Abstract

Purpose: High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) contributes to adverse disease outcome in Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. This study tests Box A, an HMGB1 antagonist, in a model of the disease.

Methods: C57BL/6 mice (B6) were injected subconjunctivally (1 day before infection) with Box A or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), infected with P. aeruginosa strain ATCC 19660, and injected intraperitoneally with Box A or PBS at 1 and 3 days postinfection (p.i.). Clinical scores, photographs with a slit lamp camera, real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), western blot, immunohistochemistry, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), myeloperoxidase (MPO), and bacterial plate count were used to assess disease outcome. In separate experiments, the therapeutic potential of Box A was tested as described above, but with treatment begun at 6 h p.i.

Results: Box A versus PBS prophylactic treatment significantly reduced clinical scores, MPO activity, bacterial load, and expression of TLR4, RAGE, IL-1β, CXCL2, and TNF-α in the infected cornea. Box A blocked co-localization of HMGB1/TLR4 in infiltrated cells in the stroma at 3 and 5 days p.i., but only at 5 days p.i. for HMGB1/RAGE. Box A versus PBS therapeutic treatment significantly reduced clinical scores, MPO activity, bacterial load, and protein levels of IL-1β, CXCL2, and IL-6 in the infected cornea.

Conclusion: Overall, Box A lessens the severity of Pseudomonas keratitis in mice by decreasing expression of TLR4, RAGE (their interaction with HMGB1), IL-1β, CXCL2 (decreasing neutrophil infiltrate), and bacterial plate count when given prophylactically. Therapeutic treatment was not as effective at reducing opacity (disease), but shared similar features with pretreatment of the mice.

Keywords: Box A, cornea, TLR4, RAGE, mice

Introduction

High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) is a 215 amino acid nuclear protein, with a highly conserved amino acid identity (99%) between humans and rodents.1,2 During injury, infection or sterile inflammation HMGB1 is released to the extracellular surface by damaged or activated immune cells.1,2 Extracellularly, HMGB1 functions as a nonclassical proinflammatory cytokine and has been defined as a late mediator of the inflammatory response, possessing a wide therapeutic window.3–5 This delayed kinetics of extracellular release (18 to 72 h after insult) and the positive correlation between the elevated levels of HMGB1 and the pathogenesis of disease6 (e.g., in keratitis7 and sepsis3) led to identification of HMGB1 as a novel therapeutic target. HMGB1 is composed of 3 functional domains; the proinflammatory (Box B), HMGB1 antagonist (Box A), and C-terminal acidic tail (C tail).8–10 Structure-function analysis has shown that the active cytokine domain of HMGB1 is localized to the DNA-binding Box B, whereas the Box A competes with HMGB1 for binding sites on the surface of cells (e.g., activated macrophages) and attenuates the biologic function of the full-length HMGB1; thus Box A acts as a specific antagonist of HMGB1.9–12

Box A plays an important role in attenuation of the inflammatory response in sepsis induced by lethal peritonitis, arthritis, and LPS-induced acute lung injury and pancreatitis.9–12 Box A binds to receptors for HMGB1 such as RAGE, TLR2, and TLR4 without any intrinsic proinflammatory activity.9 In contrast, antibody against HMGB1 neutralizes the activity of the molecule, but does not completely block these multi-ligand signal transduction receptors. This ultimately leads to activation of NF-κB and its nuclear translocation, resulting in secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and to suppression of chemoattractant cytokines. Box A not only antagonizes HMGB1 binding, but also attenuates HMGB1-induced release of proinflammatory cytokines,9 both of which suggest strong therapeutic potential. Studies also demonstrate that even delayed treatment with Box A is capable of specific inhibition of endogenous HMGB1 and therapeutically reversed lethality of established sepsis.9 However, despite these provocative data, nothing is known regarding the role of Box A and its antagonistic effects on HMGB1 as a treatment for experimental microbial keratitis.

Methods

Human corneal samples

Human corneal samples were obtained from patients presenting with bacterial keratitis to the Department of Ophthalmology (The Affiliated Hospital of Qindao University) from January 2012 to December 2016. The patients enrolled in the study had their bacterial keratitis clinically confirmed by staining of corneal scrapings, bacterial culture to verify Pseudomonas aeruginosa growth, or confocal microscopy. In total, 6 healthy corneal tissue samples were harvested after enucleation of the eye and 6 corneal samples from patients with P. aeruginosa infection were harvested after corneal transplantation and were used for immunofluorescence analysis. All subjects gave informed consent before participation in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qindao University.

Animals and infection model

Eight-week-old female C57BL/6 (B6) mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were housed per the National Institutes of Health guidelines. Animals were treated humanely, in compliance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

P. aeruginosa strain 19660 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was grown in peptone tryptic soy broth medium in a rotary shaker water bath at 37°C, 150 rpm for 18 h to an optical density (measured at 540 nm) between 1.3 and 1.8. Bacterial cultures were pelleted by centrifugation at 5,500 g for 10 min. Pellets were washed with sterile saline, resuspended, and diluted in sterile saline to 1 × 106 CFU/μL.13 Mice, anesthetized using ethyl ether, were viewed with a stereoscopic microscope ( × 40 magnification) and the left cornea scratched (three 1-mm wounds) with a sterile 255/8 gauge needle. To initiate infection, a 5 μL aliquot of the bacterial suspension was pipetted onto the cornea.

Response to infection

Clinical scores were used as described before14 to statistically compare disease severity that was scored as follows: 0 = clear or slight opacity, partially or fully covering the pupil; +1 = slight opacity, fully covering the anterior segment; +2 = dense opacity, partially or fully covering the pupil; +3 = dense opacity, covering the entire anterior segment; and +4 = corneal perforation or phthisis. Photographs were taken with a slit lamp camera at 5 days postinfection (p.i.) to illustrate disease.

Treatment with Box A

For prophylactic treatment, the left eye of B6 mice (n = 5/group/time) was injected subconjunctivally the day before infection with 1 μg/5 μL Box A (Tecan US, Inc., Morrisville, NC) or 5 μL PBS. On days 1 and 3 p.i. mice received 10 μg/100 μL Box A or PBS intraperitoneally (i.p.). This procedure is used as the subconjunctival injection the day before infection, will assure that the Box A is immediately adjacent to its target the cornea for absorption. The i.p. injections are used afterward, when the infection has caused the cornea to swell and allows penetration of the injected Box A. It is a procedure we have used in all past similar studies.7,13 In a separate experiment, to test the therapeutic efficacy of Box A treatment, 1 μg/5 μL Box A or PBS was injected subconjunctivally 6 h p.i. with i.p. injections performed as described above at 1 and 3 days p.i.

