Abstract

The term Idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia (IIH) was first introduced almost 70 years ago when symptomatic hypercalcemia developed in children after receiving high doses of vitamin D for the prevention of rickets. The underlying pathophysiology remained unknown until recessive mutations in CYP24A1 encoding Vitamin D3-24-hydroxylase were discovered. The defect in vitamin D degradation leads to an accumulation of active 1,25(OH)2D3 with subsequent hypercalcemia. Enhanced renal calcium excretions lead to hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis. Meanwhile, the phenotypic spectrum associated with CYP24A1 mutations has significantly broadened. Patients may present at all age groups with symptoms originating from increased serum calcium levels as well as from increased urinary calcium excretions, i.e. kidney stones. Possible long term sequelae comprise chronic renal failure as well as cardiovascular disease. Here, we present a family with two affected siblings with differing clinical presentation as an example for the phenotypic variability of CYP24A1 defects.

Keywords: Idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia, Nephrocalcinosis, Nephrolithiasis, CYP24A1, Vitamin D

Highlights

-

•

CYP24A1 mutations result in increased vitamin D sensitivity.

-

•

Associated phenotypes range from infantile hypercalcemia to kidney stone disease.

-

•

Potential long-term sequelae include chronic renal failure.

-

•

Future research needs to focus on potential treatments to limit vitamin D activation.

1. Introduction

Idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia (IIH) was first described as a novel clinical entity when symptomatic hypercalcemia developed in infants after receiving high doses of vitamin D (approximately 4000 IE/day) for the prevention of rickets in Great Britain in the 1950s (Lightwood and Stapleton, 1953; Fanconi, 1951). Affected children present with failure-to-thrive, weight loss, dehydration, polyuria, muscular hypotonia, and lethargy, typical symptoms of severe hypercalcemia. Concomitant hypercalciuria typically leads to the development of early nephrocalcinosis. Infants who receive daily oral vitamin D for the prevention of rickets usually present in the first year of life. Metabolic studies indicated that the hypercalcemia was due to an increased intestinal calcium uptake and associated with an increased renal calcium excretion (Morgan et al., 1956). A potential connection to vitamin D supplementation was early recognized and IIH was suspected to represent a state of vitamin D hypersensitivity in children being especially susceptible to vitamin D (Morgan et al., 1956). Despite these early advancements, the exact link between vitamin D supplementation and the development of hypercalcemia in affected infants remained obscure. Especially, contradictory data regarding serum levels of active 1,25(OH)2D3 were reported: while some authors observed elevated levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 (McTaggart et al., 1999), other affected children were found to have levels within the normal range (Nguyen et al., 2010). Though it remained unknown if IIH at all represented a hereditary disease, single familial cases pointed to a genetic background, pedigree analyses indicated an autosomal-recessive inheritance (McTaggart et al., 1999).

Finally, in 2011, recessive mutations in CYP24A1 were discovered as the first underlying genetic defect in IIH (Schlingmann et al., 2011). The CYP24A1 gene codes for the cytochrome P450 enzyme 24-hydroxylase, a multi-catalytic enzyme responsible for a 5-step, vitamin D-inducible, C-24-oxidation pathway that converts 1,25(OH)2D3 into water soluble calcitroic acid thereby inactivating it (Makin et al., 1989). The initial patient cohort consisted of six infants who received daily vitamin D supplementation in the range of 500 IU, and four children who, in the 1980s in the German Democratic Republic, had been given single doses of 600,000 IU vitamin D2. Whereas the first cohort developed symptoms after several months indicating a critical role of a certain cumulative dose of exogenous vitamin D, bolus doses in the second cohort resulted in the development of symptoms resembling acute vitamin D toxicity within days to weeks after administration. After acute treatment, serum calcium levels largely normalized, but tended to be continuously at the upper normal limit during follow-up. Levels of iPTH remained suppressed in the majority of patients and levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 mostly persisted within the upper normal range, reflecting a continuous activation of vitamin D metabolism (Schlingmann et al., 2011). Later, mutations in SLC34A1 encoding renal proximal-tubular sodium-phosphate co-transporter NaPi-IIa were discovered as a second genetic defect underlying IIH (Schlingmann et al., 2016). Patients with NaPi-IIa defects share critical phenotypic and biochemical features of patients with CYP24A1 defects but in addition exhibit phosphate depletion due to primary renal phosphate wasting.

We here present a family with two affected siblings displaying different phenotypic presentations of CYP24A1 associated disease in infancy and adolescence, respectively.

