Abstract

Fresh harvested dates are perishable and there is a need for extending their shelf life while preserving their fresh like quality characteristics. This study evaluates three different freezing methods, namely cryogenic freezing (CF) using liquid nitrogen; individual quick freezing (IQF) and conventional slow freezing (CSF) in preserving the quality and stability of dates during frozen storage. Fresh dates were frozen utilizing the three methods. The produced frozen dates were frozen stored for nine months. The color values, textural parameters, and nutrition qualities were measured for fresh dates before freezing and for the frozen dates every three months during the frozen storage. The frozen dates’ color values were affected by the freezing method and the frozen storage period. There are substantial differences in the quality of the frozen fruits in favor of cryogenic freezing followed by individual quick freezing compared to the conventional slow freezing. The results revealed large disparity among the times of freezing of the three methods. The freezing time accounted to 10 min for CF, and around 80 min for IQF, and 1800 min for CSF method.

Keywords: Freezing methods, Frozen storage, Barhi dates, Quality preservation, Color values

1. Introduction

The date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) is a dominant tree in South West Asia and North Africa. Presently global production, consumption and industrial development of dates are constantly growing as date fruits are an important source of energy and essential nutrients and possess some medicinal benefits (Al Farsi and Lee, 2008, Al-Abdoulhadi et al., 2011, Chandrasekaran and Bahkali, 2013, Aleid et al., 2014).

The date fruits are categorized in three stages of maturity namely; Khalal, Rutab and Tamer depending on the color, texture, moisture and sugar content. The Khalal stage is the first edible stage at which the fruit reaches it maximum weight and size and its moisture content decreases so the total sugar and acidity will increase and the fruit is crispy and sweet with a bright yellow or red color. The Rutab stage follows the Khalal stage at this stage the fruit starts to ripe and the moisture content decreases to about 20% wet basis, sucrose turns to inverted sugars, the fruit skin turns to brown color, and softening of tissues takes place. The fruit is fully ripe at the Tamer with soft texture and the fruit contains its maximum total solids and it is in the best condition for storage (Farahnaky and Afshari-Jouybari, 2011).

There is a necessity to utilize freezing and frozen storage for prolonging the shelf life of fresh date fruits and preserving their quality characteristics, especially Barhi cultivar, which is favored and widely consumed at Khalal maturity stage. Frozen storage provides extra or substitute storage option that allows for the preservation of dates at their three stages of maturity (Khalal, Rutab and Tamer) compared to the dry storage of the Tamer stage (Al-Yahyai and Al-Kharusi, 2012).

Freezing and frozen storage can be utilized for the long term preservation of some fruits and vegetables. Freezing decreases water activity, inhibits microorganism growth and reduces enzymatic activity resulting in extending the shelf life of the product (Fellows, 2000, Heldman, 1992). Many published research works have confirmed the close relationship between quick freezing and high quality frozen products and the resulting increase shelf life with maximum preservation of initial quality (Sanz et al., 1999, Sun and Li, 2003, Zhang et al., 2004).

Color plays a fundamental part in the consumers’ evaluation of the food quality. Color changes are considered as the major quality attribute that affects consumers’ selection (Zhang et al., 2004). Enzymatic oxidation of phenolic substances is the main reason that induces color changing (browning). Ice crystals formed during freezing will enhance enzymatic oxidation due to the destruction the cells and tissues of the product and therefore increased contact between phenolics, oxygen and enzymes (Ruenroengklin et al., 2008). Textural parameters of frozen foods are essential in determining the acceptability of these products by consumers. Higher values of hardness, chewiness and resilience of the pulp indicate better quality products (Zhang et al., 2007, Krause et al., 2008, Kaushik et al., 2013). Several researchers have studied the effects of freezing on textural quality of fruits (Delgado and Rubiolo, 2005, Buggenhout et al., 2006, Sousa et al., 2007). Enzymatic activity is responsible for the quality deterioration in most of the frozen fruits. The enzyme activity decreases as the temperature decreases, however as a result of freezing, the chemical reactions catalyzed by the enzymes occur due to the increase in the concentration of salts (Maier et al., 1964, Whitaker, 1972, Marin and Cano, 1992). Fruit sugars have a significant part in preserving fruit quality and determining its nutritional status (Akhatou and Angeles, 2013). Dates, irrespective of the cultivars, contain more than 75% sugars on a dry-weight basis (Kanner et al., 1978). Al-Mashhadi et al. (1993) found that the reducing sugars (fructose and glucose) in date fruits increased while the sucrose sugar decreased at the end of twelve month of frozen storage. In another study a decrease in the reducing sugars of date fruits was reported at the end of six months of frozen storage (Mikki and Al-Taisan, 1993).

This research work deals with the study of the utilization and comparison of three freezing methods viz., cryogenic freezing using liquid nitrogen, individual quick freezing and conventional deep freezing on the quality and stability of date fruits (Barhi cultivar) at Khalal stage by evaluating color attributes, textural parameters, sugar contents, enzymatic activity and freezing rates during nine months of frozen storage. The outcome of this research is hoped to prove the feasibility of implementing modern freezing technologies to preserve fresh dates in a successful manner with a high level of quality preservation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Fresh dates

Fresh yellow dates (cv. Barhi) at Khalal stage of maturity were obtained from a commercial farm in Qassim, Saudi Arabia. Dates were sorted to discard the damaged fruits and immediately kept for less than 6 h in a cold store at 5 °C. Physical properties of the fresh date fruits (length and diameter; surface area; volume; mass; density), moisture content and water activity were measured. The color values, textural properties (hardness, elasticity, chewiness and resilience), and nutrition (enzymes, sugars) properties of the date fruits were evaluated for the fresh date fruits before freezing and for the frozen ones after thawing every three months during a period of nine month of frozen storage.

2.2. Moisture content and water activity determination

Moisture content was determined for the flesh of dates using the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) standard procedure (AOAC, 2005), where the samples were dried at 70 °C for 48 h under a vacuum of 200 mm of mercury (Vacutherm model VT 6025, Heraeus Instrument, D-63450. Hannover, Germany). Water activity of the dates flesh was measured at room temperature using Aqua-lab (Model CX-2T, readability 1 mg, Decagon Devices Inc., Washington).

