BD Biosciences | Cat#555148 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Proteomic analysis of Galectin-8 interacting proteins | This paper | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/login; Project accession: PXD011522 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Mouse IgG+ B lymphoma cell line IIA1.6 | Lankar et al., 2002 | N/A |

| Mouse LMR7.5 T cell hybridoma | Malherbe et al., 2000 | N/A |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: Lgals8−/−: C57BL/6NTac- Lgals8tm1(KOMP)Vlcg | KOMP Repository | Cat#VG14305 |

| Mouse: MD4: C57BL/6-MD4 | Goodnow et al., 1988 | N/A |

| Mouse: MHC-II-GFP: C57BL/6- I-Abβ-GFP | Boes et al., 2002 | N/A |

| Mouse: SWHEL: C57BL/6-SWHEL | Marion Espéli (Phan et al., 2003) | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| qRT-PCR primer for Lgals8 (the exact sequence is proprietary but is included in the target sequence caagaacaaattccaggtggctgtg) | Life Technologies | Cat#4331182_Mm01332239-m1 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Prism 7.0d | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| Fiji (ImageJ) | Schindelin et al., 2012 | https://fiji.sc/#download |

| Imaris | Bitplane | http://www.bitplane.com/ |

| FlowJo v10 | FlowJo, LLC | https://www.flowjo.com/ |

| Other | ||

| Polybead® Amino Microspheres 3.00 μm | Polyscience | Cat#17145-5 |

| 0.2 μm neutravidin red fluorescent-microspheres | Life Technologies | Custom (similar product Cat#F8774) |

Contact for Reagent and Resource Sharing

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, María-Isabel Yuseff (myuseff@bio.puc.cl).

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Mice

Sperm from Lgals8−/− mice (Mouse Project ID VG14305, Lgals8tm1(KOMP)Vlcg deleted allele) were purchased from the Knockout Mouse Project (KOMP) Repository (University of California, Davis). Lgals8−/− mice were generated by in vitro fertilization of C57BL/6 WT mice. Lgals8−/− mice carry a LacZ expression cassette at the Lgals8 endogenous locus. Lgals8−/− mice were breeded with C57BL/6 CD45.1 mice to obtain Lgals8−/− CD45.1 mice. The transgenic mouse line MD4, whose B cells carry transgenic (Tg) BCR specific for Hen Egg Lysozyme (HEL) (Goodnow et al., 1988), and the IAb-β-GFP genetically targeted mice (MHC-II-GFP) (Boes et al., 2002) were crossed to obtained MD4 Tg/I-Abβ-GFP mice. All mice were housed at Département de Cryopréservation, Distribution, Typage et Archivage animal (CDTA) (TAAM, UPS44, Orléans, France) in an accredited specific-pathogen-free animal facility except for SWHEL mice (Phan et al., 2003) housed in the specific-pathogen-free Animex MIPSIT facility (Clamart, France, agreement number C9202301). Experiments and sacrifices were performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the French Veterinary Department and the ethical committee from the Institut Curie. Spleens from SWHEL mice and OT-II mice were kindly provided by Marion Espéli and Olivier Lantz (Institut Curie, Paris), respectively. For all experiments, male and female (donors) and only female (recipients) mice between 6 and 10-weeks of age were used. Littermates were randomly assigned to experimental groups.

Cell lines

The mouse IgG+ B lymphoma cell line IIA1.6 (derived from the A20 cell line [ATCC #: TIB-208], which derives from an old BALB/c AnN mouse [sex and precise age unknown) (Lankar et al., 2002) and the LMR7.5 T cell hybridoma (derived from a 8-12 weeks old transgenic B10.D2 mouse carrying the rearranged TCR β chain of the Lack-specific LMR16.2 T cell hybridoma (16.2β) [sex unknown]), which recognizes I-Ad-Lack156–173 complexes (Malherbe et al., 2000) were cultured in CLICK medium (RPMI 1640 – GlutaMaxTM-I supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 1% penicillin–streptomycin, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol and 2% sodium pyruvate) (Le Roux et al., 2007). All cell culture products were purchased from GIBCO/Life Technologies. All in vitro experiments were conducted in 50% CLICK / 50% RPMI 1640 – GlutaMaxTM-I. All cell lines were monthly checked for the presence of mycoplasma.

