Abstract

We have developed a new approach, to our knowledge, to quantify the equilibrium exchange kinetics of carrier-mediated transmembrane transport of fluorinated substrates. The method is based on adapted kinetic theory that describes the concentration dependence of the transmembrane exchange rates of two competing, simultaneously transported species. Using the new approach, we quantified the kinetics of membrane transport of both anomers of three monofluorinated glucose analogs in human erythrocytes (red blood cells) using 19F NMR exchange spectroscopy. An inosine-based glucose-free medium was shown to promote survival and stable metabolism of red blood cells over the duration of the experiments (several hours). Earlier NMR studies only yielded the apparent rate constants and transmembrane fluxes of the anomeric species, whereas we could categorize the two anomers in terms of the catalytic activity (specificity constants) of the glucose transport protein GLUT1 toward them. Differences in the membrane permeability of the three glucose analogs were qualitatively interpreted in terms of local perturbations in the bonding of substrates to key amino acid residues in the active site of GLUT1. The methodology of this work will be applicable to studies of other carrier-mediated membrane transport processes, especially those with competition between simultaneously transported species. The GLUT1-specific results can be applied to the design of probes of glucose transport or inhibitors of glucose metabolism in cells, including those exhibiting the Warburg effect.

Introduction

Glucose transport via GLUT proteins

D-Glucose (Glc) metabolism is essential to all living systems (1). Because of the marked hydrophilicity of Glc, lipid bilayer membranes impose a significant barrier to its exchange into and out of cells. Consequently, most organisms have evolved specialized membrane proteins that catalyze this process (2). In humans, the GLUT family of integral membrane proteins, consisting of 14 known isoforms (3, 4), perform this function. Of these, GLUT1 (UniProt Accession ID: P11166) is the most abundant and, of relevance to this work, is the major glucose transporter in the human erythrocyte (red blood cell; RBC), where it is essential for cell viability (5).

GLUT1 and some other GLUT isoforms are overexpressed in cancer cells, and this correlates with the increased demand for Glc that defines the Warburg effect (6, 7). This makes members of this class of proteins appealing as therapeutic drug targets (8, 9), so there is a considerable interest in the development of novel compounds that bind to and inhibit GLUT1 (10, 11). To improve the molecular recognition of drug candidates by GLUT proteins, various means of incorporating Glc into larger molecules or mimicking the Glc scaffold are being actively explored (12).

The crystal structure of GLUT1 was reported by Deng et al. in 2014 (13). The crystallized protein had n-nonyl-β-D-glucopyranoside in the binding pocket, which allowed the transporter to be captured in the inward-open conformation. In 2015, the same group reported a high-resolution structure of GLUT3 complexed with Glc in an outward-occluded conformation (14). Two additional crystal structures of GLUT3 with the exofacial inhibitor maltose, captured in outward-open and outward-occluded conformations, were also reported (14). These developments enabled a schematic interpretation of the molecular recognition forces that govern binding and transport of Glc by the GLUTs. On the other hand, there have been few quantitative results that describe these proteins “in action” (in real time) as they bind and discharge their substrates, thus mediating transmembrane Glc flux.

F-substituted glucoses as substrates

A fluorine atom can serve as a hydrogen-bond acceptor, but unlike an −OH group, it cannot be a hydrogen-bond donor (15). Therefore, systematic substitutions of −OH groups by H or F atoms in carbohydrates can be used to probe the participation of specific −OH groups in the binding of carbohydrates to enzymes (16, 17, 18). Several fluoro-deoxy-glucoses (FDGs) have been assessed as GLUT1 substrates using 19F NMR spectroscopy (19, 20, 21, 22). However, only apparent rate constants for transport using a single substrate concentration were estimated, without taking into account Michaelis-Menten kinetics and substrate saturation effects. In this work, we adapted a previously developed kinetic theory based on the “single-site alternating-access” model and studied the transport of monofluorinated glucoses in human RBCs with a range of different substrate concentrations. This allowed interpretation of the results in terms of the specificity constants of GLUT1 toward these fluorosugars as it operates in situ, in the membranes of fully viable RBCs.

Materials and Methods

Materials

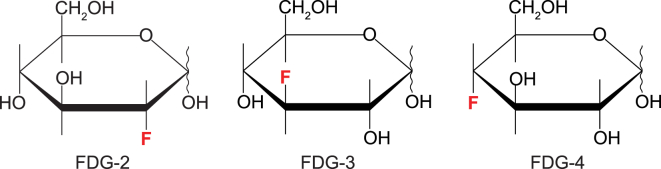

The three studied monofluoro-deoxy-D-glucoses (Fig. 1) were obtained from Carbosynth (Compton, UK). Stock solutions were prepared in deuterated saline (154 mM NaCl in D2O). The 99% pure D2O was from the Australian Institute of Nuclear Science and Engineering (Lucas Heights, Australia).

Figure 1.

The three studied monofluorinated glucose analogs. To see this figure in color, go online.

The “inosine saline” medium used for RBC suspensions (300 mOsm kg−1 (pH 7.4)) consisted of 10 mM inosine, 10 mM sodium pyruvate, 5 mM NaH2PO4, 4.5 mM NaOH, 10 mM KCl, and 133 mM NaCl in Milli-Q H2O. The osmolality of the saline solutions was measured with a vapor-pressure osmometer (model 5520; Wescor Instruments, Logan, UT). All stock saline solutions were isotonic with RBCs. The solutions were passed three times through a cellulose acetate filter with a pore size of 0.2 μm (Millipore, Burlington, MA) and stored at 4°C.

Cytochalasin B was purchased from Sapphire Bioscience (Redfern, Australia). Its 20 mM stock solution was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide-d6, and typically 2.5 μL of this solution was added to 0.5 mL of an NMR sample in GLUT1 inhibition studies; this led to a final concentration of 0.1 mM. All other fine chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO).

RBC sample preparation

Fresh blood samples were taken from a single donor by cubital fossa venipuncture (informed consent was obtained from the subject, and approval was given by The University of Sydney Human Ethics Committee). Heparin was used as an anticoagulant at a concentration of 15 IU (mL blood)−1 (23). Each blood sample (∼20 mL) was centrifuged at 3000 × g for 5 min at 10°C, which allowed the separation of RBCs by vacuum-pump aspiration of the blood plasma and buffy coat.

The RBCs were washed twice in saline (154 mM NaCl in Milli-Q H2O) and then twice in inosine saline. Washing involved resuspending the cells in ∼5 volumes of the washing medium, centrifuging at 3000 × g for 5 min at 10°C, and removing the supernatant by vacuum-pump aspiration. Before the last washing step with saline, the cells were bubbled with carbon monoxide for 10 min to convert the RBC hemoglobin into its stable diamagnetic form for optimal resolution and signal/noise in the subsequent NMR spectra.

The obtained RBC suspensions were mixed with various amounts of fluorosugars in 5-mm NMR tubes. In all 19F NMR experiments, the final volume of the sample in an NMR tube (Vtot) was 0.5 mL, which had 10% (v/v) D2O and hematocrit (Ht) = 60–70%. In each individual case, the Ht value was measured using a capillary centrifuge (Clements, North Ryde, Australia) and taken into account when calculating the total aqueous volume of the sample (Eq. S1). All molar substrate concentrations in the NMR samples were calculated with respect to the total aqueous volume of the sample (Vaq) rather than the total volume of the RBC suspension in the NMR tube (Vtot).

Light microscopy

The microscope images were acquired using a 100× objective on an Olympus BX51 light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) using the DIC mode. Image analysis was done using Olympus software.

NMR spectroscopy

General

All NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Avance III 400 spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin, Karlsruhe, Germany) using either 5-mm dual 19F/1H or 10-mm broadband observe gradient probes (Bruker). 10% (v/v) D2O was used for locking the spectrometer’s magnetic field. In all NMR experiments, the sample temperature was 37°C, which was calibrated using a standard sample of neat methanol-d4. Spectra were recorded and processed using Bruker TopSpin 3.5 software.

