Abstract

AlkB homolog 5 (Alkbh5) is one of nine members of the AlkB family, which are nonheme Fe2+/α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases that catalyze the oxidative demethylation of modified nucleotides and amino acids. Alkbh5 is highly selective for the N6-methyladenosine modification, an epigenetic mark that has spawned significant biological and pharmacological interest because of its involvement in important physiological processes, such as carcinogenesis and stem cell differentiation. Herein, we investigate the structure and dynamics of human Alkbh5 in solution. By using 15N and 13Cmethyl relaxation dispersion and 15N-R1 and R1ρ NMR experiments, we show that the active site of apo Alkbh5 experiences conformational dynamics on multiple timescales. Consistent with this observation, backbone amide residual dipolar couplings measured for Alkbh5 in phage pf1 are inconsistent with the static crystal structure of the enzyme. We developed a simple approach that combines residual dipolar coupling data and accelerated molecular dynamics simulations to calculate a conformational ensemble of Alkbh5 that is fully consistent with the experimental NMR data. Our structural model reveals that Alkbh5 is more disordered in solution than what is observed in the crystal state and undergoes breathing motions that expand the active site and allow access to α-ketoglutarate. Disordered-to-ordered conformational changes induced by sequential substrate/cofactor binding events have been often invoked to interpret biochemical data on the activity and specificity of AlkB proteins. The structural ensemble reported in this work provides the first atomic-resolution model of an AlkB protein in its disordered conformational state to our knowledge.

Introduction

AlkB homolog 5 (Alkbh5) is an oncoprotein whose overexpression has been linked to the development of various types of cancer, including leukemia, breast, and brain cancer (1, 2, 3). Alkbh5 belongs to the nonheme Fe2+- and α-ketoglutarate (αKG)-dependent AlkB dioxygenases and catalyzes oxidative demethylation of single-stranded RNAs (4). Although several different methyl modifications have been described and cataloged in nucleic acids (5), Alkbh5 specifically demethylates N6-methyladenosine (m6A), with little to no activity for other methylated nucleotides (6, 7). m6A is the most abundant internal modification of eukaryotic mRNA and long-noncoding RNA (8). In addition, m6A has been observed in the RNA of numerous viruses (9). In eukaryotes, the m6A modification is installed by a methyl transfer machinery comprising three proteins (METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP) (10, 11, 12) and removed by the fat-mass- and obesity-associated FTO protein and/or Alkbh5 (4, 13). The dynamic character of these mRNA modifications is thought to regulate gene expression in response to external stimuli and to influence various physiological processes such as development and differentiation of embryonic stem cells, fertility, and the circadian cycle (14, 15, 16, 17).

AlkB dioxygenases were shown to be plastic and dynamic proteins in which a transition from an inactive (disordered) state to an active (ordered) conformation is achieved through a concerted mechanism of ordered substrate/cofactor bindings and structural rearrangements within the enzyme (18). Although the disordered-to-ordered transition is thought to control important steps in the enzyme life cycle, including coupling between successive chemical steps (19), sequestration of a highly reactive enzyme-bound oxyferryl intermediate (18), and product release (20), an accurate structural model for the disordered state has not been obtained yet. Indeed, although there is now a wealth of crystallographic studies on AlkB dioxygenases in complex with different substrates, inhibitors, and cofactors, there are very few atomic-resolution structural analyses on apo AlkB proteins in the literature. To date, the crystal structures of human Alkbh5 obtained by Aik et al. (PDB: 4NJ4) (21) and Feng et al. (PDB: 4O7X) (22) are the only structures of AlkB proteins in the apo form listed in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Interestingly, these structures are nearly indistinguishable from the structure of Alkbh5 in complex with Mn2+ and αKG (heavy-atom root mean-square deviation = 1.9 Å; PDB: 4NRO) (22). This finding is in stark contrast with previous biophysical investigations on the Escherichia coli AlkB protein, indicating that sequential binding of Fe2+-, αKG-, O2-, and m6A-containing oligonucleotides promotes gradual transition from a disordered state to a catalytically competent ordered conformation (18).

Here, we develop a protocol that combines residual dipolar coupling (RDC) NMR data (23) and accelerated molecular dynamics (aMD) simulations (24) to obtain an atomic-resolution structural model of the apo human Alkbh5 in solution. Our data reveal that the active site of Alkbh5 is more disordered than what is observed in the x-ray structure and undergoes breathing motions that expand the αKG binding pocket and allow access for the small molecule substrate. We expect the combined aMD/NMR protocol developed here to be transferable to other dynamic proteins and to enable future investigations on the role played by conformational dynamics in determining the activity and substrate selectivity of Alkbh5.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

All the experiments have been run on a truncated version of the human Alkbh5 comprising residues 66–292. This truncated construct was used in previous crystallographic investigations on the human Alkbh5 (21, 22) and was reported to retain the enzymatic activity of the full-length protein. Alkbh5 was expressed and purified as previously described (25). U-[2H,15N]/Ile(δ1)-13CH3/Val,Leu-(13CH3/12C2H3)-labeled and U-[2H,15N,13C] Ile(δ1)-(13CH3); Leu,Val-(13CH3/12CD3)]-labeled Alkbh5 samples were prepared following standard protocols for specific isotopic labeling of the methyl groups of Ile, Leu, and Val side chains (26). The ability of our purified Alkbh5 construct to catalyze demethylation of m6A was tested in vitro as previously described (21). Briefly, a 50 μL total reaction volume containing 4 μM Alkbh5, 10 μM 5-mer single-stranded DNA with the sequence 5′-GG(m6A)-CT-3′ (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ), 300 μM αKG, 150 μM Fe(II) sulfate complex, 2 mM L-ascorbate, and 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) was incubated at room temperature for 20 min. After the incubation period, 2 μL aliquots were transferred from the reaction mixture and quenched by 2 μL 20% (v/v) formic acid. 1 μL of each quenched sample was diluted with 1 μL of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization matrix comprised of a 2:1 part ratio of 0.5 M 2,4,6-trihydroxyacetophenone (dissolved in ethanol) and 0.1 M ammonium citrate dibasic (dissolved in water), respectively. Spots were loaded with 0.5 μL of the sample followed by 0.5 μL of the matrix, and the demethylation of the modified substrate by Alkbh5 was analyzed using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. Results are shown in Fig. S1.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR samples were prepared in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 1× protease inhibitor (EDTA-free), 0.02% (w/v) NaN3, and 90% H2O/10% D2O (v/v). Protein concentration was 0.3–0.6 mM.

All NMR spectra were acquired on Bruker (Billerica, MA) 600 and 800 MHz spectrometers equipped with Z-shielded gradient triple resonance cryoprobes. Spectra were processed and analyzed using the programs NMRPipe (27) and SPARKY (http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/home/sparky), respectively. 1H-15N-correlated spectra were assigned based on previously deposited assignment for the human Alkbh5 (Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank: 27413). Assignment of the 1H-13Cmethyl correlations was performed using out-and-back experiments (28) and reported in Fig. S2.

Backbone amide 1DNH RDCs were measured at 25°C by taking the difference in 1JNH scalar couplings in aligned and isotropic media. The alignment media employed was phage pf1 (8 mg/mL; ASLA Biotech, Riga, Latvia) (29), and 1JNH couplings were measured using the amide RDCs by TROSY pulse scheme (30). SVD analysis of RDCs was carried out using Xplor-NIH (31). Back-calculation of RDCs from conformational ensembles was done using the following equation:

| (1) |

where θ is the angle formed between the internuclear bond vector of the amide group of residue i and the z axis of the alignment tensor, ϕ is the angle between the xy plane projection of the internuclear bond vector and the x axis, and Dk is the magnitude of the alignment tensor for ensemble member k multiplied by its fractional population in the ensemble (32). The full set of 188 RDCs was used in the optimization of the alignment tensor. The MATLAB script used for RDC fitting to the ensemble is available for download at http://group.chem.iastate.edu/Venditti/downloads.html.

