Abstract

Our goal in developing the MultiWaver software series was to be able to infer population admixture history under various complex scenarios. The earlier version of MultiWaver considered only discrete admixture models. Here, we report a newly developed version, MultiWaver 2.0, that implements a more flexible framework and is capable of inferring multiple-wave admixture histories under both discrete and continuous admixture models. MultiWaver 2.0 can automatically select an optimal admixture model based on the length distribution of ancestral tracks of chromosomes, and the program can estimate the corresponding parameters under the selected model. Specifically, for discrete admixture models, we used a likelihood ratio test (LRT) to determine the optimal discrete model and an expectation–maximization algorithm to estimate the parameters. In addition, according to the principles of the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), we compared the optimal discrete model with several continuous admixture models. In MultiWaver 2.0, we also applied a bootstrapping technique to provide levels of support for the chosen model and the confidence interval (CI) of the estimations of admixture time. Simulation studies validated the reliability and effectiveness of our method. Finally, the program performed well when applied to real datasets of typical admixed populations, such as African Americans, Uyghurs, and Hazaras.

Subject terms: Population genetics, Computational biology and bioinformatics, Evolutionary biology

Introduction

Admixture history inference is a fundamental problem for studies on admixed populations [1]. Several methods have been developed to analyze the problem based on various kinds of population admixture information, such as break points of recombination [2], admixture linkage disequilibrium [3–6], and ancestral tracks [7–12]. The length distribution of ancestral tracts provides direct information concerning the decay of the ancestral segment length, which is closely related to the admixture history. Therefore, many methods have been developed based on this type of information [7–11, 13, 14]. The history of several classical admixed populations (African Americans, Mexicans, and Uyghur) have been well studied using these methods [15–21]. However, there are two shortcomings involved in these methods. First, before estimating the parameters of admixture history, a prior admixture model was required. Second, the prior admixture model was often an overly simplified scenario, such as a hybrid-isolation (HI), gradual admixture (GA), or continuous gene flow (CGF) models. Knowledge of admixture history is often lacking when real data are analyzed, especially for complex admixed populations [2, 15, 22–24]. Therefore, results can be unreliable in cases where the selected prior model deviates from the real admixture history.

In our previous work [13], we proposed some principles of parameter estimation and model selection under a general model, but our previous method could handle only three typical two-way admixture models. To solve this problem, we developed the MultiWaver program [25], which could select the optimal admixture model and estimate the corresponding parameters under a general discrete model. Our method could deal with complex admixture scenarios involving multiple ancestral populations with multiple admixture events. In principle, our model could also be used to analyze a population with continuous admixture, since the model can deal with admixture events at any generation. However, if the true admixture model is continuous, the number of parameters could be very large (each wave has two parameters, one admixture time and one admixture proportion); consequently, the model could become very complex. In MultiWaver, we applied a likelihood ratio test (LRT) to select the best-fit model. Using this method, more parameters means greater penalties. Thus, the method tends to select an optimal multiple-wave (discrete) model rather than a continuous model, and the continuous model is often neglected.

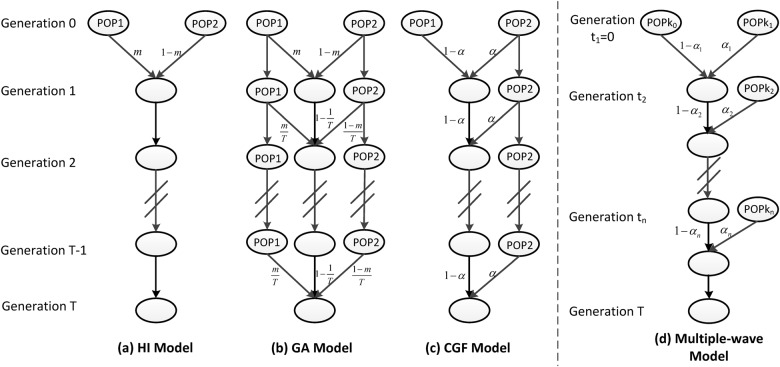

In this work, we extend the MultiWaver software to MultiWaver 2.0, which can handle both discrete and continuous models. In the new method, we consider four different models (the HI, GA, CGF, and multiple-wave models) (Fig. 1). Our new method can automatically select the optimal model among those candidate models, and the confidence interval (CI) of admixture time and supporting rate for each candidate model can be obtained via a bootstrapping procedure. We conducted simulation studies to demonstrate the effectiveness of our method. Finally, we applied our method to African Americans from the HapMap project phase III dataset [26] and to Uyghurs and Hazaras from the Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP) dataset [27].