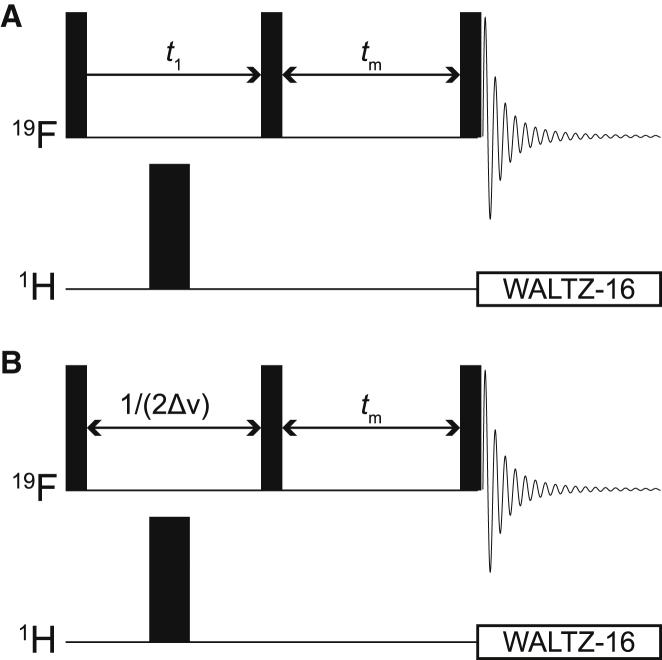

2D EXSY

The pulse sequence used for the two-dimensional (2D) exchange spectroscopy (EXSY) experiments is shown in Fig. 2 A. 1H decoupling during the direct and indirect acquisition periods was achieved with WALTZ-16 composite-pulse decoupling (24) (90° decoupler-pulse duration of 90 μs centered at 4 ppm) and a high-power 180° 1H pulse, respectively. Two transients were accumulated per free induction decay (FID) to suppress axial peaks by a two-step phase cycle of the first 90° pulse (viz., x, −x; acquire: x, −x) (25). The intertransient delay was 1 s, and the mixing time tm was set to 0.5 s. The acquired data matrix consisted of 256 and 32 complex points in the direct and indirect acquisition dimensions, respectively. The spectral width varied from 3 to 6 ppm depending on the chemical shift dispersion of 19F NMR signals of individual sugars. Spectra were processed with a cosine-squared window multiplication function in both frequency dimensions, and the data were extended to 128 complex points in the indirect acquisition dimension by the standard linear prediction algorithm in TopSpin.

Figure 2.

NMR pulse sequences used in this study: (A) 19F 2D EXSY with 1H decoupling in the two dimensions; (B) 19F 1D EXSY: the incremented period (t1) is replaced by a fixed delay 1/(2Δν), where Δν is the difference in chemical shift between the resonances (in Hz) of the two exchanging populations. Horizontal lines labeled “1H” and “19F” represent separate radio frequency channels tuned to the resonance frequency of 1H and 19F, respectively. Narrow and wider black rectangles represent 90° and 180° hard radio frequency pulses, respectively, applied at the frequency of the corresponding channel. The decaying oscillating curve denotes signal (FID) acquisition, and the open rectangles represent WALTZ-16 composite pulse decoupling (24).

1D EXSY

The pulse sequence used for the one-dimensional (1D) EXSY experiments is shown in Fig. 2 B. Four or eight transients were acquired per FID (the larger number was used for lower concentrations of FDGs), and a four-step phase cycle of the last 90° pulse was used to select the zero-order spin coherence during the mixing time (x, y, −x, −y; acquire: x, y, −x, −y). Each FID was recorded using 4096 complex points with a spectral width of 35.9 ppm and an acquisition time of 0.3 s. The radio frequency transmitter was set “on resonance” with the intracellular spin population to achieve the selective inversion of its magnetization at the beginning of the experiment. The longitudinal relaxation time constants (T1) were estimated from an inversion-recovery experiment; in all cases, the values were less than 1.5 s; therefore, an intertransient delay of 8 s (>5 T1 values) was used to yield spectra that were suitable for quantitative kinetic analysis. Spectra were processed with exponential line broadening of 3 Hz, zero filled to 32,768 complex points and phase corrected in TopSpin. Acquisition and processing of spectra was repeated for 16 different mixing times ranging from 0 to 5 s (0, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, 0.25, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, and 5.0 s) and with five different substrate concentrations (6.2, 9.3, 12.4, 18.6, and 24.8 mM).

1H spin-echo

1H spin-echo NMR spectra of RBCs in various media were recorded for 5 min (using spin-echo delay τ = 67 ms) in 1-h intervals using the experiment described in (26). 128 transients were recorded with an intertransient delay of 2 s per spectrum. Each FID was acquired using 1024 complex points, a spectral width of 10 ppm, and an acquisition time of 0.256 s. The water resonance was suppressed by using presaturation during the intertransient delay.

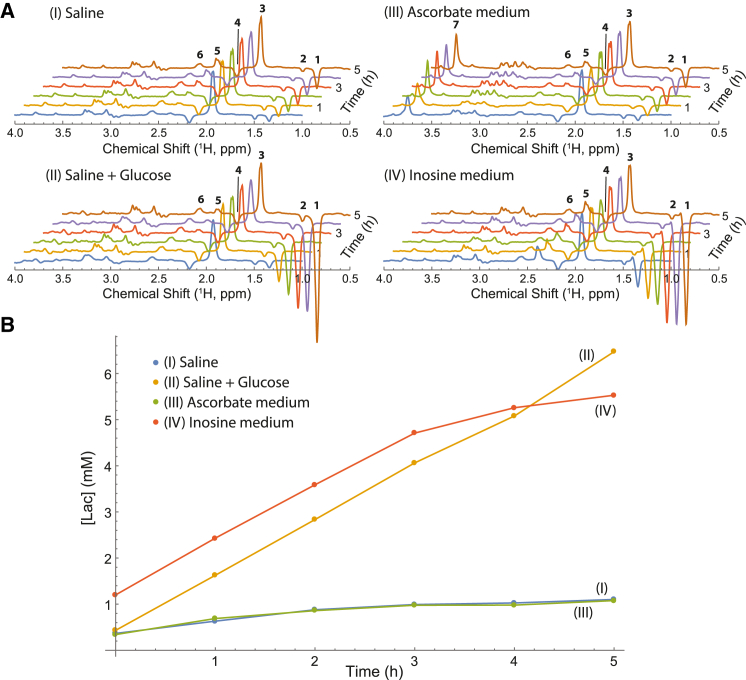

Six spectral time points were acquired for each of the samples in experiments conducted for 5 h. To quantify the lactate production rates, an internal standard of a nonmetabolized inert compound (5 mM acetate) was added to each sample (peak 3 in Fig. 3 A). Also, a separate sample with known quantities of acetate (5 mM) and lactate (10 mM) was used to acquire a 1H spin-echo NMR spectrum under the same experimental conditions. This allowed us to calculate the coefficients of proportionality, which are required for the conversion of the measured lactate peak intensities to the corresponding concentrations in mM.

Figure 3.

Lactate production by RBCs in four suspension media. (A) 400.13 MHz 1H NMR spin-echo spectral time courses of RBC suspensions in the four studied media (see text). The following assignments were made by adding individual substances to the samples in a separate experiment and using previously published data (78): 1 (1.34 ppm), CH3 of lactate; 2 (1.49 ppm), CH3 of alanine and/or pyruvate hydrate; 3 (1.93 ppm), CH3 of acetate; 4 (2.18 ppm), CH2(β) of the glutamyl residue in reduced glutathione; 5 (2.39 ppm), CH3 of pyruvate (keto-form); 6 (2.57 ppm), CH2(γ) of the glutamyl residue in reduced glutathione; 7 (3.74 ppm), CH2 of Tris buffer. The spectra were scaled so that the intensities of the acetate peaks were the same in each series. (B) Production of lactate by RBCs, as calculated from the spectra of (A), over the duration of the experiment (5 h at 37°C). Coefficients of variation in concentration estimates were uniformly less than 5%. To see this figure in color, go online.

Computation and statistical analysis

1D EXSY spectra were imported into Mathematica (Wolfram, Champaign, IL) (27), in which peak integration and subsequent numerical data analysis were performed. The integrals of the two NMR signals were measured at each mixing time; this generated time-course plots for the two exchanging magnetizations as functions of the mixing time, viz., Me(tm) and Mi(tm). The model of Eqs. 1 and 2 was fitted to the obtained time courses using Mathematica’s routine “NonlinearModelFit” with a Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm, which allowed estimation of the exchange-rate constants with their corresponding standard errors. Selective inversion of the intracellular NMR signal specified a key initial condition for the solution of Eqs. 1 and 2: and .

Lactate production rates were quantified for the initial linear period of the reaction (0–3 h) by fitting a straight line to the experimental data using Mathematica’s routine “LinearModelFit.” For testing the statistical significance of the difference between the slopes of any two lines, the standard two-tailed t-test was used.

Results

Stability of RBCs in inosine medium

Accurate membrane transport studies of GLUT1 require that the RBCs are maintained in a stable morphological and metabolic state in a glucose-free medium before the experiments (and then in the presence of the glucose analogs during the experiment). Therefore, given the prolonged incubations (up to 3 h) used for many of the experiments, we first aimed to establish and verify an optimal glucose-free medium, which was composed to prolong the integrity of metabolically active human RBCs during the fluorosugar 19F NMR EXSY experiments.

To provide a non-glucose-based energy source, which is required for RBC survival over several hours, an inosine-based saline with additional pyruvate, phosphate, and KCl was employed. Pyruvate, as the oxidized counterpart of lactate in the lactate dehydrogenase (E.C. 1.1.1.27) reaction, helps to maintain a higher concentration of NADH, which promotes flux through the second half of glycolysis, starting with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (E.C. 1.2.1.12), and reduces spontaneous oxidation reactions. KCl provides the extracellular cation for continual activity of Na+,K+-ATPase, the dominant site of ATP hydrolysis in the cell and therefore a major determinant of glycolytic flux.