Neutrophil (polymorphonuclear neutrophil [PMN]) infiltrate

To quantitate polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) in the infected cornea of Box A versus PBS-treated mice, a myeloperoxidase (MPO) assay was used.15 For this, corneas were removed at 3 and 5 days p.i. and individually homogenized in 1.0 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 0.5% hexadecyltrimethyl-ammonium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). After 4 freeze-thaw cycles, samples were centrifuged and 100 μL of the supernatant was added to 2.9 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer containing o-dianisidine dihydrochloride (16.7 mg/mL; Sigma) and hydrogen peroxide (0.0005%). Absorbance changes were monitored at 460 nm for 5 min (30 s intervals). Units of MPO/cornea were calculated; one unit = ∼2 × 105 PMN.15

Plate count

Mice were sacrificed on 3 and 5 days p.i., and infected corneas of Box A and PBS-treated mice (prophylactic and therapeutic) (n = 5/group/time/experiment) were collected. Each cornea was homogenized in 1 mL sterile saline with 0.25% bovine serum albumin (BSA); 100 μL was serially diluted 1:10 (sterile saline with 0.25% BSA). Selected dilutions were plated in triplicate on Pseudomonas isolation agar plates (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), incubated overnight at 37°C, colonies counted, and results expressed as log10 CFU/cornea ± SEM.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Box A and PBS-treated mice were sacrificed (5 days p.i.) and normal and infected corneas collected. Total RNA was isolated (RNA STAT-60; Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX) from each cornea per the manufacturer's instructions. After spectrophotometric quantification (260 nm), 1 μg of each sample was reverse transcribed using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), yielding a cDNA template. cDNA products were diluted (1:25) with diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water. A 2 μL aliquot was used for real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) with Real-Time SYBR Green/Fluorescein PCR Master Mix (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) and primer concentrations of 10 μM (10 μL volume). After a preprogrammed hot start cycle (3 min at 95°C), parameters for PCR amplification were 15 s at 95°C and 60 s at 60°C with cycles repeated 45 times. mRNA levels of TLR4, and RAGE were tested (CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System; Bio-Rad). Fold differences in gene expression were calculated after normalization to β-actin and expressed as the relative mRNA concentration ± SEM. Table 1 depicts the primer pair sequences.

Table 1.

Nucleotide Sequence of the Specific Primers Used for Polymerase Chain Reaction Amplification

| Gene | Nucleotide sequence | Primer | GenBank |

|---|---|---|---|

| mβ-actin | 5′-GAT TAC TGC TCT GGC TCC TAG C-3′ | F | NM_007393.3 |

| 5′-GAC TCA TCG TAC TCC TGC TTG C-3′ | R | ||

| TLR4 | 5′-CCT GAC ACC AGG AAG CTT GAA-3′ | F | NM_021297.2 |

| 5′-TCT GAT CCA TGC ATT GGT AGG T-3′ | R | ||

| RAGE | 5′-GCT GTA GCT GGT GGT CAG AAC A-3′ | F | NM_007425.2 |

| 5′-CCC CTT ACA GCT TAG CAC AAG TG-3′ | R |

F, forward; R, reverse.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Mice from both treatment groups (n = 5 mice/group/time) were sacrificed on 3 and 5 days p.i. and uninfected and infected corneas collected. Each sample was homogenized in 500 μL PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 in a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 5 min. An aliquot of each supernatant was assayed in duplicate by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for protein levels of IL-1β, CXCL2, TNF-α, and IL-6 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN.) ELISA kits were run per the manufacturer's instructions; assay sensitivities were 2.31 pg/mL (IL-1β), <1.5 pg/mL (CXCL2), 1.88 pg/mL (TNF-α), and 1.6 pg/mL (IL-6).

Western blot

Corneas were harvested from mice treated with PBS or Box A at 3 and 5 days p.i. Pooled samples were suspended in PBS containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (ThermoFisher, Rockford, IL), sonicated, and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 20 min. Total protein was determined (Micro BCA protein kit; ThermoFisher). Total protein samples (RAGE = 30 μg; TLR4 = 40 μg) were run on SDS-PAGE in Tris-glycine-SDS buffer and electro-blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking for 1 h in 5% MTBST (TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat milk), membranes were probed with primary antibodies: rabbit anti-mouse TLR4 (1:80; Abcam Cambridge, MA) and rabbit anti-mouse RAGE (1:1,000; Abcam) in 3% BSA TBST overnight at 4°C. After 3 washes with TBST, the membranes were incubated with HRP conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) diluted in 5% MTBST (TLR4) or 3% BSA TBST (RAGE) at room temperature for 2 h. Bands were developed with Supersignal West Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate (ThermoScientific), visualized using a Kodak image station 4000R imaging system (Carestream Health, Inc., Rochester, NY), and normalized to β-actin and intensity quantified using AlphaView software.

Immunofluorescence staining of infected human corneas

Immunofluorescence was performed as described before.16 Corneal samples were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and 3 μm sections were cut. Nonspecific staining was blocked using normal goat serum diluted 1:100 in PBS. Tissue proteolysis was performed by treating the tissue with 0.1% protease XIV (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 0.05 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.6. After washing in EDTA buffered saline (pH 7.6), sections were incubated with monoclonal rabbit anti-human HMGB1 (1:350), TLR4 (1:50), RAGE (1:100), and TNF-α (1:100) antibodies (Abcam) overnight at 4°C. This was followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated affinipure goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:100; Millipore, Burlington, MA) for 1.5 h at room temperature. Isotype-matched IgG was used as a negative control. Images were captured with a Zeiss Axiovert microscope at 40 × magnification.

