Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Adverse drug reaction (ADR) is a public health problem which constitutes one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In India, only a few studies reported cancer chemotherapy-induced ADRs. The objectives of the present study were to assess the organ system involved, frequency, severity, and preventability of the ADRs occurred.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Data on ADRs of retrospective cohorts were extracted from the filled ADR forms received from the department of radiation oncology. Descriptive statistic was used to summarize and analyze the available data, namely patient demography, causality, severity, and preventability of the event.

RESULTS:

A total of 191 chemotherapy-induced ADR reports were received from 164 patients during the period March 2015 to August 2017. Almost three-fourth of the ADRs occurred in patients who were receiving regimens involving multiple drugs. Taxanes, alkylating agents, and platinum compounds were the common drug groups involved. The skin (n = 90) was the most frequently involved organ with alopecia and hyperpigmentation as most common manifestations. The severity (Hartwig and Siegel) and preventability scales (Modified Schumock and Thornton) indicated that most reactions were mild (54.45%) in nature and the majority of them were preventable. More than two-third (69%) of the reactions were related “possible” to the suspected drug as determined by the World Health Organization causality assessment.

CONCLUSION:

Chemotherapy-related ADRs among cancer patients are worrisome. It has a negative impact on patient quality of life and in addition increases cost of therapy. It is found that timely reporting of chemotherapy-related ADRs and having an effective ADR monitoring system in place ensure preventability of the ADRs in many cases. Oncologists, Radiotherapists and Onco-surgeons should be actively involved in ADR reporting (Onco-Pharmacovigilance) and exchange constructive information, update and educate each other about appropriate use of anticancer drugs. Onco-pharmacovigilance is the need of the hour and could be of immense value in reducing morbidity and mortality if practiced with utmost importance.

Keywords: Adverse drug reactions, chemotherapy, onco-pharmacovigilance, preventability, severity

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines adverse drug reaction (ADR) as “A response to a drug, which is noxious and unintended, and which occurs at doses normally used in man for the prophylaxis, diagnosis, or therapy of disease, or for the modifications of physiological function.”[1] It has been demonstrated by a number of studies that drug-induced morbidity and mortality is one of the major health problems in our country.[2,3] The Pharmacovigilance Programme of India (PvPI) is an initiative to address this issue. Activities under PvPI include collection, reporting, and follow-up of ADRs occurring in patients. The PvPI collate the data received from various Adverse Drug Reaction Monitoring Centers (AMCs) in the country and submit them on regular basis to global database maintained at Uppsala, Sweden. The signals generated from such activities are used to recommend regulatory interventions in the form of banning a drug, labeling revisions besides communicating risks to health-care professionals and the public. The ultimate of PvPI is to identify, characterize, and estimate the extent of the problem associated with drug use in the country.

Cancer is one of the three leading causes of death in the modern world.[4] It is estimated to cause 12% death annually worldwide.[5] The incidence of cancer is about 70–90/100,000 persons, and prevalence is estimated approximately 2.5 million in India.[5] Cancer chemotherapy has improved drastically over a past few decades. Chemotherapy is now employed as a multimodal approach for treatment of different malignancies and has been revolutionized with the discovery of newer drugs for curative treatment for certain fatal malignancies.[6]

Antineoplastic agents can damage normal cells along with cancerous cell and have narrow therapeutic index.[7] Patients on chemotherapy are vulnerable to ADRs as they receive multiple drugs as a part of the anticancer regimen. Complications secondary to chemotherapy include an increase in morbidity and mortality.[8] The patients after undergoing chemotherapy have a general sense of low feeling, have restricted mobility due to the aggravated physical discomfort, spend more time on bed, have low sexual desire, reduce interaction with society, and have less working capabilities.[9] In other words, the application of chemotherapy regimens and its courses increase the unwanted toxic side effects which gradually aggravate the quality of life of the patients as mentioned in Ma et al.[10] Thus, an active drug surveillance system is needed to capture drug-related risk information in cancer patients. The aim of the study was to determine the nature and severity of ADRs in cancer patients based on ADRs received from the department of radiation oncology. All these ADRs were reported to AMC established under PvPI at All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India.

