Abstract

Saudi Arabia is witnessing a healthcare transformation to face the challenges of the increased burden of noncommunicable diseases and to maintain the quality of healthcare services. However, in Saudi Arabia, where low back and neck pain, depressive disorders, migraine, diabetes, and anxiety disorders cause the most disability, a broader way of integrative health approach is needed to foster healthy lives and promote well-being for all ages. In the presence of the advanced modern medicine healthcare system in Saudi Arabia, the traditional medicine healing system is being used by a substantial proportion of Saudis but like a shadow healthcare system. This phenomenon of using two healthcare systems reflects a need for an integrative healthcare system. Integrative medicine or approach is about bringing traditional, complementary, and modern medicine in a harmonized system of healthcare which can give a high return and save cost. The rationale behind integrative medicine is to include the best practices of both conventional and complementary therapy, uniting these practices into an integrative approach. Pain management, care of cancer patients, and behavior change are among the leading areas of integration models that should be included in healthcare transformation in Saudi Arabia. Investment in behavior change and well-being outside the boundaries of the healthcare system in the Saudi 2030 vision will have more impact on health and wellness of the Saudi citizen in the face of the epidemics of the lifestyle diseases. Models of integrative medicine during the healthcare transformation can be developed, evaluated, and replicated.

Keywords: Cupping, Integrative medicine, Saudi Arabia, Healthcare transformation

1. Introduction

Saudi Arabia, officially known as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, is the second largest Arab state and comprises the majority of the Arabian Peninsula. The population of the country is estimated to be around 33.55 million in 2018. One-third are expatriates.1 The proportion of Saudi nationals who are less than 15 years is 30.4% of the total Saudi nationals. The proportion of the Saudi nationals who are at least 65 years old is 4.1% of the total Saudi nationals.

As a part of a global movement, interest in well-being behavior and the use of traditional and complementary therapy have grown considerably in recent years not only among the public,2, 3 but also among medical professions,4 decision-makers, and researchers5 in Saudi Arabia. The increased burden of chronic illness6 and the search for an alternative healing system to respond to the unmet need in modern medicine is an important motivation.7, 8

Because of widespread awareness campaigns, a substantial number of Saudi Arabians are now more aware of the benefits of following a healthy lifestyle and healthier dietary habits. The awareness has also emerged as the new generations are becoming digitally connected to the global population and learning the culture of wellness, the advantages of adopting healthy lifestyles and their benefits, and the evolving concept of mind–body medicine. However, this knowledge is not yet accompanied by a practical change in lifestyles even in younger generations, especially among females.9, 10, 11, 12

Investment in healthcare in a country with 50% of the citizens younger than 25 years like Saudi Arabia1 is a challenging opportunity but with an expected high return. Health policies that integrate and coordinate all health disciplines can influence and shape individuals’ health in the face of the epidemic of lifestyle diseases.13, 14

2. Current status of healthcare in Saudi Arabia

2.1. Disease burden

In 2010, noncommunicable diseases and road traffic accidents became the leading causes of death and disability in Saudi Arabia. The leading causes of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) were major depressive disorder, road traffic injuries, and diabetes. In contrast, in 1990, the leading cause of DALYs was preterm birth complications.6 The changing pattern of diseases in Saudi Arabia was a reflection of the changes in lifestyle due to the recent economic growth. The current lifestyle habits are characterized by the low prevalence of physical activity,15 poor dietary behavior, and smoking.16 Leading risk factors attributable to DALYs in 2010 were high body mass index, dietary risk, elevated fasting blood glucose, and physical inactivity.

The change in the epidemiological pattern of diseases driven by the current lifestyle habits will contribute to a continuous increase in the Years Lived with Disability (YLD) in Saudi Arabia.17 Latest health metrics regarding health problems that cause the most disability in Saudi Arabia showed that there was an increase in the proportion of neck and back pain, migraine, diabetes, and depressive and anxiety disorders from 2005 to 2016.18

The current healthcare system cannot cope with present and future burden of lifestyle diseases without spending more in the upstream investment,19 and the use of holistic healthcare approach.

