Abstract

Despite the high prevalence of osteoporosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients, the fracture risk prediction tools are not routinely undertaken in the management of COPD. We quantified fracture risk using a validated risk prediction tool (Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX®)) and determined potential bone-protection treatment needs in patients with advanced COPD. The 10-year probability of major osteoporotic or hip fracture was calculated using the FRAX tool in a cohort of patients attending a hospital complex COPD service. Patients were identified to be at low, intermediate and high risk based on their FRAX scores, in accordance with the National Osteoporosis Guideline Group recommendations, to assess the number of patients requiring bone mineral density (BMD) testing or bone protection therapy. Two hundred forty-seven patients [mean (standard deviation (SD)) age 66 (9.1) years, 26% current smokers, 40% women and median (interquartile range (IQR)) Medical Research Council (MRC) breathlessness scale 4 (0)] had a 10-year probability of 9.5% (6.1) and 3.8% (4.6) for major osteoporotic and hip fractures, respectively. Thirty-six percentage of patients were identified to be at intermediate risk of developing fragility fracture, requiring BMD assessment, while 9% were at high risk, requiring treatment. Thirty-two percentage of high-risk patients were on bisphosphonates. The FRAX score can be used to assess the fracture risk within the COPD cohort and assist with decision-making about BMD measurement and provision of bone protection therapy.

Keywords: COPD, osteoporotic fractures, fracture risk, FRAX®, co-morbidities

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is associated with a number of systemic co-morbidities, the presence of which is known to be predictive of poorer clinical outcomes.1 One such co-morbidity is osteoporosis, which has been shown to have a higher prevalence in COPD (compared with age-matched healthy individuals).2 The impact of osteoporosis-induced fractures can be significant in this cohort, as 1-year mortality following hip fractures is higher in COPD than in non-COPD patients.3 Early detection and treatment of osteoporosis with calcium and vitamin D supplementation and bisphosphonates as first-line medications reduces the risk of fragility fractures.4,5 Guidance from Royal College of Physicians (RCP) had previously recommended measuring bone mineral density (BMD), using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), to assist physicians in identifying individuals at risk of developing fractures.6 It has since become apparent that several clinical risk factors for osteoporosis are better predictors than BMD alone.7 As a result, updated guidance has advised the use of clinical risk prediction tools to identify high-risk patients8,9 and support clinical decision-making.

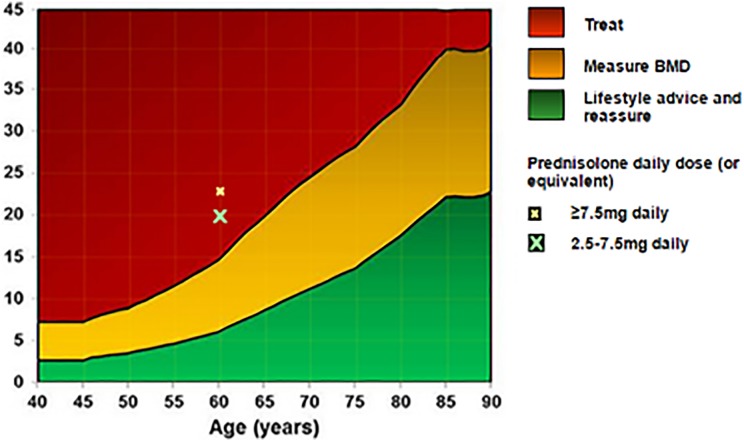

The Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX®) is a clinical risk prediction tool that can be used to predict the 10-year risk of osteoporotic fractures by incorporating clinical indices associated with fracture risk, with or without DXA measures of BMD.10,11 The UK National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG) use the scores calculated using the FRAX tool to characterize patients into low-, intermediate- and high-risk groups for fragility fracture, according to their age (Figure 1). They base treatment recommendations on these risk categories, advising conservative management for low-risk, DXA scanning (and recalculation of FRAX scores) for intermediate-risk and pharmacological intervention for high-risk patients.9

Figure 1.

