ABSTRACT

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeds are a common presentation to emergency departments in the UK. The Glasgow Blatchford score (GBS) predicts the outcome of patients at presentation. Current UK and European guidelines recommend outpatient management for a GBS of 0. In the current study, our aim was to assess whether extending the GBS allows for early discharge while maintaining patient safety. We also analysed whether pathologies could be missed by discharging patients too early. Data were retrospectively collected on patients admitted with symptoms of an upper GI bleed between 1 October 2013 and 10 June 2016. The GBS was calculated and gastroscopy reports were obtained for each patient. In total, 399 patients were identified, 63 of whom required therapy. The negative predictive value (NPV) for excluding the need for endoscopic intervention with a GBS score up to 1 was 100%. Extending the score to 2 and 3 reduced the NPV to 98.53% and 98.77%, respectively. The NPV of GBS in excluding any diagnosis at 0 was 43.55%. Two patients died as a result of GI bleeding, with a GBS score of 3. Therefore, we can conclude that, for non-variceal bleeds, the GBS can be extended to 2 for safe outpatient management, thereby reducing the number of bed days and pressure for urgent endoscopies.

KEYWORDS: Upper gastrointestinal bleeding, Glasgow Blatchford score

Background

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) haemorrhage is a common presentation to emergency departments with an incidence of 84–170/100,000 adults/year in the UK.1–3 It results in approximately 50,000–70,000 hospital admissions per year.2 The estimated cost of this to the NHS is approximately £155.5 million, of which approximately 60% (£93 million) results from the inpatient length of stay.4 Mortality rates from GI bleeding are between 7% and 14%, with even higher rates for inpatients who have a GI bleed.2–5

Several scoring systems have been designed to assist with the risk stratification of upper GI haemorrhages. These include the Glasgow Blatchford Score (GBS) and the Rockall Score (RS). The GBS is a formal risk assessment tool for upper GI haemorrhages and uses the patient's blood results, blood pressure, known history and presentation findings to identify how urgently patients require endoscopic therapy.6 The RS was designed to predict the risk of death based on pre- and post-endoscopic findings.7

Comparison studies showed that the GBS is as effective as, if not superior to, the RS at predicting mortality from GI bleeding.8–11 The GBS has also been found to be better at predicting the need for transfusion as well as for endoscopic or surgical intervention.5

Current recommendations from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK2 and the European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE)12 are that patients scoring 0 on the GBS can be safely discharged with an urgent outpatient endoscopy; this recommendation has been validated by several studies.11,13,14

More recent evidence suggests that a GBS >0 is also associated with low-risk GI bleeds; however, the exact threshold that will facilitate safe patient discharge remains a contentious issue, with scores ranging from 1 to 3.5,15–17

In the current study, we assessed whether the GBS threshold for discharge can be extended, as postulated by other studies, and identified the GBS score that accurately predicts low-risk outcomes. We also analysed whether pathologies can be missed by discharging patients without endoscopic assessment.

Methods

Data were collected retrospectively on patients over the age of 16 who attended the Emergency Department or were inpatients at Salford Royal Hospital, UK with symptoms of an upper GI bleed (haematemesis or melaena) between 1 October 2013 and 10 June 2016. Patients who did not have an endoscopy were excluded. Using the electronic patient records (EPR), the clinical history, vital signs, laboratory and endoscopic results, and information on patient outcomes were recorded. The GBS was calculated and the composite endpoints of 30-day mortality, rebleeding or the necessity for endoscopic or other therapies (surgical or radiological) to treat bleeding were used.

Furthermore, the results of the endoscopy were reviewed as to whether pathology was identified as the cause of GI bleeding. The GBS was correlated with the need for intervention and the pathology identified.

The data were analysed using MedCalc statistical software and negative predictive values were calculated.

This is a service improvement-based project using retrospectively collected data via directorate audit, entailing no impact on patient care. Ethical approval was therefore not required and there were no conflicts of interests.

Results

In total, 399 patients were identified, 220 (55.1%) of whom were male and 179 (44.9%) female. Patients were aged from 16 to 97 years, with a mean age of 59.9 years and median of 64 years.