It is important to notice that Eq. 1 predicts that the contribution of each ensemble member to the experimental RDCs is scaled by the alignment strength and by the fractional populations. Therefore, back-calculation of the RDCs using Eq. 1 does not allow to determine populations for the ensemble members.

15N-R1 and R1ρ experiments were carried out at 25°C and 1H frequency of 800 MHz, using heat-compensated pulse schemes with a TROSY readout (33). The spin-lock field for the R1ρ experiment was set to 1 kHz. Decay durations were 0, 80, 200, 320, 440, 560, 720, and 840 ms for R1 and 8, 56, 96, 200, 312, 432, 560, 696, and 800 ms for R1ρ. R1 and R1ρ values were determined by fitting time-dependent exponential restoration of peak intensities at increasing relaxation delays. R2 values were extracted from the measured R1 and R1ρ values.

15N and 13Cmethyl relaxation dispersion experiments were conducted at 15, 20, and 25°C using a pulse sequence that measures the exchange contribution for the TROSY component of the 15N magnetization (34) or a pulse scheme for 13C single-quantum CPMG relaxation dispersion described by Kay and co-workers (35). Off-resonance effects and pulse imperfections were minimized using a four-pulse phase scheme (36). Experiments were performed at 600 and 800 MHz with a fixed relaxation delay but a changing number of refocusing pulses to achieve different effective CPMG fields (37). The transverse relaxation periods were set to 60 and 30 ms for the 15N and 13Cmethyl experiments, respectively. The resulting relaxation dispersion curves were fit to a two-state exchange model using the Carver-Richards equation (38).

Disulfide bridge investigation by cysteine alkylation

For cysteine disulfide bridge studies, Alkbh5 was investigated in the apo, αKG-bound, and αKG/DNA-bound forms. To mimic physiological conditions, samples were prepared at an enzyme concentration of ∼50 μM in a solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DTT (39). For studies investigating the ligated complex, 500 μM αKG was used in addition to 500 μM Mn2+. The single-stranded DNA substrate with the sequence 5′-GG(m6A)CT-3′ (GenScript) was used at a concentration of 100 μM to explore Alkbh5 in the substrate-bound form. Alkbh5 was analyzed by a Q Exactive Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap Tandem Mass Spectrometer (LC-MS/MS) (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and the original mass deconvoluted both manually and using Thermo Protein Deconvolution software. IAM was then added to the sample to a final concentration of 15 mM and allowed to react in the dark at room temperature for 30 min before being reanalyzed by LC-MS/MS. IAM readily reacts with solvent-accessible thiols, including those found within proteins, resulting in a mass shift of +57 Da per alkylation event (40).

aMD simulation

A 200 ns Gaussian accelerated molecular dynamics (GaMD) simulation (41) was performed in explicit solvent starting from the x-ray structure of apo Alkbh5 (PDB: 4NJ4) by using the Amber 16 package (42) and the Amber ff14sb force field (43).

Missing residues from the x-ray structure (fragment 145–149) were modeled using the software Modeler (44). The starting structure was centered in a truncated octahedron, and the initial shortest distance between the protein atoms and the box boundaries was set to 10 Å. Then, an optimal amount of counterions was added to generate a neutral system. The remaining box volume was filled with TIP3P-type water molecules (45). Water and ion positions were minimized with 500 steps of steepest descent plus 500 steps of conjugate gradient by keeping the protein fixed. Then, the coordinates of all water molecules, ions, and modeled residues were minimized with 500 steps of steepest descent plus 500 steps of conjugate gradient by keeping the x-ray portion of the protein fixed. Finally, the entire system was energy minimized with 1500 steps of steepest descent followed by 1000 steps of conjugate gradient minimization.

The system was first equilibrated in a 1 ns run in which the temperature was gradually raised from 0 to 310 K, followed by a 5 ns run in which the temperature was held constant (310 K). Hence, the equilibrated system was simulated by keeping the temperature (310 K) and pressure (1 atm) constant. Episodic boundary conditions were applied and bonds were restrained with the SHAKE algorithm (46). An integration step of 2 fs was used. Weak coupling to an external pressure and temperature bath was used (47). Particle mesh Ewald summation (48), with a cutoff of 10 Å for long-range interactions, was used to treat electrostatic interactions. Boost parameters for the total and dihedral energies of the system were optimized during a 2 ns conventional MD (cMD) followed by 8 ns GaMD. Finally, 200 ns of GaMD were run at 310 K and 1 atm.

The backbone root mean square deviation calculated over the final GaMD run (Fig. S3) levels off after an equilibration period of ∼20 ns. Thus, the clustering analysis of the trajectory was carried out from 60 ns onward. Clustering of the GaMD trajectory was performed in Amber using the CPPTRAJ tool (49) and the average linkage clustering algorithm (50).

Results

NMR chemical shift and RDC analysis of Alkbh5

Backbone amide (1DNH) RDCs for uniformly 15N/2H-labeled Alkbh5, aligned in a dilute liquid crystalline medium of phage pf1 (29), were measured for well-resolved 1HN/15N crosspeaks in the 1H-15N transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy (TROSY) correlation spectrum (51) using the amide RDCs by TROSY technique (30). 1DNH RDCs were used to investigate structural differences between solution and x-ray structures of Alkbh5. RDCs measure the orientation of bond vectors relative to an external alignment tensor and therefore provide a very sensitive indicator of structural quality (52).

