Abstract

Objective

Describe research methods used in priority-setting exercises for musculoskeletal conditions and synthesise the priorities identified.

Design

Scoping review.

Setting and population

Studies that elicited the research priorities of patients/consumers, clinicians, researchers, policy-makers and/or funders for any musculoskeletal condition were included.

Methods and analysis

We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE from inception to November 2017 and the James Lind Alliance top 10 priorities, Cochrane Priority Setting Methods Group, and Cochrane Musculoskeletal and Back Groups review priority lists. The reported methods and research topics/questions identified were extracted, and a descriptive synthesis conducted.

Results

Forty-nine articles fulfilled our inclusion criteria. Methodologies and stakeholders varied widely (26 included a mix of clinicians, consumers and others, 16 included only clinicians, 6 included only consumers or patients and in 1 participants were unclear). Only two (4%) reported any explicit inclusion criteria for priorities. We identified 294 broad research priorities from 37 articles and 246 specific research questions from 17 articles, although only four (24%) of the latter listed questions in an actionable format. Research priorities for osteoarthritis were identified most often (n=7), followed by rheumatoid arthritis (n=4), osteoporosis (n=4) and back pain (n=4). Nearly half of both broad and specific research priorities were focused on treatment interventions (n=116 and 111, respectively), while few were economic (n=8, 2.7% broad and n=1, 0.4% specific), implementation (n=6, 2% broad and n=4, 1.6% specific) or health services and systems research (n=15, 5.1% broad and n=9, 3.7% specific) priorities.

Conclusions

While many research priority-setting studies in the musculoskeletal field have been performed, methodological limitations and lack of actionable research questions limit their usefulness. Future studies should ensure they conform to good priority-setting practice to ensure that the generated priorities are of maximum value.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42017059250.

Keywords: musculoskeletal disorders, rheumatology, scoping review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Independent, duplicate screening and extraction were conducted to minimise bias.

It is possible that some priority-setting exercises were not identified despite the use of a broad search strategy.

All priority-setting exercises were conducted in high-income countries, and thus, their results may not be generalisable to middle-income or low-income settings.

Background

Conditions, such as low back and neck pain, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout and ‘other’ musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions, have the fourth greatest impact on global health according to the Global Burden of Disease study.1 In Australia, MSK conditions account for over 10% of the total disease burden and make up almost a quarter (23%) of the total non-fatal burden.2 They are among the top 30 most frequently managed chronic conditions in Australia,3 and contribute notably to total health expenditure.4 In 2012, the total cost of arthritis and other MSK conditions in Australia was an estimated $5.5 billion, including both direct (treatment), and indirect (loss of productivity), costs.4

A review of MSK trial funding by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) between 2009 and 2013 identified that funding for this area was disproportionately low relative to its burden despite it being an acknowledged National Health Priority Area.5 It is therefore imperative that the limited funding directed to MSK health focus on the most important research priorities in the field to ensure the highest health return on investment.6

There are many ways of approaching priority setting including using Delphi methods (iterative consultations with stakeholders), trend analysis and modelling (to predict future burdens), scenario discussion, matrix approaches (using quantifiable data to consider the potential effect), and discrete choice methods (to evaluate trade-offs).7 8 The James Lind Alliance, for example, advocates a mixture of literature reviews, Delphi surveys and workshops that involve a range of stakeholders in identifying and ranking the top 10 priorities in order of importance.9

The Australia and New Zealand Musculoskeletal (ANZMUSC) Clinical Trials Network was recently established to optimise MSK health through high quality, collaborative clinical trials research and to build research capacity in this field.10 To ensure that we focus on the most important evidence and evidence-practice gaps that are of most relevance to patients, clinicians, consumers and policy-makers, we aim to establish our own list of research priorities. To inform this work, we performed a scoping review of previous priority-setting projects for MSK conditions. Our aims were both to describe the methods used to establish research priorities, as well as to synthesise the priorities that have been identified previously. In particular, we were interested in whether or not any previous priority-setting projects had used a transparent method to order their set of priorities and whether any identified priorities would be of use in our own priority-setting process.

Methods

Selection criteria

We included articles that reported on research prioritisation for any type of MSK condition. We defined MSK conditions as any form of arthritis (eg, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, gout), autoimmune rheumatic conditions (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus, SLE), regional specific or non-specific MSK conditions (eg, low back pain), fractures and osteoporosis. Articles were included if they directly identified research priorities or research gaps from stakeholders including clinicians, consumers and researchers, irrespective of whether they were highly refined research questions or broad/more general research topics. There was no limitation on age or setting. Priority setting for pain in general or major trauma was excluded. We also excluded editorials, commentaries, narrative reviews, priorities considered as part of clinical guidelines and priorities relating solely to outcome measurement, for example, outcome measures in rheumatology initiatives.