Immunofluorescent co-localization of HMGB1 with TLR4 or RAGE

Eyes were enucleated (n = 3/group/time) at 3 and 5 days p.i. from Box A or PBS-treated mice, immersed in 0.01M PBS, embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek; Miles, Elkhart, IN), and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Twelve micrometer sections were cut, mounted to poly-l-lysine-coated glass slides, and stored at 37°C overnight. Following a 2 min fixation in acetone at −20°C, slides were blocked with 0.01M PBS containing 2.5% BSA, and goat IgG (1:100; Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for 30 min at room temperature. To localize HMGB1, sections were incubated for 1 h with a 1:100 dilution of rabbit anti-HMGB1 (Cell Signaling Technology). Sections also were incubated with either rat anti-mouse RAGE (1:100; Abcam) antibody or rat anti-mouse TLR4/MD2 (1:100; Abcam) to detect co-localization with HMGB1. Incubation in the secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Invitrogen) for HMGB1 and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rat (Invitrogen) for RAGE or TLR4/MD2 at a dilution of 1:1,500 for 1 h followed. To label cell nuclei, coverslips were mounted to the slides using ProLong Gold anti-fade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen). Controls were similarly treated, but primary antibodies were replaced with naive IgG from the same host animal. Sections were visualized and digital images captured using a Leica TCS SP 8 confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL).

Statistical analysis

The difference in clinical score between 2 groups was analyzed by the Mann–Whitney U test (GraphPad Prism, San Diego, CA). An unpaired, 2-tailed Student's t-test determined significance for all other experiments (MPO, plate count, RT-PCR, TLR4, and RAGE protein expression and ELISA). For each test, P < 0.05 was considered significant; data are shown as mean ± SEM. Experiments were repeated at least once for reproducibility.

Results

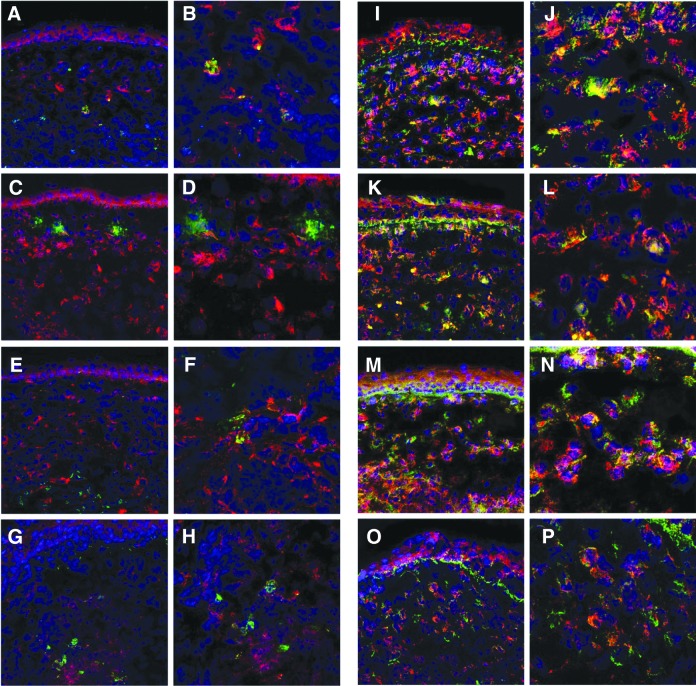

Immunohistochemistry of human cornea

Staining for HMGB1, TLR4, RAGE, and TNF-α was observed in P. aeruginosa-infected human corneas compared with no staining in normal corneas that were obtained from eye enucleation (Fig. 1A–H), substantiating their presence in human keratitis. HMGB1 staining in the infected cornea was intense, primarily localized to the epithelium, but some staining was seen in the superficial stroma just beneath the epithelium (Fig. 1B). Staining for TLR4 (Fig. 1D) was intense in the epithelium, but it was also detected in the superficial to mid stroma. RAGE (Fig. 1F) staining was spotty and less intense in the epithelium, with light stromal staining. TNF-α (Fig. 1H) staining was less intense and was primarily in the epithelium, but staining also was seen in the stroma and endothelium. No staining for each of the molecules tested: HMGB1 (Fig. 1A), TLR4 (Fig. 1C), RAGE (Fig. 1E), or TNF-α (Fig. 1G) was detected in normal cornea (Fig. 1A, C, G, E) nor in isotype-matched IgG negative controls (data not shown), which appeared similar to the normal tissue shown.

FIG. 1.

Immunohistochemistry for HMGB1, TLR4, RAGE, and TNF-α in human cornea. Immunostaining of normal and Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infected corneas from human patients showed expression of HMBG1 (B), TLR4 (D), RAGE (F), and TNF-α (H) in corneas infected with P. aeruginosa when compared with similarly processed normal cornea (A, C, E, G). HMGB1, high mobility group box 1.

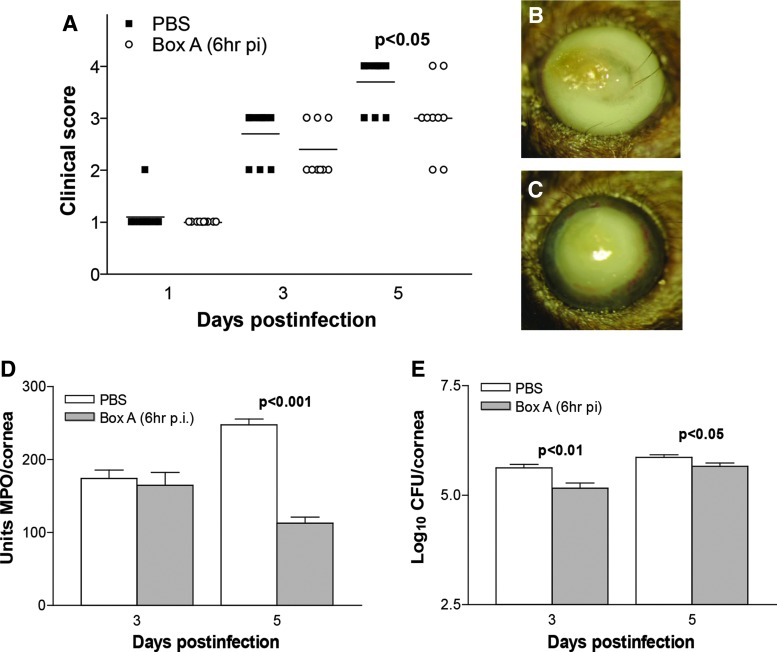

Box A prophylactic treatment

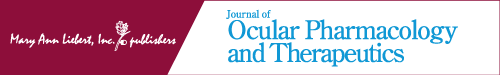

Infected corneas of Box A versus PBS-treated mice, showed improved disease outcome (Fig. 2A) with significantly reduced clinical scores at 3 (P < 0.01) and 5 (P < 0.001) days p.i. No significant difference in clinical scores was seen between groups at 1 day p.i. Representative photographs taken with a slit lamp camera (Fig. 2B, C) illustrated the reduced opacity evident in the Box A (+2, Fig. 2C) versus PBS (+4, Fig. 2B)-treated mice.