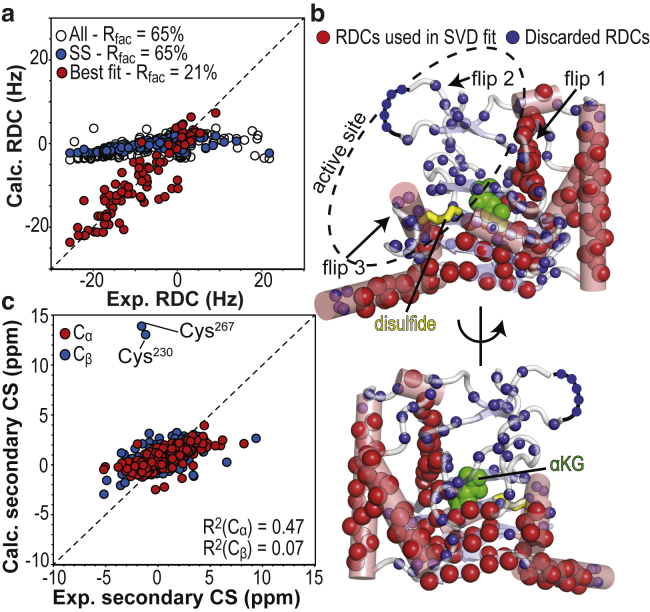

Singular value decomposition (SVD) fitting of the experimental 1DNH RDC to the coordinates of the apo Alkbh5 x-ray structure (PDB: 4NJ4) yielded an R-factor of ∼65% (Fig. 1 a; Table 1), which indicates poor agreement between RDC data and 3D structure. To avoid any structural noise that may result from flexible regions of the enzyme, SVD fitting was then performed using only RDCs from backbone amide groups located in defined secondary structures, producing the same R-factor of ∼65% (Fig. 1 a; Table 1). Interestingly, when the experimental data for all backbone amides from secondary structures located in the active site of Alkbh5 were removed (residues 139–142, 153–156, 201–205, 230–235, and 266–273) and SVD fitting was performed, a good agreement between the x-ray structure and RDC data was observed (R-factor ∼21%; Fig. 1, a and b; Table 1). This finding suggests that the NH-bond vector orientations within the active site of Alkbh5 are misrepresented by the crystal structure (Fig. 1 b), potentially an artifact from crystal lattice packing or crystallization into a low-energy-minima conformation variant of the solution state.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the x-ray structure of apo Alkbh5 with solution NMR data. (a) Agreement between the observed and calculated RDCs obtained by SVD to the coordinates of the x-ray structure of apo Alkbh5 (PDB: 4NJ4 (21)). SVD fitted using the full set of experimental RDCs (open black circle) or RDCs from backbone amides in secondary structures (blue circles) fails to converge (because of the lack of a single orientation of the alignment tensor that satisfies all the experimental data), resulting in predicted RDC values close to zero and high R-factors (see Table 1). Exclusion of RDCs from the protein active site from the SVD analysis results in good agreement between experimental and back-calculated RDCs (red circles). (b) Amide groups whose experimental RDCs are in good agreement with back-calculated values are shown as red spheres on the x-ray structure of apo Alkbh5. Smaller blue spheres indicate the location of RDCs that were not included in the final SVD analysis (i.e., RDCs from loop or active-site residues). Residues that are missing from the x-ray structure (Leu145–Gly149) are indicated by a black curve. The Cys230–Cys267 disulfide bridge is shown as yellow sticks. αKG is modeled in the protein active site and shown as green spheres. (c) Agreement between measured and back-calculated Cα/Cβ secondary chemical shifts. Back-calculation of the NMR chemical shifts was done using Sparta+ (67) and the crystal structure of apo Alkbh5 (21). R2 values for linear regression of the Cα and Cβ data are shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 1.

Backbone Amide 1DNH RDC Analysis of apo Alkbh5

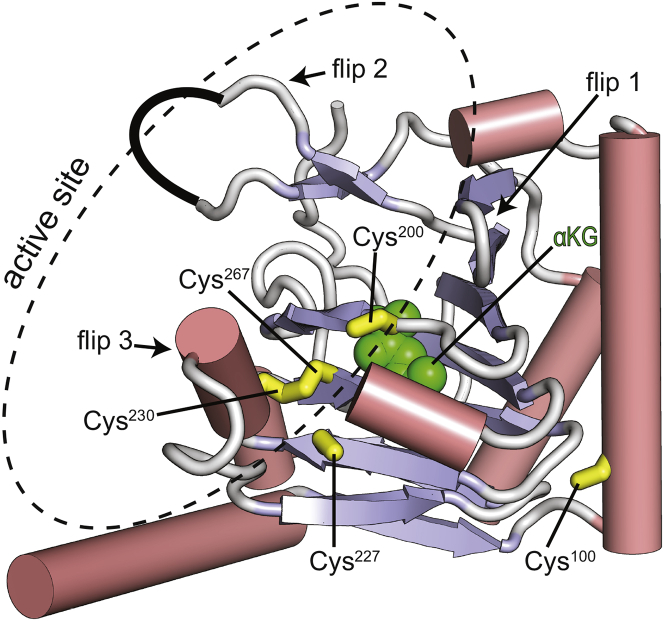

Further insight into the discrepancy between solution and crystal structure was obtained by comparing the Cα/Cβ secondary chemical shifts (calculated from the backbone resonance assignment of apo Alkbh5 reported in the literature (25)) with the ones back-calculated from the crystal structure of the enzyme. Experimental and predicted secondary chemical shifts are in poor agreement (the R2 values for linear regression of the Cα and Cβ data are 0.47 and 0.07, respectively; Fig. 1 c). In particular, the predicted secondary Cβ chemical shifts for residues Cys230 and Cys267 are much larger than what is observed experimentally (Fig. 1 c). Within the crystal structure of Alkbh5, residues Cys230 and Cys267 are involved in a disulfide bridge (Fig. 2) (22, 53), thereby resulting in Cβ chemical shift predictions of an oxidized state. Contrariwise, residues Cys230 and Cys267 possess experimental Cβ chemical shifts indicative of a reduced state, suggesting that the disulfide bridge is absent in solution. Interestingly, the Cys230–Cys267 disulfide bridge packs the Cys230–Lys235 helix from flip 3 (residues 229–242) against the β-strand formed by residues His266–Arg269 from the αKG binding site (Figs. 1 b and 2). Therefore, disruption of this interaction may partially explain the discrepancy between the RDC data measured in solution and back-calculated from the x-ray structure of Akbh5 (Fig. 1 a).

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of apo Alkbh5 (PDB: 4NJ4 (21)) showing the localization of the five cysteine residues (yellow sticks). α-helices are colored pink. β-strands are colored light blue. Missing residues in the x-ray structure (Leu145–Gly149) are indicated by a black curve. αKG is modeled in the protein active site and shown as green spheres. To see this figure in color, go online.

Cysteine alkylation experiments

To further assess the existence of the disulfide bridge between Cys230 and Cys267 in solution, Alkbh5 was allowed to react with the alkylating agent 2-iodoacetamide (IAM) and then analyzed by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The results are summarized in Table 2. IAM alkylates any solvent-accessible cysteine residues in the reduced state, although it does not react with cysteines that are in the oxidized state or that are buried in the protein interior (40). Alkylation by IAM results in a mass shift of +57 Da per alkylated cysteine. It is noteworthy to mention that five cysteines exist within our Alkbh5 construct. When apo Alkbh5 was alkylated by IAM, the deconvoluted mass resulted in a +228 Da mass shift, indicating that four cysteines had been alkylated (Table 2). The fifth cysteine residue was only alkylated after the protein had been denatured by 6 M guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl) (Table 2). These data confirm the absence of the Cys230–Cys267 bridge in solution and indicate that one Cys residue in Alkbh5 is internally buried and therefore inaccessible to alkylating agents. Inspection of the x-ray structure suggests that the buried residue is Cys100 (Fig. 2). To evaluate whether the progressive ordering of the Alkbh5 structure induced by substrate/cofactor binding (18) results in formation of the Cys230–Cys267 bridge, the IAM alkylation study was repeated on the Alkbh5-Mn2+-αKG complex and on the complex formed by Alkbh5, Mn2+, αKG, and a 5-mer single-stranded DNA incorporating the m6A modification (5′-GG(m6A)CT-3′). Upon analysis of the Mn2+/αKG bound enzyme, four cysteine residues were alkylated (Table 2), indicating the lack of a disulfide bridge. Conversely, no mass shift was observed for the Mn2+/αKG/DNA bound enzyme, indicating that no cysteine residues had been alkylated by IAM (Table 2). Inspection of the x-ray structure of Alkbh5 reveals that four cysteines (Cys200, Cys227, Cys230, and Cys267) are located within the nucleotide binding site (Fig. 2). Therefore, DNA binding to Alkbh5 may protect these cysteines from reacting with IAM. Consistent with this hypothesis, denaturation of Alkbh5 with 6 M GuHCl resulted in alkylation of five cysteines (Table 2), reporting on the inability of denatured Alkbh5 to interact with its DNA substrate (note that Akbh5 was incubated with Mn2+, αKG, and DNA for 1 h before addition of 6 M GuHCl). Taken together, the data reported in this section indicate the absence of disulfide bridges in Alkbh5 at all the experimental conditions tested. It is worth mentioning that to simulate the reducing environment of the eukaryotic cell nucleus, the samples analyzed by NMR and LC-MS/MS were prepared in the presence of 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) (39). In the absence of reducing agent, small amounts (<30%) of a monomeric Alkbh5 species incorporating a disulfide bridge were detected by LC-MS/MS analysis (data not shown).