Search strategy

We searched Ovid MEDLINE and EMBASE since inception to 20 November 2017 unrestricted by language. The specific search terms are listed in online supplementary appendix 1. We also searched the reference lists of included articles to identify additional relevant studies, the websites of the James Lind Alliance (http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/), their priority-setting partnerships (http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/priority-setting-partnerships/) and their priorities list (http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/top-10-priorities/), the website of the Cochrane Priority Setting Methods Group (http://methods.cochrane.org/prioritysetting/resources), and the Cochrane Musculoskeletal and Cochrane Back groups priority lists for reviews.

bmjopen-2018-023962supp001.pdf (271.6KB, pdf)

Data abstraction and synthesis

The title and abstracts of identified articles were independently screened by random and different pairs of reviewers across the author group. The full texts of potentially eligible articles were obtained and also screened by random and different pairs of reviewers across the author group. We attempted to contact the authors of any articles that we could not obtain by other means. Discordant decisions were resolved by discussion or a third reviewer (RVJ or RB), if necessary.

For all included articles, two independent reviewers (AMB or SC and another reviewer across the author group) extracted relevant data to a standard data extraction form (online supplementary appendix 2). It included the following information: setting, participants (clinicians, consumers, researchers, policy-makers, industry representatives, etc), MSK condition(s), method(s) used to develop research priorities), criteria for priorities (if used), method of priority weighting (if used), funding and the priority topics identified. Differences in data extraction between reviewers were resolved by discussion or by a third reviewer if necessary (RB or RVJ).

bmjopen-2018-023962supp002.pdf (387.1KB, pdf)

Priorities that were only research topics (eg, ‘rehabilitation strategies’),11 were classified as broad priorities, while those that were specific research questions (eg, ‘what is the relevance and use of red flags in the management of MSK conditions?’),12 were classified as specific priorities. Two independent reviewers (AMB and either RB, CM or JL) further categorised all identified research priorities into themes. These empirically derived themes were then condensed in number to 13 themes: epidemiology and burden; aetiology and risk factors; screening, diagnosis and assessment; natural history, prognosis and outcome; prevention; treatment (including prediction of response and mechanisms/rationale for treatment); outcome measurement; economic evaluation; implementation; health services and systems; research capacity building; research methods; and patient/consumer perspectives (focus on the impact or well-being of the patient). They were also mapped to a specific condition if relevant. Discrepancies in categorisation were discussed and resolved by consensus. No formal assessment of the quality of the prioritisation exercises was performed.

Patient involvement

One consumer representative but no patients were involved in the development, conduct or analysis of this review.

Results

Search results

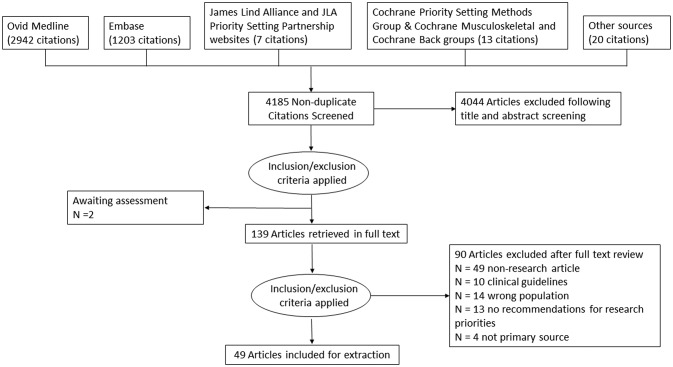

We retrieved 4185 non-duplicate citations from our searches including 20 from other sources (figure 1). Of these, 4044 citations were excluded after screening titles and abstracts. Of 141 potentially eligible articles, two could not be located in full text (despite attempts to contact the first author) and therefore could not be screened (‘awaiting assessment’),13 14 leaving 139 for full-text review. Of these, 90 were excluded. Reasons for exclusion are summarised in figure 1 and detailed in online supplementary appendix 3). These included non-research articles, guidelines and articles that did not specify a list of research priorities.

Figure 1.

Article extraction flow chart.

bmjopen-2018-023962supp003.pdf (418.8KB, pdf)

Included studies

Conditions

Forty-nine articles fulfilled our inclusion criteria.11 12 15–61 Most articles (n=29, 59%) were published in the last 10 years.11 12 16–19 22–25 27–35 37–39 44 46 49–52 54 Twenty-two (45%) made priority recommendations for MSK conditions broadly or recommendations across a range of conditions.12 15–30 55–58 61 For single conditions, research priorities for osteoarthritis were identified most often (n=7),11 31–36 followed by rheumatoid arthritis (n=4),38 41–43 osteoporosis (n=4)37 39 40 44 and back pain (n=4).45 46 48 53 Two studies identified priorities for orthopaedic surgery52 60 and foot and ankle conditions not otherwise classified by a disease.47 59 Single studies identified priorities for gout,50 systemic sclerosis,51 surgery for common shoulder conditions49 and juvenile-onset SLE.54

Location and approach

The characteristics of the priority-setting processes in the included articles are summarised in table 1. One-third (n=14, 29%) included stakeholders from multiple continents while 33 (67%) were country specific. Almost half (n=23, 47%) used a combination of methods, including literature review, surveys and/or workshops.16 17 27 31–34 36 38–41 44 49 51–58 61 A combination of survey(s) and workshop(s) was the most common multimodal approach, while surveys or focus groups were common in unimodal approaches. Of the 11 (22%), priority-setting exercises that were informed by a systematic review,16 27 31–33 36 40 51 52 54–58 61 only one explicitly reported their search terms.36

Table 1.