Primary cells

Wild-type (C57BL/6) or HEL-specific (MD4 or SWHEL) resting mature IgM+-IgD+ B cells were purified from spleens of male and female 6-10 weeks old mice as described (Vascotto et al., 2007) using mouse negative B Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi) according to manufacturer’s instructions. OVA-specific OT-II CD4+ T cells were purified from spleens using mouse negative CD4+ T Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi) according to manufacturer’s instructions. All primary cells were used extemporaneously.

Method Details

Reagents and antibodies

The Lack antigen was produced and purified by the Recombinant Protein platform (UMR144, Institut Curie, Paris, France). Lack peptide (aa 156-173) was synthetized by PolyPeptide Group. LPS from Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium and recombinant rat Galectin-8 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Cypher5E was purchased from GE Healthcare.

The following primary antibodies were used for immunofluorescence: rabbit anti-γ-Tubulin (Abcam, #Ab11317, 1/1000), rat anti-Lamp-1 (CD107a; BD PharMingen, #553792, 1/400), polyclonal rabbit anti-OVA (1/500), AlexaFluor647-conjugated rat anti-CD169 (AbD Serotec, #MCA974A647, 1/50). The following secondary antibodies were used: Cy3-conjugated F(ab’)2 donkey anti-rabbit (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 1/200) and AlexaFluor488- and 647-conjugated donkey anti-rat (Life Technologies, 1/200). 4’,6-Diamidino-2-phenyindole (DAPI, Sigma Aldrich, 1/5000) was used to counterstain nuclei.

RNA extraction and Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA extraction was performed from 30 mg of tissues or 10x106 cells using Nucleospin RNA kit II (Macherey Nagel) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was performed with 1 μg RNA using the SuperScript® VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Galectin-8 (primer: Mm01332239-m1 Lgals8, Life Technologies) mRNA levels were assessed using TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Values were normalized with respect to Gapdh expression levels. For LPS-induced systemic inflammation, C57BL/6 WT mice received one retro-orbital injection of 50, 20 or 10 μg LPS (in 200 μl 1x PBS) 6 h prior to RNA extraction.

Staining of lymph node cryosections

Lymph nodes were fixed by perfusion of 4% paraformaldehyde in PB buffer (0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4), dehydrated in 30% sucrose and serial cryosectioned in 5 μm-thick sections (except for in vivo antigen uptake assays for which 30 μm-thick sections were performed). Galectin-8 expression was followed by detecting β-Galactosidase activity in cells that possess an active Lgals8 promoter, as an alternative to the use of commercial antibodies against Galectin-8, which did not provide specific staining in our hands. For β-Galactosidase staining, sections were incubated over-night at 37°C with β-Gal staining solution, according to (Segovia-Miranda et al., 2015), and when indicated later stained with 5% aqueous eosin. For histo-immunofluorescence labeling, sections were blocked with TBS/BSA/Tween20 (1x/3%/0.3%) for 20 min and incubated over-night at 4°C with primary antibodies and 60 min with secondary antibodies in TBS/BSA (1x/3%). All sections were then mounted with Entellan for imaging.

Preparation of BCR-ligand-coated beads

For in vitro experiments, 4x107 3 μm latex NH2-beads (Polyscience) were activated with 8% glutaraldehyde (Sigma Aldrich) for 2 h at room temperature as previously described (Obino et al., 2016, Yuseff et al., 2011). Beads were washed with 1x PBS and incubated over-night at 4°C with different ligands: 100 μg/ml of either F(ab′)2 goat anti-mouse IgG or F(ab’)2 goat anti-mouse IgM (both from MP Biomedical) in combination or not with 100 μg/ml of either ovalbumin (OVA), the Leishmania major antigen Lack and/or 0.5 μM rGalectin-8. For in vivo experiments, 5 μl of 0.2 μm neutravidin red fluorescent-microspheres stock solution (Life Technologies) were washed in PBS/BSA (1x/1%) and incubated over-night with biotinylated HEL or BSA (7.5 μg and 15 μg, respectively) in combination or not with biotinylated rGalectin-8 (7.5 μg) in 500 μl PBS/BSA (1x/1%). Microspheres were washed with 1x PBS and resuspended in 125 μl 1x sterile PBS. The effective amounts of HEL immobilized on microspheres were assessed by western blotting (See Immunoblotting section for details).