2.3. Color examination

The fruit color values were expressed by the parameters (L∗, a∗, b∗) measured by a spectrophotometer device (Color Flex, Model No.45/0, Hunter Associates Laboratory. Inc., VA, USA), where L∗ indicates (whiteness or brightness/darkness), a∗ (redness/greenness) and b∗ (yellowness/blueness). In addition, the color was expressed by the total color difference (ΔE), chroma, hue angle and browning index (BI) as defined by the following equations (Maskan, 2001):

| (1) |

where L∗0, a∗0 and b∗0 are the color parameters of fresh fruits (before freezing) and L∗, a∗ and b∗ are the color parameters of fruits (after freezing).

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where

| (5) |

2.4. Texture profile analysis (TPA)

The texture profile analysis parameters were measured using a texture analyzer (TA-HDi, Model HD3128, Stable Micro Systems, Surrey, England). Fruit samples were compressed with a rod velocity of 1.5 mm/s to a depth of 5 mm. The compression was done twice to give two complete texture profile curves. The force–time deformation curves were obtained in which the following parameters were obtained: hardness (the maximum force required to compress the sample), resilience (the ability of the sample to recover its original form after deformation), and chewiness (the work needed to be done to make a solid food swallow-able, which is numerically formulated by the product of gumminess and springiness). Data were processed using Texture Expert Exceed, version 2.05 (Stable Micro Systems).

2.5. Extraction and estimation of invertase enzymes

The method described by Hasegawa and Smolensky (1970) was used to extract the invertase enzyme by mixing a sample (15 g) with NaCl solution (4%) containing 1 g polyvinyl polypyrrolidone for two min. at a temperature of 2 °C and then centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 30 min. at 5 °C. The upper liquid layer containing the enzyme (supernatant) was collected and kept for enzyme assay. The previous steps were repeated again on the remaining solid material and then the supernatant was taken and added to the previous amount. This solution is soluble invertase. The insoluble invertase was obtained by water dialysis of the extraction residues at 2 °C till all sugars were removed.

Invertase activity in Barhi dates at Khalal stage and during frozen storage was measured by a method based on Kanner et al. (1978). The assay mixture included 0.5 M acetate buffer pH 4.5, 1.5 M sucrose and enzyme extract (1 mL) with total volume of 5 mL. This mixture was kept for 1 h at 37 °C and I mL sample was withdrawn at 10 min interval. One unit of invertase was defined as the amount of enzyme, which hydrolyzed 0.5 μM sucrose per min under the above conditions.

2.6. Extraction and estimation of peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase enzymes

Peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase enzymes were extracted and estimated according to the method used by Cano et al. (1995). Each enzyme was extracted by 0.2 M sodium phosphate buffer and 1 M sodium chloride at 5 °C then filtered and centrifuged and the supernatant was collected. The amount of enzymes in the samples was measured using the polarization device (Polarimeter, Autopol IV Six Wavelength) manufactured by Rudolph Research, USA.

2.7. Sugar analysis

Sugar analysis (fructose, glucose, and sucrose) of dates was determined by the AOAC standard procedure (AOAC, 2005) using high-performance liquid chromatography system (HPLC), LC-10 AD, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan.

2.8. Freezing methods

Three different freezing methods were used in freezing the fresh date fruits namely, cryogenic freezing using liquid nitrogen, individual quick freezing using air blast and conventional slow freezing using traditional deep freezers.

2.8.1. Liquid nitrogen cryogenic freezing (CF) method

Continuous cryogenic freezer using liquid nitrogen (Cryogenic Freezing Tunnel, CQF 2076, Packo Inox NV, Torhout Sesteenweg, Zedelgem, Belgium) was utilized to freeze the fresh dates in a 4 m long tunnel. After the freezer reached steady state, fresh fruits were fed inside the tunnel at a rate of 5 kg/min. The frozen fruits were removed from the freezer after 12 min. from their entry. The temperature of the fruit pulp (near the pit) and the surrounding air inside the freezer tunnel were measured every 5 s using type K thermocouples connected with data Loggers. The freezer was set at −120 °C inside the tunnel. The frozen fruits were collected at the end of the freezing tunnel and packaged in rigid polyethylene boxes (1/2 kg capacity) and directly stored in ultra-freezers at −40 °C.

2.8.2. Individual quick freezing (IQF) method

Individual quick freezing using air as a medium to freeze (Advanced I.Q.F Spiral Freezer, Advanced Equipment Inc., Richmond, BC, Canada) was utilized to freeze the fresh dates. After the freezer reached steady state, fresh fruits were fed inside the freezer at a rate of 2 kg/min and the frozen fruits get out from the freezer after 34 min. The temperature of the fruit pulp (near the pit) and the surrounding air inside the freezer were measure every 5 s using type K thermocouples connected with data Loggers. The freezer was set at −43 °C inside the freezer. The frozen fruits were collected at the exit point of the freezer and packaged in rigid polyethylene boxes (1/2 kg capacity) and directly stored in ultra-freezers at −40 °C.

2.8.3. Conventional slow freezing using deep freezers (CSF) method

A traditional deep freezer (Chest Freezer, Sanyo Elec. Co., Ora/Gun Japan) was used for the conventional freezing of fresh fruits. The fruits were filled in rigid polyethylene plastic boxes (1/2 kg capacity). Thermocouples were placed to measure the temperature of the fruit pulp (near the pit) and the temperature inside the freezer every five minutes. Freezers’ temperature ranged between −18 and −24 °C at steady state. However, it was assumed that the average freezer temperature is −20 °C.

2.9. Thawing processes

The frozen fruits were removed from the storage freezers and thawed by leaving them at room temperature for two hours.

2.10. Statistical analysis

All needed statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS software package (IBM SPSS version 22), and data are represented as mean ± SD. Experimental data were analyzed by means of analysis of variance (ANOVA). The least significant difference (LSD) multi-comparison test was carried out to establish statistical differences between the calculated means and significant differences were reported at P ⩽ 0.05.at the 0.05 level.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Physical properties, moisture content and water activity

The data obtained on the physical properties of the fresh Barhi fruits are shown in Table 1. The average mass of the fruits of fresh Barhi fruits is 14.8 g. The average density values of the pulp of the fresh fruits, which is important for the calculation of temperature distribution within the fruit, were higher than the density of water as shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Mean values of the physical properties of fresh Barhi fruits at Khalal stage of maturity.

| Property | Mass (g) | Volume (cm3) | Density (g cm−3) | Area (cm2) | Length (mm) | Larger diameter (mm) | Diameter neck fruit (mm) | Diameter tip fruit (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 14.8 ± 2.6 | 14.5 ± 2.9 | 1.02 ± 0.05 | 27.9 ± 3.0 | 34.3 ± 2.0 | 27.5 ± 2.0 | 21.7 ± 1.3 | 19.2 ± 1.3 |

| No. of samples | 60 | 60 | 60 | 30 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

Table 2.