Methods, specific characteristics of the priority-setting approach, participants and funding of the included studies (n=49)

| N (%) | |

| Method/s used to identify priorities | |

| Combination of methods* | 23 (46.9) |

| Consensus (only)† | 22 (44.9) |

| Survey (only) | 4 (8.2) |

| Specific characteristics of the priority-setting approach | |

| Predefined explicit criteria for what constitutes a priority | 2 (4.1) |

| Priorities limited to a specific area | 15 (30.6) |

| Priorities pregenerated (not produced by stakeholders) | 5 (10.2) |

| Methods for refining research priorities reported | 32 (65.3) |

| Ranking of some or all priorities | 34 (69.4) |

| Weighting by an explicit method | 2 (4.1) |

| Update or reassessment of an earlier priority-setting activity | 5 (10.2) |

| Explicit strategy to implement priorities reported | 11 (22.4) |

| Participants | |

| Participants from ≥2 continents | 14 (28.6) |

| UK | 12 (24.5) |

| USA and/or Canada | 19 (38.8) |

| Europe | 2 (4.1) |

| Australia | 2 (4.1) |

| Total no of participants reported (range 9–1396) | 35 (71.4) |

| Method for identifying participants reported | 23 (46.9) |

| Level of stakeholder involvement clear | 28 (57.1) |

| Clinicians (only) | 42 (85.7)/(16 (32.7)) |

| Consumers or patients (only) | 19 (38.8)/(6 (12.2)) |

| Range of stakeholders‡ | 26 (53.1) |

| Participants unclear | 1 (2) |

| Funding | |

| Not explicitly reported | 18 (36.7) |

| Multiple funders | 7 (14.3) |

| Professional association§ | 8 (16.3) |

| Hospital/institute | 3 (6.1) |

| Government | 8 (16.3) |

| Consumer organisation | 2 (4.1) |

| Industry | 1 (2) |

| Not funded | 2 (4.1) |

*Studies included multiple methods (eg, survey and workshop).

†Consensus methods could have included workshops, group discussion, expert panels, nominal group techniques, focus groups, Delphi studies.

‡Other stakeholders included government, industry, researchers, educators, managers, administrators and funding agencies.

§Professional associations included orthopaedic nurses and trauma, rheumatology, physiotherapy and chiropractic groups.

Priority criteria, synthesis, implementation and evaluation

Only 2 priority-setting exercises (4%) reported explicit criteria for what could be considered a priority,15 23 15 (31%) limited priorities to specific research areas (eg, non-pharmacological interventions)17 19 20 24 26 30 33 34 38 40 41 43 44 52 54 and 5 (10%) asked participants to rank preidentified priorities (although allowed them to suggest additional items).27 32 36 47 58 The majority of articles broadly described how identified priorities were refined (n=32, 65%),12 15–17 19 20 22–28 31 32 34–36 39 40 43–46 48 49 52–54 57 59 60 12 of which (24%) included a thematic analysis.12 16 20 23–25 28 35 36 39 44 54 While most priority-setting exercises resulted in a ranked list of priorities, only two articles described priority weighting (by giving participants’ top three preferences across all categories double weighting,44 or by allocating 100 points across their choices).59 Only four groups or organisations updated or repeated their priority-setting exercise (The National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses,26 60 The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy14 23 The International Forum for Primary Care Research on Low Back Pain)46 53 and the Research Council of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society.47 59 Another group assessed the progress related to chiropractic research priorities but did not generate new priorities.62 63 Eleven studies (22%) outlined a strategy for implementing their priorities,22 24 31 44 49 52 55–58 61 (most of which were published since 2011)22 24 31 44 49 and one group (5%) reported that they had commenced a clinical trial to investigate one of the priorities identified.43

Participants

Sixteen priority-setting studies only included clinicians,11 15 26 33 42 43 46 48 52 55–61 six only included consumers or patients18 22 27 44 50 54 and in one the participants involved were unclear.37 Almost two-thirds of the studies (n=26, 53%) included a mix of clinicians, consumers and/or a range of others (eg, from industry, government and research backgrounds).12 16 17 19–21 23–25 28–32 34–36 38–41 45 47 49 51 53 Of the priority-setting exercises published since 2011 (n=23), less than half (n=11, 48%) include a range of stakeholders.11 17 22 27 33 37 39 44 46 50 51 54 Two studies compared research priorities of different stakeholders.19 36 The majority of studies clearly explained the level of stakeholder involvement (n=28, 57%), and of those that included clinicians, 33% (n=14) selected specific individuals to panels or workshops.15 19 28–33 35 36 38 39 45 48

Funding

Most studies reported their funding source (n=31, 63%). Only two reported that no funding was received,46 50 while the remainder received funding from either professional associations,12 17 24 26 42 43 52 60 hospitals/institutes,28 32 36 government,20 35 55–58 61 consumer groups22 40 or multiple sources.11 27 39 41 44 45 49