2. Case report

The female index patient (F1.1) was born at term. The neonatal period was uneventful. The infant was breastfed and received regular vitamin D prophylaxis for the prevention of rickets with a dose of 400 IU per day. She presented at the age of 10 months with failure to thrive. The laboratory work-up revealed borderline hypercalcemia and a suppressed iPTH level (see Table 1). Renal function tests and blood gases were normal. Urine analysis revealed hypercalciuria (12 mg/kg/day) and renal ultrasound demonstrated severe nephrocalcinosis. Genetic analyses excluded Williams syndrome (chr7q11.23 deletion (Perez Jurado et al., 1996)). Under the suspected diagnosis of IIH, a low-calcium diet was initiated and vitamin D prophylaxis was stopped. Therapeutic regimens led to a normalization of serum calcium levels while iPTH levels remained suppressed. While urine analyses demonstrated a normalization of calcium excretions, follow-up ultrasound examinations showed persistent nephrocalcinosis. At the age of three years, the low-calcium diet was stopped which led to a re-occurrence of hypercalciuria and suspected aggravation of nephrocalcinosis. The patient was subsequently treated with citrate as well as hydrochlorothiazide until the age of nine years. Thereafter, serum calcium levels and calcium excretions have remained in the upper normal range, nephrocalcinosis has persisted without further aggravation, and renal function is normal.

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory data of patients F2.1 and F2.2.

| Variable | Patient F2.1 | Patient F2.2 |

|---|---|---|

| Age at presentation | 10 months | 13 years |

| Vitamin D prophylaxis | 400 IU/day | 400 IU/day |

| Clinical symptoms | Failure to thrive | Nephrolithiasis |

| Laboratory findings | ||

| At initial presentation | ||

| S-Ca (mmol/L)(2.1–2.6) | 2.7 | 3.0 |

| iPTH (pg/mL)(14–72) | 2.8 | 9.7 |

| 25-OH-vit D3 (ng/mL)(20–65) | 42 | 73 |

| 1,25-(OH)2-vit D3 (pg/mL)(17–74) | nd | 109 |

| Ca/creatinine ratio (mg/mg) | 0.68 (<0.60)a | 0.32 (<0.22)a |

| At last follow-up | ||

| S-Ca (mmol/L)(2.1–2.6) | 2.28 | 2.8 |

| iPTH (pg/mL) (14–72) | 14.4 | 11.9 |

| 25-OH-vit D3 (ng/mL) (20–65) | 43 | 82 |

| 1,25-(OH)2-vit D3 (pg/mL) (17–74) | 69 | 81 |

| Ca/creatinine ratio (mg/mg)(<0.22)a | 0.32 | 0.30 |

Reference values for Ca/creatinine ratios according to Sargent et al. J Pediatr 1993.

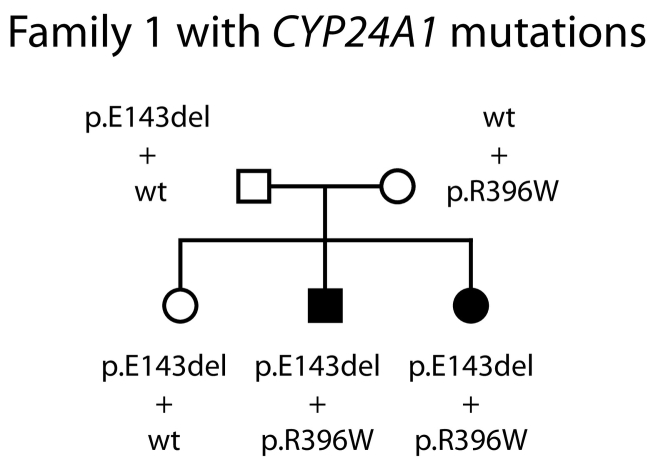

The past medical history of the patient's older brother was unremarkable with an uneventful neonatal period and infancy. He had also received regular vitamin D prophylaxis (400 IU/(day)). At the age of 13 years, he presented with abdominal pain and suspected appendicitis. Abdominal ultrasound revealed a 10 mm concrement in the right renal pelvis as well as a smaller concrement of 6 mm in the left kidney while there was no medullary nephrocalcinosis. Laboratory evaluations demonstrated hypercalcemia of 3 mmol/L, a suppressed iPTH of 9.7 pg/mL, and a level of active 1,25(OH)2D3 of 109 pg/mL (Table 1). The calcium excretion in a spot urine sample was elevated (0.32 g/g, reference range <0.25). Both kidney stones were removed by ureterorenoscopy. A reduction of oral calcium resulted in a normalization of serum calcium levels as well as urinary calcium excretions. The laboratory testing during follow-up revealed serum calcium levels at the upper limit of the reference range and a persisting suppression of iPTH (Table 1). During a follow-up of three years, there is no reoccurrence of nephrolithiasis. The older sister as well as both parents are clinically unaffected. Unfortunately, there is no laboratory data on calcium and vitamin D metabolism available. Genetic testing for IIH was initiated that revealed compound-heterozygous mutations p.E143del and p.R396W in the CYP24A1 gene in both affected siblings while the parents as well as the unaffected sister were found to be heterozygous mutation carriers (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pedigree of family 1 with mutated CYP24A1 alleles indicated. The two affected children are compound-heterozygous for CYP24A1 mutations p.E143del and p.R396W, whereas both parents and the asymptomatic sister carry one mutated allele each. The two identified mutations represent the two most common mutated CYP24A1 alleles in the European population, both mutations have been described before, and lead to a complete loss of enzyme function in vitro.