FIG. 2.

Disease response following Box A treatment. Clinical scores (A) showed that treatment with Box A versus PBS resulted in significantly less disease at 3 and 5 days p.i. with no difference between groups at 1 day p.i. (n = 10/group/time). Photographs taken with a slit lamp camera of infected corneas of PBS (B, +4) and Box A (C, +2)-treated mice illustrate the disease response at 5 days p.i. MPO assay (D) to enumerate neutrophils in cornea after infection showed a significant reduction in these cells at both 3 and 5 days p.i. after Box A versus PBS treatment. Bacterial counts (E) show a reduction in viable bacteria in the cornea of Box A versus PBS-treated mice at 3 and 5 days p.i. The difference in clinical scores was analyzed by the Mann–Whitney U test. An unpaired, 2-tailed Student's t-test determined significance for MPO assay and plate count data. P < 0.05 was considered significant; data are shown as mean ± SEM. PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; p.i., postinfection; MPO, myeloperoxidase.

Neutrophil infiltration and viable bacterial plate count

MPO assay (Fig. 2D) revealed a significant decrease in neutrophil infiltration in infected corneas at 3 (P < 0.05) and 5 (P < 0.0001) days p.i. after Box A versus PBS prophylactic treatment. Viable bacterial load was also reduced significantly (Fig. 2E) in the corneas of the Box A versus PBS group at 3 and 5 days p.i. (P < 0.05 for both).

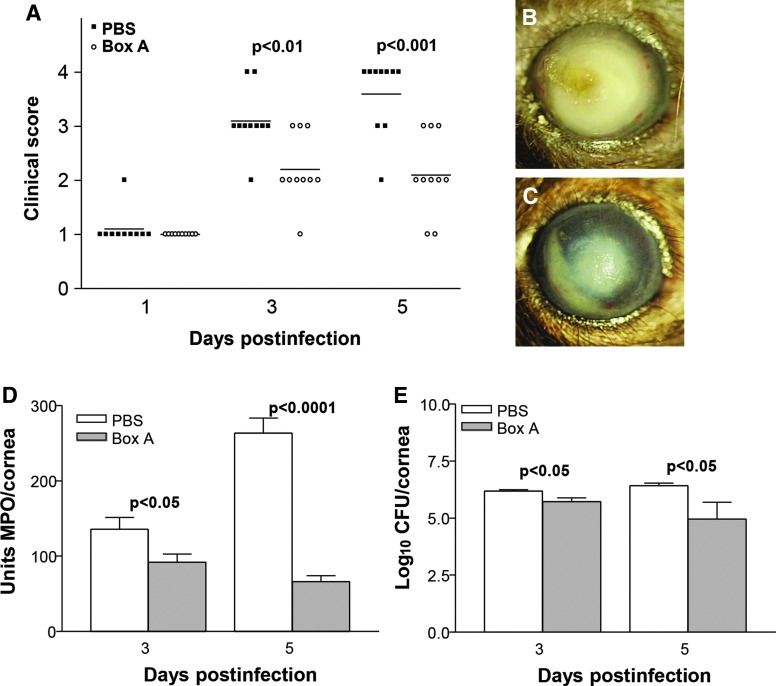

Box A effects on TLR4 and RAGE

Box A versus PBS treatment reduced corneal mRNA (Fig. 3A, B) and protein (Fig. 3C–F) levels of TLR4 and RAGE. At 5 days p.i., relative mRNA levels were significantly reduced for TLR4 (Fig. 3A, P < 0.01) and RAGE (Fig. 3B, P < 0.001) after Box A treatment. TLR4 and RAGE mRNA levels were not different between groups (Fig. 3A, B) in the uninfected, normal mouse cornea (N). Relative corneal protein expression of TLR4 and RAGE was quantified using western blot [Fig. 3E (TLR4), Fig. 3F (RAGE)]. At 3 days p.i. TLR4 and RAGE protein levels were slightly higher (Fig. 3C–F), but not significant for Box A versus PBS groups. But at 5 days p.i., Box A treatment reduced corneal protein expression of TLR4 (P < 0.001, Fig. 3C, E) and RAGE (P < 0.01, Fig. 3D, F). A significant reduction in protein expression also was seen for TLR4 (P < 0.001, Fig. 3C) and RAGE (Fig. 3D, P < 0.01) in uninfected, normal corneas (N) after Box A treatment.

FIG. 3.

RT-PCR and western blot for TLR4 and RAGE. Box A treatment significantly reduced corneal mRNA expression of TLR4 (A) and RAGE (B) at 5 days p.i. with no difference detected between groups in the uninfected, normal (N) cornea. Western blot and determination of relative protein expression by IDV analysis showed that Box A treatment reduced protein expression for TLR4 (C, E) and RAGE (D, F) in normal cornea and at 5 day p.i. No difference between treatment groups was seen at 3 days p.i. for either TLR4 or RAGE. An unpaired, 2-tailed Student's t-test determined significance for RT-PCR and protein expression data. P < 0.05 was considered significant; data are shown as mean ± SEM. IDV, integrated density value; RT-PCR, real-time polymerase chain reaction.