Table 2.

LC-MS/MS Analysis of Disulfide Bridges in Human Alkbh5

| Sample | 6 M GuHCl | −IAM (Da)a | +IAM (Da)b | ΔMass (Da)c | Alkylated Cysd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkbh5 | No | 26,374 | 26,602 | 228 | 4 |

| Yes | 26,374 | 26,659 | 285 | 5 | |

| Alkbh5 + Mn2+ αKG | No | 26,374 | 26,602 | 228 | 4 |

| Yes | 26,374 | 26,659 | 285 | 5 | |

| Alkbh5 + Mn2+ αKG + GG(m6A)CT | No | 26,374 | 26,374 | 0 | 0 |

| Yes | 26,374 | 26,659 | 285 | 5 |

This is the mass of Alkbh5 before addition of the alkylating agent IAM.

This is the mass of Alkbh5 after addition of the alkylating agent IAM.

This is the mass shift caused by addition of IAM.

The number of alkylated cys was calculated by dividing ΔMass by 57 Da (the theoretical mass shift per alkylated Cys) (40).

ps-ns timescale dynamics

ps-ns timescale dynamics in Alkbh5 were investigated by NMR relaxation experiments. Residue-specific 15N-R1 and 15N-R2 values were obtained at 800 MHz and 25°C by acquisition of TROSY-detected R1 and R1ρ experiments (33) on uniformly 15N/2H-labeled Alkbh5. Measured R1 and R2 values are plotted as a function of residue index in Fig. 3 a. As is commonly observed for the majority of folded proteins, R1 and R2 values are similar throughout the sequence. Residues displaying a longitudinal relaxation rate much larger than the average R1 (0.9 ± 0.3 s−1) and a transverse relaxation rate much smaller than the average R2 (23 ± 6 s−1) identify regions of the protein with increased local flexibility.

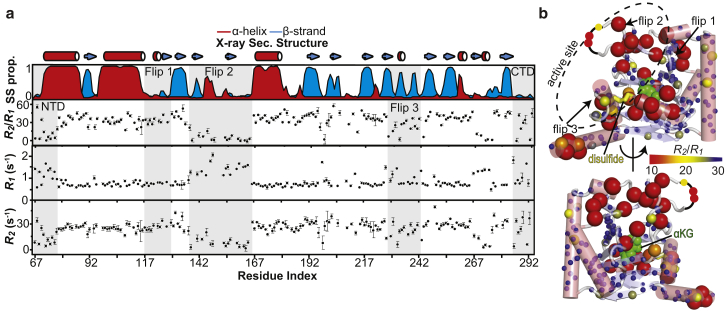

Figure 3.

ps-ns conformational dynamics in apo Alkbh5. (a) 15N R2, R1, and R2/R1 data measured at 800 MHz and 25°C are graphed versus residue index. The secondary structure calculated from the x-ray coordinates using the software MolMol (68) and the secondary structure propensity calculated from the assignment of the NMR backbone resonances using the software Talos+ (69) are shown in the uppermost panel. (b) R2/R1 ratios are plotted on the structure of apo Alkbh5 according to the color bar. Residues that are missing from the x-ray structure are indicated by a black curve. The Cys230–Cys267 disulfide bridge is shown as yellow sticks. αKG is modeled in the protein active site and shown as green spheres. To see this figure in color, go online.

Although direct analysis of R1 and R2 data provides an initial description of local flexibility, ps-ns dynamics in proteins are more conveniently studied in terms of R2/R1 ratios. Global tumbling, with rotational correlation time τm, is the major contribution toward the R1 and R2 values. When global tumbling is the only significant contribution toward motion, then R2/R1 can be used to calculate an initial estimate for τm (54). Residues with lower R2/R1 value, when compared to the average, likely experience additional local motion on the ps-ns timescale (54). The R2/R1 ratios were graphed as a function of residue index (Fig. 3 a) and displayed as a gradient on an x-ray structure of Alkbh5 (Fig. 3 b). The R2/R1 values show a comparable trend to R2 values, with a mean ratio of 31 ± 10, which translates into τm ∼ 13 ns (54). The N-terminus (residues 67–76), flip 2 (residues 136–165), and the unstructured region comprising residues 267–274 exhibit lower than average R2/R1 ratios (16 ± 2, 15 ± 2, and 6 ± 2, respectively), indicating that these regions experience local motion in addition to the overall molecular tumbling (Fig. 3 b). Of note, these structural motifs correspond closely to the regions of the x-ray structure that could not reproduce the experimental RDC data (Fig. 1 b), suggesting that conformational disorder may contribute substantially to the discrepancy between solution and crystal-state data observed above (Fig. 1).

μs-ms timescale dynamics

To investigate conformational dynamics of apo Alkbh5 on the μs-ms timescale, we have used 15N TROSY (34) and 13C single-quantum (35) Carr-Purcell-Meinboom-Gill (CPMG) relaxation dispersion spectroscopy (55). 15N and 13Cmethyl relaxation dispersion experiments probe exchange dynamics between species with distinct chemical shifts on a timescale ranging from ∼100 μs to ∼10 ms. Experiments were acquired on U-[2H,15N]/Ile(δ1)-13CH3/Val,Leu-(13CH3/12C2H3)-labeled Alkbh5 at two different static fields (600 and 800 MHz) and three different temperatures (15, 20, and 25°C). Resonance assignment for the 1H-15N correlated spectra was performed based on the chemical shifts for the human Alkbh5 previously reported (25). 1H-13Cmethyl correlated spectra were assigned using out-and-back NMR experiments (28) on U-[2H,15N,13C] Ile(δ1)-(13CH3);Leu,Val-(13CH3/12CD3)]-labeled Alkbh5. The assigned chemical shifts are reported in Fig. S2.

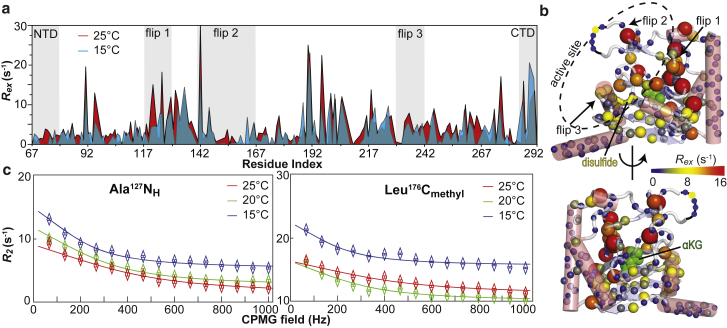

Large (>5 s−1) exchange contributions to the 15N and 13Cmethyl transverse relaxation rates (Rex) were detected for several residues in Alkbh5 (Fig. 4 a). The majority of the amino acids experiencing conformational exchange are located within or in the vicinity of the active site (Fig. 4 b). Interestingly, although the measured Rex values increase with increasing temperature throughout the protein sequence, the five C-terminal residues Leu287–Arg291 show the opposite trend, with Rex values decreasing with increasing temperature (Fig. 4 a). This finding suggests that the catalytic domain and the C-terminal region of Alkbh5 participate in two distinct conformational equilibria.

Figure 4.