Immunoblotting

Coated microspheres were resuspended in 1x Laemmli buffer and incubated 10 min at 95°C. Supernatants were collected and separated onto mini-PROTEAN TGX SDS-PAGE gels. Following transfer onto PVDF membranes (Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer), membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk resuspended in TBS-Tween-20 (1x/0.05%) and incubated over-night at 4°C with primary antibodies followed by 60 min incubation with secondary antibodies. Western blots were developed with Clarity Western ECL substrate and chemiluminescence was detected using the ChemiDoc imager (all from BioRad).

Two-photon microscopy and cell tracking

1 to 3x106 IAb-β-GFP-expressing MD4 (HEL-specific) or WT (HEL non-specific) B cells were adoptively transferred by retro-orbital injection (in 200 μl 1x sterile PBS) into C57BL/6 WT recipient mice 24 h prior to be immunized with indicated 0.2 μm microspheres by footpad injection (∼2x109 microspheres in 25 μl, corresponding to ∼1.5 μg of injected HEL). 20 min post-immunization, mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of a ketamine/xylazine cocktail (100 mg/ml and 20 mg/ml, respectively. 100 μl per 20 g mouse body weight) and the popliteal lymph node draining the site of injection was prepared for two-photon imaging. The two-photon laser-scanning microscopy (TPLSM) setup used was a LSM510 Meta (Zeiss) coupled to a Maitai DeepSee femtosecond laser (690–1020 nm) (Spectra-Physics). The excitation wavelength was 900 nm. For analysis of cell motility, nine consecutive 230 × 230 μm2 images, with 4 μm z-spacing with a 40x/1.0 NA objective (Zeiss) were taken every 30 s during 30 min. Images were average-projected, denoised (median filter, radius 2 px) with Fiji (ImageJ) software (Schindelin et al., 2012) and automatic tracking of individual cells was performed with Imaris software (Bitplane). Individual tracks were manually checked and corrected when required. 3D reconstruction shown in Figure 2B was obtained by interpolation of the brightest points.

In vivo antigen uptake

2x106 CFSE-labeled (5 μM/107 cells, in 1x sterile PBS, 15 min at 37°C) MD4 (HEL-specific) B cells were adoptively transferred by retro-orbital injection (in 200 μl 1x sterile PBS) into C57BL/6 WT recipient mice 24 h prior to be immunized with indicated 0.2 μm microspheres by footpad injection (see Two-photon microscopy and cell tracking section for details). 16 h post-immunization, mice were sacrificed and the popliteal lymph nodes draining the site of injection were harvested and prepared for cryosectioning (See Staining of lymph node cryosections section for details). 90 z stack (spacing 0.35 μm) images were acquired on a confocal laser scanning TCS SP8 microscope (Leica) equipped with a 40x/1.3 NA objective (Leica). See Quantification and Statistical Analysis section for quantification details.

In vivo antigen presentation

To assess the effect of exogenous Galectin-8 on T-B cooperation in vivo, 2x106 SWHEL CD45.2 B cells and 0.5x106 OT-II CD4+ CD45.2 T cells were adoptively transferred by retro-orbital injection (in 200 μl sterile 1x PBS) into C57BL/6 Lgals8+/+ or Lgals8−/− CD45.1 recipients. 24 h later, recipient mice were immunized by footpad injection of indicated 0.2 μm microspheres (see Two-photon microscopy and cell tracking section for details). 8 days’ post-immunization, mice were sacrificed and the popliteal lymph nodes draining the site of immunization were harvested and treated with collagenase IV and DNase I for 30 min at 37°C to obtain single cell suspensions. Following Fc receptor blocking with rat anti-mouse CD16/32 antibodies (Mouse BD Fc Block, BD PharMingen), single-cell suspensions were incubated on-ice for 60 min with HEL recombinant protein (4 μg/ml) and rat anti-mouse CXCR5-PE-Cy7 (BD PharMingen, #560617, 1/50) diluted in PBS/BSA/EDTA (1x/2%/2mM). Cells were then washed and incubated on-ice for 30 min with mouse anti-mouse CD45.2-FITC (BD PharMingen, #553772), rat anti-mouse CD4-APC (eBioscieince, #17-0041-83), rat anti-mouse CD45R/B220-PE (BD PharMingen, #553090), rat anti-mouse GL7-BV421 (BD Horizon, #562967), hamster anti-mouse FAS-BV510 (BD Horizon, #563646), hamster anti-mouse PD1-PerCP-eFluor710 (eBioscience, #46-9985-82, all 1/200), biotinylated rabbit anti-HEL (Abcam, #Ab34620, 1/500) and Streptavidin-APC-eFluor780 (eBioscience, #47-4317-82, 1/100) diluted in PBS/BSA/EDTA (1x/2%/2mM). Acquisitions were performed on a FACS Verse (BD Biosciences) and data analysis was carried out with FlowJo v10.