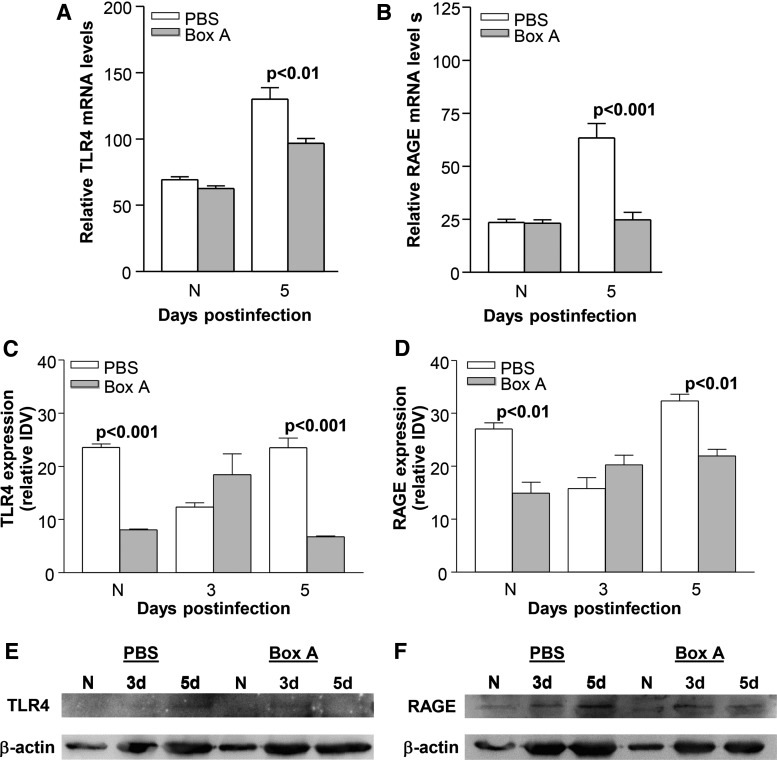

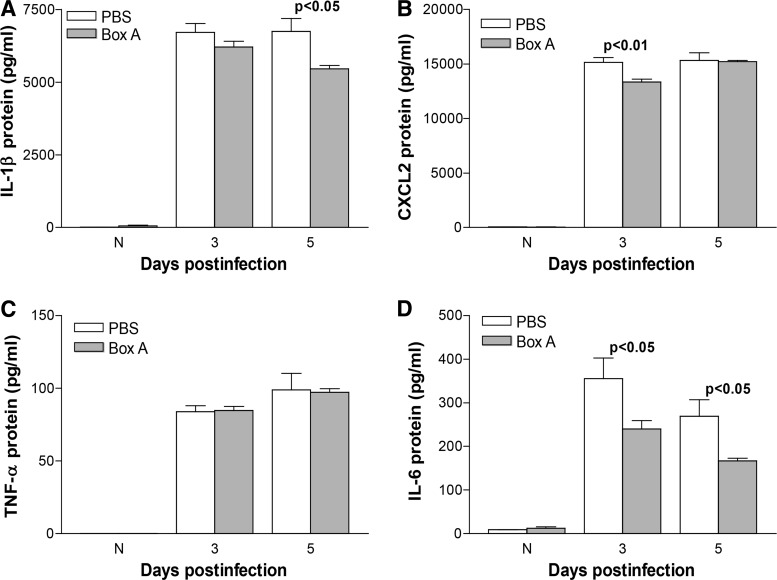

Box A effects expression of proinflammatory molecules

Corneal protein expression of IL-1β, CXCL2, TNF-α, and IL-6 was determined by ELISA after Box A versus PBS treatment. At 5 days p.i., Box A treatment significantly reduced protein levels of IL-1β (P < 0.001, Fig. 4A), CXCL2 (P < 0.001, Fig. 4B), and TNF-α (P < 0.01, Fig. 4C) but not IL-6 (Fig. 4D). For normal, uninfected cornea (N) and corneas harvested at 3 days p.i., no significant difference in protein expression was detected among any of the groups (Fig. 4A–D).

FIG. 4.

ELISA. Protein expression in the infected corneas of Box A versus PBS-treated mice for IL-1β (A), CXCL2 (B), and TNF-α (C) was significantly reduced at 5 days p.i. No difference in protein levels was detected between 3 days p.i. or normal, uninfected corneas. No significant difference was detected between treatment groups at any time tested for IL-6 (D). An unpaired, 2-tailed Student's t-test determined significance for ELISA data. P < 0.05 was considered significant; data are shown as mean ± SEM. ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

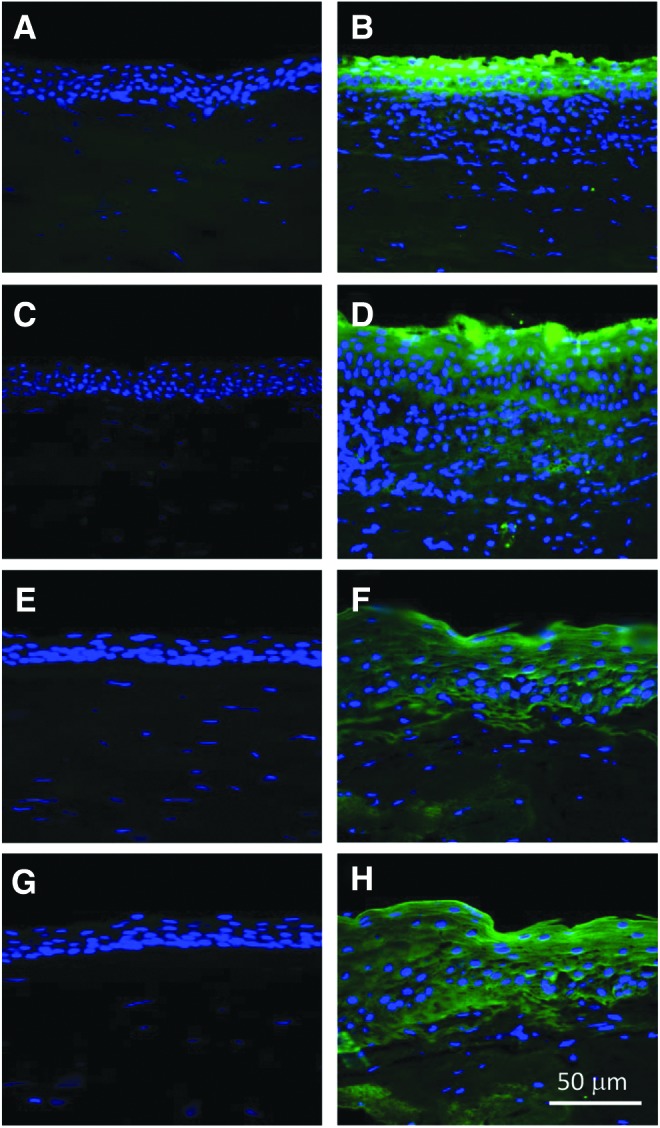

Effect of Box A on HMGB1 co-localization with TLR4 or RAGE

At 3 and 5 days p.i., immunohistochemical staining was done on the infected corneas of mice treated with Box A or PBS (Fig. 5A–P). Dual labeling was used to stain HMGB1 (red) and TLR4 or RAGE (each green) to detect their co-localization (yellow) with HMGB1. Modest HMGB1 and TLR4 (Fig. 5A–H) co-localization was detected at 3 and 5 days p.i. only in the PBS-treated group (3 days p.i. = Fig. 5A, B; 5 days p.i. = Fig. 5E, F). For HMGB1 and RAGE (Fig. 5I–P) a similar co-localization pattern for both treatment groups was seen at 3 (PBS = Fig. 5I, J; Box A = Fig. 5K, L) days p.i. However, at 5 days p.i., co-localization of HMGB1 with RAGE (Fig. 5M–P) was seen only after PBS (Fig. 5M, N) treatment.