Fig. 1.

Four different types of admixture model. a Hybrid isolation (HI) model; b Gradual admixture (GA) model; c Continuous gene flow (CGF) model. POP1: the reference population 1; POP2: the reference population 2; m is the proportion of population 1 and α = 1 − m1/T. d The multiple-wave model, where POPki is the ancestral population of the ith admixture, αi is the admixture proportion of the ith admixture, and ti is the admixture time of the ith admixture

Materials and methods

Model selection and parameter estimation

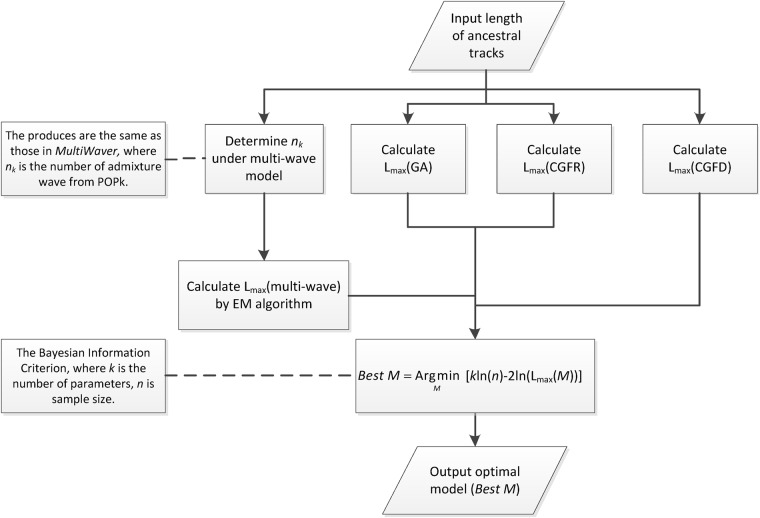

In order to infer the admixture history, we need to select an optimal model from the four different models listed above. For discrete admixture models (the HI model and multiple-wave models), we apply the LRT method to select the optimal discrete model. The results are the same as those obtained using the MultiWaver software [25]. Next, we compare the optimal discrete model with continuous admixture models (GA and CGF). However, when we include the GA and CGF models in the analysis, we find that any pairs of GA, CGF, and discrete model are all not nested, which means that no model is a special case of another. The LRT method is unavailable in this case. Therefore, we apply another method, Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) [28, 29], to select the optimal model. The value of the BIC can be calculated by the formula:

where k is the number of parameters, n is the sample size, and Lmax is the maximized value of the likelihood function. Details of the model selection procedure are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of the algorithm for model selection. Lmax (GA), Lmax (CGFR), Lmax (CGFD), and Lmax (multi-wave) are the maximized values of the likelihood function under GA, CGFR, CGFD, and multiple-wave models, respectively. Best M is the optimal model, where M is the set of GA, CGFR, CGFD, and multiple-wave models

Whether one uses the LRT or BIC method, it is necessary to calculate Lmax and to estimate the parameters of the admixture models. In our previous study [13], we employed the length distributions of ancestral tracks under the HI, GA, and CGF models. These models involve only two parameters, the admixture proportion m and the admixture time T (Fig. 1a−c). Thus, we can easily calculate Lmax and the estimates of m and T via a binary search algorithm. For multiple-wave models, the length distribution of the ancestral tracks can be written as a mixed exponential distribution [25]. We can then use the expectation–maximization algorithm [30] to calculate Lmax and to estimate the admixture time (ti) and proportion (αi) (Fig. 1d); this produces the same estimates as the MultiWaver method [25]. After obtaining Lmax for the four models, we then select an optimal model via the LRT and BIC methods. The optimal model and the corresponding estimators of admixture time and proportion can then be used to describe the inferred admixture history. The details concerning the LRT are described in Supplementary Text 1.

