Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To describe variation in empirical antibiotic selection in infants <60 days old who are hospitalized with skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTIs) and to determine associations with outcomes, including length of stay (LOS), 30-day returns (emergency department revisit or readmission), and standardized cost.

METHODS:

Using the Pediatric Health Information System, we conducted a retrospective study of infants hospitalized with SSTI from 2009 to 2014. We analyzed empirical antibiotic selection in the first 2 days of hospitalization and categorized antibiotics as those typically administered for (1) staphylococcal infection, (2) neonatal sepsis, or (3) combination therapy (staphylococcal infection and neonatal sepsis). We examined the association of antibiotic selection and outcomes using generalized linear mixed-effects models.

RESULTS:

A total of 1319 infants across 36 hospitals were included; the median age was 30 days (interquartile range [IQR]: 17–42 days). We observed substantial variation in empirical antibiotic choice, with 134 unique combinations observed before categorization. The most frequently used antibiotics included staphylococcal therapy (50.0% [IQR: 39.2–58.1]) and combination therapy (45.4% [IQR: 36.0–56.0]). Returns occurred in 9.2% of infants. Compared with administration of staphylococcal antibiotics, use of combination therapy was associated with increased LOS (adjusted rate ratio: 1.35; 95% confidence interval: 1.17–1.53) and cost (adjusted rate ratio: 1.39; 95% confidence interval: 1.21–1.58), but not with 30-day returns.

CONCLUSIONS:

Infants who are hospitalized with SSTI experience wide variation in empirical antibiotic selection. Combination therapy was associated with increased LOS and cost, with no difference in returns. Our findings reveal the need to identify treatment strategies that can be used to optimize resource use for infants with SSTI.

Within the United States, skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTIs) are responsible for nearly 60 000 pediatric admissions annually, with estimated aggregate annual charges of 840 million dollars.1 Hospitalizations for SSTI have become more frequent, with previous research revealing that infancy is independently associated with longer hospital length of stay (LOS) and increased cost.2,3 Among infants <60 days of age, clinical practice varies greatly in the evaluation of SSTIs.4,5 This variation may reflect health care provider concern for a possible increased risk of concomitant invasive bacterial infections (IBIs) because of the immaturity of the infant immune system.6 Variation in patient evaluation likely extends beyond diagnostic testing practices to include the decision of which antibiotics to empirically administer, specifically the decision to administer narrow-spectrum (ie, SSTI-directed) antibiotics or broad-spectrum antibiotics. Such variation is important to assess because broad-spectrum antibiotic use is associated with the development of antimicrobial resistance, Clostridium difficile infection, and adverse drug reactions.7 Early postnatal antibiotic use can influence the developing neonatal intestinal microbiome8–10 and may lead to lifelong consequences, including increased BMI, increased rates of diarrhea in early childhood, and an increased risk of developing allergies.11–13

In an effort to help standardize care, the Infectious Diseases Society of America published guidelines on the management of SSTIs and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections.14,15 However, these guidelines largely rely on data derived from studies of older children and adults to inform a consensus statement of antimicrobial management for SSTI. The neonatal literature used to inform these recommendations was largely based on a retrospective chart review from a single institution.16 Consequently, the extent to which these guidelines can be generalized to all infants with SSTI is unclear. Identifying patterns of antibiotic selection and the associated health outcomes across a larger, more diverse cohort of infants may help clinicians to make better empirical antibiotic choices and optimize resource use for infants with SSTI. Thus, our aims for this study are to describe empirical antibiotic selection in infants with SSTI and investigate the association of different empirical antibiotic regimens with LOS, readmission rates, and cost.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a multicenter, retrospective cohort study of infants <60 days of age with a diagnosis of SSTI. We extracted data from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), an administrative database of 45 free-standing pediatric hospitals in the United States that are affiliated with the Children’s Hospital Association (Lenexa, KS). Patient data are deidentified within PHIS; however, encryption of patient identifiers allows for tracking of individual patients across visits. The current study included data from a total of 36 hospitals, with 9 hospitals excluded for lack of emergency department (ED) data or low hospital volumes (<10 cases). This study was reviewed and approved by the local institutional review board.

Study Population

Inclusion Criteria

Infants <60 days of age hospitalized (inpatient or observation status) at a PHIS-participating site from January 1, 2009, to December 31, 2014, were eligible for inclusion. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes were used to identify infants with SSTI within the PHIS database. Infants were considered for inclusion on the basis of the presence of an ICD-9-CM principal diagnosis for an SSTI, including cellulitis, abscess, carbuncle, furuncle, or mastitis (Supplemental Table 4).2–5,17,18 If an infant had multiple hospitalizations within a 30-day period, only the first hospitalization was considered an index admission; subsequent ED revisits or hospitalizations were considered returns and were defined as same-, related-, or all-cause returns.