The presenting complaints (from admission clerking or endoscopy request) of these patients were recorded as: haematemesis (170; 42.6%), coffee ground vomiting (81; 20.3%), melaena (140; 35.1%), haematemesis and melaena (5; 1.2%), anaemia (2; 0.5%) and collapse (1; 0.2%).

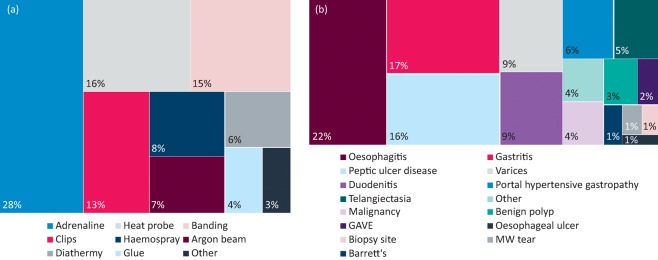

The median GBS was 5 and the median time to endoscopy was 24–48 h. Of the 399 patients, 63 (15.8%) received a therapy (60 underwent endoscopy, two received a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, and one was referred for surgery) (Table 1). A range of endoscopic interventions were used (Fig 1). As expected, a higher GBS was associated with the need for therapy (Table 1). In accordance with current guidelines, no patients with a score of 0 required therapy and, as the score extended to 1, this remained the same, giving a negative predictive value (NPV) for a GBS less than or equal to 1 of 100%. Two patients with a GBS of 2 required therapy. Both patients underwent variceal banding; however, there were no stigmata of bleeding on endoscopy and the score of 2 was solely for known liver disease. No patients with a score of 3 required therapy. By extending the score to less than or equal to 2, the NPV fell from 100% to 98.53% (94.45–99.62%) then increased when the score was extended to 3 to 98.77% (95.35–99.69%) (Table 3). With a score of 4 or more, an increasing proportion of patients received therapy, resulting in a decreasing NPV for every point the GBS increased by (Table 2).

Table 1.

Number of patients with an endoscopic diagnosis or requiring therapy by GBS

| GBS | Total | Diagnosis | Therapy required | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | ||

| 0 | 62 | 35 (56%) | 27 (44%) | 0 (0%) | 62 (100%) |

| 1 | 41 | 22 (54%) | 19 (46%) | 0 (0%) | 41 (100%) |

| 2 | 33 | 21 (64%) | 12(36%) | 2 (6%) | 31 (94%) |

| 3 | 27 | 17 (63%) | 10 (37%) | 0 (0%) | 27 (100%) |

| 4 | 26 | 20 (77%) | 6 (23%) | 4 (15%) | 22 (85%) |

| 5 | 21 | 19 (90%) | 2 (10%) | 6 (29%) | 15 (71%) |

| 6 | 13 | 12 (92%) | 1 (8%) | 1 (8%) | 12 (92%) |

| 7 | 37 | 26 (70%) | 11 (30%) | 7 (19%) | 30 (81%) |

| 8 | 22 | 19 (86%) | 3 (14%) | 2 (9%) | 20 (91%) |

| >8 | 117 | 113 (97%) | 4 (3%) | 41 (35%) | 76 (65%) |

| Total | 399 | 304 (76%) | 95 (24%) | 63 (16%) | 336 (84%) |

GBS = Glasgow Blatchford score

Fig 1.

Block diagram showing frequency of different therapies used to treat gastrointestinal bleeding (a) and block diagram showing frequency of diagnoses at endoscopy (b) for all patients. GAVE = gastral antral vascular ectasia; MW tear = Mallory Weiss tear

Table 2.

Number of patients requiring therapy; sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV with increasing GBS

| GBS | Therapeutic intervention (n = 63) | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 100% (94.31–100) | 18.45% (14.45–23.02) | 18.69% (17.93–19.48) | 100% |

| ≤1 | 0 | 100% (94.31–100) | 30.65% (25.77–35.89) | 21.28% (20.12–22.50) | 100% |

| ≤2 | 2 (1.49%) | 96.83% (89.00–99.61) | 39.88% (34.61–45.34) | 23.19% (21.50–24.98) | 98.53% (94.45–99.62) |

| ≤3 | 2 (1.24%) | 96.83% (89.00–99.61) | 47.92% (42.47–53.41) | 25.85% (23.76–28.05) | 98.77% (95.35–99.69) |

