Abstract

Background:

Ongoing efforts have been made to identify new neuroimaging markers to track amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) progression. This study aimed to explore the monitoring value of multimodal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the disease progression of ALS.

Methods:

From September 2015 to March 2017, ten patients diagnosed with ALS in Peking Union Medical College Hospital completed head MRI scans at baseline and during follow-up. Multimodal MRI analyses, including gray matter (GM) volume measured by voxel-based morphometry; cerebral blood flow (CBF) evaluated by arterial spin labeling; functional connectivity, including low-frequency fluctuation (fALFF) and regional homogeneity (ReHo), measured by resting-state functional MRI; and integrity of white-matter (WM) fiber tracts evaluated by diffusion tensor imaging, were performed in these patients. Comparisons of imaging metrics were made between baseline and follow-up using paired t-test.

Results:

In the longitudinal comparisons, the brain structure (GM volume of the right precentral gyri, left postcentral gyri, and right thalami) and perfusion (CBF of the bilateral temporal poles, left precentral gyri, postcentral gyri, and right middle temporal gyri) in both motor and extramotor areas at follow-up were impaired to different extents when compared with those at baseline (all P < 0.05, false discovery rate adjusted). Functional connectivity was increased in the motor areas (fALFF of the right precentral gyri and superior frontal gyri, and ReHo of right precentral gyri) and decreased in the extramotor areas (fALFF of the bilateral middle frontal gyri and ReHo of the right precuneus and cingulate gyri) (all P < 0.001, unadjusted). No significant changes were detected in terms of brain WM measures.

Conclusion:

Multimodal MRI could be used to monitor short-term brain changes in ALS patients.

Keywords: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, Disease Progression, Monitoring Value, Multimodal Magnetic Resonance Imaging

摘要

背景:

探索多模态磁共振成像对肌萎缩侧索硬化(ALS)病情进展的监测价值。

方法:

2015年9 月至2017 年3 月,于北京协和医院神经科诊断的10例ALS患者完成了基线及随访的磁共振扫描,多模态分析技 术包括基于体素的形态学分析测量灰质体积、动脉自旋标记评价脑血流量、静息态功能磁共振成像测定功能连接性(包括分 数低频振幅与局部一致性)及弥散张量成像评价脑白质纤维束完整性。应用配对t检验对随访与基线的影像学数据进行对比。

结果:

在纵向比较中,ALS患者6月后的运动区与运动外区域的脑结构(右侧中央前回、左侧中央后回与右侧丘脑的灰质体积) 及血流灌注(双侧颞极、左侧中央前回、中央后回与右侧颞中回的脑血流量)均较基线时有不同程度的进一步损害(所有均 P<0.05,经错误发现率校正)。运动区(右侧中央前回与额上回的分数低频振幅,右侧中央前回的局部一致性)的功能连 接性较基线显著增加,运动区外(双侧额中回的分数低频振幅,右侧楔前叶与扣带回的局部一致性)的功能连接性较基线显 著降低(所有均P<0.001,未校正)。患者随访时全脑的白质相关指标较基线无显著改变。

结论:

多模态磁共振技术可用于监测短期内ALS患者的脑内变化。

INTRODUCTION

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a rapidly progressive neurodegenerative disease, characterized by the involvement of both upper motor neurons (UMNs) and lower motor neurons (LMNs). The pathogenesis of ALS is not yet fully understood and no effective cure is available.[1] It has been noted that the clinical manifestations and speed of disease progression greatly vary among ALS patients, and several indicators have been applied to disease progression monitoring as well as treatment efficacy evaluation in clinical studies, including the revised ALS functional rating scale (ALSFRS-R) score, forced vital capacity, muscle strength, and survival time.[2] However, the functional changes and survival time only partially reflect the disease progression or treatment efficacy; thus, investigation for a more objective and efficacious biomarker is still ongoing. A sensitive indicator will be able to help reduce the sample size in the preliminary experiment, provide a more accurate evaluation of the sample size for Phase III clinical trials, and better define different clinical subtypes that require separate assessment.[3]

Various biochemical substances in body fluids (neurofilaments, tau protein, inflammatory factors, etc.) have been used as biomarkers for ALS progression monitoring;[4] meanwhile, neural electrophysiological techniques[5] and neuroimaging[6] are also commonly adopted. Among these measures, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been recognized as a promising tool with its noninvasiveness, easy accessibility, repeatability, and increasing sensitivity.[7] Multimodal MRI adopts various sequence and analysis methods, such as voxel-based morphometry (VBM), arterial spin labeling (ASL), resting-state functional MRI (RS-fMRI), and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI). With the help of multimodal MRI, it has been demonstrated that the motor cortex and the extramotor areas are extensively impaired in ALS patients, and ongoing efforts have been made to identify new neuroimaging markers to track ALS progression.[8] This study explored the significance of multimodal MRI in disease monitoring by longitudinal follow-up in ten ALS patients.