Materials and Methods

AIIMS, Jodhpur, is an Institute of National Importance established under Pradhan Mantri Swasthya Suraksha Yojana and still is in establishing stage. However, AMC was established since the inception of outpatient services. The ADRs received from March 2015 to August 2017 were compiled and discussed here. It was a retrospective cohort study, and the data were extracted from the filled ADR forms received by AMC. The same ADR information was also entered in “VigiFlow” software for reporting to the National Coordinating Center (NCC). The collected data were later summarized and were used to determine the nature and severity of ADRs. AMC is actively involved not only in collecting ADR data from the hospital but also spreading awareness about the need and importance of pharmacovigilance. This is achieved by sending weekly reminder e-mails, regular sharing of drug safety alerts, newsletter, other advertising materials, running animations on television (TV) panels in inpatient department (IPD) and outpatient department (OPD) areas, prescription sheets including patient-centered message emphasizing the need for reporting ADR, distributing pamphlets, and sensitization sessions to health-care professionals (HCPs) and paramedical staff. The ADR (version 1.2) form is a simplified version of the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization[11] adopted by the center to facilitate reporting by the HCPs. The HCPs either fill the ADR forms themselves or inform the AMC telephonically. In addition, the Patient Safety Pharmacovigilance Associate makes a regular visit to OPD and IPD. The collected individual case safety report was analyzed for patient demography, causality, severity, and preventability of the event. All ADRs were submitted to NCC through “VigiFlow” software. ADRs were classified on the basis of Anatomical and Therapeutic Classification System (1999).[12] Causality assessment of ADRs was done by causality assessment scale proposed by the WHO Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring–the Uppsala Monitoring Centre[13] which classifies suspected ADRs as certain, probable, possible, unlikely, conditional/unclassified, and unassessable/unclassifiable. The severity of the ADRs was assessed by Modified Hartwig and Siegel Scale[14] which gives an impression of the severity of ADRs and tags it as mild, moderate, or severe. Preventability of the ADRs was assessed by Modified Schumock and Thornton Scale.[15] This scale of preventability classifies ADRs as definitely preventable, probably preventable, and not preventable. Descriptive statistic was used to summarize and analyze the available data on nature and the frequency of various ADRs.