FIG. 5.

Immunohistochemistry for HMGB1 and TLR4 or RAGE. Dual immunostaining of infected corneas from Box A versus PBS-treated mice showed a modest pattern of co-labeling (yellow) of HMBG1 (red) with TLR4 (green) at 3 (A, B) and 5 (E, F) days p.i. only in the PBS-treated group. In contrast Box A treatment resulted in little to no colocalization at 3 (C,D) or 5 (G,H) days p.i. A similar pattern of co-localization (yellow) was seen for HMGB1 and RAGE at 3 days p.i. (I–L), but co-localization of HMGB1 and RAGE at 5 days p.i, was seen only in the PBS-treated corneas (M, N), but not in the Box A treated group (O,P). Magnification: 230 × (A, C, E, G, I, K, M, O), magnification: 460 × (B, D, F, H, J, L, N, P).

Therapeutic treatment with Box A

The therapeutic efficacy of Box A was tested with treatment beginning at 6 h p.i. The infected cornea of Box A versus PBS-treated mice showed fewer perforated corneas (Fig. 6A), reflected by reduced clinical score at 5 days p.i. (P < 0.05). No significant difference in clinical scores was seen between groups at 1 and 3 days p.i. Representative photographs taken with a slit lamp camera (Fig. 6B, C) illustrate corneal perforation in the PBS-treated group (+4, Fig. 6B), and dense opacity (+3, Fig. 6C) after Box A treatment. Box A significantly reduced the neutrophil infiltrate (only at 5 days p.i., P < 0.001, Fig. 6D) and viable bacterial load (Fig. 6E) in the infected cornea at 3 (P < 0.01) and 5 (P < 0.05) days p.i. ELISA was used to quantify the corneal protein expression levels of IL-1β (Fig. 7A), CXCL2 (Fig. 7B), TNF-α (Fig. 7C), and IL-6 (Fig. 7D) at 3 and 5 days p.i. For Box A versus PBS groups, a significant reduction in protein levels was seen for IL-1β (Fig. 7A, P < 0.05, only at 5 days p.i.), CXCL2 (Fig. 7B, P < 0.01, only at 3 days p.i.), and IL-6 (Fig. 7D, P < 0.05, both 3 and 5 days p.i.). TNF-α protein expression did not differ significantly between groups at any time tested (Fig. 7C). For the uninfected, normal corneas (N), no differences in protein expression for any cytokines was detected between the Box A and PBS groups.

FIG. 6.

Disease response following therapeutic Box A treatment. Clinical score (A) showed that treatment with Box A versus PBS resulted in modest, but significantly fewer perforations at 5 days p.i. with no difference between groups at 1 and 3 days p.i. (n = 10/group/time). Photographs taken with a slit lamp camera of infected corneas of PBS (B, +4) and Box A (C, +3)-treated mice illustrated that fewer Box A-treated corneas perforated at 5 days p.i. but that these corneas were densely opaque. MPO assay (D) showed a significant reduction in corneal neutrophils only at 5 days p.i. after Box A versus PBS treatment. Bacterial counts (E) showed a reduction in viable bacteria (less than 1 log) in the cornea of Box A versus PBS-treated mice at both 3 and 5 days p.i. The difference in clinical scores was analyzed by the Mann–Whitney U test. An unpaired, 2-tailed Student's t-test determined significance for MPO assay and plate count data. P < 0.05 was considered significant; data are shown as mean ± SEM.

FIG. 7.

ELISA (therapeutic treatment). Protein expression in the infected corneas of Box A versus PBS-treated mice for IL-1β (A) was reduced at 5 days p.i. with no difference at 3 days p.i. CXCL2 (B) protein levels were reduced by Box A treatment at 3 days p.i., but not at 5 days p.i. Box A treatment significantly reduced IL-6 (D) protein at both 3 and 5 days p.i. No significant difference was detected between treatment groups at any time tested for TNF-α (C). No difference in protein levels were detected between normal, uninfected corneas. An unpaired, 2-tailed Student's t-test determined significance for ELISA data. P < 0.05 was considered significant; data are shown as mean ± SEM.

Discussion

In this study we tested a targeted therapy, using the HMGB1 antagonist Box A to treat keratitis induced by P. aeruginosa. Extracellular HMGB1 initiates diverse proinflammatory responses by interacting with cell surface receptors such as TLR2, TLR4, and RAGE.17–23 Specifically, during sepsis and sterile injury, binding of HMGB1 to TLR4 and RAGE stimulates chemotaxis and NF-κB signaling pathways19,24 upregulating cytokine production (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β). In previous studies from this laboratory, various anti-HMGB1 treatment strategies were used in experimental animal models of P. aeruginosa keratitis, and showed beneficial effects.6,25 For example, we have shown that siRNA mediated gene silencing,7 neutralizing anti-HMGB1 antibody7 and glycyrrhizin (GLY)13,26–28 all improve keratitis.

In other models, such as alkali-induced corneal neovascularization (CNV) and inflammation-induced lymphangiogenesis, HMGB1/TLR4-mediated downstream signaling pathways promote CNV22 and lymphangiogenesis.23 To prevent the binding of HMGB1 to TLR or RAGE, Box A was used as a blocking agent and found to competitively block the binding of HMGB1 to its cell surface receptors (TLR4 and RAGE).6,10 However, except for one in vitro study29 most studies only tested the consequent reduced expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines downstream of HMGB1/TLR4 or RAGE pathways.6,30 That in vitro study29 focused on the effect of Box A on LPS-induced intestinal inflammation using a transwell co-culture system, which contained Box A overexpressing SW480 cells and human monocytic (THP-1) cells stimulated with LPS. This study revealed that Box A had an effect on the HMGB1/TLR4 and LPS/TLR4 pathways and significantly downregulated mRNA and protein levels of HMGB1 and TLR4.