| ≤4 | 6 (3.17%) | 90.48% (80.41–96.42) | 54.56% (48.97–59.88) | 27.14% (24.43–30.03) | 96.83% (93.40–98.50) |

| ≤5 | 12 5.71%) | 80.95% (69.09–89.75) | 58.93% (53.46–64.24) | 26.98% (23.67–30.57) | 94.29% (90.78–96.51) |

| ≤6 | 13 (5.83%) | 79.37% (67.30–88.53) | 62.5% (57.08–67.69) | 28.41% (24.77–32.36) | 94.17% (90.81–96.35) |

| ≤7 | 19 (7.31%) | 68.25% (55.31–79.42) | 71.43% (66.27–76.20) | 30.94% (26.08–36.25) | 92.31% (89.25–94.55) |

| ≤8 | 21 (7.45%) | 65.08% (52.03–76.66) | 77.38% (72.53–81.74) | 35.04% (29.21–41.36) | 92.2% (89.36–94.33) |

GBS = Glasgow Blatchford score; NPV = negative predictive value; PPV = positive predictive value

Overall, 19 (4.76%) patients rebled. The diagnoses associated with this were peptic ulcers (n=6), malignancy (n=3), varices (n=5), gastritis (n=3), portal hypertensive gastropathy (n=1) and one unknown (investigated for a lower GI source). In total, 26 (6.52%) patients died within 30 days of presentation. Of these, six were as a direct result of upper GI bleeding, 17 from other diagnoses, and, for three patients, no cause of death was recorded on the EPR. No patients with a score less than or equal to 2 had died or rebled at 30 days after admission. By contrast, for a GBS of 3, there were two patient mortalities (one secondary to metastatic oesophageal cancer and the other because of an aorto-oesophageal fistula). Both these patients had been deemed unsuitable for further therapy because of the extent of their malignancy and comorbidities.

Of the 399 patients, 304 (76.2%) had a diagnosis documented on endoscopy and 95 (23.8%) had a normal oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD). A range of pathologies were identified (Fig 1). Again, as the GBS increased, there was an greater likelihood of pathology (Table 3). Positive predictive values (PPVs) for pathology on endoscopy for GBS less than or equal to 8 reached 96.58%. Even at low GBS scores, pathologies were found. The NPV for diagnosis at a GBS score of 0 was 43.55% (33.04–54.67%). Although many of the pathology findings were gastritis and/or oesophagitis, there were pathologies present that required ongoing follow-up, such as Barrett's oesophagus. This indicates that a low GBS does not exclude the need for a diagnostic OGD.

Table 3.

Number of patients with endoscopic diagnosis; sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV as GBS increases

| GBS | Pathology (n=304) | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 35 (56.45%) | 88.90% (84.35–91.85) | 27.85% (19.21–37.85) | 79.35% (77.14–81.40) | 43.55% (33.04–54.67) |

| ≤1 | 57 (55.34%) | 81.25% (76.40–85.48) | 48.42% (38.04–58.90) | 83.45% (80.46–86.05) | 44.66% (37.12–52.46) |

| ≤2 | 78 (58.78%) | 74.34% (69.05–79.16) | 61.05% (50.50–70.89) | 85.93% (82.48–88.79) | 42.65% (36.68–48.84) |

| ≤3 | 95 (58.78%) | 68.75% (63.21–73.92) | 71.58%(61.40–80.36) | 88.56% (84.79–91.49) | 41.72% (36.73–46.88) |

| ≤4 | 115 (60.85%) | 62.17% (56.46–67.64) | 77.89 % (68.22–85.77) | 90.00% (85.93–92.99) | 39.15% (34.97–43.50) |

| ≤5 | 134 (53.81%) | 55.92% (50.14–61.58) | 80.00% (70.54–87.51) | 89.95% (85.53–93.12) | 36.19% (32.55–40.00) |

| ≤6 | 146 (65.47%) | 51.97%(46.20–57.71) | 81.05% (71.72–88.37) | 89.77% (85.10–93.10) | 34.53% (31.18–38.04) |

| ≤7 | 172 (66.15%) | 43.42% (37.77–49.20) | 92.63% (85.41–96.99) | 94.96% (90.14–97.49) | 33.85% (31.35–36.44) |

| ≤8 | 191 (67.77%) | 37.17%(31.72–42.87) | 95.79% (89.57–98.84) | 96.58% (91.46–96.68) | 32.27% (30.20–34.41) |