Mean values of pulp density, moisture content and pulp water activity for the fresh Barhi fruits at Khalal stage of maturity.

| Thickness of pulp (mm) | Density of pulp (cm3) | Moisture content (w.b.)% | Water activity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 8.1 ± 1.4 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 68.6 ± 5.2 | 0.911 ± 0.066 |

| No. of samples | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

Table 2 also shows the experimental data on the moisture content (wet basis) and water activity of the fresh Barhi fruits. The fresh Barhi fruits are characterized with high moisture content (68.6%) and water activity (0.91) values. This indicates that Barhi fruits were highly perishable.

3.2. Color of fresh and frozen fruits

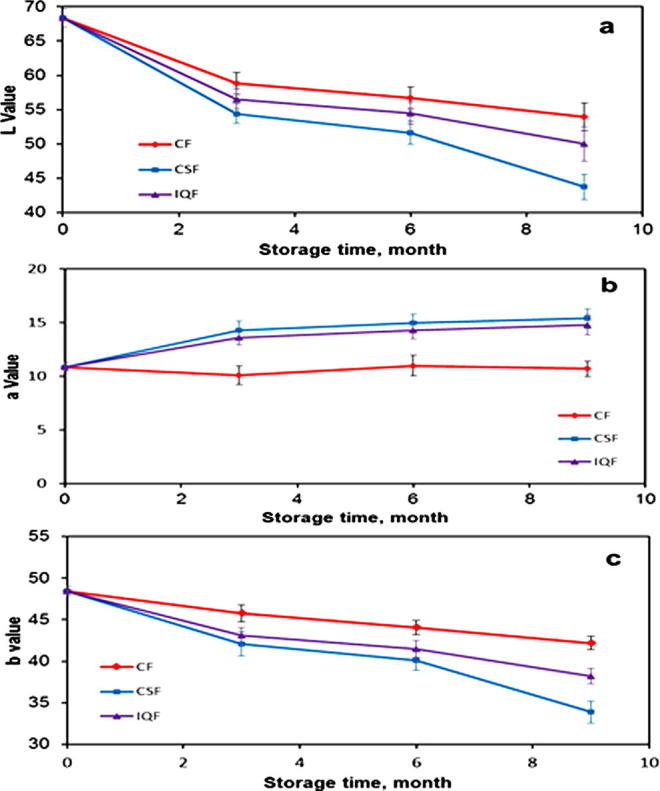

The experimental data on the basic color parameters (L∗, a∗ and b∗) of the Barhi fruits frozen by three freezing methods, i.e. CF, IQF and CSF as a function of time are displayed in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Changes of basic color parameter values of Barhi fruits frozen by CF, IQF and CSF at different storage times. (a) L∗, (b) a∗ and (c) b∗. (Mean value ± standard deviation of ten replicate measurements is shown.)

The mean values of the basic color parameters L∗, a∗ and b∗ of the fresh Barhi fruits were 68.35, 10.87 and 48.44, respectively. These values show that Barhi fresh fruits at Khalal stage of maturity are characterized with their bright yellow color. From Fig. 1 it is clear that the L∗, a∗ and b∗ values had changed for frozen fruits with the period of frozen storage which extended for nine months. The L∗ values of the frozen fruits decreased at the end of the frozen storage to 53.9, 50.0 and 43.7 in CF, IQF and CSF, respectively. While, a∗ values increased during the same period to 10.7, 14.8 and 15.4 in CF, IQF and CSF, respectively. The b∗ values followed the same behavior of L∗ and decreased to 42.2, 38.2 and 33.9 in CF, IQF and CSF, respectively.

Table 3 presents the comparison of the means color values of the frozen Barhi fruits as affected by the freezing method and storage time. As can be seen in Table 3, there were significant differences between the mean values of the basic color parameters (L∗, a∗ and b∗) of the fresh Barhi fruits and those of the fruits frozen by the three studied freezing methods and stored for different times of frozen storage at the level of P ⩽ 0.05.

Table 3.

Comparison of the mean color values of the frozen Barhi fruits as affected by the freezing method and storage time.

| Freezing method | Frozen storage time (month) | L∗ | a∗ | b∗ | ΔE | Hue angle | Chroma | BI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF | 0 | 68.35 a | 10.87 c | 48.44 a | 0.00 f | 77.32 ab | 49.64 a | 123.68 e |

| 3 | 58.8 b | 10.1 c | 45.8 ab | 9.94 e | 77.53 a | 46.90 ab | 143.36 d | |

| 6 | 56.7 bc | 11 c | 44.06 bc | 12.45 de | 75.95 ab | 45.41 bc | 144.51 d | |

| 9 | 53.9 cd | 10.7 c | 42.2 cde | 15.74 cd | 75.74 ab | 43.54 cd | 146.51 cd | |

| IQF | 0 | 68.35 a | 10.87 c | 48.44 a | 0.00 f | 77.32 ab | 49.64 a | 123.68 e |

| 3 | 54.4 c | 14.3 ab | 42.1 cde | 15.70 d | 71.21 cd | 44.46 c | 148.67 c | |

| 6 | 51.6 de | 15 a | 40.1 e | 19.16 bc | 69.46 de | 42.81 d | 151.56 b | |

| 9 | 43.7 f | 15.4 a | 33.9 g | 28.98 a | 65.54 f | 37.23 f | 155.47 a | |

| CSF | 0 | 68.35 a | 10.87 c | 48.44 a | 0.00 f | 77.32 ab | 49.64 a | 123.68 e |

| 3 | 56.5 bc | 13.6 b | 43.1 bcd | 13.28 de | 72.46 bc | 45.19 bc | 144.01 d | |

| 6 | 54.5 c | 14.3 ab | 41.5 de | 15.87 cd | 70.96 cd | 43.89 cd | 145.21 d | |

| 9 | 50 e | 14.8 a | 38.2 f | 21.38 b | 68.79 e | 40.97 e | 148.30 c |

∗The same letter in the same column (a, b, c etc.) indicates that the values are not significantly different at the 0.05 level.