Exclusion Criteria

To identify infants with SSTI who were otherwise healthy, we excluded infants with primary immunodeficiency, HIV, malignancy, and complex chronic conditions.19 Infants with dacryocystitis, impetigo, pustulosis, lymphadenitis, omphalitis, perirectal abscess, fistula, and orbital cellulitis were also excluded (Supplemental Table 4) because of the potential that these infections could be managed differently and/or could require more expanded antibiotic coverage on the basis of the likely pathogen.14,20–25 Finally, infants were excluded if they did not receive systemic antibiotic therapy (oral or parenteral) within the first 2 days of hospitalization or if they received very broad-spectrum antibiotics (eg, cefepime or piperacillin and tazobactam) secondary to the possibility of coding misclassification and/or the treatment of conditions beyond SSTI or neonatal fever.

Antibiotic Classification

Empirical antibiotic selection was defined as antibiotics administered during the first 2 days of hospitalization. Because billing code data in the PHIS do not distinguish between administration in the ED or inpatient setting, our definition inherently included antibiotics given in the ED. This definition was chosen to capture the window of time when microbiologic test results are not available to guide the decision for antibiotic choice. Empirical antibiotic selection was divided into 2 broad categories: parenteral antibiotics and oral antibiotics (Supplemental Table 5). Parenteral antibiotics were further subdivided into antibiotics typically administered for staphylococcal infection, antibiotics typically administered for neonatal sepsis, and combination therapy (staphylococcal infection and neonatal sepsis). Antibiotics typically administered for staphylococcal infection included ampicillin-sulbactam, cefazolin, clindamycin, oxacillin, nafcillin, and vancomycin. Because the PHIS does not contain data on local susceptibilities, we chose to include agents with activity against methicillin-susceptible S aureus and/or methicillin-resistant S aureus with the assumption that providers would choose an agent on the basis of their local patterns of resistance. Antibiotics typically administered for neonatal sepsis included ampicillin and gentamicin, ampicillin and a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin, or a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin alone. Combination therapy was defined as concomitant use of neonatal sepsis antibiotics and staphylococcal antibiotic(s). The oral antibiotic category was defined as use of oral preparations alone during the first 2 days of hospitalization. Categorization was reviewed and confirmed by 1 of the board-certified pediatric infectious diseases physicians in the study group (R.J.M).

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures included hospital LOS (in days), returns (ED revisits and/or hospital readmission) within 30 days, and cost. The time frame of 30 days was chosen to measure subsequent visits associated with treatment failure, antibiotic-associated adverse effects, or IBI. Return visits were further classified as same cause, related cause, and/or all cause (Supplemental Table 6). A same-cause return was defined as a return for any of the diagnoses in our case identification strategy. A related-cause return was defined a priori and by group consensus as a return for reasons that could reasonably be attributed to management of an SSTI (eg, bacteremia, fever, and diarrhea). All-cause returns were defined as returns for any reason. Cost of index hospitalization included use from the ED visit and hospitalization. Costs are presented as standardized costs by using methodology previously described by Keren et al.26

Demographics and Covariates

Demographic characteristics included age, sex, race and/or ethnicity, primary payer, and region of the United States. All records were assessed for billing codes for fever,27 site of infection, IBI, incision and drainage procedures, obtainment of cultures (blood, cerebrospinal fluid [CSF], and wound), ICU services, and peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) placement. IBI was defined as bacteremia and/or sepsis, meningitis, osteomyelitis, and pyogenic arthritis and was identified through ICD-9-CM codes (Supplemental Table 4). Additionally, we examined case mix index (CMI), which is a relative weight assigned to each discharge on the basis of All-Patient Refined Diagnosis Group (APR-DRG) assignment and ARP-DRG severity of illness. The weights are derived by Truven Health Analytics (Ann Arbor, MI) as the ratio of the average charge for discharges within a specific APR-DRG and severity of illness combination to the average charge for all discharges in the database. For simplicity of reporting, we split the weights at the median and combined the middle 2 quartiles into a single group to produce 3 categories: minor, moderate and/or major, and extreme.

Validation

An internal validation study was performed through chart review at 2 PHIS hospitals to assess the accuracy of our case identification strategy. Of the 131 medical records reviewed, our case identification strategy was associated with a positive predictive value of 90.8% (N = 119) for identifying included SSTI diagnoses. Two infants (1.5%) with billing codes for cellulitis had documentation to support a diagnosis of neonatal fever, and 10 infants (7.6%) with billing codes for cellulitis had documentation to support a diagnosis of perirectal abscess. Of the 131 charts reviewed, fever (temperature ≥38°C reported or documented) was identified for 18 infants (13.7%). However, fever was coded for only 9 infants (6.9%) in the PHIS. On chart review of these 9 infants, 4 had a documented fever at ≥38°C, 1 had a temperature of 37.9°C, 1 had a subjective fever reported, and 3 infants did not have documentation to support fever. On chart review, 6 infants (4.6%) had positive results on blood cultures, all of which were considered to be contaminants by the medical team (4 coagulase-negative staphylococci, 1 Streptococcus parasanguinis, and 1 Bacillus species [not anthracis]). No cases of meningitis, osteomyelitis, or pyogenic arthritis were identified.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated summary statistics for continuous variables with medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), and categorical variables were summarized with frequencies and percentages. We made comparisons between infants who did and did not have a return using the χ2 test for categorical measures or the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous measures. We examined the association between antibiotic groups (eg, staphylococcal and combination therapy) and outcomes using generalized linear mixed-effects models with a random intercept for each hospital. We performed age-stratified, diagnosis-stratified, and overall analyses. For diagnosis-stratified analyses, adjustments were made for age, sex, hospital, census region, CMI, incision and drainage, fever code, culture obtainment (blood, CSF, and wound), and ICU use. For age-stratified and overall analyses, we additionally adjusted for infection type. For the outcomes of LOS and cost, we used an exponential distribution, and we present the results as rate ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For all other outcomes, we used a binomial distribution, and we present the results as odds ratios with 95% CIs. Finally, we performed a sensitivity analysis, removing children with CSF cultures to isolate infants who did not have a complete evaluation for serious bacterial infection on the basis of their initial presentation. All statistical analyses were performed by using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC), and P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