2.2. Healthcare system

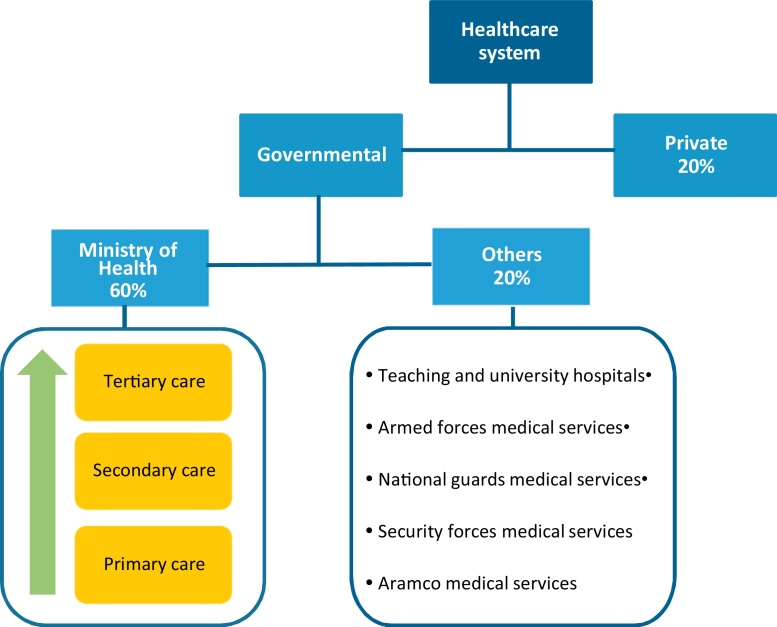

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) has achieved a tremendous improvement in its healthcare system in the past few decades. The national healthcare system is a modern westernized system. Currently, it is primarily owned and operated by the Government through the Ministry of Health (MOH) and other governmental or semipublic healthcare systems. The MOH is responsible for 60% of healthcare services, and the remaining 40% are managed by other semipublic services and the private sector.20

Fig. 1 shows the current structure of the healthcare system in Saudi Arabia.

Fig. 1.

The current structure of the healthcare system in Saudi Arabia.

In recent years, there has been a move toward restructuring healthcare system to privatize public hospitals and introduce insurance coverage for both foreign workers and citizens.21, 22 The share of the private sector in the healthcare system is expected to increase in the near future.

The healthcare system in Saudi Arabia is facing many challenges to maintain quality healthcare services and to avoid a supply gap. The expanding population and the high demand for the free services continue to be a significant challenge to the healthcare system, especially with limited financial resources.23 However, the most significant challenge is that the healthcare system is struggling to keep pace with the increased burden of non-communicable diseases. There is a need to reform the mode of health financing to achieve equitable and efficient healthcare services.

The mode of health financing was the primary aim of healthcare transformation in Saudi Arabia to improve healthcare indicators and to reduce out of pocket spending.24

There is no official traditional healthcare system. Nevertheless, the traditional medicine healing system is being used by the majority of Saudis but like a shadow healthcare system.3, 25

2.3. Current status of traditional and complementary medicine in Saudi Arabia

In Saudi Arabia, there is no traditional healing system similar to east and south Asian countries, like China, Korea, or India, but a collection of traditional regional healing practices emerging from different geographical and cultural origins. However, the terms “Islamic Medicine” and “Prophetic Medicine” are used in Saudi Arabia like other regional and Muslims communities to refer to a group of healing therapies practiced in the Arab and Islamic world within the context of religious influences of Islam.26 While “Islamic Medicine” is open to all practices that are not contradicting with Islamic religion,26, 27 “Prophetic Medicine is only restricted to practices included in the traditions and sayings of the Prophet of Islam.26 Sometimes, the term “Traditional Arabic and Islamic Medicine”28, 29 are used to refer to all the practices in the Arab region and to resolve the confusion between the terms “Arabic Medicine” and “Islamic Medicine”.30, 31

Systematic reviews of multiple regional surveys showed that Traditional Medicine (TM) use ranges from 60 to 75%.3, 32 Religious healings, herbal medicine, cupping therapy, and healing with honey are the leading four therapies in traditional medicine in Saudi Arabia.2, 4, 32 Camel milk33 and cautery34 are also common traditional therapies. Traditional healers are the primary providers of traditional therapies. However, licensed practices like Acupuncture, Osteopathy, Chiropractic, and naturopathy, are provided by licensed practitioners.3, 32 Licensed practitioners offer cupping therapy, which was recently regulated and licensed in Saudi Arabia.35