FRAX® calculation tool. It calculates the 10-year probability of developing major osteoporotic and hip fractures (%). The image shows how the values of major osteoporotic fractures are categorized to aid decision-making of treatment. FRAX: Fracture Risk Assessment; BMD: bone mineral density.

Despite the availability of such validated risk prediction tools, assessment of fracture risk is not undertaken frequently in COPD patients (in primary or secondary care settings), which may result in under-treatment12,13 and underutilization of DXA scanning.

The aim of this study was to determine osteoporotic fracture risk using the FRAX tool in a cohort of patients with advanced COPD, attending a hospital complex COPD clinic. In addition, we aimed to determine the disease associations with fracture risk and the relationship between the FRAX scores and the recorded BMD. Finally, we estimated the number of patients who would require DXA scanning to refine risk prediction and the number that were appropriately treated with bone protection therapy.

Materials and methods

Patient population and study design

Patients attending a specialist complex COPD outpatient service at Glenfield Hospital, Leicester, UK, underwent a structured annual assessment, detailing disease burden across domains of breathlessness/exercise limitation, exacerbations, co-morbidity screening and prognostic indicators (termed a ‘comprehensive respiratory assessment’ (CRA)).14 Local guidance for referral to the clinic is forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) < 50% predicted, in addition to one of two or more admissions to hospital with acute exacerbations of COPD in 1 year; severe disability (Medical Research Council (MRC) score 4 or worse); current smokers and low body mass index (BMI) (<21 kg/m2) or unexplained weight loss (>5% in 6 months) or established respiratory failure (partial pressure of oxygen [PO2] < 8 in stable state). Patients provided informed consent for their data to be used for research purposes. The research was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Clinical measurements

Clinical information collected during the CRA included patient’s symptom burden, lung function, exacerbation frequency and number of COPD-related hospitalizations per year, whether they were on long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT), smoking status, alcohol intake, medication and history of co-morbidities. Patients also routinely underwent DXA scanning to measure body composition and physical performance assessment if deemed clinically feasible and appropriate. DXA scans were not performed in patients who were unable to lie flat for the procedure or in whom it was deemed inappropriate due to poor prognosis.

Calculation of fracture probability using FRAX tool

The FRAX tool was used to calculate the 10-year probability of major osteoporotic and hip fractures by entering data in the following fields on the online reference tool: age, gender, weight (kg), height (cm), smoking status, whether patients were on long-term oral glucocorticoids or had more than three exacerbations in a year, requiring 5-day courses of 30 mg of prednisolone (as a surrogate for cumulative dose of more 450 mg), a history of previous fragility fractures, whether they had parents with hip fractures, whether they had rheumatoid arthritis or secondary osteoporosis (type 1 or insulin-treated diabetes, osteogenesis imperfecta, untreated long-standing hypothyroidism, hypogonadism or premature menopause, chronic malnutrition or chronic liver disease) and whether they consumed more than three units of alcohol per day.11 Data for history of fragility fractures and family history of hip fractures were not routinely recorded in clinic, and so unless actually recorded, these options were marked as “no” for the purposes of this analysis. Risk prediction scores were generated without including BMD data. Patients were categorized into low-, intermediate- and high 10-year risk of major osteoporotic fracture in accordance with NOGG guidance (Figure 1).

Incremental shuttle walking test

This is a field test of maximal, symptom-limited walking performance. Patients were required to walk between two cones in time to a set of auditory beeps, progressively increasing their speed to the beep. They continued this until they were too breathless or could not keep up with the beeps. The number of metres travelled during the test was recorded.15

Isometric quadriceps strength

Patients sat in a chair having the ankle of their dominant leg connected to a strain gauge. Patients performed isometric quadriceps contractions of between 5 seconds and 10 seconds duration. The force produced was recorded, and the best quadriceps maximal voluntary contraction (QMVC) was then expressed as a function of the patient’s BMI.There was a gap of 30–60 seconds between each contraction to allow time to recover from each effort.16

Spirometry

Spirometry was performed in a seated position by standardized techniques (Vitalograph, Model, R; Vitalograph Ltd, Buckingham, UK) in the lung function departments of the Glenfield Hospital, Leicester. FEV1 values were represented as percentage of predicted values calculated from the European Respiratory Society regression equations.17

Body composition

Whole body DXA, performed in the supine position (Lunar Expert-XL Bone Densitometer; Lunar Radiation Corporation, Madison, Wisconsin, USA), was offered to the cohort to derive body composition measurements. Total soft tissue mass, bone mass, lean mass and fat mass were derived using software provided by the manufacturer.

Appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASM), that is, the sum of the muscle mass of both upper limbs and lower limbs,18 was used to obtain skeletal muscle index (SMI) as ASM/height2.

Fat-free muscle (FFM) was calculated as the sum of lean mass and bone mineral mass.18 Fat-free muscle index (FFMI) was subsequently determined as FFM/height2.

Body weight was measured using digital scales (Seca, UK) to the nearest 100 g. Height was measured to the nearest centimetre using a wall-mounted stadiometer. These measurements were used to calculate the BMI as weight/height2 (kg/m2).

Statistical analysis

To determine the relationship between COPD characteristics with osteoporotic fracture risk, the cohort was divided into quartiles, based on the FRAX scores of major osteoporotic fractures and grouped against the respiratory disease characteristics. One-way analysis of variance was used to identify significant differences for quantitative parameters, and the χ 2 test was used for discrete variables, which were represented as percentages.

To identify the proportion of patients who required DXA scans or were appropriately treated with bone protection, the cohort was categorized into low-, intermediate- and high-risk groups, according to the FRAX scores. The number of patients on bisphosphonates and vitamin D within each group was recorded. The reason for categorizing patients into three groups as opposed to quartiles was to comply with NOGG guidelines, outlining management options based on the FRAX score thresholds.9 For patients in the intermediate category, NOGG advise measuring femoral neck BMD and then recalculating the probability of fragility fractures. In this study, the whole body instead of hip BMD was measured, and so recalculation of fracture risk was not possible. As a result, patients in the intermediate-risk group with T scores <−2.35, as calculated from the whole body DXA scans, were defined as osteoporotic and reclassified into the high-risk group.19

Results

Data on 247 patients who underwent a CRA were recorded, with 209 patients having whole body DXA scans. The mean (standard deviation (SD)) age was 66 (9.1) years, 26% were current smokers, 40% were female and the median (interquartile range (IQR)) MRC breathlessness scale was 4 (0).

The characteristics of the COPD cohort are presented in Table 1. The mean (SD) 10-year risk was 9.5% (SD 6.1) and 3.8% (SD 4.6) for major osteoporotic and hip fractures, respectively, for the whole population. There was a significant difference between quartiles in the measure of markers of COPD disease progression (FEV1, incremental shuttle walk test, exacerbations per year, on %LTOT and QMVC), proportion of patients on maintenance steroids and body composition (BMI, FFMI and SMI).

Table 1.

Risk factors associated with risk of major osteoporotic fractures.a

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRAX® major osteoporotic fracture (%) | 4.4 (0.9) (n = 62) | 6.6 (0.9) (n = 61) | 8.9 (0.7) (n = 57) | 17.2 (0.6) (n = 67) | 9.5 (6.1) (n = 247) | p Value |

| FRAX hip fracture (%; n = 247) | 0.8 (0.5) | 1.8 (0.9) | 3.3 (1.5) | 8.9 (6.0) | 3.8 (4.6) | <0.001 |

| COPD-related characteristics | ||||||

| FEV1 (L; n = 247) | 0.97 (0.45) | 0.88 (0.35) | 0.76 (0.26) | 0.65 (0.23) | 0.82 (0.36) | <0.001 |

| Current smokers (%; n = 247) | 31 | 18 | 33 | 24 | 26 | 0.45 |

| Exacerbations in previous year (n = 245) | 3 (3.3) | 5 (4.8) | 5 (3.6) | 6 (5.3) | 5 (4.4) | 0.003 |