Themes of identified research priorities

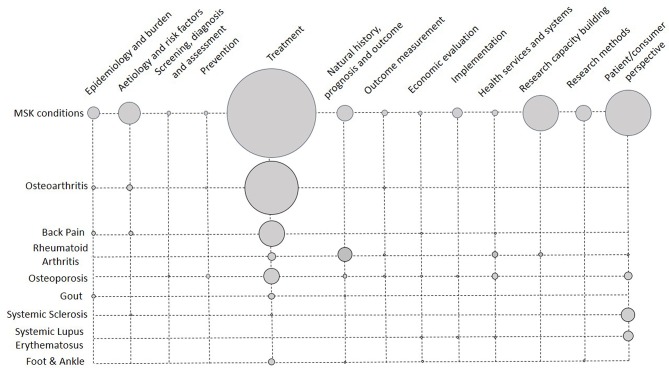

Thirty-seven articles identified 294 research priorities that were presented as broad topics or statements such as ‘biological perspective’ or ‘economic evaluations’ to indicate a general research area that was considered a priority (table 2 and online supplementary appendix 4). The median (IQR) number of broad topics identified per article was 7 (4–10). The most common theme they fell under was treatment (n=116, 39%), followed by patient/consumer perspectives (n=41, 14%). Few of these broad topics identified as research priorities were for economic evaluations (n=8, 3%),17 19 37 45 47 54 57 58 or screening, diagnosis and assessment (n=3, 1%).18 29 44 Thirteen of these broad topics were for specific foot conditions that required research and were not included in the thematic analysis because they could have been included in all themes.47 59

Table 2.

Summary of broad (n=37 articles, 294 priorities) and specific (n=17 articles, 246 priorities) research priorities

| Category | Broad topics | Specific questions | ||||

| N (%) | No of articles | No of conditions | N (%) | No of articles | No of conditions | |

| Epidemiology and burden | 12 (4.1) | 9 | 5 | 6 (2.4) | 2 | 2 |

| Aetiology and risk factors | 19 (6.5) | 13 | 6 | 18 (7.3) | 5 | 4 |

| Screening, diagnosis and assessment | 3 (1.0) | 3 | 2 | 14 (5.7) | 5 | 3 |

| Prevention | 5 (1.7) | 5 | 3 | 4 (1.6) | 4 | 4 |

| Treatment | 116 (39.5) | 25 | 8 | 111 (45.1) | 16 | 8 |

| Natural history, prognosis and outcome | 22 (7.5) | 11 | 5 | 18 (7.3) | 8 | 7 |

| Outcome measurement | 9 (3.1) | 8 | 4 | 18 (7.3) | 5 | 3 |

| Economic evaluation | 8 (2.7) | 8 | 5 | 1 (0.4) | 1 | 1 |

| Implementation | 6 (2.0) | 5 | 2 | 4 (1.6) | 4 | 4 |

| Health services and systems | 15 (5.1) | 7 | 5 | 9 (3.7) | 4 | 3 |

| Research capacity building | 28 (9.5) | 9 | 2 | 6 (2.4) | 2 | 2 |

| Research methods | 11 (4.1) | 8 | 3 | 2 (0.8) | 2 | 1 |

| Patient/consumer perspective | 41 (13.9) | 13 | 5 | 21 (8.5) | 5 | 2 |

bmjopen-2018-023962supp004.pdf (594.3KB, pdf)

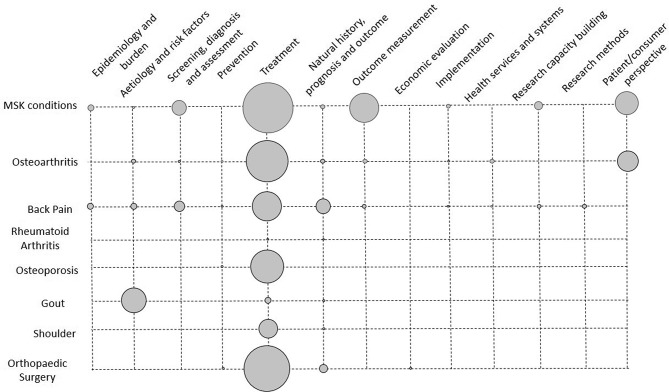

Seventeen (38%) articles identified 246 priorities in the form of specific research questions (table 2 and online supplementary appendix 5), with a median of 10 (IQR 5–17) priorities per article. Most of these specific research questions were for treatment (n=111, 45%) and only nine priorities (4%) from four priority-setting exercises were related to health services and systems research.32 35 46 57 Most specific research questions identified as priorities were not reported in an actionable form. Only three (18%) articles reported all31 49 or some32 priorities in the form of Patient Intervention Control Outcomes (PICO)-formatted questions, and one article listed specific Cochrane review topics.34

bmjopen-2018-023962supp005.pdf (563.9KB, pdf)

Figures 2 and 3 show the number of broad research topics and specific research questions identified as priorities for each condition. The majority of both broad research topics and specific research questions identified as priorities were focused on treatments (n=116, 39% and n=111, 45%, respectively), although no treatment priorities were identified for SLE.54 The majority of broad research topics listed as priorities (see figure 2) were from priority-setting exercises that considered MSK conditions broadly, or across several conditions (n=170, 58%), with ≥2 priority topics listed for each theme. Despite only being considered in three priority-setting exercises,22 37 39 the 24 broad research topics identified as priorities for osteoporosis were spread across nine themes. Only specific research questions were identified as priorities in priority-setting exercises for shoulder and orthopaedic surgery (see figure 3). Specific research questions from two back pain priority-setting exercises45 46 were identified as priorities across 11 research themes, while the one exercise for osteoporosis40 only identified specific questions as priorities across the themes of prevention and treatment.