These results indicate that there were notable changes in the values of the basic color parameters of the fresh Barhi fruits after freezing and frozen storage in the three freezing methods. Nevertheless, CF method is superior in preserving the fresh Barhi fruits’ basic color parameters compared to IQF and CSF method.

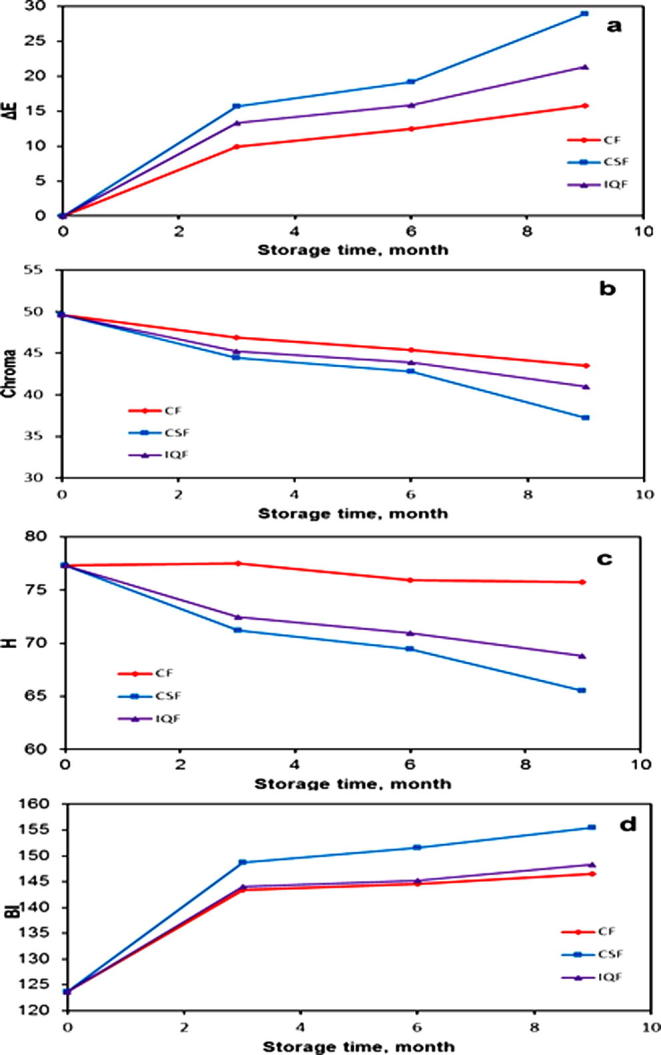

The data on the color derivative parameters i.e. color difference (ΔE), chroma, hue angle and browning index (BI) of the fruits frozen by CF, IQF and CSF methods are plotted and depicted in Fig. 2. The color derivative parameter values of the fruits frozen by CF, IQF and CSF methods varied depending on the period of the frozen storage. The color difference increased from zero for fresh fruits to 9.94, 13.28 and 15.7 after three months for CF, IQF and CSF, respectively and then reached a maximum value of 15.74, 21.38 and 28.98 after 9 months of frozen storage for CF, IQF and CSF, respectively. Chroma values decreased from 49.64 for fresh fruits to 46.90, 45.19 and 44.46 after three months for CF, IQF and CSF, respectively. Chroma reached values of 43.54, 40.97 and 37.23 after nine months of frozen storage for CF, IQF and CSF, respectively. The hue angle values for fresh Barhi fruits decreased from 77.32 to 75.74, 68.79 and 65.54 for CF, IQF and CSF, respectively, while the browning index values increased from 123.68 to 146.5, 148.3 and 155.47 for the frozen fruits stored of a period of nine months for CF, IQF and CSF, respectively. The results of the CSF method indicate a large decrease in the values of L∗ and b∗ after nine months of frozen storage. This has led to a significant decrease in chroma and the hue angle values and an increase in the color difference and browning index compared to the CF and IQF.

Figure 2.

Changes of color derivative parameters values of Barhi fruits frozen by CF, IQF and CSF at different storage times. (a) Color deference (ΔE), (b) chroma, (c) hue angle and (d) BI.

Table 3 also displays that there were significant differences at the level of P ⩽ 0.05 between the color derivative parameters (ΔE, chroma, and BI) of the fresh Barhi fruits and those of the fruits frozen by the three studied freezing methods and stored for different times of frozen storage. However, there were no significant differences in the hue angle values of the frozen fruits by CF method and stored for the different times of frozen storage, while there were significant differences at the level of P ⩽ 0.05 between the three freezing methods.

The differences in the changes of the frozen fruits’ color observed in the freezing methods studied may be due to the differences in enzymatic oxidation of phenolic substances. The different sizes of ice crystals formed via different freezing methods will enhance different enzymatic oxidation of phenolic substances (Ruenroengklin et al., 2008). The above results were similar to those observed by several researchers (Duan et al., 2007, Neog and Saikia, 2010, Ruenroengklin et al., 2008).