In the in vivo study reported herein, we provide evidence that treatment with Box A significantly reduced corneal mRNA and protein (western blot) levels of TLR4 and RAGE at 5 days p.i., agreeing with in vitro study above.29 It is highly likely that this effect is due to blocking ligand binding by Box A since it has been reported that Box A has a higher binding affinity for TLR431 and RAGE32 compared to other parts of the molecule. Consistent with the Box A-mediated reduction in TLR4 and RAGE levels (mRNA and protein), at 5 days p.i., immunostaining showed that co-localization of HMGB1 with TLR4 or RAGE was detected only in the PBS-treated group. This provides further evidence that Box A prevents the binding of HMGB1 to cell surface receptors, but this effect may be time dependent as it was not observed at 3 days p.i. It is possible, but not tested in our model, that this delayed effect of Box A is linked to the delayed kinetics (18–72 h) of extracellular HMGB1 release during sepsis.4 Treatment with Box A also reduced corneal TLR4 and RAGE, significantly in the uninfected, untreated contralateral eye. This is most likely due to the presence of Box A in the systemic circulation after subconjunctival and intraperitoneal injections. This Box A present in systemic circulation may block the activation of HMGB1/TLR4 and HMGB1/RAGE-mediated intracellular signaling pathways and corresponding feedback loops that govern the cell surface expression of those receptors. However, it is reported that systemic effects to contralateral eye may depend on the mode of action of test compound in ocular tissue and/or its long half-life in systemic circulation.33 In this study, it is important to note that protein expression of only TLR4 and RAGE, but not other molecules tested were reduced significantly in the contralateral eye. As mentioned above this may be mainly because of the mode of action of Box A, which targets the binding of HMGB1 to its frontend receptors TLR4 and RAGE.

It is also reported that HMGB1/TLR4 or RAGE-coupled signaling cascades trigger autocrine and paracrine feedback mechanisms to stimulate the production of cytokines and chemokines.3,34–37 Blocking these interactions by Box A showed beneficial effects on regulating HMGB1-mediated proinflammatory responses in vivo in different experimental animal models,10,30 and as reported herein, in keratitis. Specifically, prophylactic treatment with Box A significantly reduced protein levels of IL-1β, CXCL2, and TNF-α (only at 5 days p.i.); and the neutrophil infiltrate (3 and 5 days p.i.). These reductions are significant because TNF-α, released by activated macrophages and monocytes early during infection or sterile injury,38–41 together with IL-1β, CXCL2, and other proinflammatory molecules, can initiate, amplify, and sustain proinflammatory responses.42 Therapeutic treatment with Box A reduced perforation, but significant opacity was observed at 5 days p.i., despite the fact that reduction in the chemoattractant IL-1β (but not CXCL2 or TNF-α) and the neutrophil infiltrate was seen.

Prophylactic Box A treatment did not significantly change IL-6 levels, but disease outcome was better. Therapeutically, significant reduction of IL-6 protein levels with relatively high opacity in the Box A treated, infected cornea was observed. These disparate results are puzzling, but may reflect the timing of modifying IL-6 levels (earlier prophylactically and later therapeutically) leading to its beneficial or detrimental role after.43 In addition, the role of IL-6 in infection is controversial, as it can function as a pro or anti-inflammatory cytokine.42–44 Studies have shown a protective role for IL-6 in some models of P. aeruginosa-induced corneal infections.42,44–46

After prophylactic and therapeutic Box A treatments, viable bacterial count in the infected cornea was also reduced significantly. This reduction may be due to less bystander tissue damage in the Box A-treated infected cornea as a result of reduced neutrophil levels. Specifically, such reduction in bystander tissue damage can limit the food source and motility of P. aeruginosa in the cornea, which prevent bacterial spread. In addition, as an antagonist of HMGB1, Box A mediates the reduction in bacterial burden by downregulating the expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which are known to favor the growth of P. aeruginosa.47 However, compared with prophylactic, therapeutic treatment with Box A is less effective, and did not significantly reduce the opacity of the infected cornea and protein expression of CXCL2 and TNF-α at 5 days p.i. Instead, Box A therapeutic treatment led to elevated bacterial plate counts at 5 versus 3 days p.i. This indicates that disease may be merely delayed in the therapeutic model.

To confirm the importance of these studies to human disease, expression of HMGB1, TLR4, RAGE, and TNF-α was tested in human corneas infected with P. aeruginosa. Positive immunostaining for all of these molecules was seen only in the infected corneas, confirming their relevancy to clinical disease. Normal corneas that were obtained from eye enucleations did not express the molecules.