GBS = Glasgow Blatchford score; NPV = negative predictive value; PPV = positive predictive value

Discussion

Upper GI bleeding is a common reason for admission to hospital and, although it can lead to mortality, there is a range of causalities and a spectrum of severity on presentation. The GBS is a reliable and easy tool that can be used rapidly and by all clinicians to ascertain the urgency of investigation. With the ever-increasing demand on hospital and endoscopy services, the ability to differentiate between low risk (no therapeutic intervention or transfusion needed) and high risk (likelihood of transfusion, therapeutic intervention, rebleeding or mortality) provides a key opportunity for clinical prioritisation of both endoscopic interventions and hospital bed days.

Our data suggest that, for non-variceal bleeds, patients with a GBS of 2 or less can be safely discharged with early outpatient investigation. Stanley et al carried out a multinational study and concluded that the best threshold for outpatient management was a GBS of 1, which carried a mortality rate of 0.4%.5 This was also shown by Laursen et al in a large multinational study of 2,305 patients, which suggested that a GBS ≤1 would result in safe outpatient management and reduce hospital admissions by 15–20%.17

Furthermore, some studies have recommended increasing the threshold further. Stevens et al found that a GBS ≤2 and patient age under 70 years old could be used to define low-risk patients who could be managed as outpatients.15 Masoaka et al and Srivajaskanthan et al looked at 93 and 174 patients, respectively, attending emergency departments with GI bleeding and stratified them as low or high risk retrospectively. Both groups found that patients could be deemed low risk and suitable for early discharge using a GBS cut-off of ≤2.18,19

Similarly, Aquarius et al found that patients attending three hospitals in The Netherlands were low risk when scoring 2 or less on the GBS. At this threshold, the sensitivity of whether treatment was required was 99.4%. The authors concluded this low-risk subgroup were eligible for outpatient management, which might reduce hospital admissions and healthcare costs.20 Further to this, one study indicated that patients with a GBS of 2 or less could be suitable for outpatient management doubling the number of eligible patients for early discharge.16

From our results, two patients with a GBS of 3 died within 30 days of presentation. The causes of death were metastatic oesophageal cancer and an oesophagealaortic fistula. Although neither case was suitable for endoscopic or other therapy because of comorbidities and extensive malignant disease, the mortality rate is of considerable concern and precludes safe outpatient management.

Two patients with a GBS of 2 received endoscopic therapy; both required variceal banding and scored 2 because of a history of liver disease. Both patients presented with coffee ground vomiting and their histories were not typical of a variceal bleed. Neither had a fall in haemoglobin or any adverse features (low blood pressure or tachycardia) throughout their admission. However, given that both patients required therapy, we recommend that patients with a history of liver disease and, hence, with possible varices, are managed more cautiously and are not suitable for discharge and early outpatient management.

In extending the GBS to 2 or less, there could be significant benefits to hospitals with minimal extra expense or effort required from the clinician. The score encompasses aspects of the history, blood results and observations that are taken as routine on a patient's presentation to hospital. Specialist knowledge is not required to calculate or interpret the resulting score, which is simply a number ranging from 0 to 23. Therefore, it can be applied in emergency departments and acute medical units to facilitate early discharge and prevent patients spending hours nil by mouth waiting for an endoscopy slot. In our study, 62 patients (15.5%) had a GBS of 0, making them eligible for discharge. Extending the score to 2 (excluding two patients with liver disease) increased the number of potential discharges by 72 patients, which is a further 18.0%. The ability to discharge 33.5% of upper GI bleeds could feasibly reduce pressure on endoscopy departments, where trying to accommodate inpatients necessitates altering lists with little notice and time liaising with wards and porters to transfer patients to the unit. It could also reduce the burden on inpatient beds, which are currently at a premium, and deliver a cost saving to hospitals. A study from 2015 aimed to collect data on costs associated with acute upper GI bleeding in the UK from six university hospitals. The authors estimated mean in-hospital costs to be £2,458 per patient, with 60% of this cost attributed to inpatient bed days, 26% to diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopies and 8% to blood transfusions. Combining these data with UK population figures, the authors estimated the total annual cost of initial hospital treatment in the UK to be £155.5 million, with £93 million (60%) attributable to inpatient stays.21

Although endoscopic treatment was not required with a GBS of 0–1, having a low score does not exclude a pathology that necessitates follow-up (eg Barrett's oesophagus). Therefore, it is essential that these patients still undergo investigation to avoid missing findings that could jeopardise patient safety.