3.3. Textural parameters

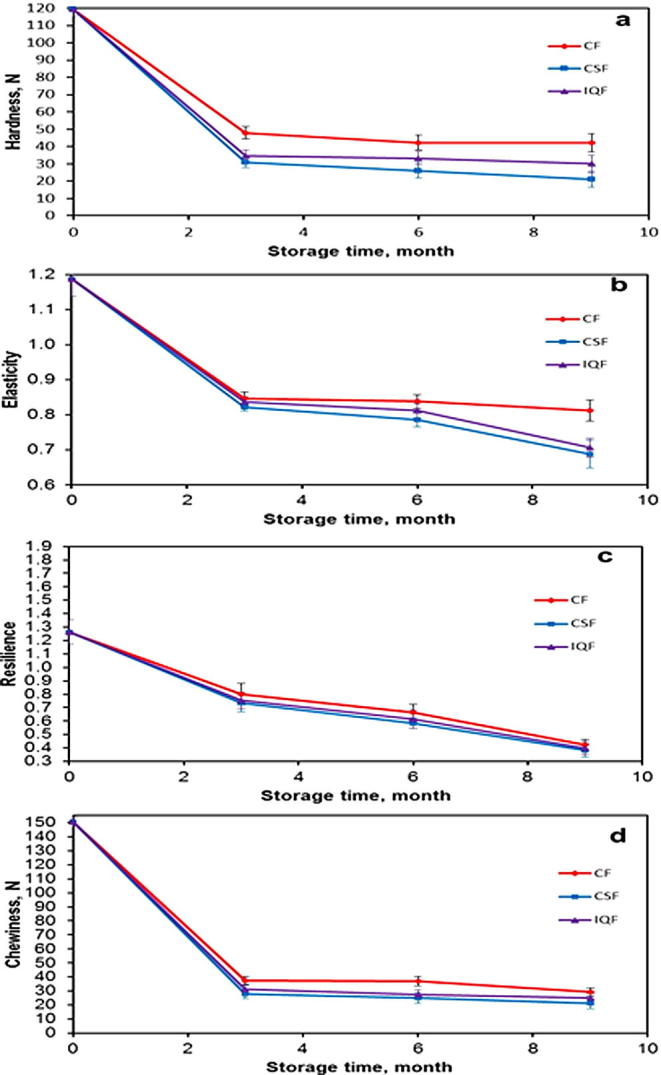

The textural profile analysis (TPA) parameters for the fresh fruits and frozen fruits (after thawing) during nine months of frozen storage are shown in Fig. 3. The results indicate that fresh Barhi fruits are distinguished with their higher mechanical properties. The results also depict that fresh Barhi fruit is firm as revealed by its high average hardness value (119.48 N).

Figure 3.

Effects of freezing methods on the TPA parameters of Barhi fruits at different storage times. (a) Hardness, (b) elasticity, (c) resilience and (d) chewiness. (Mean value ± standard deviation of ten replicate measurements is shown.)

The TPA parameters of the frozen fruits were highly influenced by freezing method and frozen storage time. In general, all tested TPA parameter values of the fruits frozen were lower compared to the fresh ones. This is apparent in the high changes of texture after storage of three months. However, it tends to be more stable after six and nine months of storage.

As displayed in Fig. 3(a) the reduction in hardness values of the fruits during the first three months of storage is 59.8%, 71% and 74.17% for CF, IQF and CSF, respectively. It is also noted that the hardness of the fruits frozen via CF and IQF methods decrease by 12.1% and 13.17%, respectively, during the storage period of three to nine months. On the other hand, the decline of hardness of the fruits frozen via CSF during the same period was much larger (32%).

The reduction in the elasticity values for the fruits frozen by CF, IQF and CSF methods is illustrated in Fig. 3(b). It is clear that the decline is at a higher rate in CSF compared to CF and IQF methods. The resilience property of the frozen fruits decreased during frozen storage for the three freezing methods.

Fig. 3(c) displays that the resilience of fresh fruits decreased by 36.8%, 40.27% and 41.69% for CF, IQF and CSF methods, respectively during the three first months of storage. The chewiness values of fresh fruits decreased during the same period of storage by 75.2%, 79.27% and 81.39% for CF, IQF and CSF methods, respectively as given in Fig. 3(d). In addition, the elasticity of fresh fruits decreased during the three first months of storage by 28.78%, 29.55% and 32% for CF, IQF and CSF methods, respectively as shown in Fig. 3(b).

Table 4 presents the comparison between the mean values of the TPA parameters for the fresh and frozen Barhi fruits as affected by the freezing method and storage time. From the table it can be seen that there were significant differences between the values of the hardness of the fresh and frozen Barhi fruits for the three studied freezing methods. There were no significant differences between the hardness values of the frozen fruits stored for different times of frozen storage using CF and IQF freezing methods. Nevertheless, for the fruits frozen by CSF method there were significant differences between their hardness values at the level of P ⩽ 0.05.

Table 4.

Comparison of the means TPA parameters values of the frozen Barhi fruits as affected by the freezing method and storage time.

| Freezing method | Frozen storage time (month) | Hardness | Elasticity | Resilience | Chewiness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF | 0 | 119.476 a | 1.188 a | 1.264 a | 150.760 a |

| 3 | 47.995 b | 0.846 a | 0.798 b | 37.380 b | |

| 6 | 42.226 b | 0.838 a | 0.664 d | 36.858 b | |

| 9 | 42.204 b | 0.813 a | 0.424 g | 29.351 cd | |

| IQF | 0 | 119.476 a | 1.188 a | 1.264 a | 150.760 a |

| 3 | 34.555 c | 0.837 a | 0.755 c | 31.262 c | |

| 6 | 33.257 c | 0.812 a | 0.613 e | 27.425 de | |

| 9 | 30.004 cd | 0.706 a | 0.400 h | 25.011 e | |

| CSF | 0 | 119.476 a | 1.188 a | 1.264 a | 150.760 a |

| 3 | 30.859 c | 0.821 a | 0.737 c | 28.056 d | |

| 6 | 26.021 d | 0.786 a | 0.582 f | 24.834 e | |

| 9 | 21.040 e | 0.688 a | 0.382 i | 21.020 f |

∗The same letter in the same column (a, b, c etc.) indicates that the values are not significantly different at the 0.05 level.

From Table 4 it can be realized that there were no significant differences between the elasticity values of the frozen fruits stored for different times of frozen storage using the three studied freezing methods at the level of P ⩽ 0.05. However, there were significant differences between the resilience and chewiness values of the frozen fruits stored for different times of frozen storage using the three studied freezing methods at the level of P ⩽ 0.05.

The above mentioned results showed that CF method is preferable compared to IQF and CSF methods since deterioration in texture changes is less for the first method and closer to natural texture of Barhi fresh fruits. This is probably due to decrease of the injurious effects of crystallization and recrystallization on the microstructure of Barhi tissues during such quick freezing, frozen storage and thawing using CF method. These results proved the reported significant role of the freezing rate in maintaining the texture of frozen foods (Buggenhout et al., 2006, Delgado and Rubiolo, 2005, Sanz et al., 1999, Sousa et al., 2007, Sun and Li, 2003, Zhang et al., 2004).

3.4. Effects of freezing methods on the enzymatic activity of Barhi fruits

Invertase enzyme activity was not detected in Barhi fruits (Khalal stage). This may be due to the temperature at which the dialysis process of the extract was done. Another possibility is that the invertase enzyme exists at minute quantities in the cultivar under study to the extent that it was out of the detection limits.