μs-ms conformational dynamics in apo Alkbh5. (a) 800 MHz 15N and 13Cmethyl exchange contributions to the transverse relaxation rate (Rex) measured at 15 (blue) and 25 (red) °C are graphed versus residue index. 30% transparency was applied to the curve describing the Rex data at 15°C. (b) 800 MHz 15N and 13CmethylRex values measured at 25°C are plotted on the structure of apo Alkbh5 according to the color bar. Residues that are missing from the x-ray structure are indicated by a black curve. The Cys230–Cys267 disulfide bridge is shown as yellow sticks. αKG is modeled in the protein active site and shown as green spheres. (c) Examples of typical 800 MHz 15N (left) and 13Cmethyl (right) relaxation dispersion data at 15 (blue), 20 (green), and 25 (red) °C are shown. Data are shown for the Ala127-NH (left) and Leu176-Cmethyl resonances, with the experimental data represented by open diamonds and the best-fit curves for a two-site exchange model as solid lines. Similar plots for all the analyzed resonances are shown in Fig. S4 and S5. To see this figure in color, go online.

15N and 13Cmethyl relaxation dispersion curves of NMR peaks exhibiting Rex values >5 s−1 at 800 MHz and 25°C were fitted simultaneously to a model describing the interconversion of two conformational states (see Materials and Methods). In the global fitting procedure, the exchange rate (kex) and the fractional population of the minor state (pb) were optimized as global parameters, whereas the 15N and 13C chemical shift differences between the two conformational states (ΔωN and ΔωC, respectively) were treated as peak-specific parameters. Data acquired at multiple temperatures were fitted simultaneously, and ΔωN and ΔωC were treated as temperature-independent parameters. The two distinct conformational equilibria detected in the catalytic domain and at the C-terminal end of Alkbh5 are described by 24 and 4 relaxation dispersion profiles, respectively, and were analyzed separately. Results for both global fits are reported in Table 3. An example of the global fit for the equilibrium in the catalytic domain is provided in Fig. 4 c. Curves for all the 28 relaxation dispersions as well as the optimized ΔωN and ΔωC values are provided in Figs. S4 and S5 (for the catalytic domain and C-terminal equilibria, respectively). The overall exchange rate constants (sum of forward and backward rate constants, kab and kba, respectively) are 1130 ± 10, 1680 ± 15, and 2480 ± 20 s−1 at 15, 20, and 25°C, respectively, for the conformational equilibrium in the catalytic domain, and 800 ± 10, 1200 ± 15, and 1770 ± 25 s−1 at 15, 20, and 25°C, respectively, for the conformational equilibrium at the C-terminal end (Table 3). The populations of the minor species are 3.3 ± 0.3, 4.1 ± 0.5, and 4.8 ± 0.5% at 15, 20, and 25°C, respectively, for the conformational equilibrium in the catalytic domain, and 3.5 ± 0.2, 3.3 ± 0.2, and 3.2 ± 0.2% at 15, 20, and 25°C, respectively, for the conformational equilibrium at the C-terminal end (Table 3).

Table 3.

Kinetic and Thermodynamic Parameters for the μs-ms Conformational Exchange Processes Detected in the Catalytic Domain and C-Terminal Regions of apo Alkbh5

|

kab/kba (s−1)a |

Δ‡Habb |

Δ‡Sabb |

Δ‡Hbab |

Δ‡Sbab |

pb (%) |

ΔHc |

ΔSc |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15°C | 20°C | 25°C | kJ mol−1 | J K−1 mol−1 | kJ mol−1 | J K−1 mol−1 | 15°C | 20°C | 25°C | kJ mol−1 | J K−1 mol−1 |

| Catalytic domain conformational exchange | |||||||||||

| 37 ± 5 | 69 ± 9 | 119 ± 12 | 82 ± 9 |

71 ± 30 |

52 ± 1 |

−5 ± 3 |

3.3 ± 0.3 |

4.1 ± 0.5 |

4.8 ± 0.5 |

29 ± 10 |

72 ± 33 |

| 1092 ± 10 | 1611 ± 15 | 2361 ± 23 | |||||||||

| C-terminal conformational exchange | |||||||||||

| 28 ± 2 | 40 ± 3 | 57 ± 4 | 48 ± 1 | −52 ± 21 | 55 ± 1 | 1 ± 5 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | −7 ± 6 | −51 ± 21 |

| 772 ± 12 | 1160 ± 17 | 1713 ± 25 | NDd | ||||||||

The major and minor states of the equilibrium are referred to as a and b, respectively. kab and kba are the rate constants for the transition from a to b and from b to a, respectively, and are calculated from the values of the optimized parameters kex (= kab + kba) and pb. The upper and lower numbers refer to kab and kba, respectively.

Activation enthalpies and entropies for the a to b and b to a transitions were calculated by fitting the temperature dependence of kab and kba to the Eyring equation, respectively.

Enthalpy and entropy changes associated with the conformational equilibrium were calculated by using the van ’t Hoff equation. The equilibrium constant (Keq) at each temperature was calculated using the formula Keq = pb/(1 − pb).

ND, no data.

The temperature dependence of kab, kba, and pb was fitted using the van ’t Hoff and Eyring equations to obtain thermodynamic and kinetic information on the two conformational equilibria of Alkbh5. The obtained enthalpy (ΔH), entropy (ΔS), activation enthalpy (Δ‡H), and activation entropy (Δ‡S) are summarized in Table 3. Although the temperature range spanned by our relaxation dispersion experiments is quite limited and therefore the errors reported for the thermodynamic parameters are a lower-bound estimate, some general conclusions can be drawn about the Alkbh5 conformational equilibria. Indeed, the positive ΔS obtained for the equilibrium in the catalytic domain (72 J K−1 mol−1) suggests that the active site of apo Alkbh5 undergoes exchange between a highly populated conformation and a lowly populated state characterized by a higher degree of disorder. On the other hand, the negative ΔS associated with the conformational equilibrium at the C-terminal end (−51 J K−1 mol−1) indicates that these μs-ms dynamics describe transition to a lowly populated conformational state with decreased disorder. Modulation of these conformational equilibria by substrate/cofactor binding may contribute to the changes in conformational disorder observed for AlkB proteins upon ligand binding (18) and provide an important source of functional regulation for Alkbh5.

aMD/RDC refinement of apo Alkbh5 in solution

The results presented in the previous sections clearly indicate that the active site of apo Alkbh5 undergoes conformational dynamics on multiple timescales. Such conformational heterogeneity is not reproduced by the x-ray structure of the enzyme, as evidenced by the poor agreement between experimental and back-calculated RDC values (Fig. 1 a). To overcome the discrepancies between the x-ray structure and solution NMR data, we have developed a protocol that combines aMD and RDCs to generate a structural ensemble of Alkbh5 that satisfies the solution NMR data.

Dynamic conformational ensembles provide a more accurate description of flexible proteins than the traditional static structures obtained by x-ray crystallography (32, 56, 57). Currently, structural ensembles are generated using one of two major approaches. The first calculates the ensemble by simulated annealing driven by the experimental data. The second involves first generating a large pool of possible structures and then selecting from among these the most appropriate ensemble that fulfills the desired experimental observables (32, 56). In the latter case, it is important to generate a starting pool of structures that ensures maximal diversity and geometric feasibility of the conformers. Recently developed computational methods for advanced conformational sampling of proteins such as aMD simulations satisfy both requirements (24) and have been shown to generate structural ensembles that are compatible with solution NMR observables of small globular proteins (58).