METHODS

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) (No. S-619). All patients had been fully informed of the purpose and methods of the present study and provided written informed consent from themselves or their guardians.

Subjects

From September 2015 to March 2017, ten patients registered in the ALS cohort of PUMCH with normal cognition agreed to undergo MRI scans and were enrolled in this study. The methods adopted for cognition evaluation were published in our previous article.[9] All patients had head MRI scans at baseline and 6 months later after recruitment. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Familial ALS patients; (2) patients with a history of other neurological diseases; and (3) patients with substance abuse, severe depression, anxiety, or other mental problems.

Image acquisition

Images were acquired on a 3.0 T magnetic resonance system (Discovery MR 750, GE) with an 8-channel phase array head coil. All patients were required to be alert, close their eyes, remain supine, and avoid any conscious thinking. The structural images of the whole brain were scanned by a three-dimensional (3D) fast spoiled gradient echo sequence: repetition time (TR) = 8.2 ms, echo time (TE) = 3.2 ms, matrix = 256 × 256, field of view (FOV) =25.6 cm × 25.6 cm, slice thickness = 1.0 mm, no slice gap, and a total of 180 slices. Images of 3D pseudocontinuous ASL were collected using the following protocol: TR = 4886 ms, TE = 11 ms, FOV 24 cm × 24 cm, image reconstruction matrix = 128 × 128, slice thickness = 4 mm, no slice gap, postlabel delay = 2025 ms, FOV = 24 cm, and a total of 40 slices. The RS-fMRI images were obtained using an echo-planar imaging sequence with the following parameters: TR = 2000 ms, TE = 30 ms, FOV = 24 cm × 24 cm, matrix = 64 × 64, slice thickness = 4 mm, no slice gap, and a total of 36 slices and 200 phases. The T1-weighted images were simultaneously performed with ASL and RS-fMRI. For DTI analyses, we used a spin echo sequence: TR = 6000 ms, TE = the minimal default value, FOV = 24 cm × 24 cm, matrix = 128 × 128, b = 0 and 1000 s/mm2, slice thickness = 3 mm, no slice gap, 15 gradient directions, and a total of 50 slices.

Image preprocessing

The 3D structural images of the whole brain and the ASL sequences were preprocessed to obtain the graphs of gray matter (GM) and cerebral blood flow (CBF) for further analysis by SPM12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/) in Matlab2013b (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). The detailed procedures are described in our previous article.[9] The RS-fMRI images were preprocessed by SPM12 and DPABI 2.3 (http://rfmri.org/dpabi)[10] in Matlab2013b so that the graphs of fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (fALFF) and regional homogeneity (ReHo) were derived. The DTI images were preprocessed by FSL (https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki) and PANDA 1.3.1 (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/panda)[11] for the graphs of fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD).

Statistical analysis

SPSS software version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the analysis of demographic and clinical data. The continuous variables that were normally distributed were presented with the mean ± standard deviation, while those that did not follow a normal distribution were shown by median (range). The paired t-test was carried out in the comparison of the data between baseline and the 6th month of follow-up, and P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. For imaging data, a paired t-test was conducted between the imaging data at baseline and at the 6th month by SPM12 (https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12/) and DPABI 2.3 (http://rfmri.org/dpabi) in Matlab2013b (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). P < 0.05 after false discovery rate (FDR) correction was recognized as statistically significant. If no voxel survived after FDR correction, a liberal P < 0.001 without correction was considered as statistically significant instead. Only the clusters of over 100 voxels were reported, and the results were visualized by Brant toolbox 2.0 (http://brant.brainnetome.org/en/latest/).