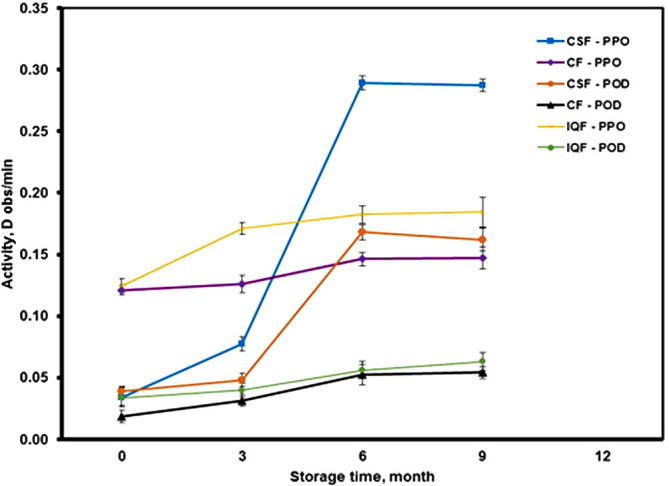

The enzymatic activity of both polyphenol oxidase (PPO) and peroxidase (POD) in Barhi fruits throughout frozen storage period (9 months) is shown in Fig. 4. It is evident from this figure there is an increase in the activity of both enzymes in the three freezing methods, but the increase in CSF is greater. This may be due to the enzymatic activity in the fruits as a result of no use of blanching treatment. Moreover, it is noted that the activity of both enzymes increased at a slower rate in the first three months. Then the activity increased dramatically during the next three months, while it was almost constant during the last three months. As for CF and IQF methods the activity of the two enzymes increased, but at very small rates during the frozen storage for a period of nine months. These enzyme activities might be the cause for the deterioration of fruit texture and color during storage (Whitaker, 1972, Marin and Cano, 1992). Moreover, the enzyme activities are more active when freezing with CSF compared to CF and IQF which might indicate the slower activities of CF and IQF that led to retention of fruit properties more than that of CSF.

Figure 4.

Effects of freezing methods on the enzymes activity of Barhi fruits at different storage times. (Mean value ± standard deviation of ten replicate measurements is shown.)

Table 5 presents the comparison between the means values of the enzymatic activity and sugars of the frozen Barhi fruits as affected by the freezing method and storage time. It can be perceived from the table that there were no significant differences between the PPO and POD values for the different freezing methods and frozen storage times at the level of P ⩽ 0. 05.

Table 5.

Comparison of the mean values of the enzymatic activity and sugars of the frozen Barhi fruits as affected by the freezing method and storage time.

| Freezing method | Frozen storage time (month) | PPO | POD | Sucrose | Glucose | Fructose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF | 0 | 0.034 b | 0.039 bc | 21.820 a | 5.040 b | 4.640 b |

| 3 | 0.077 b | 0.048 bc | 4.080 cd | 25.350 a | 22.930 a | |

| 6 | 0.289 a | 0.168 a | 3.110 d | 14.510 b | 8.250 b | |

| 9 | 0.287 a | 0.162 a | 0.000 d | 12.950 b | 7.590 b | |

| IQF | 0 | 0.125 b | 0.034 bc | 19.070 a | 8.070 b | 6.810 b |

| 3 | 0.171 b | 0.040 bc | 16.500 a | 8.070 b | 6.950 b | |

| 6 | 0.182 b | 0.056 b | 10.890 bc | 12.280 b | 10.250 b | |

| 9 | 0.184 b | 0.063 b | 5.140 cd | 10.740 b | 7.680 b | |

| CSF | 0 | 0.121 b | 0.018 c | 19.200 a | 7.400 b | 6.560 b |

| 3 | 0.126 b | 0.031 bc | 17.800 a | 7.800 b | 6.820 b | |

| 6 | 0.146 b | 0.052 b | 13.770 ab | 11.380 b | 9.040 b | |

| 9 | 0.147 b | 0.054 b | 12.320 ab | 7.930 b | 7.260 b |

∗The same letter in the same column (a, b, c etc.) indicates that the values are not significantly different at the 0.05 level.

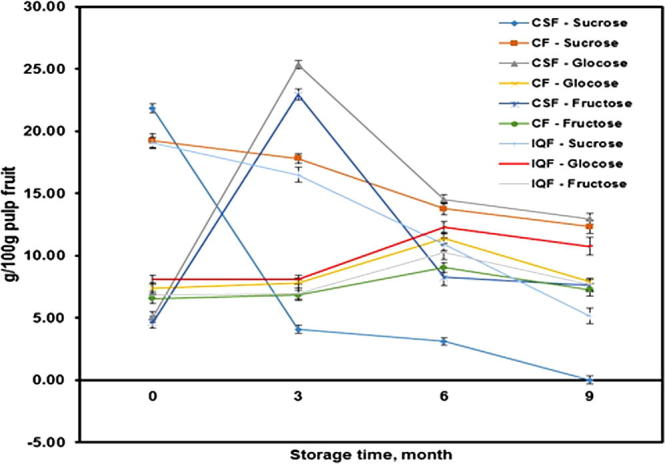

3.5. Effects of freezing methods on Barhi fruits’ sugars

Fig. 5 displays the effects of CF, IQF and CSF methods and frozen storage period on the fresh Barhi fruit sugars. For the fruits frozen by CSF method and stored at −20 °C, the proportion of glucose and fructose has increased substantially during the first three months of frozen storage. This proportion decreased considerably during the following three months and continued to decrease at a lower rate until the end of the frozen storage period. Whereas, sucrose proportion greatly declined by about 81% of its initial value at the end of the first three months. The sucrose has gradually faded or disappeared completely until the end of the storage period. The disappearance of or decomposition of sucrose is probably due to enzymatic activity in the fruit.

Figure 5.

Effects of freezing methods on Barhi fruits’ at different storage times. (Mean value ± standard deviation of ten replicate measurements is shown.)

For the fruits frozen by CF and IQF methods and stored at −40 °C, the glucose and fructose percentages increased at slow and regular rate until the end of the sixth month of storage then decreased gradually until the end of the ninth month. The sucrose percentage decreased gradually till the end of the frozen storage period. This increase in the reducing sugars (fructose and glucose) perceived during the first period of frozen storage for both studied freezing methods was also observed by Al-Mashhadi et al. (1993) for date fruits. The reduction in the reducing sugars that was detected during the last period of storage was stated by Mikki and Al-Taisan (1993).