3. Discussion

After the initial description of mutations in CYP24A1, the initial findings were substantiated by numerous follow-up-studies. These case series also significantly extended the clinical spectrum caused by CYP24A1 deficiency demonstrating a wide range of phenotypic presentations that will be summarized and discussed in the following.

CYP24A1 mutations identified in the initial report were functionally analyzed in an in vitro system demonstrating a complete loss-of-function of the CYP24A1 enzyme with lack of 24-hydroxylated vitamin D metabolites (Schlingmann et al., 2011). Moreover, an in vivo test method for the determination of 24-hydroxylated vitamin D metabolites in patients` serum was developed (Kaufmann et al., 2014). Calculation of the 25-OH-D3 to 24,25-(OH)2D3 enables the sensitive detection of patients with bi-allelic CYP24A1 mutations and lack of 24-hydroxylase enzyme activity irrespective of an individual's vitamin D status (Kaufmann et al., 2014; Kaufmann et al., 2017). Interestingly, a small set of mutations in the CYP24A1 gene comprising p.E143del, p.R396W, and p.L409S is detected in high frequency in the majority of patients of Caucasian descent irrespective of the severity of biochemical abnormalities, age at manifestation and clinical phenotype. All three variants were already identified in the initial report and shown to lead to a complete loss of enzyme function. They are listed in public exome and genome databases (ExAC, gnomAD) and represent variants that have a significant frequency in the general population (Table 2). Therefore, from the genetic point of view, patients with CYP24A1 defects display an exceptionally homogenous cohort. This also concerns the number of affected alleles as the vast majority of studies describes patients with bi-allelic CYP24A1 mutations.

Table 2.

Most frequent CYP24A1 loss-of-function mutations.

| Gene | Genomic coordinates | Variant (nt) | Variant (aa) | SNP number | ExAC frequencya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP24A1 | 20-52789466-CCTT-C | c.427_429delGAA | p.E143del | – | 0.000930 |

| CYP24A1 | 20-52774675-G-A | c.1186C > T | p.R396W | rs114368325 | 0.001106 |

| CYP24A1 | 20-52774635-A-G | c.1226T > C | p.L409S | rs6068812 | 0.001158 |

Several studies have described single patients or small case series of typical IIH patients who carried bi-allelic CYP24A1 mutations and clinically presented with symptomatic hypercalcemia in infancy (Dauber et al., 2012; Fencl et al., 2013; Skalova et al., 2013; Castanet et al., 2013; Dinour et al., 2015). These studies mainly confirmed phenotypic and laboratory characteristics that had been reported in IIH patients since the 1950s and were also reported for the initial cohort of patients with CYP24A1 mutations. Uniformly describing patients with bi-allelic CYP24A1 mutations, these publications also supported the initial assumption of a primarily recessive trait of “classic” IIH. Furthermore, the initial report as well as one additional study described families in which, after typical manifestation of IIH in a first infant, vitamin D prophylaxis was omitted in a younger sibling who subsequently remained asymptomatic despite sharing the identical bi-allelic CYP24A1 mutations (Schlingmann et al., 2011; Castanet et al., 2013). On one hand, these findings argue for a certain cumulative dose of exogenous vitamin D needed for the development of symptomatic hypercalcemia, on the other hand, suggest an incomplete penetrance of inherited CYP24A1 defects. The significant increase in the incidence of IIH that was observed in the 1950s in the UK as well as later in Poland during phases of high vitamin D supplementation (i.e. 4000 IU/day) also suggest a close relationship between dosage of exogenous vitamin D and disease penetrance (Pronicka et al., 2017). The index patient presented here received a currently recommended dose of 400 IU per day vitamin D3 and manifested in infancy with failure to thrive. Renal ultrasound demonstrated a significant nephrocalcinosis. However biochemical parameters were rather mild contrasting the severe symptomatic hypercalcemia observed in “typical” IIH cases and the diagnosis could have easily been missed. These findings might reflect an early diagnosis in the presence of slowly evolving clinical symptoms patient but could also suggest a generally mild disease phenotype in the index patient.