RESULTS

The mean age of the ten patients enrolled was 47.9 ± 9.2 years. The mean time from symptom onset to diagnosis of ALS was 10 months (range: 8–20 months). The average baseline ALSFRS-R score was 43.3 ± 2.0, which was significantly higher than that at 6 months (38.5 ± 1.7, P = 0.038). The demographic and clinical characteristics of each patient are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the ten patients with ALS

| No. | Age at baseline (years) | Gender | Onset type | Disease duration (months) | Diagnosis level | ALSFRS-R score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 months later | ||||||

| 1 | 51 | Male | Limbs | 10 | Laboratory supported | 43 | 40 |

| 2 | 46 | Male | Bulbar | 10 | Laboratory supported | 44 | 38 |

| 3 | 44 | Female | Limbs | 16 | Laboratory supported | 40 | 38 |

| 4 | 37 | Male | Limbs | 12 | Clinically probable | 42 | 35 |

| 5 | 50 | Male | Limbs | 9 | Clinically probable | 47 | 41 |

| 6 | 52 | Female | Limbs | 8 | Clinically probable | 45 | 39 |

| 7 | 47 | Female | Limbs | 13 | Clinically definite | 39 | 37 |

| 8 | 32 | Male | Limbs | 16 | Laboratory supported | 45 | 40 |

| 9 | 65 | Female | Bulbar | 9 | Clinically probable | 44 | 38 |

| 10 | 55 | Male | Bulbar | 20 | Clinically probable | 44 | 39 |

ALSFRS-R: The revised ALS functional rating scale; ALS: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

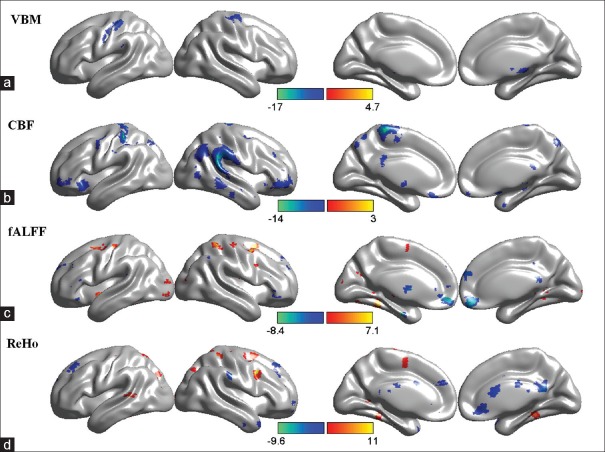

In the VBM study, the GM volume of the right precentral gyri, the left postcentral gyri, and the right thalami in ALS patients at the 6th month of follow-up was significantly lower than that of their baselines [P < 0.05, FDR corrected; Figure 1a and Table 2 – VBM].

Figure 1.

The comparison of multimodal magnetic resonance imaging metrics between baseline and the 6th month of follow-up. (a) The regions with decreased volume of gray matter at follow-up. (b) The regions with decreased cerebral blood flow at follow-up. (c) The regions with altered functional connectivity, including low-frequency fluctuation at follow-up. (d) The regions with altered regional homogeneity at follow-up. The warm colors indicate increases and the cold colors indicate decreases. The colored bars in a-d represent the t value. P value in a and b was <0.05 with false discovery rate correction, while that in c and d was <0.001 without correction. VBM: Voxel-based morphometry; CBF: Cerebral blood flow; fALFF: Fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation; ReHo: Regional homogeneity.

Table 2.

The clusters with altered imaging metrics between baseline and follow-up

| No. | Voxel size | Brodmann area | MNI coordinates of the extrema | t | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | ||||

| VBM | ||||||

| 1 | 508 | BA4_L | −38 | −27 | 57 | −12.71 |

| 2 | 410 | BA6_R | 29 | −17 | 57 | −9.21 |

| 3 | 364 | NA | 12 | −23 | −5 | −16.77 |

| 4 | 225 | BA6_R | 56 | −8 | 51 | −7.49 |

| CBF | ||||||

| 1 | 629 | BA3_L | −20 | −36 | 62 | −14.33 |

| 2 | 288 | BA4_L | −7 | −28 | 66 | −8.70 |

| 3 | 268 | BA38_R | 42 | 26 | −22 | −13.98 |

| 4 | 126 | BA47_L | −38 | 54 | −4 | −6.81 |

| 5 | 122 | BA48_L | −30 | 14 | −8 | −8.60 |

| fALFF | ||||||

| 1 | 122 | BA11_R | 9 | 42 | −15 | −6.96 |

| 2 | 171 | BA6_R | 38 | 0 | 50 | 7.44 |

| 3 | 129 | BA6_R | 24 | −13 | 54 | 7.45 |

| ReHo | ||||||

| 1 | 101 | BA6_R | 40 | 4 | 37 | 10.22 |

| 2 | 208 | BA30_R | 7 | −51 | 18 | −5.76 |

MNI: Montreal Neurological Institute; VBM: Voxel-based morphometry; CBF: Cerebral blood flow; fALFF: Fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation; ReHo: Regional homogeneity; NA: Not available.