Bootstrapping procedures

To assess the uncertainty in optimal model selection and estimated parameter values, we also apply the bootstrapping technique in MultiWaver 2.0 to obtain a degree of support for the chosen model and the CI of the admixture time. We conduct the bootstrapping by resampling the same number of segments with replacement and use these resampled segments to infer the admixture model and its corresponding admixture time. Details of the bootstrapping procedure are described in Supplementary Text 1. MultiWaver 2.0 can be downloaded at http://www.picb.ac.cn/PGG/resource.php.

Simulation studies

We conducted simulations to evaluate the performance of MultiWaver 2.0. The simulation data were generated by the forward-time simulator AdmixSim [31]. AdmixSim can be downloaded at http://www.picb.ac.cn/PGG/resource.php. The population size of the admixed population was arbitrarily set to 5000 and remained constant in our simulations, and the length of the simulated chromosome was 3.0 Morgans, which approximates the length of chromosome 1 of the human genome. At the end of the simulation, 100 “individuals” (pairs of chromosomes) were sampled, and the ancestral tracks were recorded.

For the symmetric admixture models (HI and GA) (Fig. 1a, b), the proportions of admixture varied from 20 to 50% in steps of 10%. For the asymmetric admixture model (CGF) (Fig. 1c), we divided the analysis into two sub-models. If population 1 was a gene flow recipient, we denoted it as a CGFR model; otherwise we denoted it as a CGFD model. We set the proportions of admixture in CGF model from 20 to 90% in steps of 10%, and we set the admixture time to 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 generations. For the multiple-wave model (Fig. 1d), we considered a scenario of two ancestral populations with two-wave admixture. For simplicity, we assumed that in each wave of admixture the proportions (αi,1 ≤ i ≤ n) were equal. We used four values of admixture proportions: 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5. The admixture time were set as five cases: (a) t2 = 10, T = 20, (b) t2 = 20, T = 40, (c) t2 = 40, T = 60, (d) t2 = 60, T = 80, and (e) t2 = 80, T = 100. Each simulation setting was repeated ten times for a total of 1400 simulations across the four admixture models. MultiWaver 2.0 was applied to the simulated data with the default settings and the results were recorded and summarized.

Application to analysis of real datasets

Several real admixed populations histories were analyzed by our method. First, we applied our method to African Americans. The data for African Americans and reference populations CEU and YRI were obtained from HapMap Project Phase III [26]. Next, we applied our method to reconstruct the population history of Uyghurs and Hazaras. We used the Han and French populations as the proxies for Eastern ancestry and Western ancestry, respectively [4]. Data used in this analysis were obtained from the HGDP dataset. Haplotype phasing was performed by SHAPEIT 2 [32]. Local ancestry was inferred by HAPMIX [33]. MultiWaver 2.0 was used to select the optimal model and to estimate the admixture time and proportion using tracks longer than 1 cm.

Results

MultiWaver 2.0 performed well in parameter estimation and model selection

With the extensively simulated data, we could systematically evaluate the performance of our method in regard to parameter estimation and model selection. The model was correctly selected in 88% of the simulations. For the simulations using the HI and GA scenarios, our method was able to distinguish the correct model in nearly all simulations; for the CGFR, CGFD, and multiple-wave models, our method identified the correct model with an accuracy of 82.0% (Table 1). We found that the simulations in which our method failed were often those including very recent admixture time and small admixture proportion.

Table 1.