2.4. Healthcare transformation in Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia is witnessing a healthcare transformation as a part of the Saudi 2030 vision. This transformation aims to improve the quality of healthcare services and to expand privatization of governmental healthcare services. The operational plan includes increasing the private sector contribution spending from the current 25% to 35% in 2020. The plan also includes boosting investment in primary healthcare, health information technology, and training.36 Health insurance will play a significant role in financing the healthcare services.37, 38

However, in Saudi Arabia, where low back and neck pain, depressive disorders, migraine, diabetes, and anxiety disorders cause the most disability,18 a broader way of integrative health approach is needed to foster healthy lives and promote well-being for all ages.39 We need to remember that health is not merely the absence of disease or infirmity but a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being.40 This definition of health cannot be achieved without focusing on the whole person, and making use of all appropriate and evidenced-based therapeutic and lifestyle approaches, healthcare professionals and disciplines to achieve optimal health and healing.39, 41

2.5. Why we need integrative medicine and health

Integrative medicine or approach is about bringing complementary and modern medicine in a harmonized system of healthcare, which can give a high return42 and save cost.43 The inclusion of integrative approaches to health and wellness has grown within healthcare settings in the United States44 and other countries.45 The World Health Organization (WHO) now encourages and supports member states in implementing certain forms of complementary therapies and ensuring their rational use in their national healthcare systems, wellness, and people-centered healthcare. Furthermore, WHO continuously recommends that member states improve the safety and effectiveness of complementary therapies usage through regulation, education, and research, and to integrate complementary medicine practitioners into the health system, as appropriate.41

Complementary therapies or approaches can be included in integrative models of healthcare transformation in Saudi Arabia. The integration model should integrate not only well researched but also culturally appropriate practices.27

A unique advantage of a complementary medicine intervention is its holistic approach, which is best suited to patients who have particular psychological and spiritual needs. Holistic approaches pay attention to these needs, focus on the patient–doctor relationship, and understand the patient's perspective through multimodal concepts. The rationale behind integrative medicine, then, is to include the best practices of both conventional and complementary therapy, uniting these practices into a holistic approach that offers the benefits of both approaches. Pain management,46, 47 care of cancer patients,48 and behavior change are among the leading areas of integration models.

3. The current settings for integrative medicine in Saudi Arabia

The concept of integrative medicine is not currently adopted in the national healthcare system in Saudi Arabia. The current situation of the related policy and regulations, training of traditional medical practitioners, organizational and healthcare infrastructure, and funding and insurance, represent how far we have to work to implement an integrated healthcare system.

3.1. Policy and regulations

Regarding policy and regulations, nothing specific is written in the MOH strategy or policy regarding integrative medicine and health. However, the establishment of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) under the MOH by the council ministers (Resolution 367-9-11-2009),49 was a reflection of a policy that is willing to adopt Traditional and Complementary Medicine (T&CM) into the healthcare system. NCCAM is a reference for all aspects of T&CM in Saudi Arabia.49 In addition to regulations and licensing of T&CM practices, NCCAM is involved in promoting research, training, public awareness, and the authentication of Islamic medicine. The regulatory mission of the NCCAM is fulfilled through coordination with the other health regulatory bodies in Saudi Arabia; The Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA), The Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (SCHS), and local, regional authorities of the MOH. Currently, five therapies are licensed in Saudi Arabia; Acupuncture, Osteopathy, Chiropractic, Naturopathy, and cupping.50 Any products related to the five practices in addition to herbal products are regulated by the SFDA.51

3.2. Training and education

As for training of the providers of T&CM, there is only an official course for cupping providers that is conducted by the NCCAM, and it is one of the requirements for licensing the cupping providers. There is no formal training for other licensed T&CM practices. However, courses taken abroad for the licensed practices in Saudi Arabia can be accredited by The Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (SCFHS) according to specific criteria. There is no separate integrative medicine education for T&CM providers, although courses of T&CM have been introduced for the undergraduate medical schools in a substantial number of Saudi universities.52, 53

3.3. Organizational and healthcare infrastructure

Currently, there is no organizational and healthcare infrastructure in the MOH that can offer integrative healthcare. Few clinics of complementary therapies are available in the MOH, universities, and military hospitals, mainly for research but they can provide services with too.54 The Saudi NCCAM/MOH established three integrated cupping clinics in three secondary care hospitals in three different cities as a model of integrated medicine. The model was for evaluation and research and closed after one year.54

3.4. Funding and insurance

The five licensed practices of T&CM are mainly practiced in the private sector but as parallel and not integrated services. The services are paid for directly by the patient without reimbursement.32, 55 According to the Council of Cooperative Health Insurance in Saudi Arabia (https://www.cchi.gov.sa), traditional and complementary medicine practices are not covered by the national insurance policy.