In the ASL study, the CBF of bilateral temporal poles, left precentral gyri, postcentral gyri, and right middle temporal gyri at 6 months of follow-up was significantly lower than those of the baselines in ALS patients [P < 0.05, FDR corrected; Figure 1b and Table 2– CBF].

In the RS-fMRI study, no voxel survived in the fALFF and ReHo analysis after FDR correction (P < 0.05). With an uncorrected P < 0.001, the fALFF of right precentral gyri and superior frontal gyri increased during follow-up compared with baseline, while that of the bilateral middle frontal gyri significantly declined [Figure 1c and Table 2 – fALFF]. The ReHo of the right precentral gyri significantly increased 6 months later, whereas that of the right precuneus and cingulate gyri decreased [P < 0.001 uncorrected; Figure 1d and Table 2 – ReHo].

In the DTI study, no significant difference was observed between the baseline and follow-up in terms of FA and MD in the whole brain at the set statistical threshold (P < 0.001 uncorrected).

DISCUSSION

We compared the head multimodal MRI images of ten ALS patients at baseline and 6 months of follow-up in the present study. The GM volume and CBF significantly decreased at 6 months compared to baseline after corrections for multiple comparisons. Under a more liberal voxel-wise threshold of P < 0.001 uncorrected, the fMRI data showed several sporadic clusters with altered metrics during follow-up, and FA and MD of the whole brain remained unchanged.

The GM volume of the patients’ right precentral gyri, left postcentral gyri, and right thalami significantly decreased compared to their baseline level, which was consistent with the results of previous longitudinal VBM studies that reported significant GM loss in the bilateral precentral gyri, left postcentral gyri, motor cortices, frontal areas, and bilateral frontotemporal lobes.[12,13] As with most studies,[14,15,16,17] no significant change in FA and MD was revealed in our study. Such observation could be explained by the “floor effect,” which suggests that the impairment of white-matter (WM) fiber tracts was so severe at baseline that longitudinal alteration was not noticeable. Meanwhile, our previous cross-sectional study demonstrated that the GM volume of the whole brain did not significantly differ between ALS patients and healthy controls (HCs),[9] though FA in the bilateral corticospinal tract and corpus callosum was significantly lower in the ALS group than in the HC group,[18] indicating that the microstructural involvement of WM was more prominent than GM damage in ALS patients at baseline. Such findings lend further support to the existence of the floor effect.

We adopted ASL to assess the longitudinal changes of CBF in ALS patients and found that the CBF in multiple areas was significantly lower at follow-up than at baseline. The hypoperfusion in motor areas was expected and consistent with the GM loss there. Additionally, hypoperfusion in extramotor areas such as bilateral frontal poles and right temporal lobes was also noted. According to research that evaluated the CBF of ALS patients compared with that of HCs at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year using computed tomographic perfusion scanning, no significant difference was observed.[19] However, the mean transit time of the temporal lobe at the 6th month was significantly longer in the ALS group, and such difference expanded to whole-brain cortices at 1 year of follow-up, which added evidence to abnormal perfusion in extramotor areas in ALS patients, though longitudinal comparison was absent in that research.[19]

Based on the longitudinal comparison of RS-fMRI, functional connectivity (FC) increased in the motor areas and decreased in the extramotor areas of ALS patients. The enhancement of FC in the motor areas could be compensatory for structural damage, though such compensation would be exhausted with increasing disease burden; it could be associated with the loss of cortical inhibitory neurons and pathological alteration in local inhibitory circuits, as well.[20] The reduced FC of the frontal lobes and cingulate gyri implied that extramotor areas were also involved in ALS; as the cognitive and emotional functions of these areas are not redundant as those of motor pathways, compensation is not feasible, and thus, decreased FC was observed instead.[20]