To assess the stability of RBCs in the medium, we used 1H spin-echo NMR experiments (26) to monitor ongoing production of lactate from glycolysis by RBCs in four different media: (I) “normal” saline (150 mM NaCl + 10 mM KCl); (II) “normal” saline with addition of 10 mM Glc; (III) the “standard” ascorbate saline that was used in some previous 19F NMR studies of fluorosugars with RBCs (21, 28, 29); and (IV) the developed inosine saline. The obtained 1H spin-echo NMR spectra are shown as stack plots in Fig. 3 A.

Each of the samples showed ongoing production of lactate (as a steady growth of peak 1 in Fig. 3 A). Fig. 3 B shows the increase in lactate concentration over time in the samples in the four different media. The rate of lactate production was significantly greater in the samples containing an energy-supply substrate (glucose (II) and inosine (IV)), in comparison with the substrate-free samples (“normal” saline (I) and the ascorbate medium (III)) (Fig. 3). We ascribed the production of lactate in samples (I) and (III) to the breakdown of endogenous 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate.

There was no statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) in lactate production rates between sample (II) (1.74 ± 0.03 mmol (L RBC)−1 h−1) and sample (IV) (1.71 ± 0.03 mmol (L RBC)−1 h−1), indicating that the glycolytic rate in the inosine-based saline was the same as for the glucose-supplied control. In contrast, samples (I) and (III) did not have any energy-supply substrate, and this clearly led to “metabolic starvation” of the cells.

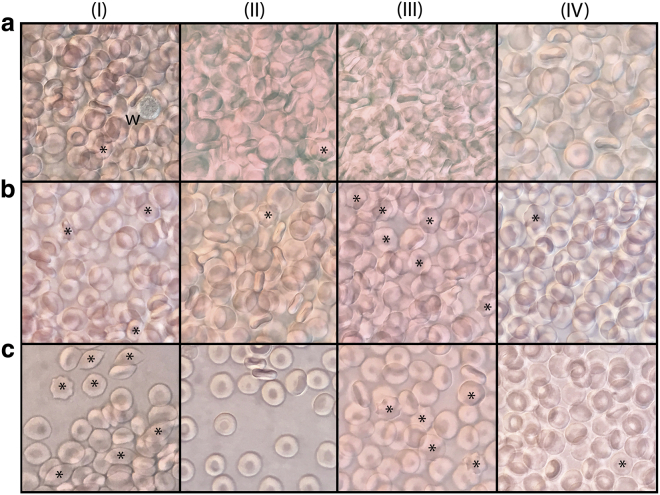

The samples used for the 1H spin-echo experiments were also examined with DIC light microscopy. Digital micrographs of each of the samples (in media I–IV) were recorded immediately before the NMR measurements and after 3 and 5 h of incubation at 37°C; representative micrographs are shown in Fig. 4. The images confirmed the integrity (biconcave disk shape) of the RBCs in the glucose and inosine media. This indicated that the RBCs survived well and were not adversely affected by any of the solutes and ions in the inosine-saline solution, making it a suitable glucose-free medium for the cells. In contrast, there was a notable formation of RBCs with irregular shapes (early echinocytes) in the samples that did not have energy-supply substrates (these cells are marked with asterisks in Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

DIC light micrographs of RBCs in samples (in media I–IV) used in the experiment of Fig. 3. The micrographs for each sample were obtained (a) before the acquisition of the 1H spin-echo spectra and (b) upon 3 h and (c) upon 5 h after the start of the incubation at 37°C. The asterisks indicate the most obvious cells of irregular shape, and “w” labels a white blood cell in micrograph (aI). To see this figure in color, go online.

Overall, the results indicated that the RBCs were metabolically stable in inosine saline for at least 3 h at 37°C. This was sufficient for the readily scheduled acquisition of a series of 19F NMR EXSY experiments.

1D 19F NMR experiments

Initially, we measured 1D 19F NMR spectra of each of the studied fluorosugars added to a suspension of RBCs (Figs. S1–S3). The peaks from both anomers present inside and outside the RBCs were clearly visible, and they were assigned using previous reports (20, 21). The mutarotation constant Kmut = [β]/[α] and anomeric ratio a (Eq. 9) of the three sugars inside and outside the cells were readily measured from the ratio of the peak integrals, and it was verified that ainside and aoutside were equal in all cases (within a ∼3% margin of error). The values of the anomeric ratios a for each of the three fluorosugars are given in the first column of Table 2. Measurement of 1D spectra was repeated after incubation of the samples for ∼3 h at 37°C. No new resonances were observed in the spectra, indicating that phosphorylation and further metabolism of the fluorinated glucose analogs were slow under the particular experimental conditions used.

Table 2.

Values of the Michaelis-Menten Parameters of GLUT1 for the Studied Fluorinated Sugars at 37°C

| aa | K′m, mMb | k′cat, s−1b | kcat/Km, 105 × M−1 s−1c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDG-2α | 0.45 ± 0.02 | 10.5 ± 1.6 | 4490 ± 350 | 9.5 ± 1.7 |

| FDG-2β | 4150 ± 330 | 7.2 ± 1.3 | ||

| FDG-3α | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 4.6 ± 0.9 | 4490 ± 290 | 21.2 ± 4.4 |

| FDG-3β | 3730 ± 250 | 15.0 ± 3.1 | ||

| FDG-4α | 0.42 ± 0.02 | 18.5 ± 1.3 | 5430 ± 240 | 6.9 ± 0.6 |

| FDG-4β | 1820 ± 90 | 1.7 ± 0.2 |

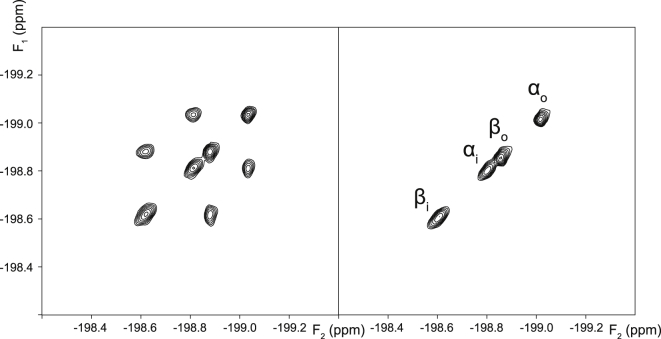

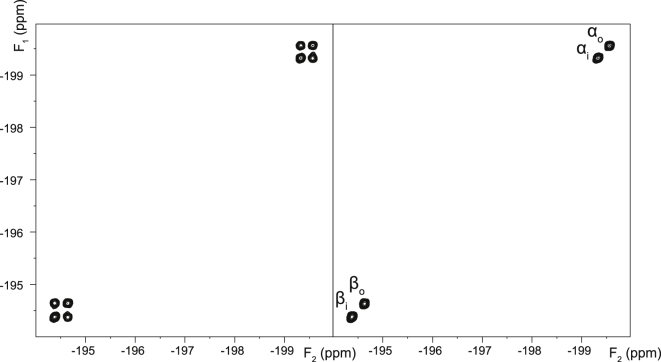

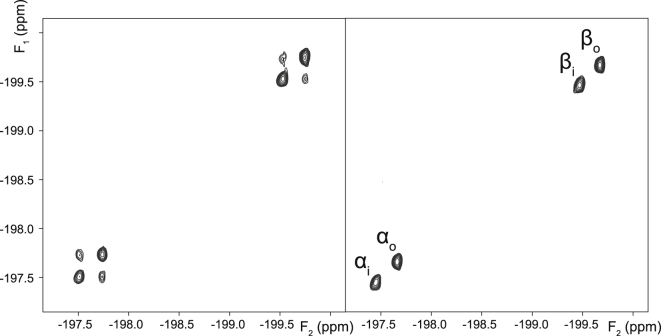

2D EXSY experiments

2D EXSY 19F NMR spectra were recorded from the three studied monofluorinated analogs of Glc in RBC suspensions. These spectra showed no crosspeaks between the spin populations of the α- and β-anomers (Figs. 5, 6, and 7 for FDG-2, FDG-3, and FDG-4, respectively), as observed by O’Connell et al. (21). Importantly, this indicated that the anomeric exchange (mutarotation) was negligible on the timescale of the EXSY mixing time (0.5 s) and could safely be ignored in the subsequent kinetic analysis. By contrast, for each anomer, there were prominent crosspeaks between the resonances of the corresponding extracellular and intracellular spin populations (Figs. 5, 6, and 7), reflecting the extent of their transmembrane exchange.

Figure 5.