| COPD-related hospitalizations in previous year (n = 247) | 1 (0.98) | 1 (2.88) | 1 (1.23) | 1 (1.88) | 1 (1.63) | 0.148 |

| On maintenance steroids: yes (%; n = 247) | 5 | 11 | 21 | 10 | 11 | 0.04 |

| On home oxygen: yes (%; n = 247) | 27 | 38 | 30 | 51 | 37 | 0.03 |

| ISWT (m; n = 128) | 213 (142) | 163 (83) | 133 (78) | 87 (45) | 158 (110) | <0.001 |

| Quadriceps strength (kg; n = 214) | 24.4 (9.7) | 19.1 (7.3) | 18.9 (5.3) | 12.9 (4.5) | 18.9 (8.2) | <0.001 |

| Body composition | ||||||

| BMI (n = 247) | 28.9 (7.6) | 25.3 (6.0) | 25.2 (6.8) | 23.3 (6.4) | 25.7 (7.0) | <0.001 |

| FFMI (kg/m2; n = 208) | 17.8 (2.7) | 16.9 (2.3) | 16.3 (2.5) | 14.9 (1.9) | 16.4 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| SMI (kg/m2; n = 209) | 6.8 (1.2) | 6.5 (1.1) | 5.9 (1.0) | 5.4 (0.9) | 6.2 (1.2) | <0.001 |

FRAX: Fracture Risk Assessment; n: total number in that cohort; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in the first second; ISWT: incremental shuttle walk test; BMI: body mass index; FFMI: fat-free mass index; SMI: skeletal muscle index; SD: standard deviation.

aThe cohort is divided into quartiles, based on the FRAX 10-year major osteoporotic fracture risk, with quartile 1 being at the lowest risk and quartile 4 at the highest risk. Data are mean (SD).

The mean (SD) T scores and BMD for the COPD cohort were −0.7 (1.74) and 1.122 g/cm2 (0.13 g/cm2), respectively. Significant differences in the whole body BMD and T score between FRAX risk quartiles were observed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relationship between 10-year probability of major osteoporotic fractures and bone mineral density.a

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRAX® major osteoporotic fracture (%) | 4.4 (0.9) (n = 62) | 6.6 (0.9) (n = 61) | 8.9 (0.7) (n = 57) | 17.2 (0.6) (n = 67) | 9.5 (6.1) (n = 247) | p Value |

| BMD (g/cm2; n=209) | 1.179 (0.11) | 1.144 (0.11) | 1.126 (0.11) | 1.046 (0.14) | 1.122 (0.13) | <0.001 |

| T score (n = 209) | −0.21 (1.48) | −0.67 (1.33) | −0.63 (1.35) | −1.23 (1.53) | −0.70 (1.74) | 0.003 |

FRAX: Fracture Risk Assessment; n: total number in that cohort; BMD: bone mineral density; SD: standard deviation.

aThe cohort was divided into quartiles, based on FRAX 10-year major osteoporotic fracture risk, with quartile 1 the lowest risk and quartile 4 the highest risk. Data are mean (SD).

Eighty-eight (36%) patients were at intermediate risk of developing fragility fractures (indicative of the need for DXA scanning), while 8 (3%) patients were classified as high risk (indicating initiation of pharmacological treatment; Table 3). Eighty-one of the 88 patients in the intermediate category had consented for a DXA scan. Fourteen of these patients were defined as osteoporotic and, therefore, reclassified into the high-risk category, giving a total of 22 (9%) patients identified to be at high risk (Table 4). Only 32% and 55% of these patients were on bisphosphonates and vitamin D supplements, respectively. Fourteen (9%) patients were on bisphosphonates, despite being at low risk of developing future fractures (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of patients on maintenance steroids, bone protection and who had DXA scans within categories based on FRAX® scores.a

| On bisphosphonates, n (%) | On vitamin D, n (%) | On maintenance steroids, n (%) | Had DXA scan, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk (n = 151) | 14 (9) | 24 (16) | 16 (11) | 121 (80) |

| Intermediate risk (n = 88) | 16 (18) | 33 (38) | 11 (13) | 81 (92) |

| High risk (n = 8) | 4 (50) | 5 (63) | 1 (13) | 7 (88) |

FRAX: Fracture Risk Assessment; n: total number in that cohort; DXA: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

aThe cohort was divided into low-, intermediate- and high risk according to the FRAX score algorithm. From the intermediate-risk cohort, n represents total number in that cohort.