Results

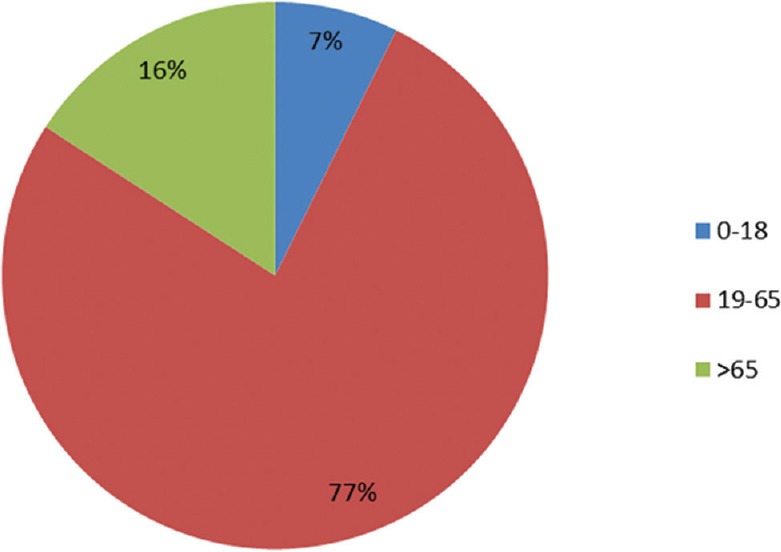

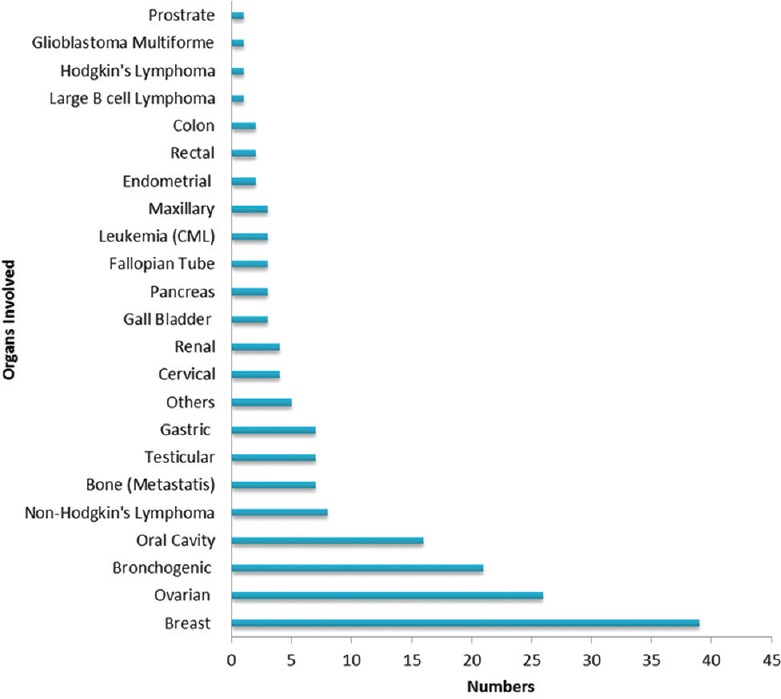

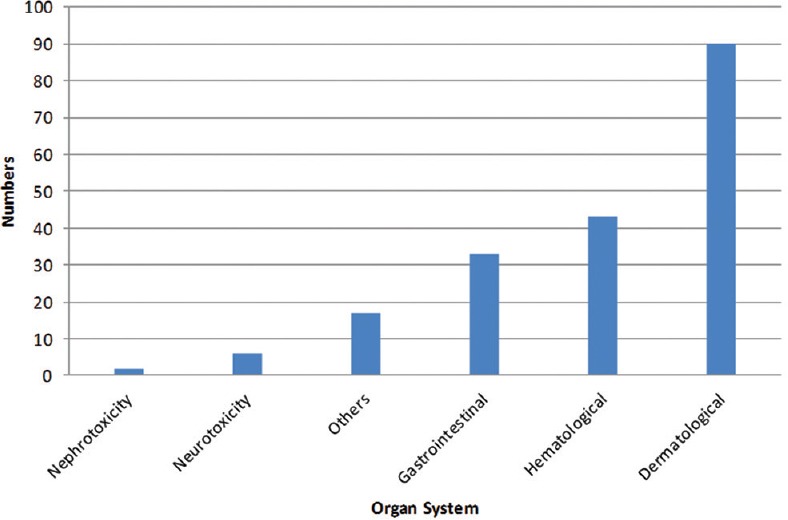

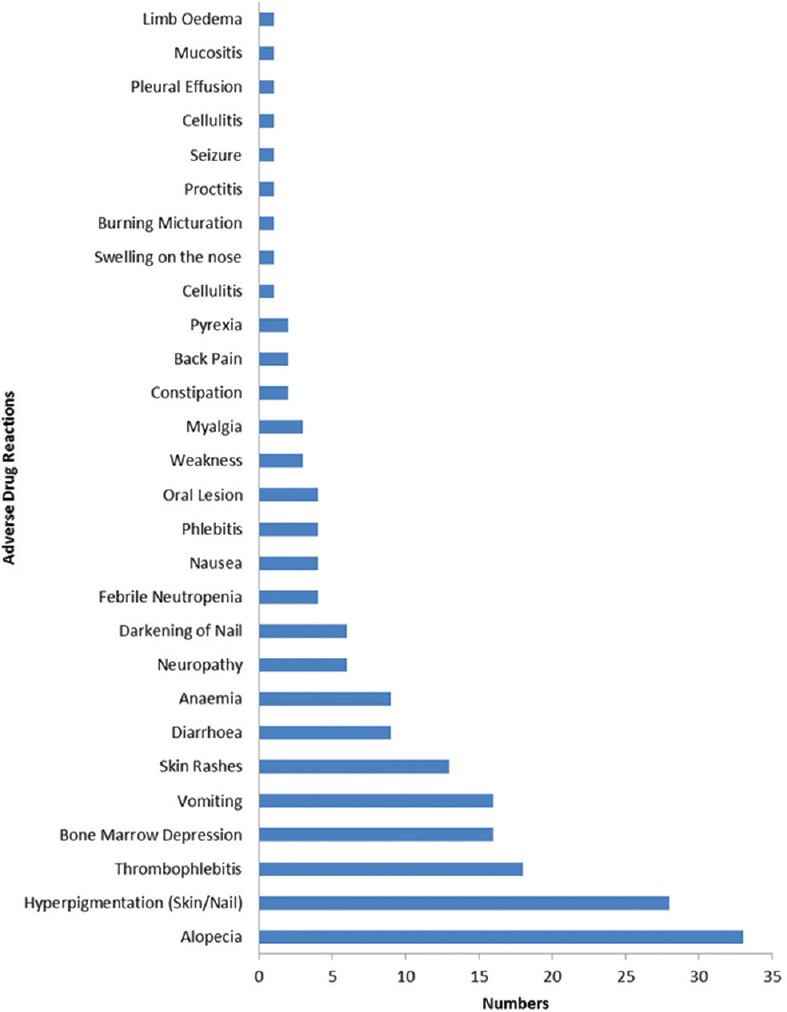

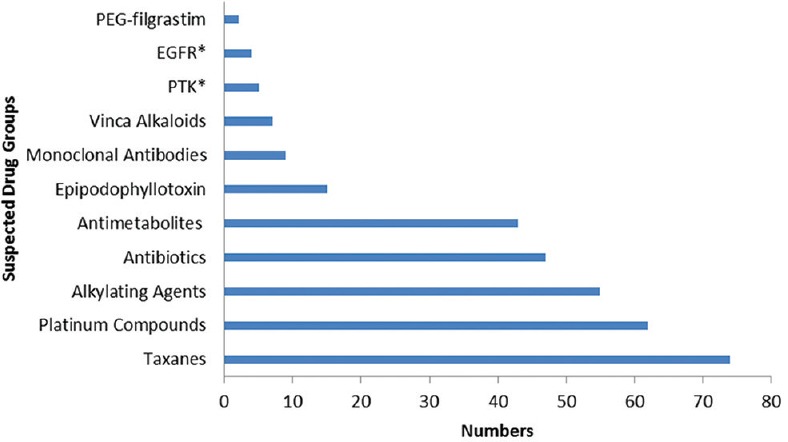

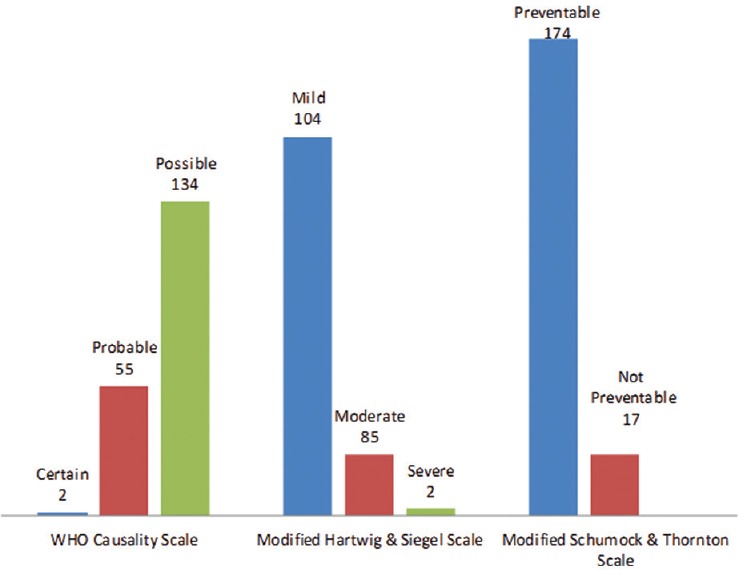

A total of 191 chemotherapy-induced ADRs from 164 patients were received by AMC until August 2017. The majority of ADRs occurred in the age group of 19–65 years (n = 126, 77%) with a female preponderance (n = 88, 54%) [Figure 1]. In some patients, more than one ADR was observed. Monotherapy constitutes only 50 (26%) drug reactions, while 141 (74%) reactions were from those who received these drugs as a part of a multidrug regimen. The various indications for the use of chemotherapy were tumors of the breast, lung, ovary, oral cavity, lymphoma, and other malignancies [Figure 2]. The observations revealed that skin as an organ was involved in almost half of the total ADRs reported followed by hematological (n = 43; 23%), gastrointestinal (n = 33; 17%), renal, nervous, and other systems (n = 25; 13%) [Figure 3]. Alopecia, hyperpigmentation of the skin and nail, thrombophlebitis, bone marrow depression, neuropathy, and vomiting were among the common reactions observed [Figure 4]. Docetaxel, carboplatin, cisplatin, and cyclophosphamide were the most common drugs involved in ADRs in the study population [Figure 5]. Most reactions were mild (54.45%) in nature and the remainder being moderate (44.50%) and severe (1.04%) as assessed by Modified Hartwig and Siegel Scale. There were a total of 45 (including one death) serious adverse events that required hospitalization or caused prolongation of existing hospitalization due to either intractable vomiting, electrolyte imbalance, blood transfusion secondary to anemia, or febrile neutropenia. Assessment by Modified Schumock and Thornton Scale of ADR preventability showed that most of the ADRs belonged to the category of “preventable” (n = 174). The majority of the reactions were related “possible” (more than two-third) to drugs as determined by causality assessment [Figure 6].