2D EXSY 19F NMR spectra (376.46 MHz) of 12.4 mM FDG-2 in an RBC suspension in the absence (left panel), and presence of 0.1 mM cytochalasin B (right panel). The spectra were recorded with the pulse sequence shown in Fig. 2A, using a mixing time tm = 0.5 s. The subscripts “o” and “i” denote extracellular and intracellular populations of the α and β anomers, respectively.

Figure 6.

2D EXSY 19F NMR spectra (376.46 MHz) of 12.4 mM FDG-3 in an RBC suspension in the absence (left panel), and presence of 0.1 mM cytochalasin B (right panel). The spectra were recorded with the pulse sequence shown in Fig. 2A, using a mixing time tm = 0.5 s.

Figure 7.

2D EXSY 19F NMR spectra (376.46 MHz) of 6.2 mM FDG-4 in an RBC suspension in the absence (left panel), and presence of 0.1 mM cytochalasin B (right panel). The spectra were recorded with the pulse sequence shown in Fig. 2A, using a mixing time tm = 0.5 s.

In a control experiment, it was verified that the exchange crosspeaks completely disappeared in the presence of 0.1 mM cytochalasin B, a known inhibitor of glucose transport in human RBCs (30), as shown in Figs. 5, 6, and 7. This was consistent with transmembrane exchange of the FDGs being mediated by GLUT1, whereas the contribution of passive permeation by diffusion was negligible (in the mixing time of the EXSY experiment).

Determination of exchange rates constants

To measure the rate constants for influx (kei) and efflux (kie), the 1D counterpart of the 2D EXSY experiment (31) was used. It allowed more precise measurements in a shorter experiment time. From Figs. 5, 6, and 7, it is clear that, for a given fluorinated sugar, there are two independent pairs of exchanging spin populations. Thus, the rates of magnetization exchange of each anomer can be described by a pair of simultaneous two-site Bloch-McConnell differential equations (32). In the context of the 1D EXSY experiment, the time dependence of longitudinal magnetization of the extracellular Me(t) and intracellular Mi(t) spin populations during the mixing time tm is given by the following:

| (1) |

and

| (2) |

where and are the longitudinal relaxation-rate constants characterizing the return of the longitudinal magnetizations to the corresponding thermal equilibrium values, and . kei and kie are the rate constants for influx and efflux, respectively, as defined by Eqs. S4–S6.

Solution of the Bloch-McConnell differential equations gives the dependence of the intensities of the NMR signals in a magnetization-transfer experiment on the mixing time (33). Fitting the numerical solutions of Eqs. 1 and 2 to the experimental dependencies of Me and Mi on the mixing time yielded estimates of the rate constants kei and kie for both anomers together with their standard errors. As described in the Supporting Materials and Methods, it is more convenient to work with the efflux rate constant kie rather than the influx rate constant kei because the former is not dependent on the hematocrit value (21). Because of the variable extent of saturation of GLUT1 with substrate molecules, the exchange rate constants are functions of substrate concentration. Examples of 1D EXSY spectra and fitted curves are shown in Figs. S4–S9, and the statistically estimated kie values are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Values of the Apparent Efflux Rate Constant kie, s−1, at Different Substrate Concentrations

| Total Substrate Concentration [S] ([α] + [β]) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.2 mM | 9.3 mM | 12.4 mM | 18.6 mM | 24.8 mM | |

| FDG-2αa | 1.44 ± 0.21 | 1.25 ± 0.11 | 1.02 ± 0.14 | 0.91 ± 0.06 | 0.67 ± 0.07 |

| FDG-2βa | 1.36 ± 0.24 | 1.17 ± 0.15 | 0.95 ± 0.11 | 0.81 ± 0.03 | 0.58 ± 0.09 |

| FDG-3αa | 2.21 ± 0.21 | 1.76 ± 0.05 | 1.54 ± 0.07 | 0.98 ± 0.06 | 0.92 ± 0.03 |

| FDG-3βa | 1.88 ± 0.09 | 1.49 ± 0.06 | 1.21 ± 0.03 | 0.80 ± 0.03 | 0.74 ± 0.02 |

| FDG-4αa | 1.18 ± 0.13 | 1.07 ± 0.08 | 0.91 ± 0.06 | 0.80 ± 0.04 | 0.68 ± 0.02 |

| FDG-4βa | 0.40 ± 0.10 | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.02 |

| Glc-αb | 1.20 ± 0.40 | ||||

| Glc-βb | 0.71 ± 0.30 | ||||

Statistically estimated values that were obtained (along with their standard errors) from the fitting of the numerical solutions of the Bloch-McConnell equations (Eqs. 1 and 2) to the peak intensities of the 19F NMR 1D EXSY experiments conducted at 37°C.

Data, as reported in (61), obtained by using 13C NMR spin transfer experiments at 40°C for a total glucose concentration of 25.5 mM.

Next, we used the values of kie for the calculation of the equilibrium exchange rate υ of each anomer (by combining Eq. S4 with Eq. S14):

| (3) |

where is the mole quantity of the substrate in the intracellular compartment at equilibrium and Vaq is the total aqueous volume of the sample. It is convenient to normalize the transport rate υ with respect to the total concentration of the carrier, [C], and substrate in the sample. This leads to the following expression:

| (4) |

where c is the total mole quantity of the active carrier (monomers, although possibly operating as a higher oligomer) in the sample; χC is the number of copies of the carrier per cell (∼200,000 for GLUT1 (34)); NRBC is the total number of cells in the sample; Vi is the total intracellular volume of the sample accessible to solutes; VRBC is the average physical volume of one RBC (86 fL in isotonic solution (23)); faq = 0.717 is the fraction of the intracellular volume that is aqueous (35); and NA = 6.02214 × 1023 mol−1 is Avogadro’s number. From Eq. 4, it is evident that the normalized transport rate is directly proportional to the efflux rate constant kie and is independent of Ht. Nevertheless, because of the saturability of the carrier by substrate, the exchange rate constants kei and kie (and transport rates υ) are nonlinear functions of the respective anomer concentrations (Table 1).

Determination of the catalytic activity of GLUT1 on individual anomers

The equilibrium exchange kinetics of GLUT1-mediated transport can be described by the Michaelis-Menten steady-state enzyme kinetic equation that has been extended to account for competing substrates (see Supporting Materials and Methods). The kinetics of glucose transport in erythrocytes has been studied for at least 50 years. Nevertheless, despite the abundance of experimental data on this topic, there is still controversy surrounding the mechanism of glucose transport by GLUT1. The two main theories that have been proposed to account for the available kinetic data are the “simple carrier” and the “fixed-site carrier” models (36). The former model assumes that the protein’s binding site at any given instant can either be exposed to the inside or the outside of the cell membrane, whereas the latter model assumes that both binding sites can be occupied by substrate molecules at the same time. In 1968, Miller performed a wide range of kinetic experiments (37) and concluded that none of the existing theories were able to fully describe the obtained data (38). In the 1990s, Naftalin and Rift’s study of rat erythrocytes rejected the simple-carrier model in favor of the fixed-site carrier (39); however, based on later studies of human RBCs, Carruthers et al. concluded that neither model of transport is consistent with the available experimental data (36). Nevertheless, the recently determined crystal structures of GLUTs with bound substrates provide strong supporting evidence for the “simple carrier” model (14). Therefore, we modeled the overall reaction scheme for transmembrane exchange of the two anomeric species using a kinetic scheme based on the simple carrier model (Fig. S12). The Supporting Materials and Methods describe the details of our derivation, which allowed us to develop the equations for equilibrium exchange kinetics in its most general form, avoiding previously used assumptions about the equality of any of the Michaelis-Menten parameters for the two anomers (20, 40). In particular, we show that the simultaneous presence of α- and β-anomers of a sugar that are competing for transport by a carrier is fully accounted for by introducing factors and in the denominator of the corresponding classical Michaelis-Menten equation (Eqs. S108 and S109):

| (5) |

and

| (6) |

where [C] is the total molar concentration of the carrier. Vmax, Km, and kcat have the usual meanings, viz., the maximal velocity, Michaelis constant, and the turnover number, respectively. Superscripts α and β denote the individual values of Vmax, Km, and kcat that are specific for each anomer under equilibrium exchange conditions. υα and υβ are the equilibrium exchange rates of membrane transport.

It is more convenient to express Eqs. 5 and 6 in terms of normalized rates of transport, which could be readily calculated from kie values using Eq. 4:

| (7) |

and

| (8) |

As established earlier using 1D 19F NMR, at equilibrium, the ratio of the concentrations of the two anomers in each compartment is constant and can be defined by the parameter a:

| (9) |

Making the substitutions [α] = a[S] and [β] = (1 − a)[S] into Eqs. 7 and 8 gives (also see the equivalent Eqs. S111 and S112) the following:

| (10) |

and

| (11) |

In Eqs. 10 and 11, the following definitions are made to obtain the apparent Michaelis-Menten parameters:

| (12) |

| (13) |

and

| (14) |

The specificity constant kcat/Km is an important measure of the catalytic efficiency of an enzyme or carrier on a particular substrate (1). In the context of carrier-mediated facilitated diffusion, kcat/Km is equivalent to the rate constant of the transmembrane exchange when and can be interpreted as the overall membrane permeability of the substrate (41). Unlike the apparent rate constants and transport rates, the overall membrane permeability, defined as Vmax/Km (or normalized by the amount of enzyme or carrier in the medium and expressed as kcat/Km), does not depend on the substrate concentration. Additionally, the value of Vmax/Km is the same for the equilibrium exchange, zero-trans influx, and zero-trans efflux kinetics, which makes it an important characteristic of a carrier-mediated membrane transporter (41).