The accuracy of our method in model selection

| Model | Number of simulations | Correct model | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| HI | 200 | 198 | 0.99 |

| GA | 200 | 200 | 1.00 |

| CGFD | 400 | 328 | 0.82 |

| CGFR | 400 | 338 | 0.85 |

| Multiple-wave | 200 | 164 | 0.82 |

| Total | 1400 | 1228 | 0.88 |

Correct model: the number of simulations that could be distinguished as the correct model by Multiwaver 2.0

HI represents hybrid isolation model; GA represents gradual admixture model; CGFD represents continuous gene flow model (population 1 as donor); CGFR represents continuous gene flow model (population 1 as recipient)

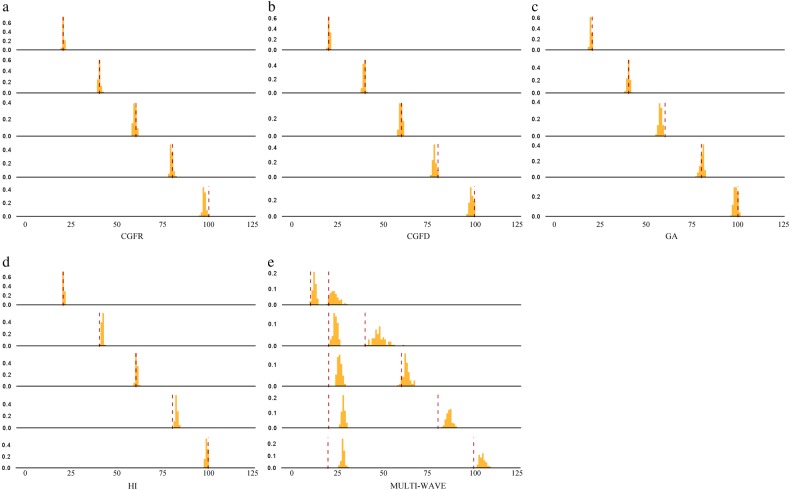

We also evaluated the performance of our method for time estimation. Our method was able to estimate admixture time with high accuracy (Fig. 3). Figure 3 shows one set of simulations and the corresponding bootstrap results for CGFR, CGFD, GA, HI, and multiple-wave models. For the HI, CGF, and GA models, the results were highly consistent with the time simulated, while there was a slight overestimation for the multiple-wave model. We conclude that regardless of model selection or parameters estimated, our method performed well.

Fig. 3.

Admixture time estimated under four different types of admixture models. a CGFR model; b CGFD model; c GA model; d HI model; and e multiple-wave model. The x-coordinate is the admixture time in generations ago, with 0 being the present time. The y-coordinate is the density of admixture time estimated from 100 bootstrap-resampling datasets. There are five subgraphs for each model. Each subgraph represents the result from one simulation assuming a certain admixture time. The red dashed lines represent the given admixture time for the simulation. The admixture proportion was 0.3

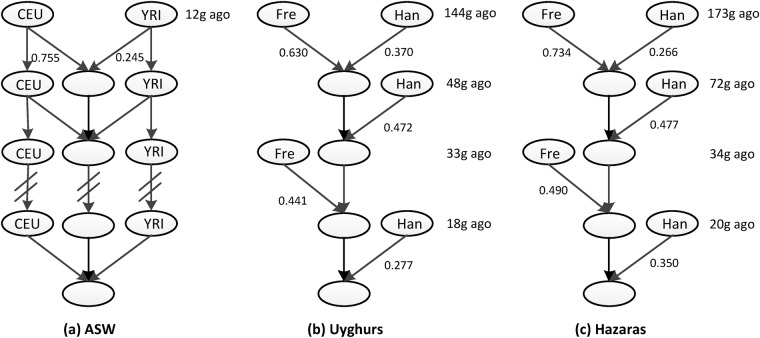

Real data analysis

For African Americans, the program inferred the GA admixture model and the admixture time to be 12 generations (Fig. 4a, Table S1). In our previous study [13, 25], the African American population was inferred as a GA scenario with AdmixInfer and as a two-wave admixture model with MultiWaver. While both results are supported by various historical records, a best-fit model is desirable. The MultiWaver 2.0 program was able to solve this problem using a decision-making framework. We compared the likelihood of the two methods with the BIC and found that the GA model was the most likely scenario. In other words, the GA model appears to be superior to multiple-wave admixture models for African Americans.

Fig. 4.