Figure 2.

Matrix of broad research topics identified as priorities in musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions. Size of the circles indicates the number (N) of priorities.

Figure 3.

Matrix of specific research questions identified as priorities in musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions. Size of the circles indicates the number (N) of priorities.

Discussion

We identified 49 articles published up until November 2017 that reported on some form of research prioritisation in MSK conditions. These initiatives identified 294 priorities listed as broad research topics and 246 priorities listed as specific research questions. Most priorities concerned treatment of MSK conditions broadly or multiple conditions. Relatively few articles considered implementation or health services and systems research, and only three priority-setting exercises translated some or all their priorities into specific, actionable well-constructed research questions (eg, in PICO format).

There is no universally accepted gold standard for priority-setting exercises, however, critical aspects include clearly defining the context, use of a detailed structured approach to guide the process, explicit criteria for what constitutes a priority, inclusiveness of all stakeholders and ensuring their representativeness, being well informed, transparency and plans for both implementation and evaluation.64 65 The broad results of this study are similar to systematic reviews of priority-setting projects in other fields,66–69 in that no study clearly considered all the critical aspects necessary to make a priority-setting exercise of maximum benefit. Many of the priority-setting exercises identified in this review involved a range of stakeholders. Engagement of all relevant stakeholders is recognised as an essential component of priority-setting exercises, since research that is relevant to all parties is more likely to be adopted in practice.70 71 While nearly 50% of the priority-setting exercises in our review reported some level of consumer or patient engagement, similar to other systematic reviews,70 the manner and extent of engagement varied.

As noted in other fields,67 68 priority-setting exercises that only involved consumers, such as the one for SLE,54 tended to list broader priorities relating to quality of life and support, consistent with systematic review evidence in this area.72 In contrast, clinician-only priorities, such as those identified for orthopaedic surgery,52 were generally more specific and focused on diagnostic or treatment aspects. Most also generally lacked sufficient methodological detail to enable replication including an explicit description of what would be considered a priority. Finally, only a minority were informed by a literature review, which while not relevant for all situations, is important in verifying that priorities are truly based on uncertainties or need.9 While we did not note any improvement in priority-setting methods or stakeholder involvement in our review since publication of a checklist identifying the nine common themes of good priority-setting practice in 2010,65 this may require more time. By contrast, systematic reviews of priority setting in other fields have noted an increased breadth of stakeholder involvement over time.67 68 Such lack of detail severely limited the utility of the priorities identified as a starting point for ANZMUSC’s own priority setting, and highlighted the need to be inclusive and comprehensive in conducting and reporting our own priority-setting exercises.

Disease burden is often a major consideration in identifying research priorities,65 yet, the priorities that were identified in the 49 included articles do not reflect the relative burden of different MSK conditions. Back pain is the leading cause of disability globally,73 but only three priority-setting exercises focused on generating priorities specifically for back pain. Similarly, neck pain is currently the sixth leading cause of global disability,73 but it was not considered by any group. In contrast, osteoarthritis, which is currently the 12th leading cause of disability globally,73 was considered in eight articles. A similar discord between burden and research was noted in a scoping review which found that in Australia, more clinical trials were being funded and conducted for osteoarthritis than back and neck pain combined.5 The discord between burden of disease and condition-specific research prioritisation likely reflects a lack of recognition of disease burden and/or other drivers of priority setting.

It was also noteworthy that very few priority-setting exercises generated priorities related to economic evaluation, implementation and health services and systems, despite the ability for improvements in service delivery models to reduce the burden on the healthcare system and consequently improve patient care.74 A distinct lack of priorities in health services and economic research relative to treatment and prevention priorities was also noted in a review of research priorities for kidney disease.67 This may be the result of a lack of health service providers, funders and policy-makers involvement with priority-setting exercises.

It is difficult to assess the extent to which the priorities identified in these articles have informed current trials or research funding, or the extent to which they have been adopted into the health services field. Only a limited number of groups have reviewed their priority list, and none have performed a rigorous evaluation, therefore, the utility of these efforts is unknown. For example, while trials investigating self-management interventions and implementation trials were identified as research priorities by several groups, a scoping review looking at what types of MSK clinical trials had been funded by the Australian government from 2009 to 2013 found that most trials were focused on investigating the value of physical therapy and drug interventions.5

This systematic review has a number of strengths and limitations. The broad search strategy helped ensure that no conditions were excluded. Also independent screening, assessment and data extraction by two authors ensured that data were collected in a manner that minimised bias. Although we attempted to identify all relevant MSK condition priority-setting exercises, it is possible that some articles may have been missed, particularly those in the grey literature and in health policy documents. Further, the priority-setting exercises were all conducted in high-income countries and we did not identify any published priority-setting exercises specifically for low-income or middle-income countries. Therefore, the identified research priorities may or may not be transferable to these settings.