Table 4.

Number of patients on maintenance steroids and bone protection after reclassification of the intermediate group based on BMD.a

| On bisphosphonates, n (%) | On vitamin D, n (%) | On maintenance steroids, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk (n = 218) | 27 (12) | 45 (21) | 26 (12) |

| High risk (n = 22) | 7 (32) | 12 (55) | 1 (5) |

FRAX: Fracture Risk Assessment; n: total number in that cohort; DXA: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; BMD: bone mineral density.

aThe intermediate group was reclassified into low- and high risk according to the whole body DXA scans. Patients defined as osteoporotic (t scores of less than −2.35) were categorized as high risk, while t scores of more than −2.35 were categorized as low.

A total of 209 patients consented for DXA scanning. BMD assessment was appropriate in 81 (39%) of these patients, given that they were in the intermediate-risk category. Furthermore, 121 (58%) patients did not necessarily require BMD assessment according to NOGG recommendations, as they were at low risk.

Discussion

This is the first systematic estimation of fracture risk using a validated risk stratification algorithm (FRAX) in a cohort of patients with advanced COPD, a population known to be at high risk for osteoporosis. We show that almost 40% of the cohort were at intermediate- or high risk of developing fragility fractures, indicative of the need for either objective assessment of BMD or initiation of pharmacological therapy, according to the current guidance.8,9 Furthermore, we show that treatment is poorly targeted to those at high risk giving rise to potential over- and under-treatment.

While the FRAX algorithm has been well validated in elderly women and other populations,20 there are few studies investigating the accuracy of FRAX risk prediction in patients with COPD. Ogura-Tomomatsu et al. reported a poor correlation between the FRAX scores and the prevalence of vertebral fractures in moderate-to-severe COPD cases,21 although the small study sample and low prevalence of vertebral fractures in the study may have contributed to these findings. The FRAX calculation does not include disease-specific severity factors (such as FEV1) in the algorithm, which may reduce the reliability in the COPD population. Alternative osteoporosis risk stratification tools (e.g. QFracture [risk engine built by clinrisk - http://qfracture.org]) may be comprehensive in identifying a broad range of risk factors but are less practically applicable in routine clinical settings due to the extensive list of clinical information that is required to calculate the algorithm.8 FRAX is, therefore, a more practical option for assessing fracture risk.

We report the association of increased FRAX-estimated fracture risk with a number of disease and systemic indices. This is in line with previous cross-sectional studies that have investigated factors relating to objectively measured low BMD and vertebral fractures.22–24 For example, in keeping with our findings, Vries et al. showed that patients with symptoms relating to COPD and at least one exacerbation in the last year were at higher risk of developing further vertebral or hip fractures than those who were asymptomatic or without exacerbations.24 These associations may be mediated through shared risk factors between osteoporosis and COPD, for example, reduced physical activity, muscle strength and nutritional depletion. Similarly, frequent exacerbations are associated with higher cumulative doses of steroids that may predispose to reduced BMD and increased fracture risk.25

The asymptomatic nature of osteoporosis can make detection of the disease challenging. Previous reports have indicated a high prevalence of osteoporosis or vertebral fractures, leading to the suggestion that proactive screening for low BMD should be incorporated into disease management programmes for more severe or complex COPD.26,27 Our data show that DXA scans were appropriate in only 39% of the population, indicating that the use of a risk prediction tool such as FRAX can aid clinicians in identifying patients appropriate for BMD assessment and allow targeted use of DXA scans.