In addition to cases of “typical” IIH, numerous publications have reported adolescent and adult patients with identical bi-allelic mutations in CYP24A1 who mainly presented with recurrent kidney stone disease, typically during childhood or young adult age (Nesterova et al., 2013; Dinour et al., 2013; Meusburger et al., 2013; Colussi et al., 2014; Wolf et al., 2014; Jobst-Schwan et al., 2015). Laboratory examinations mostly demonstrated a milder degree of hypercalcemia, but similarly suppressed iPTH levels compared to infants with “classic” IIH.

Some of these patients were followed for decades and without knowledge of the underlying etiology received diverse medical interventions including parathyroidectomy to treat hypercalcemia and suspected hyperparathyroidism before reliable measurements of iPTH became available (Jacobs et al., 2014). Summarizing published cases with genetically proven CYP24A1 deficiency, a recent study concluded that more than a third of reported patients with bi-allelic CYP24A1 mutations presented beyond infancy (Cools et al., 2015). These long-term data obtained in adult patients are crucial for our understanding of possible complications of a sustained activation of vitamin D metabolism caused by CYP24A1 defects. Particularly, a deterioration of renal function has been reported in a number of cases (Dinour et al., 2013; Colussi et al., 2014; Wolf et al., 2014). However, it remains to be investigated in future studies whether this reported decline in glomerular filtration rate is the consequence of repeated episodes of kidney stone disease, acute kidney injury, and urologic interventions or whether it represents a primary complication of the disease itself.

Moreover, extensive vascular calcifications have been observed in single adult patients suggesting that an augmented 1,25(OH)2D3 activity with subsequent changes in calcium metabolism might also represent a risk factor for coronary artery disease and arterial occlusive disease (Colussi et al., 2014).

Another clinical presentation that deserves special attention is a primary manifestation of CYP24A1 mediated disease in women during pregnancy or shortly after labour (Dinour et al., 2015; Shah et al., 2015; Woods et al., 2016; Kwong and Fehmi, 2016). Of note, all reported women carried bi-allelic CYP24A1 mutations. These cases demonstrate that women with CYP24A1 defects are at risk to develop severe clinical symptoms during pregnancy which represents a state of increased 1,25(OH)2D3 production despite being able to limit vitamin D activation under normal circumstances. Interestingly, two of these women had presented with kidney stones prior to their pregnancies (Dinour et al., 2015; Shah et al., 2015). Clinical disturbances of hypercalcemia in pregnancy include nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and polyuria, but more importantly mother and child are put at risk for severe complications such as arterial hypertension, nephrolithiasis, pancreatitis, life threatening hypercalcemic crises, and fetal demise (Woods et al., 2016; Norman et al., 2009). Moreover, neonatal morbidity and mortality are increased due to intrauterine growth restriction, low birth weight, and preterm delivery (Rey et al., 2016).

The clinical findings as well as biochemical changes observed in the affected brother presented here are characteristic for a “late” manifestation of IIH. He had remained clinically asymptomatic before, showed lack of overt hypercalcemia, and renal ultrasound revealed no nephrocalcinosis that represents an almost uniform finding in young patients. Clinical presentation with nephrolithiasis as well as age at initial manifestation can definitely be considered typical for “late” IIH. One could speculate if a determination of iPTH levels at an earlier age would have yielded suppressed values as this parameter is considered a sensitive diagnostic tool also for asymptomatic and normocalcemic patients (Molin et al., 2015; Sayer, 2015).

So far, only a limited number of studies provide clinical and laboratory data for individuals with heterozygous CYP24A1 mutations mostly examining family members of index patients with bi-allelic CYP24A1 mutations (Colussi et al., 2014; Cools et al., 2015; Molin et al., 2015). These demonstrate similar, albeit milder biochemical abnormalities comprising increased levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 and low levels of iPTH, and, at the same time, show an increased frequency of kidney stones. The finding of a single heterozygous CYP24A1 mutation observed in a patient who developed symptomatic hypercalcemia after vitamin D bolus prophylaxis (600.000 IU p.o.) as well as the detection of a mild degree of hypercalcemia in a cohort of clinically asymptomatic neonates carrying a single heterozygous CYP24A1 mutation also support the assumption of a milder, but detectable phenotype caused by CYP24A1 haploinsufficiency (Schlingmann et al., 2011; Molin et al., 2015). Heterozygous mutation carriers may be prone to develop clinically evident disease only under circumstances promoting increased vitamin D activation, i.e. prematurity/early infancy, high doses of exogenous vitamin D, or during pregnancy (see above). Especially in account of the observed frequency of heterozygous CYP24A1 variants in the general population, these findings demand larger studies exploring the spectrum of biochemical changes and clinical phenotypes in carriers of a single heterozygous CYP24A1 mutation.