In summary, only 3 out of the 49 articles we reviewed identified specific research priorities in a well-constructed format using replicable methods, and most priorities focused on treatment. We recommend that future research priority-setting initiatives have a clear aim, use robust methods, include all relevant stakeholders and have a plan for implementation and evaluation. This will ensure greatest return on investment.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AMB: research idea and study design, data acquisition, data analysis/interpretation, first draft, manuscript drafting and/or revision. RVJ: research idea and study design, data acquisition, data analysis/interpretation, manuscript drafting and/or revision. SC: data acquisition, manuscript drafting and/or revision. AMB: data acquisition, manuscript drafting and/or revision. OC: data acquisition, manuscript drafting and/or revision. GD: data acquisition, manuscript drafting and/or revision. IAH: data acquisition, manuscript drafting and/or revision. CaH: data acquisition, manuscript drafting and/or revision. ClH: data acquisition, manuscript drafting and/or revision. SJK: data acquisition, manuscript drafting and/or revision. JL: data acquisition, data analysis/interpretation, manuscript drafting and/or revision. AL: data acquisition, manuscript drafting and/or revision. C-WCL: data acquisition, manuscript drafting and/or revision. CM: data acquisition, data analysis/interpretation, manuscript drafting and/or revision. DP: data acquisition, manuscript drafting and/or revision. BLR: data acquisition, manuscript drafting and/or revision. PS: data acquisition, manuscript drafting and/or revision. WJT: data acquisition, manuscript drafting and/or revision. SW: data acquisition, manuscript drafting and/or revision. RB: research idea and study design, data acquisition, data analysis/interpretation, manuscript drafting and/or revision.

Funding: This study was supported by an NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence grant for the Australia and New Zealand Musculoskeletal (ANZMUSC) Clinical Trials Network (APP1134856). CM is supported by an NHMRC Principal Research Fellowship, C-WCL is supported by an NHMRC career development fellowship, AMB is supported by an NHMRC TRIP Fellowship and RB is supported by an NHRMC Senior Principal Research Fellowship.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Kassebaum NJ, Arora M, Barber RM, et al. . Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. The Lancet 2016;388:1603–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31460-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The burden of musculoskeletal conditions in Australia: a detailed analysis of the Australian burden of disease study 2011. Canberra: AIHW, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Britt H, Miller G, Henderson J, et al. . General practice activity in Australia 2015–16. Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arthritis and Osteoporosis Victoria. Arthritis & Osteoporosis victoria. a problem worth solving: the rising cost of musculoskeletal conditions in Australia. Elsternwick: Arthritis and Osteoporosis Victoria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bourne AM, Whittle SL, Richards BL, et al. . The scope, funding and publication of musculoskeletal clinical trials performed in Australia. Med J Aust 2014;200:88–91. 10.5694/mja13.10907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tunis SR, Stryer DB, Clancy CM. Practical clinical trials: increasing the value of clinical research for decision making in clinical and health policy. JAMA 2003;290:1624–32. 10.1001/jama.290.12.1624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization. WHO and Special programme for research training in tropical diseases. priority setting methodologies in health research. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Montorzi G, de Haan S, IJsselmuiden C. Priority setting for research for health: a management process for countries: council on health research for development (COHRED). 2010.