4. Conclusion

Reforming the mode of healthcare financing should not be the only goal of healthcare transformation in Saudi Arabia. Transformation should also include a move toward integrative health and medicine and to promote the culture of wellness.56 Saudis are more likely to seek healthcare only when they are sick, which may be too late in the face of the lifestyle diseases epidemics.57, 58 More investment is needed in behavior change and to promote self-responsibility because well-being is not only performed by a social and professional health practice but is also informed by our own self-care and resilience.39 Investment in behavior change and well-being outside the boundaries of the healthcare system in the Saudi 2030 vision will have more impact on health and wellness of the Saudi citizen than direct spending on healthcare facilities.

Future practical steps may start with creating advocacy for the concept of integrative medicine and health. In-depth discussions with all the stakeholders to upgrade the settings for implementing the concept of integrative medicine is needed. Proposed areas for development include policy and regulations, training and education, organization and healthcare infrastructure, funding, and insurance. Models of integrative medicine during the healthcare transformation can be developed, evaluated, and replicated. Pain management and integrative oncology may be the ideal models to start with. The western model of integration59, 60, 61 may be the initial choice as it can fit into the current modern healthcare system, then to use it to upgrade the current setting for integrative medicine in Saudi Arabia.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors in their personal capacities. They do not represent the official views of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Saudi Arabia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.TGAS . The General Authority for Statistics (TGAS), Saudi Arabia; Saudi Arabia: 2018. Statistical yearbook of 2016 Riyadh. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elolemy AT, Albedah AM. Public knowledge, attitude and practice of complementary and alternative medicine in Riyadh region, saudi arabia. Oman Med J. 2012;27:20–26. doi: 10.5001/omj.2012.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alrowais NA, Alyousefi NA. The prevalence extent of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) use among Saudis. Saudi Pharm J. 2017;25:306–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albedah AM, El-Olemy AT, Khalil MK. Knowledge and attitude of health professionals in the Riyadh region, Saudi Arabia, toward complementary and alternative medicine. J Family Community Med. 2012;19:93–99. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.98290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zyoud SH, Al-Jabi SW, Sweileh WM. Scientific publications from Arab world in leading journals of Integrative and Complementary Medicine: a bibliometric analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15 doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0840-z. 015-0840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Memish ZA, Jaber S, Mokdad AH, AlMazroa MA, Murray CJ, Al Rabeeah AA. Burden of disease, injuries, and risk factors in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 1990–2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;2:140176. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AlBedah AM, Khalil MK. Cancer patients, complementary medicine and unmet needs in Saudi Arabia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:6799. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.15.6799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jazieh AR, Al Sudairy R, Abulkhair O, Alaskar A, Al Safi F, Sheblaq N. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with cancer in Saudi Arabia. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18:1045–1049. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Kadi A, Malik AM, Mansour AE. Rising incidence of obesity in Saudi residents. A threatening challenge for the surgeons. Int J Health Sci. 2018;12:45–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duncan MJ, Al-Hazzaa HM, Al-Nakeeb Y, Al-Sobayel HI, Abahussain NA, Musaiger AO. Anthropometric and lifestyle characteristics of active and inactive Saudi and British adolescents. Am J Hum Biol. 2014;26:635–642. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baig M, Gazzaz ZJ, Gari MA, Al-Attallah HG, Al-Jedaani KS, Mesawa AT. Prevalence of obesity and hypertension among University students’ and their knowledge and attitude towards risk factors of Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Pak J Med Sci. 2015;31:816–820. doi: 10.12669/pjms.314.7953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khabaz MN, Bakarman MA, Baig M, Ghabrah TM, Gari MA, Butt NS. Dietary habits, lifestyle pattern and obesity among young Saudi university students. J Pak Med Assoc. 2017;67:1541–1546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baumann S, Toft U, Aadahl M, Jorgensen T, Pisinger C. The long-term effect of a population-based life-style intervention on smoking and alcohol consumption. The Inter99 Study – a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2015;110:1853–1860. doi: 10.1111/add.13052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lhachimi SK, Nusselder WJ, Smit HA, Baili P, Bennett K, Fernandez E. Potential health gains and health losses in eleven EU countries attainable through feasible prevalences of the life-style related risk factors alcohol, BMI, and smoking: a quantitative health impact assessment. BMC Public Health. 2016;16 doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3299-z. 016-3299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Nozha MM, Al-Hazzaa HM, Arafah MR, Al-Khadra A, Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Maatouq MA. Prevalence of physical activity and inactivity among Saudis aged 30-70 years. A population-based cross-sectional study. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:559–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Nozha MM, Al-Mazrou YY, Arafah MR, Al-Maatouq MA, Khalil MZ, Khan NB. Smoking in Saudi Arabia and its relation to coronary artery disease. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 2009;21:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jsha.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1545–1602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.IHME. Health Metrics for Saudi Arabia. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Available at: http://www.healthdata.org/saudi-arabia. Accessed 15 May 2018, 2018.