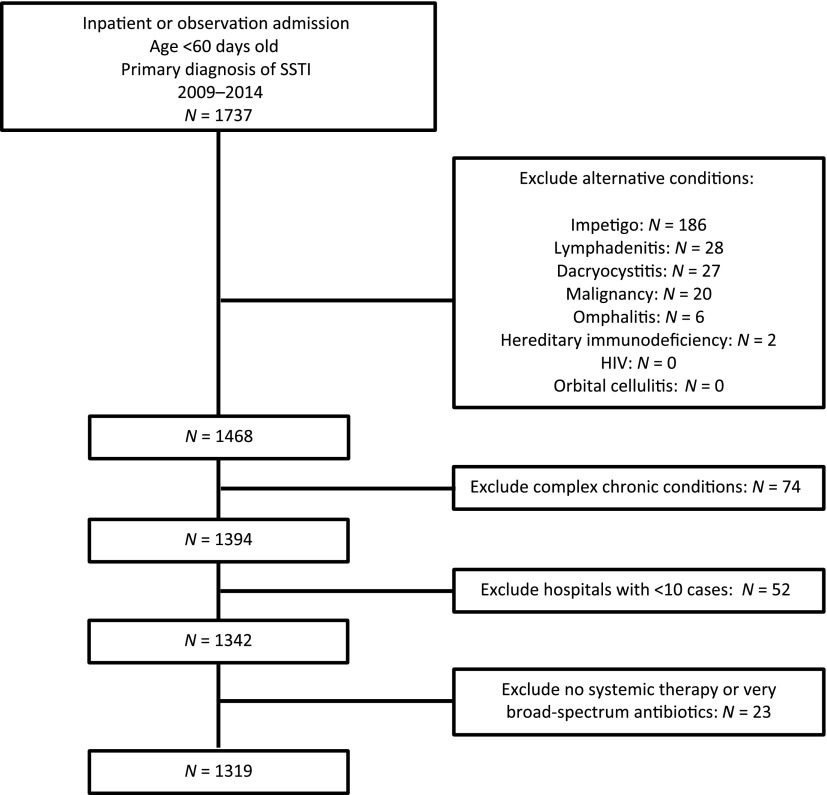

Within the study period, 1319 infants met inclusion criteria (Fig 1). The median age of infants was 30 days (IQR: 17–42 days). The majority of infants were non-Hispanic white, had government insurance, and were located in the southern United States (Table 1). A total of 790 (59.9%) infants were hospitalized with a diagnosis code for cellulitis and abscess, 4 (0.3%) for carbuncle and furuncle, and 525 (39.8%) for mastitis. Incision and drainage were documented in 234 (17.7%) infants. Overall, 1063 (80.6%) infants had a blood culture obtained alone or in combination with a CSF culture, 408 (30.9%) had a CSF culture obtained, and 834 (63.2%) had a wound culture obtained. A fever code was documented for 59 (4.5%) infants, and an IBI was coded for 24 (1.8%) infants. We observed increased obtainment of CSF cultures among infants who received neonatal (60.0%) or combination therapy (49.0%) compared with infants who received staphylococcal (11.7%) or oral antibiotics (0%; Supplemental Table 7). Additionally, we observed increased use of neonatal or combination therapy among infants 0 to 28 days and among infants with a documented fever code.

FIGURE 1.

Cohort flow diagram.

TABLE 1.