- 9. The James Lind Alliance. The james lind alliance guidebook. 6 edn Offord, UK: James Lind Alliance, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buchbinder R, Maher C, Harris IA. Setting the research agenda for improving health care in musculoskeletal disorders. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2015;11:597–605. 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chu CR, Beynnon BD, Buckwalter JA, et al. . Closing the gap between bench and bedside research for early arthritis therapies (EARTH): report from the AOSSM/NIH U-13 Post-Joint Injury Osteoarthritis Conference II. Am J Sports Med 2011;39:1569–78. 10.1177/0363546511411654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rushton A, Moore A. International identification of research priorities for postgraduate theses in musculoskeletal physiotherapy using a modified Delphi technique. Man Ther 2010;15:142–8. 10.1016/j.math.2009.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bury T. Priorities for physiotherapy research 1997: results of a consultation exercise. London: The Chartered Society, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14. The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. The chartered society of physiotherapy. priorities for physiotherapy research in the UK: project report. London: The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15. American Physical Therapy Association. Clinical research agenda for physical therapy. Phys Ther 2000;80:499–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bergsten U, Andrey AM, Bottner L, et al. . Patient-initiated research in rheumatic diseases in Sweden--dignity, identity and quality of life in focus when patients set the research agenda. Musculoskeletal Care 2014;12:194–7. 10.1002/msc.1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Foster NE, Dziedzic KS, van der Windt DA, et al. . Research priorities for non-pharmacological therapies for common musculoskeletal problems: nationally and internationally agreed recommendations. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2009;10:3 10.1186/1471-2474-10-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kjeken I, Ziegler C, Skrolsvik J, et al. . How to develop patient-centered research: some perspectives based on surveys among people with rheumatic diseases in Scandinavia. Phys Ther 2010;90:450–60. 10.2522/ptj.20080381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murphy KJ, Kelekis DA, Rundback J, et al. . Development of a research agenda for skeletal intervention: proceedings of a multidisciplinary consensus panel. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2008;31:678–86. 10.1007/s00270-008-9305-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. National occupational research agenda for musculoskeletal disorders: research topics for the next decade, a report by the NORA Musculoskeletal Disorders Team. Cincinnati, Ohio: DHHS, PHS, CDC, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Palchik NS, Laing TJ, Connell KJ, et al. . Research priorities for arthritis professional education. Arthritis Rheum 1991;34:234–40. 10.1002/art.1780340218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parsons S, Thomson W, Cresswell K, et al. . What do young people with rheumatic disease believe to be important to research about their condition? A UK-wide study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2017;15:53 10.1186/s12969-017-0181-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rankin G, Rushton A, Olver P, et al. . Chartered society of physiotherapy’s identification of national research priorities for physiotherapy using a modified delphi technique. Physiotherapy 2012;98:260–72. 10.1016/j.physio.2012.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rubinstein SM, Bolton J, Webb AL, et al. . The first research agenda for the chiropractic profession in Europe. Chiropr Man Therap 2014;22:9 10.1186/2045-709X-22-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rushton AB, Fawkes CA, Carnes D, et al. . A modified Delphi consensus study to identify UK osteopathic profession research priorities. Man Ther 2014;19:445–52. 10.1016/j.math.2014.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Salmond SW. Orthopaedic nursing research priorities: a Delphi study. Orthop Nurs 1994;13:31–45. 10.1097/00006416-199403000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Strauss VY, Carter P, Ong BN, et al. . Public priorities for joint pain research: results from a general population survey. Rheumatology 2012;51:2075–82. 10.1093/rheumatology/kes179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Walton DM, Elliott JM, Lee J, et al. . Research priorities in the field of posttraumatic pain and disability: results of a transdisciplinary consensus-generating workshop. Pain Res Manag 2016;2016:1859434:1–8. 10.1155/2016/1859434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Weinrich M, Rosen BG. Musculoskeletal research conference summary report. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2007;86:S1–18. 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31802ba3b4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Winthrop KL, Strand V, van der Heijde DM, et al. . The unmet need in rheumatology: reports from the targeted therapies meeting 2016. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016;34:69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Crowe S, Regan S. Description of a process and workshop to set research priorities in hip and knee replacement for osteoarthritis. 2014.