Figure 1.

Distribution of adverse drug reactions according to the age (years)

Figure 2.

Distribution of types of malignancy in the study population (n = 124)

Figure 3.

Frequency of adverse drug reactions based on the organ system involved

Figure 4.

Type with frequency of adverse drug reactions

Figure 5.

Suspected drugs involving in causing adverse drug reactions. *EGFR inhibitors = Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, PTK = Protein tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Figure 6.

Causality, severity, and preventability assessment

Discussion

ADRs due to cancer chemotherapy are quite challenging as it impacts the quality of life of patients and also to the providers who manage such cases.[16] Chemotherapy-related ADRs increase mortality rate as well as escalate the cost of the therapy.[17] In India, the scenario is worse as compared to developed countries as only 1% of global data of ADRs due to cancer chemotherapy is reported in India.[18,19] In our country, due to the low ratio of doctor to patient, most of the events are not reported citing many reasons, i.e., lack of time, low motivation, ignorance, and lethargy. In spite of having trained medical professional in our country, sometimes doctors are hesitant to report because they fear litigation and think that ADR reporting might go against them. Ignorance on the part of the HCPs regarding how to report and no awareness about onco-pharmacovigilance could have contributed to underreporting.[20,21]

In our study, we found that majority of the ADRs occurred in females[22] and increased incidence in female patients might be due to hormonal changes occurring during different stages of life that might cause an alteration in the pharmacokinetic profile of the drugs.[23] Majority of the ADRs occurred in the age group of 19–65 years, which is similar to Astolfi et al.[24] Our findings also showed that most of the ADRs (29.8%) were seen in the age group of 51–60 years as most patients belonged to this age group which is consistent with results of other studies.[25,26] The metabolizing capacity and the excretory functions are generally diminished as a person ages and there are also pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic alterations of drugs in the body and thus increasing the chances of ADRs.[27]

In our study, most common cancers that had been treated in our setup were breast cancer (n = 39; 23.07%) followed by ovarian (n = 26; 15.38%), bronchogenic (n = 21; 12.42%), and oral cavity cancer (n = 16; 9.46%) very similar to reported earlier.[25] As a whole, Indian data on cancer indicate that the most common cancer among males is oropharyngeal and in females is cervical.[28] The variation in type that we have observed [Figure 2] could be due to the geographical location, dietary habits, and lifestyle.[29] However, this needs to be further explored in a different study.

ADRs occurring only due to chemotherapy were taken into consideration. The most common drugs causing ADRs were docetaxel (14.2%), carboplatin (11.9%), cisplatin (11.5%), paclitaxel (9.2%), and cyclophosphamide (8.8%). Results of the present analysis are in accordance with reports from a similar study.[26] In our study, microtubule-damaging drugs account for most of the ADRs as they were most prescribed in a proportionately higher ratio of females which was similar to Astolfi et al.[24]

Among the reported ADRs, common ones were alopecia (17.27%), hyperpigmentation of the skin and nail (14.65%), thrombophlebitis (9.42%), bone marrow depression (8.37%), vomiting (8.376%), and diarrhea (4.71%). The findings were quite similar to a study by Saini et al.[1] Other ADRs experienced by the patients were nausea, burning micturition, constipation, skin rash, and others. Our study is in contrast to studies carried out by Mallik et al. which had neutropenia as the most common ADR, while Lau et al. reported constipation to be the most common ADR.[30,31] In our opinion, this difference could be due to either more frequent use of drugs that have bone marrow suppressing effects in one study or overuse of opioid to control intractable pain in many malignancies in another.