Inferred admixture history based on analysis of real datasets. Inferred admixture history of a African Americans (ASW), where CEU and YRI were taken as the representative ancestral source populations of ASW; b Uyghurs, and c Hazaras. Han is Han population representing Asian ancestry, Fre is French population representing European ancestry

In addition, we applied our method to reconstruct the admixture histories of Uyghurs and Hazaras. These two admixed populations were inferred as GA types by AdmixInfer [13] and inferred as multiple-wave types by MultiWaver [25]. The results of MultiWaver 2.0 confirmed that the admixture pattern of Uyghurs and Hazaras followed a multiple-wave admixture model, rather than a GA or a CGF model (Fig. 4b, c, Table S1).

Discussion

MultiWaver 2.0 is an improved version of MultiWaver in that it can consider both discrete and continuous admixture models simultaneously. In MultiWaver 2.0, we apply the principles of the BIC to select the optimal model. Simulation studies suggest that our method is precise and efficient in model selection and parameter estimation.

Admixture history of a real population is often very complex. Previous methods have always required some strong pre-knowledge of the admixture pattern. If the admixture pattern is wrongly selected, the inferred admixture history may deviate from the actual history. Here, we provide a general framework to try to deal with this problem. MultiWaver 2.0 can automatically select the best-fit model from the candidates. Indeed, when the true admixture histories deviate from any of the given candidate models, our method might not have a good inference. However, the models we provided cover most admixture cases in the real data analysis and the framework of our method is much more flexible. In the future, if a new representative model is proposed, it can be easily introduced into this framework.

However, some problems remain. First, we found that the penalty for the number of parameters in the BIC method was not sufficient for our method of model selection; thus, the simulations under the CGFR and CGFD models were often wrongly determined as multiple-wave models. This was especially true for population with recent admixture time and small admixture proportion. Second, overestimation occurred for the admixture time when inferring admixture history under the multiple-wave model. This problem also occurred in MultiWaver. However, the overestimation was related to the admixture time and the admixture proportion of each wave. In our previous study, we used this relationship to adjust the estimation of admixture time [25].

Similar to other ancestral tracts information-based methods, our method is sensitive to the accuracy of local ancestry inference (LAI). For existing LAI methods, short ancestral tracts are very difficult to detect. To remove the influence of short ancestral segments, we suggest using only the ancestral tracks longer than a certain threshold C in our software. Besides the small tracts effect, the admixture model used by the LAI method is also a strong priori assumption. The history inference results might tend to be similar to those of the LAI model. To overcome this problem, joint inference of ancestral tracts and admixed history may be implemented in the future.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program (XDB13040100) and Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences (QYZDJ-SSW-SYS009) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2017JBM071, 2017YJS197), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (91731303, 31771388, 11426237, and 31711530221), the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (31525014), the Program of Shanghai Academic Research Leader (16XD1404700), the National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFC0906403), and Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (2017SHZDZX01), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2017M620595), the National Center for Mathematics and Interdisciplinary Sciences of CAS. SX also gratefully acknowledges the support of the National Program for Top-Notch Young Innovative Talents of the “Wanren Jihua” Project.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Zhiming Ma, Email: mazm@amt.ac.cn.