Cohort Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Overalla | No Returna | Same- or Related-Cause Returna | Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1319 | 1248 | 71 | .930 |

| Age, n (%) | ||||

| 0–28 d | 625 (47.4) | 591 (47.4) | 34 (47.9) | |

| 29–60 d | 694 (52.6) | 657 (52.6) | 37 (52.1) | |

| Boys, n (%) | 677 (51.3) | 632 (50.6) | 45 (63.4) | .037 |

| Race and/or ethnicity, n (%) | .208 | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 593 (45.0) | 560 (44.9) | 33 (46.5) | |

| Non-Hispanic black or African American | 341 (25.9) | 325 (26.0) | 16 (22.5) | |

| Hispanic | 234 (17.7) | 216 (17.3) | 18 (25.4) | |

| Asian American | 44 (3.3) | 44 (3.5) | — | |

| Other | 107 (8.1) | 103 (8.3) | 4 (5.6) | |

| Payer, n (%) | .161 | |||

| Government | 787 (59.7) | 737 (59.1) | 50 (70.4) | |

| Private | 489 (37.1) | 470 (37.7) | 19 (26.8) | |

| Other | 43 (3.3) | 41 (3.3) | 2 (2.8) | |

| Region,c n (%) | .020 | |||

| Midwest | 279 (21.2) | 264 (21.2) | 15 (21.1) | |

| Northeast | 162 (12.3) | 145 (11.6) | 17 (23.9) | |

| South | 630 (47.8) | 602 (48.2) | 28 (39.4) | |

| West | 248 (18.8) | 237 (19.0) | 11 (15.5) | |

| Type of infection, n (%) | .819 | |||

| Cellulitis and abscess | 790 (59.9) | 749 (60.0) | 41 (57.8) | |

| Carbuncle and furuncle | 4 (0.3) | 4 (0.3) | — | |

| Mastitis | 525 (39.8) | 495 (39.7) | 30 (42.3) | |

| Site of infection, n (%) | .003 | |||

| Head | 148 (11.2) | 147 (11.8) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Neck | 55 (4.2) | 54 (4.3) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Extremity | 92 (7.0) | 87 (7.0) | 5 (7.0) | |

| Digit | 114 (8.6) | 109 (8.7) | 5 (7.0) | |

| Chest | 525 (39.8) | 495 (39.7) | 30 (42.3) | |

| Trunk | 212 (16.1) | 202 (16.2) | 10 (14.1) | |

| Buttock | 116 (8.8) | 101 (8.1) | 15 (21.1) | |

| Unspecified | 57 (4.3) | 53 (4.3) | 4 (5.6) | |

| Antibiotics,d n (%) | .473 | |||

| Staphylococcal | 635 (48.1) | 603 (48.3) | 32 (45.1) | |

| Neonatal sepsis | 55 (4.2) | 50 (4.0) | 5 (7.0) | |

| Combination therapy | 614 (46.6) | 580 (46.5) | 34 (47.9) | |

| Oral | 15 (1.1) | 15 (1.2) | — | |

| Blood or CSF culturee | .612 | |||

| Blood culture alone | 724 (54.9) | 681 (54.6) | 43 (60.6) | |

| CSF culture alone | 408 (30.9) | 389 (31.2) | 19 (26.8) | |

| Neither blood nor CSF culture | 187 (14.2) | 178 (14.3) | 9 (12.7) | |

| CMI, n (%) | .743 | |||

| Minor | 988 (74.9) | 935 (74.9) | 53 (74.7) | |

| Moderate | 272 (20.6) | 256 (20.5) | 16 (22.5) | |

| Major | 59 (4.5) | 57 (4.6) | 2 (28) | |

| Fever, n (%) | 59 (4.5) | 56 (4.5) | 3 (4.2) | .917 |

| Incision and drainage, n (%) | 234 (17.7) | 216 (17.3) | 18 (25.4) | .084 |

| Wound culture,e n (%) | 834 (63.2) | 787 (63.1) | 47 (66.2) | .594 |

| PICC, n (%) | 40 (3.0) | 37 (3.0) | 3 (4.2) | .547 |

| ICU, n (%) | 15 (1.1) | 15 (1.2) | — | .353 |

| LOS, d, geometric mean (95% CI) | 2.2 (2.2–2.3) | 2.2 (2.2–2.3) | 2.1 (1.8–2.4) | .352 |

| Standardized cost of index hospitalization, $, geometric mean (95% CI) | 4479 (4326–4637) | 4503 (4347–4666) | 4068 (3421–4837) | .327 |

Demographic and clinical characteristics are stratified on the basis of outcome (no return versus same- or related-cause return).

P values were calculated by using χ2 or Kruskal-Wallis tests.

Region refers to the region of the United States where the admission occurred.

Antibiotic selection was analyzed in 2 broad categories: parenteral and oral. The parenteral antibiotic category was further subdivided into antibiotics typically prescribed for staphylococcal infection, neonatal sepsis, or combination therapy (staphylococcal infection and neonatal sepsis).

Culture results were assessed on the basis of billing data. Blood culture alone includes any infant who had a blood culture but not a CSF culture. CSF culture alone includes any infant who had a CSF culture. Neither blood nor CSF culture includes infants who did not have either blood or CSF cultures obtained. Wound culture includes any infant with an aerobic, anaerobic, or bacterial culture obtained.