From Eqs. 12, 13, and 14, it follows that we can calculate the individual specificity constants as (see Eqs. S118 and S119 for derivation)

| (15) |

and

| (16) |

Thus, we proceeded to fit the model of Eqs. 10 and 11 to the obtained dependencies of kie (converted to the values of using Eq. 4) on the total substrate concentration [S] (Table 1). This procedure yielded values of , and (listed in Table 2), which provided estimates of the individual specificity constants of GLUT1 toward the two anomers ( and ) by using Eqs. 15 and 16. The determined kcat/Km values are listed in the last column of Table 2.

Discussion

Stability of RBCs in inosine medium

RBCs require a constant supply of energy in their suspension medium to maintain their shape and regulated oxygen affinity. The energy is largely dissipated in the regeneration of ATP, the cell’s “energy currency,” from inorganic phosphate and adenosine diphosphate. In vivo, the natural energy-supply substrate for human RBCs is Glc (in the blood plasma). As a consequence, during in vitro experiments on RBCs, it is usual to add glucose as a metabolic substrate for maintenance of physiological ATP levels. However, because Glc would inevitably interact with GLUT1 during the fluorosugar NMR experiments, it was important to remove all endogenous glucose in the RBC preparations. Under such conditions, only 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate remains as an energy source for the RBCs (originally at ∼5 mM), and this normally lasts for only 1–2 h at 37°C, at which point the cells begin to convert to echinocytes (42, 43). Hence, an alternative energy substrate was required for the prolonged EXSY experiments.

In a previous RBC study of FDG-3, Potts and Kuchel used 10 mM inosine in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) (20). This purine nucleoside is transported by a specific nucleoside transporter in RBCs (44). Inosine undergoes phosphorolysis via purine nucleoside phosphorylase (E.C. 2.4.2.1) to yield ribose 1-phosphate, obviating the requirement for ATP hydrolysis to phosphorylate the saccharide. Then, the constituent atoms enter glycolysis via the pentose phosphate pathway (45). The use of 5 mM ascorbic acid (vitamin C; ascorbate at physiological pH) in Tris-HEPES-buffered saline has also been used as a medium for fluorosugar NMR experiments (21, 28, 29). However, this is not optimal because ascorbate, if oxidized by dissolved O2, is converted to dehydroascorbate, which is known to be transported via GLUT1 (46, 47). Thus, it might potentially interfere with fluoroglucose transport. In fact, it was recently shown that the binding of Glc by GLUT3 is substantially reduced in the presence of dehydroascorbate (14).

Moreover, as is clear from the results in Fig. 3, ascorbic acid is not metabolized in human RBCs, so it does not act as a source of free energy. Nevertheless, it may play a role in the reduction of α-tocopherol in the cell membrane (48). We surmise that the primary role of ascorbate in the Glc-free media (21, 28, 29) is to spontaneously transfer electrons to oxidized glutathione and NAD. In turn, NADH transfers electrons to Fe(III) in methemoglobin, thus keeping most of the hemoglobin in the RBCs in a diamagnetic state; this is optimal for the signal/noise and resolution in NMR spectra. Glc acts as both a source of free energy for the regeneration of ATP and as a reducing agent via its contribution to the conversion of NAD to NADH and NADP to NADPH. Thus, ascorbate is not required in a medium that contains an energy source that feeds into glycolysis at the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase step.

Tris is known to react with aldehydes of low molecular weight in aqueous solution, so it interacts with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (49) and potentially with the open-chain form of glucose and its fluorinated analogs. With this in mind, we avoided the ascorbate/Tris-based medium and developed a different buffer for the 19F NMR EXSY experiments; this was done by combining the known metabolically beneficial properties of inosine, pyruvate, and KCl. The results of Figs. 3 and 4 proved the stability of the RBCs under the new conditions for a prolonged time (at least 3 h at 37°C).

Transmembrane exchange kinetics

Membrane transport of Glc in RBCs is sufficiently rapid for equilibrium across the compartments to be achieved within a few seconds, and yet the transmembrane exchange at equilibrium is slow on the NMR timescale. In 1D 19F NMR spectra of FDGs in RBC suspensions, this is highlighted by the well-resolved resonances from the spin populations inside and outside the cells (19, 21). This fortuitous property, referred to as a “split peak effect,” enables the use of magnetization-exchange spectroscopy for the quantification of the kinetics of the transmembrane exchange (20, 21, 22, 50). Furthermore, the α- and β-anomers of these sugars have different 19F NMR chemical shifts, thus allowing an examination of the differences in the transport rates of the two anomers (19, 20, 21).

In the past, transport of fluorinated sugars has been described by permeability coefficients P (cm s−1), or apparent exchange rate constants k (s−1), which can be measured for each anomer. However, these values are functions of the solute concentration because the kinetics of the transmembrane exchange of Glc and its analogs are well described by Michaelis-Menten enzyme kinetics, with a steady state of the concentration of the carrier-Glc complex (51). Thus, the transport kinetics of a given monosaccharide should ideally be described by estimating the individual Michaelis-Menten parameters (Km, Vmax, kcat) for each of the two anomers. Because both anomers of a monosaccharide simultaneously compete for binding in the carrier active site (52, 53), there are additional theoretical complications in the kinetic theory (see Supporting Materials and Methods). Explicit modifications of the rate equations are required, and a general form of these has been worked out (40, 51).

Previous anomer-specific studies of glucose analogs in RBCs have relied on assumptions such as equality of the Michaelis constants for binding to GLUT1 for the α- and β-anomers. This enabled the authors to simplify their rate equations and attribute any differences in the anomeric transport rates to differences in the apparent Vmax (or kcat) values (20). However, the assumption of equal affinity is not generally valid because the recent crystal structure data show that the anomeric −OH group can directly participate in hydrogen bonding inside the active site of the transporter (14). Moreover, a single change in the configuration of one of the carbon atoms might lead to a significant change in the affinity of GLUT1 for a monosaccharide. E.g., the Michaelis constant of galactose (C-4 epimer of glucose) with GLUT1 is ∼10 times greater than that of glucose (54, 55). This highlights the importance of anomer-specific kinetic studies and implies that Km and Vmax for monosaccharide transport, reported in the literature as a single or common value, might not reflect the true complexity of the transport kinetics of the GLUTs (56).

Previously reported anomer-specific data on the transport of glucose via GLUT1 were contradictory. An early study by Faust concluded that the β-anomer of Glc penetrates the RBC membrane ∼3 times faster than the α-anomer (57). Miwa et al. reported ∼1.5 times faster influx of the β-anomer into cells but the same rate for the efflux of the two anomers (58). This report was consistent with the view of Barnett et al. (59) that the C-1 hydroxyl group of Glc interacts with GLUT1 only on influx but not on efflux.

Carruthers and Melchior reported no difference in transport rates and affinity by the glucose transporter of the two anomers of Glc by using inhibition-uptake studies of radioactive Glc (52) in intact RBCs. This result was confirmed in a more recent study by the same group, and they concluded that GLUT1 does not prefer any specific anomer of Glc (40) in RBC ghosts. Other reports have indicated that the β-anomer is favored at higher temperatures whereas the α-anomer is preferred at lower temperatures (53) and that the α-anomer is 37% more efficient in promoting the GLUT1 conformational change than the β-anomer (60). Using a similar methodology to our study (equilibrium exchange magnetization-transfer experiments), Kuchel et al. measured the transport rates of Glc at 40°C and concluded that the transport of the α-anomer was ∼1.7 times faster than that of the β-anomer (61).

London and Gabel used analogs of glucose with fluorine substituted at position C-1 to halt the mutarotation between the two anomeric species (50). Thus, two 1-fluoro-1-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG-1) analogs of glucose were used in two separate experiments to probe their transport rates. The transport rate of FDG-1β at 37°C was significantly higher than that of FDG-1α (50). An earlier study of Barnett et al. reported that the entry of sorbose into RBCs was inhibited by both anomers of FDG-1, with inhibition constants of ∼15 mM (β) and ∼80 mM (α) (62), thus confirming weaker affinity of the α-form to GLUT1.