Table 5 displays that there were significant differences between the sucrose values of the fruits frozen by IQF and CSF methods for the different frozen storage times at the level of P ⩽ 0.05. But then there were no significant differences between the sucrose values of the fruits frozen by CF method. There were no significant differences between the fructose and glucose values of the fruits frozen by the three freezing methods for the different frozen storage times at the level of P ⩽ 0.05.

From the above results it is evident that the changes in sugars were much lower in case of fruits frozen by CF method and stored at −40 °C compared to those frozen by IQF and CSF methods.

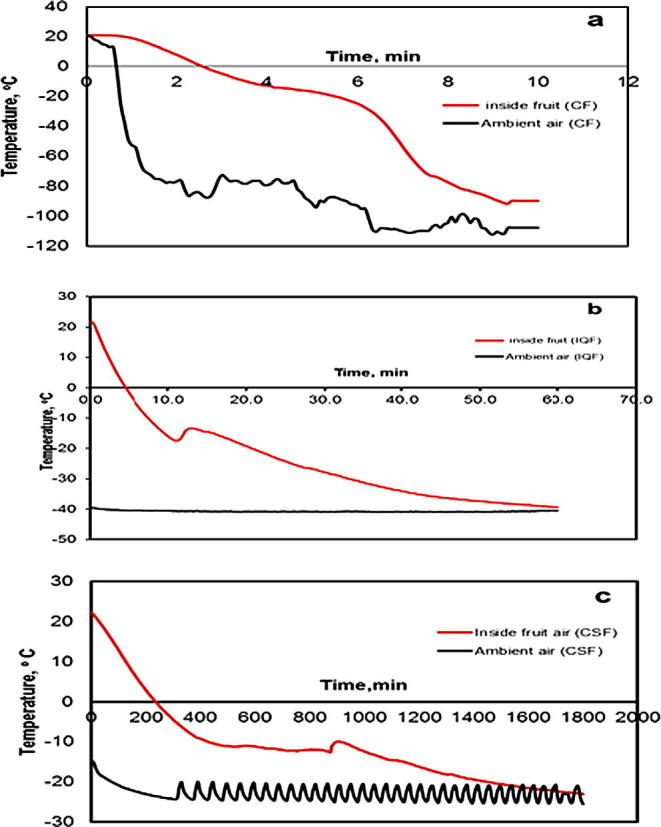

3.6. Fruits’ freezing curves

Freezing curves of fresh Barhi fruits during CF are shown in Fig. 6(a). The curves represent the change of the fruit center and its surrounding air temperature with time. From the figure it is seen that the temperatures dropped during the first five minutes from initial temperature of 21 °C to −22.1 °C and −91.8 °C at the fruit center and its surroundings air, respectively. From the freezing curves, it is shown that the temperature of the fruit center dropped to −26.4 °C after six minutes in the freezer and about two minutes later it fell to −74.7 °C. At the end of ten minutes from the beginning of the freezing process the temperatures dropped to −95 °C and −107.8 °C at fruit center and its surroundings air, respectively.

Figure 6.

Temperature change with time during CF, IQF and SCF of Barhi fruits.

Freezing curves of fresh Barhi fruits during IQF are presented in Fig. 6(b). The curves represent the change of the fruit center and its surrounding air temperature with time. From the figure it is perceived that the temperatures dropped during the first five minutes from initial temperature of 21 °C to −2 °C and −40.4 °C at the fruit center and its surrounding air, respectively. From the freezing curves, it is revealed that the temperature of the fruit center fell to −15.9 °C after ten minutes in the freezer. At the end of one hour from the beginning of the freezing process the temperatures fell to −39.3 °C and −40.5 °C at fruit center and its surroundings air, respectively.

The results of CSF for fresh Barhi fruits are illustrated in Fig. 6(c). The freezing curves in this figure show a decrease in the temperature of the fruit center from 21.6 °C to zero degree after 4:41 h. The temperature of the fruit center dropped to −9.5 °C after 10 h then to −18.1 °C after 24 h to reach −21.2 °C after 30 h of freezing. The air temperature inside the closed pack containing the fruits approach the temperature of the fruit surface, while the temperature inside the freezer was fluctuating after reaching steady state where it varied in the range of −20.9 °C to −24.3 °C.

It can be noted that CF method is superior of fruit quality preservation followed by IQF method and that may be due to the shorter freezing time. The freezing time taken to reach the fruit center accounted to 10 min for CF, and around 80 min for IQF, and 1800 min for CSF method.

3.7. Economic aspects

The financial study for the project # (AR 20-48) indicated that the total cost needed to freeze one kilogram of fresh dates accounted to 1.43, 0.91, 0.80 USD using IQF, and around 1.70, 1.20, and 1.10 USD using CF, for annual production rates of 1000, 3000, and 5000 tons of frozen dates, respectively. The economic study concluded that the highest annual production rate (5000 tons) using the IQF system is the best economic alternative, taking into account that date fruits frozen using CF method were of higher quality compared to those frozen via IQF method as shown by the above results (Alhamdan et al., 2007).

4. Conclusions

Freezing and frozen storage of fresh Barhi fruits exhibited clear effects on basic color values (L∗, a∗ and b∗) and their derivative parameters. Freezing and freezing methods greatly influenced the textural properties of the fruits. In general, textural parameters decreased with storage time and were dependent on freezing method. Analysis of basic sugars (fructose, glucose, and sucrose) in the fruits showed a sharp increase in fructose and glucose and a decrease in sucrose for fruits until the end of the frozen storage period. The increase of enzymatic activities of poly phenol oxidase and peroxidase led to a more deterioration of fruit quality with storage time especially with conventional slow freezing method. Temperature distribution curves showed a high variation of freezing times of the three examined systems. There was a large difference between the times of freezing of the three methods in favor of cryogenic freezing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank King Abdulazizi City for Science and Technology for financially supporting project # AR 20-48. Thanks extended to the Vice Deanship of Research Chairs, King Saud University.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Akhatou I., Angeles F.R. Influence of cultivar and culture system on nutritional and organoleptic quality of strawberry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013;94(5):866–875. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Farsi M.A., Lee C.Y. Nutritional and functional properties of dates: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008;48:877–887. doi: 10.1080/10408390701724264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Abdoulhadi I.A., Al-Ali S., Khurshid K., Al-Shryda F., Al-Jab A.M., Ben A.A. Assessing fruit characteristics to standardize quality norms in date cultivars of Saudi Arabia. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2011;4(10):1262–1266. [Google Scholar]

- Aleid S.M., Elansari A.M., Tang Z.X., Almaiman S.A. Effect of frozen storage and packing type on khalas and sukkary dates quality. Am. J. Food Technol. 2014;9:127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Alhamdan, A.M., Hassan, B.H., Al-Kahtani, H., Ismaiel, S.M., 2007. Economic aspects. In: Production of High Quality Frozen Rutab from Selected Saudi Date Cultivars. Final Technical Project # AR 20-48, General Directorate of Research Grants Programs, King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, pp. 287–292 (In Arabic).