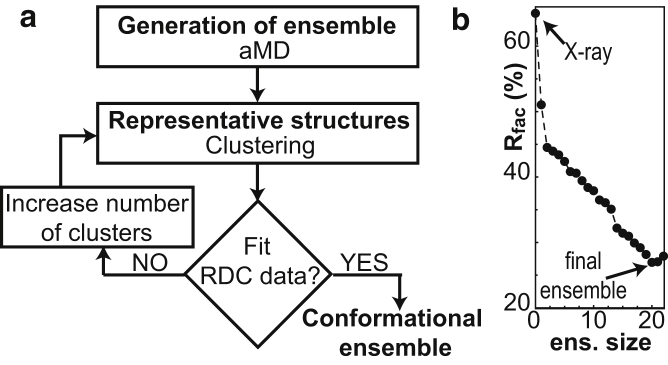

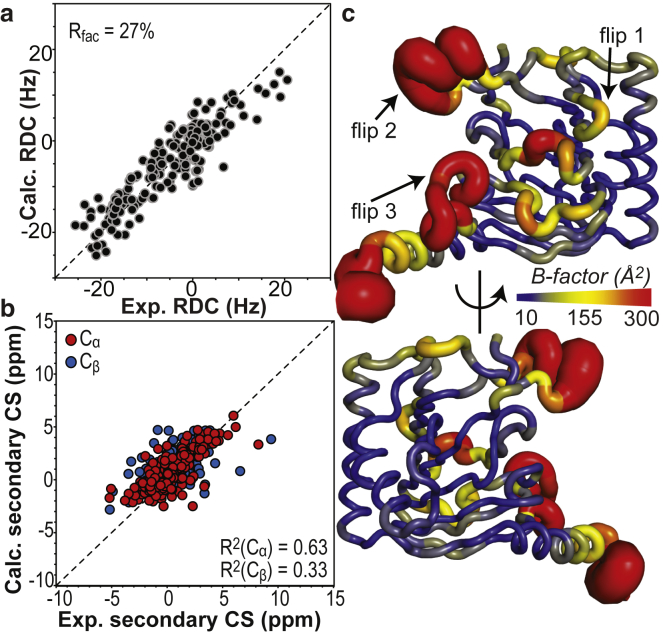

To generate a structural ensemble of Alkbh5, a 200 ns aMD simulation was run in Amber 16 starting from the x-ray structure of the apo enzyme (see Materials and Methods). Residues from flip 2 that are missing from the crystallographic structure (Leu145–Gly149, Fig. 2) were modeled using the software Modeler (44). Cys230 and Cys267 were simulated in the reduced state. The resulting trajectory was clustered to produce representative structures of the aMD with a high degree of structural diversity. Each representative structure was energy minimized, and the ensemble of representative structures was used to fit the experimental RDC data by optimizing the alignment tensor and population of each member of the ensemble (see Materials and Methods). The consistency between experimental and back-calculated RDC data was evaluated in terms of R-factor (32, 59). The protocol was iterated by increasing the number of clusters (and therefore the representative structures in the pool) until a stable R-factor was obtained (Fig. 5). Analysis of the R-factor as a function of the ensemble size indicates that a 20-member ensemble is needed to satisfy the experimental RDCs (Figs. 5 a and 6 a; Table 1). Of note, the generated ensemble is in better agreement than the x-ray structure with the Cα/Cβ secondary chemical shifts measured for apo Alkbh5 (the R2 values for linear regression of the Cα and Cβ secondary chemical shifts are 0.63 and 0.33, respectively; Fig. 6 b), which were not included in the conformer selection process.

Figure 5.

aMD/RDC refinement of protein conformational ensemble. (a) Schematic of the aMD/RDC ensemble calculation protocol developed in this work. A preliminary pool of structures is generated by aMD and subsequently filtered to maximize the agreement between experimental and back-calculated RDCs. The ensemble size (i.e., the number of conformers in the ensemble) is increased until the minimal R-factor is reached. (b) R-factor versus ensemble size for the aMD/RDC ensemble refinement of apo Alkbh5. A 20-member ensemble is required to fit the experimental RDCs.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the Alkbh5 structural ensemble with solution NMR data. (a) Agreement between the observed and back-calculated RDCs for the aMD/RDC refined ensemble of Alkbh5. Note that all the 188 experimental RDCs’ data were included in the calculation (see Table 1). (b) Agreement between measured and back-calculated Cα/Cβ secondary chemical shifts. Back-calculation of the NMR chemical shifts was done in Sparta+ (67). Predicted Cα/Cβ secondary chemical shifts are averaged over the aMD/RDC ensemble. R2 values for linear regression of the Cα and Cβ data are shown. (c) Sausage representation of the aMD/RDC ensemble generated using the software Pymol (70). Cartoons are colored according to the B-factor, as indicated by the color bar. B-factors were calculated using the formula , where Bi and Ui are the B-factor and mean-square displacement of atom i, respectively. The overlay of the 20 conformers in the ensemble is shown in Fig. S3. To see this figure in color, go online.

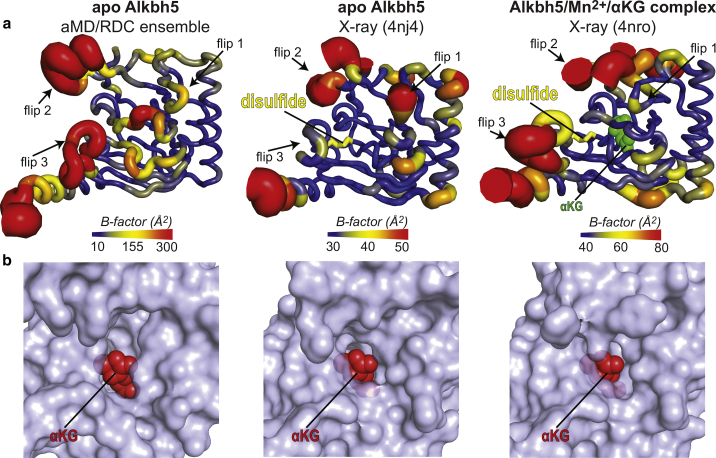

Although our data indicate that the overall fold of apo Alkbh5 in solution is unchanged relative to the crystal state, the dynamic picture of Alkbh5 provided by the conformational ensemble differs substantially from the one inferred by crystallography (Fig. 7 a). Indeed, the overall active site of apo Alkbh5 is more disordered in solution compared to the crystal state (note that the aMD/RDC ensemble has a much wider distribution of B-factor than the crystal structure, Fig. 7 a). In addition, the conformational ensemble reveals conformational dynamics at flip 3 and at the binding site for αKG that are not reported by the crystallographic B-factor (Fig. 7 a). Finally, although the aMD/RDC conformational ensemble shows that flip 1 (residues 117–129) is rigid in solution, analysis of the crystallographic B-factor suggests high degree of conformational disorder for this structural element in apo Alkbh5 (Fig. 7 a). The NMR relaxation data presented in Fig. 3 a show that the R2/R1 ratios for residues in flip 1 distribute close to the average value. This trend is typical of a rigid protein domain (54), therefore validating the ensemble model.

Figure 7.