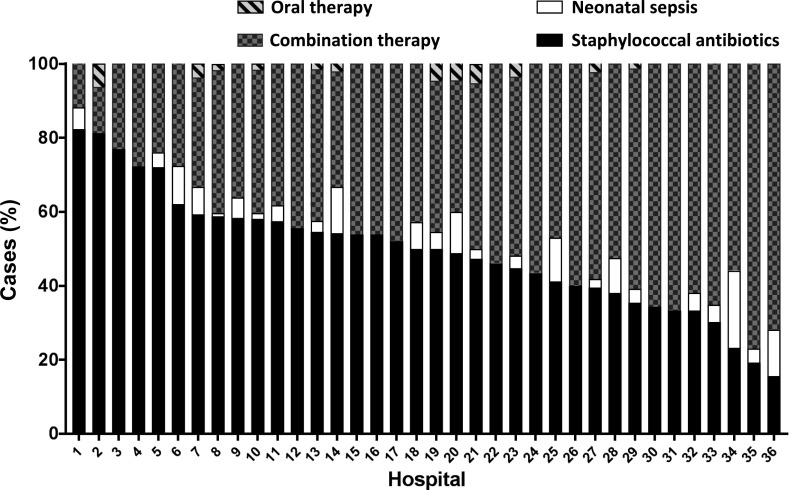

Variation in Empirical Antibiotic Selection

We observed wide variation in empirical antibiotic choice across hospitals (Fig 2). Before categorization, there were 134 unique combinations of antibiotics used in the first 2 days of hospitalization. The most frequently used antibiotic regimens included staphylococcal antibiotics (50.0% [IQR: 39.2–58.1]) and combination therapy (45.4% [IQR: 36.0–56.0]). Clindamycin was the most commonly used staphylococcal antibiotic (1057 infants; 80.1% of the entire cohort). Among all infants included in our cohort, 282 (21.4%) received vancomycin.

FIGURE 2.

Stacked bar chart of antibiotic selection across 36 children’s hospitals.

Association of Antibiotic Selection and Outcomes

In unadjusted analyses, there were significant differences in LOS (2.7 vs 1.9 days; P < .001) and standardized cost of the index encounter ($5518 vs $3726; P < .001) among infants who received combination therapy versus infants who received staphylococcal antibiotics (Table 2). After adjustment, infants who received combination therapy had an average LOS that was 35% longer than that of infants who received staphylococcal antibiotics (adjusted rate ratio [aRR]: 1.35 [95% CI: 1.17–1.53]; P < .001). Standardized costs of the index encounter were nearly 40% higher among infants who received combination therapy versus infants who received staphylococcal antibiotics (aRR: 1.39 [95% CI: 1.21–1.58]; P < .001). These findings remained similar in age-stratified, diagnosis-stratified, and sensitivity analyses (Tables 2 and 3, Supplemental Table 8). In particular, in sensitivity analyses in which infants with CSF cultures were excluded, infants who received combination therapy had an average LOS that was 37% greater and standardized costs that were 47% higher than those of infants who received staphylococcal antibiotics.

TABLE 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Outcomes are Presented and Include LOS, Standardized Cost of Index Hospitalization, and 30-d Returns

| Unadjusted Outcomesa | Adjusted Outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Antibioticc | Combination Therapy | Staphylococcal Antibiotics | Combination Versus Staphylococcal Therapy | |||

| Overall, aRR or aOR (95% CI) | 0–28 d Old, aRR or aOR (95% CI) | 29–60 d Old, aRR or aOR (95% CI) | ||||

| LOSb,c | 2.2 (2.2–2.3) | 2.7 (2.6–2.8) | 1.9 (1.8–2.0) | 1.35 (1.17–1.53) | 1.33 (1.06–1.60) | 1.31 (1.06–1.57) |

| Standardized cost of index hospitalizationb,c | $4479 ($4326–$4637) | $5518 ($5255–$5795) | $3726 ($3560–$3899) | 1.39 (1.21–1.58) | 1.37 (1.10–1.65) | 1.36 (1.10–1.61) |

| Any return | ||||||

| All cause | 122 (9.2) | 58 (9.5) | 54 (8.5) | 1.21 (0.75–2.0) | 0.87 (0.42–2.0) | 1.36 (0.67–3.0) |

| Related cause | 37 (2.8) | 20 (3.3) | 15 (2.4) | 1.28 (0.56–3.0) | 0.38 (0.11–1.0) | 2.67 (0.75–10.0) |

| Same cause | 34 (2.6) | 14 (2.3) | 17 (2.7) | 1.48 (0.62–4.0) | 1.86 (0.47–7.0) | 0.90 (0.20–4.0) |

| Readmission | ||||||

| All cause | 47 (3.6) | 22 (3.6) | 22 (3.5) | 1.56 (0.75–3.0) | 1.30 (0.44–4.0) | 1.51 (0.47–5.0) |

| Related cause | 8 (0.6) | 4 (0.7) | 4 (0.6) | 1.49 (0.25–9.0) | Non-estimable | 8.74 (0.14–532.0) |

| Same cause | 23 (1.7) | 11 (1.8) | 11 (1.7) | 1.91 (0.68–5.0) | 2.54 (0.54–12.0) | 1.23 (0.19–8.0) |

| ED revisit | ||||||

| All cause | 85 (6.4) | 41 (6.7) | 36 (5.7) | 1.01 (0.57–2.0) | 0.53 (0.22–1.0) | 1.43 (0.64–3.0) |

| Related cause | 33 (2.5) | 19 (3.1) | 12 (1.9) | 1.19 (0.49–3.0) | 0.45 (0.13–2.0) | 2.83 (0.67–12.0) |

| Same cause | 11 (0.8) | 3 (0.5) | 6 (0.9) | 0.80 (0.16–4.0) | 1.06 (0.03–35.0) | 0.59 (0.05–7.0) |