Antigen extraction and B cell polarization

0.25x106 B lymphoma or 0.4x106 spleen B cells were plated on poly-L-lysine–coated slides and stimulated with BCR-ligand+ beads (cell:beads ratio: 1:2) containing OVA ± Gal8 for indicated time at 37°C, fixed in 4% PFA for 12 min at room temperature, quenched and blocked with PBS/BSA/Glycine (1x/2%/100 mM) and stained for OVA, the centrosome (γ-Tubulin) and the lysosomes (Lamp-1). For primary B cell polarization, 0.4x106 spleen B cells purified from either Lgals8+/+ or Lgals8−/− mice were incubated with BCR-ligand+ beads containing or not Galectin-8 for indicated time, fixed and stained for the centrosome (γ-Tubulin) and lysosomes (Lamp-1). Fixed cells were incubated 45-60 min with primary antibodies and 30 min with secondary antibodies in PBS/BSA/Saponin (1x/0.2%/0.05%). Z stack (0.5 μm spacing) images of fixed cells were acquired on an inverted spinning disk confocal microscope (Roper/Nikon) with a 60x/1.4 numerical aperture (NA) oil immersion objective. See Quantification and Statistical Analysis section for quantification details.

In vitro antigen presentation

0.1x106 B lymphoma cells were incubated with BCR-ligand+ beads containing Lack ± Gal8 for 3 h or with peptide control for 1 h. Cells were washed with 1x PBS, fixed in ice-cold Glutaraldehyde (0.01% in 1x PBS) for 1 min and quenched with Glycine (100 mM in 1x PBS). B cells were then incubated with the Lack specific LMR7.5 T cell hybridoma in a 1:1 ratio for 24 h. Supernatants were collected and IL-2 cytokine production was assessed using BD optEIA Mouse IL-2 ELISA set (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vitro synapse acidification

0.25x106 B lymphoma cells were incubated with BCR-ligand+ beads containing Cypher5E ± Gal8 for 90 min. Z stack (0.5 μm spacing) images of live cells were acquired on an inverted spinning disk confocal microscope (Roper/Nikon) with a 60x/1.4 numerical aperture (NA) oil immersion objective. See Quantification and Statistical Analysis section for quantification details.

Expression of rGal8 in E.coli

Expression of recombinant GST-Gal8 was induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-h-digalactopyranoside (Invitrogen) for 5 h. GST-Gal8 protein was purified by affinity chromatography on glutathione-Sepharose as described by the manufacturer. The GST-Gal8 column was treated with penicillin/streptomicyn at 4°C for 16 hr. Gal8 was released from GST-Gal8 linked to glutathione–Sepharose by thrombin treatment (10 U/mg of fusion protein) for 4 h at room temperature and collected under sterile conditions. Endotoxins were eliminated using Pierce High-Capacity Endotoxin removal resin as described by the manufacturer.

GST Pull-down

2.5x106 spleen B cells were lysed for 1 h at 4°C with lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM, EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.1 mM Pepstatin and 0.1 mM Leupeptin anti proteases) for 1 h at 4°C. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation for 10 min at 20,000 g. 300 μg of total proteins from cell extracts were incubated with 30 μl of GST-Gal8 linked to glutathione–Sepharose beads. Competence experiments were performed by pre-incubating GST-Gal8 beads with 100 mM lactose, for 1 h at 4°C. The beads were then washed in PBS, suspended and boiled in loading buffer (0.5M Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 20% SDS, 5% beta-mercaptoethanol (v/v), 100 mM DTT, bromophenol blue). Bound BCR was resolved by 7.5% SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgM and visualized by ECL.