- Al-Mashhadi, A.S., Al-Shalhat, A.F., Faoual, A., Abo-Hamrah, A.A., 1993. Storage and preservation of dates at Rutab stage. In: Proceedings of the Third Symposium on the Date Palm in Saudi Arabia, King Faisal University, Al-Hassa, Saudi Arabia, January 17–20, pp. 253–266 (In Arabic).

- Al-Yahyai R., Al-Kharusi L. Physical and chemical quality attributes of freeze-stored dates. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2012;14(1):97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists – International [AOAC] 18th ed. AOAC; Gaithersburg, MD, USA: 2005. Official Methods of Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Buggenhout S.V., Messagie I., Maes V., Duvetter T., Van Loey A., Hendrickx M. Minimizing texture loss of frozen strawberries: effect of infusion with pectin methyl esterase and calcium combined with different freezing conditions and effect of subsequent storage/thawing conditions. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006;223(3):395–404. [Google Scholar]

- Cano M.P., Ancos B.D., Lobo G. Peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase activities in papaya during post-harvest ripening and after freezing/thawing. J. Food Sci. 1995;60(4):815–817. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran M., Bahkali A.H. Valorization of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) fruit processing by-products and wastes using bioprocess technology – review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2013;20(2):105–120. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado A.E., Rubiolo A.C. Microstructural changes in strawberry after freezing and thawing processes. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 2005;38(2):135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Duan X., Wu G., Jiang Y. Evaluation of the antioxidant properties of litchi fruit phenolics in relation to pericarp browning prevention. Molecules. 2007;12(4):759–771. doi: 10.3390/12040759. http://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/12/4/759/molecules-12-00759.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farahnaky A., Afshari-Jouybari H. Physiochemical changes in Mazafati date fruits incubated in hot acetic acid for accelerated ripening to prevent diseases and decay. Sci. Hortic. 2011;127:313–317. [Google Scholar]

- Fellows P.J. second ed. Wood head Publishing; Cambridge, UK: 2000. Food Processing Technology: Principles and Practice; p. 610. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa S., Smolensky D.C. Date invertase: properties and activity associated with maturation and quality. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1970;18(5):902–904. [Google Scholar]

- Heldman D.R. Food freezing. In: Heldman D.R., Lund D.B., editors. Handbook of Food Engineering. Marcel Dekker Inc.; New York: 1992. pp. 277–315. [Google Scholar]

- Kanner J., Elamaleh H., Reuveni O., Ben-Gera I. Invertase (β-Fructofuranosidase) activity in three date cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1978;26(5):1238–1240. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik N., Kaur B.P., Rao P.S. Application of high pressure processing for shelf life extension of litchi fruits (Litchi chinensis cv. Bombai) during refrigerated storage. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2013;1:1–15. doi: 10.1177/1082013213496093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause A.J., Miracle R.E., Sanders T.H., Dean L.L., Drake M.A. The effect of refrigerated and frozen storage on butter flavor and texture. J. Dairy Sci. 2008;91(2):455–465. doi: 10.3168/jds.2007-0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier V.P., Metzler D.M., Huber A.F. 3-O-Caffeoylshikimic acid (dactylifric acid) and its isomers, a new class of enzymic browning substrates. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1964;14:124–128. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(64)90241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin M.A., Cano M.A. Patterns of peroxidase in ripening mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruits. J. Food Sci. 1992;57:690–692. [Google Scholar]

- Maskan M. Kinetics of color change of kiwifruits during hot air and microwave drying. J. Food Eng. 2001;48:169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Mikki, M.S., Altaisan, S.M., 1993. Physicochemical changes associated with freezing storage of date cultivars at their Rutab stage of maturity. In: Proceedings of the Third Symposium on the Date Palm in Saudi Arabia, King Faisal University, Al-Hassa, Saudi Arabia, January 17–20, pp. 253–266 (In Arabic).

- Neog M., Saikia L. Control of post-harvest pericarp browning of litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn) J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010;47(1):100–104. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0001-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruenroengklin N., Zhong J., Duan X., Yang B., Li J., Jiang Y. Effects of various temperatures and pH values on the extraction yield of phenolics from Litchi fruit pericarp tissue and the antioxidant activity of the extracted anthocyanins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2008;9:1333–1341. doi: 10.3390/ijms9071333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz P.D., De Elvira C., Martino M., Zaritzky N., Otero L., Carrasco J.A. Freezing rate simulation as an aid to reducing crystallization damage in foods. Meat Sci. 1999;52(3):275–278. doi: 10.1016/s0309-1740(99)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa M.B., Canet W., Alvarez M.D., Fernandez C. Effect of processing on the texture and sensory attributes of raspberry (cv. Heritage) and blackberry (cv. Thornfree) J. Food Eng. 2007;78(1):9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sun D., Li B. Microstructural change of potato tissues frozen by ultrasound-assisted immersion freezing. J. Food Eng. 2003;57(4):337–345. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker J.R. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1972. Principles of Enzymology for the Food Science; p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Duan Z., Zhang J., Peng J. Effects of freezing conditions on quality of areca fruits. J. Food Eng. 2004;61(3):393–397. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Zhang H., Wang L., Gao H., Guo X.N., Yao H.Y. Improvement of texture properties and flavor of frozen dough by carrot (Daucus carota) antifreeze protein supplementation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55(23):9620–9626. doi: 10.1021/jf0717034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]