Shuhua Xu, Phone: +86-21-549-20479, Email: xushua@picb.ac.cn.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41431-018-0259-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Yuan K, Zhou Y, Ni X, Wang Y, Liu C, Xu S. Models, methods and tools for ancestry inference and admixture analysis. Quant Biol. 2017;5:236–50. doi: 10.1007/s40484-017-0117-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu S, Huang W, Qian J, Jin L. Analysis of genomic admixture in Uyghur and its implication in mapping strategy. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:883–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patterson Nick, Moorjani Priya, Luo Yontao, Mallick Swapan, Rohland Nadin, Zhan Yiping, Genschoreck Teri, Webster Teresa, Reich David. Ancient Admixture in Human History. Genetics. 2012;192(3):1065–1093. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.145037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loh Po-Ru, Lipson Mark, Patterson Nick, Moorjani Priya, Pickrell Joseph K., Reich David, Berger Bonnie. Inferring Admixture Histories of Human Populations Using Linkage Disequilibrium. Genetics. 2013;193(4):1233–1254. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.147330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pickrell J. K., Patterson N., Loh P.-R., Lipson M., Berger B., Stoneking M., Pakendorf B., Reich D. Ancient west Eurasian ancestry in southern and eastern Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111(7):2632–2637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313787111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou Y, Yuan K, Yu Y, Ni X, Xie P, Xing E et al. Inference of multiple-wave population admixture by modeling decay of linkage disequilibrium with polynomial functions. Heredity. 2017;118:503–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Pugach I, Matveyev R, Wollstein A, Kayser M, Stoneking M. Dating the age of admixture via wavelet transform analysis of genome-wide data. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R19. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-2-r19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin W, Li R, Zhou Y, Xu S. Distribution of ancestral chromosomal segments in admixed genomes and its implications for inferring population history and admixture mapping. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:930–7. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin W, Wang S, Wang H, Jin L, Xu S. Exploring population admixture dynamics via empirical and simulated genome-wide distribution of ancestral chromosomal segments. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:849–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gravel S. Population genetics models of local ancestry. Genetics. 2012;191:607–19. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.139808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pool JE, Nielsen R. Inference of historical changes in migration rate from the lengths of migrant tracts. Genetics. 2009;181:711–9. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.098095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hellenthal G., Busby G. B. J., Band G., Wilson J. F., Capelli C., Falush D., Myers S. A Genetic Atlas of Human Admixture History. Science. 2014;343(6172):747–751. doi: 10.1126/science.1243518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ni X, Yang X, Guo W, Yuan K, Zhou Y, Ma Z et al. Length Distribution of Ancestral Tracks under a General Admixture Model and Its Applications in Population History Inference. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Pugach Irina, Matveev Rostislav, Spitsyn Viktor, Makarov Sergey, Novgorodov Innokentiy, Osakovsky Vladimir, Stoneking Mark, Pakendorf Brigitte. The Complex Admixture History and Recent Southern Origins of Siberian Populations. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2016;33(7):1777–1795. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng Qidi, Lu Yan, Ni Xumin, Yuan Kai, Yang Yajun, Yang Xiong, Liu Chang, Lou Haiyi, Ning Zhilin, Wang Yuchen, Lu Dongsheng, Zhang Chao, Zhou Ying, Shi Meng, Tian Lei, Wang Xiaoji, Zhang Xi, Li Jing, Khan Asifullah, Guan Yaqun, Tang Kun, Wang Sijia, Xu Shuhua. Genetic History of Xinjiang’s Uyghurs Suggests Bronze Age Multiple-Way Contacts in Eurasia. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2017;34(10):2572–2582. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kidd Jeffrey M., Gravel Simon, Byrnes Jake, Moreno-Estrada Andres, Musharoff Shaila, Bryc Katarzyna, Degenhardt Jeremiah D., Brisbin Abra, Sheth Vrunda, Chen Rong, McLaughlin Stephen F., Peckham Heather E., Omberg Larsson, Bormann Chung Christina A., Stanley Sarah, Pearlstein Kevin, Levandowsky Elizabeth, Acevedo-Acevedo Suehelay, Auton Adam, Keinan Alon, Acuña-Alonzo Victor, Barquera-Lozano Rodrigo, Canizales-Quinteros Samuel, Eng Celeste, Burchard Esteban G., Russell Archie, Reynolds Andy, Clark Andrew G., Reese Martin G., Lincoln Stephen E., Butte Atul J., De La Vega Francisco M., Bustamante Carlos D. Population Genetic Inference from Personal Genome Data: Impact of Ancestry and Admixture on Human Genomic Variation. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2012;91(4):660–671. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baharian Soheil, Barakatt Maxime, Gignoux Christopher R., Shringarpure Suyash, Errington Jacob, Blot William J., Bustamante Carlos D., Kenny Eimear E., Williams Scott M., Aldrich Melinda C., Gravel Simon. The Great Migration and African-American Genomic Diversity. PLOS Genetics. 2016;12(5):e1006059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moorjani Priya, Patterson Nick, Hirschhorn Joel N., Keinan Alon, Hao Li, Atzmon Gil, Burns Edward, Ostrer Harry, Price Alkes L., Reich David. The History of African Gene Flow into Southern Europeans, Levantines, and Jews. PLoS Genetics. 2011;7(4):e1001373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Price Alkes L., Patterson Nick, Yu Fuli, Cox David R., Waliszewska Alicja, McDonald Gavin J., Tandon Arti, Schirmer Christine, Neubauer Julie, Bedoya Gabriel, Duque Constanza, Villegas Alberto, Bortolini Maria Catira, Salzano Francisco M., Gallo Carla, Mazzotti Guido, Tello-Ruiz Marcela, Riba Laura, Aguilar-Salinas Carlos A., Canizales-Quinteros Samuel, Menjivar Marta, Klitz William, Henderson Brian, Haiman Christopher A., Winkler Cheryl, Tusie-Luna Teresa, Ruiz-Linares Andrés, Reich David. A Genomewide Admixture Map for Latino Populations. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;80(6):1024–1036. doi: 10.1086/518313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian Chao, Hinds David A., Shigeta Russell, Adler Sharon G., Lee Annette, Pahl Madeleine V., Silva Gabriel, Belmont John W., Hanson Robert L., Knowler William C., Gregersen Peter K., Ballinger Dennis G., Seldin Michael F. A Genomewide Single-Nucleotide–Polymorphism Panel for Mexican American Admixture Mapping. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;80(6):1014–1023. doi: 10.1086/513522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Sijia, Ray Nicolas, Rojas Winston, Parra Maria V., Bedoya Gabriel, Gallo Carla, Poletti Giovanni, Mazzotti Guido, Hill Kim, Hurtado Ana M., Camrena Beatriz, Nicolini Humberto, Klitz William, Barrantes Ramiro, Molina Julio A., Freimer Nelson B., Bortolini Maria Cátira, Salzano Francisco M., Petzl-Erler Maria L., Tsuneto Luiza T., Dipierri José E., Alfaro Emma L., Bailliet Graciela, Bianchi Nestor O., Llop Elena, Rothhammer Francisco, Excoffier Laurent, Ruiz-Linares Andrés. Geographic Patterns of Genome Admixture in Latin American Mestizos. PLoS Genetics. 2008;4(3):e1000037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu S, Jin L. A genome-wide analysis of admixture in Uyghurs and a high-density admixture map for disease-gene discovery. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:322–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipson M, Loh PR, Patterson N, Moorjani P, Ko YC, Stoneking M et al. Reconstructing Austronesian population history in Island Southeast Asia. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Bryc K, Durand EY, Macpherson JM, Reich D, Mountain JL. The genetic ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96:37–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ni X, Yuan K, Yang X, Feng Q, Guo W, Ma Z et al. Inference of multiple-wave admixtures by length distribution of ancestral tracks. Heredity. 2018:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.International HapMap C, Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L, Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA et al. Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature. 2010;467:52–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Li J. Z., Absher D. M., Tang H., Southwick A. M., Casto A. M., Ramachandran S., Cann H. M., Barsh G. S., Feldman M., Cavalli-Sforza L. L., Myers R. M. Worldwide Human Relationships Inferred from Genome-Wide Patterns of Variation. Science. 2008;319(5866):1100–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1153717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978;6:461–4. doi: 10.1214/aos/1176344136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wit E, van den Heuvel E, Romeijn JW. ‘All models are wrong…’: an introduction to model uncertainty. Stat Neerl. 2012;66:217–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9574.2012.00530.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J R Stat Soc B.1977:39:1−38.

- 31.Yang X, Ni X, Zhou Y, Guo W, Yuan K, Xu S. AdmixSim: a forward-time simulator for various and complex scenarios of population admixture. bioRxiv. 2016:037135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Delaneau O, Marchini J, Zagury JF. A linear complexity phasing method for thousands of genomes. Nat Methods. 2012;9:179–81. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Price Alkes L., Tandon Arti, Patterson Nick, Barnes Kathleen C., Rafaels Nicholas, Ruczinski Ingo, Beaty Terri H., Mathias Rasika, Reich David, Myers Simon. Sensitive Detection of Chromosomal Segments of Distinct Ancestry in Admixed Populations. PLoS Genetics. 2009;5(6):e1000519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.