In this study, only ADRs were taken into account which occurs due to chemotherapy. Our study has assessed three different parameters of an ADR, namely the causality, severity, and preventability due to the different management plans adopted on the basis of the stage of cancer, cost of the management, and patient-related factors, thus providing basic information regarding the safety profile of anticancer drugs. The WHO causality assessment scale indicated that 70% of the reactions were “possible,” which is similar to another onco-pharmacovigilance study.[32] As anticancer regimens usually include multiple drugs and the explanation, we propose that the other drugs in the regimen might contribute to the reaction observed. Furthermore, it cannot be completely ruled out that sign and symptoms of the disease may sometimes simulate as an ADR in these terminally ill patients. Moreover, information with regard to drug withdrawal secondary to the adverse reaction lack in the majority as ADRs are quite common with such drugs and withdrawal is usually rare in such cases. On the severity scale, most of the reactions were of mild grades which do not warrant stopping or changing of the drug. Preventability scales showed that majority of the ADRs were preventable.

An important limitation of the study is that the re-challenge test was not done in any case due to medical and ethical issues that are the reason behind labeling only two reactions as being “certain.” As it was a retrospective study, there are chances of underreporting and incomplete documentation of ADRs data, particularly from initial few reports. We expect that in the near future, the reporting of ADRs will further improve subsequent to the increase in faculty strength of the department.

Conclusion

We may conclude that an effective monitoring and reporting system (onco-pharmacovigilance) will be the most effective tool for better management of chemotherapy-related ADRs. Practices such as an early detection, timely intervention, avoiding agents with overlapping toxicity, or changing the offending agent and substituting it with an alternative agent are few suggestions. Onco-pharmacovigilance will increase the bulk of data on frequency, severity, outcome, etc., associated with anticancer drug use, particularly in the Indian population. We suppose that this will definitely help envisage strategy to prevent or deal with them more effectively. Medical, radio, and surgical oncologists, clinical pharmacologists, and other health-care providers involved in the care of cancer patients must all be involved in the onco-pharmacovigilance program to enhance the quality of data generated by exchanging and updating each other with constructive information. In addition, they should also ensure effective communication and education concerning the appropriate use of drugs in cancer patients.

The methods for ADR detection, evaluation, and monitoring should be strengthened from the grass-root level, especially in oncology. The role of pharmacovigilance program in monitoring the safety cancer chemotherapy should be evaluated for detection of newer and rarer ADRs. Improvement in spontaneous reporting of ADRs in oncology can only be achieved through sensitization and awareness lectures using audiovisual means not only to HCPs but also to residents, interns, and nurses as well. In addition, patient population should also be encouraged to report whenever they feel anything that in their opinion is not normal. Laboratory staff may also be vital in detecting any abnormality in laboratory tests consequent to drug exposure. Moreover, to strengthen ADR detection and reporting at grass-root level, the public at large may play an important role if they are well informed in their own language about proper use and safety of drugs through various means, i.e., TV, radio, print media, social media or public awareness lecture, etc. The motivation for voluntary reporting of ADRs for preventing the morbidity and mortality in this vulnerable population could be of immense importance.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We need to acknowledge and appreciate the efforts of the radiation oncology department. In spite of the shortage of health-care staff and availability of only one faculty member, the flow of ADR reporting never got stagnant. We also acknowledge the constant support and guidance provided by the National Coordinating Centre, IPC, Ghaziabad, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, from time to time.

References

- 1.Saini VK, Sewal RK, Ahmad Y, Medhi B. Prospective observational study of adverse drug reactions of anticancer drugs used in cancer treatment in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2015;77:687–93. doi: 10.4103/0250-474x.174990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma PK, Misra AK, Gupta N, Khera D, Gupta A, Khera P, et al. Pediatric pharmacovigilance in an institute of national importance: Journey has just begun. Indian J Pharmacol. 2017;49:390–5. doi: 10.4103/ijp.IJP_256_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad A, Parimalakrishnan S, Mohanta GP, Manna PK, Manavalan R. Incidence of adverse drug reactions with commonly prescribed drugs in tertiary care teaching hospital in India. Int J Pharm Sci. 2011;3:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart BW, Paul Kleihues P. World Cancer Report. Lyon, France: International Agency Research on Cancer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:117–28. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chabner BA. General principles of cancer chemotherapy. In: Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B, editors. Goodman and Gilman's the Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Inc; 2011. pp. 1667–75. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gandhi TK, Bartel SB, Shulman LN, Verrier D, Burdick E, Cleary A, et al. Medication safety in the ambulatory chemotherapy setting. Cancer. 2005;104:2477–83. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabbur RS, Emmerton L. An introduction to adverse drug reaction reporting system in different countries. Int J Pharm Prac. 2005;13:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turgay AS, Khorshid L, Eser I. Effect of the first chemotherapy course on the quality of life of cancer patients in Turkey. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31:E19–23. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000339248.37829.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma L, Wang SP, Chung J. A survey on correlative symptoms and its influence on quality of life in breast cancer patients. Chin J Evid Based Med. 2007;7:169–74. [Google Scholar]

- 11.ADR form PvPI. [Last accessed on 2017 Mar 06]. Available from: http://www.cdsco.nic.in/writereaddata/ADR%20form%20PvPI.pdf .