Previous studies have compared different imaging techniques in the longitudinal monitoring of ALS patients, and the conclusions were inconsistent. Two studies reported declined FA in the corticospinal tract[21] and increased MD in the corpus callosum,[22] respectively, with insignificant changes in the cortical GM. One study demonstrated thinner bilateral precentral cortices and reduced GM volume, while changes in FA and MD in the corticospinal tract were not noticeable.[15] Some studies, however, indicated that both GM and WM had significant alterations in ALS.[12] As stated by a previous research, the WM damage was more remarkable than the GM damage at baseline, presenting as impairment in the corticospinal tract and corpus callosum and GM loss in left motor cortices and temporal areas; however, alterations in the GM turned out to be more prominent during follow-up.[13] This is consistent with our results, which suggest that ALS might feature WM involvement at the initial stage and develop extensive cortical degeneration gradually. It should be noted that CBF decreases were recorded in some extramotor areas such as the frontotemporal lobes, even though no substantial GM alterations occurred. This implied that hypoperfusion in certain regions might take place prior to GM atrophy in the progression of ALS. The FC changes in the temporal poles, cingulate gyri, etc., were also independent of GM involvement. Nevertheless, these results did not survive multiple comparisons and thus should be interpreted with caution.

There are some intrinsic limitations to neuroimaging in monitoring the progression of ALS. The clinical manifestations and functional outcomes of ALS patients were a comprehensive reflection of UMN, LMN, and extramotor area involvement; however, the complexity of the phenotypes lies not only in the damage of the multisegmental neuraxis, but also in the dynamic changes to the extensively engaged neural network and multiple compensatory mechanisms.[23] ALSFRS-R is the only validated clinical indicator for the evaluation of disability in ALS patients, but the absolute ALSFRS-R scores upon diagnosis are highly variable and thereafter decline at varying but relatively stable rates.[24] Therefore, patients who undergo MRI with the same ALSFRS-R score at a given time might have been in different stages of disease and might progress variably. Furthermore, ALSFRS-R has low sensitivity in identifying functional impairment of the frontal lobe. ALSFRS-R is also more sensitive to LMN symptoms than UMN symptoms; thus, the UMN-related manifestations might be underestimated with progressive loss in the LMN. On the other hand, neuroimaging techniques could assess the involvement of only UMN and extramotor areas in ALS patients, while the impairment of LMN and the complicated interactions between the two types of neurons are beyond measure. Even when we limited our evaluation target to the neurological compromise of the UMN and extramotor regions, similar clinical or functional outcomes may result from heterogeneous damage to the WM and GM. In summary, the gap between imaging metrics and clinical condition is predicted. There were also a few limitations to the present study. First, the sample size was small; thus, subgroup categorization by clinical phenotypes was not viable and population homogeneity was not assured. Second, only two time points were assessed; therefore, it was not clear whether the longitudinal changes were linear or nonlinear. In addition, more frequent evaluation could reduce false-positive errors. Hence, combined assessment of the UMN and LMN by multimodal head MRI, spinal MRI, and neural electrophysiologic techniques in a larger sample of ALS patients with different clinical phenotypes at multiple periods may yield more reliable results.

In conclusion, multimodal MRI could be applied to monitor short-term intracranial alterations in ALS patients. GM loss in motor cortices might be a more sensitive measure of disease progression than damage in the corticospinal tract. Hypoperfusion in extramotor areas and decreased FC might take place in advance of detectable structural changes.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was funded by a grant of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (No. 2016-I2M-1-004).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Yuan-Yuan Ji