The transport mechanism of GLUT1 involves several conformational changes of the protein as reported in the recent structural studies (13, 14). Thus, the individual anomers might be acted upon at different rates at each of the given transport/binding steps, which complicates the comparison between the overall anomer-specific rates. Specifically, the overall transport rates would depend on the choice of the measurement assay conditions. Furthermore, the kinetic rate constants and the values of Vmax/kcat/Km would be different for equilibrium exchange, zero-trans, zero-cis, infinite-trans, and infinite-cis experiments (41, 51, 54). Additional complications arise from the fact that the previously reported experiments were different with respect to the measurement mode: some of them employed direct quantification of the transport rates of monosaccharides, whereas others used an inhibition type of experiments by measuring the influx/efflux of other competing metabolites. More importantly, however, the transport rates in their own right are not sufficient for the discrimination of the GLUT1 efficiency in transporting various Glc analogs and their anomers because, as discussed above, these values are dependent on the actual substrate concentration used in the experiment.

With this in view, we propose the use of the simple NMR-based assay, as described in this work, to discriminate the catalytic efficiency of GLUT1 for transport of various fluorine-labeled monosaccharides by measuring the kcat/Km values obtained in equilibrium exchange 19F NMR EXSY experiments. The advantage of the proposed approach is that these values can be obtained simultaneously for both anomers of a monosaccharide without requiring separation of the two anomeric species (which is not possible in aqueous media) or solution compartments. In addition, kcat/Km values are equal for the equilibrium exchange, zero-trans efflux, and zero-trans influx experiments, thus accounting for a range of conditions under which they could be measured and compared for different sugar anomers (41, 54). Thus, our approach allows more facile comparison of the GLUT1 catalytic efficiency on different substrates, including anomeric species of the same sugar.

Overall, the efflux rate constants obtained in our study (Table 1) agree well with previously reported values for the same or related sugars (20, 21). Our results given in Table 1 confirm that the apparent efflux rate constants decrease with increasing substrate concentration, that the α-anomer is transported faster than the β-anomer for these sugars, and that FDG-3 is transported faster than FDG-2, which in turn is transported faster than FDG-4 (21).

For FDG-3, we estimated slightly higher rate constants than reported by O’Connell et al. (21). We postulate that this was due to the presence of 5 mM ascorbate in the medium used previously by these researchers. Indeed, our rate constants for FDG-3 are more similar to those reported by Potts and Kuchel using experiments that were carried out in the presence of inosine (but no pyruvate) rather than ascorbate (20). Nevertheless, Dickinson et al. (22) reported even higher efflux rate constants for FDG-3; their values were in the range 2.12–2.40 s−1 (β) and 1.99–2.48 s−1 (α) (obtained at a substrate concentration of 10 mM). As the authors indicated, such high values could be due to the fact that all the blood donors were pregnant women and the RBCs might have been atypical.

It was also clear that the variations in transport rate with increasing sugar concentration were not equivalent for each sugar (e.g., FDG-4α was transported more slowly than FDG-2α at a concentration of 6.2 mM but at an equal rate at a concentration of 24.8 mM). This clearly complicates a structural interpretation of these data; however, an easier comparison between the permeability of various sugars/anomers is done via the estimated specificity constants.

From the data of Table 2, it was evident that variation in specificity constants (kcat/Km) of GLUT1 for the different fluorosugars for the most part followed the patterns in the concentration-dependence data in Table 1. Specifically, the specificity constant was substantially larger for FDG-3 than for FDG-2, which in turn was larger than for FDG-4 (t-test p < 0.01). Interestingly, although the kcat/Km value of the α-anomer of FDG-3 was twice that of FDG-2α and three times that of FDG-4α, the catalytic efficiency of GLUT1 for the β-anomer of FDG-3 was also twice that of FDG-2β but almost nine times that of FDG-4β. In addition, for each fluorosugar, GLUT1 had a higher specificity constant for the α-anomer than the β-anomer. As noted below, this is surmised to be a consequence of the anomeric preference of binding by GLUT1, which was previously interpreted in terms of a simple alternating conformation model (21, 50).

Interpretation of kinetic data in the context of GLUT1 structure

We can consider the specificity constant kcat/Km as an indicator of the catalytic efficiency of GLUT1 toward a particular anomeric species. As discussed by Percival and Withers, although Km values are not reliable indicators of ground-state affinity, the values of Vmax/Km (or, equivalently, kcat/Km) are more easily interpreted, as they reflect the activation energy barrier of the transition state, with changes indicating the variation in binding interactions between different substrates (63). In the context of membrane transport, the specificity constants are representative of binding at the rate-determining step in the overall transport mechanism (in terms of elementary steps, this incorporates the binding event, the transport event, and the release event, with the transport event consisting of multiple steps in GLUT1's conformational reorganization (14)).

The recent high-resolution crystal structure of GLUT3 protein with bound Glc (Protein Data Bank (PDB): 4ZW9 (14)) can be used to interpret the interatomic/chemical forces governing the binding of substrates to GLUT-like proteins. GLUT3 is the main transporter of Glc in neurons and shares 64.4% identity with GLUT1 (64). Because all the amino acid residues that are responsible for the binding of Glc are invariant between GLUT1 and GLUT3, we used the residue numbering of GLUT3 below to be consistent with the original study (14). In this analysis, GLUT3 was selected over GLUT1 because its structure is of higher resolution. Also, GLUT3 had pure Glc bound, whereas GLUT1 was bound with n-nonyl-β-D-glucopyranoside.

According to Deng et al., the hydrogen bonds formed in the binding of both glucose anomers involve the same residues, including those to the anomeric −OH group (14). The authors indicate that the α-anomer was more abundant (∼69%) in the crystallized protein than the β-anomer despite the fact that the α-form is the minor species of Glc in solution (∼36%). Although the corresponding anomeric ratio of binding of the fluorosugars to GLUT1 is not known, the larger kcat/Km values of the three FDG α-anomers obtained in this work also indicate their stronger stabilization of binding in the transport transition state compared to the respective β-anomers.

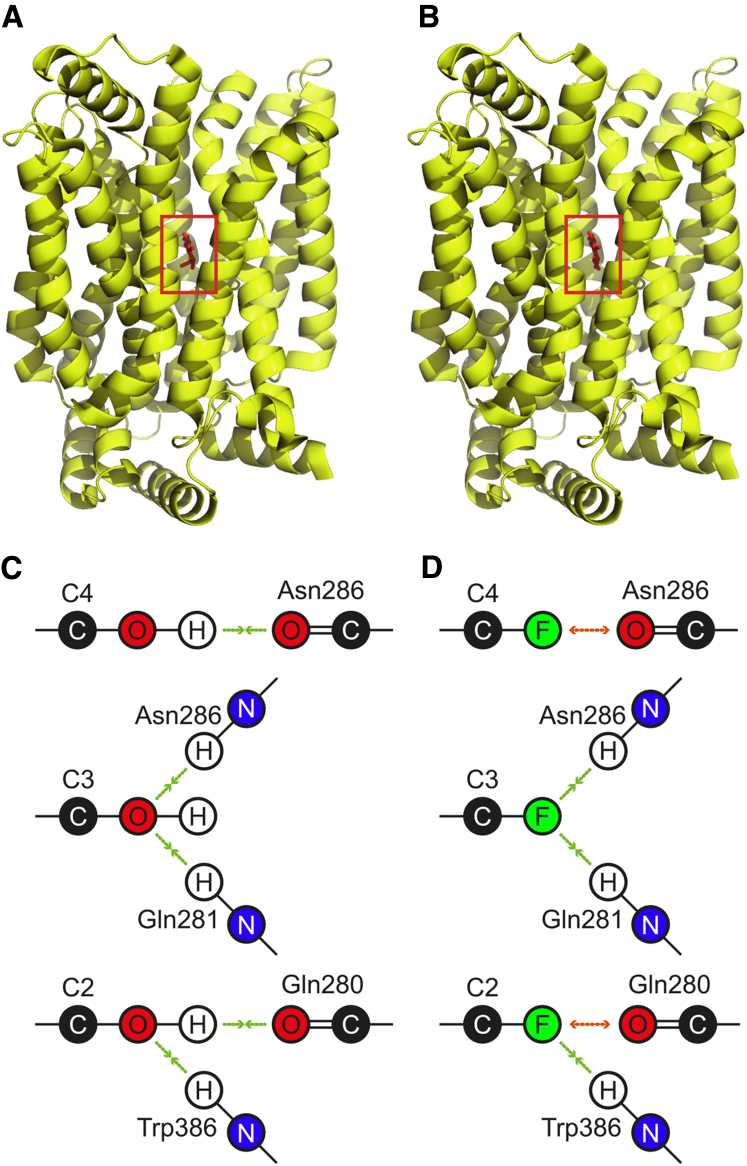

The structural data provided by Deng et al. allow deliberation on the impact of deoxyfluorination at the 2-, 3-, and 4-positions of the glucose scaffold. Both Glc anomers were shown to form hydrogen bonds between C2-OH, C3-OH, and C4-OH groups and the protein, involving the same amino acid residues in the protein’s active site for each anomer (14). Therefore, in the following, we consider the binding of the F-substituted moieties without considering the differences between the two anomers.