Proteomics

To identify Galectin-8 interacting proteins by proteomic analysis, GST pull-down experiments were conducted as described above, except that following the incubation with B cell extracts, the GST-Gal8-beads were extensively washed in cold 1x PBS and binding partners eluted with 200 mM Lactose (1x cold PBS). Eluates were adjusted to 10 mM beta-mercaptoethanol and 0.02% SDS and denatured at 95°C for 5 min and after cooling incubated with 42 U/ml PNGase F (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 hours at 37°C to deglycosylate the proteins. Eluted proteins were then precipitated using trichloroacetic acid (TCA), resuspended in 1x Laemmli buffer, incubated 10 min at 95°C and separated using NuPAGE Bis-Tris 4%–12% gels in MOPS buffer (Invitrogen). Gels were then stained with Coomassie blue, three plugs for each sample were cut and after destaining steps, in-gel trypsin digestion was performed. Proteins from plugs were reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), alkylated with 55 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) and incubated with 20 μL of 25 mM NH4HCO3 containing 12.5 μg/ml sequencing-grade trypsin (Promega) overnight at 37°C. Resulting digested peptides from each plug were analyzed on a Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid mass spectrometer coupled to an Easy-spray nanoelectrospray ion source and an Easy nano-LC Proxeon 1000 liquid chromatography system (all from Thermo Scientific). Chromatographic separation of the peptides was achieved by an Acclaim PepMap 100 C18 pre-column and a PepMap-RSLC Proxeon C18 column at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. The solvent gradient consisted of 95% solvent A (water, 0.1% (v/v) formic acid) to 35% solvent B (100% acetonitrile, 0.1% (v/v) formic acid) over 98 minutes for a total gradient time of 2 hours. The orbitrap cell analyzed the peptides in full ion scan mode, with the resolution set at 120 000 with a m/z range of 350 - 1550. Higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) activation with a collisional energy of 28% was used for peptide fragmentation with a quadruple isolation width of 1.6 Da. The linear ion trap was employed in top-speed mode in order to acquire the MS/MS data. Maximum ion accumulation times were set to 250 ms for MS acquisition and 60 ms for MS/MS acquisition in parallelization mode. For the identification step, all MS and MS/MS data were processed with the Proteome Discoverer software (Thermo Scientific, version 1.4) and with an in-house Mascot search engine (Matrix Science, version 2.5.1). The mass tolerance was set to 7 ppm for precursor ions and 0.5 Da for fragments. The following modifications were allowed: oxidation (M), carbamidomethylation (Cys), phosphorylation (Ser, Thr, Tyr), acetylation (N-term of protein), deamidation (Asn, Gln). The SwissProt database (10/2014) with the Mus musculus taxonomy was used to identify proteins. Peptide FDR (False Discovery Rate) were calculated with the Percolator algorithm. Protein were considered as identified if their mascot scores were above 50 and if more than 2 peptides per protein were identified.

B cell spreading

B lymphoma cells were seeded on coverslips coated with poly-L-lysine or 20 μg Galectin-8 for indicated time, fixed with 4% PFA for 10 min and stained with Alexa-Fluor488-conjugated Phalloidin. To assess the glycan specificity binding of Galectin-8, B cells were plated on indicated coverslips in presence of 100 mM sucrose or lactose for 60 min. To assess the dependency of Galectin-8 binding to B cell surface LFA-1, B cells were pre-treated with 10 μg/ml of function-blocking anti-LFA-1 antibody (Biolegend, #101109) before being plated on indicated coverslips for 60 min. Z stack (0.5 μm spacing) images of fixed cells were acquired on an inverted spinning disk confocal microscope (Roper/Nikon) with a 60x/1.4 numerical aperture (NA) oil immersion objective.