A limitation of our study was that the need for blood transfusion was not assessed. Although the necessity for this is prognosticated by the GBS, it was not taken into consideration as to whether this would affect the patient's need for an acute admission. Neither did we take into account other factors affecting a patient's presentation, eg social issues, and we included current inpatients in our data. Therefore, it is difficult to comment on how many more patients could have been discharged in real numbers. Nevertheless, we used broad inclusion criteria (any GI bleed symptom) and did not exclude patients for comorbidity or age, which reflects the population attending an emergency department.

Further prospective studies would be advisable to corroborate results, and we would recommend selecting patients presenting with GI bleeds to the emergency department.

Conclusion

Patients presenting with a non-variceal upper GI bleed with a GBS of 2 or less could be considered suitable for discharge with outpatient investigations planned, thereby reducing the number of bed days and pressure on endoscopy services.

References

- 1.Rockall TA. Logan RF. Devlin HB. Northfield TC. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom. Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. BMJ. 1995;311:222–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in over 16s – management. Clinical Guideline CG141. London:: NICE; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network Management of acute upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. SIGN Clinical Guideline 105. Edinburgh:: SIGN; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell HE. Stokes EA. Bargo D, et al. Costs and quality of life associated with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: cohort analysis of patients in a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007230. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanley AJ. Laine L. Dalton HR, et al. Comparison of risk scoring systems for patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: international multicentre prospective study. BMJ. 2017;356:i6432. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blatchford O. Murray W. Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet. 2000;356:1318–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rockall TA. Logan RF. Devlin HB. Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38:316–21. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.3.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevenson J. Bowling K. Littlewood J. Stewart D. Validating the Glasgow Blatchford Upper GI bleeding scoring system. Gut. 2013;62:A21–2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanley AJ. Dalton HR. Blatchford O, et al. Multicentre comparison of the Glasgow Blatchford and Rockall scores in the prediction of clinical end-points after upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:470–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laursen SB. Hansen JM. Schaffalitzky de Muckadell O. The Glasgow Blatchford score is the most accurate assessment of patients with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1130–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanley AJ. Ashley D. Dalton HR, et al. Outpatient management of patients with low-risk upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage: multicentre validation and prospective evaluation. Lancet. 2009;373:42–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gralnek IM. Dumonceau JM. Kuipers EJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:a1–46. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1393172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Girardin M. Bertolini D. Ditisheim S, et al. Use of Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score reduces hospital stay duration and costs for patients with low-risk upper GI bleeding. Endoscopy Int Open. 2014;2:E74–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pang SH. Ching JY. Lau JY, et al. Comparing the Blatchford and pre-endoscopic Rockall score in predicting the need for endoscopic therapy in patients with upper GI hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1134–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephens JR. Hare NC. Warshow U, et al. Management of minor upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the community using the Glasgow Blatchford Score. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1340–6. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32831bc3ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Jeune IR. Gordon AL. Farrugia D, et al. Safe discharge of patients with low-risk upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Can use of Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score be extended? Acute Med. 2011;10:176–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laursen SB. Dalton HR. Murray IA, et al. Performance of the new thresholds of Glasgow Blatchford score in managing patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masaoka T. Suzuki H. Hori S. Aikawa N. Hibi T. Blatchford scoring system is a useful scoring system for detecting patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding who do not need endoscopic intervention. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1404–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Srirajaskanthan R. Conn R. Bulwer C. Irving P. The Glasgow Blatchford scoring system enables accurate risk stratification of patients with upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:868–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aquarius M. Smeets FG. Konijn HW, et al. Prospective multicenter validation of the Glasgow Blatchford bleeding score in the management of patients with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage presenting at an emergency department. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27:1011–6. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell HE. Stokes EA. Bargo D, et al. Costs and quality of life associated with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: cohort analysis of patients in a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007230. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]