Specifically, as described by Deng et al., C4-OH serves as a hydrogen-bond donor with the carbonyl group of Asn286; C3-OH serves as a hydrogen-bond acceptor with the amide side chains of Asn286 and Gln281; and finally, C2-OH is both a hydrogen-bond donor with the carbonyl of Gln280 and a hydrogen-bond acceptor with the amine of Trp386. These interactions are shown schematically in Fig. 8.

Figure 8.

Binding of Glc by GLUTs according to the PDB: 4ZW9 structure (14). (A) The crystal structure of GLUT3 with bound α-Glc (highlighted by the red rectangle). (B) The crystal structure of GLUT3 with bound β-Glc. (C) The participation of −OH groups of Glc at positions C2, C3, and C4 in binding to GLUT3. (D) The putative effect of deoxyfluorination at positions C2, C3, and C4 on the interactions between Glc and GLUT3 (and, by analogy, GLUT1). To see this figure in color, go online.

If a fluorine atom is substituted for the −OH of the C4-OH moiety, an equivalent hydrogen bond cannot be formed, and electrostatic repulsion may exist between the oxygen atom of Asn286 and the F atom of FDG-4 (although the F atom in FDG-4 could also have an attractive interaction with the carbonyl dipole of Asn286 (65)). In contrast, when F substitutes for the −OH of C3-OH, it can still form two hydrogen bonds, potentially leading to a higher apparent binding affinity of FDG-3 in comparison with FDG-4. In the case of FDG-2, there is an intermediate situation upon substitution of −F for −OH because the C2-OH serves as both a hydrogen-bond donor and acceptor. Therefore, the binding affinity of FDG-2 will be lower than FDG-3 but higher than FDG-4. Although these considerations entail ground-state binding, the obtained kcat/Km values of the three monodeoxyfluorinated glucoses (Tables 1 and 2) are nevertheless consistent with this picture.

Conclusions

We extended the steady-state Michaelis-Menten theory to be applicable to the case in which two competing molecular species bind to and cross the cell membrane via the same carrier protein. This new theory was used to determine the values of the kinetic parameters for three different monofluorinated glucoses (FDG-2, FDG-3, and FDG-4; Fig. 1) as substrates of GLUT1.

To our knowledge, we have shown for the first time that the individual specificity constants of a transporter protein for two anomeric species can be determined from equilibrium exchange experiments without physical separation of the anomers. The experimental approach entails measuring the apparent efflux rate constants of the monosaccharide substrates at several different concentrations. The theoretical development involved extension of the Michaelis-Menten equation to encompass description of the membrane transport kinetics when two anomeric species of the same compound are in direct competition for interaction with the carrier.

The developed method was used to quantify RBC membrane transport of the anomers of three monofluorinated analogs of glucose in a modified medium designed to provide stable metabolic properties of the cells over the lifetime of the experiment. This allowed us to evaluate the specific interaction (specificity constants) of the carrier individually for both anomers of each of the studied fluorosugars. The estimated specificity constants showed faster transport of the α-anomer versus the β-anomer for all investigated substrates, with FDG-4 featuring the largest anomeric preference. A qualitative interpretation of the differences in the transmembrane exchange rates of FDG-2, FDG-3, and FDG-4 in terms of the perturbation of binding of these monosaccharides to GLUT1, caused by specific F/OH substitutions, has been provided.

Our developed approach and mathematical analysis could become important for a variety of applications such as drug development and systems biology. In turn, such studies can be used to probe responses of membrane proteins in their native environment, e.g., in testing whether disease conditions lead to altered permeability of particular carbohydrates or to changes in cell-membrane integrity (22). Fluorosugars are also of great interest as imaging agents. Radiolabeled FDG-2 is currently the most used PET (positron emission tomography)-imaging substrate for cancer diagnosis (66), whereas fluorinated fructose analogs have recently been shown to hold promise as imaging agents for GLUT5 expression in breast cancer tissue (67).

Author Contributions

D.S., B.L., and P.W.K. designed the study. D.S., C.Q.F., and P.W.K. performed the experiments. D.S., I.K., and P.W.K. analyzed the data. D.S. and P.W.K. developed the theory. D.S., B.L., and P.W.K. prepared the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ann Kwan for the maintenance of the NMR spectrometer and valuable discussions on setting it up for our experiments.

The work was supported by the grant RPG-2015-211 to B.L. and P.W.K. from the Leverhulme Trust and the Australian Research Council (ARC) grant DP140102596 to P.W.K.

Editor: Ian Forster.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods and 13 figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(18)31112-3.

Contributor Information

Dmitry Shishmarev, Email: dmitry.shishmarev@anu.edu.au.

Philip W. Kuchel, Email: philip.kuchel@sydney.edu.au.