Soluble Galectin-8 binding assay

Recombinant Galectin-8 was coupled to AlexaFluor488 using AlexaFluor488-microscale protein labeling kit (Invitrogen, #A30006) according to manufacturer’s instructions. 20 μg of AlexaFluor488-conjugated Galectin-8 (Gal8-488) were pre-treated with 20 mM of either sucrose, lactose (Sigma-Aldrich) or thiodigalactoside (TDG) (Carbosynth, Batch# OS043971301) for 30 min, then incubated with B cells for 60 min, washed and the cell-bound fraction of Gal8-488 detected by flow cytometry. A similar approach was used to assess the dependency of Galectin-8 binding to B cell surface LFA-1. In these conditions, B cells were pre-treated for 30 min with 2 μg/ml of soluble recombinant ICAM-1-Fc (Biolegend, #553004) or 10 μg/ml of function-blocking anti-LFA-1 antibody (Biolegend, #101109) to prevent the potential interaction of Galectin-8 with LFA-1 prior to be incubated for 60 min with Gal8-488.

PhosphoFACS

1x106 spleen B cells were incubated on-ice in RPMI 1640 – GlutaMaxTM-I (without serum) for 30 min prior to be stimulated with BCR-ligand+ beads (cell:bead ratio 1:1) containing or not Galectin-8 for indicated time. Cells were washed in ice-cold 1x TBS, fixed with ice-cold methanol for 30 min on ice. Cells were stained with either a rabbit anti-phospho-Myosin Light Chain (pSer19) antibody followed by an AlexaFluor647-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (#A21244, Invitrogen) or with a PE-conjugated anti-ERK1/2 (pT202/pY204), AlexaFluor647-conjugated anti-ZAP70 (pY319)/Syk (pY352), AlexaFluor488-conjugated anti-BLNK (pY84), BV421-conjugated anti-Btk (pY223)/Itk (pY180) and PE-CF594-conjugated anti-Akt (pS473) in TBS/BSA (1x/2%) for 45 min at room temperature, washed twice in 1x TBS. The acquisitions were performed on a Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analysis were carried out with FlowJo v10.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Image processing

Image processing was performed with Fiji (ImageJ) software (Schindelin et al., 2012), except when mentioned. Images shown in the figures were cropped from large fields, rotated and their contrast and brightness manually adjusted.

In vivo antigen uptake

The percentage of antigen-loaded B cells was determined by manual counting of green cells (CFSE-labeled HEL-specific B cells) having internalized at least one red microsphere, as determined by the inclusion of the red fluorescent signal within the green one in 3D-reconstructed images. Then, the distribution of the number of microspheres per B cells among antigen-loaded B cells was manually assessed per each condition.

In vitro antigen extraction

The amounts of OVA (fluorescence intensity) remaining on beads at indicated time were quantified and normalized with respect to the initial OVA fluorescence intensity (t = 0 min, 100%). Results are presented as the percentage of antigen extraction calculated as 100% - % of OVA on bead. Bar graphs show the mean ± sem.

Centrosome polarization

Centrosome polarity indexes were computed as described (Obino et al., 2016). Briefly, z stacks were projected (SUM slice) and images were manually thresholded (Default) to obtain the center of mass of the cell (CellCM). Then, the position of the centrosome and the bead geometrical center (BeadGC) were manually selected. The position of the centrosome was then projected (Centproj) on the vector defined by the CellCM–BeadGC axis. The centrosome polarity index was calculated by dividing the distance between the CellCM and the Centproj by the distance between the CellCM and the BeadGC. The index ranges from −1 (anti-polarized) to 1 (fully polarized). Results are either directly displayed as the centrosome polarity index, or as the percentage of cells with a polarized centrosome (polarity index ≥ 0.6). Boxes in boxplots extend from the 25th to 75th percentile, with a line at the median and whiskers extend from the 10th to the 90th percentile. Bar graphs show the mean ± sem.

Lysosome docking and synapse acidification

Lamp-1+-rings were manually counted. Cypher5E fluorescence signal was measured on cell-bead conjugates and normalized with respect to the mean fluorescence of beads that were not engaged in immune synapses. Bar graphs show the mean ± sem.

Statistics

All graphs and statistical analysis were performed with GraphPad Prism 7. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess normality of all datasets. Mann-Whitney test was used to determine statistical significance excepted when mentioned. Boxes in boxplots extend from the 25th to 75th percentile, with a line at the median and whiskers extend from the 10th to the 90th percentile. Bar graphs show the mean ± sem. Statistical details of experiments (sample size, replicate number, statistical significance) can be found in the figures and figure legends.