REFERENCES

- 1.Swinnen B, Robberecht W. The phenotypic variability of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:661–70. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.184. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berry JD, Miller R, Moore DH, Cudkowicz ME, van den Berg LH, Kerr DA, et al. The combined assessment of function and survival (CAFS): A new endpoint for ALS clinical trials. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2013;14:162–8. doi: 10.3109/21678421.2012.762930. doi: 10.3109/21678421.2012.762930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grolez G, Moreau C, Danel-Brunaud V, Delmaire C, Lopes R, Pradat PF, et al. The value of magnetic resonance imaging as a biomarker for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:155. doi: 10.1186/s12883-016-0672-6. doi: 10.1186/s12883-016-0672-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarasiuk J, Kułakowska A, Drozdowski W, Kornhuber J, Lewczuk P. CSF markers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2012;119:747–57. doi: 10.1007/s00702-012-0806-y. doi: 10.1007/s00702-012-0806-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fathi D, Mohammadi B, Dengler R, Böselt S, Petri S, Kollewe K, et al. Lower motor neuron involvement in ALS assessed by motor unit number index (MUNIX): Long-term changes and reproducibility. Clin Neurophysiol. 2016;127:1984–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2015.12.023. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2015.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner MR, Grosskreutz J, Kassubek J, Abrahams S, Agosta F, Benatar M, et al. Towards a neuroimaging biomarker for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:400–3. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70049-7. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filippi M, Agosta F, Abrahams S, Fazekas F, Grosskreutz J, Kalra S, et al. EFNS guidelines on the use of neuroimaging in the management of motor neuron diseases. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:526–e20. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02951.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiò A, Pagani M, Agosta F, Calvo A, Cistaro A, Filippi M, et al. Neuroimaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Insights into structural and functional changes. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:1228–40. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70167-X. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70167-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen D, Hou B, Xu Y, Cui B, Peng P, Li X, et al. Brain structural and perfusion signature of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with varying levels of cognitive deficit. Front Neurol. 2018;9:364. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00364. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan CG, Wang XD, Zuo XN, Zang YF. DPABI: Data processing and analysis for (Resting-state) brain imaging. Neuroinformatics. 2016;14:339–51. doi: 10.1007/s12021-016-9299-4. doi: 10.1007/s12021-016-9299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cui Z, Zhong S, Xu P, He Y, Gong G. PANDA: A pipeline toolbox for analyzing brain diffusion images. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:42. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00042. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Senda J, Kato S, Kaga T, Ito M, Atsuta N, Nakamura T, et al. Progressive and widespread brain damage in ALS: MRI voxel-based morphometry and diffusion tensor imaging study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2011;12:59–69. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2010.517850. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2010.517850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menke RA, Körner S, Filippini N, Douaud G, Knight S, Talbot K, et al. Widespread grey matter pathology dominates the longitudinal cerebral MRI and clinical landscape of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2014;137:2546–55. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu162. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinbach R, Loewe K, Kaufmann J, Machts J, Kollewe K, Petri S, et al. Structural hallmarks of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis progression revealed by probabilistic fiber tractography. J Neurol. 2015;262:2257–70. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7841-1. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7841-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwan JY, Meoded A, Danielian LE, Wu T, Floeter MK. Structural imaging differences and longitudinal changes in primary lateral sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroimage Clin. 2012;2:151–60. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2012.12.003. doi: doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agosta F, Rocca MA, Valsasina P, Sala S, Caputo D, Perini M, et al. Alongitudinal diffusion tensor MRI study of the cervical cord and brain in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:53–5. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.154252. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.154252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blain CR, Williams VC, Johnston C, Stanton BR, Ganesalingam J, Jarosz JM, et al. A longitudinal study of diffusion tensor MRI in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2007;8:348–55. doi: 10.1080/17482960701548139. doi: 10.1080/17482960701548139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou B, Shen D, Cui B, Li X, Peng P, Tai H, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging studies of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients with various levels of cognitive impairment (in Chinese) Chin J Neurol. 2018;51:598–605. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1006-7876.2018.08.008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy MJ, Grace GM, Tartaglia MC, Orange JB, Chen X, Rowe A, et al. Widespread cerebral haemodynamics disturbances occur early in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2012;13:202–9. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2011.625569. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2011.625569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen D, Cui L, Cui B, Fang J, Li D, Ma J, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the functional MRI investigation of motor neuron disease. Front Neurol. 2015;6:246. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00246. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cardenas-Blanco A, Machts J, Acosta-Cabronero J, Kaufmann J, Abdulla S, Kollewe K, et al. Structural and diffusion imaging versus clinical assessment to monitor amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroimage Clin. 2016;11:408–14. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.03.011. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Albuquerque M, Branco LM, Rezende TJ, de Andrade HM, Nucci A, França MC., Jr Longitudinal evaluation of cerebral and spinal cord damage in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;14:269–76. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.01.024. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt R, Verstraete E, de Reus MA, Veldink JH, van den Berg LH, van den Heuvel MP, et al. Correlation between structural and functional connectivity impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35:4386–95. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22481. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verstraete E, Turner MR, Grosskreutz J, Filippi M, Benatar M attendees of the 4th NiSALS meeting. Mind the gap: The mismatch between clinical and imaging metrics in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2015;16:524–9. doi: 10.3109/21678421.2015.1051989. doi: 10.3109/21678421.2015.1051989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]