Supporting Citations

References (68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77) appear in the Supporting Material.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Nelson D.L., Cox M.M. W.H. Freeman and Company; New York: 2008. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carruthers A. Facilitated diffusion of glucose. Physiol. Rev. 1990;70:1135–1176. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thorens B., Mueckler M. Glucose transporters in the 21st century. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;298:E141–E145. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00712.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueckler M., Thorens B. The SLC2 (GLUT) family of membrane transporters. Mol. Aspects Med. 2013;34:121–138. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorga F.R., Lienhard G.E. Changes in the intrinsic fluorescence of the human erythrocyte monosaccharide transporter upon ligand binding. Biochemistry. 1982;21:1905–1908. doi: 10.1021/bi00537a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macheda M.L., Rogers S., Best J.D. Molecular and cellular regulation of glucose transporter (GLUT) proteins in cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 2005;202:654–662. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganapathy V., Thangaraju M., Prasad P.D. Nutrient transporters in cancer: relevance to Warburg hypothesis and beyond. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;121:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amann T., Hellerbrand C. GLUT1 as a therapeutic target in hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2009;13:1411–1427. doi: 10.1517/14728220903307509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adekola K., Rosen S.T., Shanmugam M. Glucose transporters in cancer metabolism. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2012;24:650–654. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328356da72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ung P.M., Song W., Schlessinger A. Inhibitor discovery for the human GLUT1 from homology modeling and virtual screening. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016;11:1908–1916. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Granchi C., Fortunato S., Minutolo F. Anticancer agents interacting with membrane glucose transporters. Medchemcomm. 2016;7:1716–1729. doi: 10.1039/C6MD00287K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calvaresi E.C., Hergenrother P.J. Glucose conjugation for the specific targeting and treatment of cancer. Chem. Sci. (Camb.) 2013;4:2319–2333. doi: 10.1039/C3SC22205E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng D., Xu C., Yan N. Crystal structure of the human glucose transporter GLUT1. Nature. 2014;510:121–125. doi: 10.1038/nature13306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng D., Sun P., Yan N. Molecular basis of ligand recognition and transport by glucose transporters. Nature. 2015;526:391–396. doi: 10.1038/nature14655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Champagne P.A., Desroches J., Paquin J.F. Organic fluorine as a hydrogen-bond acceptor: recent examples and applications. Synthesis. 2015;47:306–322. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Street I.P., Armstrong C.R., Withers S.G. Hydrogen bonding and specificity. Fluorodeoxy sugars as probes of hydrogen bonding in the glycogen phosphorylase-glucose complex. Biochemistry. 1986;25:6021–6027. doi: 10.1021/bi00368a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Withers S.G., Street I.P., Percival M.D. Fluorinated carbohydrates as probes of enzyme specificity and mechanism. In: Taylor N.F., editor. Fluorinated Carbohydrates. American Chemical Society; 1988. pp. 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glaudemans C.P. Mapping of subsites of monoclonal, anti-carbohydrate antibodies using deoxy and deoxyfluoro sugars. Chem. Rev. 1991;91:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potts J.R., Hounslow A.M., Kuchel P.W. Exchange of fluorinated glucose across the red-cell membrane measured by 19F-n.m.r. magnetization transfer. Biochem. J. 1990;266:925–928. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Potts J.R., Kuchel P.W. Anomeric preference of fluoroglucose exchange across human red-cell membranes. 19F-n.m.r. studies. Biochem. J. 1992;281:753–759. doi: 10.1042/bj2810753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Connell T.M., Gabel S.A., London R.E. Anomeric dependence of fluorodeoxyglucose transport in human erythrocytes. Biochemistry. 1994;33:10985–10992. doi: 10.1021/bi00202a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickinson E., Arnold J.R., Fisher J. Determination of glucose exchange rates and permeability of erythrocyte membrane in preeclampsia and subsequent oxidative stress-related protein damage using dynamic-19F-NMR. J. Biomol. NMR. 2017;67:145–156. doi: 10.1007/s10858-017-0092-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dacie J.V., Lewis S.M. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh, Scotland: 1975. Practical Haematology. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaka A., Keeler J., Freeman R. An improved sequence for broadband decoupling: WALTZ-16. J. Magn. Reson. 1983;52:335–338. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Claridge T.D. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2009. High-resolution NMR Techniques in Organic Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown F.F., Campbell I.D., Rabenstein D.C. Human erythrocyte metabolism studies by 1H spin echo NMR. FEBS Lett. 1977;82:12–16. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(77)80875-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolfram S. Wolfram Media; Champaign, IL: 2003. The Mathematica Book. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim H.W., Rossi P., DiMagno S.G. Structure and transport properties of a novel, heavily fluorinated carbohydrate analogue. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:9082–9083. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bresciani S., Lebl T., O’Hagan D. Fluorosugars: synthesis of the 2,3,4-trideoxy-2,3,4-trifluoro hexose analogues of D-glucose and D-altrose and assessment of their erythrocyte transmembrane transport. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2010;46:5434–5436. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01128b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bloch R. Inhibition of glucose transport in the human erythrocyte by cytochalasin B. Biochemistry. 1973;12:4799–4801. doi: 10.1021/bi00747a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson G., Kuchel P.W., Irving M.G. A simple procedure for selective inversion of NMR resonances for spin transfer enzyme kinetic measurements. J. Magn. Reson. 1985;63:314–319. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McConnell H.M. Reaction rates by nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Chem. Phys. 1958;28:430–431. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shishmarev D., Kuchel P.W. NMR magnetization-transfer analysis of rapid membrane transport in human erythrocytes. Biophys. Rev. 2016;8:369–384. doi: 10.1007/s12551-016-0221-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montel-Hagen A., Sitbon M., Taylor N. Erythroid glucose transporters. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2009;16:165–172. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328329905c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raftos J.E., Bulliman B.T., Kuchel P.W. Evaluation of an electrochemical model of erythrocyte pH buffering using 31P nuclear magnetic resonance data. J. Gen. Physiol. 1990;95:1183–1204. doi: 10.1085/jgp.95.6.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cloherty E.K., Heard K.S., Carruthers A. Human erythrocyte sugar transport is incompatible with available carrier models. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10411–10421. doi: 10.1021/bi953077m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller D.M. The kinetics of selective biological transport. III. Erythrocyte-monosaccharide transport data. Biophys. J. 1968;8:1329–1338. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(68)86559-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller D.M. The kinetics of selective biological transport. IV. Assessment of three carrier systems using the erythrocyte-monosaccharide transport data. Biophys. J. 1968;8:1339–1352. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(68)86560-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naftalin R.J., Rist R.J. Re-examination of hexose exchanges using rat erythrocytes: evidence inconsistent with a one-site sequential exchange model, but consistent with a two-site simultaneous exchange model. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1191:65–78. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leitch J.M., Carruthers A. α- and β-monosaccharide transport in human erythrocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2009;296:C151–C161. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00359.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stein W.D., Litman T. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2015. Channels, Carriers, and Pumps: An Introduction to Membrane Transport. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pagès G., Szekely D., Kuchel P.W. Erythrocyte-shape evolution recorded with fast-measurement NMR diffusion-diffraction. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2008;28:1409–1416. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong P. The basis of echinocytosis of the erythrocyte by glucose depletion. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2011;29:708–711. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Young J.D., Yao S.Y., Baldwin S.A. Equilibrative nucleoside transport proteins. In: Bernhardt I., Ellory J.C., editors. Red Cell Membrane Transport in Health and Disease. Springer-Verlag; 2003. pp. 321–337. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grimes A. Blackwell Scientific Publications; Oxford, UK: 1980. Human Red Cell Metabolism. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Himmelreich U., Drew K.N., Kuchel P.W. 13C NMR studies of vitamin C transport and its redox cycling in human erythrocytes. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7578–7588. doi: 10.1021/bi970765s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sage J.M., Carruthers A. Human erythrocytes transport dehydroascorbic acid and sugars using the same transporter complex. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2014;306:C910–C917. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00044.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.May J.M. Ascorbate function and metabolism in the human erythrocyte. Front. Biosci. 1998;3:d1–d10. doi: 10.2741/a262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bubb W.A., Berthon H.A., Kuchel P.W. Tris buffer reactivity with low-molecular-weight aldehydes: NMR characterization of the reactions of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate. Bioorg. Chem. 1995;23:119–130. [Google Scholar]

- 50.London R.E., Gabel S.A. Fluorine-19 NMR studies of glucosyl fluoride transport in human erythrocytes. Biophys. J. 1995;69:1814–1818. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80051-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stein W.D., Lieb W.R. Academic Press; Orlando: 1986. Transport and Diffusion Across Cell Membranes. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carruthers A., Melchior D.L. Transport of α- and β-D-glucose by the intact human red cell. Biochemistry. 1985;24:4244–4250. doi: 10.1021/bi00336a065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Janoshazi A., Solomon A.K. Initial steps of α- and β-D-glucose binding to intact red cell membrane. J. Membr. Biol. 1993;132:167–178. doi: 10.1007/BF00239006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ginsburg H. Galactose transport in human erythrocytes. The transport mechanism is resolved into two simple asymmetric antiparallel carriers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1978;506:119–135. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(78)90439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ginsburg H., Yeroushalmy S. Effects of temperature on the transport of galactose in human erythrocytes. J. Physiol. 1978;282:399–417. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leitch J.M., Carruthers A. ATP-dependent sugar transport complexity in human erythrocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C974–C986. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00335.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Faust R.G. Monosaccharide penetration into human red blood cells by an altered diffusion mechanism. J. Cell. Comp. Physiol. 1960;56:103–121. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030560205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miwa I., Fujii H., Okuda J. Asymmetric transport of D-glucose anomers across the human erythrocyte membrane. Biochem. Int. 1988;16:111–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barnett J.E., Holman G.D., Munday K.A. Evidence for two asymmetric conformational states in the human erythrocyte sugar-transport system. Biochem. J. 1975;145:417–429. doi: 10.1042/bj1450417a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Appleman J.R., Lienhard G.E. Kinetics of the purified glucose transporter. Direct measurement of the rates of interconversion of transporter conformers. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8221–8227. doi: 10.1021/bi00446a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuchel P.W., Chapman B.E., Potts J.R. Glucose transport in human erythrocytes measured using 13C NMR spin transfer. FEBS Lett. 1987;219:5–10. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barnett J.E., Holman G.D., Munday K.A. Structural requirements for binding to the sugar-transport system of the human erythrocyte. Biochem. J. 1973;131:211–221. doi: 10.1042/bj1310211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Percival M.D., Withers S.G. Binding energy and catalysis: deoxyfluoro sugars as probes of hydrogen bonding in phosphoglucomutase. Biochemistry. 1992;31:498–505. doi: 10.1021/bi00117a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kayano T., Fukumoto H., Bell G.I. Evidence for a family of human glucose transporter-like proteins. Sequence and gene localization of a protein expressed in fetal skeletal muscle and other tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:15245–15248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Müller K., Faeh C., Diederich F. Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: looking beyond intuition. Science. 2007;317:1881–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1131943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ametamey S.M., Honer M., Schubiger P.A. Molecular imaging with PET. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:1501–1516. doi: 10.1021/cr0782426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Soueidan O.M., Trayner B.J., Cheeseman C.I. New fluorinated fructose analogs as selective probes of the hexose transporter protein GLUT5. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015;13:6511–6521. doi: 10.1039/c5ob00314h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ellory J.C., Young J.D. Academic Press; London: 1982. Red Cell Membranes: a Methodological Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moore W.J. Longman; Harlow, Essex, UK: 1972. Physical Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 70.King E.L., Altman C. A schematic method of deriving the rate laws for enzyme-catalyzed reactions. J. Phys. Chem. 1956;60:1375–1378. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Orsi B.A. A simple method for the derivation of the steady-state rate equation for an enzyme mechanism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1972;258:4–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(72)90961-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Indge K.J., Childs R.E. A new method for deriving steady-state rate equations suitable for manual or computer use. Biochem. J. 1976;155:567–570. doi: 10.1042/bj1550567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kuchel P.W., Ralston G.B. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1988. Schaum’s Outline of Theory and Problems of Biochemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cornish-Bowden A. An automatic method for deriving steady-state rate equations. Biochem. J. 1977;165:55–59. doi: 10.1042/bj1650055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mulquiney P.J., Kuchel P.W. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2003. Modelling Metabolism with Mathematica. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Britton H.G. Permeability of the human red cell to labelled glucose. J. Physiol. 1964;170:1–20. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pagès G., Puckeridge M., Kuchel P.W. Transmembrane exchange of hyperpolarized 13C-urea in human erythrocytes: subminute timescale kinetic analysis. Biophys. J. 2013;105:1956–1966. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kuchel P.W. Nuclear magnetic resonance of biological samples. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 1981;12:155–231. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.