- 32. Gierisch JM, Myers ER, Schmit KM, et al. . Prioritization of patient-centered comparative effectiveness research for osteoarthritis. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:836–41. 10.7326/M14-0318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Henrotin Y, Chevalier X, Herrero-Beaumont G, et al. . Physiological effects of oral glucosamine on joint health: current status and consensus on future research priorities. BMC Res Notes 2013;6:115 10.1186/1756-0500-6-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jaramillo A, Welch VA, Ueffing E, et al. . Prevention and self-management interventions are top priorities for osteoarthritis systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:503–10. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jinks C, Ong BN, O’Neill TJ. The Keele community knee pain forum: action research to engage with stakeholders about the prevention of knee pain and disability. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2009;10::85 10.1186/1471-2474-10-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tallon D, Chard J, Dieppe P. Relation between agendas of the research community and the research consumer. Lancet 2000;355:2037–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02351-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Adler RA, Bates DW, Dell RM, et al. . Systems-based approaches to osteoporosis and fracture care: policy and research recommendations from the workgroups. Osteoporos Int 2011;22:495–500. 10.1007/s00198-011-1708-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. American College of Rheumatology Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trial Investigators Ad Hoc Task Force. American college of rheumatology clinical trial priorities and design conference, July 22-23, 2010. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:2151–6. 10.1002/art.30402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Giangregorio LM, MacIntyre NJ, Heinonen A, et al. . Too Fit To Fracture: a consensus on future research priorities in osteoporosis and exercise. Osteoporos Int 2014;25:1465–72. 10.1007/s00198-014-2652-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Handoll HH, Madhok R. From evidence to best practice in the management of fractures of the distal radius in adults: working towards a research agenda. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2003;4:27 10.1186/1471-2474-4-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li LC, Bombardier C. Setting priorities in arthritis care: care III Conference. J Rheumatol 2006;33:1891–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. MacDermid JC, Fess EE, Bell-Krotoski J, et al. . A research agenda for hand therapy. J Hand Ther 2002;15:3–15. 10.1053/hanthe.2002.v15.0153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ota S, Cron RQ, Schanberg LE, et al. . Research priorities in pediatric rheumatology: The Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) consensus. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2008;6:5 10.1186/1546-0096-6-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Paskins Z, Jinks C, Mahmood W, et al. . Public priorities for osteoporosis and fracture research: results from a general population survey. Arch Osteoporos 2017;12:45 10.1007/s11657-017-0340-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Borkan JM, Cherkin DC. An agenda for primary care research on low back pain. Spine 1996;21:2880–4. 10.1097/00007632-199612150-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Costa LC, Koes BW, Pransky G, et al. . Primary care research priorities in low back pain: an update. Spine 2013;38:148–56. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318267a92f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Digiovanni C, Banerjee R, Villareal R. Foot and ankle research priority 2005: report from the research council of the American orthopaedic foot and ankle society. Foot Ankle Int 2006;27:133–4. 10.1177/107110070602700211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, et al. . Low back pain research priorities: a survey of primary care practitioners. BMC Fam Pract 2007;8:40 10.1186/1471-2296-8-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rangan A, Upadhaya S, Regan S, et al. . Research priorities for shoulder surgery: results of the 2015 James Lind Alliance patient and clinician priority setting partnership. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010412 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Singh JA. Research priorities in gout: the patient perspective. J Rheumatol 2014;41:615–6. 10.3899/jrheum.131258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thombs BD, van Lankveld W, Bassel M, et al. . Psychological health and well-being in systemic sclerosis: State of the science and consensus research agenda. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:1181–9. 10.1002/acr.20187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Willett KM, Gray B, Moran CG, et al. . Orthopaedic trauma research priority-setting exercise and development of a research network. Injury 2010;41:763–7. 10.1016/j.injury.2010.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Borkan JM, Koes B, Reis S, et al. . A report from the second international forum for primary care research on low back pain. Reexamining priorities. Spine 1998;23:1992–6. 10.1097/00007632-199809150-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tunnicliffe DJ, Singh-Grewal D, Craig JC, et al. . Healthcare and research priorities of adolescents and young adults with systemic lupus erythematosus: a mixed-methods study. J Rheumatol 2017;44:444–51. 10.3899/jrheum.160720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Adams AH, Gatterman M. The state of the art of research on chiropractic education. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1997;20:179–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brennan PC, Cramer GD, Kirstukas SJ, et al. . Basic science research in chiropractic: the state of the art and recommendations for a research agenda. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1997;20:150–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mootz RD, Coulter ID, Hansen DT. Health services research related to chiropractic: review and recommendations for research prioritization by the chiropractic profession. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1997;20:201–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nyiendo J, Haas M, Hondras MA. Outcomes research in chiropractic: the state of the art and recommendations for the chiropractic research agenda. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1997;20:185–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Saltzman CL, Domsic RT, Baumhauer JF, et al. . Foot and ankle research priority: report from the research council of the American orthopaedic foot and ankle society. Foot Ankle Int 1997;18:447–8. 10.1177/107110079701800714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sedlak C, Ross D, Arslanian C, et al. . Orthopaedic nursing research priorities: a replication and extension. Orthop Nurs 1998;17:121–8. 10.1016/S1361-3111(98)80083-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sawyer C, Haas M, Nelson C, et al. . Clinical research within the chiropractic profession: status, needs and recommendations. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1997;20:169–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Haas M, Bronfort G, Evans RL. Chiropractic clinical research: progress and recommendations. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2006;29:695–706. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mootz RD, Hansen DT, Breen A, et al. . Health services research related to chiropractic: review and recommendations for research prioritization by the chiropractic profession. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2006;29:707–25. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Cowan K, Oliver S. The james lind alliance guidebook. Oxford, UK: James Lind Alliance, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Viergever RF, Olifson S, Ghaffar A, et al. . A checklist for health research priority setting: nine common themes of good practice. Health Res Policy Syst 2010;8:36 10.1186/1478-4505-8-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Rylance J, Pai M, Lienhardt C, et al. . Priorities for tuberculosis research: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10:886–92. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70201-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tong A, Chando S, Crowe S, et al. . Research priority setting in kidney disease: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;65:674–83. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Tong A, Sautenet B, Chapman JR, et al. . Research priority setting in organ transplantation: a systematic review. Transpl Int 2017;30:327–43. 10.1111/tri.12924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Reveiz L, Elias V, Terry RF, et al. . Comparison of national health research priority-setting methods and characteristics in latin America and the caribbean, 2002-2012. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2013;34:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Stewart R, Oliver S. A systematic map of studies of patients' and clinicians' research priorities. London: James Lind Alliance, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Briggs AM, Bragge P, Slater H, et al. . Applying a Health Network approach to translate evidence-informed policy into practice: a review and case study on musculoskeletal health. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:394 10.1186/1472-6963-12-394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wluka A, Chou L, Briggs A, et al. . Consumers’ perceived needs of health information, health services and other non-medical services: a systematic scoping review. Melbourne: MOVE muscle, bone & joint health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, et al. . Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 2017;390:1211–59. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Institute of Medicine Committee on Health Research and the Privacy of Health Information. The Value, Importance, and Oversight of Health Research : Nass S, Livit L, Gostin L, Beyond the HIPAA privacy rule: enhancing privacy, improving health through research. Washington (DC: National Academies of Press, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023962supp001.pdf (271.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-023962supp002.pdf (387.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-023962supp003.pdf (418.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-023962supp004.pdf (594.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-023962supp005.pdf (563.9KB, pdf)