- 19.Khalil M, Nadrah HM, Al-Yahia OA, Al-Segul A. Upstream investment in health care: national and regional perspectives. J Fam Commun Med. 2005;12:55–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colliers International. 2012. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia healthcare overview. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walston S, Al-Harbi Y, Al-Omar B. The changing face of healthcare in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:243–250. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2008.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khaliq AA. The Saudi health care system: a view from the minaret. World Health Popul. 2012;13:52–64. doi: 10.12927/whp.2012.22875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almalki M, Fitzgerald G, Clark M. Health care system in Saudi Arabia: an overview. East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17:784–793. doi: 10.26719/2011.17.10.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alkhamis A, Hassan A, Cosgrove P. Financing healthcare in Gulf Cooperation Council countries: a focus on Saudi Arabia. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2014;29:e64–e82. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.AlBedah AM. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients in Saudi Arabia: a paradox in healthcare. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19:918–919. doi: 10.1089/acm.2013.0162. Epub 2013 Apr 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monette M. The medicine of the prophet. CMAJ. 2012;184:E649–E650. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4228. Epub 2012 Aug 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khalil MKM. Importing well-researched practices from other traditions: thoughts from a conservative society. J Altern Complement Med. 2017;23:829–830. doi: 10.1089/acm.2017.0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azaizeh H, Saad B, Cooper E, Said O. Traditional Arabic and Islamic medicine, a re-emerging health aid. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2010;7:419–424. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.AlRawi SN, Khidir A, Elnashar MS, Abdelrahim HA, Killawi AK, Hammoud MM. Traditional Arabic & Islamic medicine: validation and empirical assessment of a conceptual model in Qatar. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17:017–1639. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1639-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albinali HA. Arab or Islamic medicine? Heart Views. 2013;14:41–42. doi: 10.4103/1995-705X.107124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hajar R. The air of history. Part III: The golden age in Arab Islamic medicine an introduction. Heart Views. 2013;14:43–46. doi: 10.4103/1995-705X.107125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.AlBedah AM, Khalil MK, Elolemy AT, Al Mudaiheem AA, Al Eidi S, Al-Yahia OA. The use of and out-of-pocket spending on complementary and alternative medicine in Qassim province, Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2013;33:282–289. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2013.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abuelgasim KA, Alsharhan Y, Alenzi T, Alhazzani A, Ali YZ, Jazieh AR. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with cancer: a cross-sectional survey in Saudi Arabia. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;18:018–2150. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2150-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohammad Y, Al-Ahmari A, Al-Dashash F, Al-Hussain F, Al-Masnour F, Masoud A. Pattern of traditional medicine use by adult Saudi patients with neurological disorders. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:015–0623. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0623-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khalil MKM, Al-Eidi S, Al-Qaed M, AlSanad S. Cupping therapy (Hijamah) in Saudi Arabia: from control to integration. Int Med Res., 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.vision2030. National Transformation Program 2020. VISION 2030.GOV.SA [Electronic]. Available at: http://vision2030.gov.sa/sites/default/files/NTP_En.pdf. Accessed 18 April, 2018, 2018.

- 37.Al-Hanawi MK, Vaidya K, Alsharqi O, Onwujekwe O. Investigating the willingness to pay for a contributory National Health Insurance Scheme in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional stated preference approach. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2018;16:259–271. doi: 10.1007/s40258-017-0366-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Sharqi O.Z., Abdullah M.T. ``Diagnosing" Saudi health reforms: is NHIS the right "prescription"? Int J Health Plann Manage. 2013;28:308–319. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Organizing Committee WCoIMaH The Berlin agreement: self-responsibility and social action in practicing and fostering integrative medicine and health globally. J Alternat Complement Med. 2017;23:2. [Google Scholar]

- 40.WHO. Constitution of WHO: principles. Available at: http://www.who.int/about/mission/en.