Overall, this study revealed that Box A shows some effect on reduction of keratitis through blocking the effects of HMGB1 and associated molecules (TLR4 and RAGE). However, comparatively, it fails to provide the benefits observed by targeting HMGB1 using a small triterpenoid molecule, GLY.13,26–28 Collectively, these latter studies have shown that either pre- or post-treatment approaches reduce bacterial plate count, neutrophil infiltrate, levels of HMGB1, and other proinflammatory molecules significantly with better disease outcome.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants R01EY016058 and P30EY004068 from the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, and by a Research to Prevent Blindness unrestricted grant in the Department of Ophthalmology, Visual and Anatomical Sciences/Kresge Eye Institute.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Parkkinen J., Raulo E., Merenmies J., et al. Amphoterin, the 30-kDa protein in a family of HMG1-type polypeptides. Enhanced expression in transformed cells, leading edge localization, and interactions with plasminogen activation. J. Biol. Chem. 268:19726–19738, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maher J.F., and Nathans D. Multivalent DNA-binding properties of the HMG-1 proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:6716–6720, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andersson U., and Tracey K.J. HMGB1 is a therapeutic target for sterile inflammation and infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 29:139–162, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang H., Yang H., Czura C.J., Sama A.E., and Tracey K.J. HMGB1 as a late mediator of lethal systemic inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 164:1768–1773, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang H., Bloom O., Zhang M., et al. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science. 285:248–251, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yang H., and Tracey K.J. Targeting HMGB1 in inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1799:149–156, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McClellan S., Jiang X., Barrett R., and Hazlett L.D. High-mobility group box 1: a novel target for treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. J. Immunol. 194:1776–1787, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li J., Kokkola R., Tabibzadeh S., et al. Structural basis for the proinflammatory cytokine activity of high mobility group box 1. Mol. Med. 9:37–45, 2003 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang H., Ochani M., Li J., et al. Reversing established sepsis with antagonists of endogenous high-mobility group box 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:296–301, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gong Q., Xu J.F., Yin H., et al. Protective effect of antagonist of high-mobility group box 1 on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Scand. J. Immunol. 69:29–35, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kokkola R., Li J., Sundberg E., et al. Successful treatment of collagen-induced arthritis in mice and rats by targeting extracellular high mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 activity. Arthritis Rheum. 48:2052–2058, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yuan H., Jin X., Sun J., et al. Protective effect of HMGB1 a box on organ injury of acute pancreatitis in mice. Pancreas. 38:143–148, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ekanayaka S.A., McClellan S.A., Barrett R.P., Kharotia S., and Hazlett L.D. Glycyrrhizin reduces HMGB1 and bacterial load in Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 57:5799–5809, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hazlett L.D., Moon M.M., Strejc M., and Berk R.S. Evidence for N-acetylmannosamine as an ocular receptor for P. aeruginosa adherence to scarified cornea. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 28:1978–1985, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Williams R.N., Paterson C.A., Eakins K.E., and Bhattacherjee P. Quantification of ocular inflammation: evaluation of polymorphonuclear leucocyte infiltration by measuring myeloperoxidase activity. Curr. Eye Res. 2:465–470, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jiang N., Zhao G., Lin J., et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase is involved in the inflammation response of corneal epithelial cells to Aspergillus fumigatus infections. PLoS One. 10:e0137423, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Park J.S., Gamboni-Robertson F., He Q., et al. High mobility group box 1 protein interacts with multiple Toll-like receptors. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 290:C917–C924, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chandrashekaran V., Seth R.K., Dattaroy D., et al. HMGB1-RAGE pathway drives peroxynitrite signaling-induced IBD-like inflammation in murine nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Redox. Biol. 13:8–19, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bertheloot D., and Latz E. HMGB1, IL-1alpha, IL-33 and S100 proteins: dual-function alarmins. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 14:43–64, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Zoelen M.A., Yang H., Florquin S., et al. Role of toll-like receptors 2 and 4, and the receptor for advanced glycation end products in high-mobility group box 1-induced inflammation in vivo. Shock. 31:280–284, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Agalave N.M., Larsson M., Abdelmoaty S., et al. Spinal HMGB1 induces TLR4-mediated long-lasting hypersensitivity and glial activation and regulates pain-like behavior in experimental arthritis. Pain. 155:1802–1813, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lin Q., Yang X.P., Fang D., et al. High-mobility group box-1 mediates toll-like receptor 4-dependent angiogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 31:1024–1032, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Han L., Zhang M., Wang M., et al. High mobility group box-1 promotes inflammation-induced lymphangiogenesis via toll-like receptor 4-dependent signalling pathway. PLoS One. 11:e0154187, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhao F., Fang Y., Deng S., et al. Glycyrrhizin protects rats from sepsis by blocking HMGB1 signaling. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017:9719647, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hazlett L.D., McClellan S.A., and Ekanayaka S.A. Decreasing HMGB1 levels improves outcome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis in mice. J. Rare. Dis. Res. Treat. 1:36–39, 2016 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ekanayaka S.A., McClellan S.A., Barrett R.P., and Hazlett L.D. Topical glycyrrhizin is therapeutic for Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 34:239–249, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peng X., Ekanayaka S.A., McClellan S.A., et al. Characterization of three ocular clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa: viability, biofilm formation, adherence, infectivity, and effects of glycyrrhizin. Pathogens. 6, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peng X., Ekanayaka S.A., McClellan S.A., et al. Effects of glycyrrhizin on a drug resistant isolate of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. EC Ophthalmol. 265–280, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang F.C., Pei J.X., Zhu J., et al. Overexpression of HMGB1 A-box reduced lipopolysaccharide-induced intestinal inflammation via HMGB1/TLR4 signaling in vitro. World J. Gastroenterol. 21:7764–7776, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gong W., Zheng Y., Chao F., et al. The anti-inflammatory activity of HMGB1 A box is enhanced when fused with C-terminal acidic tail. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010:915234, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. He M., Bianchi M.E., Coleman T.R., Tracey K.J., and Al-Abed Y. Exploring the biological functional mechanism of the HMGB1/TLR4/MD-2 complex by surface plasmon resonance. Mol. Med. 24:21, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. LeBlanc P.M., Doggett T.A., Choi J., et al. An immunogenic peptide in the A-box of HMGB1 protein reverses apoptosis-induced tolerance through RAGE receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 289:7777–7786, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Forrester J.V., Dick A.D., McMenamin P.G., Roberts F., and Pearlman E. The Eye—Basic Science in Practice. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders ltd. Elsevier; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tadie J.M., Bae H.B., Jiang S., et al. HMGB1 promotes neutrophil extracellular trap formation through interactions with Toll-like receptor 4. Am. J. Physiol. Lung. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 304:L342–L349, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huebener P., Pradere J.P., Hernandez C., et al. The HMGB1/RAGE axis triggers neutrophil-mediated injury amplification following necrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 125:539–550, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Andersson U., Wang H., Palmblad K., et al. High mobility group 1 protein (HMG-1) stimulates proinflammatory cytokine synthesis in human monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 192:565–570, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang H., Yang H., and Tracey K.J. Extracellular role of HMGB1 in inflammation and sepsis. J. Intern. Med. 255:320–331, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Manderson A.P., Kay J.G., Hammond L.A., Brown D.L., and Stow J.L. Subcompartments of the macrophage recycling endosome direct the differential secretion of IL-6 and TNFalpha. J. Cell. Biol. 178:57–69, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Beutler BA. The role of tumor necrosis factor in health and disease. J. Rheumatol. Suppl. 57:16–21, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Arango Duque G., and Descoteaux A. Macrophage cytokines: involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front. Immunol. 5:491, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kernacki K.A., Goebel D.J., Poosch M.S., and Hazlett L.D. Early cytokine and chemokine gene expression during Pseudomonas aeruginosa corneal infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 66:376–379, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hazlett L.D. Corneal response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 23:1–30, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Akira S., Hirano T., Taga T., and Kishimoto T. Biology of multifunctional cytokines: IL 6 and related molecules (IL 1 and TNF). FASEB J. 4:2860–2867, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zahir-Jouzdani F., Atyabi F., and Mojtabavi N. Interleukin-6 participation in pathology of ocular diseases. Pathophysiology. 24:123–131, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cole N., Krockenberger M., Bao S., et al. Effects of exogenous interleukin-6 during Pseudomonas aeruginosa corneal infection. Infect. Immun. 69:4116–4119, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Carnt N.A., Willcox M.D., Hau S., et al. Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms of interleukins-1beta, -6, and -12B with contact lens keratitis susceptibility and severity. Ophthalmology. 119:1320–1327, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kanangat S., Meduri G.U., Tolley E.A., et al. Effects of cytokines and endotoxin on the intracellular growth of bacteria. Infect. Immun. 67:2834–2840, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]