Unadjusted outcomes are presented on the basis of exposure to any antibiotic, combination therapy, or staphylococcal antibiotics. Adjusted outcomes are presented as overall and age-stratified comparisons of combination versus staphylococcal therapy, with models adjusted for age, sex, hospital, census region, CMI, infection type, incision and drainage, fever code, culture obtainment (blood, CSF, and wound), and ICU use. aOR, adjusted odds ratio.

Unadjusted LOS and cost are reported as geometric mean (95% CI). Unadjusted returns are presented as n (%) in which N = 1319 for any antibiotic, N = 614 for combination therapy, and N = 635 for staphylococcal antibiotics.

Comparisons of unadjusted LOS and cost between combination therapy and staphylococcal antibiotics groups were significant (all: P < .05).

Comparisons of adjusted LOS and cost were significant (all: P < .05).

TABLE 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Outcomes (LOS, Standardized Cost of Index Hospitalization, and 30-d Returns) Stratified by Diagnosis

| Cellulitis and Abscess | Mastitis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combination Therapya,b | Staphylococcal Antibioticsa,b | Combination Versus Staphylococcal Therapy, aRR or aOR (95% CI)c | Combination Therapya,b | Staphylococcal Antibioticsa,b | Combination Versus Staphylococcal Therapy, aRR or aOR (95% CI)c | |

| LOS | 2.7 (2.5–2.8) | 1.8 (1.7–1.9) | 1.41 (1.17–1.66) | 2.7 (2.5–2.9) | 2.0 (1.9–2.2) | 1.28 (0.99–1.57) |

| Standardized cost of index hospitalization | $5483 ($5119–$5872) | $3657 ($3456–$3871) | 1.44 (1.19–1.69) | $5583 ($5205–$5988) | $3846 ($3562–$4152) | 1.32 (1.02–1.62) |

| Any return | ||||||

| All cause | 26 (7.7) | 32 (8.2) | 1.07 (0.55–2.0) | 22 (9.0) | 32 (11.8) | 1.32 (0.61–3.0) |

| Related cause | 10 (2.9) | 8 (2.1) | 1.87 (0.62–6.0) | 6 (2.5) | 9 (3.3) | 0.61 (0.16–2.0) |

| Same cause | 5 (1.5) | 13 (3.3) | 0.75 (0.19–3.0) | 5 (2.0) | 10 (3.7) | 4.10 (0.73–23.0) |

| Readmission | ||||||

| All cause | 9 (2.7) | 16 (4.1) | 1.08 (0.39–3.0) | 6 (2.5) | 13 (4.8) | 2.89 (0.75–11.0) |

| Related cause | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 3.17 (0.22–45.0) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | 0.54 (0.02–12.0) |

| Same cause | 4 (1.2) | 8 (2.1) | 1.06 (0.22–5.0) | 4 (1.6) | 7 (2.6) | 4.39 (0.53–36.0) |

| ED revisit | ||||||

| All cause | 20 (5.9) | 19 (4.9) | 1.18 (0.53–3.0) | 17 (7.0) | 21 (7.7) | 0.76 (0.32–2.0) |

| Related cause | 10 (2.9) | 6 (1.5) | 1.80 (0.55–6.0) | 6 (2.5) | 8 (2.9) | 0.43 (0.10–2.0) |

| Same cause | 1 (0.3) | 5 (1.3) | 0.22 (0.01–5.0) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.1) | 3.17 (0.13–77.0) |

Unadjusted outcomes are presented on the basis of exposure to combination therapy or staphylococcal antibiotics. Adjusted outcomes are presented as a comparison of combination versus staphylococcal therapy, with models adjusted for age, sex, hospital, census region, CMI, incision and drainage, fever code, culture obtainment (blood, CSF, and wound), and ICU use. aOR, adjusted odds ratio.

Unadjusted LOS and cost are reported as geometric mean (95% CI). Unadjusted returns are presented as n (%) in which N = 614 for combination therapy, and N = 635 for staphylococcal antibiotics.

Comparisons of unadjusted LOS and cost between combination therapy and staphylococcal antibiotics groups were significant (all: P < .05).

Comparisons of adjusted LOS and cost were significant (all: P < .05).

Before adjustment, 30-day related-cause returns were observed in 2.8% (95% CI: 2.0–3.8) of infants, whereas same-cause returns were observed in 2.6% (95% CI: 1.8–3.6) of infants (Table 2). In both unadjusted and adjusted analyses, there were no significant differences in all-, related-, or same-cause return rates among infants who received combination therapy versus infants who received staphylococcal antibiotics. Similarly, no significant differences were observed in age-stratified or diagnosis-stratified analyses (Tables 2 and 3).