In contrast to a spectrum of well-defined therapeutic measures for acute symptomatic hypercalcemia (Rodd and Goodyer, 1999; Davies and Shaw, 2012), specific therapeutic strategies for patients with CYP24A1 defects who display a mild degree of hypercalcemia but present with recurrent renal symptoms are only insufficiently examined to date. Usually, regular vitamin D supplementation is stopped in affected infants and older patients and their parents are advised to avoid vitamin D supplements during later life. In this context, the identification of patients with CYP24A1 defects, i.e. by genetic testing or analysis of 24-hydroxylated metabolites, could enable the selective omission of vitamin D supplementation in individuals at risk before development of clinical symptoms as shown for two younger siblings of hypercalcemic patients with CYP24A1 defects (Schlingmann et al., 2011; Castanet et al., 2013). As a tendency to higher serum calcium levels and higher urinary calcium excretions has been observed during summer months, it might be recommended to avoid excessive sunlight exposure and prevent seasonal peaks of cutaneous vitamin D synthesis (Figueres et al., 2015). The authors conclude that although IIH typically manifests after vitamin D supplementation, sunlight exposure and thus cutaneous vitamin D synthesis may critically influence the clinical course during follow-up. On the other hand, little is known about the risk of vitamin D deficiency with low levels of 25(OH)D3 in patients with CYP24A1 defects. While these might prevent excessive vitamin D activation via renal 1α-hydroxylase, very low 25(OH)D3 levels might be insufficient for extrarenal 1,25(OH)2D3 synthesis.

Specifically, a low-calcium diet as implemented in the presented cases is not recommended on a routine basis and requires close monitoring due to its potential to induce calcium deficiency and iatrogenic rickets as well as an increase in nutritional oxalate absorption that may aggravate the risk for developing renal calcifications and oxalate kidney stones. A similar caution should be applied to the use of sodium cellulose phosphate (SCP), a non-absorbable cation exchange resin used for the removal of excess calcium from the body though SCP has been successfully used in patients with infantile hypercalcemia over a period of several years without relevant side effects (Huang et al., 2006; Mizusawa and Burke, 1996).

Often, corticosteroids are used for the treatment of symptomatic hypercalcemia as they are known to inhibit enteral calcium absorption. Next to this intestinal effect, corticosteroids have been shown to induce CYP24A1 expression (Jones et al., 2012). However, the therapeutic efficacy of corticosteroids in patients with CYP24A1 defects was studied in detail by Colussi and colleagues who report a failure of corticosteroids to lower serum calcium levels, decrease urinary calcium excretions, and normalize iPTH levels (Colussi et al., 2014). These findings might indicate that the therapeutic effect in other disorders such as granulomatous disease mainly involves the induction of CYP24A1 rather than the intestinal effect.

Several studies have evaluated the use of ketoconazole in CYP24A1-mediated hypercalcemia at least for periods of several months (Nguyen et al., 2010; Nesterova et al., 2013; Tebben et al., 2012). Next to an inhibition of fungal cytochrome P450 enzymes azole derivates such as ketoconazole and fluconazole also suppress mammalian cytochrome P450 enzymes including 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) (Nguyen et al., 2010; Sayers et al., 2015). As the use of ketoconazole is limited by its side-effects and toxicity, fluconazole was introduced as a therapeutic alternative (Sayers et al., 2015). The authors demonstrated that even low doses produce a significant decline of 1,25(OH)2D3 levels in patients with bi-allelic CYP24A1 defects and a stabilization of serum calcium levels (Sayers et al., 2015). Very recently, a gain-of-function mutation has been identified in CYP3A4 leading to vitamin D-dependent rickets type 3 (Roizen et al., 2018). The affected patients exhibited low 25-OH-D3 as well as low 1,25(OH)2D3 levels. In vitro studies demonstrated a 10-fold higher CYP3A4 activity in inactivating 1,25(OH)2D3 compared to wildtype CYP3A4 and even a 2-fold higher activity compared to CYP24A1. These new findings further support earlier observations of the same group that a targeted induction of CYP3A4 by rifampin might be used to normalize elevated vitamin D metabolites in patients with CYP24A1 defects (Hawkes et al., 2017).