Only 3% of our population were identified to be at high risk by the FRAX scores, although we recognize that this might be an underestimate because components of the score (such as family history of fragility fractures) were not systematically recorded. In line with this, 9% of the cohort was reclassified into high risk following DXA scanning of the intermediate group. After reclassification using DXA, we found that only 55% of the high-risk group were on vitamin D supplements and less than half were on bisphosphonates, suggesting the potential for under-treatment of this group. Such under-treatment has been previously reported, though these studies targeted patients with known osteoporosis, rather than those at potential risk.12,13,28,29 Graat-Verboom et al. also reported suboptimal treatment in their COPD cohort.12 This may be due to the asymptomatic nature of osteoporosis, coupled with the lack of clear guidance regarding osteoporosis case identification and fracture risk assessment among COPD patients.12 We recognize also that some patients in this group may not be suitable for or wish to take medical therapy because they have reached a more advanced phase of their disease, where the therapeutic priority is palliation rather than primary or secondary prevention. Additionally, 9% of patients in the low-risk category were also on bisphosphonates, potentially identifying patients who may be unnecessarily exposed to the risk of side effects.

We acknowledge limitations to the conclusions that can be drawn from our findings. As alluded to the above, clinical information needed to calculate the FRAX score was not purposefully sought and if not recorded, was assumed to be absent. This may have underestimated the fracture risk within the cohort. However, this issue highlights the need for a risk stratification tool that clinicians can use to ensure COPD patients at risk of fractures are identified. We used frequency of exacerbations requiring systemic treatment as a surrogate for systemic corticosteroid use on the assumption that these would have been part of standard treatment for these events. We used whole body DXA measures of BMD rather than femoral neck DXA in conjunction with the FRAX score. Although NOGG guidance is based on the use of femoral neck measurements of bone density,9 there is evidence that whole body DXA can assist in identifying osteoporotic patients who may require treatment. Boyanov reported the threshold for osteoporosis with whole body DXA scans as t < −2.35.19 Therefore, reclassification of osteoporotic patients (according to whole body BMD) in the intermediate-risk group to high-risk group was used as an alternative approach to recalculating FRAX probability using femoral neck BMD.

The FRAX score is a validated risk stratification tool that is quick and easy to perform in the clinic. It can facilitate the identification of patients at higher risk of fragility fractures prompting clinicians to consider the need for bone protection therapy and assist patients in making informed decisions about their treatment. We propose items in the patient’s history that are markers of the risk of fragility fractures (and part of the FRAX algorithm) should be routinely elicited in hospital clinics managing advanced or complex COPD.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the patients who took part in the study and also the Department of Respiratory Medicine in Glenfield Hospital for hosting and assisting with the study. Special thanks to Nicole Toms for aiding in the implementation of study protocols and Ben James for data collection. This study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Leicester Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily of the National Health Service, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Authors’ Note: International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) grants permission for the use of FRAX® screeshots if the following text is used to describe FRAX®. FRAX® is a sophisticated risk assessment instrument, developed by the University of Sheffield. It uses risk factors in addition to DXA measurements for improved fracture risk estimation. It is a useful tool to aid clinical decision making about the use of pharmacologic therapies in patients with low bone mass. The International Osteoporosis Foundation supports the maintenance and development of FRAX®. ©International Osteoporosis Foundation, Reprinted with permission from the IOF. All rights reserved.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: Prof. Steiner reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and GSK; non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK; and personal fees from Nutricia, outside the submitted work. Dr Greening reports personal fees and non-financial support from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Divo M, Cote C, de Torres JP, et al. Comorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BODE Collaborative Group. Am J Respir Crit Med 2012; 186(2): 155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lehouck A, Boonen S, Decramer M. COPD, bone metabolism, and osteoporosis. Chest 2011; 139(3): 648–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Luise C, Brimacombe M, Pedersen L. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and mortality following hip fracture: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol 2008; 23: 115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bilezikian MD. Efficacy of bisphosphonates in reducing fracture risk in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Am J Med 2009; 122(2): S14–S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cesareo R, Lozzino M, D’onofrio L. Effectiveness and safety of calcium and vitamin D treatment for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Minerva Endocrinol 2015; 40(3): 231–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Royal College of Physicians. Osteoporosis: clinical guidelines for the prevention and treatment. London: Royal College of Physicians, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O. The use of clinical risk factors enhances the performance of BMD in the prediction of hip and osteoporotic fractures in men and women. Osteoporos Int 2007; 18: 1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Osteoporosis: assessing the risk of fragility fracture, Clinical Guidelines. NICE Guideline (CG146), 2012. London: National Clinical Guideline Centre. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Compston J, Bowring C, Cooper, et al. National Osteoporosis Guideline Group. Diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and older men in the UK. National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG) update 2013. Maturitas 2013; 75: 392–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A. FRAX® and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int 2008; 19: 385–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. WHO. Centre for Metabolic Bone disease. FRAX® Fracture Risk Assessment Tool. https://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/index.aspx. (2011, accessed 02 March 2016).