Discussion

In this multicenter study, we observed considerable variation in the choice of the empirical antibiotic selected to manage SSTI in infants <60 days old who were hospitalized. Despite wide variation in antibiotics, the vast majority of infants received an antibiotic within 1 of 2 broad categories (staphylococcal antibiotics or combination therapy). Those infants who received combination therapy had a longer LOS and higher costs compared with those who received staphylococcal antibiotics. Despite observing longer LOS among infants who received combination therapy versus staphylococcal coverage, we did not observe lower rates of 30-day returns (ED revisits and/or readmission). With our findings, we suggest that there may be opportunities to reduce broad-spectrum antibiotic use in infants with SSTI without adversely affecting clinical outcomes.

With our current study, we build on previous single- and regional-center investigations by demonstrating significant variation in empirical antibiotic selection for infants with SSTI within and across geographically diverse institutions. Variation in empirical antibiotic exposure is important to recognize, considering the large proportion of infants who received potentially unnecessary broad-spectrum coverage in our study and the growing body of research in which possible negative consequences from early postnatal broad-spectrum antibiotic exposure are suggested.8–13 Consistent with previous research of young infants with SSTI,4,5,28 the prevalence of IBI in our study was 1.8%; as such, with our findings, we suggest that for a majority of infants with SSTI, there may be an opportunity to safely reduce broad-spectrum antimicrobial use. However, future research is needed to develop risk stratification tools to determine which infants are at a higher risk for the development of IBI, allowing for a more targeted approach to invasive testing and broad-spectrum antimicrobial use.

Oral agents were rarely used as empirical therapy among our cohort of infants who were hospitalized. This finding may partly reflect the lack of strong evidence for empirical oral therapy in infants, concern for antibiotic absorption and relative lack of pharmacokinetic data for the youngest patients, the perceived severity of infection, clinician concern for IBI, failure of outpatient treatment, or physician perception of the need for parenteral therapy for patients who are hospitalized. Additionally, although the vast majority of SSTI infections occur secondary to staphylococcal or streptococcal organisms,14 a total of 51% of infants within our study group were exposed to broad-spectrum antibiotics, which provide enhanced Gram-negative coverage but no added benefit for treatment of the most commonly identified organisms responsible for SSTI (Gram-positive organisms). Although some of the infants who received broad-spectrum antibiotics may have been febrile or appeared ill, our observation of longer LOS and higher costs among infants receiving combination therapy persisted even after controlling for fever, CMI, or obtainment of a CSF culture. Taken together, our findings reveal the need to evaluate the efficacy and safety of oral and narrow-spectrum antibiotic therapy for treatment of SSTI in young infants.

Infants who received combination therapy in our current study were younger and more frequently had codes for fever and CSF testing. Infants receiving combination therapy had LOSs and costs that were 35% to 40% higher than those of infants who received staphylococcal coverage alone. Our findings may in part reflect physician decision to delay discharge while awaiting culture results and may further reveal the need for diagnostic testing and antimicrobial stewardship interventions that balance the benefits of broadly evaluating and treating the few infants with concomitant IBI with the risks of performing potentially unnecessary tests and treating many infants with unnecessarily broad antibiotic therapy.29 Future efforts to address potential reductions of LOS in this population will be important because hospitalization can be associated with the risk of acquiring nosocomial infections, increased psychosocial burden on families, and reduced quality of life for the child who is hospitalized.30–33

There are limitations to our study. First, we used an administrative database to obtain our data; consequently, some of the variation we observed may reflect differences in administrative billing and coding practices. For example, fever was not reliably coded in our study, and compared with other similar investigations, assignment of ICD-9-CM codes for fever was low.5 Lack of reliable fever coding limits our ability to examine the impact of fever on antibiotic prescribing and limits our ability to make any recommendations regarding the appropriate treatment of SSTI in the setting of fever. The use of an administrative data set also limits our ability to evaluate the association of patient presentation with clinical decision-making. For example, lack of codes for CSF testing does not exclude the possibility that a lumbar puncture was indicated but unsuccessful or not attempted. We had a limited ability to assess the severity of SSTI (including bedside drainage procedures) and local patterns of resistance or to examine microbiologic data, which are factors that might have influenced empirical antimicrobial selection. However, our focus on empirical antibiotic therapy would be expected to minimize the influence of microbiologic test results on antibiotic choices. Finally, because our study population was composed solely of infants who were hospitalized at children’s hospitals, our results may not be generalizable to infants in other settings.

Conclusions

Infants hospitalized with SSTI experience wide variation in empirical antimicrobial selection. Compared with staphylococcal antibiotics alone, use of combined therapy was associated with increased LOS and cost (without increased rates of ED revisits and/or readmissions). Given the low rate of IBI in infants with SSTI, we suggest with our findings that there may be an opportunity to safely reduce broad-spectrum antimicrobial use in infants with SSTI.

Footnotes

Dr McCulloh’s current affiliation is Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, Omaha, NE.