Comparison between solution and crystal structures of human Alkbh5. (a) Sausage representations of the aMD/RDC ensemble (left), x-ray structure of apo Alkbh5 (center), and x-ray structure of Alkbh5 complexed with Mn2+ and αKG (right). Cartoons are colored according to the B-factor, as indicated by the color bar. B-factors for the aMD/RDC ensemble were calculated using the formula , where Bi and Ui are the B-factor and mean-square displacement of atom i, respectively. The Cys230–Cys267 disulfide bridge is shown as yellow sticks. αKG is shown as green spheres. (b) Close-up views of the αKG binding pocket in the aMD/RDC ensemble (left), x-ray structure of apo Alkbh5 (center), and x-ray structure of Alkbh5 complexed with Mn2+ and αKG (right). For the aMD/RDC ensemble, the conformer with the widest αKG binding pocket is displayed. One αKG molecule is modeled in the binding site of the apo protein (left and center panels). Alkbh5 is shown as a transparent light blue surface. αKG is shown as red spheres. To see this figure in color, go online.

As a final note, we should mention that the use of an electrostatic alignment medium makes determination of the alignment properties for each ensemble member based on molecular shape hard to achieve (32). Therefore, our approach required simultaneous optimization of the alignment tensor and of the fractional population for each ensemble member to minimize the difference between experimental and back-calculated RDCs (see Materials and Methods). In this case, the alignment tensor could absorb part of the conformational dynamics and, as a consequence, the conformational ensemble reported in Fig. 6 might be an underestimation on the conformational space sampled by Alkbh5. Blackledge and coworkers have developed an elegant approach to circumvent this limitation (60). However, this method requires acquisition of multiple sets of RDCs in multiple alignment media, which is not feasible for human Alkbh5.

Discussion

In this work, we describe a simple protocol to obtain protein conformational ensembles that satisfy experimental RDC data. The protocol consists in generation of a pool of diverse and geometrically feasible structures and subsequent reweighting of the generated pool using RDCs. To ensure maximal diversity in the structural pool, aMD was used to obtain an extensive sampling of conformational space, and clustering methods were employed to select a subset of diverse structures from the simulated trajectory. aMD and clustering algorithms are fully integrated in common MD simulation packages, such as Amber (42) and Gromacs (61). Back-calculation of RDCs from the conformational ensemble was done using well-established theory (see Materials and Methods) (32), and the MATLAB script to reweight the generated structural pool using RDC data that was developed here is available for download on our group webpage. Therefore, our protocol can be easily implemented by other research laboratories.

Using our aMD/RDC protocol, we have demonstrated that the human RNA demethylase Alkbh5 is more disordered than what is observed in the crystal structure of the enzyme. Such discrepancy is most likely due to the absence of the Cys230–Cys267 disulfide bridge in solution that limits the conformations accessible to flip 3 and to the αKG binding pocket in the crystal (Fig. 2). The aMD/RDC conformational ensemble obtained here reveals that the αKG binding pocket undergoes conformational dynamics that expand the active site (Fig. 7 b). Such breathing motions increase the solvent accessibility of the αKG binding pocket in apo Alkbh5 (Fig. 7 b) and might be essential to permit access of the small molecule substrate to the active site.

NMR relaxation experiments have confirmed the dynamic character of apo Alkbh5. Consistent with the aMD/RDC conformational ensemble, residues with low R2/R1 ratios were found predominantly at flip 2, the αKG binding pocket, and the terminal ends of the enzyme (Fig. 3), confirming that these regions have intrinsic flexibility. In addition, thermodynamic analysis of 15N and 13Cmethyl relaxation dispersion experiments acquired at multiple temperatures revealed that the active site and C-terminal end of Alkbh5 undergo two distinct conformational equilibria on the μs-ms timescale that further modulate the degree of structural disorder of Alkbh5 (Fig. 4; Table 3). Interestingly, disordered-to-ordered conformational changes were found to contribute to several stages of the catalytic cycle of AlkB dioxygenases (sequential substrate/cofactor binding, sequestration of a highly reactive intermediate species, and product release) (18, 19, 20), and an increasing body of literature indicates a regulatory role for structural heterogeneity and conformational disorder in several native enzymes (62, 63, 64, 65, 66). The set of experiments presented here allow a comprehensive characterization of the amplitude, kinetics, and thermodynamics of the conformational dynamics in Alkbh5, paving the way to future analyses on the role played by conformational dynamics in determining the activity and selectivity of the enzyme.

Author Contributions

J.A.P. and V.V. designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. J.A.P., T.T.N., T.K.E., R.R.D., B.K., and V.V. performed the research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Julien Roche for critical reading of the manuscript and the Protein Facility of the Iowa State University Office of Biotechnology for acquisition of all reported mass spectrometry data.

This work was supported by startup funding from Iowa State University (V.V.).

Editor: Monika Fuxreiter.