Data and Software Availability

Proteomic analysis

The complete datasets are available in the PRIDE partner repository (Vizcaíno et al., 2016) under the identification number: PXD011522 as .raw files, Proteome Discoverer 1.4 .msf files and associated pep.xml and xlsx files.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Nikon Imaging Center at CNRS-Institut Curie and PICT-IBiSA, Institut Curie (Paris, France), a member of the France-BioImaging national research infrastructure, for support in image acquisition. We gratefully thank Hélène D. Moreau for the design of the graphical abstract. D.O. was supported by fellowships from Ecole Doctorale BioSPC, Université Paris Diderot and Université Paris Descartes, and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FDT20150532056). We thank Region Ile-de-France (SESAME), Paris-Diderot University (ARS), and CNRS for funding part of the LC-MS/MS equipment. M.E. was funded by a Junior Team Leader starting grant from the Laboratory of Excellence in Research on Medication and Innovative Therapeutics (LabEx LERMIT) supported by a grant from ANR (ANR-10-LABX-33) under the program “Investissements d'Avenir” (ANR-11-IDEX-0003-01) and by an ANR @RAction starting grant (ANR-14-ACHN-0008). M.-I.Y. was supported by a research grant from FONDECYT (1141182). Funding was obtained from Association Nationale pour la Recherche (ANR-PoLyBex-12-BSV3-0014-001 to A.-M.L.-D.), the European Research Council (ERC-Strapacemi-GA 243103 to A.-M.L.-D.), ECOS (C12S02 International Research grant to M.-I.Y. and A.-M.L.-D.), and CONICYT Basal Financial Program (AFB-170005 to A.G.).

Author Contributions

D.O. designed, performed, and analyzed most of the experiments, assembled figures, and participated in manuscript writing. L.F. developed and supervised two-photon microscopy experiments. O.M. assisted with cell culture and immunofluorescences and performed biochemistry experiments. J.J.S., M.L., C.O., F.D.V.B., N.G., A.C., D.L., and F.S.-M. performed immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry experiments. C.G. and T.L. conducted the mass spectometry analysis. A.G. contributed with initial ideas, funds, reagents, and analysis tools for Galectin-8. M.E. developed and supervised mouse immunization experiments, provided SWHEL mice, and performed phospho-signaling experiments. M.-I.Y. and A.S. proposed the original hypothesis and made the preliminary observations. A.-M.L.-D. and M.-I.Y. designed and supervised the overall research, funded it, and wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: December 11, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes four figures, one table, and one video and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.052.

Contributor Information

Ana-Maria Lennon-Duménil, Email: ana-maria.lennon@curie.fr.

Maria-Isabel Yuseff, Email: myuseff@bio.puc.cl.

Supplemental Information

Score [GST], proteins identified in the GST alone control; Score [GST-Gal8], proteins identified following GST-Galectin-8 pull-down.

References

- Akkaya M., Akkaya B., Kim A.S., Miozzo P., Sohn H., Pena M., Roesler A.S., Theall B.P., Henke T., Kabat J. Toll-like receptor 9 antagonizes antibody affinity maturation. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:255–266. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0052-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anginot A., Espeli M., Chasson L., Mancini S.J., Schiff C. Galectin 1 modulates plasma cell homeostasis and regulates the humoral immune response. J. Immunol. 2013;190:5526–5533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arana E., Vehlow A., Harwood N.E., Vigorito E., Henderson R., Turner M., Tybulewicz V.L., Batista F.D. Activation of the small GTPase Rac2 via the B cell receptor regulates B cell adhesion and immunological-synapse formation. Immunity. 2008;28:88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista F.D., Iber D., Neuberger M.S. B cells acquire antigen from target cells after synapse formation. Nature. 2001;411:489–494. doi: 10.1038/35078099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boes M., Cerny J., Massol R., Op den Brouw M., Kirchhausen T., Chen J., Ploegh H.L. T-cell engagement of dendritic cells rapidly rearranges MHC class II transport. Nature. 2002;418:983–988. doi: 10.1038/nature01004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle K.B., Randow F. The role of “eat-me” signals and autophagy cargo receptors in innate immunity. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013;16:339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezski R.J., Monroe J.G. B cell antigen receptor-induced Rac1 activation and Rac1-dependent spreading are impaired in transitional immature B cells due to levels of membrane cholesterol. J. Immunol. 2007;179:4464–4472. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]