Dr Markham conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the initial manuscript; Dr Hall was involved in the study design, supervised the data analysis and interpretation, and reviewed and revised the manuscript as submitted; Drs Queen, Aronson, Wallace, Foradori, Hester, Nead, Lopez, and Cruz assisted with the study design, participated in the interpretation of data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr McCulloh supervised the conceptualization and design of the study, participated in the interpretation of data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported, in part, by Clinical and Translational Science Awards grant KL2 TR001862 (to Dr Aronson) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science and by National Institute for Child Health and Human Development grant UG1 OD024943 02 (to Dr McCulloh), both components of the National Institutes of Health. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of National Institutes of Health. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUPnet. Available at: https://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/#setup. Accessed November 15, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Lopez MA, Cruz AT, Kowalkowski MA, Raphael JL. Trends in resource utilization for hospitalized children with skin and soft tissue infections. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/131/3/e718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez MA, Cruz AT, Kowalkowski MA, Raphael JL. Factors associated with high resource utilization in pediatric skin and soft tissue infection hospitalizations. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(4):348–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kharazmi SA, Hirsh DA, Simon HK, Jain S. Management of afebrile neonates with skin and soft tissue infections in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(10):1013–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hester G, Hersh AL, Mundorff M, et al. Outcomes after skin and soft tissue infection in infants 90 days old or younger. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(11):580–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson CB. Immunologic basis for increased susceptibility of the neonate to infection. J Pediatr. 1986;108(1):1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shehab N, Lovegrove MC, Geller AI, Rose KO, Weidle NJ, Budnitz DS. US emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events, 2013-2014. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2115–2125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka S, Kobayashi T, Songjinda P, et al. Influence of antibiotic exposure in the early postnatal period on the development of intestinal microbiota. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2009;56(1):80–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson MK, Crofts TS, Dantas G. Antibiotics and the developing infant gut microbiota and resistome. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;27:51–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker A. Intestinal colonization and programming of the intestinal immune response. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(suppl 1):S8–S11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prince BT, Mandel MJ, Nadeau K, Singh AM. Gut microbiome and the development of food allergy and allergic disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015;62(6):1479–1492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenwood C, Morrow AL, Lagomarcino AJ, et al. Early empiric antibiotic use in preterm infants is associated with lower bacterial diversity and higher relative abundance of Enterobacter. J Pediatr. 2014;165(1):23–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saari A, Virta LJ, Sankilampi U, Dunkel L, Saxen H. Antibiotic exposure in infancy and risk of being overweight in the first 24 months of life. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):617–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):147–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. ; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children [published correction appears in Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(3):319]. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(3):e18–e55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fortunov RM, Hulten KG, Hammerman WA, Mason EO, Jr, Kaplan SL. Evaluation and treatment of community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infections in term and late-preterm previously healthy neonates. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):937–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams DJ, Cooper WO, Kaltenbach LA, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antibiotic treatment strategies for pediatric skin and soft-tissue infections. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/128/3/e479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elliott DJ, Zaoutis TE, Troxel AB, Loh A, Keren R. Empiric antimicrobial therapy for pediatric skin and soft-tissue infections in the era of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/123/6/e959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hauser A, Fogarasi S. Periorbital and orbital cellulitis. Pediatr Rev. 2010;31(6):242–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wald ER. Periorbital and orbital infections. Pediatr Rev. 2004;25(9):312–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters TR, Edwards KM. Cervical lymphadenopathy and adenitis. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21(12):399–405 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mason WH, Andrews R, Ross LA, Wright HT., Jr Omphalitis in the newborn infant. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;8(8):521–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sawardekar KP. Changing spectrum of neonatal omphalitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23(1):22–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosen NG, Gibbs DL, Soffer SZ, Hong A, Sher M, Peña A. The nonoperative management of fistula-in-ano. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35(6):938–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keren R, Luan X, Localio R, et al. ; Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network. Prioritization of comparative effectiveness research topics in hospital pediatrics. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1155–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aronson PL, Thurm C, Alpern ER, et al. ; Febrile Young Infant Research Collaborative. Variation in care of the febrile young infant <90 days in US pediatric emergency departments [published correction appears in Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):775]. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):667–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vidwan G, Geis GL. Evaluation, management, and outcome of focal bacterial infections (FBIs) in nontoxic infants under two months of age. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(2):76–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Messacar K, Parker SK, Todd JK, Dominguez SR. Implementation of rapid molecular infectious disease diagnostics: the role of diagnostic and antimicrobial stewardship. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55(3):715–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Commodari E. Children staying in hospital: a research on psychological stress of caregivers. Ital J Pediatr. 2010;36:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rennick JE, Dougherty G, Chambers C, et al. Children’s psychological and behavioral responses following pediatric intensive care unit hospitalization: the caring intensively study. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Jawahri AR, Traeger LN, Kuzmuk K, et al. Quality of life and mood of patients and family caregivers during hospitalization for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2015;121(6):951–959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coyne I. Children’s experiences of hospitalization. J Child Health Care. 2006;10(4):326–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]