In summary, following the identification of CYP24A1 mutations as the underlying genetic defect in IIH, numerous studies have identified a large number of patients with identical CYP24A1 defects who clinically present at all ages with diverse clinical symptoms ranging from early severe symptomatic hypercalcemia to kidney stone disease in normocalcemic adults. An example for the phenotypic variability in siblings with an identical genetic defect was presented here. In the light of these findings, every single part of the original term Idiopathic Infantile Hypercalcemia (IIH) appears superseded and insufficient to describe our current knowledge of the spectrum of disease caused by CYP24A1 deficiency. Many question concerning the long-term outcome and potential treatments to prevent disease complications remain to be answered. This is especially true considering the frequency of proven loss-of-function mutations in CYP24A1 in the general population as well as the genetic heterogeneity demonstrated by identification of mutations in renal phosphate co-transporters NaPi-IIa and NaPi-IIc producing similar clinical and biochemical phenotypes including an imminent deterioration of renal function (Schlingmann et al., 2016; Dasgupta et al., 2014; Dinour et al., 2016).

References

- Castanet M., Mallet E., Kottler M.L. Lightwood syndrome revisited with a novel mutation in CYP24 and vitamin D supplement recommendations. J. Pediatr. 2013;163(4):1208–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colussi G., Ganon L., Penco S., De Ferrari M.E., Ravera F., Querques M., Primignani P., Holtzman E.J., Dinour D. Chronic hypercalcaemia from inactivating mutations of vitamin D 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1): implications for mineral metabolism changes in chronic renal failure. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2014;29(3):636–643. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools M., Goemaere S., Baetens D., Raes A., Desloovere A., Kaufman J.M., De Schepper J., Jans I., Vanderschueren D., Billen J., De Baere E., Fiers T., Bouillon R. Calcium and bone homeostasis in heterozygous carriers of CYP24A1 mutations: a cross-sectional study. Bone. 2015;81:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta D., Wee M.J., Reyes M., Li Y., Simm P.J., Sharma A., Schlingmann K.P., Janner M., Biggin A., Lazier J., Gessner M., Chrysis D., Tuchman S., Baluarte H.J., Levine M.A., Tiosano D., Insogna K., Hanley D.A., Carpenter T.O., Ichikawa S., Hoppe B., Konrad M., Savendahl L., Munns C.F., Lee H., Juppner H., Bergwitz C. Mutations in SLC34A3/NPT2c are associated with kidney stones and nephrocalcinosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014;25(10):2366–2375. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013101085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauber A., Nguyen T.T., Sochett E., Cole D.E., Horst R., Abrams S.A., Carpenter T.O., Hirschhorn J.N. Genetic defect in CYP24A1, the vitamin D 24-hydroxylase gene, in a patient with severe infantile hypercalcemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;97(2):E268–E274. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J.H., Shaw N.J. Investigation and management of hypercalcaemia in children. Arch. Dis. Child. 2012;97(6):533–538. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinour D., Beckerman P., Ganon L., Tordjman K., Eisenstein Z., Holtzman E.J. Loss-of-function mutations of CYP24A1, the vitamin D 24-hydroxylase gene, cause long-standing hypercalciuric nephrolithiasis and nephrocalcinosis. J. Urol. 2013;190(2):552–557. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinour D., Davidovits M., Aviner S., Ganon L., Michael L., Modan-Moses D., Vered I., Bibi H., Frishberg Y., Holtzman E.J. Maternal and infantile hypercalcemia caused by vitamin-D-hydroxylase mutations and vitamin D intake. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2015;30(1):145–152. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-2889-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinour D., Davidovits M., Ganon L., Ruminska J., Forster I.C., Hernando N., Eyal E., Holtzman E.J., Wagner C.A. Loss of function of NaPiIIa causes nephrocalcinosis and possibly kidney insufficiency. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2016;31(12):2289–2297. doi: 10.1007/s00467-016-3443-0. (Dec) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanconi G. Chronic disorders of calcium and phosphate metabolism in children. Schweiz. Med. Wochenschr. 1951;81(38):908–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fencl F., Blahova K., Schlingmann K.P., Konrad M., Seeman T. Severe hypercalcemic crisis in an infant with idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia caused by mutation in CYP24A1 gene. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2013;172(1):45–49. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1818-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueres M.L., Linglart A., Bienaime F., Allain-Launay E., Roussey-Kessler G., Ryckewaert A., Kottler M.L., Hourmant M. Kidney function and influence of sunlight exposure in patients with impaired 24-hydroxylation of vitamin D due to CYP24A1 mutations. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2015;65(1):122–126. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes C.P., Li D., Hakonarson H., Meyers K.E., Thummel K.E., Levine M.A. CYP3A4 induction by rifampin: an alternative pathway for vitamin D inactivation in patients with CYP24A1 mutations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017;102(5):1440–1446. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Coman D., McTaggart S.J., Burke J.R. Long-term follow-up of patients with idiopathic infantile hypercalcaemia. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2006;21(11):1676–1680. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0217-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs T.P., Kaufman M., Jones G., Kumar R., Schlingmann K.P., Shapses S., Bilezikian J.P. A lifetime of hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria, finally explained. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;99(3):708–712. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobst-Schwan T., Pannes A., Schlingmann K.P., Eckardt K.U., Beck B.B., Wiesener M.S. Discordant clinical course of vitamin-D-hydroxylase (CYP24A1) associated hypercalcemia in two adult brothers with nephrocalcinosis. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2015;40(5):443–451. doi: 10.1159/000368520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G., Prosser D.E., Kaufmann M. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D-24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1): its important role in the degradation of vitamin D. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012;523(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann M., Gallagher J.C., Peacock M., Schlingmann K.P., Konrad M., DeLuca H.F., Sigueiro R., Lopez B., Mourino A., Maestro M., St-Arnaud R., Finkelstein J.S., Cooper D.P., Jones G. Clinical utility of simultaneous quantitation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D by LC-MS/MS involving derivatization with DMEQ-TAD. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;99(7):2567–2574. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-4388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann M., Morse N., Molloy B.J., Cooper D.P., Schlingmann K.P., Molin A., Kottler M.L., Gallagher J.C., Armas L., Jones G. Improved screening test for idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia confirms residual levels of serum 24,25-(OH)2 D3 in affected patients. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017;32(7):1589–1596. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong W.T., Fehmi S.M. Hypercalcemic pancreatitis triggered by pregnancy with a CYP24A1 mutation. Pancreas. 2016;45(6):e31–e32. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightwood R., Stapleton T. Idiopathic hypercalcaemia in infants. Lancet. 1953;265(6779):255–256. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(53)90187-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makin G., Lohnes D., Byford V., Ray R., Jones G. Target cell metabolism of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 to calcitroic acid. Evidence for a pathway in kidney and bone involving 24-oxidation. Biochem. J. 1989;262(1):173–180. doi: 10.1042/bj2620173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTaggart S.J., Craig J., MacMillan J., Burke J.R. Familial occurrence of idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia. Pediatr. Nephrol. 1999;13(8):668–671. doi: 10.1007/s004670050678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meusburger E., Mundlein A., Zitt E., Obermayer-Pietsch B., Kotzot D., Lhotta K. Medullary nephrocalcinosis in an adult patient with idiopathic infantile hypercalcaemia and a novel CYP24A1 mutation. Clin. Kidney J. 2013;6(2):211–215. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sft008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizusawa Y., Burke J.R. Prednisolone and cellulose phosphate treatment in idiopathic infantile hypercalcaemia with nephrocalcinosis. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 1996;32(4):350–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1996.tb02569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molin A., Baudoin R., Kaufmann M., Souberbielle J.C., Ryckewaert A., Vantyghem M.C., Eckart P., Bacchetta J., Deschenes G., Kesler-Roussey G., Coudray N., Richard N., Wraich M., Bonafiglia Q., Tiulpakov A., Jones G., Kottler M.L. CYP24A1 mutations in a cohort of hypercalcemic patients: evidence for a recessive trait. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;100(10):E1343–E1352. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-4387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan H.G., Mitchell R.G., Stowers J.M., Thomson J. Metabolic studies on two infants with idiopathic hypercalcaemia. Lancet. 1956;270(6929):925–931. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(56)91518-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesterova G., Malicdan M.C., Yasuda K., Sakaki T., Vilboux T., Ciccone C., Horst R., Huang Y., Golas G., Introne W., Huizing M., Adams D., Boerkoel C.F., Collins M.T., Gahl W.A. 1,25-(OH)2D-24 hydroxylase (CYP24A1) deficiency as a cause of nephrolithiasis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013;8(4):649–657. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05360512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen M., Boutignon H., Mallet E., Linglart A., Guillozo H., Jehan F., Garabedian M. Infantile hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria: new insights into a vitamin D-dependent mechanism and response to ketoconazole treatment. J. Pediatr. 