- 12.Skrbo A, Begović B, Skrbo S. Classification of drugs using the ATC system (Anatomic, therapeutic, chemical classification) and the latest changes. Med Arh. 2004;58:138–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaki SA. Adverse drug reaction and causality assessment scales. Lung India. 2011;28:152–3. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.80343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartwig SC, Siegel J, Schneider PJ. Preventability and severity assessment in reporting adverse drug reactions. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1992;49:2229–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schumock GT, Seeger JD, Kong SX. Control charts to monitor rates of adverse drug reactions. Hosp Pharm. 1995;30:1088, 1091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balmer CM, Valley AW, Iannucci A. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. 6th ed. USA: McGraw-Hill Companies; 2005. Cancer treatment and chemotherapy; p. 2279. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niraula S, Seruga B, Ocana A, Shao T, Goldstein R, Tannock IF, et al. The price we pay for progress: A meta-analysis of harms of newly approved anticancer drugs. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3012–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kshirsagar NA, Karande SC, Potkar CN. Adverse drug reaction monitoring in India. J Assoc Physicians India. 1993;41:374–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lumpkin MM. International pharmacovigilance: Developing cooperation to meet the challenges of the 21st century. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;86(Suppl 1):20–2. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2000.d01-6.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Misra AK, Thaware P, Sutradhar S, Rapelliwar A, Varma SK. Pharmacovigilance: Barriers and challenges. Mintage J Pharm Med Sci. 2013;2:35–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma PK, Singh S, Dhamija P. Awareness among tertiary care doctors about pharmacovigilance programme of India: Do endocrinologists differ from others? Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2016;20:343–7. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.180007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Surendiran A, Balamurugan N, Gunaseelan K, Akhtar S, Reddy KS, Adithan C, et al. Adverse drug reaction profile of cisplatin-based chemotherapy regimen in a tertiary care hospital in India: An evaluative study. Indian J Pharmacol. 2010;42:40–3. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.62412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soldin OP, Chung SH, Mattison DR. Sex differences in drug disposition. J Biomed Biotechnol 2011. 2011:187103. doi: 10.1155/2011/187103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Astolfi L, Ghiselli S, Guaran V, Chicca M, Simoni E, Olivetto E, et al. Correlation of adverse effects of cisplatin administration in patients affected by solid tumours: A retrospective evaluation. Oncol Rep. 2013;29:1285–92. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prasad A, Datta PP, Bhattacharya J, Pattanayak C, Chauhan AS, Panda P. Pattern of adverse drug reactions due to cancer chemotherapy in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Eastern India. J Pharmacovigil. 2013;1:107. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grunberg SM. Antiemetic activity of corticosteroids in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy: Dosing, efficacy, and tolerability analysis. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:233–40. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanlon JT, Ruby CM, Artz M. Geriatrics. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM, editors. Pharmacotherapy a Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Inc; 2002. pp. 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manohar HD, Adiga S, Thomas J, Sharma A. Adverse drug reaction profile of microtubule-damaging antineoplastic drugs: A focused pharmacovigilance study in India. Indian J Pharmacol. 2016;48:509–14. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.190725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma X, Yu H. Global burden of cancer. Yale J Biol Med. 2006;79:85–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mallik S, Palaian S, Ojha P, Mishra P. Pattern of adverse drug reactions due to cancer chemotherapy in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Nepal. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2007;20:214–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lau PM, Stewart K, Dooley M. The ten most common adverse drug reactions (ADRs) in oncology patients: Do they matter to you? Support Care Cancer. 2004;12:626–33. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wahlang JB, Laishram PD, Brahma DK, Sarkar C, Lahon J, Nongkynrih BS, et al. Adverse drug reactions due to cancer chemotherapy in a tertiary care teaching hospital. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2017;8:61–6. doi: 10.1177/2042098616672572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]