- 41.WHO. WHO traditional medicine strategy: 2014-2023. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/92455/1/9789241506090_eng.pdf. Accessed 3 December, 2017.

- 42.Russo R, Diener I, Stitcher M. The low risk and high return of integrative health services. Healthc Financ Manage. 2015;69:114–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kligler B, Homel P, Harrison LB, Levenson HD, Kenney JB, Merrell W. Cost savings in inpatient oncology through an integrative medicine approach. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:779–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.NCCIH Integrative Medicine . 2016, June. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Accessed November 29, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rossi E, Vita A, Baccetti S, Di Stefano M, Voller F, Zanobini A. Complementary and alternative medicine for cancer patients: results of the EPAAC survey on integrative oncology centres in Europe. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:1795–1806. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2517-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen L, Michalsen A. Management of chronic pain using complementary and integrative medicine. BMJ. 2017;357 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.la Cour P. Rheumatic disease and complementary-alternative treatments: a qualitative study of patient's experiences. J Clin Rheumatol. 2008;14:332–337. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31817a7e1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dobos GJ, Voiss P, Schwidde I, Choi KE, Paul A, Kirschbaum B. Integrative oncology for breast cancer patients: introduction of an expert-based model. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:1471–2407. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.SBOE. National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine regulation. Bureau of Expert, The Council of Ministers. Available at: https://www.boe.gov.sa/printsystem.aspx?lang=ar&systemid=284&versionid=264. Accessed 22 May 2018, 2018.

- 50.MOH. MOH Approves licenses for cupping. MOH. 23 February 2015 Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/News/Pages/News-2015-02-17-002.aspx. Accessed 18 aPRIL 2018, 2018.

- 51.WHO . WHO; Genev: 2001. Legal status of traditional medicine and complementary/alternative medicine: a worldwide review. Accessed 22 May, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Al Mansour MA, Al-Bedah AM, AlRukban MO, Elsubai IS, Mohamed EY, El Olemy AT. Medical students’ knowledge, attitude, and practice of complementary and alternative medicine: a pre-and post-exposure survey in Majmaah University, Saudi Arabia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:407–420. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S82306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Al-Rukban MO, AlBedah AM, Khalil MK, El-Olemy AT, Khalil AA, Alrasheid MH. Status of complementary and alternative medicine in the curricula of health colleges in Saudi Arabia. Complement Ther Med. 2012;20:334–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.AlBedah Abdulla MK. Using research model to integrate Cupping therapy in the conventional health care system in Saudi Arabia.8th Annual International Congress of Complementary Medicine Research. Forschende Komplementarmedizin/ Research in Complementary Medicine. 2013, April;20 (S1 - Abstract 318) [Google Scholar]

- 55.CCHI. the unified general insurance document. Council of Cooperative Health Insurance. Available at: http://www.cchi.gov.sa/AboutCCHI/Rules/document/ملحق%20رقم%201%20الوثيقة.pdf. Accessed 18 April 2018, 2018.

- 56.Khalil M.K.M. Integrative medicine: the imperative for health justice in the other side of the world. J Altern Complement Med. 2018;24(6):613. doi: 10.1089/acm.2018.0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.El Bcheraoui C, Tuffaha M, Daoud F, Kravitz H, AlMazroa MA, Al Saeedi M. Access and barriers to healthcare in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013: findings from a national multistage survey. BMJ Open. 2015;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007801. 2015-007801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arena R, Lavie CJ, Hivert MF, Williams MA, Briggs PD, Guazzi M. Who will deliver comprehensive healthy lifestyle interventions to combat non-communicable disease? Introducing the healthy lifestyle practitioner discipline. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2016;14:15–22. doi: 10.1586/14779072.2016.1107477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dobos GJ, Kirschbaum B, Choi KE. The Western model of integrative oncology: the contribution of Chinese medicine. Chin J Integr Med. 2012;18:643–651. doi: 10.1007/s11655-012-1200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eisenberg DM, Buring JE, Hrbek AL, Davis RB, Connelly MT, Cherkin DC. A model of integrative care for low-back pain. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18:354–362. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Petri RP, Jr, Delgado RE. Integrative medicine experience in the U.S. Department of Defense. Med Acupunct. 2015;27:328–334. doi: 10.1089/acu.2014.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]