2010;157(2):296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman J., Politz D., Politz L. Hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy and the effect of rising calcium on pregnancy loss: a call for earlier intervention. Clin. Endocrinol. 2009;71(1):104–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez Jurado L.A., Peoples R., Kaplan P., Hamel B.C., Francke U. Molecular definition of the chromosome 7 deletion in Williams syndrome and parent-of-origin effects on growth. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1996;59(4):781–792. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronicka E., Ciara E., Halat P., Janiec A., Wojcik M., Rowinska E., Rokicki D., Pludowski P., Wojciechowska E., Wierzbicka A., Ksiazyk J.B., Jacoszek A., Konrad M., Schlingmann K.P., Litwin M. Biallelic mutations in CYP24A1 or SLC34A1 as a cause of infantile idiopathic hypercalcemia (IIH) with vitamin D hypersensitivity: molecular study of 11 historical IIH cases. J. Appl. Genet. 2017;58(3):349–353. doi: 10.1007/s13353-017-0397-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey E., Jacob C.E., Koolian M., Morin F. Hypercalcemia in pregnancy - a multifaceted challenge: case reports and literature review. Clin. Case Rep. 2016;4(10):1001–1008. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd C., Goodyer P. Hypercalcemia of the newborn: etiology, evaluation, and management. Pediatr. Nephrol. 1999;13(6):542–547. doi: 10.1007/s004670050654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roizen J.D., Li D., O'Lear L., Javaid M.K., Shaw N.J., Ebeling P.R., Nguyen H.H., Rodda C.P., Thummel K.E., Thacher T.D., Hakonarson H., Levine M.A. CYP3A4 mutation causes vitamin D-dependent rickets type 3. J. Clin. Invest. 2018;128(5):1913–1918. doi: 10.1172/JCI98680. (May 1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent J.D., Stukel T.A., Kresel J., Klein R.Z. Normal values for random urinary calcium to creatinine ratios in infancy. J. Pediatr. 1993;123(3):393–397. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81738-x. (Sep) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer J.A. Re: loss-of-function mutations of CYP24A1, the vitamin D 24-hydroxylase gene, cause long-standing hypercalciuric nephrolithiasis and nephrocalcinosis. Eur. Urol. 2015;68(1):164–165. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers J., Hynes A.M., Srivastava S., Dowen F., Quinton R., Datta H.K., Sayer J.A. Successful treatment of hypercalcaemia associated with a CYP24A1 mutation with fluconazole. Clin. Kidney J. 2015;8(4):453–455. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfv028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlingmann K.P., Kaufmann M., Weber S., Irwin A., Goos C., John U., Misselwitz J., Klaus G., Kuwertz-Bröking E., Fehrenbach H., Wingen A.M., Güran T., Hoenderop J.G., Bindels R.J., Prosser D.E., Jones G., Konrad M. Mutations in CYP24A1 and idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365(5):410–421. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlingmann K.P., Ruminska J., Kaufmann M., Dursun I., Patti M., Kranz B., Pronicka E., Ciara E., Akcay T., Bulus D., Cornelissen E.A., Gawlik A., Sikora P., Patzer L., Galiano M., Boyadzhiev V., Dumic M., Vivante A., Kleta R., Dekel B., Levtchenko E., Bindels R.J., Rust S., Forster I.C., Hernando N., Jones G., Wagner C.A., Konrad M. Autosomal-recessive mutations in SLC34A1 encoding sodium-phosphate cotransporter 2A cause idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016;27(2):604–614. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014101025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A.D., Hsiao E.C., O'Donnell B., Salmeen K., Nussbaum R., Krebs M., Baumgartner-Parzer S., Kaufmann M., Jones G., Bikle D.D., Wang Y., Mathew A.S., Shoback D., Block-Kurbisch I. Maternal hypercalcemia due to failure of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin-D3 catabolism in a patient with CYP24A1 mutations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;100(8):2832–2836. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalova S., Cerna L., Bayer M., Kutilek S., Konrad M., Schlingmann K.P. Intravenous pamidronate in the treatment of severe idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia. Iran. J. Kidney Dis. 2013;7(2):160–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebben P.J., Milliner D.S., Horst R.L., Harris P.C., Singh R.J., Wu Y., Foreman J.W., Chelminski P.R., Kumar R. Hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, and elevated calcitriol concentrations with autosomal dominant transmission due to CYP24A1 mutations: effects of ketoconazole therapy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;97(3):E423–E427. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf P., Muller-Sacherer T., Baumgartner-Parzer S., Winhofer Y., Kroo J., Gessl A., Luger A., Krebs M. A case of "late-onset" idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia secondary to mutations in the CYP24A1 gene. Endocr. Pract. 2014;20(5):e91–e95. doi: 10.4158/EP13479.CR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods G.N., Saitman A., Gao H., Clarke N.J., Fitzgerald R.L., Chi N.W. A young woman with recurrent gestational hypercalcemia and acute pancreatitis due to CYP24A1 deficiency. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2016;31(10):1841–1844. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2859. (Oct) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]