- 12. Graat-Verboom L, Spruit MA, van den Borne BE. Correlates of osteoporosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an underestimated systemic component. Respir Med 2009; 103: 1143–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Graat-Verboom L, van den Borne BE, Frank WJ. Osteoporosis in COPD outpatients based on bone mineral density and vertebral fractures. JBMR 2011; 26: 561–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Steiner MC, Evans RA, Greening NJ. Comprehensive respiratory assessment in advanced COPD: a “campus to clinic” translational framework. Thorax 2015; 70: 805–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Singh SJ, Morgan MD, Scott S. Development of a shuttle walking test of disability in patients with chronic airways obstruction. Thorax 1992; 47(12): 1019–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Edwards RH, Young A, Hosking GP. Human skeletal muscle function: description of tests and normal values. Clin Sci Mol Med 1977; 52: 283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Quanjer P, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. IERS Global Lung Function Initiative. Eur Respir J 2012; 40(6): 1324–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jones SE, Maddocks M, Kon SSC. Sarcopenia in COPD: prevalence, clinical correlates and response to pulmonary rehabilitation. Thorax 2015; 70(3): 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boyanov M. Estimation of lumbar spine bone mineral density by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry: standard anteroposterior scans vs sub-regional analyses of whole-body scans. Br J Radiol 2008; 81: 637–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bolland MJ, Siu AT, Mason BH. Evaluation of the FRAX and Garvan fracture risk calculators in older women. Bone Miner Res 2011; 26(2): 420–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ogura-Tomomatsu H, Asano K, Tomomatsu K. Predictors of osteoporosis and vertebral fractures in patients presenting with moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive lung disease. COPD 2012; 9(4): 332–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vrieze A, de Greef MHG, Wýkstra PJ. Low bone mineral density in COPD patients related to worse lung function, low weight and decreased fat-free mass. Osteoporos Int 2007; 18: 1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Majumdar SR, Villa-Roel C, Lyons KJ. Prevalence and predictors of vertebral fracture in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2010; 104(2): 260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vries F, van Staa TP, Bracke MSGM. Severity of obstructive airway disease and risk of osteoporotic fracture. Eur Respir J 2005; 25: 879–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A. A meta-analysis of prior corticosteroid use and fracture risk. J Bone Miner Res 2004; 19(6): 893–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harrison RA, Siminoski K, Vethanayagam D. Osteoporosis-related kyphosis and impairments in pulmonary function: a systematic review. J Bone Miner Res 2007; 22: 447–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nuti R, Siviero P, Maggi S. Vertebral fractures in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the EOLO Study. Osteoporos Int 2009; 20: 989–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gruntmanis U. Male osteoporosis: deadly, but ignored. Am J Med Sci 2007; 333: 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ruggiero C, Baroni M, Zengarni E. Underdiagnosis and undertreatment of nursing home residents at high risk of fragility fractures. J Nurs Home Res 2016; 2: 57–63. [Google Scholar]