Footnotes

Five figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(18)31117-2.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Deng X., Su R., Chen J. Role of N6-methyladenosine modification in cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2018;48:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deng X., Su R., Chen J. RNA N6-methyladenosine modification in cancers: current status and perspectives. Cell Res. 2018;28:507–517. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0034-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esteller M., Pandolfi P.P. The epitranscriptome of noncoding RNAs in cancer. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:359–368. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng G., Dahl J.A., He C. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol. Cell. 2013;49:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantara W.A., Crain P.F., Agris P.F. The RNA modification database, RNAMDB: 2011 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D195–D201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toh J.D.W., Sun L., Woon E.C.Y. A strategy based on nucleotide specificity leads to a subfamily-selective and cell-active inhibitor of N6-methyladenosine demethylase FTO. Chem. Sci. (Camb.) 2015;6:112–122. doi: 10.1039/c4sc02554g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang T., Cheong A., Woon E.C. A methylation-switchable conformational probe for the sensitive and selective detection of RNA demethylase activity. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2016;52:6181–6184. doi: 10.1039/c6cc01045h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saneyoshi M., Harada F., Nishimura S. Isolation and characterization of N6-methyladenosine from Escherichia coli valine transfer RNA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1969;190:264–273. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(69)90078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei C., Gershowitz A., Moss B. N6, O2′-dimethyladenosine a novel methylated ribonucleoside next to the 5′ terminal of animal cell and virus mRNAs. Nature. 1975;257:251–253. doi: 10.1038/257251a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J., Yue Y., He C. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:93–95. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ping X.L., Sun B.F., Yang Y.G. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res. 2014;24:177–189. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X., Lu Z., He C. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2014;505:117–120. doi: 10.1038/nature12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jia G., Fu Y., He C. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:885–887. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer K.D., Patil D.P., Jaffrey S.R. 5′ UTR m(6)A promotes cap-independent translation. Cell. 2015;163:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y., Li Y., Zhao J.C. N6-methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:191–198. doi: 10.1038/ncb2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu R., Jiang D., Wang X. N (6)-methyladenosine (m(6)A) methylation in mRNA with A dynamic and reversible epigenetic modification. Mol. Biotechnol. 2016;58:450–459. doi: 10.1007/s12033-016-9947-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yue Y., Liu J., He C. RNA N6-methyladenosine methylation in post-transcriptional gene expression regulation. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1343–1355. doi: 10.1101/gad.262766.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ergel B., Gill M.L., Hunt J.F. Protein dynamics control the progression and efficiency of the catalytic reaction cycle of the Escherichia coli DNA-repair enzyme AlkB. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:29584–29601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.575647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu B., Edstrom W.C., Hunt J.F. Crystal structures of catalytic complexes of the oxidative DNA/RNA repair enzyme AlkB. Nature. 2006;439:879–884. doi: 10.1038/nature04561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bleijlevens B., Shivarattan T., Matthews S.J. Dynamic states of the DNA repair enzyme AlkB regulate product release. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:872–877. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aik W., Scotti J.S., McDonough M.A. Structure of human RNA N6-methyladenine demethylase ALKBH5 provides insights into its mechanisms of nucleic acid recognition and demethylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:4741–4754. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng C., Liu Y., Chen Z. Crystal structures of the human RNA demethylase Alkbh5 reveal basis for substrate recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:11571–11583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.546168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tjandra N., Bax A. Direct measurement of distances and angles in biomolecules by NMR in a dilute liquid crystalline medium. Science. 1997;278:1111–1114. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voter A.F. A method for accelerating the molecular dynamics simulation of infrequent events. J. Chem. Phys. 1997;106:4665. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purslow J.A., Venditti V. 1H, 15N, 13C backbone resonance assignment of human Alkbh5. Biomol. NMR Assign. 2018;12:297–301. doi: 10.1007/s12104-018-9826-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tugarinov V., Kanelis V., Kay L.E. Isotope labeling strategies for the study of high-molecular-weight proteins by solution NMR spectroscopy. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:749–754. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tugarinov V., Venditti V., Marius Clore G. A NMR experiment for simultaneous correlations of valine and leucine/isoleucine methyls with carbonyl chemical shifts in proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 2014;58:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10858-013-9803-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clore G.M., Starich M.R., Gronenborn A.M. Measurement of residual dipolar couplings of macromolecules aligned in the nematic phase of a colloidal suspension of rod-shaped viruses. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:10571–10572. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fitzkee N.C., Bax A. Facile measurement of 1H-15N residual dipolar couplings in larger perdeuterated proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 2010;48:65–70. doi: 10.1007/s10858-010-9441-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwieters C.D., Kuszewski J.J., Clore G.M. The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J. Magn. Reson. 2003;160:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venditti V., Egner T.K., Clore G.M. Hybrid approaches to structural characterization of conformational ensembles of complex macromolecular systems combining NMR residual dipolar couplings and solution X-ray scattering. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:6305–6322. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lakomek N.A., Ying J., Bax A. Measurement of 15N relaxation rates in perdeuterated proteins by TROSY-based methods. J. Biomol. NMR. 2012;53:209–221. doi: 10.1007/s10858-012-9626-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loria J.P., Rance M., Palmer A.G., III A TROSY CPMG sequence for characterizing chemical exchange in large proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 1999;15:151–155. doi: 10.1023/a:1008355631073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lundström P., Vallurupalli P., Kay L.E. A single-quantum methyl 13C-relaxation dispersion experiment with improved sensitivity. J. Biomol. NMR. 2007;38:79–88. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yip G.N., Zuiderweg E.R. A phase cycle scheme that significantly suppresses offset-dependent artifacts in the R2-CPMG 15N relaxation experiment. J. Magn. Reson. 2004;171:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mulder F.A., Skrynnikov N.R., Kay L.E. Measurement of slow (micros-ms) time scale dynamics in protein side chains by (15)N relaxation dispersion NMR spectroscopy: application to Asn and Gln residues in a cavity mutant of T4 lysozyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:967–975. doi: 10.1021/ja003447g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carver J.P., Richards R.E. A general two-site solution for the chemical exchange produced dependence of T2 upon the Carr-Purcell pulse separation. J. Magn. Reson. 1972;6:89–105. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Go Y.M., Jones D.P. Redox control systems in the nucleus: mechanisms and functions. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010;13:489–509. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sechi S., Chait B.T. Modification of cysteine residues by alkylation. A tool in peptide mapping and protein identification. Anal. Chem. 1998;70:5150–5158. doi: 10.1021/ac9806005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miao Y., Feher V.A., McCammon J.A. Gaussian accelerated molecular dynamics: unconstrained enhanced sampling and free energy calculation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:3584–3595. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Case D.A., Cheatham T.E., III, Woods R.J. The amber biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maier J.A., Martinez C., Simmerling C. ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:3696–3713. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eswar N., Webb B., Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling using Modeller. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics. 2006;Chapter 5:Unit-5.6. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0506s15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jorgensen W.L., Chandrasekhar J., Klein M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryckaert J.P., Ciccotti G., Berendsen H.J.C. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of N-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berendsen H.J.C., Postma J.P.M., Haak J.R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Essmann U., Perera L., Berkowitz M.L. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roe D.R., Cheatham T.E., III PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013;9:3084–3095. doi: 10.1021/ct400341p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shao J., Tanner S.W., Cheatham T.E. Clustering molecular dynamics trajectories: 1. characterizing the performance of different clustering algorithms. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2007;3:2312–2334. doi: 10.1021/ct700119m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pervushin K., Riek R., Wüthrich K. Attenuated T2 relaxation by mutual cancellation of dipole-dipole coupling and chemical shift anisotropy indicates an avenue to NMR structures of very large biological macromolecules in solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:12366–12371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bax A., Grishaev A. Weak alignment NMR: a hawk-eyed view of biomolecular structure. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2005;15:563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu C., Liu K., Min J. Structures of human ALKBH5 demethylase reveal a unique binding mode for specific single-stranded N6-methyladenosine RNA demethylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:17299–17311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.550350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kay L.E., Torchia D.A., Bax A. Backbone dynamics of proteins as studied by 15N inverse detected heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy: application to staphylococcal nuclease. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8972–8979. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mittermaier A., Kay L.E. New tools provide new insights in NMR studies of protein dynamics. Science. 2006;312:224–228. doi: 10.1126/science.1124964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ángyán A.F., Gáspári Z. Ensemble-based interpretations of NMR structural data to describe protein internal dynamics. Molecules. 2013;18:10548–10567. doi: 10.3390/molecules180910548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Venditti V., Schwieters C.D., Clore G.M. Dynamic equilibrium between closed and partially closed states of the bacterial Enzyme I unveiled by solution NMR and X-ray scattering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:11565–11570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515366112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Markwick P.R., Bouvignies G., Blackledge M. Exploring multiple timescale motions in protein GB3 using accelerated molecular dynamics and NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4724–4730. doi: 10.1021/ja0687668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clore G.M., Garrett D.S. R-factor, free R, and complete crossvalidation for dipolar coupling refinement of NMR structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:9008–9012. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salmon L., Blackledge M. Investigating protein conformational energy landscapes and atomic resolution dynamics from NMR dipolar couplings: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2015;78:126601. doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/78/12/126601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van Der Spoel D., Lindahl E., Berendsen H.J. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palombo M., Bonucci A., Zambelli B. The relationship between folding and activity in UreG, an intrinsically disordered enzyme. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:5977. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06330-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Larion M., Miller B., Brüschweiler R. Conformational heterogeneity and intrinsic disorder in enzyme regulation: glucokinase as a case study. Intrinsically Disord. Proteins. 2015;3:e1011008. doi: 10.1080/21690707.2015.1011008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DeForte S., Uversky V.N. Not an exception to the rule: the functional significance of intrinsically disordered protein regions in enzymes. Mol. Biosyst. 2017;13:463–469. doi: 10.1039/c6mb00741d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Venditti V., Tugarinov V., Clore G.M. Large interdomain rearrangement triggered by suppression of micro- to millisecond dynamics in bacterial Enzyme I. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:5960. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zotter A., Bodor A., Ovádi J. Disordered TPPP/p25 binds GTP and displays Mg2+-dependent GTPase activity. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:803–808. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shen Y., Bax A. SPARTA+: a modest improvement in empirical NMR chemical shift prediction by means of an artificial neural network. J. Biomol. NMR. 2010;48:13–22. doi: 10.1007/s10858-010-9433-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koradi R., Billeter M., Wuthrich K. MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:51–55, 29–32. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shen Y., Delaglio F., Bax A. TALOS+: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J. Biomol. NMR. 2009;44:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.DeLano W.L. Schrödinger, LLC; New York: 2002. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.